This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial assesses collaborative dementia care and total Medicare reimbursement costs compared with usual care.

Key Points

Question

Does participation in collaborative dementia care reduce total Medicare reimbursement costs compared with usual care?

Findings

In this prespecified secondary analysis of 460 patients with dementia who were enrolled in the Care Ecosystem randomized clinical trial and had continuous Medicare fee-for-service coverage, a collaborative dementia care program was associated with lower total cost of care compared with usual care.

Meaning

Collaborative dementia care programs provide a cost-effective, high-value model for dementia care.

Abstract

Importance

Collaborative dementia care programs are effective in addressing the needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers. However, attempts to consider effects on health care spending have been limited, leaving a critical gap in the conversation around value-based dementia care.

Objective

To determine the effect of participation in collaborative dementia care on total Medicare reimbursement costs compared with usual care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a prespecified secondary analysis of the Care Ecosystem trial, a 12-month, single-blind, parallel-group randomized clinical trial conducted from March 2015 to March 2018 at 2 academic medical centers in California and Nebraska. Participants were patients with dementia who were living in the community, aged 45 years or older, and had a primary caregiver and Medicare fee-for-service coverage for the duration of the trial.

Intervention

Telehealth dementia care program that entailed assignment to an unlicensed dementia care guide who provided caregiver support, standardized education, and connection to licensed dementia care specialists.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was the sum of all Medicare claim payments during study enrollment, excluding Part D (drugs).

Results

Of the 780 patients in the Care Ecosystem trial, 460 (59.0%) were eligible for and included in this analysis. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 78 (72-84) years, and 256 (55.7%) identified as female. Participation in collaborative dementia care reduced the total cost of care by $3290 from 1 to 6 months postenrollment (95% CI, −$6149 to −$431; P = .02) and by $3027 from 7 to 12 months postenrollment (95% CI, −$5899 to −$154; P = .04), corresponding overall to a mean monthly cost reduction of $526 across 12 months. An evaluation of baseline predictors of greater cost reduction identified trends for recent emergency department visit (−$5944; 95% CI, −$10 336 to −$1553; interaction P = .07) and caregiver depression (−$6556; 95% CI, −$11 059 to −$2052; interaction P = .05).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial among Medicare beneficiaries with dementia, the Care Ecosystem model was associated with lower total cost of care compared with usual care. Collaborative dementia care programs are a cost-effective, high-value model for dementia care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02213458

Introduction

The US health care system is unprepared to meet the needs of the growing population of patients with dementia. Among adults aged 65 years and older, dementia represents the most expensive health condition, costing Medicare an estimated $44 billion annually in 2016.1 Collaborative dementia care models are an effective approach to address the medical and social needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Studies demonstrate that these programs can decrease use of emergency department (ED) services, delay long-term care placement, improve guideline-based quality indicators, improve quality of life for people with dementia, and reduce caregiver strain and depression.2,10,11,12,13,14 Select programs have also examined changes in cost associated with program implementation in smaller cohorts of patients.15,16,17,18 However, rigorous attempts to tie these programs to reductions in total health care spending have been limited, leaving a critical gap in the conversation around value-based dementia care.

The Care Ecosystem is a collaborative dementia care model that uses a multidisciplinary care team centered around an unlicensed, specially trained, dementia care team navigator to provide telehealth-enabled support to patients with dementia and their primary caregiver.10 The Care Ecosystem was studied in a large randomized clinical trial, which demonstrated that program participation improved patient quality of life, reduced ED use, reduced caregiver depression and caregiver burden, and reduced the use of potentially inappropriate medications.2,19 The effect of Care Ecosystem on health care dollars spent has not previously been reported due to delays in claims data access. In this study, we linked Medicare claims to trial data to examine the effect of the Care Ecosystem model on total health care costs.

Methods

Study Design

This was a prespecified secondary analysis of individuals enrolled in the Care Ecosystem trial, a 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, parallel-group randomized clinical trial studying the effect of a telehealth intervention targeting patients with dementia and their caregivers (trial protocol in Supplement 1). The trial was conducted from March 20, 2015, to March 5, 2018. All patient and caregiver dyads provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The rationale and protocol have been previously published.2,10 For the present analysis, we evaluated the effect of the Care Ecosystem on total cost of care. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Study Population, Data, Randomization, and Intervention

Participants were patients aged 45 years or older who were diagnosed with dementia by a health care clinician; were living in the community; had a primary caregiver who agreed to co-enroll; resided in California, Nebraska, or Iowa; and had active or pending enrollment in Medicare or Medicaid. Data sources for this analysis included surveys conducted during the trial, Medicare claims files, and the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. Eligible dyads were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive the Care Ecosystem intervention or usual care. The intervention is described in prior publications2,10 and in the eMethods and eTable 8 in Supplement 2.

Total Cost of Care Outcome

The effectiveness outcome was the total cost of care reimbursed by Medicare during the year that the patient was enrolled in the Care Ecosystem trial. This was calculated as the sum of all Medicare claim payments made for the beneficiary during the 12 months of enrollment (see eMethods in Supplement 2 for details).

Other Measurements

The patient-level variables derived from baseline telephone surveys with the caregivers were age, sex, race, ethnicity, and dementia severity. Race and ethnicity were reported by the caregivers using categories mandated by the National Institutes of Health policy on reporting race and ethnicity. Dementia severity was measured using the Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS), a validated 10-item questionnaire (range 0 to 30) with validated cutoffs of mild (<12.5), moderate (12.5-17.5), and severe dementia (>17.5).20 Patient-level variables that were derived from Medicare claims were the Charlson comorbidity index, monthly Medicare program enrollment in the 12 months preceding and 12 months during trial enrollment, Area Deprivation Index (ADI),21 and rural-urban commuting area22 (eMethods in Supplement 2). Caregiver-level variables that were derived from the telephone survey were caregiver depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PHQ-9)23 and caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview-12).24,25

Statistical Analysis

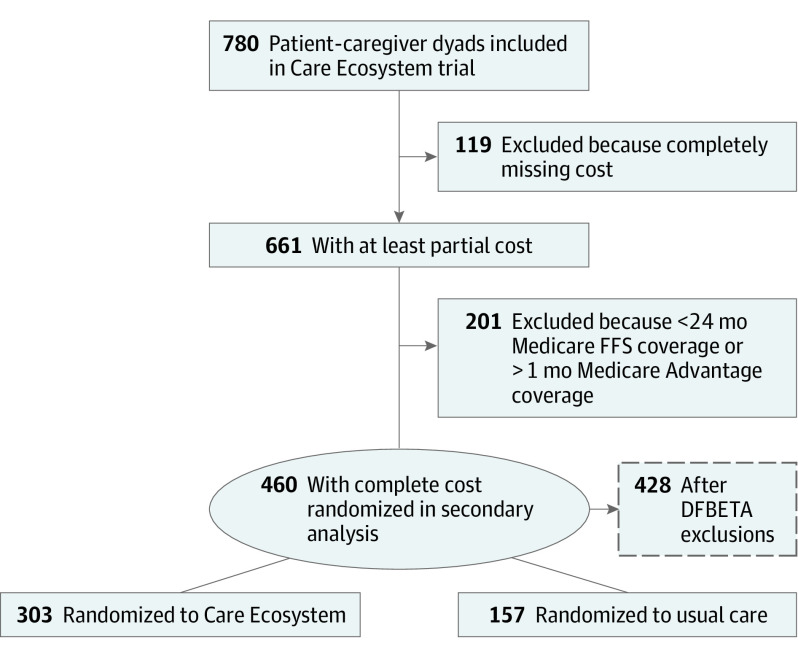

Unlike claims for Medicare FFS beneficiaries, which are directly submitted to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Medicare Advantage (MA) claims are submitted to private-sector insurers who have been inconsistent in passing data back to CMS. This results in incomplete ascertainment of utilization and costs among MA beneficiaries. Among all MA beneficiaries enrolled in the trial, over 60% did not have reimbursement costs captured by Medicare claims files in the 12 months preceding and 12 months during trial enrollment (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).26 To contend with this missingness, we identified the subgroup of patients who had 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage for whom we therefore anticipated complete ascertainment of utilization and costs because point estimates derived from this subgroup would be a more reliable reflection of actual Medicare reimbursement costs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Patients Included in the Main and Secondary Analyses.

FFS indicates fee-for-service.

Our analyses needed to account for the heavily skewed distribution of health care costs (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). The typical distribution of health care costs complicates the ability to accurately estimate costs of a given patient population.27,28 To control for influential observations, we used DFBETAs, which are measures of standardized differences between regression coefficients when a given observation is included or excluded. The DFBETAs were calculated for the coefficient of the 6-month and 12-month Care Ecosystem treatment effects, and the data set was trimmed to only include individuals not exceeding a DFBETA value of 2/√N, or 0.09 (2/√460). This method has been demonstrated to produce estimates of similar magnitude to those produced by the full cohort while demonstrating the most improvement in precision.28,29 This allowed us to model the costs of patients who have more typical engagement with the health care system and not of patients with extreme (eg, catastrophic) health expenditures.

For the primary analysis, we estimated the 6-month and 12-month treatment effects of the Care Ecosystem on total cost of care using a linear mixed-effects model among individuals with 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage and excluding outliers with a DFBETA value above 2/√N. The model was identical to the statistical approach used for our previously published randomized clinical trial reporting survey-based outcomes and defined a priori.2 Specifically, the model included the treatment group, time period (12 months preceding enrollment, 0-6 months postenrollment, 6-12 months postenrollment), baseline dementia severity, and an interaction term between the treatment group and time period as fixed effects and a random effect for the dyad, each of which had 3 repeated measures to define a random slope. This model was selected to account for different levels of benefit by follow-up period and participant-specific random effects.2 By incorporating participant-specific random effects, the model was also able to account for differences in baseline health care costs by intervention group.

The benefit of the Care Ecosystem was hypothesized to vary across dyads in the trial according to patient characteristics (dementia severity and ED use in the 12 months preceding enrollment) and caregiver characteristics (presence of depression, presence of high burden). We formally assessed the heterogeneity of the treatment effect by repeating the primary analysis and incorporating an interaction term that included the designated baseline characteristic. In other words, we fit a linear mixed-effects model with treatment group, time period, and a 3-way interaction term between the treatment group, time period, and the characteristic of interest along with a random effect for the dyad and time period.

In sensitivity analyses, we assessed the robustness of the analysis in multiple ways. To address how we handled missingness, we repeated the primary analysis including (1) patients who died during the trial and thus had less than 24 months of Medicare coverage but had continuous Medicare FFS coverage until the time of death, and (2) patients with linked Medicare claims data who had nonmissing total costs irrespective of their coverage plan, including those covered by MA plans and discontinuous Medicare FFS coverage. To address how we handled right-skewness, we repeated our primary analysis after applying 2 alternative approaches to address skew: trimming and winsorization.28 Trimming involves specifying a threshold to define outlier observations and excluding all observations that are more extreme than the specified threshold. Winsorization involves specifying a threshold and then transforming (as opposed to excluding) more extreme observations so that their values are set equal to the specified threshold. We applied different cutoff points for trimming and winsorization, from the 97.5th to 99.5th percentiles. Lastly, we performed a 2-stage hurdle analysis for patients with 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage including all outliers. For stage 1, we used mixed-effects logistic regression to model patients with any cost vs no cost during the trial period. For stage 2, we excluded patients with zero costs and performed linear mixed-effects regression with a log link function and γ distribution to model total cost of care among patients with any cost. By using the γ distribution, this stage 2 model allowed us to incorporate patients with extreme costs in the analysis. However, it also required transforming the outcome data to fit the distribution and then transforming the data back to an interpretable point estimate, and did not allow for inclusion of patients with zero and any cost in the same analysis.

We considered statistical significance as a 2-tailed P value of less than .05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

A total of 780 dyads participated in the Care Ecosystem trial. Among these dyads, 739 (94.7%) patients had linked Medicare claims and available costs (including MA beneficiaries), and 460 (59.0%) had 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage and no MA for the full 24 months (Figure 1). Among these patients, 303 were randomized to the Care Ecosystem and 157 were randomized to usual care, consistent with the 2:1 ratio in the overall trial. These patients had a median (IQR) age of 78 (72-84) years, 256 (55.7%) identified as female and 204 (44.3%) as male, and the median (IQR) QDRS score was 11.5 (7-16) (Table). Baseline characteristics of dyads with and without continuous Medicare FFS coverage are compared in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Patients with missing costs were more likely to be from a minority racial or ethnic group, live in a metropolitan area, and have more advanced dementia, whereas caregivers for intervention patients with missing costs were more likely to be younger and not a spouse.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Dementia With 24-Month Continuous Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Coverage and Caregivers Enrolled in the Care Ecosystem Triala.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Care Ecosystem | Usual care | |

| No. | 303 | 157 |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 78.0 (73.0-84.0) | 78.0 (72.0-84.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 171 (56.4) | 85 (54.1) |

| Male | 132 (43.6) | 72 (45.9) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Asian | 19 (6.6) | 8 (5.3) |

| Black or African American | 8 (2.8) | 6 (4.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| White | 259 (89.9) | 135 (90.0) |

| ≥2 Race categories | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (6.9) | 10 (6.4) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 47 (15.6) | 22 (14.2) |

| 1 | 111 (36.9) | 55 (33.5) |

| ≥2 | 143 (47.5) | 78 (50.3) |

| Patient dementia severity—QDRS baseline, median (IQR) | 10.5 (6.0-15.5) | 10.5 (7.0-15.6) |

| ADI, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0-6.0) | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) |

| Metropolitanb | 257 (84.8) | 129 (82.2) |

| Caregiver characteristics | ||

| Caregiver age, median (IQR), y | 68.0 (59.0-75.0) | 65.0 (56.5-73.0) |

| Caregiver sex | ||

| Female | 204 (67.3) | 110 (70.1) |

| Male | 99 (32.7) | 47 (29.9) |

| Caregiver relationship | ||

| Spouse | 183 (60.4) | 88 (56.1) |

| Child | 100 (33.0) | 58 (36.9) |

| Other | 20 (6.6) | 11 (7.0) |

| Caregiver depressionc | ||

| None | 184 (60.7) | 95 (60.5) |

| Mild to severe | 119 (39.3) | 62 (39.5) |

| High caregiver burdend | 167 (55.1) | 85 (54.1) |

Abbreviations: ADI, Area Deprivation Index; QDRS, Quick Dementia Rating System.

Complete Medicare FFS coverage defined by a patient having Medicare Part A and Part B coverage continuously in the 12 months preceding and 12 months during trial enrollment and no Medicare Advantage (Part C) coverage.

Metropolitan defined as a rural-urban commuting area code of 1 to 3.

Measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 at baseline (none: <5; mild to severe: ≥5).

Measured with the 12-item Zarit Burden Interview at baseline (high burden: ≥17).

Total Cost of Care Outcome and Analysis

During the baseline period, patients randomized to the Care Ecosystem with 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage had a mean annual total cost of care of $11 401 ($10 785 after excluding outliers with a DFBETA value >2/√N) and median annual total cost of care of $4579 ($4540 after excluding outliers). Patients randomized to the usual care group had a mean annual total cost of care of $12 038 ($6390 after excluding outliers) and median annual total cost of care of $4284 ($3542 after excluding outliers) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Mean total cost of care varied monthly throughout the baseline and study periods, and the groups had similar baseline trends (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

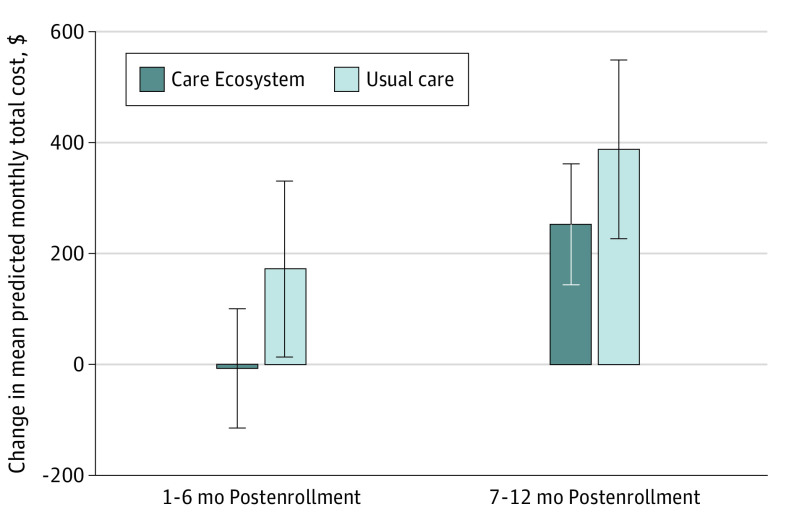

The adjusted effect of the Care Ecosystem on total cost of care was a reduction of $3290 from 1 to 6 months postenrollment, which met statistical significance (difference, −$3290; 95% CI, −$6149 to −$431; P = .02), and a reduction of $3027 from 7 months to 12 months postenrollment, which also reached statistical significance (difference, −$3027; 95% CI, −$5899 to −$154; P = .04) (Figure 2; eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Change Relative to Baseline in Mean Monthly Total Cost of Care Among Patients With 24-Month Continuous Medicare Fee-for-Service Coverage.

Predicted mean monthly total cost of care was found using the Stata margins postestimation command after performing the primary regression analysis with DFBETA outlier treatment. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Sensitivity analyses that repeated the primary analysis among patients with continuous Medicare FFS coverage adding those who died during any point in the trial (n = 484) and among patients with Medicare FFS or MA coverage who had nonmissing costs (n = 589) recapitulated these results (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Repeating the primary analysis among patients with 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage and excluding patients with outliers defined by trimming and winsorization thresholds at 97.5th and 99.5th percentiles also demonstrated similar cost reductions (eTable 5 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Performing a 2-stage hurdle analysis for patients with 24-month continuous Medicare FFS coverage including outliers yielded in stage 1 lower odds of having nonzero costs in the treatment group, which did not meet statistical significance (odds ratio, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.01-5.54). In stage 2, which was limited to the subset of patients with nonzero costs, it yielded an estimated reduction associated with the treatment of $1378 from 7 to 12 months postenrollment, which did not reach statistical significance (95% CI, −$4565 to $1809) and had wide confidence intervals that reflect incorporation of the more variable and right-skewed observations (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

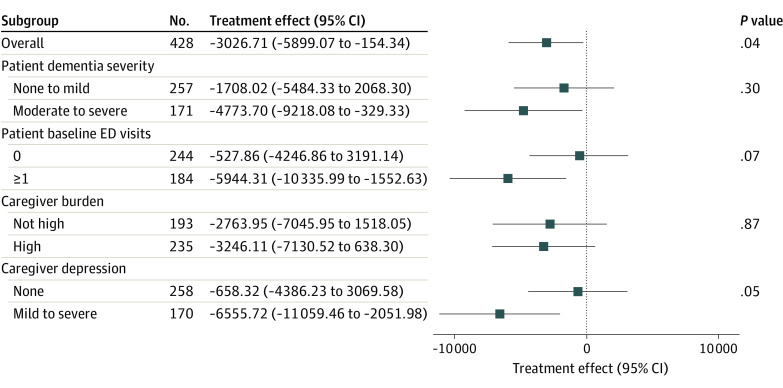

Heterogeneity of Treatment Effect

The benefit of the Care Ecosystem varied across baseline characteristics of the patient and caregiver (Figure 3). The data were consistent with expectations, suggesting greater reduction in total cost of care among patients with more severe dementia (moderate to severe dementia: −$4774; 95% CI, −$9218 to −$329), patients with higher use of the ED (1 or more ED encounters: −$5944; 95% CI, −$10 336 to −$1553), and caregivers with depression (PHQ-9 >5: −$6556; 95% CI, −$11 059 to −$2052) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care in Months 7 to 12 Postenrollment Among Patients With Dementia, Overall and Stratified by Patient and Caregiver Characteristics.

All models included a 3-way interaction term including the subgroup of interest, time period, and the intervention and excluded patients with a DFBETA value above 2/√N for either the 6- or 12-month Care Ecosystem effect. Models also adjusted for dementia severity as a continuous Quick Dementia Rating System score, except for the analysis that specifically examined the interaction between dementia severity and the Care Ecosystem treatment effect, in which case dementia severity was dichotomized and included in the 3-way interaction. ED indicates emergency department.

Discussion

In this prespecified secondary analysis, Care Ecosystem participation was associated with a large reduction in total Medicare spending. These findings are consistent with results of the Care Ecosystem trial that demonstrated significant treatment effects on patient outcomes (quality of life, ED visits, and potentially inappropriate medication use).2,19 Even though Care Ecosystem participants appeared to start at a higher level of total costs in the year before enrollment, their costs quickly stabilized by 6 months and they maintained a significant treatment effect on costs out to 12 months. Results were robust to various methods of outlier adjustment and when including participants who died during the trial or had incomplete data due to MA coverage or incomplete FFS coverage. The estimated reduction in mean monthly total cost of care was $526 after adjustment for dementia severity and allowing for time-specific treatment effects. Based on the upper bound of estimated monthly program costs, which range from $86 to $105 per month, the observed savings are far in excess of program costs.30 There were trends for greater benefit of the Care Ecosystem among patients who had higher baseline use of the ED and caregivers with depression, which suggests that these variables may be useful for determining who would be expected to derive the greatest economic benefit from participation in a collaborative dementia care program such as the Care Ecosystem.

Our findings extend the validity of prior results by studying a collaborative dementia care program in the context of a large randomized clinical trial.3,9 Other studies have demonstrated that these team-based, patient- and caregiver-centered models improve quality of life and well-being for patients with dementia and their caregivers across multiple different settings and patient populations2,7,12,31 and lead to a reduction in ED visits.2 A few programs have examined their effect on cost of care and reported cost reductions that range from no cost reduction to cost reductions of $200 to $447 per month.15,16,32,33 Our findings confirm cost savings shown in previous work and demonstrate that cost savings can be considerably larger than previously estimated.

Additionally, while the benefit of Care Ecosystem participation was high for many patients, treatment effects varied substantially. Reductions in total cost of care appeared to be highest for the 40% of patients with moderate to severe dementia, the 43% of patients with at least 1 ED encounter, and the 40% of patients with caregivers who had symptoms of depression in the 12 months preceding enrollment. These results emphasize that Medicare cost savings can be expected to differ across patient and caregiver populations—information that should be integral to new payment models that reimburse for the Care Ecosystem and other collaborative care programs and to the prioritization of patients for the care when resources are limited.

These findings have important implications for health care delivery models and payment for the growing population with dementia. There are over 20 health systems that have implemented the Care Ecosystem model nationally, reinforcing the need for programs that focus on providing caregiver support and offering additional information about the effectiveness of these models in different health settings.34 Importantly, these program costs are borne by the health system while the cost savings are realized by Medicare, which underscores the importance of advancing value-based care arrangements that align the incentives of payers and health care systems, or adequately covering program costs via new payment models.18 On July 31, 2023, Medicare introduced the Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model35 that will provide a monthly per-beneficiary payment to support collaborative dementia care for patients with Medicare FFS and their caregivers.

Limitations

There are important limitations to this analysis. First, a large proportion of patients were covered under MA plans and had missing data related to utilization and costs. They were excluded from the primary analysis to avoid bias from mismeasurement of our outcomes. This inevitably led to a smaller sample size and lower statistical power to study heterogeneity of the treatment effect by patient and caregiver characteristics and may have limited generalizability to patients without Medicare FFS (eg, MA). Second, generalizability to a more diverse, less privileged population is limited because the initial trial enrolled patients who were predominantly White and had low annual health care costs. Furthermore, the program was delivered from academic medical centers. However, our results suggest that the benefit of the Care Ecosystem may be even larger among more vulnerable populations who otherwise lack consistent access to adequate caregiver support and health care resources. Third, the analysis focused on Medicare reimbursements for formal health care costs and did not include information about beneficiary payments and informal health care costs. Fourth, because those randomized to the Care Ecosystem had higher total cost of care at baseline, the decrease in cost of care during the trial could represent a regression to the mean as opposed to a true treatment effect. Nevertheless, the baseline trend in total cost of care was similar in the 2 groups during the 12 months preceding trial enrollment, and baseline differences in total cost of care were addressed by incorporating a random effect for the dyad across time in our regression model. Furthermore, participants in the Care Ecosystem group showed cost stabilization that was maintained throughout the intervention period.

Conclusions

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial, we found that the Care Ecosystem collaborative care model for patients with dementia reduced Medicare costs, exceeding previously estimated program costs.30 Savings were greatest for vulnerable dyads, including those dealing with higher use of ED resources and caregiver depression. These results can inform payment models that align incentives between payers and clinicians and that are attractive enough for health systems to invest in dementia care reform. Future work is needed to address barriers to broad dissemination and diffusion and to evaluate the Care Ecosystem’s effectiveness in a larger and more diverse population.

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Distribution of Total Cost of Care Among Patients With 24-Month continuous Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Coverage

eFigure 2. Mean Monthly Total Cost of Care Among Patients With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage

eTable 1. Proportion of Participants With Missing Medicare Reimbursement Data, Stratified by Completeness of Fee-for-Service (FFS) Coverage

eTable 2. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Patients With Complete 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS and Patients With Incomplete 24-Month Medicare FFS by Intervention Group

eTable 3. Total Cost of Care in the 12-Months Preceding and 12-Months During Enrollment Among Patients With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage

eTable 4. Heterogeneity of the Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 1-6 Months and 7-12 Months After Trial Enrollment

eTable 5. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment With Outliers Trimmed at 97.5th to 99.5th Percentile

eTable 6. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment With Winsorization at 97.5th to 99.5th Percentile

eTable 7. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment Modeled Among Enrollees With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage Using a Hurdle Model

eTable 8. Community Resources and Other Topic Areas That Care Team Navigators Discussed With Caregivers

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al. US health care spending by payer and health condition, 1996-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(9):863-884. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, et al. Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the Care Ecosystem randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1658-1667. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living With Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. National Academies Press; 2021. doi: 10.17226/26026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Messina FC, Miller DK, Callahan CM. Emergency department use among older adults with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30(1):35-40. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165-172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyketsos CG. Prevention of unnecessary hospitalization for patients with dementia: the role of ambulatory care. JAMA. 2012;307(2):197-198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings LA, Hollands S, Keeler E, Wenger NS, Reuben DB. The effects of dementia care co-management on acute care, hospice, and long-term care utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2500-2507. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guterman EL, Allen IE, Josephson SA, et al. Association between caregiver depression and emergency department use among patients with dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1166-1173. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heintz H, Monette P, Epstein-Lubow G, Smith L, Rowlett S, Forester BP. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(3):320-330. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Possin KL, Merrilees J, Bonasera SJ, et al. Development of an adaptive, personalized, and scalable dementia care program: early findings from the Care Ecosystem. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuben DB, Gill TM, Stevens A, et al. D-CARE: the dementia care study: design of a pragmatic trial of the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of health system-based versus community-based dementia care versus usual dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2492-2499. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148-2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713-726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, et al. A controlled trial of Partners in Dementia Care: veteran outcomes after six and twelve months. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(1):9. doi: 10.1186/alzrt242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings LA, Laffan AM, Schlissel AC, et al. Health care utilization and cost outcomes of a comprehensive dementia care program for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):161-166. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marek KD, Stetzer F, Adams SJ, Bub LD, Schlidt A, Colorafi KJ. Cost analysis of a home-based nurse care coordination program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2369-2376. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalowsky B, Xie F, Eichler T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative dementia care management—results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(10):1296-1308. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawyer RJ, LaRoche A, Sharma S, Pereira-Osorio C. Making the business case for value-based dementia care. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2023;4(3). doi: 10.1056/CAT.22.0304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu AK, Possin KL, Cook KM, et al. Effect of collaborative dementia care on potentially inappropriate medication use: outcomes from the Care Ecosystem randomized clinical trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(5):1865-1875. doi: 10.1002/alz.12808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galvin JE. The Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS): a rapid dementia staging tool. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015;1(2):249-259. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—the Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2456-2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . 2010 Rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes. Accessed July 15, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/documentation/

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345-359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hébert R, Bravo G, Préville M. Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging. 2000;19:494-507. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800012484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652-657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulcahy AW, Sorbero ME, Mahmud A, et al. Measuring Health Care Utilization in Medicare Advantage Encounter Data: Methods, Estimates, and Considerations for Research. RAND Corporation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O’Hagan A, Thompson SG. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2011;20(8):897-916. doi: 10.1002/hec.1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weichle T, Hynes DM, Durazo-Arvizu R, Tarlov E, Zhang Q. Impact of alternative approaches to assess outlying and influential observations on health care costs. Springerplus. 2013;2:614. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosa TD, Possin KL, Bernstein A, et al. Variations in costs of a collaborative care model for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(12):2628-2633. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reuben DB, Tan ZS, Romero T, Wenger NS, Keeler E, Jennings LA. Patient and caregiver benefit from a comprehensive dementia care program: 1-year results from the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(11):2267-2273. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan RO, Bass DM, Judge KS, et al. A break-even analysis for dementia care collaboration: Partners in Dementia Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):804-809. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3205-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French DD, LaMantia MA, Livin LR, Herceg D, Alder CA, Boustani MA. Healthy Aging Brain Center improved care coordination and produced net savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):613-618. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.University of California San Francisco . Care Ecosystem. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://memory.ucsf.edu/research-trials/professional/care-ecosystem

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/guide

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Distribution of Total Cost of Care Among Patients With 24-Month continuous Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Coverage

eFigure 2. Mean Monthly Total Cost of Care Among Patients With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage

eTable 1. Proportion of Participants With Missing Medicare Reimbursement Data, Stratified by Completeness of Fee-for-Service (FFS) Coverage

eTable 2. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Patients With Complete 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS and Patients With Incomplete 24-Month Medicare FFS by Intervention Group

eTable 3. Total Cost of Care in the 12-Months Preceding and 12-Months During Enrollment Among Patients With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage

eTable 4. Heterogeneity of the Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 1-6 Months and 7-12 Months After Trial Enrollment

eTable 5. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment With Outliers Trimmed at 97.5th to 99.5th Percentile

eTable 6. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment With Winsorization at 97.5th to 99.5th Percentile

eTable 7. Effect of the Care Ecosystem on Total Cost of Care From 7 to 12 Months After Enrollment Modeled Among Enrollees With 24-Month Continuous Medicare FFS Coverage Using a Hurdle Model

eTable 8. Community Resources and Other Topic Areas That Care Team Navigators Discussed With Caregivers

Data Sharing Statement