Abstract

Pericytes are mesenchymal-derived mural cells localized within the basement membrane of pulmonary and systemic capillaries. Besides structural support, pericytes control vascular tone, produce extracellular matrix components, and cytokines responsible for promoting vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. However, pericytes can also contribute to vascular pathology through the production of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines, differentiation into myofibroblast-like cells, destruction of the extracellular matrix, and dissociation from the vessel wall. In the lung, pericytes are responsible for maintaining the integrity of the alveolar-capillary membrane and coordinating vascular repair in response to injury. Loss of pericyte communication with alveolar capillaries and a switch to a pro-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic phenotype are common features of lung disorders associated with vascular remodeling, inflammation, and fibrosis. In this article, we will address how to differentiate pericytes from other cells, discuss the molecular mechanisms that regulate the interactions of pericytes and endothelial cells in the pulmonary circulation, and the experimental tools currently used to study pericyte biology both in vivo and in vitro. We will also discuss evidence that links pericytes to the pathogenesis of clinically relevant lung disorders such as pulmonary hypertension, idiopathic lung fibrosis, sepsis, and SARS-COVID. Future studies dissecting the complex interactions of pericytes with other pulmonary cell populations will likely reveal critical insights into the origin of pulmonary diseases and offer opportunities to develop novel therapeutics to treat patients afflicted with these devastating disorders. © 2021 American Physiological Society. Compr Physiol 11:2227–2247, 2021.

Introduction

The lung comprises a diverse population of unique cells that carry out a wide range of tasks such as immune surveillance, gas exchange, detoxification, and repair. A recent single-cell RNA sequencing atlas of the human lung has led to identifying 58 unique cell populations, the most abundant being capillary endothelial cells (ECs approximately 23% of all lung cells) (170). Capillary ECs are a significant component of the alveolar-capillary membrane, a thin tissue barrier responsible for gas exchange between alveolar air and the pulmonary circulation (66). Capillaries are composed of mural cells that provide support and regulate perfusion through vascular tone control. Among the mural cells, pericytes cover the largest capillary surface area beginning at the precapillary arterioles and reaching as far as the postcapillary venules (Figure 1). In addition to vasoregulation, pericytes are involved in the synthesis of the capillary basement membrane, establishment of the endothelial barrier, immune surveillance, and the production of angiomodulatory cytokines that support EC homeostasis and metabolic activity (47, 49, 50, 53, 64). Thus, it is no surprise that many lung disorders that feature disruption of alveolar-capillary membrane integrity are characterized by disruption of endothelial-pericyte communications and loss of capillary integrity.

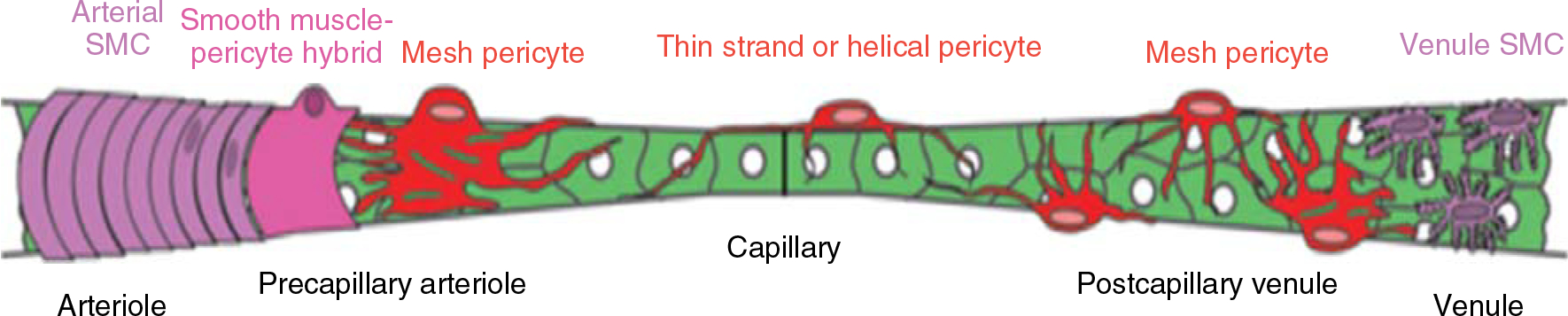

Figure 1.

Distribution of pericytes across the length of the capillary wall. Note that the morphology of the pericyte can be variable depending on whether the pericyte is located close to the precapillary arteriole, the capillary body, or the postcapillary venule. Reused, with permission, from Hartmann DA, et al., 2015 (68), Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

A significant challenge for studying lung pericyte pathobiology in the lung is the lack of a consensus definition that helps distinguish pericytes from other mural cell populations. With the advent of new genetic technologies and imaging tools, there has been a resurgence in properly studying how pericytes contribute to the pathobiology of lung diseases. This article will touch upon the current approach to identify pericytes using imaging and molecular markers and will introduce currently available tools to study lung pericyte biology in vitro and in vivo. We will also discuss available evidence that supports the contribution of pericytes to the pathobiology of acute and chronic pulmonary disorders. We conclude by speculating how our knowledge will likely continue to evolve as our capacity to study these elusive cells improves with advances in cell phenotyping technologies and genetic methods.

Lung Pericytes: A Historical Perspective

Pericytes were first described in 1873 by C. Rouget as highly ramified adventitial cells located on the surface of capillaries with a notable “bump-on-a-log” morphology that set them apart from other vascular cells (73). Zimmerman (1923) was the first to coin the term “pericyte” to describe mural cells emerging from the arteriolar end of the capillary bed, then assuming a highly ramified morphology as they stretched across the capillaries and a stellate morphology at the venule end of capillaries (8). The proximity of pericytes to arterioles led Zimmerman to speculate whether pericytes represented a transitional form of the smooth muscle cell (SMC) uniquely adapted to serve the capillary circulation. This early observation concerning the different morphological types of pericytes and their similarities with SMCs is still relevant today as we try to reach a consensus definition of pericytes.

Following his first report, Zimmerman carried out systematic studies that documented pericytes’ existence in the microcirculation of multiple species (mammals, amphibians, fish, etc.). In mammals, Zimmerman demonstrated that pericytes are present in the capillaries of almost every major organ except one: the lung. For the next 50 years, lung pericytes’ search proved to be frustrating, forcing various experts to speculate that pericytes did not exist in the lung. However, the electron microscopy (EM) availability in the 1960s led to a pericyte renaissance, as detailed ultrastructural studies of vascular tissues gave researchers greater insight into how pericytes interact with the adjacent endothelium. EM images demonstrate that pericytes are closely apposed to ECs but separated by a basement membrane that ensheaths the pericyte body and the branching cell processes that envelop the capillary surface. Ensheathment of the pericyte within the basement membrane is a key anatomical feature that helps separate pericytes from other mural cells (fibroblasts, SMCs) located outside the basement membrane. Higher-definition images show that pericyte processes extend beneath the capillary basement membrane to contact the EC membrane directly. Another exciting feature of pericytes is that their cytoplasm shows a dense meshwork of fine cytoplasmic filaments. In contrast, closer to the plasma membrane, there is a high index of pinocytotic vesicles and lysosomal vesicles. Confirmation of lung pericytes’ existence finally came in 1974 when Ewald R. Weibel conducted a systematic EM assessment of human lungs and found definite proof that pericytes were indeed a component of the alveolar microcirculation (185) (Figure 2). When comparing pericyte distribution in lung versus systemic circulation, Weibel writes:

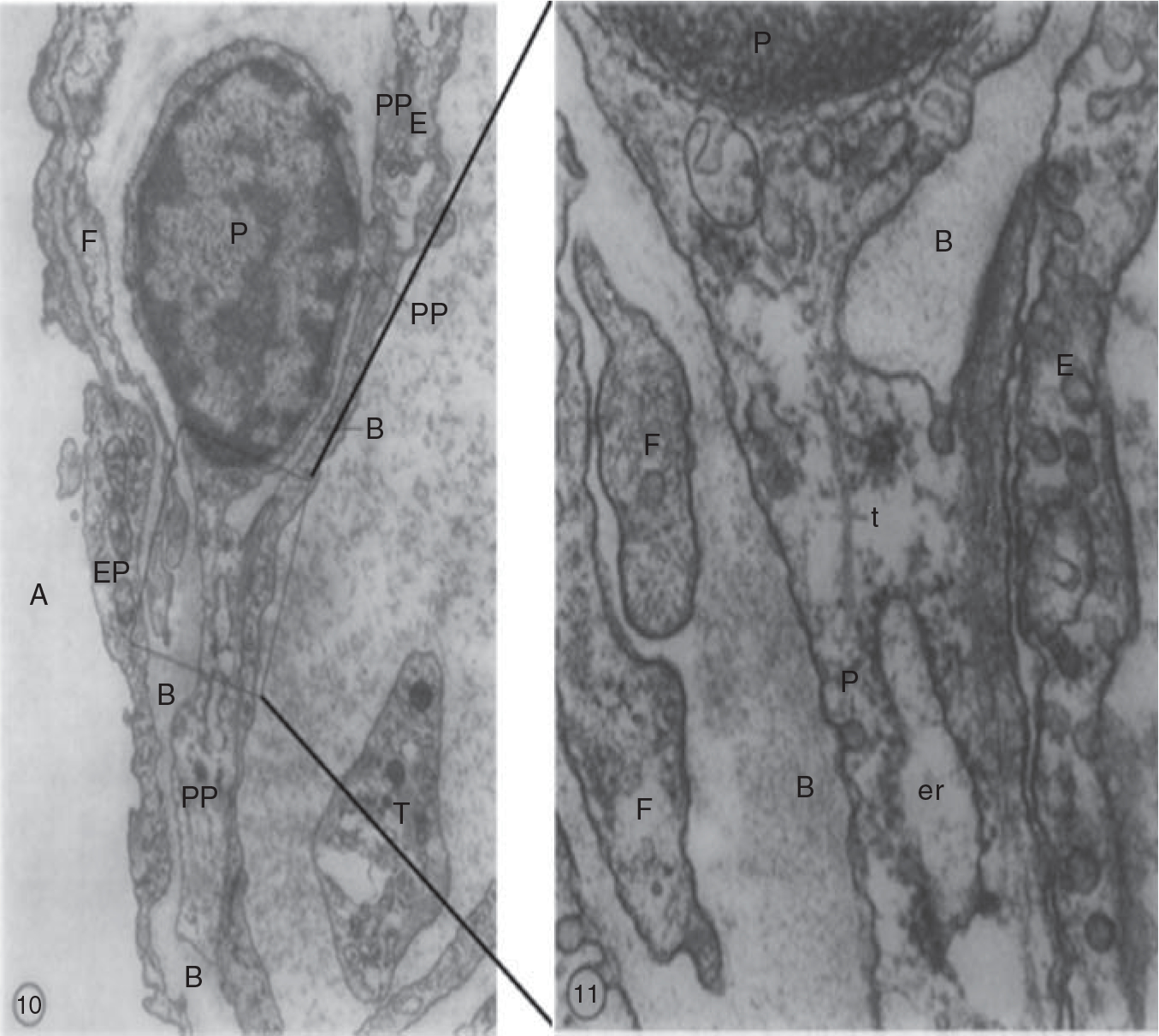

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy images of the human lung illustrate the intimate association between pericytes and endothelial cells in human lung capillaries. The pericytes are located within the basement membrane and extend long thin processes that establish contacts with the adjacent endothelial cell. Right panel is a higher magnification image of the area within the square. PP, pericyte processes; B, basement membrane; F, cytoplasmic filaments; E, endothelium; P, pericyte; A, alveolus.

Whereas it is very easy to find pericytes in cardiac muscle or pancreas capillaries, for example, one must search for them in the lung. The relatively rare small processes observed also suggest that the cytoplasmic branches must be quite loosely arranged around the capillary, whereas in systemic capillaries they may form a dense girdle. (185)

Once the existence of pericytes in the pulmonary microcirculation was confirmed, it was not long before reports of possible association with pulmonary vascular diseases began to appear. Pericytes were first suggested as not an extension of muscle along a pathway but as a cell type that differentiated to form new muscle as early as the second day of hypoxia in rat pulmonary arterial circulation (109). This groundbreaking study led to reveal a similar human pericyte pathological role in children with congenital heart defects for the first time, which further suggested pericytes at the nonmuscularized regions of peripheral arteries contributed to new muscle formation under pathological conditions (110).

Developmental Origin of Pericytes

The developmental origin of pericytes is difficult to trace to one ancestor and is likely to differ between tissues. Available evidence suggests that lung pericytes’ origin can be traced to mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (7, 127). MSCs are multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into various cell types such as adipocytes, SMCs, and osteoblasts. MSCs predominantly originate in the mesothelium, the single-layer squamous epithelium that gives rise to the lung, liver, and heart (147, 178). While human lung pericytes’ origin has not been definitively established, murine fate-mapping studies have shown that lung pericytes arise from MSCs following their migration to the developing lung during embryogenesis (127). Besides pericytes, MSCs also give rise to other mural cell types such as SMCs and fibroblasts or can remain as resident mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to support tissue maintenance and homeostasis (7, 39, 111, 187, 202).

Besides their role as mural cells, pericytes can act as progenitor cells and transdifferentiate into other mesenchymal cell types in response to injury and disease (18, 19, 139–141, 180). Crisan and colleagues showed that cultured pericytes from various tissues express MSC markers CD10, CD13, CD44, and could differentiate into other cell types when exposed to conditioned media (33). Our group and others have shown that lung pericytes can assume a smooth muscle-like phenotype and contribute to distal vessel muscularization in response to chronic hypoxia (22, 129). In the murine model of lung fibrosis, fate mapping has shown that pericytes detach from vessel walls and migrate to the interstitial space where they differentiate into myofibroblast-like cells and contribute to parenchymal fibrosis (183, 184). While many investigators have enthusiastically embraced the idea that MSC and pericytes could serve as the basis for cell-based therapeutics in chronic lung diseases, it is important to recognize that tracing the cell origin to the pericyte is complicated by the lack of unique pericyte markers and the difficulty of distinguishing pericytes from other cell populations such as MSCs (52, 127).

Experimental Approaches to Study Pericytes: In Vitro and In Vivo Models

Approach to pericyte identification

EM studies of ultrathin lung sections have shown that pericytes are located within the basement membrane of alveolar capillaries, have small cell bodies and stellate shapes with long thin branches that wrap around the vessel circumference and form direct “Peg-socket” contacts with ECs (as high as >1000 contacts per EC) through adhesion plaques and gap junction-like structures (185). Technological advances in confocal microscopy, image processing, multi-colored fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and lineage tracing have given us unprecedented access to study pericytes and their interaction with other cells in the lung circulation. However, it is essential to recognize that no single cell marker can distinguish pericytes from different cell types. Thus, the approach to identify pericytes in lung sections rely on the use of at least two cell markers (Table 1), counter-labeling of ECs, morphology (pericytes have small cell bodies, multiple long thin branches wrapped around vessels), and location in small (<30um) pulmonary arteries, capillaries, and venules (7, 195–197).

Table 1.

Established Pericyte Markers

| Marker | Expression location | Function |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| a-SMA (Alpha-smooth muscle actin) | Cytosolic marker; commonly expressed throughout arterioles, venules, pre- and postcapillaries | Aides in the relaxation and contraction of arteries and veins thereby regulating the blood flow |

| NG2/CSPG4 (Neuron glial antigen-2/Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4) | Membrane-bound marker; found on arteriolar, capillary, and venular pericytes. Lost in postcapillary venules | Required for pericytes to interact with endothelial cells during tumor blood vessel formation |

| Platelet-derived growth factor-B (PDGFR-B) | Membrane-bound marker; found commonly on brain pericytes on arterioles, capillaries, and venules | Recruits pericytes during de novo blood vessel formation |

| Regulator of G protein signaling 5 (RGS5) | Common cytosolic marker in brain pericytes coating arteries, venules, and capillaries. Presented on developing pericytes free from PDGF-β signaling | Tumor and embryonic angiogenesis |

| LEPR (Leptin Receptor) | Found on pericytes located in bone marrow and on perisinusoidal cells | The positive cells are sources for stem cell factors and have a proliferative environment |

| Nestin | Bone marrow pericyte marker. Found on pericytes on arterioles, capillaries, and venules. High NG2+ periarteriolar and low LepR+ perisinusoidal populations | HSC quiescence and HSC cycling regulated by periarteriolar and sinusoidal subpopulations |

| FOXD1+ progeny (Forkhead box D1) | Found on pericytes and fibroblasts of the lung and kidneys | Contributes in the progression of kidney and pulmonary fibrosis |

| Gli1+ progeny (Glioma-associated oncogene) | Expressed by perivascular mesenchymal stem cell-like cells in multiple organs | Contributes to the myofibroblast population in the kidneys, lungs, liver, and heart |

| ADAM12+ progeny (ADisintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 12) | Located on mesenchymal perivascular cells, and found in pericytes within the adult skeletal muscle and skin | Cells with pro-fibrotic fates contributing to fibrosis |

| 3G5/RBS14 (3-ganglioside-5 antigen/Ribosomal binding site-14) | Membrane-bound marker located on microvascular pericytes; expressed in the renal cortex, corneal keratocytes, and pericytes of human skin | Respond to external stimuli commonly associated with wound repair; most cells expressing 3G5 in capillaries do not present a-SMA making it a valuable pericyte marker |

| NOTCH3 (Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3) | Located on the membrane of brain pericytes | Responsible for maintaining blood-brain barrier function, pericyte proliferation, and overall brain vascular integrity through endothelial/pericyte interactions |

| Desmin | Cytoskeletal protein mainly distinguishes young pericytes | Clustered intermediate filament responsible for maintain shape and structure of pericyte, contributing to vessel stabilization |

| TBX18 (T-box transcription factor 18) | Membrane-bound proteins on pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, and other interstitial cell types | Conserved protein with vital roles during embryogenesis specifically in epicardial development |

Isolation of pericytes from lung tissue

A major asset to the study of pericytes in vitro is the capacity to purify pericytes from human lung tissue. The standard markers used for isolation include 3G5, NG2, α-SMA, desmin, and PDGFR-β. However, it is essential to point out that surface marker expression can vary depending on the species, organ, and disease state (160). Across different organs, pericytes display specialized functions and also differ in specific markers: the combination of markers used to identify pericytes in the lung may not be best applicable to identifying pericytes, for instance,in the kidney. For example,NG2 and α-SMA are predominantly expressed in pericytes located within precapillary arterioles and postcapillary venules, whereas their expression is lower in capillary pericytes (47). Furthermore, NG2 expression is absent in the venular pericytes of rat mesenteric and subcutaneous tissue and skeletal muscle but may be induced during angiogenesis and vascular remodeling. Use of FACS can help purify specific pericyte subpopulations from cell suspensions through negative selection against other cells commonly found in tissue such as ECs, hematopoietic cells, and myogenic cells (32).

To purify pericytes from lung tissue, we and others have employed a column-based cell isolation technique using magnetic beads coated with IgM monoclonal antibodies against 3G5, a surface ganglioside expressed by pericytes (6, 41). Pericytes in culture display a star-shaped morphology characterized by long cytoplasmic processes and prominent intracellular actin bundles. In our hands, primary lung pericyte cultures can be propagated for up to ten passages while maintaining their morphology and consistent expression of surface markers (e.g., NG2, 3G5, PDGFRβ) before the cells reach a state of senescence. Similar to SMCs and fibroblasts, pericytes in culture can grow on top of each other. Still, their appearance is very different from that of ECs (cobble-like), fibroblasts (two ends long spindle-shaped with extended filopodia), and SMCs (fusiform and compact). These pericytes can be used in a wide variety of 2-D or 3-D cell-based assays and can be studied either in monoculture or in co-culture with ECs. We advise readers to consult these excellent reviews (118, 152).

In vivo lineage tracing of pericytes

The use of lineage tracing has dramatically facilitated our capacity to identify and track lung pericytes in vivo. The lineage tracing principle is based on a Cre/lox system that combines an inducible Cre recombinase with a fluorescence reporter to label a target cell population permanently. When linked to the promoter for a pericyte marker (e.g., NG2, PDGFRβ), Cre recombinase is expressed and triggers a fluorescence reporter (e.g., GFP, TdTomato) that labels pericytes and their progeny. The advantage of the Cre-Lox system stems from its ability to not only label cells but also study the functions of candidate genes in specific cells and tissues (201). In the following sections, we discuss the two most commonly used lineage tracing models in pericyte studies and address some of the limitations inherent to using in vivo lineage tracing to study lung pericyte biology. A summary of other available mouse models can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Murine Models Used in Pericyte Lineage Tracing

| Promoter | Insert | Type | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PDGFRβ | Cre | Transgenic | During early development, PDGRb-Cre labels multiple cellular lineages in addition to pericytes (61) |

| PDGRb (BAC) | CreERT2 | Transgenic, tamoxifen inducible | Pulmonary pericytes coexpress NG2 and Notch 3 (88) |

| NG2 | CreER BAC | Transgenic, tamoxifen inducible | NG2+ cells are Pdgfrb+ and aSMA (34, 131) |

| NG2 | Ds-Red BAC | Transgenic | NG2+ cells are CD 146+, NOTCH3+, PDGFRβ+. Increase in pulmonary pericyte expressing α SM actin is observed at Day 14 (2, 88) |

| FoxD1 | GFP-Cre | Knock-in | Foxd1 progenitor-derived cells are PDGFRβ+, NG2+, αSMA−, Aquaporin V−, CD31−, CD45−. 15% to 20% express collagen I. A small population is PDGFRα+ (77) |

| FoxD1 | Cre-ER | Knock-in, tamoxifen inducible | Foxd1 promoter is active from E11.5 and E12.5 and downregulated by E15.5 (77) |

| FoxJ1 | CreERT2 | Transgenic, tamoxifen inducible | Cells are NG2+ and αSMA− (131) |

| Tbx18 | CreERT2 | Knock-in, tamoxifen inducible | In larger arterioles and arteries, Tbx18-GFP+ cells are αSMA+. Interstitial Tbx18-expressing cells of brain, retina, cardiac ventricles, skeletal muscles, and fat depots as NG2+, CD146+, Cd31−, CD34−, CD45− Cd117−, Sca1−, CD29+, CD140b+, CD 146+, NG2+ (61) |

| PDGFRβ | P2A-CreERT2 | Knock-in, tamoxifen inducible | Labeled NG2+, desmin+, PDGFRP+ perivascular cells in the retina and the brain (35) |

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRβ-CreERT2)

PDGFRβ is a widely expressed marker on pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs). The PDGFRβ signaling pathway is implicated in pericyte proliferation, migration, and recruitment during angiogenesis. Cre recombinase driven by the PDGFRβ promoter is crossed with a mouse reporter strain to label perivascular cells in vivo. During embryonic development, PDGFRβ is expressed throughout the embryo and is unsuitable for pericytes’ specific labeling (61). PDGFRβ expression is confined to pericytes and vSMCs in adult mice, making inducible PDGFRβ-Cre models more suitable by tamoxifen injection. An inducible PDGFRβ-CreERT2 model was used to label pericytes in the retina using tamoxifen injections over different time frames to investigate the importance of pericyte recruitment in retinal vessels for the formation and maturation of the retinal blood barrier (123). Another inducible model, PDGFRβ-P2A-CreERT2, was used to label 84.17±3.48% of NG2+/PDGFRβ+ PCs to investigate the angiogenic retina and brain at different points after tamoxifen injection (35). In the lung, a tamoxifen-inducible PDGFRβ-Cre model allowed for the labeling of pericytes tightly associated with ECs following tamoxifen administration 1 to 3 days after birth (88). A cross between PDGFRβ-CreER mice and mice with loxP-flanked Yap1 and Wwtr1 (encoding the TAZ protein) alleles generated mice with inducible pericyte-specific disruptions in YAP1 and TAZ signaling that altered postnatal lung morphogenesis (88). Pericyte-deficient mouse lines have also been established to investigate pericyte degeneration. PDGFRβ-null mice die perinatally by microvascular hemorrhaging and edema formation. They display reduced pericyte coverage, brain endothelial hyperplasia, dilated hyperpermeable capillaries, and microaneurysms during embryonic development (71). Mouse models with altered PDGFRβ activity can also be used to study the effects of pericyte depletion (75). The most common models include PDGFRβ ret/ret mice (where PDGF-β retention motif is depleted to disrupt its binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans), and PDGFRβ +/− or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) hypomorph mice, which have a 20% to 50% reduction of pericytes (30). Adult mouse models with pericyte depletion have been shown to have impaired blood-brain barrier (BBB) functionality (75). Interestingly, a study using NG2-Cre-PDGFRß flox mice, with inducible knockout by tamoxifen injection, showed that the knockout of PDGFRβ in pericytes leads to a reduction in angiogenesis and vessel growth in the retina model.

NG2-CreERT2

NG2 proteoglycan is a marker expressed on pericytes and is implicated in pericyte proliferation, motility, angiogenesis, and endothelial-pericyte crosstalk (157). Traditionally, NG2-based mouse models have been used in research involving oligodendroglial cell lineages and myelin, but have recently expanded to include pericyte studies. The first study implicating NG2 in pericyte biology resulted from the observation that the retina of NG2 null mice had a loss of pericyte coverage (157). Various inducible and noninducible NG2-Cre reporter mouse models and NG2-dsRed mice models have been used to image pericytes in the retina and study cerebral blood flow (63, 157). In the lung, NG2-dsRed models have been used to identify pericyte subpopulations and evaluate their response to tissue injury (17). NG2DsRedBAC-transgenic reporter mice were used to study pericyte structure and coverage in pulmonary arteries, discovering that pulmonary vascular remodeling is accompanied by an increase in pericyte density and coverage in distal pulmonary arteries in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (129). Our lab has optimized the reporter label efficiency using the NG2-Cre-ER/ROSA-tdT fl/+ mouse model. Our published data suggest that pericytes may gain an SMC-like phenotype through autocrine SDF1-CXCR4 signaling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (195). Cre/lox technology can also produce mice in which NG2 is ablated in pericytes by crossing PDGFRβ-Cre mice with NG2 floxed mice. These mice have specific deficits in tumor vascularization, including decreased pericyte coverage of ECs, diminished assembly of the vascular basement membrane, reduced vessel patency, and increased vessel leakiness (157).

Drawbacks of in vivo lineage tracing models

Although in vivo animal models are useful for studying lung pericytes, there are limitations inherent to using Cre/Lox animal models in general that are important to recognize when using these models to study pericyte biology. Cre recombinase is commonly used to target genes expressed in specific cells in adult mice (155). Depending on the mouse’s developmental stage, Cre recombinase’s expression may not be limited to a particular number of cells, and there may be an unexpected transient expression. Also, there have been many reports of the discrepancies between the labeling efficiency of different mouse models. The labeling efficiency can be affected by the promoter’s activity, location, accessibility of the target loxP sites, and experimental conditions for inducible models. In one experiment, postnatal tamoxifen administration labeled only approximately 15% of the NG2+ lung cells in NG2-CreER mice (131).

Furthermore, discrepancies between the recombination efficiency may arise when breeding with different reporter lines. A significantly reduced labeling of NG2+ pericytes was detected when PDGFRβ-P2A-CreERT2 was crossed with the reporter line Rosa-mT/mG, suggesting that the mouse reporter’s selection lines should be done carefully (35). Also, the lack of a pericyte-specific marker means that working with pericytes is complicated and subject to uncertainty. The identification of pericytes, whether in vivo or in vitro, indicates the need for multiple criteria, including location, morphology, and protein expression. This makes it increasingly hard to refine methods to identify and isolate lung pericytes, as different pericyte populations express various overlaps of markers and markers common to other mural cells (including vSMCs). Pericyte density is also different among organs, with the highest ratio in the retina and brain, and the lowest in the muscle (200). Finally, there are differences in pericyte identification across animal and human models. For example, mouse lung pericytes have a higher expression of CD146 as compared to PDGFRβ+ human lung pericytes (78). We advise that findings using in vivo models should be validated in human tissue using the tools described above (20). Future applications of technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing to delineate pericyte subpopulations are promising and will hopefully lead to a better understanding of pericyte identity in the lung.

Molecular Basis of Endothelial-Pericyte Interactions in the Vasculature

The capillary is made of a thin layer of ECs, which are the primary physical barrier between blood and alveolar tissue. Pericytes are ubiquitously present in the blood micro-vessels, predominantly in capillaries. The perivascular cells interact with ECs via direct cell-cell contact, changes in the extracellular matrix, or release of various growth factors. Pericytes not only play a significant role in the maintenance of vascular structure during vessel maturation but also prevent the excessive migration and proliferation of ECs, as seen in various vascular diseases, including pulmonary hypertension. On the other hand, during the process of angiogenesis, formation of new blood vessels is initiated by the detachment of pericytes from the site through regulation by various signaling molecules such as PDGF, transforming growth factor (TGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Angiopoeitin/Tie2, Wnt, Notch along with ECM remodeling through modulation by MMPs, and other ECM proteins (Figure 3) (4, 7, 12, 17, 196). Once the vessel is formed, pericytes are recruited to stabilize the blood vessel. Perivascular cells surrounding the blood vessel have an anti-angiogenic effect orchestrated through signaling molecules’ regulation. Here, we discuss various signaling molecules that maintain the endothelial-pericyte balance and stabilize the vasculature structure. Table 3 summarizes the key players in endothelial-pericyte communications discussed in detail in the following sections.

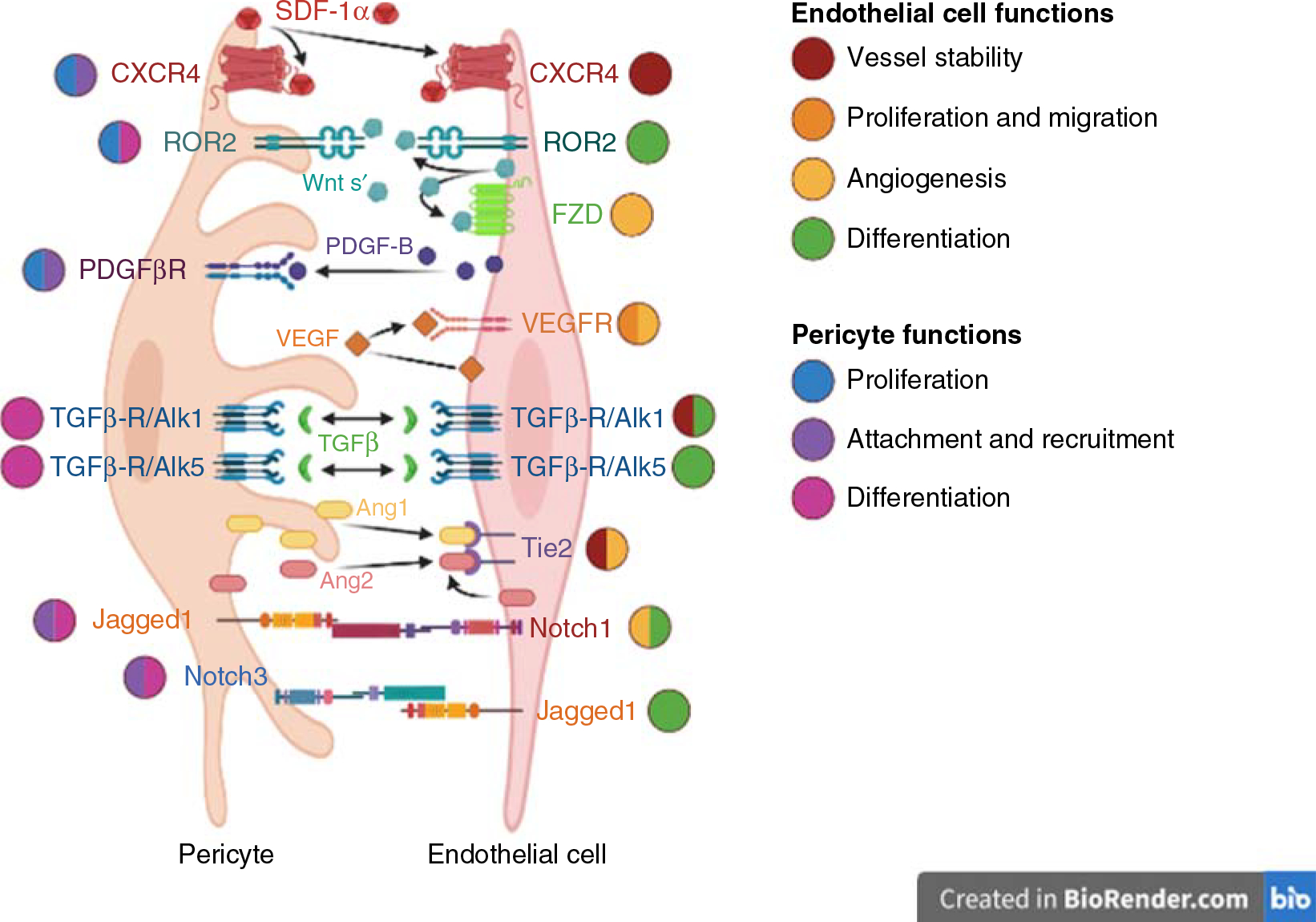

Figure 3.

Signaling pathways that regulate crosstalk between endothelial cells and pericytes in the vasculature. These events are critical for the establishment of functional vessels and disruption of one or more pathways can result in vascular dysfunction and inappropriate angiogenesis.

Table 3.

Key Players in Endothelial-Pericyte Communications

| Ligand | Receptor | Function | Cellular location |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Receptor | |||

|

| ||||

| PDGF-β | PDGFβ-R | Synthesis of angiogenic peptides, cell proliferation, and chemotaxis (77, 194) | Endothelial cells | Pericytes |

| Prevents pericyte detachment and aberrant angiogenesis (56) | ||||

| TGFβ | ALK1 | Endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis (16) | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Endothelial cells, pericytes |

| ALK5 | Endothelial apoptosis and quiescence | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Endothelial cells, pericytes | |

| Mesenchymal cell differentiation (7, 8, 77, 173) | ||||

| VEGF | VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | Regulator of angiogenesis | Endothelial cells | Endothelial cells, pericytes |

| Endothelial cell adhesion, motility, proliferation, survival (143, 177, 184, 187) | ||||

| Mural cell development during angiogenesis (62) | ||||

| Ang1 | Tie2 | Vessel stabilization, branching, and size (42, 48) | Pericytes | Endothelial cells |

| Ang2 | Endothelial sprouting, disassembly of endothelial-pericyte contacts (52) | |||

| Jagged1, DLL | Notch1 | Endothelial cell sprouting, angiogenesis | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Endothelial cells |

| Notch3 | Pericyte maturation (64, 68, 89, 97) | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Pericytes | |

| Wnt s’ | Fzd | β-Catenin-regulate angiogenesis, cell survival, and differentiation (127) | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Endothelial cells |

| ROR2 | Pericyte recruitment, polarity, and planar axis of endothelial cells and pericytes (40, 153, 182) | Endothelial cells, pericytes | Endothelial cells, pericytes | |

PDGF-β/PDGFRβ signaling

The PDGF signaling pathway is one of the primary mechanisms of endothelial-pericyte crosstalk in the microcirculation. During angiogenesis, the PDGF-β ligands interact with PDGFβ receptors on the surface of mural cells to activate a wide range of cellular responses, which include synthesis of angiogenic peptides, proliferation, and chemotaxis (74, 188). PDGF-β also prevents pericyte detachment and aberrant angiogenesis in response to high VEGF levels by suppressing downstream VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) signaling activity (54). This observation highlights the critical balance between VEGF and PDGF signaling in the vasculature, which regulates the timing for angiogenesis versus quiescence in response to hypoxia and injury.

In vivo studies using a PDGF Cre/lox system have revealed that constitutive activation of PDGFRβ by targeted insertion of an activating mutation in the pdgfrb murine locus promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation of mural cells (120). Recently, Cuervo et al. (35) reported success labeling NG2+, desmin+, PDGFRβ+ perivascular cells in the retina, and the brain using the PDGFRβ-P2A-CreERT2 mouse, further emphasizing the high level of PDGFRβ expression in pericytes. In general, murine models lacking PDGFβ or PDGF-β are embryonically lethal due to diffuse microvessels rupture secondary to reduced mural cell coverage (71, 156). For these reasons, PDGFRβ is considered one of the most useful markers for labeling pericytes in vivo and in vitro.

TGF-β signaling

TGF-β ligands are expressed by both mural and ECs and are critical modulators of EC function and pericyte differentiation (7, 58, 119, 121, 181). Changes in TGF-β can have profound consequences on angiogenesis. Studies have shown that increased TGF-β signaling results in greater vessel density and larger lumen diameter, whereas the opposite is seen with loss of TGF-β Signaling (204). One of the major diseases associated with TGF-β pathway mutations is hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), a disease characterized by pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, mural cell defects, and other systemic vascular abnormalities (108) (discussed later in this article).

The biological responses to TGF-β are regulated by two primary receptors: ALK1 and ALK5. Binding of TGF-β to ALK1 in ECs results in downstream phosphorylation (i.e., activation) and nuclear translocation of Smad1/5. By acting as a transcriptional factor complex together with Smad4 and other proteins, Smad1/5 activates genes associated with endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis. However, binding to ALK5 triggers opposite responses because this receptor triggers downstream phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the activation of a different gene cohort responsible for the induction of endothelial apoptosis and quiescence. Activation of TGF-β/ALK5 is responsible for mesenchymal cell differentiation into pericytes and VSMCs (6, 7, 74, 168). Depletion of TGF-β in a 10T1/2 (a mesenchymal cell line)-EC co-culture resulted in reduced differentiation of 10T1/2 into mural cells, as demonstrated by the lack of mural cell markers such as SMA and NG2 (29, 74, 121, 154). The critical role of TGF-β signaling in angiogenesis has been demonstrated through knockout mice experiments where mice deficient in TGF-β, ALK1, or ALK5 die in embryonic stages due to the inability to properly form functional microvessels that lack proper mural cell coverage (14, 42, 94). The angiogenic effects of TGF-β can also rely on crosstalk with other pathways. For example, TGF-β is known to increase GPR124 expression (G protein-coupled receptor 124). This Wnt-activated receptor is primarily responsible for establishing the cerebral circulation and the blood-brain barrier, a structure heavily dependent on appropriate pericyte coverage (5, 7, 36, 92).

VEGF signaling

The VEGF signaling pathway is considered a master regulator of angiogenesis through its effects on EC behavior during vessel morphogenesis. The VEGF signaling pathway’s importance is highlighted by studies demonstrating embryonic lethality in mice lacking VEGF pathway genes due to inappropriate vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis (130, 143, 144). The classic VEGF signaling paradigm is based on the VEGF-A ligand’s capacity to interact with endothelial VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2). VEGFR2 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that triggers a cascade of signaling pathways that influences multiple aspects of endothelial function such as adhesion, motility, proliferation, survival, and formation of endothelial-pericyte interactions. Given its profound effects on endothelial function, proper VEGF signaling output regulation is critical to prevent pathological angiogenesis, as seen in cancer and pulmonary hypertension (138, 171, 179, 182). For example, the expression of VEGFR1 can inhibit angiogenesis by competing with VEGFR2 for VEGF ligands. Various studies have shown that while knockout of VEGFR2 leads to disorganized vasculature, VEGFR1 knockout causes endothelial hyperproliferation leading to inappropriate vessel sprouting and branching morphogenesis (53). Besides VEGFR1, crosstalk with other signaling pathways regulates the VEGFR2 signaling output. For example, fibroblast growth factors (FGF) are instrumental in the activation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, stimulation of VEGFR2 expression, and ECs’ ability to respond to VEGF stimulation. ECs lacking FGF signaling are unresponsive to VEGF secondary to the downregulation of VEGFR2 expression resulting in loss of vascular integrity and reduced vascular morphogenesis (113).

Besides its effect on ECs, VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling can influence mural cell development and behavior during angiogenesis (59). Endothelial-derived VEGF is required to differentiate MSCs into mature mural cells, but in excess can disrupt pericyte recruitment and survival (105). Besides providing structural support, mural cells also release VEGF to support endothelial homeostasis and vessel function. Loss of mural cell-derived VEGF and VEGFR1 can have profound pathological consequences as demonstrated by the formation of dysfunctional vascular networks when healthy ECs are co-cultured with VEGF-deficient mural cells (37, 45). Inactivation of the VEGFR1 gene in mural cells using the Pdgfrb-CreERT2 murine model results in vascular hyperplasia and impaired angiogenesis. The ablation of pericytes using DTA system in Pdgfrb-CreERT2 mice promotes impaired endothelial sprouting in the postnatal retinal vasculature orchestrated by expression of VEGFR1-mediated VEGF signaling (43).

Angiopoietin/Tie2 signaling

Angiopoietin1-Tie2 is a signaling mechanism that orchestrates the complex communication of ECs and pericytes. The Tie2 receptor is mainly present on ECs, though evidence suggests their presence in mesenchymal cells and pericytes (23). Angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) is released by pericytes to facilitate vessel stabilization, branching, and size by binding Tie2 in the ECs (50). Cardiac-specific knockout of Ang1 leads to early vascular abnormalities that arise from flow-dependent defects and abnormal vascularization, which can be partially prevented by inhibition of angiopoietin 2 (Ang2) (46, 134). Ang2 is an antagonistic ligand that promotes endothelial sprouting while forcing disassembly of endothelial-pericyte contacts and the dissociation of pericytes from the vessel wall (40, 46). It has been demonstrated that the functional Tie2 receptor is also expressed at lower levels by both human and murine pericytes, and its silencing leads to aberrant endothelial sprouting and cell migration.

In contrast, the deletion of pericyte-expressed Tie2 in NG2-Cre mice transiently delays postnatal retinal angiogenesis and results in a pronounced pro-angiogenic effect (163). Also, inhibition of Ang2 increases the expression of cellular adhesion molecules, pericyte coverage, and reduced endothelial sprouting (46). In mouse models of diabetic retinopathy, pericyte loss temporally correlates with increased endothelial production of Ang2. Loss of pericytes results from apoptosis secondary to activation of a p53/integrin-dependent pathway and can be reversed by blocking integrin a3b1 (125). Recent transcriptome analysis in mice that Ang1 and Ang2 are targets for DKK2, a Wnt antagonist that promotes pericyte-EC interactions and angiogenesis through the Ang1/Tie2 pathway (194). The importance of Ang2 in cancer angiogenesis is further reflected in tumors rising in Ang2-deficient mice, where diameters of intratumoral microvessels were smaller, and pericyte coverage was significantly higher than in healthy vessels (115).

Notch signaling

Notch signaling has an established role in EC function and large vessel maturation. Mammals express four Notch receptors (Notch1–4), which interact with five membrane-bound ligands: Jagged1 (JAG-1), Jagged2 (JAG-2), and delta-like ligand (Dll) −1, −3, and −4. ECs express DLL-4, JAG-1, JAG-2, and Notch receptors 1 to 4, whereas pericytes and VSMCs express predominantly JAG-1 and Notch 1–3 (166). Notch signaling acts in several ways, most notably through the differentiation of ECs into tip and stalk cell phenotypes. Blockade of JAG- or DLL-mediated Notch Signaling promotes angiogenesis by suppressing VEGFR1 and promoting pericyte-EC interactions (85). The activation of Notch signaling promotes vascular basement membrane formation, a requirement for blood vessel maturation (199). Inhibition of Notch signaling or DLL-1 increases EC sprouting, while DLL-4 mediated activation of Notch1 leads to restricted tip cell phenotype and reduced angiogenesis (89). Activation of Notch receptors in the perivascular cells upregulates the expression of PDGFRβ, which promotes maturation of pericytes, as evidenced by increased expression of alpha-SMA (60, 93). Furthermore, recruitment and attachment of perivascular cells to the endothelial layer increases and helps support the formation of stable vessels (81, 162). In vivo, Notch knockout mice have early embryonic lethality due to widespread vascular abnormalities (192). Deletion of Notch1 and Notch3 in mice results in pericyte loss and vascular leakage, suggesting that Notch signaling is required for proper pericyte coverage and interaction with the endothelium (89, 199).

Wnt signaling

The Wnt signaling pathways have been known to affect angiogenesis, but their relevance to establishing endothelial-pericyte interactions has just begun to be elucidated. For the past 10 years, our lab has been interested in studying the role of Wnt pathways in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension, which is discussed later in this article (38, 128, 161, 196, 197).

One of the best-characterized pathways is Wnt/β-catenin pathway, whose primary effector molecule is β-catenin. Pathway activation leads to accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin resulting in the transcription of genes involved in cell survival and differentiation (122). Other alternative Wnt signaling mechanisms regulate angiogenesis and pericyte recruitment, such as the Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway that maintains the polarity and planar axis of ECs and pericytes. Wnt/PCP pathway is triggered by Wnt/Fzd interaction, but it acts in a b-catenin independent manner by activating the small GTPases Rac, Rho, and cdc42 (38, 148, 176). In addition to Wnts, other ligands such as BMP can activate both Wnt/β-catenin and Wnt/PCP pathway in pulmonary ECs (38, 126). We have shown that the interaction of endothelial-derived Wnt5a with Wnt/PCP receptors in lung pericytes is crucial in forming lung microvessels. Their deletion can result in vascular remodeling and elevated lung pressures in mice (197).

Role of Pericyte on Immune Surveillance and Inflammation

Pericytes possess the capacity to activate both the innate and adaptive immune systems by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and expression of specific pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (117, 151). Pericyte-dependent immune responses are activated when ECs activate PDGF signaling during vessel repair (116). Upon stimulation of the immune cascade, pericytes secrete IL-6, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-1, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and ICAM-1 in vivo (116, 132). Damaged pulmonary pericytes exposed to gram-negative bacteria lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were shown to increase secretion of ICAM-1, IL-6, CXCL1, and CCL2 in vivo. Specifically, studies show that pericytes increase expression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) when exposed to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pattern-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (116). It is speculated that the increase in TLR4 could play a role in early detection and propagating the innate immune system response during extreme episodes of systemic inflammation (i.e., sepsis).

Professional innate immune cells stimulate pericyte-dependent chemokines and cytokines secretion via TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ (104, 158). IL-17, when treated with TNF, was shown to recruit neutrophils to the site of injury. Concerning anti-inflammatory responses, pericytes treated with TGF-β experienced reduced MHC class II cell surface receptors and in IFN-γ supplemented by microarray analysis showing altered gene expression in pericytes (132). Pericytes possess the ability to express non-TLR PRRs such as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1 (NOD1), which helps activate antigen-presenting complexes containing foreign and self-antigens. This finding has led to the speculation that similar to adaptive immune cells, pericytes may have the ability to present antigens to CD4+ T-lymphocytes (67, 132).

Through their close interaction with ECs, pericytes play a pivotal role in the initial immune cell recruitment by responding to professional innate immune cells’ inflammatory cues. Pericytes are sensitive to IL-17 stimulation, which results in pericyte secretion of both CXCL8 and CXCL1 (116). Both of these pro-inflammatory factors, when bound to inflammatory cell receptors (i.e., CXCR 1, CXCr 2, etc.), promote the recruitment of neutrophils, natural killer cells, and macrophages (103, 137). Furthermore, pericytes themselves seem to behave as innate immune cells that detect alveolar damage, although this needs to be further validated (78).

Lung Diseases Associated with Pericyte Dysfunction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

PAH is a rare and life-threatening disease associated with abnormally high pulmonary pressures secondary to progressive loss and obstructive remodeling of small pulmonary arteries (138). PAH vascular lesions are characterized by the accumulation of excess VSMCs, fibroblasts, endothelial and inflammatory cells, and extracellular matrix (138, 164, 186). Regarding pericytes, it has been shown that lung pericyte behavior is also altered in PAH and could contribute to the small vessel loss and muscularization of the small pulmonary arteries (see Table 4 for a summary).

Table 4.

Summary of Lung Diseases Associated with Pericyte Dysfunction

| Disease | Pertinent abnormalities |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | Progressive loss and remodeling of small pulmonary arterioles Microangiopathy |

| Lung cancer | Irregular endothelial layer in vessels around tumor Inconsistent mural cell coverage |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Excessive secretion of extracellular matrix producing myofibroblast Progressive fibrosis of the parenchyma Loss of alveoli |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | Abnormal tangle of blood vessels Arteriovenous malformation in multiple organs |

| Asthma | Reversible airway obstruction and remodeling Chronic inflammation and airway smooth muscle hyperactivity Vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells proliferation |

| COPD | Dysfunctional pericyte behavior basement membrane thickening |

| COVID19 | Reduction in pericyte number near capillaries Vascular dysfunction Increased levels of prothrombotic and pro-inflammatory molecules |

| Sepsis | Systemic inflammation Microvascular dysfunction with altered blood flow Increased endothelial hyper-permeability |

In healthy lungs, pericytes are located in precapillary, capillary, and postcapillary beds with the most extensive coverage in microvessels’ postcapillary beds (4, 6, 41, 62, 153, 172). Morphologically, pericytes have a rounded cell body with a discoid nucleus that begins to flatten on postcapillary venules producing long branches that stem from the cell body and wrap around the ECs of the capillaries in a perpendicular manner (7, 172). Compared to healthy lungs, pericytes in PAH vascular lesions are dissociated from the ECs in the intimal layer and relocate the medial and adventitial layers. It has been shown that lack of appropriate pericyte coverage and endothelial dysfunction are common features of PAH vascular pathology, raising the possibility that failure of pericytes to associate with pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) in PAH contributes to small vessel loss by reducing structural stability and survival of newly formed microvessels (196). One of the reasons behind the inability of ECs and pericytes to establish communications is defective cell-cell crosstalk caused by inappropriate Wnt/PCP signaling. In pericytes, Wnt/PCP activation takes place when the Wnt5a ligand binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor ROR2 and Frizzled 7 (Fzd7) in the cell surface. This event results in ROR2 phosphorylation and downstream activation of Rho/Rac/cdc42 GTPases that carry out changes in pericyte motility and polarity (196). Most importantly, restoration of normal Fzd7 and cdc42 in PAH pericytes resulted in the recovery of their capacity to migrate and associate with vascular tubes as healthy donor lung pericytes (196).

Activation of Wnt/PCP occurs through the interaction of Wnt ligands with the Fzd surface receptors (202). While healthy PMVECs increase Wnt5a gene expression and protein production when co-cultured with healthy pericytes, PAH PMVECs fail to increase Wnt5a gene expression and protein production in response to pericytes. Moreover, it was also observed that Wnt5a expression and protein production are lower in PAH PMVECs in monoculture than healthy donor cells. To test whether endothelial-specific Wnt5a deletion could affect pericyte recruitment and vessel integrity in vivo, a tamoxifen-inducible endothelial-specific Wnt5a knockout (Wnt5 ECKO) mice was exposed to either normoxia, chronic hypoxia, or recovery conditions. While there were no differences between wild type and Wnt5a ECKO in normoxia and hypoxia, the Wnt5a ECKO in recovery demonstrated persistent pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, and vascular remodeling compared to WT. Confocal imaging of Wnt5a ECKO lung sections showed reduced pericyte coverage of microvessels accompanied by pericyte accumulation in the periphery of remodeled vessels. These studies demonstrated that Wnt5a production by PMVEC is required to ensure the appropriate recruitment of pericytes to pulmonary microvessels.

In PAH lungs, pericytes separated from the capillaries cluster within remodeled vessels and close to highly proliferative and apoptotic resistant pulmonary vSMCs. The phenotypic similarities between PAH PASMCs and pericytes are further evident when PAH pericytes are cultured in vitro. Similar to PAH PASMCs, PAH pericytes demonstrate significantly greater proliferation and survival rates that contrasts with their inability to properly migrate and associate with PMVECs during angiogenesis. When exposed to TGF-β1, pericytes purified from PAH lungs display a pro-proliferative and pro-migratory phenotype in culture(129). The hyperproliferation of PAH pericytes is linked to a metabolic switch to glycolysis (i.e., the Warburg effect) through the upregulation of PDK4. This enzyme suppresses the PDH complex and prevents pyruvate conversion to acetyl-CoA. PDK isoforms are also upregulated in PAH PASMCs and drive hyperproliferation by suppressing apoptosis and activation of multiple trophic pathways. Given the similarities between PAH pericytes and PASMCs, pericytes may be part of a continuum that results in muscularization and remodeling of precapillary arterioles in PAH.

While the origin of the PASMCs responsible for the muscularization of PAH lesions is incompletely understood, recent studies have shown that resident lung progenitor cells can act as a source of SMCs in injury. In two landmark studies, it was shown that progenitor cells in proximal vessels differentiate into SMCs in response to chronic hypoxia and relocate to non-muscularized microvessels (145, 146). Once relocated, these SMC-like cells accumulate in the medial layer and contribute to PA hypertrophy, a known hallmark of hypoxia-induced PH. Regarding pericytes, Ricard and colleagues’ research provides data supporting the possibility of pericytes in PAH undergoing a transdifferentiation stage in which pericytes can further differentiate into VSMCs. Using NG2DsRedBAC mice that were treated in hypoxic conditions, they discovered an increase in alpha-SMA presenting pericytes after 14 days of oxygen deprivation. These experiments further support the claim that pulmonary pericytes are involved in vascular remodeling by serving as a source for SMCs (129).

Our group also found similar increases in alpha SMA expression levels in the Wnt5a conditional knockout mice compared to the wild-type mice when examining immunofluorescence of lung cross-sections (197). Using a lineage tracing approach, we recently showed that hypoxia-exposed NG2-tdT mice demonstrated a 3-fold increase in tdT+ cells within the SMC-rich medial layer. Using a combination of RNA-seq and bioinformatics, we have shown that the genetic profiles of PAH PASMCs and pericytes are similar compared to their healthy counterparts, supporting the existence of a similar genetic landscape responsible for the phenotypic similarities between these cell types in PAH. Moreover, this strategy has also allowed us to begin identifying the genetic differences responsible for the PAH pericyte behavior both in PAH and in the murine model of hypoxia-induced PH. Through a combination of in vitro and in vivo studies, SDF1 was shown to be a key player in driving NG2+ mural cells to participate in vascular remodeling and triggering pathological PAH pericyte activity. Our lab has demonstrated that CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 presents mice from developing hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (195). This finding is in line with recent observations that have shown the therapeutic potential of targeting SDF1 in reducing PA muscularization in rat models of PAH (23).

Lung cancer

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths for both men and women worldwide (150). About 80% to 85% of lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) (149), demonstrating a high index of invasiveness, tissue destruction, and metastasis in 55% of patients upon presentation (26). Current management for NSCLC includes surgery (except in patients with metastasis), chemotherapy, and radiation alone or combined (198). Despite aggressive treatment, the prognosis of the patient’s NSCLC remains low, with an estimated 5-year survival of 24% (173). As with other malignancies, lung cancers require a constant supply of blood, gases, and other nutrients to support growth, invasiveness, and metastasis (17). In contrast to the vasculature of healthy tissues, tumor-associated blood vessels are more massive, leakier, and exhibit a tortuous appearance throughout their length (16, 69). Histological analysis of tumor vessels reveals an irregular endothelial layer surrounded by a dense layer of extracellular matrix and inconsistent coverage of mural cells (102).

Cancer cells produce various pro-angiogenic chemokines such as VEGF, PDGF, and EGF, which help recruit ECs and pericytes away from neighboring healthy vessels (25). By hijacking the healthy circulation, tumor cells take advantage of available nutrients and oxygen at healthy tissues (57). Over the past 10 years, anti-angiogenic chemotherapies have shown efficacy in reducing tumor burden and slowing the progression of NSCLC. Still, these therapies’ long-term success is limited by the development of drug resistance and toxicity (27). Given the importance of pericytes to vascular maturation and stability, several studies have been carried out to clarify the contribution of pericytes to tumor angiogenesis in NSCLC.

Tumor progression is dependent upon new vessel formation. Pericytes have been shown to express angiogenic genes such as FGF, IGF-I, MMP-2, PDGF, TGF-β3, and VEGF, which are also present on ECs (10). Also, pericytes expressed matrix metalloproteinases that assist in the breakdown of basement membrane components, facilitating the migration of pericytes and ECs into the neovessels. Pericytes contribute to angiogenesis by forming segments of the vascular lumen called tubes. This tube formation by pericytes is promoted by growth factors found in malignant tumor cells. Despite the previous belief of endothelial-only tube formation, a study has shown that a subpopulation of these microvessels lacks ECs. It was also demonstrated that many pericytes invade tumors and form vessels in the absence of ECs (9). Although pericytes have shown the ability to form angiogenic tubes, the participation of ECs and their interaction with pericytes is essential for angiogenesis. By identifying and targeting the angiogenic growth factors that either activate or inhibit these pericytes, treatments against malignant angiogenesis in NSCLC can be made (27).

As previously discussed, the VEGF signaling pathway is a significant driver of angiogenesis in systemic and pulmonary circulations (135). Bevacizumab (BV) is a VEGF pathway inhibitor that has been shown to reduce NSCLC tumor growth by 77% (27). However, it has been shown that 20% to 30% of patients with NSCLC develop resistance to BV, as evidenced by tumor regrowth and neovascularization (182). NSCLC blood vessels that acquired BV resistance were characterized by greater pericyte coverage and less tortuous, normalized revascularization (27). It is speculated that resistance to BV is triggered by tumor hypoxia and the production of non-VEGF pro-angiogenic factors. Production of FGF ligands has been described in BV-resistant NSCLC and is associated with increasing the blood vessels’ maturity, thus providing support for neovascularization.

Interestingly, FGF has been shown to induce the migration of pericytes in NSCLC tumors (27). The resistance that NSCLC tumors develop against anti-angiogenic agents presents a challenge for new therapies against this malignant disease. Therefore, other pathways, such as the PDGF signaling pathway, have been studied to determine if their inhibition can solve this tumor resistance complication.

PDGF signaling pathway is involved in pericyte recruitment in NSCLC. It has been shown that upon treatment with anti-VEGF, the PDGF receptors in tumor cells increase and correlate with increased resistance to therapy (44). However, if the PDGF pathway is blocked, tumor vessels are destabilized by reducing pericyte-endothelial contacts (13). A study demonstrated that treatment with imatinib, a drug that blocks PDGF and VEGF tyrosine kinase receptor activity, could significantly reduce vascular density in NSCLC tumor growths (177). While these studies suggest that targeting PDGF and VEGF could be useful therapeutically, it is worth pointing out that a significant side effect of these therapies is damage to normal vessels, predisposing patients to edema and vascular hemorrhage (44). Thus, further research is needed to find safer and more suitable anti-vascular therapies against NSCLC.

The ability to target pericytes, in addition to EC, would possibly increase the effectiveness of anti-angiogenic therapies in cancer. For example, targeting pericytes leads to pericyte detachment from the tumor vasculature, therefore, damaging the tumor’s blood supplies. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor Gleevec or SU6668 inhibits pericyte PDGF signaling, can block tumor angiogenesis more efficiently when used in synergy with VEGF inhibitors (13).

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive interstitial lung disease with a median patient survival of 3 to 5 years following diagnosis (48). Histologically, IPF can be characterized by the appearance of ECM-producing myofibroblasts that drive progressive fibrosis of the parenchyma and loss of alveoli (112). Myofibroblasts and pericytes are both derived from MSCs and display some overlap in structure and function. Multiple studies have observed that lung pericytes derived from IPF patients proliferate and differentiate into myofibroblasts in vitro, undergoing a transition state known as the pericyte-myofibroblast transition (PMT) (77, 96, 136, 184). Following PMT, pericyte-derived myofibroblasts promote pathogenic remodeling of the lung environment by contracting the parenchyma, releasing ECM, and synthesizing pro-fibrotic mediators (77, 136). PMT also compromises endothelial stability as activated pericytes detach from endothelial walls and move into the interstitial space, leaving vessels vulnerable to leakage and apoptosis (142).

Cytokines like TGF-β are strongly linked to pericyte response to injury and to PMT. Multiple studies have shown TGF-β stimulates the development of pro-fibrotic pericyte phenotypes by increasing expression of Collagen I, alphasmooth muscle actin, CTGF, and fibronectin (77, 79, 193). Recent studies have elucidated specific pathways that may play a significant role in TGF-β-induced PMT. For example, although TGF-β appears sufficient to induce PMT and migration in vivo, pericytes fail to mount a migratory response to TGF-β in vitro (189). Leaf et al. (96) propose that the pro-fibrotic effects of TGF-β on pericytes are carried out by the cytoplasmic proteins MyD88 and IRAK4, associated with inflammatory and fibrotic responses to tissue injury. Sava et al. (136) propose a model through which TGF-β induces a pathway that promotes PMT and matrix invasion through a mechanosensitive process. There is a minor population of FoxD1 progenitor-derived/Coll-GFP+ pericytes in normal lungs that are involved in matrix remodeling and can express collagen-I(a)1 (77). This subtype may respond to TGF-β directly by producing collagen and fibronectin-rich ECM that creates an environment that induces other pericytes to undergo PMT (136). This process occurs through an MKL-1/MTRFA mechanotransduction pathway and results in a remodeled extracellular matrix that contributes to the fibrotic symptoms characteristic of IPF (136). Besides TGF-β, Notch1 and PDGF also mediate pericyte activation in IPF. Recently Wang et al. (184) found that elevated expression of Notch1 and downstream Notch1 effectors PDGFRβ and ROCK1 in lung tissues from IPF patients and murine models of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Significantly, inhibition of Notch1 in mice inhibited PMT and reduce lung fibrosis, offering another potential therapeutic approach to IPF. Unlike TGF-β, and Notch, PDGF-β has a strong pro-migratory effect on pericytes (189), suggesting it may play a role in forcing pericytes away from vessels to undergo PMT at sites of fibrosis.

The studies above lay some of the groundwork to elucidate the mechanisms underlying PMT. However, further research may help understand these pathways and discover new ways involved in pericyte activation. Further research on PMT inhibitors may also prove valuable, primarily as such inhibitors can provide new therapeutic approaches that can prolong the median survival time and improve the quality of life of IPF patients.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

HTT, also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal dominant vascular disorder that affects 1 in 5000 individuals worldwide. HHT is characterized by an abnormal tangle of blood vessels connecting arteries and veins without a capillary bed, forming a sizeable arteriovenous malformation in multiple organs (124, 191). Another common clinical feature is red spots in the nasal septum, oral mucosa, and gastrointestinal mucosa known as a Telangiestica (108). Although the classical elements of HHT are similar across all the genotypes, specific vascular malformations are associated with each disease’s subtype. The two most common forms of HHT arise from mutations in Endoglin (ENG, Type 1 HHT) gene or the ACVRL1 gene encoding activin receptor-like kinase (ALK1, Type 2 HHT) (82, 107). Interestingly, these genes code for receptors involved in BMP and TGF-β signaling. The mutations are associated with severe disruption of endothelial-pericyte communications that result in dilated and fragile vessels prone to rupture hemorrhage.

Previous research has suggested that increased angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of HHT and this may contribute to the appearance of systemic and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (51, 165). Given that TGFβ/BMP signaling is vital for vascular morphogenesis and angiogenesis, mutations that result in defective signaling affect vessel stability due to lack of pericyte recruitment and maturation. Current emerging treatment for HHT is proposed to increase the number of pericytes associated with the endothelium (80). Thalidomide has been shown to increase the number of pericytes surrounding vessels and improves their attachment to the endothelium, thereby stabilizing the vessel and prevent bleeding from AVMs (97). BMP signaling is also required by vSMCs for maturation and differentiation. Although the link between BMP signaling, pericytes, and HHT remains undefined, it is essential to point out that some HHT individuals carrying ALK1 mutations can develop PAH (56).

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic lung disease physiologically defined as reversible airway obstruction (55). Pathologically, asthmatic airways feature chronic inflammation with airway smooth muscle hyperreactivity, which facilitates airway remodeling (11). Both smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy characterize airway remodeling in asthma. In addition to airway changes, mice exposed to respiratory ovalbumin demonstrate vascular smooth muscle and EC proliferation (133). An alternative asthma model, the house dust mite model, revealed the presence of pericytes in the subepithelial airway wall, suggesting that pericytes may play a role in the airway wall’s altered cellular composition in mouse models of asthma (83). Another group who first studied this model demonstrated similarly increased cellularity in the vasculature (114). This work indicates that pericytes may be involved in cell recruitment, accumulation, and differentiation, contributing to lung tissue damage associated with asthma.

Signaling pathways relevant to pericyte function have demonstrated relevance in the pathogenesis of asthma. It is known that pericytes can produce VEGF to support endothelial homeostasis and vessel stability. The IL-13 mouse model of asthma has elevated VEGF production levels, causing increases in angiogenesis and vascular leaking (98). Also, VEGF levels in biologic fluids increase proportionally with the severity of asthma (76). These studies indicate that VEGF signaling and pericytes in asthma’s pathogenesis may be an avenue for further investigation. Another signaling pathway of interest is the PDGF-β/PDGFR-B. PDGFRβ plays a vital role in pericyte proliferation and migration and many other homeostatic functions (7). In OVA-sensitized mice, overexpression of PDGF-β leads to airway SMC proliferation and increased airway hyperresponsiveness (72, 86). While pericytes were not directly studies by these groups, the known chemotaxis of pericytes in response to PDGF could imply a pericyte contribution to the increase in muscularization of these smooth muscle bundles. Additional future studies on the relationship between pericytes and asthma should look closely into PMT mechanisms, though direct contributions to the disease pathology require further investigation.

COPD

While research regarding the relationship between pulmonary pericytes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an active investigation area, some studies suggest a role for pericytes either by implications of signaling pathways known to be associated with dysfunctional pericyte behavior or pathologic behavior of other cell types known to depend on pericytes for maintenance of homeostasis. In response to exercise training, COPD patients display blunted improvements in exercise capacity and muscle angiogenesis when compared to controls. An observed loss of pericyte-EC interactions in COPD patients undergoing exercise therapy causes compensatory basement membrane thickening and dysfunctional pericyte coverage. The loss of pericyte-endothelial contacts negatively correlates with the plasmatic level of F2-IsoP, a marker of oxidative stress (21). CD146, a cell surface marker found on most pericytes and ECs, is a part of the endothelial junction and facilitates cell-cell interactions (91). CD146 expression is decreased in the lung tissue of smokers with COPD and experimental rat models exposed to second-hand smoke. In contrast, soluble CD146 (sCD146) was increased in the plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (91). Loss of CD146 function resulted in damaged pulmonary endothelial integrity (increased vascular permeability, inflammatory cell migration), and emphysema (91). Furthermore, increased CD146 expression in alveolar macrophages is elevated in COPD patients and may contribute to excessive inflammation during COPD exacerbations (190). While most of the literature has focused on investigating CD146 expression in ECs and the endothelium of COPD patients, pericytes’ role in contributing to CD146 presentation should also be considered. In mice, CD146 in brain pericytes and ECs is essential in forming a mature and stable blood-brain barrier (29). The expression of CD146 in lung pericyte and ECs and their role in angiogenesis and vascular maintenance is an area in which further studies are required.

Ang2 is a growth factor functioning as part of the AngTie signaling pathway, a pathway important in regulating angiogenesis and vessel maturation. Ang2 binds to the Tie2 receptor and functions as an agonist, facilitating the loosening of pericyte-EC interactions, leading to vessel destabilization (3). Ang2 is shown to be increased in the serum of COPD patients during exacerbations (31). It is hypothesized that increased Ang2 expression results in the vascular permeability and remodeling in chronic bronchitis patients. Furthermore, there is a strong positive association between Ang2 and VEGF, suggesting a possible interaction wherein high concentrations of Ang2 and VEGF promote angiogenesis (15). There is an increased VEGF expression in patients with a chronic bronchitis pathology, most prominently in bronchiolar and vSMCs and epithelium (99). VEGF’s increase correlates with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (90). VEGF may increase bronchial vascularity and vascular permeability and result in edema and airway remodeling in chronic bronchitis patients (84). However, there is a decrease in VEGF expression observed in patients with emphysema that might induce alveolar cell apoptosis, causing the microvessel loss (87). Abnormal pericyte function may be responsible for alterations in VEGF expression levels and result in the microvascular changes associated with COPD but this needs to be further explored.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response predominantly caused by microbial infections and represents the most frequent causes of mortality in ICU patients (159). Microvascular dysfunction such as altered blood flow decreased capillary density, and increased endothelial hyper-permeability is associated with the development of sepsis-related multiorgan failure due to pericyte loss, both evident in experimental and human sepsis (199, 203). Pericytes seem to serve a critical role in immune cell ingression into the injured vascular space and promote vascular stability. Lack of pericytes encapsulating vessels has shown to result in hyperimmune infiltration, suggesting that pericytes play a fundamental role in regulating immune cell permeability (12). Furthermore, in vitro microfluidics experiments have shown that human lung pericytes also regulate vasoconstriction and vasculogenesis via paracrine signaling following an injury to the lung (5, 6).

The mechanisms by which pericytes influence vascular integrity and blood pressure homeostasis during systemic inflammatory processes are incompletely understood. Upon interactions with bacterial gram-negative LPS, pericytes secrete chemokines and cytokines by activating TLR4. TLR4 activates the intracellular signaling pathway that stimulates the activation of the innate immune system. Following stimulation, increased expression of both vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM1) and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) result in increased adhesion of leukocytes to the pericyte layer (95). Loss of lung pericytes is a feature of vascular dysfunction in the mouse model of cecal puncture-induced lung injury. Pericyte loss appears to be associated with an increase in Fli-1, a transcription factor associated with malignancy and hematological disorders (100). Inhibition of Fli-1 through Cre/Lox recombinase technology resulted in higher levels of NG2 expression, greater pericyte cell population density, reduced vascular leak, and overall improved survival of septic mice. Elevation of Ang2 production is associated with pericyte loss in the LPS-induced sepsis murine model, resulting in increased vascular permeability and left ventricular dysfunction (203).

In contrast, downregulated Tie2 and HIF-2a/Notch3 expression resulted in a dramatic reduction of pericyte/EC coverage in mice’s lungs (199). Inhibition of metalloproteinases and independent functions of metalloproteinases in sepsis, such as VEGF signaling and MVEC leukocyte interactions, initiates the activation of TIMPs (174). In sepsis-associated multiple organ dysfunction (MOD), tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 3 (TIMP3) are partially expressed by lung pericytes, which aid in the development of microvascular ECs by suppressing metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif 1 (ADAMTS-1), thus promoting vascular stability (106). Therefore, future studies should focus on possible therapeutic interventions to restore pericyte-EC connections and accelerate the clearance of inflammation and endothelial barrier stability.

COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread rapidly across the globe with over 65 million confirmed cases and more than 1.5 million deaths (as of 12/04). As the disease progresses, some infected patients develop severe pneumonia in which the alveoli swell and fill with fluid, which may prove fatal (167, 169). Histologically, analysis of postmortem biopsies from COVID-19 patients has revealed a dramatic reduction in the number of pericytes around the alveolar capillaries of COVID-19 patients compared to biopsies from healthy controls (24). This finding has led to speculation concerning the role of pericytes in developing the vasculopathy and coagulopathy associated with COVID-19 (1).

There is evidence of SARS-CoV-2 gaining entry to human respiratory cells by attaching to a receptor named angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 (ACE2) (101). Efforts to elucidate the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection mainly center around epithelia, given that ACE2 mRNA is abundantly present in human lung epithelia (65). However, multiple studies using bulk, single-cell, and nuclear RNA sequencing have shown that pericytes in the brain and heart demonstrate higher ACE mRNA expression compared to other vascular cells (28, 175). Using these genetic databases, He and colleagues have recently proposed a “COVID-19-pericyte hypothesis,” which posits that vascular injury associated with COVID-19 is dependent on direct viral infection of pericytes through fenestrations and irregular cell-cell junctions in the endothelial layer (70). In this model, infected pericytes become activated and contribute to vascular dysfunction by producing pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic factors that promote platelet aggregation, fibrin deposition, and thrombosis. It is important to point out that this model appears to be most relevant to heart and brain vasculatures since the analysis of murine lung scRNA-Seq data only demonstrated ACE2 expression in alveolar type 2, not in pericytes or ECs. Also, there were no in vitro studies showing the capacity of SARS-CoV-2 to infect pericytes in vitro, leaving many open questions that must be addressed before this hypothesis can be used as part of plans to develop new COVID-19 therapeutics.

| Research gaps and deficiencies | Improvement |

|---|---|

|

| |

| • Poorly understood precise properties and developmental sources of pericytes • Heterogeneous and a tissue- and context-dependent manner of the origin of pericytes • A tissue- and context-dependent manner for different morphology and expression markers • Confusion and controversial identity when compared with other mural cells, such as smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, due to unavailable single cell marker • The function, characterization, and identification of subtypes of pericytes • Pathological or protective role of pericytes in different disease settings • Maintain a physiological pericyte culture without any lineage change in vitro |

• Single-cell RNAseq to identify unique pericyte markers in human vs. other species, such as rodents • Identify pericyte specific markers in different tissues • Creation of pericyte specific Cre-ER transgenic animal model |

Conclusions

Beyond their role as mural cells, pericytes carry a wide range of essential functions critical for the maintenance and regeneration of blood vessels. We are only beginning to understand how pericytes participate in the pathogenesis of lung diseases. Still, there is enough information to support their contribution to fundamental pathological events such as fibrosis and vascular remodeling. There is much to learn concerning the potential for pericytes to differentiate into other cell types but is tempting to speculate whether pericytes could serve as the basis for regenerative pulmonary medicine strategies. It is also essential to recognize that it is impossible to understand pericyte biology without considering the crosstalk that exists with ECs during quiescence and angiogenesis. Future research needs to be carried out to elucidate how the different signaling mechanisms involved in endothelial-pericyte crosstalk are integrated into either physiologic or pathological responses in the setting of lung injury and repair. Given the unmet need for novel therapeutics for the lung diseases discussed in this article, expanding our understanding of lung pericyte biology can open exciting opportunities to revolutionize clinical medicine and our understanding of lung biology.

Didactic Synopsis.

Major Teaching Points

Pericytes can be identified by their location within the basement membrane of capillaries, long cellular processes enveloping the vessel circumference, and physical contact with the endothelial cell membrane through adhesion plaques and gap junctions.

Multiple cellular markers have been used to identify pericytes but no single marker can differentiate pericytes from other mural cells.

Under certain conditions, pericytes can act as progenitor cells and differentiate into other cell types (e.g., adipocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells).

The establishment of endothelial-pericyte contacts during late angiogenesis is essential to ensure vessel viability and functionality and requires coordinated production of cytokines and chemokines by endothelial cells and pericytes.

Loss of pericyte coverage, inappropriate production of cytokines, extracellular matrix components, and differentiation into pro-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic cells are commonly found in multiple lung diseases.

Acknowledgements