Abstract

Background

Alcohol consumption is related to the risk of developing different types of cancer. However, unlike other alcoholic beverages, moderate wine drinking has demonstrated a protective effect on the risk of developing several types of cancer.

Objective

To analyze the association between wine consumption and the risk of developing cancer.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE (through PubMed), Scopus, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis. Pooled relative risks (RRs) were calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird methods. I2 was used to evaluate inconsistency, the τ2 test was used to assess heterogeneity, and The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale were applied to evaluate the risk of bias. This study was previously registered in PROSPERO, with the registration number CRD42022315864.

Results

Seventy-three studies were included in the systematic review, and 26 were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled RR for the effect of wine consumption on the risk of gynecological cancers was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.08), that for colorectal cancer was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.03), and that for renal cancer was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.04). In general, the heterogeneity was substantial.

Conclusion

The study findings reveal no association between wine consumption and the risk of developing any type of cancer. Moreover, wine drinking demonstrated a protective trend regarding the risk of developing pancreatic, skin, lung, and brain cancer as well as cancer in general.

Systematic review registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022315864, identifier CRD42022315864 (PROSPERO).

Keywords: cancer, wine, adult people, alcohol consumption, systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Cancer is associated with some of the highest mortality and morbidity rates worldwide, surpassed only by cardiovascular diseases (1); an estimated 23.6 million cancer cases and 10 million cancer-related deaths occurred in 2019. Moreover, the incidence of cancer is expected to increase due to the decline in cancer screening and early diagnosis brought about by COVID-19 (2, 3). The main cancers causing disability-adjusted life years in both sexes affect the respiratory tract, such as the trachea, bronchus, and lung; the colon, rectum, stomach, breast, and liver are also common cancer sites, and breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in women (2, 4).

The main risk factors affecting the overall burden of cancer are smoking, alcohol consumption, and high body mass index (4), but non-modifiable risk factors such as genetics and age should not be overlooked considering that we will never be able to reduce their burden on cancer even if we try to address modifiable risk factors (5). Tobacco consumption appears to be the major risk factor for lung cancer (6), and studies have shown a concomitant effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on some cancers (7). Additionally, alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk for upper aerodigestive tract, colon, rectum, liver, head, neck, and breast cancer in women (8, 9), responsible for approximately 6 million new cancer cases and 3 million deaths in 2020 (10). However, the incidence of kidney cancers appears inversely associated with moderate alcohol consumption (11) (20 g/day (2 SBU) for men and 10 g/day (1 SBU) for women (12)), as reported by the World Health Organization.

Current knowledge regarding alcohol consumption and cancer remains controversial, specifically in relation to wine consumption. Some previous meta-analyses revealed no association between wine consumption and cancer but an increased risk of cancer with the consumption of other alcoholic beverages (13) and suggested that beer is associated with the highest risk for colorectal cancer (14). Regarding gynecological cancers, alcohol consumption may increase the incidence of both breast and ovarian cancer, although the role of wine consumption has not been clearly determined (15). Other risk factors for these cancers should be considered; age at menarche and BRCA gene carrier status for ovarian and breast cancer (16), and tubal ligation history and menopause age for ovarian cancer (17). Furthermore, unlike other alcoholic beverages, moderate wine consumption has shown a protective effect on the likelihood of developing different types of cancer, such as rectal (18, 19) and colorectal (19, 20) cancer. Other studies have found that wine consumption is not a risk factor for esophageal (21) or lung (22) cancer.

Due to the inconsistencies in the data regarding the relationship between wine consumption and cancer development and the increasing interest in the effects of wine on health, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to summarize the existing evidence on various cancers and analyze the effect of wine consumption independently from other alcoholic beverages. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic, and the aim was to analyze the association between wine consumption and general, upper digestive tract, colorectal, renal, pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, and gynecological cancer.

Methodology

Search strategy and selection of studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (23) and in accordance with the guidelines of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement (MOOSE) (24). This study was previously registered in PROSPERO, with the registration number CRD42022315864.

A systematic search of the MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases was conducted from their inception until 12 December 2022. The search strategy followed the PICO structure (population, intervention/exposure, comparison, outcome, and study design), using Boolean operators between the following terms: “adults,” “young adults,” “adult populations,” “adult subjects,” “older,” “elderly,” “elderly people,” “older people,” “alcohol,” “wine,” “alcohol consumption” “wine consumption,” “neoplasm,” “cancer,” “tumor,” “cancer risk,” “carcinogen*,” “mortalit*,” “cohort,” “cases and controls,” “longitudinal studies,” and “prospective studies” (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, references from previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses were reviewed.

Eligibility

The articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were longitudinal studies measuring the association between wine consumption and different types of cancer, including general, upper digestive tract, colorectal, renal, pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, and gynecological cancer. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) participants: general population; (ii) exposure: wine consumption as reported by the original studies; (iii) outcomes: different types of cancer; and (iv) study design: longitudinal studies (cohort and case–control studies). Conversely, studies were excluded when (i) they were review studies, ecological studies, editorials, or case reports; (ii) they were not written in English or Spanish; or (iii) they did not report wine consumption separately from other alcoholic beverages. No publication date restriction was applied.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following information was extracted from the included studies and synthesized in an ad hoc table (Table 1): (1) reference: first author and year of publication; (2) country; (3) study design; (4) participant characteristics: sample size, percentage of women, age, and type of population; (5) exposure follow-up in years (if reported); and (6) outcome: type of cancer. In addition, covariables used in the analyses of the included studies were summarized in an additional table since each study included different confounding variables.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the included studies.

| References | Country | Design of study | Characteristics of the participants | Follow up (years) | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, women (%) | Age* | Target population | Type of cancer | ||||

| Breast cancer | |||||||

| Harvey et al., 1986 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 1524 (100) Controls: 1896 (100) |

30–50 | General population | 5 | Breast cancer |

| Howe al., 1991 | Multicenter (Australia, Canada, Greece, Argentina and Italy) | Case–control | Cases: 1575 Controls: 1974 |

<30– >82 | General population | 3 | Breast cancer |

| Sneyd et al., 1991 | New Zealand | Case–control | Cases: 891 Controls:1864 |

25–54 | General population | 4 | Breast cancer |

| Friedenreich et al., 1993 | Canada, America | Case–control | N: 1701 Cases: 519 Controls: 1182 |

NR | General population | 5 | Breast cancer |

| Longnecker et al., 1995 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 6888 Controls: 9424 |

58.7 | General population | 3 | Breast cancer |

| Swanson et al., 1996 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 1668 (100) Controls:1501 (100) |

Cases: 40 (NR) Controls: 39 (NR) |

General population | 2 | Breast cancer |

| Zhang et al., 1999 | USA, America | Cohort | Framingham Study: 2873 Framingham Offspring Study: 5124 |

-Framingham Study: 68.4 (NR) -Framingham Offspring Study: 54.2 (NR) |

General population | -Framingham Study: 34.3 -Framingham Offspring Study: 19.3 |

Breast cancer |

| Rohan et al., 2000 | Canada, America | Cohort | 56,837 (100) | 40–59 | NBSS | 5 | Breast cancer |

| Horn-Ross et al., 2002 | USA, America | Cohort | 111,526 | 21–103 | California Teachers Study cohort | 2 | Breast cancer |

| Tjønneland et al., 2007 | Europe | Cohort | 368,010 (100) | 35–70 | EPIC cohort | 6.4 | Breast cancer |

| Li et al., 2009 | USA, America | Cohort | 70,033 | 40.6 (NR) | Multi-ethnic cohort. Members of a comprehensive pre-paid health care programme in the San Francisco Bay Area. | 16 | Breast cancer |

| Prostate cancer | |||||||

| Tavani et al., 1994 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 281 Controls: 599 |

Cases: 67 (NR) Controls: 63 (NR) |

General population | 7 | Prostate cancer |

| De Stefani et al., 1995 | Uruguay, America | Case–control | Cases: 156 Controls: 302 |

Cases: 40–89 Controls: 40–89 |

General population | 6 | Prostate cancer |

| Hayes et al., 1996 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 1292 Controls: 1767 |

40–79 | General population | 4 | Prostate cancer |

| Andersson et al., 1996 | Sweden, Europe | Case–control | Cases:256 Controls:252 |

Cases: 70.0 (6.1) Controls: 69.8 (6.2) |

General population | 3 | Prostate cancer |

| Jain et al., 1998 | Canada, America | Case–control | Cases: 617 Controls: 637 |

Cases: 69.8 (7.3) Controls: 69.9 (7.3) |

General population | 4 | Prostate cancer |

| Schuurman et al., 1999 | Netherlands, Europe | Cohort | 58,279 | 55–69 | NLCS | 6.3 | Prostate cancer |

| Breslow et al., 1999 | USA, America | Cohort | 3,775 | 25–74 | NHEFS Cohort | 9 | Prostate cancer |

| Putnam et al., 2000 | USA, America | Cohort | 1,577 | 68.1 (NR) | Cohort of Iowa men | 3 | Prostate cancer |

| Barba et al., 2004 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 88 Controls: 272 |

Cases: 69.3 (8.4) Controls: 70.0 (6.3) |

The PROMEN STUDY | 4 | Prostate cancer |

| Crispo et al., 2004 | Italy, Europe | Case–Control | 2,663 | Prostatic carcinoma: 66 (NR) Benign prostatic hyperplasia: 65 (NR) |

General population | 12 | -Prostate cancer -Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| Platz et al., 2004 | USA, America | Cohort | 47,843 | 54.7 (NR) | Health Professionals Follow-up Study |

12 | Prostate cancer |

| Chang et al., 2005 | Sweden, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 1130 Controls:1499 |

Cases: 66.4 (7.3) Controls: 67.3 (7.6) |

General population | 2 | Prostate cancer |

| Schoonen et al., 2005 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 753 Controls: 703 |

40–64 | Caucasian and African-American | 4 | Prostate cancer |

| Sutcliffe et al., 2007 | USA, America | Cohort | 45,433 | 53.8 (NR) | Health Professionals Follow-up Study | 4 | Prostate cancer |

| Renal cell cancer | |||||||

| Pelucchi et al., 2002 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 348 (32.18) Controls: 1048 (28.15) |

Cases: 60 (NR) Controls: 60 (NR) |

General population | 8 | Renal cell cancer |

| Rashidkhani et al., 2005 | Sweden, Europe | Cohort | 59,237 (100) | 40–76 | Swedish Mammography Cohort | 3 | Renal cell cancer |

| Greving et al., 2007 | Sweden, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 855 Control: 1204 |

Cases: 64.3 (NR) Controls: 64.4 (NR) |

General population | 3 | Renal cell cancer |

| Lew et al., 2011 | USA, America | Cohort | 492.187 (40.4) | 62.1 (NR) | NIH-AARP Diet and Health study | 9 | Renal cell cancer |

| Pancreatic cancer | |||||||

| Tavani et al., 1997 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 361 Control: 997 |

Cases: 60 (NR) Controls: 59 (NR) |

General population | 10 | Pancreatic cancer |

| Michaud et al., 2001 | USA, America | Cohort | HPFS: 10582 NHS:30083 |

HPFS: 54.5 (NR) NHS: 47.5 (NR) |

Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and Nurses’ Health Study | 4 | Pancreatic cancer |

| Heinen et al., 2009 | Netherlands, Europe | Cohort | 120,852 (50.52) | 62.1 (4.1) | Netherlands Cohort Study | 13.3 | Pancreatic cancer |

| Jiao et al., 2009 | USA, America | Cohort | 470,681 (40.5) | 62 (NR) | The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study | 7.3 | Pancreatic cancer |

| Gapstur et al., 2011 | USA, America | Cohort | 1,029,467 (56.02) | 33–111 | The Cancer Prevention Study II | 24 | Pancreatic cancer |

| Ovarian cancer | |||||||

| Gwinn et al., 1986 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 433 Controls: 2915 |

20–54 | General population | 2 | Ovarian cancer |

| La Vecchia et al., 1992 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 801 Controls: 2114 |

54 (NR) | General population | 7 | Ovarian cancer |

| Tavani et al., 2001 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 1031 Controls: 2411 |

Cases: 18–79 Controls: 17–79 |

General population | 7 | Ovarian cancer |

| Webb et al., 2003 | Australia, Oceania | Case–control | Cases: 696 (100) Controls: 786 (100) |

18–79 | General population | 3 | Ovarian cancer |

| Goodman et al., 2003 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 558 Controls: 607 |

54.8 (NR) | General population | 6 | Ovarian cancer (general): -Mucinous -Nonmucinous Invasive ovarian cancer: -Serous -Endometrioid -Mucinous |

| Modugno et al., 2003 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 761 -Nonmucinous cases: 649 -Mucinous cases: 112 Controls: 1352 |

20–69 | Study of Health and Reproduction Project | 5 | Ovarian cancer: -Nonmucinous -Mucinous |

| Schouten et al., 2004 | Netherlands, Europe | Cohort | 62,573 | 61.3 (4.2) | NLCS | 9.3 | Ovarian cancer |

| Peterson et al., 2006 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 762 Controls: 6271 |

Cases: 57.6 (NR) Controls: 59.8 (NR) |

General population | 3 | Ovarian cancer |

| Chang et al., 2007 | USA, America | Cohort | 90,371 (100) | 50 (NR) | The CTS cohort | 8.1 | Ovarian cancer |

| Cook et al., 2016 | Canada, America | Case–control | Cases: 1144 (100) Controls: 2513 (100) |

Cases: 59.6 (9.8) Controls: 57.1 (9.1) |

The OVAL-BC Study |

11 | Ovarian cancer |

| Aerodigestive tract cancers | |||||||

| Franceschi et al., 1990 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: -Oral cavity: 157 -Pharyns: 134 -Larynx: 162 -Esophagus: 288 Controls: 1272 |

<49– > 70 | General population | 3 | -Oral cavity -Pharynx -Larynx -Esophagus |

| Barra et al., 1990 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Oral cavity: 305 esophageal: 288 Controls: 1621 |

Oral cavity: 58 (NR) esophageal: 60 (NR) Controls: 57 (NR) |

General population | 5 | -Oral cavity -esophagus |

| Barra et al., 1991 | Italy, Europe | Case–control | Cases: 272 Control: 445 |

Cases: 60 (NR) Controls: 57 (NR) |

General population | 5 | -Oral cavity-pharynx |

| De Stefani et al., 1998 | Uruguay, America | Case–control | Cases: 471 Controls: 471 |

Cases 40–89 Controls 40–89 |

General population | 4 | -Oral cavity-pharynx |

| Grønbæk et al., 1998 | Denmark, Europe | Cohort | 28,180 (46.4) | 20–98 | The Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies | 13.5 | Upper digestive tract cancer |

| Huang et al., 2003 | Puerto Rico, America | Case–control | Cases: 286 Controls: 417 |

21–79 | General population | 3 | Oral cancer study |

| Aerodigestive tract cancers | |||||||

| Barstad et al., 2005 | Denmark, Europe | Cohort | -Copenhagen City Heart Study: 15.754 (53.8) -Copenhagen Male study: 3230 (0) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1897 cohort: 243 (58.4) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1914 cohort: 933 (49.6) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1936 cohort: 1107 (41.8) -MONICA I: 3774 (48.8) -MONICA II: 1413 (49.7) -MONICA III:2009 (50.5) |

-Copenhagen City Heart Study: 53 (NR) -Copenhagen Male study: 63 (NR) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1897 cohort: 80 (NR) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1914 cohort: 70 (NR) -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1936 cohort: 40 (NR) -MONICA I: 46 (NR) -MONICA II: 45 (NR) -MONICA III: 50 (NR) |

-Copenhagen City Heart Study -Copenhagen Male study -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1897 cohort -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1914 cohort -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1936 cohort -MONICA I -MONICA II -MONICA III |

-Copenhagen City Heart Study: 16.0 -Copenhagen Male study: 9.8 -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1897 cohort: 7.3 -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1914 cohort: 9.0 -Copenhagen Country Centre of Preventive Medicine 1936 cohort: 18.7 -MONICA I: 13.0 -MONICA II: 9.8 -MONICA III: 5.3 |

Gastric cancer risk |

| Pandeya et al., 2009 | Australia, Oceania | Case–control | -EAC: 365 (9.7) -EGJAG: 426 (13.2) -ESCC: 303 (43.1) -Controls: 1580 (34.2) |

-EAC: 63.6 (0.5) -EGJAG: 63.3 (0.5) -ESCC: 64.7 (0.5) -Controls: 60.5 (0.3) |

General population | 3 | -EAC -EGJAG -ESCC |

| Skin carcinoma | |||||||

| Fung et al., 2002 | USA, America | Cohort | NHS: 3060 HPFS: 3028 |

NHS: 30–55 HPFS: 40–75 |

Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and Nurses’ Health Study | NHS: 8 HPFS: 10 |

Skin carcinoma |

| Ansems et al., 2008 | Australia, Oceania | Cohort | 1,360 (57.6) | 49.7 (NR) | The Nambour Skin Cancer Study | 11 | -BCC -SCC |

| Lung cancer | |||||||

| Benedetti et al., 2006 | Canadá, America | Case–control | Study I Cases: 699 Controls: 507 Study II Men Cases: 640 Controls: 861 Study II Women Cases: 454 Controls: 607 |

Study I Cases: 59.0 (7.8) Controls: 59.7 (7.8) Study II Men Cases: 63.8 (8.0) Controls: 63.2 (7.7) Study II Women Cases: 60.9 (9.4) Controls: 60.7 (9.1) |

Study I: Men Study II: Men and women. |

10 | Lung cancer |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||||

| Potter et al., 1986 | Australia, Oceania | Case–control | COLON CANCER Cases: 220 (45) Controls: 438 (45) RECTUM CANCER Cases: 199 (37.7) Controls: 396 (37.4) |

30–74 | General population | 3 | -Colon cancer -Rectum cancer |

| Longnecker et al., 1990 | USA, America | Case–control | RIGHT COLON Cases: 251 Controls: 367 RECTUM Cases: 393 Controls: 625 |

<60– > 80 | Males | 3 | -Right colon cancer -Rectum cancer |

| Freudenheim et al., 1990 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 422 (34.4) Controls: 844 |

>40 | General population | 8 | -Rectal cancer |

| Meyer et al., 1993 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 424 Controls: 414 |

Cases: 54.9 (NR) Controls: 54.4 (NR) |

General population | 4 | -Colon cancer |

| Newcomb et al., 1993 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 779 Controls: 2315 |

Cases: 65.5 (8.8) Controls: 58.6 (10.9) |

Females | 1 | -Colon cancer -Rectal cancer |

| Gapstur et al., 1994 | USA, America | Cohort | 41,837 | 55–69 | General population | 5 | -Proximal colon -Distal colon -Rectal |

| Goldbohm et al., 1994 | Netherlands, Europe | Cohort | 120,852 (50.52) | 55–69 | General population | 3.3 | -Colon -Rectal |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||||

| Sharpe et al., 2002 | Canada, America | Case–control | Cases: 585

|

35–70 | General population | 6 | -Proximal colon -Distal colon -Rectum |

| Pedersen et al., 2003 | Denmark, Europe | Cohort | 29,132 (46.82) | 23–95 | The Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies is based on three comprehensive Danish programmes of prospective population studies: the Copenhagen City Heart Study, the Copenhagen County Centre of Preventive Medicine (formerly, the Glostrup Population Studies) which includes six cohorts, and the Copenhagen Male Study. | 14.7 | -Colon cancer -Rectal cancer |

| Bongaerts et al., 2008 | Netherlands, Europe | Cohort | 120,852 (50.52) | 55–69 | General population | 13.3 | -Overall colorectum -Colon -Proximal colon -Distal colon -Rectosigmoid -Rectum |

| Crockett et al., 2011 | USA, America | Case–control | Cases: 1033 (43.5) Controls: 1011 (41.0) |

Cases: 40–79 Controls: 40–79 |

NCCCS-II | 5 | -Rectum cancer -Rectosigmoid cancer -Sigmoid cancer |

| Cancer in general | |||||||

| Gong et al., 2009 | USA, America | Cohort | 10,920 (0) | <60, 60–69, and ≥ 70 | General population | 7 | Cancer in general |

| Smyth et al., 2015 | Canada, America | Cohort | 155,875 | 35–70 | PURE study | 4.3 | Cancer in general |

| Schutte et al., 2021 | United Kingdom, Europe | Cohort | 446,439 (53.8) | 56.4 (8.1) | General population | 4 | Cancer in general |

| Glioma | |||||||

| Ryan et al., 1992 | Australia, Oceania | Case–control | Cases: -Glioma: 110 -Meningioma: 60 Controls: 417 |

25–74 | ADELAIDE ADULT BRAIN TUMOR STUDY 1987–90 | 3 | -Glioma -Meningioma |

| Hurley et al., 1996 | Australia, Oceania | Case–control | Cases: 416 (40) Controls: 422 (40.3) |

Cases: 48.9 (14.3) Controls: 50.2 (14.3) |

Melbourne adult brain tumor study | 4 | Glioma cancer |

| Efird et al., 2004 | USA, America | Cohort | 142,085 | 25– > 65 | KPMCP-NC | 21 years; Mean 13.2 ± 6.7 |

Glioma cancer |

| Baglietto et al., 2010 | Australia, Oceania | Cohort | 41,514 (59) | 27–81 | Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study | 15 | Glioblastoma |

* Age: in mean (SD) or range as reported in the studies. USA, United States; NA, Not applicable; NR, Not reported; NBSS, Canadian National Breast Screening Study; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NLCS, The Netherlands Cohort Study; NHEFS, Epidemiologic Follow-up Study; PROMEN STUDY, study of prostate cancer and hormones and alcohol intake; NIH-AARP, National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study; CTS, California Teachers Study; OVAL-BC, Ovarian Cancer in Alberta and British Columbia; EAC, Esophageal adenocarcinoma; EGJAG, Esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma; ESCC, Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; BCC, Basal cell carcinoma; SCC, Squamous cell carcinoma; NCCCS-II, The North Carolina Colon Cancer Study-Phase II; KPMCP-NC, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California.

The references presented in this table are available in Supplementary material.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the risk of bias for longitudinal studies. This tool consists of eight items divided into three categories: (i) selection, (ii) comparability, and (iii) exposure or outcome (depending on whether it is a case–control or cohort study, respectively). Each study is eligible to receive four stars for selection, three stars for exposure, and two stars for comparability. Cohort studies can receive a maximum score of nine, whereas case–control studies can receive a maximum of eight stars, as case–control studies can score with a maximum of one star in the comparability category. A higher score on this scale indicates a lower risk of bias (25).

Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments were performed by two independent reviewers (ML-LT and CA-B). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or with the intervention of a third investigator (IC-R).

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

A meta-analysis was conducted to analyze the association between wine consumption and the risk of developing different types of cancer after classifying studies according to the reported cancer type. When two studies included data from the same sample, we included the study with the larger sample size in the meta-analysis. A 5-year follow-up of the included studies was set as an inclusion criterion for the meta-analysis to ensure data quality. Regarding gynecological cancers, we studied breast and ovarian cancer separately since they are influenced by different risk factors and have different prevalence rates; breast cancer is more prevalent than ovarian cancer (17). The reported relative risk (RR) and odds ratios (OR) were both included in the meta-analysis (26). However, when studies reported the hazard ratio (HR), it was converted to RR using the following formula: RR = (1 -eHRln(1 – r))/r (26).

The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects (27) models were used to calculate the pooled RR and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each type of cancer. The Cochrane Handbook recommendations were used to examine inconsistency, with ranges from 0 to 100% (28). According to the I2, inconsistency was considered unimportant (0–30%), moderate (≥30–50%), substantial (≥50–75%), or considerable (≥75–100%). Corresponding p values were considered. In addition, the τ2 test was used to assess heterogeneity and was interpreted as low when it was below 0.04, moderate when it ranged from ≥0.04 to 0.14, and substantial when it ranged from ≥0.14 to 0.40 (29).

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the summary estimates, eliminating each study one by one from the pooled estimates. Subgroup analyses were performed according to the continent. Random effects meta-regression analyses were used to address whether participants’ mean age, follow-up and percentage of female, whenever possible, as continuous variables, of wine exposure could modify the association of wine consumption and different types of cancer (ovarian, breast, colorectal and renal cancer). Finally, publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression asymmetry test (30), where a p value of <0.10 determined whether significant publication bias existed.

All statistical analyses were conducted with STATA SE software, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States).

Results

Systematic review

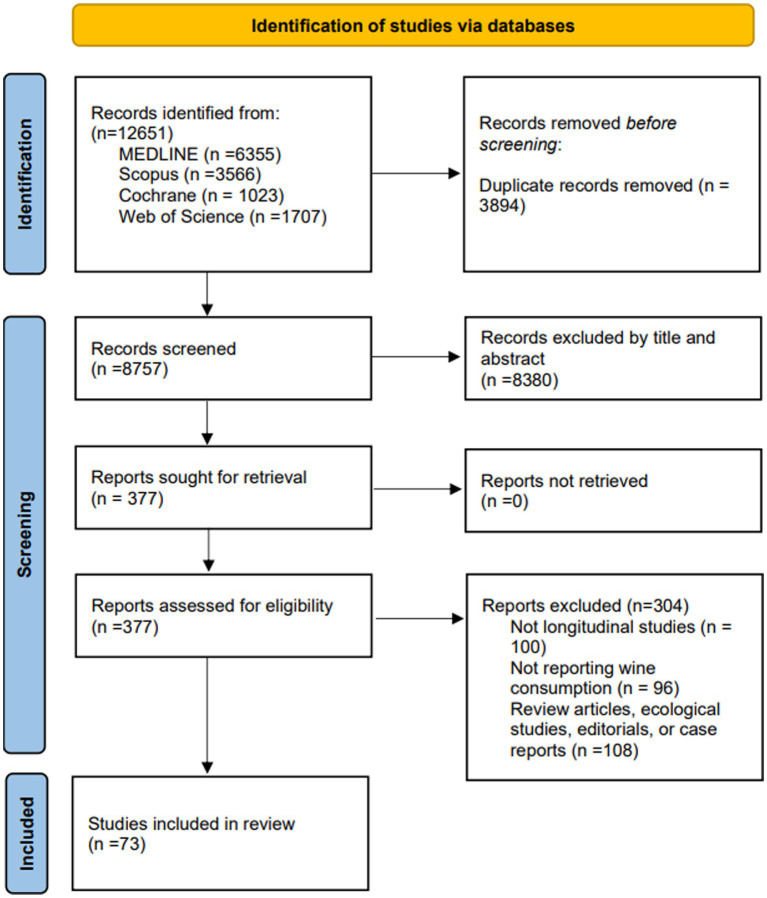

The literature search retrieved 12,651 studies; 8,380 were excluded in the title and abstract review, and 377 were selected for the eligibility assessment. From those, 73 (31–103) studies were included in the systematic review and 26 (31, 34–37, 41, 42, 44, 48, 50, 52, 56, 59, 67, 72, 74, 77, 79, 87–90, 92, 96, 102, 103) in the meta-analysis (Figure 1). The reasons for excluding studies are specified in the flow chart and Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews including database searches.

Of the included studies, 31 (31–61) were cohort studies, and 42 (62–103) were case–control studies. The studies were conducted in 19 different countries: the USA (30) (31, 34, 36, 38–41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 53, 55, 56, 58, 59, 62, 63, 67, 68, 75, 76, 78, 81, 82, 92, 94, 98, 99, 102), New Zealand (1) (71), Australia (8) (51, 57, 64, 70, 73, 80, 93, 101), Canada (8) (37, 60, 70, 74, 86, 89, 97, 103), Greece (2) (50, 70), Argentina (1) (70), Uruguay (2) (79, 85), Italy (11) (50, 65, 66, 69, 70, 72, 77, 84, 87, 88, 96), Netherlands (6) (32, 35, 44, 50, 52, 54), Hawaii (1) (90), Denmark (4) (33, 42, 46, 50), Puerto Rico (1) (91), the United Kingdom (2) (50, 61), Germany (1) (50), France (1) (50), Sweden (5) (47, 50, 83, 95, 100), Spain (1) (50), and Norway (1) (50). The studies were published between 1986 and 2021 with a total sample of 4,346,504 subjects aged between 18 and 103 years. The follow-up period reported by the cohort studies ranged from 2 (41) to 24 years (58). The studies were classified by the type of cancer reported; 11 studies reported information on breast cancer (36, 39, 41, 50, 51, 56, 63, 70, 71, 74, 78), 14 on prostate cancer (34, 35, 38, 45, 46, 77, 79, 82, 83, 86, 94–96, 98), four on renal cell cancer (47, 59, 88, 100), five on pancreatic cancer (39, 54, 55, 58, 84), 10 on ovarian cancer (44, 48, 62, 72, 87, 90, 92, 93, 93, 103), eight on upper airway cancers (33, 46, 65, 66, 69, 85, 91, 101), two on skin cancer (40, 51), one on lung cancer (97), 11 on colorectal cancers (31, 32, 42, 52, 64, 67, 68, 75, 76, 89, 102), and four on glioma (43). The studies reported wine consumption differently (31–63, 65–82, 84–103); 71 studies reported frequency and amount of consumption; four studies reported on whether wine was consumed or not (64, 73, 80, 83). In addition, 15 reported on consumption in oz (31, 36–39, 67, 78, 81, 82, 84, 90–92, 94, 98); 32 studies reported consumption in grams of ethanol (31, 35, 39, 40, 44, 45, 47–50, 52–54, 57, 59, 62, 63, 68, 74–76, 78, 84, 86, 87, 93, 95, 96, 99–102), 18 studies reported wine consumption in milliliters (32, 54, 55, 65, 66, 69, 72, 77, 79, 82, 84, 85, 87, 90, 91, 95, 96, 100); one study reported in standard drinking unit (51) and one study reported the % of ethanol (70). Information on the included studies is shown in Table 1. Finally, a different set of covariates was used to adjust the analyses reported by the included studies (Supplementary Table S3).

Risk of bias assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the risk of bias of the cohort studies. The total score of the included studies ranged from seven to nine stars. Only four studies did not have the highest score in the selection category (32, 40, 48, 59). In the comparability category, all studies scored the highest. Finally, in the outcome category there were four studies with one star (39, 47, 48, 61), 16 studies with two stars (31, 32, 38, 40–44, 48, 50–55, 58, 60), and the rest with three stars (33–37, 45, 46, 56, 57, 59) (Supplementary Table S4).

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the risk of bias of the case–control studies. The total score of the included studies ranged from six to eight stars. In the selection category, one study scored two stars (66), nine studies scored three stars (69, 70, 72, 84, 85, 88, 89, 96, 103), and the remaining studies scored the maximum (62–65, 67, 68, 71, 73–83, 86, 87, 90–95, 97, 102). In the comparability category, all studies scored the highest. Finally, in the outcome category, 10 studies (65, 67, 70, 89, 93, 95, 99, 100, 101, 103) scored one star and the remaining included studies scored two stars (62–64, 66, 68, 69, 71–88, 90–92, 94, 96–98, 102) (Supplementary Table S5).

Meta-analysis

Association between wine consumption and breast and ovarian cancer

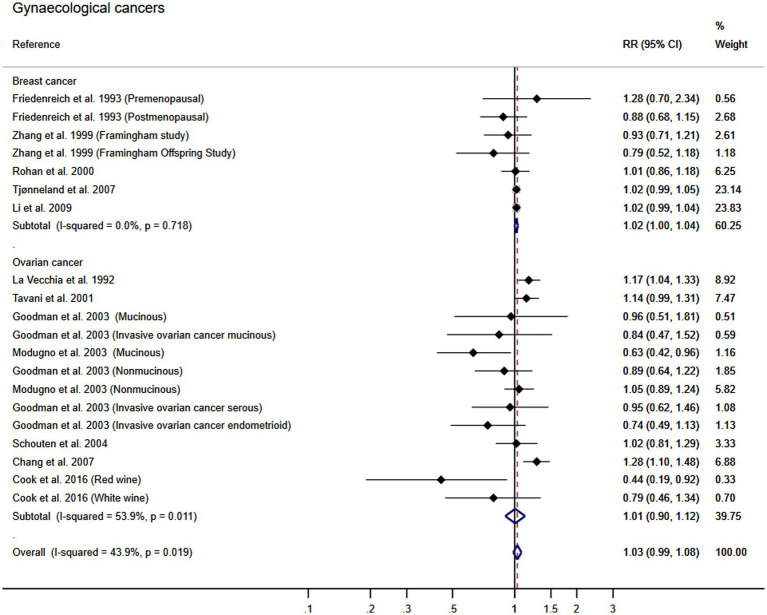

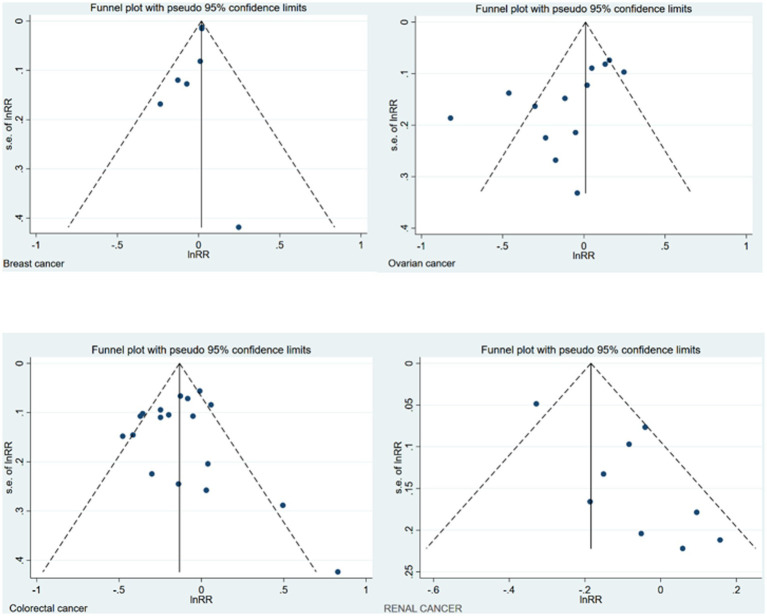

Using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models, the pooled RR for gynecological cancers was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.08; I2: 43.9% τ2: 0.0021). Furthermore, the pooled RR for the association between wine consumption and the development of breast cancer was 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.04). That of ovarian cancer was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.90, 1.12). The heterogeneity of these estimates was unimportant for breast cancer and substantial for ovarian cancer (I2: 0% τ2: 0.0000; and I2: 54% τ2: 0.0173, respectively) (Figure 2). Finally, no publication bias for breast was found using Egger’s test, but publication bias was found for ovarian cancer (p = 0.141, p = 0.021; respectively). The asymmetry in the funnel plot was confirmed for ovarian cancer (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between wine consumption and gynecological cancers. Horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of the study, and the black boxes represent the effect size of each study.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of the different cancers.

Association between wine consumption and colorectal cancer

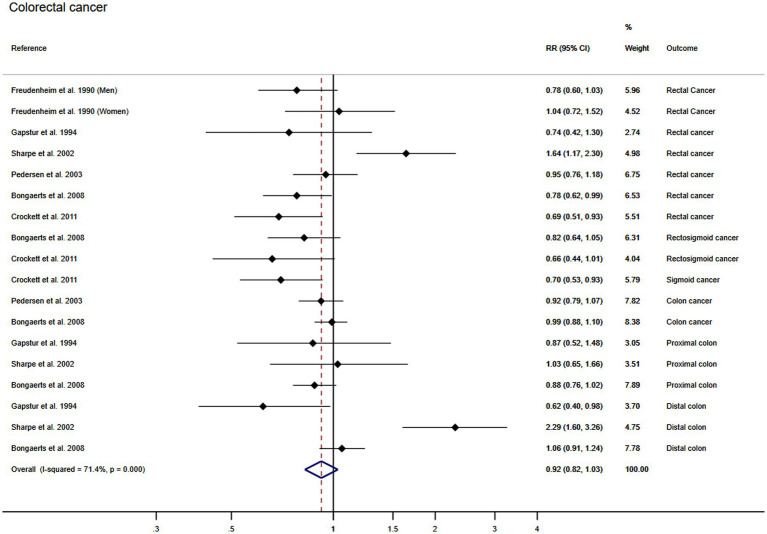

Using the DerSimonian and Laird random effect models, the pooled RR for the association between wine consumption and the colorectal cancer was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.03). The heterogeneity of these estimates was substantial (I2: 71.4% τ2: 0.0356) (Figure 4). Finally, publication bias was not found through Egger’s test for the association between wine consumption and colorectal (p = 0.884) cancer.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the association between wine consumption and colorectal cancer. Horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of the study, and the black boxes represent the effect size of each study.

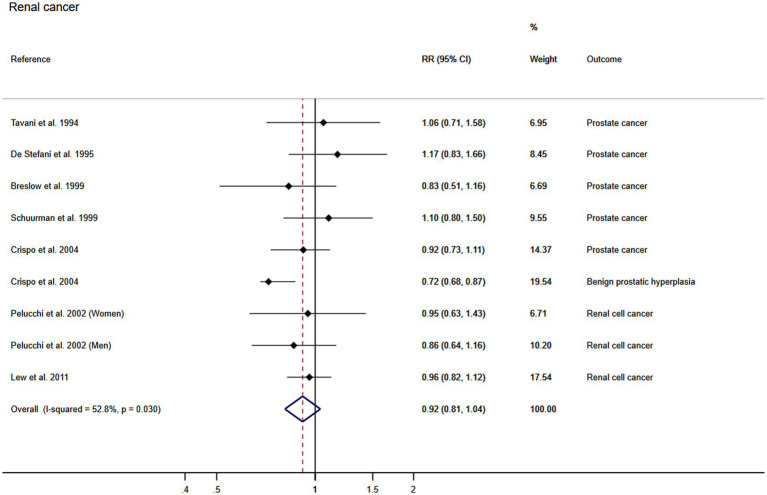

Association between wine consumption and renal cancer

Using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models, the pooled RR for the association between wine consumption and the development of renal cancer was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.04). The heterogeneity of this estimate was substantial (I2: 52.8% τ2: 0.0169) (Figure 5). Finally, publication bias was found through Egger’s test for the association between wine consumption and renal cancer (p = 0.021) and the funnel plot presented the asymmetry (Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the association between wine consumption and renal cancer. Horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of the study, and the black boxes represent the effect size of each study.

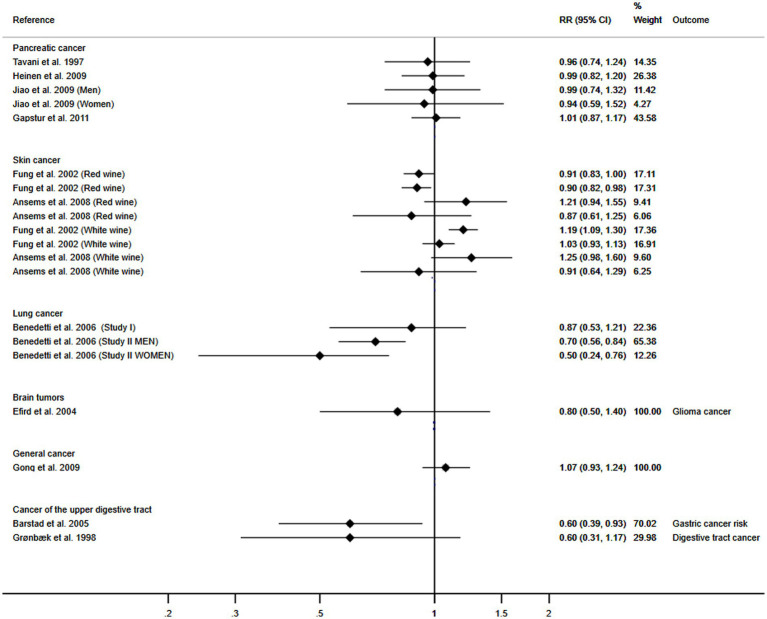

Association between wine consumption and pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, upper digestive tract and general cancer

The number of included studies focusing on these cancers was insufficient to perform a meta-analysis; therefore, a graphical representation is shown. The trend demonstrates a protective association between wine consumption and the development of pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, upper digestive tract and general cancer (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the association between wine consumption and pancreatic, skin, lung, brain and general cancer. Horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals of the study, and the black boxes represent the effect size of each study.

Sensitivity analysis

The pooled RR estimations for the association of wine consumption with the development of different types of cancer were not significantly modified (in magnitude or direction) when data from individual studies were removed from the analysis one by one (Supplementary Table S6).

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression models

When subgroup analyses were performed according to the continent where studies were conducted, the pooled RR estimate showed no significant differences for the different types of cancer (Supplementary Table S7). Random-effects meta-regression models showed that follow up could influence the pooled RR estimate for the association between wine consumption and renal cancer (p = 0.048) and colorectal cancer (p = 0.023) (Supplementary Table S8).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the association between wine consumption and the development of different types of cancer. Meta-regressions were performed to determine whether the association of wine with different types of cancer could be modified by individual and study characteristics including follow-up time, percentage of women, and mean age of participants. Subgroup analyses were performed to depict whether there were differences between continents. Our results indicate no association between wine consumption and the development of general cancer or upper digestive tract, colorectal, renal, pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, and gynecological cancer. Furthermore, no differences were observed after subgroup analyses and meta-regression showed that follow-up could only influence the association between wine consumption and renal and colorectal cancer.

No association was found between wine consumption and the risk of developing gynecological cancer. Evidence has suggested that the greater the amount of alcohol consumption is, the greater the risk of developing breast cancer will be (104); the risk of breast cancer has shown to be increased two-fold among premenopausal women engaging in high alcohol consumption (36), and this risk has also been observed among early consumers of beer and spirits. However, other studies have reported no positive or negative association between wine consumption and breast cancer (36, 37, 63), and additional studies have demonstrated a protective effect of red wine consumption during adolescence and early adulthood on mammographic density (105). Mammographic density benefits have also been associated with white wine consumption (106) among postmenopausal women (107). In addition, our data do not show any association between wine consumption and ovarian cancer risk. Previous evidence has suggested an inverse association between wine consumption and the risk of developing ovarian cancer (90, 93), which is stronger for red wine (103). The possible inverse association could be due to the specific components of wine, such as antioxidants and/or phytoestrogens. In the case of breast cancer, this is a chemo-preventive effect that reduces tumor methylation (108).

Our analyses revealed no association between wine consumption and the risk of developing renal cancer, although previous evidence has shown that moderate wine intake is associated with a lower risk of renal cancer. This protective trend has been observed for both red and white wine (100), and has been found to be stronger among postmenopausal women (47). In the case of prostate cancer, evidence suggests that red wine consumption is associated with decreased risk, particularly regarding aggressive prostate cancer. Our findings did not confirm these assertions.

Gastric cancer has been associated with alcohol consumption for many years, and this association has been reported to be weaker for wine drinkers than for drinkers of other alcoholic beverages (109–111). This observation may be due to the effect of wine on Helicobacter pylori, which is associated with gastric cancer; additionally, the alcohol in wine may increase gastric acidity, which could prevent the growth of different bacterial species (112). Unlike other alcoholic beverages, a moderate daily intake of wine appears to prevent the development of gastric and esophageal cancer (46, 101); however, excessive wine consumption and the consumption of other alcoholic beverages increases this risk (100). Similarly, alcohol consumption has been associated with colon and rectum cancer; however, previous studies have reported an inverse or null relationship between wine consumption and the risk of developing cancer of the colon and rectum (14, 31, 89, 113, 114).

Our results revealed no association between wine consumption and lung cancer. The association between wine consumption and lung cancer has been described as J-shaped, with moderate daily wine drinkers having a lower risk of developing this type of cancer than nondrinkers and heavy drinkers (97). In addition, regarding lung cancer development, it has been shown that there is a concomitant effect of smoking and alcoholic beverage consumption, excluding wine, especially among men (97). However, alcohol consumption has been associated with multiple pathologies, such as pancreatitis. Although pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer (115), alcohol (116) or wine consumption has not been directly linked to pancreatic cancer.

We could not determine the association between wine consumption and the risk of developing other types of cancer. Regarding skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in the fair-skinned population, and its incidence has increased over the last 20 years, with fair skin, hair and eye color being risk factors owing to an increased susceptibility to sunburn (117, 118). Existing evidence shows an inverse association between red wine consumption and skin cancer only in women (40). Regarding brain cancer, alcohol consumption has been shown to be a risk factor due to the ability of alcohol to cross the blood–brain barrier (57, 119, 120). However, a previous meta-analysis demonstrated that this might not be the case for wine, as light wine consumption could prevent cognitive impairment due to the neuroprotective effects of wine components (121, 122).

Many components in wine could have anticarcinogenic effects, such as resveratrol, which plays antioxidant, antimutagenic, and anti-inflammatory roles in carcinogenesis (123). The anti-inflammatory role of resveratrol is found in both acute and chronic phases of the inflammatory process (123). In addition, resveratrol is responsible for inhibiting the cellular process of tumor initiation, promotion, and progression by inhibiting the COX-1 cyclooxygenase activity involved in antitumour promotion (123). Resveratrol provides all these benefits mainly in its trans isoform, which can only be found in peanuts and wine. Resveratrol levels can vary across different wine types depending on the fermentation length. In addition, resveratrol levels are lower in white wine than in red wine because the skins of white grapes are removed before fermentation (124). Other components with anticarcinogenic properties are anthocyanins, quercetin, and tannins, all of which have been shown to protect against ultraviolet radiation, acting on free radicals, suppressing the activity of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and acting against the enzyme myeloperoxidase, thus preventing the development of skin cancer (125–127).

The analyses included in this meta-analysis are adjusted by different covariables, many of them related to healthy behaviors. A healthy dietary pattern is associated with a lower incidence of cardiometabolic events, including wine consumption (128), possibly because alcoholic beverage preference is related to socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and diet (129). In comparison with other alcoholic beverages (129), wine consumption is associated with healthier lifestyles, increased physical activity (130), and less smoking (131). Our analyses could not determine whether these factors influenced the relationship between wine consumption and cancer development. Moreover, the combination of all these factors could be the reason for the greater health benefits (129).

This systematic review and meta-analysis has some limitations that should be mentioned. First, while the WHO sets light-moderate consumption at 20 grams of ethanol per day for men and 10 grams of ethanol per day for women, there is no common definition of wine consumption across studies, the included studies differed in the methods used to measure wine consumption and did not report the specific volume of wine consumed. Reporting the alcohol consumption using the same units is needed to properly determine its effect in different populations. The lack of globally agreed recommendations or safe drinking limits could be a limitation in addressing this issue. Second, the literature search was conducted in English and Spanish and did not include gray literature, which may have missed some potential articles for our study. Thirdly, after assessing the risk of bias in the cohort studies, it was found that many of the studies did not provide a proper outcome assessment, as they were often self-reported by the participants, thus increasing the risk of bias. Regarding the risk of bias in case–control studies, there were studies that selected controls from hospital samples and there were also studies that did not assess the outcome correctly, either because it was not blinded or because it was self-reported, these reasons could decrease the quality of our study. Fourth, meta-regressions by relevant participant characteristics, including the percentage of women, the mean age, or the follow-up time, could not be performed in certain types of cancer due to the lack of data, this could influence the quality of our results as we cannot depict whether the association of wine with certain cancers could be modified by characteristics of the participants or of the study. Fifth, our results may be influenced by confounding variables such as diet, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle although the most covariate-adjusted analyses were selected to try to avoid the influence of other covariates. Sixth, the heterogeneity of the confounding factors adjusted for in each study must be considered a limitation. Finally, due to a lack of data, the association between wine consumption and the development of different cancers could not be analyzed by type of wine or sex, it would be interesting to know which type of wine provides the greatest benefits and whether there is a difference in these benefits according to gender.

In summary, this systematic review and meta-analysis revealed no association between wine consumption and general, upper digestive tract, colorectal, renal, pancreatic, skin, lung, brain, and gynecological cancers. Caution should always be exercised in populations most vulnerable to alcohol consumption or those with pathologies. Finally, more research is needed to evaluate wine consumption independently from that of other alcoholic beverages, and guidelines for safe wine consumption should be included in health recommendations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ML-L-T and CÁ-B: conceptualization, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation. ML-L-T, CÁ-B, and IC-R: methodology. IC-R and CÁ-B: software. CP-M and BB-P: validation and visualization. ML-L-T and IC-R: formal analysis. ML-L-T, BB-P, and CP-M: resources. CÁ-B and VM-V: data curation. VM-V: writing—review and editing. CÁ-B: supervision. All authors revised and approved the final version of the articles.

Funding

This research was funded by FEDER funds. ML-L-T was supported by a grant from the University of Castilla-La Mancha (2022-PROD-20657). BB-P was supported by a grant from the University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain, co-financed by the European Social Fund (2020-PREDUCLM-16746). CP-M was supported by a grant from the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (2018-CPUCLM-7939).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1197745/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, McGaughey M, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet. (2018) 392:2052–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Kocarnik JM, Compton K, Dean FE, Fu W, Gaw BL, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. JAMA Oncol. (2022) 8:420–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study [published correction appears in lancet. 2020 Sep 12;396(10253):758]. Lancet. (2020) 395:1907–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2019 Cancer Risk Factors Collaborators . The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010-19: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2022) 400:563–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01438-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldewijns MM, van Vlodrop IJ, Schouten LJ, Soetekouw PM, de Bruïne AP, van Engeland M. Genetics and epigenetics of renal cell cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2008) 1785:133–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.12.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herity B, Moriarty M, Daly L, Dunn J, Bourke GJ. The role of tobacco and alcohol in the aetiology of lung and larynx cancer. Br J Cancer. (1982) 46:961–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.308, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viner B, Barberio AM, Haig TR, Friedenreich CM, Brenner DR. The individual and combined effects of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking on site-specific cancer risk in a prospective cohort of 26,607 adults: results from Alberta’s tomorrow project. Cancer Causes Control. (2019) 30:1313–26. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01226-7, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC] . Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Alcohol drinking. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; (1988). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loprieno N. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risk of chemicals to man: "relevance of data on mutagenicity". Mutat Res. (1975) 31:210. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H, Ferrari P, Sornpaisarn B, Obot I, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:1071–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. (2015) 112:580–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health . Low risk drinking limits for alcohol. Update of risk related to levels of alcohol consumption, drinking pattern and type of drinking. Madrid: Ministry of Health; (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galeone C, Malerba S, Rota M, Bagnardi V, Negri E, Scotti L, et al. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of brain tumours. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:514–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds432, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longnecker MP, Orza MJ, Adams ME, Vioque J, Chalmers TC. A meta-analysis of alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. (1990) 1:59–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00053184, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeiffer RM, Park Y, Kreimer AR, Lacey JV, Pee D, Greenlee RT, et al. Risk prediction for breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in white women aged 50 y or older: derivation and validation from population-based cohort studies. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001492, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD. The calculation of breast cancer risk for women with a first degree family history of ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (1993) 28:115–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00666424, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kukafka R, Pan S, Silverman T, Zhang T, Chung WK, Terry MB, et al. Patient and clinician decision support to increase genetic counselling for hereditary breast and ovarian Cancer syndrome in primary care: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2222092. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22092, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Friedman GD, Hiatt RA. The relations of alcoholic beverage use to colon and rectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. (1988) 128:1007–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115045, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stemmermann GN, Nomura AM, Chyou PH, Yoshizawa C. Prospective study of alcohol intake and large bowel cancer. Dig Dis Sci. (1990) 35:1414–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01536750, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, Polychronopoulos E, Xinopoulos D, Linos A, et al. Alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer in a Mediterranean population: a case–control study. Dis Colon Rectum. (2012) 55:703–10. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31824e612a, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandeya N, Williams G, Green AC, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Australian Cancer Study . Alcohol consumption and the risks of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. (2009) 136:1215–e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.052, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott E, Grønbaek M, Becker U, Sørensen TI. Alcohol intake and the risk of lung cancer: influence of type of alcoholic beverage. Am J Epidemiol. (1999) 149:463–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009834, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Green S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available at: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org.

- 24.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Petersen J, Welch Losos D, et al. Newcastle -Ottawa quality assessment scale case control studies. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. (2023). Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf (Accessed July 17, 2023).

- 26.Sxtare J, Maucort-Boulch D. Odds ratio, hazard ratio and relative risk. Metodoloski zvezki. (2016) 13:59–67. doi: 10.51936/uwah2960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. (2007) 28:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stettler C, Allemann S, Wandel S, Kastrati A, Morice MC, Schomig A, et al. Drug eluting and bare metal stents in people with and without diabetes: collaborative network meta-analysis. BMJ. (2008) 337:a1331. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1331, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. (2001) 323:101–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gapstur SM, Potter JD, Folsom AR. Alcohol consumption and colon and rectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Int J Epidemiol. (1994) 23:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldbohm RA, Van den Brandt PA, Van’t Veer P, Dorant E, Sturmans F, Hermus RJ. Prospective study on alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer of the colon and rectum in the Netherlands. Cancer Causes Control. (1994) 5:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grønbaek M, Becker U, Johansen D, Tønnesen H, Jensen G, Sørensen TI. Population based cohort study of the association between alcohol intake and cancer of the upper digestive tract. BMJ. (1998) 317:844–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breslow RA, Wideroff L, Graubard BI, et al. Alcohol and prostate cancer in the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of the United States. Ann Epidemiol. (1999) 9:254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuurman AG, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. A prospective cohort study on consumption of alcoholic beverages in relation to prostate cancer incidence (The Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control. (1999) 10:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Kreger BE, Dorgan JF, Splansky GL, Cupples LA, Ellison RC. Alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer: the Framingham Study revisited. Am J Epidemiol. (1999) 149:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohan TE, Jain M, Howe GR, Miller AB. Alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer: a cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. (2000) 11:239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Putnam SD, Cerhan JR, Parker AS, et al. Lifestyle and anthropometric risk factors for prostate cancer in a cohort of Iowa men. Ann Epidemiol. (2000) 10:361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Coffee and alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer in two prospective United States cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2001) 10:429–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fung TT, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Intake of alcohol and alcoholic beverages and the risk of basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2002) 11:1119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horn-Ross PL, Hoggatt KJ, West DW, et al. Recent diet and breast cancer risk: the California Teachers Study (USA). Cancer Causes Control. (2002) 13:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen A, Johansen C, Grønbaek M. Relations between amount and type of alcohol and colon and rectal cancer in a Danish population based cohort study. Gut. (2003) 52:861–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Efird JT, Friedman GD, Sidney S, et al. The risk for malignant primary adult-onset glioma in a large, multiethnic, managed-care cohort: cigarette smoking and other lifestyle behaviors. J Neurooncol. (2004) 68:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schouten LJ, Zeegers MP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Alcohol and ovarian cancer risk: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control. (2004) 15:201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Alcohol intake, drinking patterns, and risk of prostate cancer in a large prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. (2004) 159:444–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barstad B, Sørensen TI, Tjønneland A, et al. Intake of wine, beer and spirits and risk of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. (2005) 14:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rashidkhani B, Akesson A, Lindblad P, Wolk A. Alcohol consumption and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a prospective study of Swedish women. Int J Cancer. (2005) 117:848–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang ET, Canchola AJ, Lee VS, et al. Wine and other alcohol consumption and risk of ovarian cancer in the California Teachers Study cohort. Cancer Causes Control. (2007) 18:91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sutcliffe S, Giovannucci E, Leitzmann MF, et al. A prospective cohort study of red wine consumption and risk of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. (2007) 120:1529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tjønneland A, Christensen J, Olsen A, et al. Alcohol intake and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Cancer Causes Control. (2007) 18:361–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ansems TM, van der Pols JC, Hughes MC, Ibiebele T, Marks GC, Green AC. Alcohol intake and risk of skin cancer: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2008) 62:162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bongaerts BW, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, de Goeij AF, Weijenberg MP. Alcohol consumption, type of alcoholic beverage and risk of colorectal cancer at specific subsites. Int J Cancer. (2008) 123:2411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gong Z, Kristal AR, Schenk JM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Thompson IM. Alcohol consumption, finasteride, and prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Cancer. (2009) 115:3661–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heinen MM, Verhage BA, Ambergen TA, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Alcohol consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer in the Netherlands cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. (2009) 169:1233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiao L, Silverman DT, Schairer C, et al. Alcohol use and risk of pancreatic cancer: the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. (2009) 169:1043–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Baer D, Friedman GD, Udaltsova N, Shim V, Klatsky AL. Wine, liquor, beer and risk of breast cancer in a large population. Eur J Cancer. (2009) 45:843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baglietto L, Giles GG, English DR, Karahalios A, Hopper JL, Severi G. Alcohol consumption and risk of glioblastoma; evidence from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Int J Cancer. (2011) 128:1929–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gapstur SM, Jacobs EJ, Deka A, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Thun MJ. Association of alcohol intake with pancreatic cancer mortality in never smokers. Arch Intern Med. (2011) 171:444–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lew JQ, Chow WH, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Park Y. Alcohol consumption and risk of renal cell cancer: the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Br J Cancer. (2011) 104:537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smyth A, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease, cancer, injury, admission to hospital, and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. (2015) 386:1945–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schutte R, Smith L, Wannamethee G. Alcohol - The myth of cardiovascular protection. Clin Nutr. (2022) 41:348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gwinn ML, Webster LA, Lee NC, Layde PM, Rubin GL. Alcohol consumption and ovarian cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. (1986) 123:759–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harvey EB, Schairer C, Brinton LA, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JF, Jr. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1987) 78:657–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Potter JD, McMichael AJ. Diet and cancer of the colon and rectum: a case–control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1986) 76:557–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barra S, Franceschi S, Negri E, Talamini R, La Vecchia C. Type of alcoholic beverage and cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx and oesophagus in an Italian area with high wine consumption. Int J Cancer. (1990) 46:1017–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franceschi S, Talamini R, Barra S, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus in northern Italy. Cancer Res. (1990) 50:6502–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freudenheim JL, Graham S, Marshall JR, Haughey BP, Wilkinson G. Lifetime alcohol intake and risk of rectal cancer in western New York. Nutr Cancer. (1990) 13:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Longnecker MP. A case–control study of alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of cancer of the right colon and rectum in men. Cancer Causes Control. (1990) 1:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barra S, Barón AE, Franceschi S, Talamini R, La Vecchia C. Cancer and noncancer controls in studies on the effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption. Int J Epidemiol. (1991) 20:845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Howe G, Rohan T, Decarli A, et al. The association between alcohol and breast cancer risk: evidence from the combined analysis of six dietary case–control studies. Int J Cancer. (1991) 47:707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sneyd MJ, Paul C, Spears GF, Skegg DC. Alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. (1991) 48:812–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Parazzini F, Gentile A, Fasoli M. Alcohol and epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. (1992) 45:1025–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryan P, Lee MW, North B, McMichael AJ. Risk factors for tumors of the brain and meninges: results from the Adelaide Adult Brain Tumor Study. Int J Cancer. (1992) 51:20–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Friedenreich CM, Howe GR, Miller AB, Jain MG. A cohort study of alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. (1993) 137:512–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer F, White E. Alcohol and nutrients in relation to colon cancer in middle-aged adults. Am J Epidemiol. (1993) 138:225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Marcus PM. Cancer of the large bowel in women in relation to alcohol consumption: a case–control study in Wisconsin (United States). Cancer Causes Control. (1993) 4:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tavani A, Negri E, Franceschi S, Talamini R, La Vecchia C. Alcohol consumption and risk of prostate cancer. Nutr Cancer. (1994) 21:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Longnecker MP, Newcomb PA, Mittendorf R, et al. Risk of breast cancer in relation to lifetime alcohol consumption. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1995) 87:923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De Stefani E, Fierro L, Barrios E, Ronco A. Tobacco, alcohol, diet and risk of prostate cancer. Tumori. (1995) 81:315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hurley SF, McNeil JJ, Donnan GA, Forbes A, Salzberg M, Giles GG. Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors for glioma: a case–control study in Melbourne. Australia. J Epidemiol Community Health. (1996) 50:442–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Swanson CA, Coates RJ, Malone KE, et al. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk among women under age 45 years. Epidemiology. (1997) 8:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hayes RB, Brown LM, Schoenberg JB, et al. Alcohol use and prostate cancer risk in US blacks and whites. Am J Epidemiol. (1996) 143:692–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andersson SO, Baron J, Bergström R, Lindgren C, Wolk A, Adami HO. Lifestyle factors and prostate cancer risk: a case–control study in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (1996) 5:509–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tavani A, Pregnolato A, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Alcohol consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer. Nutr Cancer. (1997) 27:157–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Oreggia F, Fierro L, Mendilaharsu M. Hard liquor drinking is associated with higher risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx than wine drinking. A case–control study in Uruguay. Oral Oncol. (1998) 34:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jain MG, Hislop GT, Howe GR, Burch JD, Ghadirian P. Alcohol and other beverage use and prostate cancer risk among Canadian men. Int J Cancer. (1998) 78:707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tavani A, Gallus S, Dal Maso L, et al. Coffee and alcohol intake and risk of ovarian cancer: an Italian case–control study. Nutr Cancer. (2001) 39:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pelucchi C, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Talamini R, Franceschi S. Alcohol drinking and renal cell carcinoma in women and men. Eur J Cancer Prev. (2002) 11:543–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharpe CR, Siemiatycki J, Rachet B. Effects of alcohol consumption on the risk of colorectal cancer among men by anatomical subsite (Canada). Cancer Causes Control. (2002) 13:483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goodman MT, Tung KH. Alcohol consumption and the risk of borderline and invasive ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. (2003) 101:1221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang WY, Winn DM, Brown LM, et al. Alcohol concentration and risk of oral cancer in Puerto Rico. Am J Epidemiol. (2003) 157:881–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Modugno F, Ness RB, Allen GO. Alcohol consumption and the risk of mucinous and nonmucinous epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. (2003) 102:1336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Webb PM, Purdie DM, Bain CJ, Green AC. Alcohol, wine, and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2004) 13:592–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barba M, McCann SE, Schünemann HJ, et al. Lifetime total and beverage specific--alcohol intake and prostate cancer risk: a case–control study. Nutr J. (2004) 3:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chang ET, Hedelin M, Adami HO, Grönberg H, Bälter KA. Alcohol drinking and risk of localized versus advanced and sporadic versus familial prostate cancer in Sweden. Cancer Causes Control. (2005) 16:275–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crispo A, Talamini R, Gallus S, et al. Alcohol and the risk of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. (2004) 64:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Benedetti A, Parent ME, Siemiatycki J. Consumption of alcoholic beverages and risk of lung cancer: results from two case–control studies in Montreal. Canada. Cancer Causes Control. (2006) 17:469–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schoonen WM, Salinas CA, Kiemeney LA, Stanford JL. Alcohol consumption and risk of prostate cancer in middle-aged men. Int J Cancer. (2005) 113:133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peterson NB, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, et al. Alcohol consumption and ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case–control study. Int J Cancer. (2006) 119:2423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Greving JP, Lee JE, Wolk A, Lukkien C, Lindblad P, Bergström A. Alcoholic beverages and risk of renal cell cancer. Br J Cancer. (2007) 97:429–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pandeya N, Williams G, Green AC, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Australian Cancer Study . Alcohol consumption and the risks of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. (2009) 136:1215–e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crockett SD, Long MD, Dellon ES, Martin CF, Galanko JA, Sandler RS. Inverse relationship between moderate alcohol intake and rectal cancer: analysis of the North Carolina Colon Cancer Study. Dis Colon Rectum. (2011) 54:887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cook LS, Leung AC, Swenerton K, et al. Adult lifetime alcohol consumption and invasive epithelial ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case–control study. Gynecol Oncol. (2016) 140:277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosenberg L, Slone D, Shapiro S, Kaufman DW, Helmrich SP, Miettinen OS, et al. Breast cancer and alcoholic-beverage consumption. Lancet. (1982) 319:267–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90987-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Flom JD, Ferris JS, Tehranifar P, Terry MB. Alcohol intake over the life course and mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2009) 117:643–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0302-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vachon CM, Kushi LH, Cerhan JR, Kuni CC, Sellers TA. Association of diet and mammographic breast density in the Minnesota breast cancer family cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. (2000) 9:151–60. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Masala G, Ambrogetti D, Assedi M, Giorgi D, Del Turco MR, Palli D. Dietary and lifestyle determinants of mammographic breast density. A longitudinal study in a Mediterranean population. Int J Cancer. (2006) 118:1782–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21558, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhu W, Qin W, Zhang K, Rottinghaus GE, Chen YC, Kliethermes B, et al. Trans-resveratrol alters mammary promoter hypermethylation in women at increased risk for breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. (2012) 64:393–400. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.654926, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Adler G. Inverse graded relation between alcohol consumption and active infection with Helicobacter pylori. Am J Epidemiol. (1999) 149:571–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009854, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. (1999) 94:2373–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01360.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Daroch F, Hoeneisen M, González CL, Kawaguchi F, Salgado F, Solar H, et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of Chilean red wines against Helicobacter pylori. Microbios. (2001) 104:79–85. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jonkers D, Houben P, Hameeteman W, Stobberingh E, de Bruine A, Arends JW, et al. Differential features of gastric cancer patients, either Helicobacter pylori positive or Helicobacter pylori negative. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (1999) 31:836–41. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Park JY, Mitrou PN, Dahm CC, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, et al. Baseline alcohol consumption, type of alcoholic beverage and risk of colorectal cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition-norfolk study. Cancer Epidemiol. (2009) 33:347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pedersen A, Johansen C, Grønbaek M. Relations between amount and type of alcohol and colon and rectal cancer in a Danish population based cohort study. Gut. (2003) 52:861–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.861, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 116.Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, el Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. (2009) 10:1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70326-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stern RS. The mysteries of geographic variability in nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence. Arch Dermatol. (1999) 135:843–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.7.843, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Urbach F. Incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Clin. (1991) 9:751–5. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8635(18)30379-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.IARC . Alcohol consumption and ethyl carbamateed, vol. 96. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 120.Choi NW, Schuman LM, Gullen WH. Epidemiology of primary central nervous system neoplasms. II. Case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. (1970) 91:467–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121158, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, Dugravot A, Akbaraly T, Britton A, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. (2018) 362:k2927. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2927, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lucerón-Lucas-Torres M, Cavero-Redondo I, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Saz-Lara A, Pascual-Morena C, Álvarez-Bueno C. Association between wine consumption and cognitive decline in older people: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:863059. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.863059, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CWW, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. (1997) 275:218–20. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bianchini F, Vainio H. Wine and resveratrol: mechanisms of cancer prevention? Eur J Cancer Prev. (2003) 12:417–25. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200310000-00011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Decean H, Fischer-Fodor E, Tatomir C, Perde-Schrepler M, Somfelean L, Burz C, et al. Vitis vinifera seeds extract for the modulation of cytosolic factors BAX-α and NF-kB involved in UVB-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis of human skin cells. Clujul Med. (2016) 89:72–81. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-508, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kwon JY, Lee KW, Kim JE, Jung SK, Kang NJ, Hwang MK, et al. Delphinidin suppresses ultraviolet B-induced cyclooxygenases-2 expression through inhibition of MAPKK4 and PI-3 kinase. Carcinogenesis. (2009) 30:1932–40. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp216, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vicentini F, Simi T, Delciampo J, Wolga N, Pitol D, Iyomasa M, et al. Quercetin in w/o microemulsion: in vitro and in vivo skin penetration and efficacy against UVB-induced skin damages evaluated in vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. (2008) 69:948–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.01.012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kosti R, Tsiampalis T, Kouvari M, Chrysohoou C, Georgousopoulou E, Skoumas J, et al. Dietary patterns and alcoholic beverage preference in relation to 10-year cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes mellitus incidence in the ATTICA cohort study. OENO One. (2022) 56:121–35. doi: 10.20870/oeno-one.2022.56.3.5457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kosti RI, Di Lorenzo C, Panagiotakos DB, Sandeman G, Frittella N, Iasiello B, et al. Dietary and lifestyle habits of drinkers with preference for alcoholic beverage: does it truly matter for public health? A review of the evidence. OENO One. (2021) 55:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ferreira-Pêgo C, Babio N, Salas-Salvadó J. A higher Mediterranean diet adherence and exercise practice are associated with a healthier drinking profile in a healthy Spanish adult population. Eur J Nutr. (2017) 56:739–48. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1117-5, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.McCann SE, Sempos C, Freudenheim JL, Muti P, Russell M, Nochajski TH, et al. Alcoholic beverage preference and characteristics of drinkers and nondrinkers in western New York (United States). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2003) 13:2–11. doi: 10.1016/S0939-4753(03)80162-X, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data