Summary

Background

Pre-procedural computed tomography (CT) imaging assessment of the aortic valvular complex (AVC) is essential for the success of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). However, pre-TAVR assessment is a time-intensive process, and the visual assessment of anatomical structures at the AVC shows interobserver variability. This study aimed to develop and validate a deep learning-based algorithm for pre-TAVR CT assessment and anatomical risk factor detection.

Methods

This retrospective, multicentre study used AVC CT scans to develop a deep learning-based, fully automated algorithm, which was then internally and externally validated. After loading CT scans into the algorithm, it automatically assessed the essential anatomical structure data required for TAVR planning. CT scans of 1252 TAVR candidates continuously enrolled from Fuwai Hospital were used to establish training and internal validation datasets, while CT scans of 100 patients with aortic valve disease across 19 Chinese hospitals served as an external validation dataset. The validation focused on segmentation performance, localisation and measurement accuracy of key anatomical structures, detection ability of specific anatomical risk factors, and improvement in assessment efficiency.

Findings

Relative to senior observers, our algorithm achieved significant consistent performance with remarkable accuracy, efficiency and ease in segmentation, localisation, and the assessment of the aortic annulus perimeter-derived diameter, and other basic planes, coronary ostia height, calcification volume, and aortic angle. The intraclass correlation coefficient values for the algorithm in the internal and external validation datasets were up to 0.998 (95% confidence interval 0.998–0.998), respectively. Furthermore, the algorithm demonstrated high alignment in detecting specific anatomical risk factors, with accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity up to 0.989 (95% CI 0.973–0.996), 0.979 (95% CI 0.936–0.995), 0.986 (95% CI 0.945–0.998), respectively.

Interpretation

Our algorithm efficiently performs pre-TAVR assessments by using AVC CT imaging with accuracy comparable to senior observers, potentially improving TAVR planning in clinical practice.

Funding

National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2008100), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2022-I2M-C&T-B-044).

Keywords: TAVR, TAVI, CT, AI, Deep learning

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed and medRxiv on 7 March 2023 for research articles containing the keywords “deep learning”, “artificial intelligence (AI)”, “automatic”, “transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)”, “transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)”, and “CT”, without any limitations on date and language. A few studies employed deep learning to locate the annular plane, or other individual anatomical structures. One of these representative studies utilised a cascading neural network to detect the location of the sinus of the tricuspid valve but did not measure the aortic annulus' delineation and lacked compatibility and validation for bicuspid aortic valves. Additionally, the absence of fine leaflet segmentation made further analysis of the aortic valve (e.g. measurements of leaflet length and thickness) extremely difficult. Another representative study used U-Net to segment and make preliminary measurements of the tricuspid aortic valve. However, such study did not utilise a large dataset and also lacked compatibility with bicuspid aortic valves. Moreover, the study relied on empirical post-processing steps, which may present generalisation issues when dealing with data from different sources. None of the studies we found was able to analyse various anatomical structure variations compatibly, evaluate multiple pre-TAVR parameters, or achieve fully automatic, one-stop analysis without human intervention.

Added value of this study

In this retrospective, multicentre study, we show that the algorithm can be used in pre-TAVR planning for accurate and automatic assessment of the anatomy of the AVC and anatomical risk factors detection by analysing CT images. The study continuously enrolled a total of 1352 cases, with 800 cases for model training, 452 cases for internal validation, and 100 cases for external validation. Firstly, we conducted an in-depth verification of the spatial coordinate positioning accuracy for specific anatomical structure key points. These key points are decisive factors in constructing elements such as the annular plane. Secondly, we verified the accuracy of geometric parameter measurements for various analysis targets focused on pre-TAVR CT assessment, and further evaluated the potential impact of valve leaflet anatomical variation and calcification on positioning and assessment. Thirdly, we also verified the ability to detect anatomical risks, which serve as indicators for potential risk events due to unique anatomical structures. Lastly, we also tested whether the algorithm can be integrated into existing clinical workflows and enable observers to accelerate the analysis process while maintaining the quality of the analysis.

Through literature retrieval, this study represents the largest retrospective multicentre study in terms of sample size in the field of AI-related fully automatic pre-TAVR CT imaging assessment to date. Meanwhile, it is also the study with the most comprehensive set of evaluation parameters, and the anatomical structures of the enrolled patients are most diverse.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study showed that our algorithm can precisely and efficiently perform pre-operative CT image assessment for TAVR in a fully automated manner.

After encapsulating this algorithm into a system and deploying it onto a cloud computing platform, it has the potential to serve as an innovative application based on AI and big data. Furthermore, it could provide significant clinical and research value.

Introduction

In transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), a fully assembled artificial aortic valve is inserted into the diseased aortic valve through a catheter, replacing the original aortic valve and ensuring functional substitution. TAVR indications in patients with symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (AS) now include those who are ineligible or high-risk surgical candidates and those at low risk for conventional surgical valve replacement.1 TAVR is the first-line treatment for aortic valve disease, with over 1.3 million TAVRs performed worldwide in the past 20 years.2 The aging population in China is increasing, and, recently, TAVR has rapidly and significantly developed.3 Concurrently, the Chinese population generally exhibits severe calcification, with a high prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve disease. These characteristics pose higher demands on preoperative analysis for TAVR procedures.4,5

As TAVR is an interventional procedure, full understanding and assessment of the anatomy of the aortic valvular complex (AVC) by computed tomography (CT) imaging is crucial for optimal sizing of transcatheter heart valves and identifying patients at increased anatomical risk for adverse events.2,6 CT is the gold standard tool for pre-TAVR imaging assessment based on currently guidelines, and is an essential step in patient selection, developing strategies and ensuring procedure outcomes.6

Qualified observers from imaging core laboratories must be proficient in imaging evaluation methods. Throughout evaluation, observers must perform several steps sequentially, including observing, manual tuning views, positioning, outlining, and measuring the AVC. Pre-TAVR assessment depends on the specific manual software-based workflow and the observers' experience, and is a lengthy process.

Inexperienced observers lack the three-dimensional understanding of anatomical structures, as well as precision and proficiency in manual operations. Additionally, even for experienced observers, manual pre-TAVR assessment is time-consuming and repetitive. These challenges can result in assessment errors that significantly impact prosthesis selection and development of TAVR strategies.6

Recently, to reduce the observers' workload in pre-TAVR assessment and improve analysis efficiency, semi-automatic or automatic software tools have emerged.7,8 However, considering the aortic root's complex anatomical structure and variance from pathological and physical changes, traditional computer vision algorithms require additional manual adjustments to ensure accuracy. Artificial intelligence (AI), especially deep learning (DL), has made substantial strides in image-recognition tasks, showing revolutionary potential in several medical fields.9, 10, 11, 12 Lately, research has been conducted applying DL to the field of aortic valve disease, automatically obtaining measurement values for aortic valve morphology. However, due to the complex anatomical structure of the aortic valve, some anatomical variants were excluded from these studies. This has resulted in a lack of system robustness, failing to meet the practical needs of clinical reality. To date, no previous approach has addressed these challenges (see Table 1 for the multiple major gaps in the literature).

Table 1.

Literature review.

| Authors | Samples | Methods | Results | Major gaps addressed in report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kocka, Bartova et al.13 | 128 series from single centre | Philips HeartNavigator | Difference of APD −1.1 mm (95% CI, −6.9 to 4.7) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not included. Assessment with single-centre data Limited assessment of anatomical parameters. (Only APD) |

| Hokken, Ooms et al.8 | 50 series | Philips IntelliSpace Portal | Agaston score difference −0.11 (95% CI −53.8 to 53.4) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not specified. Assessment on non-contrast data Limited assessment of anatomical parameters and spatial coordinate of landmark positions (Only Agatston score in non-contrast scan) |

| Foldyna, Jungert et al.14 | 30 series | Syngo. CT–Valve pilot | Difference of APD 0.42 mm (95% CI, −1.76 to 2.61) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not included. Not fully automatic. Limited number of patients/series |

| Evertz, Hub et al.15 | 50 series | 3Mensio, CVI42, Syngo.Via | ICC of VOC up to 0.997 (CI 0.995–0.998) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not specified. Not fully automatic. Limited assessment of anatomical parameters and spatial coordinate of landmarks and positions (only VOC) |

| Queiros, Dubois et al.16 | 104 series | shape-based segmentation strategy | Difference of APD −0.01 mm (95% CI, −1.56 to 1.54) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not mentioned. Limited assessment of anatomical parameters. (Only annulus) No detail in segmentation metric, neither demo presentation; |

| Zheng, John et al.10 | 192 CT volumes from 152 patients and two sites | Marginal Spacing Learning | spatial coordinate of landmark positions error of aortic hinges 2.41 ± 1.50 mm (mean ± SD) | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not mentioned. No subset analysis, nor robustness analysis. Limited assessment of anatomical parameters; (Only including aortic hinges, left/right COH, aortic commissures) |

| Aoyama, Zhao et al.11 | 258 CT volumes from 138 patients | 3D full resolution U-Net | ADC 0.70 ± 0.06 (mean ± SD) for valves | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not mentioned. Only segmentation of valves, excluding calcification and other anatomical targets No assessment of any anatomical landmarks and positions |

| Pak, Caballero et al.12 | Twenty CT volumes from 8 patients for training and validation, 15 CT volumes for test | Spatial transformer network | ADC 0.898 for aortic root, and, ADC 0.656 for leaflet | Assessment of bicuspid/bi-leaflet cases is not included. Only segmentation of aortic root and valves, excluding calcification and other anatomical targets No assessment of anatomical landmark and parameters No subset analysis, nor robustness analysis |

SD: standard deviation, APD: annulus perimeter-derived diameter, CI: confidence interval, VOC: volume of calcification, COH: coronary ostial height, ADC: average Dice coefficient.

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate a new, clinically relevant, fully automatic assessment algorithm based on DL for pre-TAVR CT assessment. The algorithm can accurately and quickly perform critical parameter measurements and evaluations of the aortic root anatomy required for TAVR without human intervention. Additionally, it is required to detect anatomical risk factors based on this evaluation. Importantly, it must demonstrate adaptability to a diverse range of aortic valve anatomical variations and complex pathologies, thereby exhibiting substantial robustness and generalisability. As most of the challenges in the automation or intelligent pre-tavr CT assessment have not been addressed simultaneously in previous works, we summarise in Table 1 the previous gaps being tackled in this report. The algorithm is code-named FORSSMANN after Dr. Werner Forssmann, who performed the first-in-man cardiac catheterisation, as a tribute to his pioneering work.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this retrospective, multicentre study, we trained, developed, and internally and externally validated FORSSMANN using consecutively enrolled CT images from 20 hospitals across China between May 2018 and November 2022 (Fig. 1). CT scans were collected from Fuwai Hospital and subsequently divided into training (230,486 images from 800 candidates) and internal validation (134,199 images from 452 candidates) datasets. We also collected CT scans from 19 other hospitals for the external validation dataset (28,858 images from 100 patients) without matching for demographic variables (i.e. age, sex, and education). When constructing the training set and internal/external validation datasets, we manually selected only one systolic phase image sequence from each participant for inclusion in the dataset. The enrolled patients had various aortic valve anatomical characteristics, including tricuspid aortic valve (TAV) and bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) (Sievers bicuspid types 0, 1, and 2).13

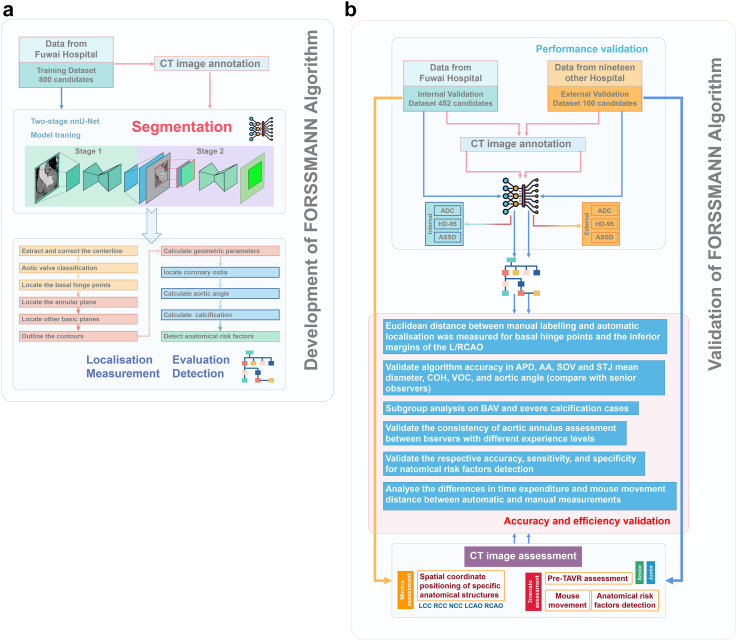

Fig. 1.

Algorithm development and validation flowchart. (a) Represents the algorithm development schematic, which includes DL model training and core function algorithm workflow (Number of training dataset = 800). (b) Represents the algorithm validation schematic, which includes algorithm performance verification, algorithm function verification, and algorithm efficiency verification (Number of internal/external validation datasets = 452/100).

All CT scans were stored in the DICOM format. An electrocardiogram-synchronised CT angiography scan covering at least the aortic root and heart was used. Image quality was controlled to exclude series with resolutions below 512 × 512 pixels, pixel size larger than 1 × 1 mm2, slice thickness above 1 mm, and severe artefacts (Consult Appendix, p 2, for more details of data collection and pre-processing).

Considering the DL segmentation model as the basis of FORSSMANN, we performed high-precision annotation on CT images. We used the training dataset for DL model training and hyper-parameter tuning by five-fold cross-validation. The validation dataset was used to evaluate the algorithm's performance, accuracy, robustness, and generalisation capabilities. The ablation experiment was improved in the two-stage segmentation pipeline compared to an end-to-end segmentation model. Five observers with varied clinical experience (three junior and two senior) were invited to assess the images in the validation dataset. Using the senior observers' assessments as references, we compared the consistency of FORSSMANN with those of the junior observers.

For anatomical risk factor detection, two senior observers detected and labelled five TAVR anatomical risk factors. We analysed the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of FORSSMANN using manually labelled anatomical risk factors as the gold standard.

Moreover, we performed a specialised analysis of the execution efficiency for both manual and FORSSMANN evaluation methods.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital (NO. 2021-1477). As our analysis was based solely on pre-existing retrospective medical data, patient consent was waived.

CT image assessment

In this study, in order to validate the algorithm's accuracy, two senior observers (with over five years of clinical experience. Consult Appendix pp 7–8 for more details about the validation of the consistency of the senior observer's evaluation.) assessed the CT images of the validation dataset. Initially, to verify the spatial coordinate positioning of specific anatomical structures, the observers utilised Mimics software version 19 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) to annotate basal hinge points (BHPs) and the inferior margins of the left and right coronary artery ostia (LCAO and RCAO).14,15 Subsequently, the pre-TAVR assessment was conducted using 3mensio version 10 software (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, Netherlands), including the aortic annulus, sinus of Valsalva (SOV), sinus-tubular junction (STJ), ascending aorta (AA), coronary ostial height (COH), aortic angle, and volume of calcification (VOC) (850 Hounsfield unit [HU]). The assessments of both observers were cross-validated to ensure accuracy. Disagreements were settled by an arbitrator with 15 years of cardiovascular clinical experience. Furthermore, to assess differences in interobserver consistency, three junior observers (less than three years of clinical experience) used the 3mensio software to conduct pre-TAVR assessments on the validation dataset. Meanwhile, to accurately evaluate the manual workload of the assessment process, we utilised Mousotron software (Blacksun Software, Turnhout, Belgium) to track mouse movement (Consult Appendix, pp 3–6, for more details).

CT image annotation

The CT images were labelled with Mimics. Six trained technicians completed the annotation process for all datasets according to a standardised annotation protocol; the results were subjected to quality control by two experienced physicians (Appendix, pp 9–11, for more details). Upon disagreements, an arbitrator made the final decision.

Anatomical risk factors detection

Anatomical risk factors are clear morphological abnormalities that physicians agree may increase the occurrence of adverse events during TAVR. These factors were identified via extensive pre-operative assessments combined with real procedure situations. This study validated the inter-rater agreement for the detection of five anatomical risk factors.2,6

The first was a horizontal aorta, defined as an aortic angle ≥48°.16 Moreover, an aortic angle >70° represents a significant risk of adverse events. The threshold was set at 70°.17

The second was an ascending aortic dilatation, defined as a diameter above 40 mm. Aneurysmal dilatation is considered when the ascending aortic diameter reaches or exceeds 1.5 times the expected normal diameter (>50 mm). The threshold was set at 50 mm.18

The third was severe calcification. A VOC in the AVC area above 600 mm³ significantly increases the probability of moderate or severe paravalvular leak and annulus rupture during TAVR.19 Severe calcification was defined as a VOC above 600 mm³.20,21

The fourth was exceptional SOV size. An overly large or narrow aortic sinus is associated with some adverse events.22 An aortic sinus diameter below 28 mm is considered too narrow, whereas a diameter above 45 mm is considered too large.15,23 These values were used as thresholds for classifying exceptional SOV size.

The fifth was low COH. Coronary artery occlusion is a severe intraoperative complication of TAVR, and a low COH may lead to coronary artery occlusion. When the COH is under 10 mm, special attention should be paid to the possibility of serious adverse events. The threshold value was set at 10 mm.2,6

Algorithm development

The FORSSMANN algorithm aims to evaluate the majority of anatomical structures shown in Fig. 2a. This evaluation process consisted of two steps. The first step was the automatic segmentation of the AVC based on DL, and the second step was the automatic location measurement evaluation based on the segmentation results (Fig. 1a). These two steps were completed automatically and continuously, without the need for manual intervention.

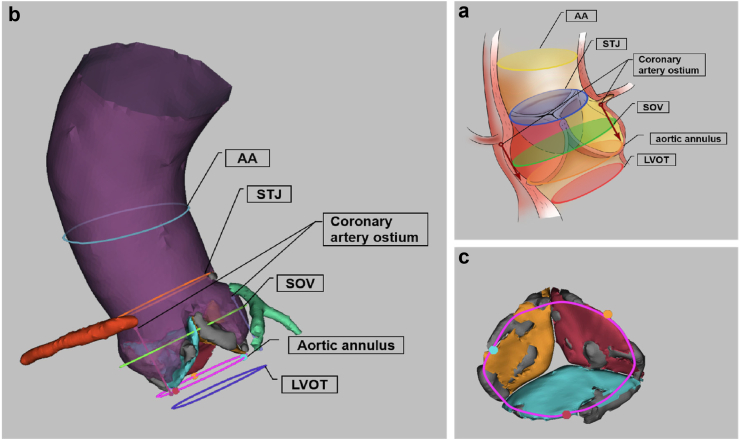

Fig. 2.

FORSSMANN assessment result and 3D reconstruction. (a) By taking the TAV as an example, the anatomical structure of the AVC region and the basic planes that need to be located and measured. The aortic angle was determined from the annular plane. The AA plane was located at the widest part of the AA. The STJ plane was located at the narrowest position where the aortic sinus transitions to the AA. The SOV plane was identified as the plane with the largest cross-sectional area of the lumen, based on the centreline between the annulus and STJ. In addition, the plane 4 mm below the annular plane vertically is the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) plane required for pre-operative evaluation of TAVR. The accuracy of LVOT positioning directly depends on the annular plane; therefore, this study did not conduct separate verification for the LVOT plane. (b) The algorithm completes the 3D reconstruction of the AVC model after automatic segmentation, localisation, and measurement. In the 3D reconstructed model, the aorta is shown in purple, the right coronary artery in red, the left coronary artery in green, the non-coronary cusp in orange, the right coronary cusp in blue, the left coronary cusp in pink, and calcified lesions in grey. Other completed localisation and measurement planes are shown in the figure. (c) This figure presents a partial schematic diagram of the aortic valve and calcified lesions from Figure A (observed from the left ventricular perspective). Orange represents the non-coronary cusp, blue represents the right coronary cusp, pink represents the left coronary cusp, and grey represents calcified lesions.

Segmentation model training

To segment the AVC structure, we deployed a nnU-Net-based two-stage coarse-to-fine DL network (Fig. 2b and c).24 The network included two segmentation networks: the coarse object and the fine object. In the first stage, the network segmented relatively obvious structures, including the aorta, left ventricle, left and right coronary arteries, calcification, and the aortic valve in which all leaflets were integrated. The integrated aortic valve was used as input for the second stage's model and produced two outputs: a binary output indicating the number of leaflets of the aortic valve and a fine segmentation output consisting of five-leaflet segmentation channels. Two channels specifically corresponded to the bi-leaflet structure (BAV without raphe), and the other three to the tri-leaflet structure (TAV or BAV with raphe) following the Hasan bicuspid aortic valve classification criteria.25 We utilised the same data augmentation strategy for training the two stages, which included random rotation and isotropic scaling (Appendix pp, 12–13).

Anatomical structure positioning and measurement

After completing the automatic segmentation of the AVC, the algorithm proceeded to the automatic positioning and evaluation stage. During this step, the algorithm conducted a series of fully automatic analysis processes such as centreline extraction, anatomical structure location and measurement based on the segmentation results. The specific steps were as follows:

The first step was to extract the centreline from the aorta to the left ventricle using the skeletonise algorithm,26 and then smooth the centreline using the following formulae:

represents the number of points on the centreline, and ‘i’ refers to the i-th point on the centreline.

According to the centreline, the original image was subjected to double oblique multiplanar reconstruction (DOMR).2 For each centre point, two direction vectors were extracted. The two direction vectors were perpendicular to the tangent vector of the centreline and the length of the direction vectors was normalised. In order to balance calculation accuracy and efficiency, we normalised the length of the direction vectors to 0.5 mm. Then, we rotated the direction vectors to ensure that the direction vectors of adjacent centre points were approximately the same and the trend of change was smooth. After this, we performed DOMR based on all direction vectors and centre points to get 2D image slices perpendicular to the centreline and subsequently stacked them into a 3D image.

The second step was positioning and measurement. Based on our understanding of the expert consensuses,2,6 we used algorithms to implement the positioning of the following key planes and anatomical structures: annular plane and BHPs. The positions of the annular plane and the BHPs are directly related. The variations in leaflet anatomical structure can lead to different numbers of BHPs, thus necessitating different methods for annular localisation. FORSSMANN implemented the automatic determination of the number of BHPs by recognizing the number of leaflets in the two-stage nnU-Net used in the automatic segmentation process. Based on the previously determined number of BHPs, we initiated the corresponding annular plane positioning process. For tri-leaflet structures, the annular plane was positioned tangent to all three BHPs (Fig. 3a). For bi-leaflet structures, the annular plane was selected with the smallest cross-sectional area by rotating the double oblique plane while keeping it tangent to both the BHPs (Fig. 3b). The annular plane and the segmented masks were processed using morphological methods to produce an outline, which was then smoothed to obtain the aortic annulus. Subsequently, parameters such as perimeter, area, and min/max diameters were calculated using analytic geometry methods.

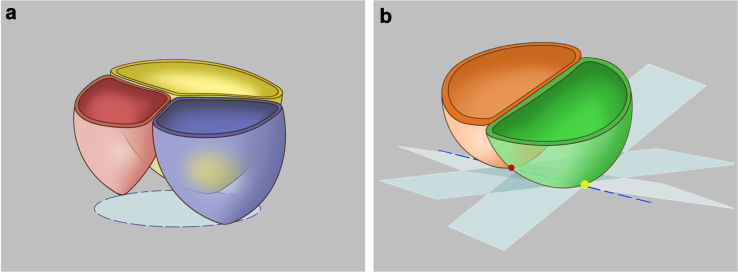

Fig. 3.

Schematic illustration of methods for positioning the annular plane in different anatomical classifications of the aortic valve. (a) For tri-leaflet structures (TAV, Type 1 BAV, Type 2 BAV), the annular plane is located at the plane determined by all three of the most basal attachment points of the aortic valve cusps. (b) For bi-leaflet structures (Type 0 BAV), the annular plane was positioned tangent to both the basal hinge points to achieve the smallest cross-sectional lumen.

Starting from the annular plane and following the centreline with a step length of 0.25 mm, perpendicular planes were continuously constructed. The numerical area of all perpendicular planes tangential to the segmented aortic mask was smoothed using the moving average method. We chose a reference plane that was 1 cm above the annular plane. The plane with the smallest area above this reference plane was designated as the STJ plane. Between the annular plane and the STJ plane, the plane with the largest area was selected as the SOV plane. Starting from the annular plane and moving along the centreline in the direction of the AA to 4 cm, this plane was designated as the AA plane. The methods for obtaining the contour lines corresponding to the above anatomical structures and the geometric parameter measurement methods were the same as those for the aortic annulus. Additionally, the method for measuring the diameters of the SOV depended on the number of BHPs, with the min/max diameters measured in the case of two BHPs, and three diameters based on morphological features measured in the case of three BHPs.

Based on the segmentation results of the aorta and the left/right coronary arteries, the intersecting areas between the coronary artery ostia and the aorta, which are LCAO and RCAO respectively, were obtained through morphological operations. Within these two regions, the points with the shortest distance to the annular plane were the inferior margins of LCAO/RCAO, and the corresponding distances were the left/right COH.

Additionally, the angle between the annular plane and the horizontal plane was calculated, which was referred to as the aortic angle. The total volume of the voxels in the calcification segmentation results with intensity higher than 850 HU was defined as the VOC.

Statistics

After calculating the sample size and comparing it with the sample sizes in previous studies, in pursuit of richer data diversity and more convincing statistical results, we determined that the internal validation dataset should consist of 452 cases, with an external validation dataset of 100 cases. We completed the following aspects of validation work on both internal and external validation datasets. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad 9.5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA), Python (version 3.8), and SPSS Statistics 29 (IBM, Armonk, USA).

We used the average Dice coefficient (ADC) to assess the overall performance of the segmentation model. To validate more refined segmentation targets such as calcified lesions and individually segmented leaflets, we further used the Hausdorff distance-95% (HD-95) and average symmetric surface distance (ASSD) to measure the geometric similarity between the ground truth and predicted results.

We used the Euclidean distance to validate the consistency of the spatial coordinates of specific anatomical positions automatically located by the algorithm and manually located by experienced observers. The specific anatomical positions referred specifically to the BHPs and the inferior margins of the LCAO and RCAO. We employed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Bland–Altman (BA) method to assess the consistency of measurements, such as aortic annulus perimeter-derived diameter (APD), mean diameter (encompassing AA, SOV, and STJ), COH, VOC, and aortic angle. We then performed subgroup analysis on BAV and severe calcification cases, which may significantly affect aortic annulus measurements, to validate FORSSMANN robustness. Additionally, we validated the consistency of aortic annulus assessment between observers with different experience levels and the FORSSMANN.

We validated the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of FORSSMANN in detecting five anatomical risk factors by referencing the assessment results of senior observers. Furthermore, we used t-tests to analyse the differences in time expenditure and mouse movement distance between automatic and manual measurements.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

The training, internal, and external validation datasets essentially spanned a variety of characteristics of patients with TAVR indications. These included patients with AS and aortic regurgitation (AR) from a disease perspective, patients with TAV and various types of BAV from a morphological perspective, and patients with various complex anatomical features (Table 2). With respect to demographic variables, the internal validation dataset had a mean age of about 74 years, slightly skewed towards male (57.5%). The external validation dataset had a mean age of approximately 73.8 years, predominantly male (54.0%).

Table 2.

Datasets characteristics.

| Training dataset | Internal validation dataset | External validation dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 800 | 452 | 100 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 73.5 (6.4) | 74.0 (7.8) | 73.8 (6.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 383 (47.9%) | 192 (42.5%) | 46 (46.0%) |

| Male | 417 (52.1%) | 260 (57.5%) | 54 (54.0%) |

| Aortic valve disease | |||

| AS | 722 (90.3%) | 421 (93.1%) | 86 (86.0%) |

| AR | 78 (9.7%) | 31 (6.9%) | 14 (14.0%) |

| Aortic valve classification | |||

| TAV | 514 (64.2%) | 265 (58.6%) | 61 (61.0%) |

| Type 0 BAV | 123 (15.4%) | 86 (19.0%) | 19 (19.0%) |

| Type 1 BAV | 155 (19.4%) | 98 (21.7%) | 18 (18.0%) |

| Type 2 BAV | 8 (1.0%) | 3 (0.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| VOC at 850 HU, mm³ | |||

| VOC ≤ 300 | – | 193 (42.7%) | 38 (38.0%) |

| 300 < VOC ≤600 | – | 119 (26.3%) | 26 (26.0%) |

| 600 < VOC ≤1200 | – | 105 (23.2%) | 25 (25.0%) |

| 1200 < VOC | – | 35 (7.8%) | 11 (11.0%) |

| Aortic annulus perimeter-derived diameter (D), mm | |||

| D ≤ 19 | – | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 19 < D ≤ 29 | – | 414 (91.6%) | 96 (96.0%) |

| 29 < D | – | 36 (8.0%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| AA mean diameter, mm | |||

| AA ≤ 40 | – | 259 (57.3%) | 68 (68.0%) |

| 40 < AA ≤ 50 | – | 162 (35.8%) | 29 (29.0%) |

| 50 < AA | – | 31 (6.9%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| SOV mean diameter, mm | |||

| SOV ≤ 28 | – | 52 (11.5%) | 11 (11.0%) |

| 28 < SOV ≤ 45 | – | 392 (86.7%) | 86 (86.0%) |

| 45 < SOV | – | 8 (1.8%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| Aortic angle (A), ° | |||

| A ≤ 48 | – | 211 (46.7%) | 43 (43.0%) |

| 48 < A ≤ 70 | – | 220 (48.7%) | 52 (52.0%) |

| 70 < A | – | 21 (4.6%) | 5 (5.0%) |

Baseline information on age and gender for all datasets were obtained from the DICOM tags recorded in the CT images. Other data were collected via through the evaluation of CT images by senior observers.

SD, standard deviation; AS, aortic valve stenosis; AR, aortic regurgitation; TAV, tricuspid aortic valve; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; VOC, volume of calcification; AA, ascending aorta; SOV, sinus of Valsalva.

Algorithm segmentation performance validation

In the first stage of model segmentation, the model demonstrated strong performance in segmenting obvious volume targets. The model achieved a satisfactory level of consistency with annotated results in the internal validation dataset: AA (ADC 0.985, 95% CI 0.985–0.985) and left ventricle (0.973, 0.972–0.974). Smaller volume targets also showed good consistency: left coronary artery (0.900, 0.864–0.907), right coronary artery (0.857, 0.843–0.871), calcification (0.837, 0.821–0.854), and integrated valve (0.791, 0.773–0.810). As an important segmentation target for downstream analysis, we assessed the ASSD and HD-95 of calcification. The ASSD for calcification was 0.238 mm (95% CI 0.172–0.305) and the HD-95 was 0.714 mm (0.609–0.819). Similar results were obtained in the external validation dataset (Appendix p 14).

In the second stage of model segmentation, we further segmented calcifications (ADC 0.866, 95% CI 0.856–0.877). Furthermore, bi-leaflet and tri-leaflet valves were segmented in different branches. The results indicated that the performance of bi-leaflet valves was (0.894, 0.860–0.928), whereas the performance of tri-leaflet valves was (0.869, 0.863–0.874). ASSD and HD-95 were also assessed for valves. The ASSD for bi-leaflet valves was 0.269 mm (0.131–0.405) and the HD-95 was 0.832 mm (0.479–1.185). The ASSD for tri-leaflet valves was 0.233 mm (0.211–0.256) and the HD-95 was 0.625 mm (0.575–0.676). Similar validations were conducted on the external validation dataset, yielding comparable results (Appendix p 14).

Ablation experiments were introduced to validate the two-stage design. We compared the current approach with directly training a neural network without cropping. Although the two-stage network design slightly increased the computation, it significantly improved segmentation performance (Appendix p 15).

Algorithm accuracy validation

An accurate pre-TAVR CT assessment relies on the meticulous positioning of anatomical landmarks. In this study, the Euclidean distance between manual labelling and automatic localisation was measured for BHPs and the inferior margins of the LCAO and RCAO.

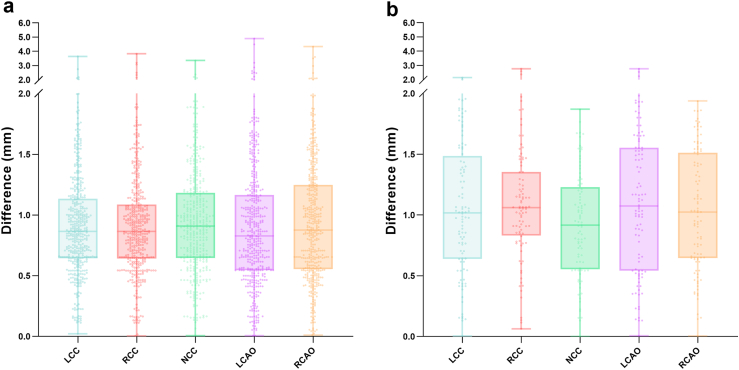

The validation shows that FORSSMANN has strong consistency with senior observers in terms of localisation accuracy for key anatomical structures (Table 3, Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of Euclidean distance of specific anatomical structures between FORSSMANN and senior observers.

| Internal dataset | External dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| LCC | 0.928 (0.432) | 1.017 (0.534) |

| RCC | 0.932 (0.455) | 1.098 (0.487) |

| NCC | 0.959 (0.441) | 0.947 (0.489) |

| LCAO | 0.928 (0.555) | 1.074 (0.597) |

| RCAO | 0.947 (0.527) | 1.042 (0.494) |

The LCC, RCC, and NCC represent the most basal attachment points of the three aortic valve cusps (sometimes referred to as the ‘basal hinge points'). The LCAO and RCAO represent the inferior margins of the coronary ostia. LCC, left coronary cusp; RCC, right coronary cusp; NCC, non-coronary cusp; LCAO, left coronary artery ostia; RCAO, right coronary artery ostia.

Fig. 4.

Statistical comparison of Euclidean distance for spatial localisation of specific anatomical structures by FORSSMANN and senior observers. (a) Statistical analysis results for the internal validation dataset (n = 452), (b) Statistical results for the external validation dataset (n = 100).

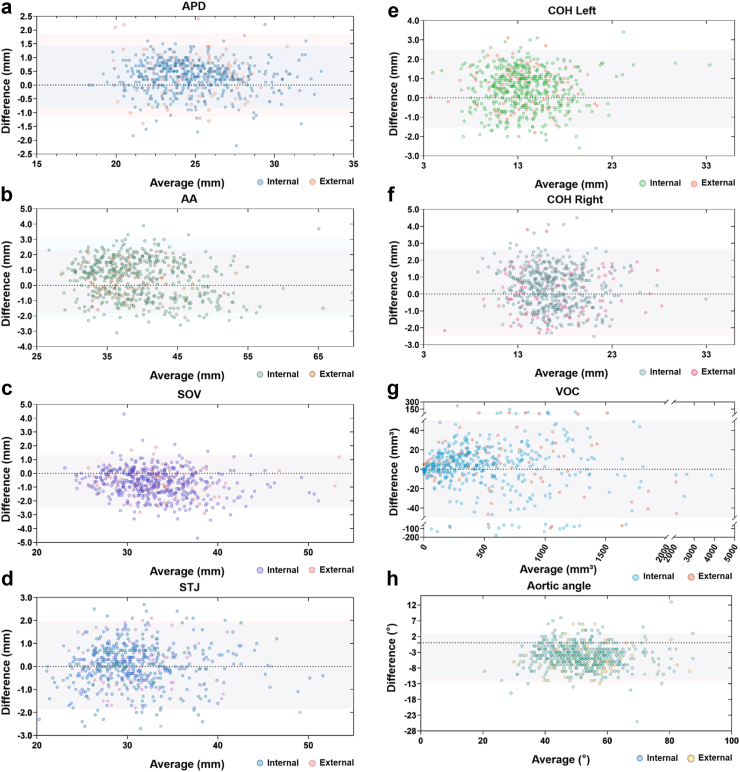

To validate the algorithm accuracy in evaluating the AVC, we compared the assessments of senior observers and FORSSMANN, including all key anatomical structures. In the internal validation dataset, the BA plots showed close mean differences between the AI and observers’ consensus of 0.977, 0.980, 0.976, 0.982, 0.957, 0.931, 0.998, and 0.935 with intraclass correlation coefficient values 0.971 (95% Confidence interval 0.943–0.983), 0.976 (0.966–0.982), 0.962 (0.877–0.982), 0.981 (0.978–0.984), 0.947 (0.923–0.962), 0.998 (0.998–0.998) and 0.866 (0.298–0.951) for the APD, the mean diameter (encompassing AA, SOV and STJ), COH, VOC, and aortic angle, respectively. The external validation dataset showed comparable results (Table 4, Fig. 5).

Table 4.

Pre-TAVR CT assessment data validation.

| Internal dataset |

External dataset |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (SD) | ICC | Distance | ICC | |

| APD, mm | 0.292 (0.575) | 0.985 | 0.382 (0.781) | 0.971 |

| AA, mm | 0.451 (1.327) | 0.988 | 0.259 (1.023) | 0.988 |

| SOV, mm | −0.722 (0.987) | 0.981 | −0.483 (0.963) | 0.986 |

| STJ, mm | 0.036 (0.937) | 0.982 | 0.048 (1.000) | 0.975 |

| Left COH, mm | 0.454 (1.025) | 0.973 | 0.542 (1.047) | 0.971 |

| Right COH, mm | 0.380 (1.190) | 0.960 | 0.024 (1.327) | 0.977 |

| VOC, mm3 | 3.421 (29.17) | 0.999 | 2.300 (29.42) | 0.999 |

| Aortic angle, ° | −4.225 (3.772) | 0.928 | −4.856 (4.027) | 0.910 |

The measurement error is shown as mean bias (SD) between FORSSMANN's and senior observers' measurement.

TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CT, computed tomography; SD, standard deviation; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; APD, annulus perimeter-derived diameter; AA, ascending aorta; SOV, sinus of Valsalva; STJ, sinus-tubular junction; COH, coronary ostial height; VOC, volume of calcification.

Fig. 5.

BA plotting comparing senior observers and the FORSSMANN algorithm. Comparison of (a) APD, (b) AA, (c) SOV, (d) STJ, (e) COH Left, (f) COH Right, (g) VOC, and (h) aoric angle with the y-axis representing the difference between senior observers and the FORSSMANN algorithm while the x-axis representing the average between these two values. The area covered by the blue shadow represents the confidence interval of the internal validation dataset (n = 452), while the area covered by the red shadow represents the confidence interval of the external validation dataset (n = 100).

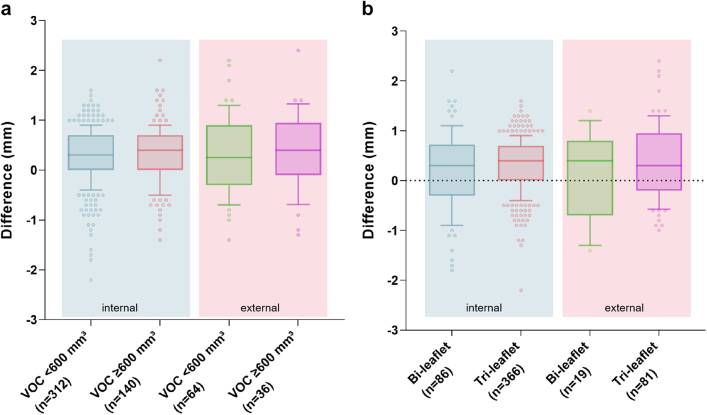

To evaluate the robustness of FORSSMANN under various conditions, such as severe calcification and different aortic valve anatomy, we conducted subgroup analyses on APD. Using a 600-mm³ VOC threshold, the mean error for low- and high-calcification patients in the internal validation dataset were 0.2875 (SD 0.5713) and 0.3164 (0.5793), respectively. In the external validation dataset, the average analysis errors were 0.3297 (0.7679) and 0.3917 (0.7799) for low- and high-calcification patients, respectively (Fig. 6a). Extensive calcification in the AVC may slightly affect the measurement accuracy of APD, but it remains within an acceptable range.

Fig. 6.

The impact of severe calcification and different aortic valve anatomy on FORSSMANN. (a) The impact of severe calcification on FORSSMANN in the internal and external validation datasets. (b) The impact of different valve leaflet types on FORSSMANN in the internal and external validation datasets (internal validation dataset n = 452) (external validation dataset n = 100).

We also verified whether FORSSMANN could maintain excellent accuracy under two different valve leaflet types. In the internal validation dataset, the mean APD errors for cases with bi- and tri-leaflet structures were 0.1837 (SD 0.7881) and 0.3230 (0.5078), respectively. In the external validation dataset, the mean errors for cases with bi- and tri-leaflet structures were 0.1211 (0.8817) and 0.4062 (0.7356), respectively (Fig. 6b). The measurement standard deviation for bi-leaflet structures was larger than that for tri-leaflet structures. This may be due to the natural instability of dual-hinge points structures. Based on this validation, we found that the FORSSMANN achieves high accuracy in both extreme calcification conditions and different leaflet types, demonstrating its robustness.

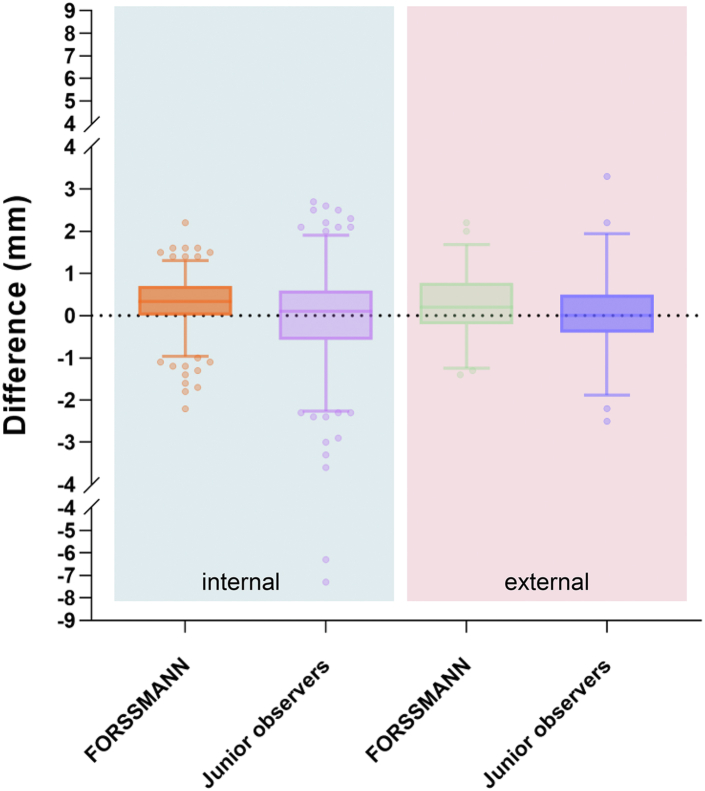

To verify the applicability of the FORSSMANN, we compared the algorithm's automatic assessments with the manual measurements from junior observers, using the APD measured by senior observers as the standard. The analysis errors for junior observers in the internal and external validation datasets were −0.02 (SD 1.043) and 0.06 (0.920), respectively (Fig. 7). Our algorithm exhibited a more stable analysis result than junior observers.

Fig. 7.

The measurement differences of the APD. Comparing the performance of the FORSSMANN algorithm and junior observers, with the senior observers serving as the reference standard (internal validation dataset n = 452) (external validation dataset n = 100).

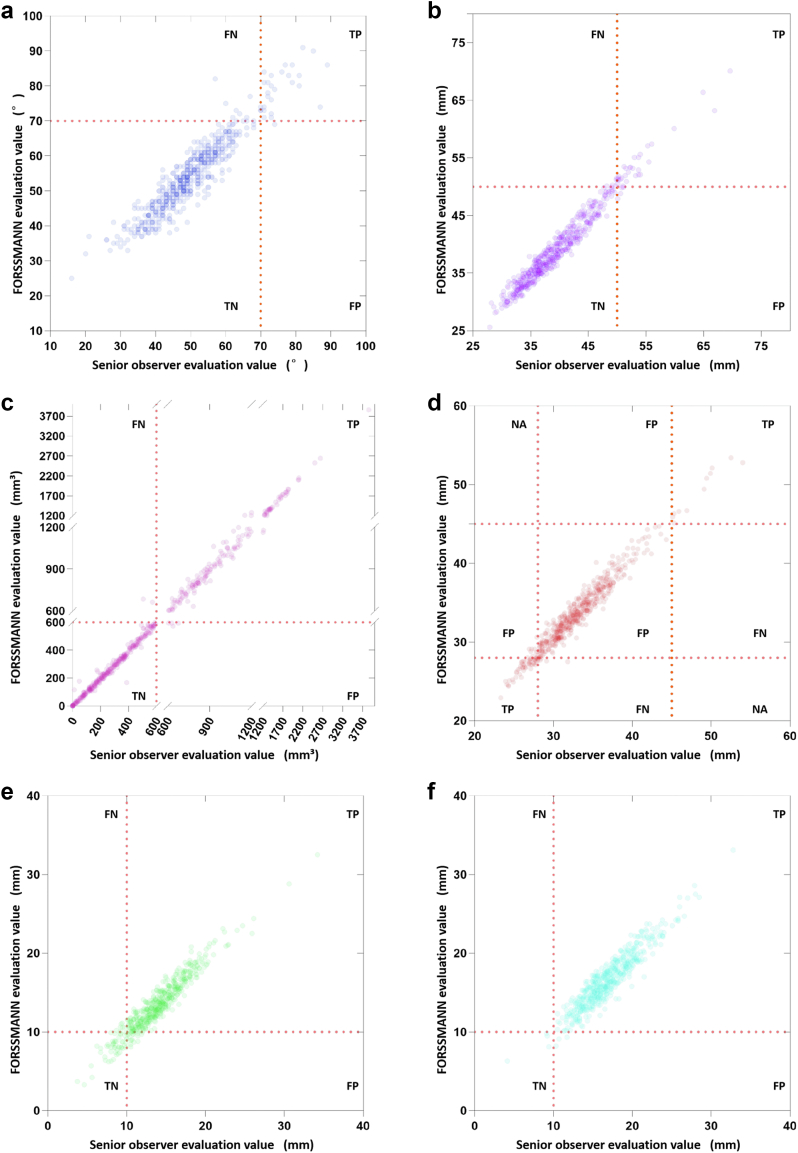

Anatomical risk factors detection validation

We validated FORSSMANN for detecting five anatomical risk factors on both internal and external validation datasets using the assessment results from experienced observers as the reference. Owing to the low occurrence rate of risk factors, we combined internal and external validation datasets to obtain more statistically meaningful results. The respective accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for risk detection of the horizontal aorta were 0.978 (95% CI 0.959–0.989), 0.954 (95% CI 0.751–0.998), and 0.700 (95% CI 0.504–0.846); AA dilation, 0.981 (95% CI 0.968–0.992), 0.871 (0.692–0.958), and 0.844 (0.665–0.941); severe calcification, 0.989 (0.973–0.996), 0.979 (0.936–0.995), and 0.986 (0.945–0.998); exceptional SOV size, 0.970 (0.949–0.983), 0.845 (0.720–0.922), and 0.907 (0.790–0.965); and low COH, 0.975 (0.933–0.973), 0.821 (0.692–0.907), and 0.780 (0.650–0.873) (Fig. 8). These demonstrate that FORSSMANN is similar to senior observers for detecting specific anatomical risks.

Fig. 8.

Risk factor detection results. The plotting figures of FORSSMANN evaluation value verse senior observers of (a) horizontal aorta, (b) AA dilation, (c) severe calcification, (d) exceptional SOV sizing, (e) low left COH and (f) low right COH (TP = True Positive, TN = True Negative, FP = False Positive, FN = False Negative, NA = Not Applicable). “Positive” refers to the detection of anatomical risk by senior observers, whereas “Negative” indicates no detection. “True” represents a match in detection results between FORSSMANN and senior observers, while “False” indicates a mismatch in detections (n = 552).

Efficiency improvement validation

To further investigate how FORSSMANN can improve pre-TAVR assessment efficiency, we compared the total time and mouse movement distance required for the manual and automatic approaches. The manual and automatic approaches consumed 19.50 ± 7.55 min and 0.86 ± 0.21 min per case, respectively, demonstrating a considerable reduction in time with FORSSMANN. Additionally, FORSSMANN significantly reduced in total mouse movement distance by 52.24 ± 16.92 m, suggesting that FORSSMANN can alleviate the workload and increase efficiency.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated an innovative, fully automated, DL-based algorithm customised for pre-TAVR assessment that can detect anatomical risk factors. Our specially optimised two-stage nnU-Net model can accurately segment the complex anatomical structure of the aortic root, classify aortic valves, and locate and measure the aortic annulus and other anatomical structures. It can also accurately quantify calcification and measure the aortic angle, among other parameters. To our knowledge, FORSSMANN is the first complete and fully automated DL-based algorithm for pre-TAVR assessment of the AVC using CT imaging.

We compared the consistency and effectiveness of the FORSSMANN algorithm across different levels of observer experience. The algorithm performed the required evaluations without any manual corrections and showed high consistency with the evaluations of experienced observers for critical indicators. Furthermore, the algorithm significantly outperformed junior observers and displayed robustness in assessing subgroups with bicuspid and severely calcified valves. Compared with that by senior observers, anatomical risk factors detection by FORSSMANN showed strong consistency. Moreover, the evaluation of mouse activity showed the superior efficiency of FORSSMANN.

FORSSMANN's core strengths lie in the accurate identification of key anatomical structures, coupled with high availability and usability (video 1). It provides significant improvements in assessment speed and effectively indicates anatomical risks. Therefore, FORSSMANN may help develop pre-TAVR imaging evaluation technology, shorten operators' learning curve, and promote TAVR procedures. Based on this, FORSSMANN has three significant advantages.

First, FORSSMANN is a fully automatic one-stop solution that closely matches the requirements of pre-TAVR assessment and was validated internally and externally. Pre-TAVR CT image assessment is a systematic evaluation process involving not only the annular plane but also the localisation and assessment of other critical anatomical structures. Recent studies used end-to-end DL methods to evaluate CT images of the aortic root, but with a limited number of assessment targets, no external validation, and non-representative patient populations.27, 28, 29 Previous studies focused on a single valve type, either BAV or TAV,30, 31, 32 whereas FORSSMANN is fully compatible with both types of patients, making it more versatile for diverse clinical applications.

The second advantage of FORSSMANN lies in its superior interpretability. DL plays a critical and fundamental role in the FORSSMANN algorithm, facilitating highly precise multi-target segmentation that was trained on a comprehensive, high-quality CT image annotation dataset comprising 800 cases. This is a significant improvement from previous studies with training datasets with less than 100 cases.8,28,29,31 Considering the segmentation and reconstruction results, the algorithm is designed to classify valve leaflets, localise the most basal attachment points of the aortic valve cusps, and identify the planes of various anatomical structures, completely following the human approach to such task.

The third advantage of FORSSMANN is its stronger robustness. The extreme cases in our study had calcification levels up to 3857 mm³, aortic angles up to 89°, AA dilation up to 69.6 mm, COH of 3.7 mm, SOV reaching a maximum of 54 mm, or a minimum of 23.3 mm. Cases with extremely complex anatomical structures were included, while these may not have been enrolled in previous research.8,27,28,33 In comparison to atlas-based segmentation, FORSSMANN exhibit greater robustness to compromised image quality, structural malformation, and severe pathological changes.33

Our study has some limitations. It is a retrospective study, and prospective validation would improve results. The study was conducted on the Chinese population, and the impact of morphological differences caused by racial diversity on the algorithm's generalisability requires validation. Future global multicentre randomised controlled trials can effectively address this issue. Cases with poor CT image quality and severe artefacts were excluded, and future optimisation should be undertaken to improve the algorithm's robustness. The study did not assess the occurrence of perioperative complications in patients undergoing TAVR. Future studies should collect data on actual prosthesis selection, intraoperative risk events, immediate postoperative functional indices, and postoperative follow-up to construct a model that can accurately predict and effectively validate perioperative complication risks and benefits based on anatomical structures. This study focused solely on the development and validation of an algorithm for pre-TAVR CT assessment, and lacks further research on TAVR prosthesis selection. Prosthesis selection is a core aspect of TAVR strategy. Future research should incorporate a thorough exploration of this aspect, combining individualized assessments of AVC anatomical structures, the design features of prostheses from different manufacturers, and finite element analysis techniques.This study is solely focused on the assessment of pre-TAVR CT imaging of the AVC. However, for a comprehensive pre-TAVR CT assessment, a CT assessment of the TAVR access route is also important. Future studies should conduct specialized research on the assessment of access route CT imaging, striving to address clinical concerns such as passability, tortuosity, calcification distribution, and prediction of peripheral vascular complications in the analysis of the access route. In this study, we used only single-modality data from CT imaging and did not utilise characteristics data from other modalities for model training. Future research that integrates multi-modal data may yield more results in predicting clinical benefits and long-term prognosis.

In conclusion, the proposed algorithm achieved accurate and generalisable performance for pre-TAVR AVC assessment and anatomical risk factors detection using CT. The algorithm has the potential to be encapsulated and deployed as a cloud service system. Considering its accuracy, generalisability, efficiency, and interpretability, the system could be used in clinical practice and scientific research to help develop and promote the TAVR procedure.

Contributors

MW, YW, and, GN designed the research. Investigators of China-DVD2 collected the data. MW, and, YW accessed and verified the underlying data. GN, ZZ, DF, YC, and, YZ performed CT image data annotation and completed the CT image evaluation. MW, and, YZ developed the DL-based algorithm and analysed the results. MW, GN, and, YW co-wrote the manuscript. YC, DF, and, YZ critically revised the manuscript, and, all authors discussed the results and provided feedback regarding the manuscript. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

Additional information related to this study is available on request to the corresponding author. The datasets used to train and validate the algorithm are not publicly available due to Chinese privacy and secrecy regulations. Due to the confidentiality requirements of the CHINA-DVD2 study, the algorithm code and DL model developed in this research cannot be released.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the support and assistance provided by the radiologist Xinshuang Ren from the Department of Radiology of Fuwai Hospital for this study. We thank National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2008100 to YW, MW, GN, YC, ZZ, DF, YZ and, the investigators of China-DVD2), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-C&T-B-044 to MW, and, YZ) for supporting this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104794.

Contributor Information

Yongjian Wu, Email: yongjianwu_nccd@163.com.

China-DVD2 Study Group (Standard Evaluation and Optimal Treatment for Elderly Patients with Valvular Heart Disease, National Key R&D Program of China, NCT05044338):

Yongjian Wu, Moyang Wang, Guangyuan Song, Haibo Zhang, Daxin Zhou, Fang Wang, Changfu Liu, Bo Yu, Kai Xu, Zongtao Yin, Hongliang Cong, Nan Jiang, Pengfei Zhang, Xiquan Zhang, Jian An, Zhengming Jiang, Ling Tao, Jian Yang, Junjie Zhang, Xianxian Zhao, Fanglin Lu, Xianbao Liu, Yanqing Wu, Jianfang Luo, Lianglong Chen, Zhenfei Fang, and Xiaoke Shang

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Patel K.V., Omar W., Gonzalez P.E., et al. Expansion of TAVR into low-risk patients and who to consider for SAVR. Cardiol Ther. 2020;9(2):377–394. doi: 10.1007/s40119-020-00198-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanke P., Weir-McCall J.R., Achenbach S., et al. Computed tomography imaging in the context of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)/transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR): an expert consensus document of the society of cardiovascular computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M., Song G., Chen M., et al. Twelve-month outcomes of the TaurusOne valve for transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis. EuroIntervention. 2022;17(13):1070–1076. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jilaihawi H., Wu Y., Yang Y., et al. Morphological characteristics of severe aortic stenosis in China: imaging corelab observations from the first Chinese transcatheter aortic valve trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85(Suppl 1):752–761. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu H., Liu Q., Cao K., et al. Distribution, characteristics, and management of older patients with valvular heart disease in China: China-DVD study. JACC Asia. 2022;2(3):354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacasi.2021.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francone M., Budde R.P.J., Bremerich J., et al. CT and MR imaging prior to transcatheter aortic valve implantation: standardisation of scanning protocols, measurements and reporting-a consensus document by the European Society of Cardiovascular Radiology (ESCR) Eur Radiol. 2020;30(5):2627–2650. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06357-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baessler B., Mauri V., Bunck A.C., et al. Software-automated multidetector computed tomography-based prosthesis-sizing in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: inter-vendor comparison and relation to patient outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hokken T.W., Ooms J.F., Kardys I., et al. Validation of a three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction tool for aortic valve calcium quantification. Struct Heart. 2023;7(2) doi: 10.1016/j.shj.2022.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribeiro J.M., Astudillo P., de Backer O., et al. Artificial intelligence and transcatheter interventions for structural heart disease: a glance at the (near) future. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2022;32(3):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y., John M., Liao R., et al., editors. Automatic aorta segmentation and valve landmark detection in C-arm CT: application to aortic valve Implantation. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoyama G., Zhao L., Zhao S., et al. Automatic aortic valve cusps segmentation from CT images based on the cascading multiple deep neural networks. J Imaging. 2022;8(1):11. doi: 10.3390/jimaging8010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pak D.H., Caballero A., Sun W., Duncan J.S. 2020 IEEE 17th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) 2020. Efficient aortic valve multilabel segmentation using a spatial transformer network. 3-7 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sievers H.H., Schmidtke C. A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(5):1226–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Writing Committee M., Otto C.M., Nishimura R.A., et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association JOINT Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):450–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vahanian A., Beyersdorf F., Praz F., et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscarelli M., Gallo F., Gallone G., et al. Aortic angle distribution and predictors of horizontal aorta in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Int J Cardiol. 2021;338:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Windecker S., Okuno T., Unbehaun A., Mack M., Kapadia S., Falk V. Which patients with aortic stenosis should be referred to surgery rather than transcatheter aortic valve implantation? Eur Heart J. 2022;43(29):2729–2750. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erbel R., Aboyans V., Boileau C., et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35(41):2873–2926. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawade T., Sheth T., Guzzetti E., Dweck M.R., Clavel M.A. Why and how to measure aortic valve calcification in patients with aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9):1835–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko E., Kang D.Y., Ahn J.M., et al. Association of aortic valvular complex calcification burden with procedural and long-term clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(11):1502–1510. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeab180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu G., Ali W.B., Wang M., et al. Anatomical morphology of the aortic valve in Chinese aortic stenosis patients and clinical results after downsize strategy of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Chin Med J. 2022;135(24):2968–2975. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomii D., Okuno T., Heg D., et al. Sinus of Valsalva dimension and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am Heart J. 2022;244:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saad M., Seoudy H., Frank D. Challenging anatomies for TAVR-bicuspid and beyond. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.654554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isensee F., Jaeger P.F., Kohl S.A.A., Petersen J., Maier-Hein K.H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods. 2021;18(2):203–211. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jilaihawi H., Chen M., Webb J., et al. A bicuspid aortic valve imaging classification for the TAVR era. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(10):1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang T.Y., Suen C.Y. A fast parallel algorithm for thinning digital patterns. Commun ACM. 1984;27(3):236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Astudillo P., Mortier P., Bosmans J., et al. Automatic detection of the aortic annular plane and coronary ostia from multidetector computed tomography. J Intervent Cardiol. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9843275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruger N., Meyer A., Tautz L., et al. Cascaded neural network-based CT image processing for aortic root analysis. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2022;17(3):507–519. doi: 10.1007/s11548-021-02554-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahoces P.G., Varela R., Carreira J.M. Deep learning method for aortic root detection. Comput Biol Med. 2021;135 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thalappillil R., Datta P., Datta S., et al. Artificial intelligence for the measurement of the aortic valve annulus. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(1):65–71. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theriault-Lauzier P., Alsosaimi H., Mousavi N., et al. Recursive multiresolution convolutional neural networks for 3D aortic valve annulus planimetry. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2020;15(4):577–588. doi: 10.1007/s11548-020-02131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X., He Y., Zhu Q., et al. Supra-annular structure assessment for self-expanding transcatheter heart valve size selection in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91(5):986–994. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao X., Boccalini S., Kitslaar P.H., et al. Quantification of aortic annulus in computed tomography angiography: validation of a fully automatic methodology. Eur J Radiol. 2017;93:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.