Abstract

Transcriptional enhanced associate domain (TEAD) binding to co-activator yes-associated protein (YAP1) leads to a transcription factor of the Hippo pathway. TEADs are regulated by S-palmitoylation of a conserved cysteine located in a deep well-defined hydrophobic pocket outside the TEAD·YAP1 interaction interface. Previously, we reported the discovery of a small molecule based on the structure of flufenamic acid that binds to the palmitate pocket, forms a covalent bond with the conserved cysteine, and inhibits TEAD4 binding to YAP1. Here, we screen a fragment library of chloroacetamide electrophiles to identify new scaffolds that bind to the palmitate pocket of TEADs and disrupt their interaction with YAP1. Time- and concentration-dependent studies with wild-type and mutant TEAD1–4 provided insight into their reaction rates and binding constants and established the compounds as covalent inhibitors of TEAD binding to YAP1. Binding pose hypotheses were generated by covalent docking revealing that the fragments and compounds engage lower, middle, and upper sub-sites of the palmitate pocket. Our fragments and compounds provide new scaffolds and starting points for the design of derivatives with improved inhibition potency of TEAD palmitoylation and binding to YAP1.

Screening of reactive chloroacetamide fragments yields covalent allosteric inhibitors of TEAD binding to YAP1. Follow-up time- and concentration-dependent characterization of novel inhibitor scaffolds is reported.

Introduction

Transcriptional enhanced associate domains (TEADs) engage transcriptional co-activators yes-associated protein (YAP1) or its paralog transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) through a high affinity protein–protein interaction.1 YAP1 and TAZ possess a transactivation domain required for recruiting Mediator to initiate transcriptional activity, while TEAD1–4 possess the DNA-binding domain.2 Together, the TEAD·YAP/TAZ complex controls expression of Hippo signaling pathway such as CTGF and Cyr61.3 The Hippo tumor suppressor pathway controls organ growth, stem cell differentiation, tissue and immune homeostasis. In normal tissue, Hippo kinases phosphorylate YAP and TAZ sequestering them into the cytoplasm through protein–protein interaction with 14-3-3 proteins or degradation in the proteasome.4 When Hippo pathway signaling is deactivated, unphosphorylated YAP and TAZ enter the nucleus where they bind to TEAD transcription factors to initiate transcription of genes such as CTGF and Cyr61.3 More recent studies have shown MYC, WNT5A/B, EGFR, and PD-L1 among others are also TEAD target genes.5

In addition to a DNA-binding domain, all four TEADs (TEAD1–4) possess an additional domain that engages YAP1 and TAZ through a protein–protein interface that is larger than 1000 Å2.6 The domain of YAP1 that binds to TEAD consists of an α-helix and an Ω-loop.6 Most of the affinity is concentrated at the Ω-loop binding site,7 but it is believed that the α-helix enhances the binding affinity through cooperative effects. The TEAD surface at the TEAD·YAP/TAZ interface is devoid of a well-defined binding pocket, making it highly challenging to develop small-molecule orthosteric inhibitors of the protein–protein interaction.6 Crystal structures of TEADs have revealed the presence of a palmitate binding pocket that is located deep within the TEAD structure outside the TEAD·YAP interface.8 Palmitoylation regulates TEAD stability and half-life without affecting its localization or binding to YAP1.9

The palmitate pocket is large and well-defined and can easily accommodate a small molecule. We demonstrated this recently with the development of a small molecule, TED-347, which formed a covalent bond with the conserved cysteine of the pocket.1a The compound occupied the palmitate pocket and inhibited YAP1 binding to TEAD4 as established by a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay and biolayer interferometry (BLI). The compound was shown to inhibit TEAD transcriptional activity in mammalian cells. We also recently reported the design of small molecules with a cyanamide reactive group based on the TED-347 scaffold.10 The resulting compound, TED-642, reacts with a substantially improved reaction rate that corresponds to a reaction half-life in the minutes compared to hours for TED-347. Since then, numerous small molecules have been reported to bind to the palmitate pocket in a covalent11 and non-covalent mechanism.12 All these efforts have focused on the identification of small molecules that compete with palmitate. Here, we screen a library of chloroacetamide fragments and small-molecule electrophiles to identify covalent inhibitors of both TEAD palmitoylation and TEAD binding to YAP1. Among the small molecules that inhibited the protein–protein interaction, mass spectrometry analysis with wild-type and mutant protein showed that the compounds bind to the palmitate pocket and form a covalent bond with the conserved cysteine. Follow-up concentration- and time-dependent studies confirmed that the compounds are covalent inhibitors and provided insight into their reaction rates and binding constants. We explored these fragments and compounds against the three other TEADs to get insight into compound specificity. These compounds provide starting points for the development of small-molecule inhibitors of TEAD palmitoylation and binding to YAP1.

Results and discussion

Covalent fragment screening

The three-dimensional structure of TEAD in complex with YAP1 reveals a challenging protein–protein interface for small-molecule inhibition (Fig. 1A). However, we previously established that the palmitate binding pocket of TEADs is highly accessible and covalent bond formation at the conserved cysteine within the pocket can lead to inhibition of the TEAD·YAP1 protein–protein interaction (Fig. 1B). Here, to identify small molecules that bind to this pocket and inhibit TEAD binding to YAP1, an in-house library of 658 chloroacetamide electrophiles was screened for inhibition of TEAD4 binding to YAP1. The workflow that was used to identify hits and follow-up studies is shown in Fig. 1C. TEAD4 was incubated with fragments and compounds at 50 μM for 24 h at 4 °C prior to the addition of fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide and measurement of fluorescence polarization (Fig. S1†). Thirty-nine hits with inhibition greater than 40% were selected for follow-up studies. Hits were first tested in a concentration-dependent manner using our FP assay with wild-type TEAD4, TEAD4C367S mutant and an unrelated protein–protein interaction of the urokinase receptor uPAR and an α-helical peptide AE-147 (ref. 13) (Tables 1–4 and Fig. 1–3). Compounds that selectively inhibited TEAD4 and not TEAD4C367S mutant or uPAR were tested by whole-protein mass spectrometry to confirm covalent bond formation to TEAD4. A representative set of two compounds per class were tested in a time- and concentration-dependent manner for inhibition and covalent bond formation, as well as inhibition of TEAD1–3 binding to YAP1. Compounds were selected based on their inhibition profile, ability to form an adduct specifically at the conserved cysteine and chemical structure. Initially, we focused on compounds with the highest extent of inhibition based on IC50 values from FP data, then selected candidates that formed the strongest bond with the cysteine based on adduct formation using data from the intact protein mass spectrometry. Finally, we visually inspected the chemical structures and picked compounds with different substituents to maximize diversity in the final set of compounds.

Fig. 1. (A) Stereoview of TEAD4 binding to YAP1 (PDB: 5OAQ1b). TEAD4 is shown in transparent Connolly surface representation. YAP1 is depicted in pink ribbon representation. The Ω-loop and α-helix regions of YAP1 are highlighted with dashed ovals. Black arrows point to fatty acid myristate shown in yellow capped-sticks representation. The fatty acid is bound in the palmitate pocket of TEAD4. (B) The structure of TEAD2 in a covalent complex with TED-347 (PDB: 6E5G13) was superimposed onto the structure of the TEAD4-myristate complex (PDB: 5OAQ1b). The Connolly surface shown is that of TEAD4. Myristate (carbon and oxygen in yellow and red, respectively) and TED-347 (carbon, nitrogen, and fluorine in purple, blue, and cyan, respectively) are shown in capped-sticks representation. Sub-sites within the palmitate-binding pocket are highlighted with dashed boxes. (C) The overall workflow followed in this work to identify covalent TEAD inhibitors.

Dihydropyrazole hit compounds.

| Compound |

|

TEAD4 MS adduct at 24 h 4 °C (%) | TEAD4 FP IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | TEAD4C367S IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | uPAR·AE-147 IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | LipE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | ||||||

| 1 (HPV-027) |

|

|

45, 9a | 4.7 ± 0.3; maxb 46% | NIc | NI | 2.8d |

| 2 (RHA-059) |

|

|

85, 15 | 2.2 ± 0.8; max 40% | NI | NI | 2.7 |

| 3 (RHA-083) |

|

|

64, 18 | 6.0 ± 1.2; max 62% | NI | NI | 2.1 |

| 4 (RHA-076) |

|

|

38, 21 | 5.9 ± 2.4; max 52% | NI | NI | 2.0 |

| 5 (RHA-049) |

|

|

27 | 1.5 ± 0.4; max 41% | NI | NI | 1.5 |

| 6 (RHA-079) |

|

|

27 | 3.8 ± 1.1; max 41% | NI | NI | 2.0 |

| 7 (RHA-362) |

|

|

42 | 1.1 ± 0.3; max 39% | NI | NI | 3.1 |

| 8 (RHA-363) |

|

|

78, 15 | 3.3 ± 1.0; max 48% | NI | NI | 2.6 |

| 9 (RHA-002) |

|

|

38, 30 | 5.8 ± 3.9; max 45% | NI | NI | 2.6 |

| 10 (RHA-056) |

|

32, 10 | 7.8 ± 6.4; max 67% | NI | NI | 1.6 | |

Second protein–compound adduct.

Maximum inhibition.

NI, no inhibition.

LipE = pIC50 − clog P.

Time-dependent whole-protein mass spectrometry at 4 °C.

| Compound | k inact/KI (M−1 s−1) | K I (μM) | t ∞ (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (RHA-059) | 13.5 ± 0.9 | NDa | ND |

| 8 (RHA-363) | 8.3 ± 4.9 | 37.7 ± 19.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| 13 (RHA-302) | 5.1 ± 2.1 | 17.3 ± 6.6 | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| 21 (MAT-241) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 45.8 ± 12.0 | 3.3 ± 0.5 |

| 23 (TED-564) | 2.4 ± 0.0 | ND | ND |

| 26 (TED-567) | 28.1 ± 13.3 | 94.0 ± 38.5 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 36 (RHA-337) | 0.3 ± 0.0 | ND | ND |

| 37 (RHA-349) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

ND, not determined; rate constant versus compound concentration plot did not plateau. Linear function was fit to determine kinact/KI.

Peptide-like hit compounds.

| Compound |

|

TEAD4 MS adduct at 24 h 4 °C (%) | TEAD4 FP IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | TEAD4C367S IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | uPAR·AE-147 IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | LipE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | ||||||

| 11 (MAT-218) |

|

|

|

15 | 4.0 ± 0.2, maxb 40% | NIc | NI | 0.3d |

| 12 (RHA-010) |

|

|

|

51, 12,a 15 | 1.1 ± 0.3, max 39% | NI | NI | 1.0 |

| 13 (RHA-302) |

|

|

|

55, 18, 17 | 1.4 ± 0.3, max 31% | NI | NI | 0.7 |

| 14 (RHA-253) |

|

|

|

31 | 7.4 ± 3.7, max 49% | NI | NI | 0.0 |

| 15 (RHA-254) |

|

|

|

25 | 4.4 ± 1.1, max 36% | NI | NI | −0.3 |

| 16 (RHA-250) |

|

|

|

37 | 5.5 ± 1.3, max 45% | NI | NI | 0.2 |

| 17 (RHA-132) |

|

|

|

12, 20, 30 | 13.0 ± 2.3, max 67% | NI | NI | 0.6 |

| 18 (RHA-013) |

|

|

|

ND | 20.7 ± 1.5, max 100% | 27.9 ± 1.3 | NI | 1.6 |

| 19 (RHA-252) |

|

|

|

32 | 4.8 ± 1.9, max 41% | NI | NI | 0.5 |

| 20 (RHA-263) |

|

|

|

47 | 10.5 ± 2.7, max 42% | NI | NI | 0.7 |

| 21 (MAT-241) |

|

46, 11, 20 | 4.2 ± 1.4, max 37% | NI | NI | 2.3 | ||

Additional protein–compound adduct detected in the mass spectrum.

Maximum inhibition.

NI, no inhibition.

LipE = pIC50 − clog P.

Piperazine, piperidine, and imidazolidine hit compounds.

| Compound |

|

TEAD4 MS adduct at 24 h 4 °C (%) | TEAD4 FP IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | TEAD4C367S IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | uPAR·AE-147 IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | LipE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | R1 | ||||||

| 22 (TED-561) | N |

|

73 | 4.9 ± 0.7, maxb 49% | NIc | NI | 3.3d |

| 23 (TED-564) | N |

|

100 | 11.1 ± 1.5, max 44% | NI | NI | 2.8 |

| 24 (TED-581) | N |

|

38 | 22.8 ± 4.7, max 48% | NI | NI | 2.2 |

| 25 (TED-574) | N |

|

54, 31a | ND | NI | NI | ND |

| 26 (TED-567) | CH |

|

100 | 2.0 ± 0.7, max 41% | NI | NI | 5.3 |

| 27 (RHA-404) |

|

29, 30, 30 | <1, max 50% | NI | NI | 2.8 | |

| |||||||

| R1 | |||||||

| 28 (RHA-350) |

|

52, 23 | 1.9 ± 0.6, max 50% | NI | NI | 1.7 | |

| 29 (RHA-351) | H– | 75, 25 | 3.6 ± 0.9, max 49% | NI | NI | 3.1 | |

Additional protein–compound adduct detected in the mass spectrum.

Maximum inhibition.

NI, no inhibition.

LipE = pIC50 − clog P.

Fig. 2. (A) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 2 (RHA-059) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (B) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 2 (RHA-059) for 0.5–6 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (C) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration was fit with a linear function to determine kinact/KI. (D) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 8 (RHA-363) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (E) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 8 (RHA-363) for 0.5–12 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (F) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration plot was fit with a hyperbolic function to determine kinact and KI.

Fig. 3. (A) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 13 (RHA-302) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (B) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 13 (RHA-302) for 0.5–6 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (C) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration plot was fit with a hyperbolic function to determine kinact and KI. (D) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 21 (MAT-241) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (E) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 21 (MAT-241) for 0.5–6 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (F) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration plot was fit with a hyperbolic function to determine kinact and KI.

Dihydropyrazole hit compounds

The first class of hit compounds was a set of ten dihydropyrazoles (Table 1). The compounds inhibited TEAD4 binding to YAP1 using our FP assay with single digit micromolar IC50s with maximum inhibition ranging from 39 to 67% following 24 h incubation of TEAD4 with compounds at 4 °C (Table 1 and Fig. S2A†). Under the same conditions, the compounds did not inhibit TEAD4C367S binding to YAP1 suggesting that reaction at Cys-367 is required for inhibition of the protein–protein interaction. The compounds also did not inhibit the unrelated uPAR·AE-147 interaction (Table 1 and Fig. S2A†).

Whole-protein mass spectrometry was used to confirm covalent adduct formation. After 24 h and 4 °C incubation of the protein with compound at 100 μM, all ten dihydropyrazoles formed adducts with wild-type TEAD4, but no adduct was detected for TEAD4C367S mutant (Table 1 and Fig. S2B†). Most compounds showed a single major peak and a smaller second peak (Table 1). The second peak, which corresponds to a second adduct on the same protein, is likely due to the high compound concentration and long incubation time. It is important to note that no adduct is detected in the TEAD4C367S mutant, suggesting that the second reaction likely occurs due to conformational changes introduced by the first reaction. Therefore, the second peak is not an indication of non-specific reaction of the compound, or the presence of a second binding site.

Compounds 2 (RHA-059) and 8 (RHA-363) were selected for inhibition studies in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2). The IC50 for 2 (RHA-059) improved over time from 18 μM after 30 min incubation to 1.4 μM after 48 h incubation (Fig. 2A). To gain insight into the reaction rates of the compound, time- and concentration-dependent whole protein mass spectrometry studies were carried out (Fig. 2B). TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 2 (RHA-059) and aliquots were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid at specified time points. The relative adduct formation was quantified by mass spectrometry and pseudo first-order rate constant (kobs) was determined for each concentration of 2 (RHA-059) by fitting an exponential equation. The kobs were plotted against their respective concentration to determine the second-order rate constant kinact/KI (Fig. 2C and Table 2). The kobs for 2 (RHA-059) did not plateau over the compound concentration range, and a linear function was fitted to determine a kinact/KI of 13.5 ± 0.9 M−1 s−1. A similar study was carried out for 8 (RHA-363). IC50 for inhibition of the compound improved from 24 μM at 30 min to 3 μM after 48 h incubation (Fig. 2D). The kobs of adduct formation for 8 (RHA-363) was determined (Fig. 2E) and a hyperbolic function  was fitted to determine maximum potential rate constant of adduct formation, kinact, and the binding constant KI (Fig. 2F). The kinact/KI of 8 (RHA-363) was 8.3 M−1 s−1, which is 2-fold less than that of 2 (RHA-059) due to the slower kinact (Table 2). On the other hand, the binding constant KI of 8 (RHA-363) was 37.7 μM. The reaction half-life for the compound, t∞1/2, obtained from kinact, was less than 1 hour.

was fitted to determine maximum potential rate constant of adduct formation, kinact, and the binding constant KI (Fig. 2F). The kinact/KI of 8 (RHA-363) was 8.3 M−1 s−1, which is 2-fold less than that of 2 (RHA-059) due to the slower kinact (Table 2). On the other hand, the binding constant KI of 8 (RHA-363) was 37.7 μM. The reaction half-life for the compound, t∞1/2, obtained from kinact, was less than 1 hour.

Hit compounds with peptide core

The second group of hits that emerged from the initial screen consisted of eleven compounds with a peptide core (Table 3). Ten of the eleven compounds, 11–17, and 19–21, inhibited only wild-type TEAD4 and not TEAD4C367S mutant (Table 3 and Fig. S3A†). The compounds had single-digit micromolar IC50s with maximum inhibition ranging from 31 to 67% after 24 h incubation at 4 °C. Compound 18 (RHA-013) inhibited both wild-type TEAD4 and TEAD4C367S mutant with similar double-digit micromolar IC50s. All eleven compounds did not bind to uPAR and inhibit its interaction with AE-147 peptide (Table 3 and Fig. S3A†). Ten compounds 11–17 and 19–21 were tested for covalent adduct formation by mass spectrometry (Fig. S3B† and Table 3). After 24 h incubation at 4 °C, all tested compounds formed a covalent bond with wild-type TEAD4 and not TEAD4C367S. Compounds 12 (RHA-010), 13 (RHA-302), 17 (RHA-132) and 21 (MAT-241) formed two additional peaks at 100 μM after 24 h (Table 3). It is important to note that when Cys-367 is mutated, no adduct is detected suggesting that the second reaction likely occurs due to conformational changes introduced by the first reaction at the central pocket cysteine. Therefore, the second peak is not an indication of non-specific reaction of the compound, or the presence of a second binding site.

Compounds 13 (RHA-302) and 21 (MAT-241) were selected for follow-up inhibition study in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3A and D). We included 21 (MAT-241) into the set of peptide-like series because its predicted binding mode showed that the two benzene rings of the compound generally occupy the same pockets as the R1 and R3 substituents as the peptide-like series of compounds. The compounds had improved IC50s with increasing incubation times. Compound 13 (RHA-302) inhibited with an IC50 of 10 μM at 30 min, which improved ten-fold after 48 h incubation to 0.9 μM. Compound 21 (MAT-241) did not inhibit after 30 min incubation, but inhibition improved from IC50 of 54 μM at 6 h to 5 μM after 48 h (Fig. 3D). Although the compounds had multiple adducts at 100 μM and 24 h (Table 3 and Fig. S3B†), the additional adducts were not detected at lower concentrations and shorter incubation times. These additional peaks do not suggest non-specific reaction, or the presence of a second binding site, since no adducts were detected for the mutant protein. Instead, the additional peaks are likely due to conformational changes that are induced by binding and reaction of the compound at the central pocket cysteine. Overall, the two compounds had t∞1/2 values in the 2–3 h range (Table 2). The kinact led to kinact/KI of 5.1 M−1 s−1 and 1.3 M−1 s−1 for 13 (RHA-302) and 21 (MAT-241), respectively. Compound 13 (RHA-302) had a KI of 17 μM (Table 2).

Piperazine, piperidine, and imidazolidine hit compounds

The third set of compounds that emerged from the initial screen contained piperazine, piperidine and imidazolidine scaffolds (Table 4). The eight compounds 22–29 inhibited wild-type TEAD4 and not TEAD4C367S or uPAR (Table 4 and Fig. S4A†). The compounds had IC50s from single- to double-digit micromolar ranges with maximum inhibition reaching 41 to 54% at 24 h and 4 °C (Table 4 and Fig. S4A†). Compound 27 (RHA-404) inhibited with an IC50 less than 1 μM, but mass spectrometry showed multiple adduct peaks (Fig. S4B†). The piperidine 26 (TED-567) had a 2.0 ± 0.7 μM IC50 and a single 100% adduct (Table 4). Compounds 25 (TED-574), 28 (RHA-350) and 29 (RHA-351) formed two adduct with TEAD4, but they also formed adducts with the TEAD4C367S mutant protein (Fig. S4B†).

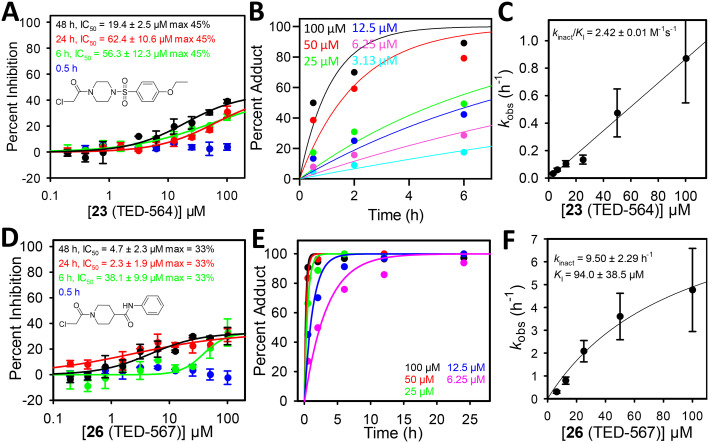

Compounds 23 (TED-564) and 26 (TED-567) were further characterized. The compounds inhibited in a time-dependent manner and the IC50s improved slightly as incubation time increased (Fig. 4A and D). Upon determination of kinact/KI (Table 2) 26 (TED-567) had the best overall second-order rate constant at 28 M−1 s−1. The compound reacted fast with t∞1/2 in minutes with KI close to 100 μM. The kobsversus concentration plot for 23 (TED-564) did not plateau and a linear function was fit to determine a kinact/KI of 2.4 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 4B and C).

Fig. 4. (A) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 23 (TED-564) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (B) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 23 (TED-564) for 0.5–24 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (C) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration was fit with a linear function to determine kinact/KI. (D) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 26 (TED-564) for 0.5–48 h at 4 °C prior to detection of binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide (n = 2). (E) TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations of 26 (TED-567) for 0.5–24 h at 4 °C. The reactions were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid and adduct formation was quantified by whole-protein mass spectrometry. Rate constant, kobs, for each concentration of compound was determined by fitting an exponential function. (F) Rate constant, kobs, versus compound concentration was fit with a hyperbolic function to determine kinact and KI.

Other fragment hits

The last set of compounds that emerged from our initial screen were covalent fragments with distinct core structures (Fig. S5A†). The fragments had IC50s in the range of 1.4 to 170 μM with maximum inhibition ranging from 35% to nearly 100% (Fig. S5B and D†). Fragments 30 (RHA-340), 31 (RHA-418) and 38 (RHA-444) inhibited wild-type TEAD4, TEAD4C367S and uPAR (Fig. S5B†) suggesting non-specific reaction; they were not characterized further. In mass spectrometry, all seven tested fragments formed robust adducts with TEAD4, but not TEAD4C367S (Fig. S5C†). Fragment 35 (HPV-071) was the only compound to form multiple adducts with wild-type TEAD4 at high concentration, though no adduct was detected for TEAD4C367S.

Fragments 36 (RHA-337) and 37 (RHA-349) were tested for inhibition in a time-dependent manner (Fig. S5E†). The IC50 of 36 (RHA-337) improved from 40 μM at 30 min incubation to 0.9 μM following 24 h incubation. The IC50 of fragment 37 (RHA-349) did not change over time, remaining at double digit micromolar from 30 min to 48 h. The rate constant of adduct formation for 36 (RHA-337) and 37 (RHA-349) showed both fragments to have a linear profile (Fig. S5F and G†). As expected for fragments, the kinact/KI values were the lowest of all the characterized compounds (Table 2).

Reaction and inhibition across all TEADs

The eight representative compounds from the four classes of hit compounds were tested for inhibition of TEAD paralogs, namely TEAD1, TEAD2 and TEAD3 (Table 5 and Fig. S6†). After 24 h incubation with individual TEADs, binding to fluorescently labeled YAP160–99 peptide was measured by fluorescence polarization. Fragment 36 (RHA-337) inhibited TEAD1 with an IC50 of 3.0 ± 0.8 μM to a maximum of 31% and fragment 37 (RHA-349) showed weak inhibition of TEAD1 at high concentration. Dihydropyrazoles 2 (RHA-059) and 8 (RHA-363) inhibited TEAD2 with single digit micromolar IC50s. Compound 21 (MAT-241) and fragment 37 (RHA-349) inhibited TEAD2 at high concentration. None of the compounds inhibited TEAD3 binding to YAP1.

Inhibition of TEAD1–3 binding to YAP160–99.

| Compound | Inhibition IC50 at 24 h 4 °C (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAD1 | TEAD2 | TEAD3 | |

| 2 (RHA-059) | NIa | 2.3 ± 0.5; maxb 29% | NI |

| 8 (RHA-363) | NI | 3.1 ± 0.3; max 35% | NI |

| 13 (RHA-302) | NI | NI | NI |

| 21 (MAT-241) | NI | 22.0 ± 3.5; max 22% | NI |

| 23 (TED-564) | NI | 46.5 ± 23.8; max 14% | NI |

| 26 (TED-567) | NI | NI | NI |

| 36 (RHA-337) | 3.0 ± 0.8; max 31% | 254 ± 53.1 | NI |

| 37 (RHA-349) | 182 ± 34.3 | 86.7 ± 4.4 | NI |

NI, no inhibition.

Maximum inhibition.

Incubating TEAD1–3 with 100 μM compounds for 24 h at 4 °C showed that all the hits reacted to the TEAD paralogs (Fig. S7 and Table S1†). All eight compounds formed adducts with TEAD1. Compound 8 (RHA-363) formed adducts of 329 Da, which did not match the expected 360 Da. This compound formed the correct 360 Da adduct with TEAD2 and TEAD4 but the adducts were 329 Da with TEAD1 and TEAD3, suggesting possible decomposition of the compound following covalent bond formation. Similarly, 21 (MAT-241) formed an adduct that corresponds to the protein–compound complex in TEAD1. An additional adduct detected by the mass difference did not correspond to the expected value of 363 Da, suggesting that the compound may have decomposed at the second reaction site. It is important to note that these additional peaks do not likely correspond to an additional binding site or lack of compound specificity as no peaks are detected when mutant TEAD4C367S is incubated with compound. For TEAD2 and TEAD4, the adducts detected correspond to the correct covalent complex with one or more compounds. Fragment 36 (RHA-337), which inhibited TEAD1 binding to YAP1, formed a single 100% adduct to TEAD1. Against TEAD2, the compounds formed multiple adducts, except for the dihydropyrazole 8 (RHA-363), which formed a single reaction adduct to TEAD2 and inhibits TEAD2 with an IC50 of 3.1 ± 0.3 μM (Table 5). Despite not showing any inhibition, all eight compounds formed robust reaction adduct with TEAD3.

Binding pose hypotheses from covalent docking

Covalent molecular docking was used to provide potential binding modes for fragments and compounds from each class that were further characterized with time- and concentration-dependent studies. The palmitate binding pocket can be divided into three sub-sites: lower, middle, and upper (Fig. 5A). In TEAD4, the middle sub-site is hydrophobic and consists of aromatic residues Phe-229, Phe-393 and Tyr-413 as well as hydrophobic residues Met-370, Ile-395, Leu-366, Val-316, and Ala-231 (Fig. 5B). The lower sub-site is delineated by aromatic residues Phe-247, Phe-415, and hydrophobic residues Val-248, Leu-302, Ile-374, Leu-377 and Leu-390. The upper sub-site is not involved in binding to fatty acids, but we have shown previously that small-molecule inhibitors can take advantage of this additional pocket.1a,10 This upper sub-site is less hydrophobic than the lower and middle pockets; the upper site residues include Cys-330, Thr-332, Gln-397, Lys-344, Val-316, Phe-229 and Glu-346, which are less hydrophobic compared to the other sub-sites.

Fig. 5. (A) Stereoview of the central pocket of TEAD4 in covalent complex with myristate (PDB: 5OAQ). TEAD4 central pocket is shown in gray Connolly surface representation and myristate in capped-sticks representation with yellow carbons and red oxygen. Sub-sites within the pocket are highlighted in dashed boxes. (B) Stereoview of the central pocket of TEAD4 (gray ribbon representation) in covalent complex with myristate (capped sticks representation with yellow carbons and red oxygen). TEAD4 residues that surround the pocket are represented as capped-sticks with carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur in green, red, blue and gold, respectively. Covalent molecular docking poses are shown in stereoview. TEAD4 central pocket is shown in gray Connolly surface representation. Docked compound is in capped-sticks representation with carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, chlorine and fluorine in yellow, red, blue, gold, green and cyan, respectively. Sub-sites within the pocket are highlighted in dashed boxes. (C) 2 (RHA-059), (D) 8 (RHA-363), (E) 13 (RHA-302), (F) 21 (MAT-241), (G) 23 (TED-564), (H) 26 (TED-567), (I) 36 (RHA-337), (J) 37 (RHA-349).

Docking models for the dihydropyrazoles 2 (RHA-059) and 8 (MAT-363) suggest that each of the three rings of the compounds occupies one of the three sub-sites (Fig. 5C and D). The dihydropyrazole moiety is in the middle sub-site, and the substituent at the 3-position points into the lower sub-site, while the substituent at the 5-position points to the upper sub-site. The toluoyl moiety of 2 (RHA-059) and the thiophene of 8 (RHA-363) partially occupy the lower sub-site. The furan of 2 (RHA-059) is smaller and does not fully occupy the upper sub-site, while the dimethoxyphenyl of 8 (RHA-363) binds to more of the sub-site. However, it requires more changes around the conformation of the residues in the upper sub-site.

The docking binding modes of peptide-like 13 (RHA-302) shows that the compound fully engages all three sub-sites in the palmitate pocket (Fig. 5E). The chlorophenyl, thiophene and phenethyl moieties bind to the upper, middle, and lower sub-sites, respectively. The longer phenethyl moiety mimics the aliphatic chain of the fatty acid. It is to note that the compound has the best KI among the tested hits, namely 17 μM (Table 2). The docking model of 21 (MAT-241) suggests that this compound may fully engage all three sub-sites (Fig. 5F). The upper sub-site is occupied by the fluorobenzyl moiety, and the middle and lower sub-sites are occupied by the phenyl ethanesulfonate.

The docking binding modes of piperazine 23 (TED-564) and piperidine 26 (TED-567) show that the compounds bind into the middle and lower sub-sites, without interacting with the upper sub-site (Fig. 5G and H). The hydrophilic sulfonamide of 23 (TED-564) and the amide of 26 (TED-567) may not be ideal for the highly hydrophobic middle and lower sub-sites. This and the lack of interaction in the upper sub-site may explain weaker KIs (Table 2). However, the rate of reaction is fast for this set of compounds, likely due to better positioning of the reactive warhead relative to the thiol moiety of the conserved cysteine. In addition, 23 (TED-564) and 26 (TED-567) mimic the native fatty acid well and likely does not require conformational shifts of the amino acids surrounding the palmitate pocket.

The docking binding pose for fragment 36 (RHA-337) suggests that the benzofuran moiety only occupies the middle sub-site and the carboxamide at the 2-position of the fragment points toward the upper sub-site (Fig. 5I). Fragment 37 (RHA-349) is flexible and largely linear. The docking model shows the compound binds to the middle and lower pockets. The linear compound mimics the binding mode of palmitate as it occupies the same binding site as the aliphatic chain of fatty acid (Fig. 5J).

Discussion

There is substantial interest in small-molecule antagonists of the TEAD·YAP/TAZ transcriptional complex considering its role in cancer and other pathological processes. The main motivation behind this work is to identify new scaffolds for the development of small-molecule inhibitors of the TEAD·YAP1 protein–protein interaction using the palmitate binding pocket. To date, the only two examples of small molecules that bind to the palmitate pocket that also inhibit YAP1 binding to TEAD are our original covalent inhibitor, TED-347, and a recent compound reported by Genentech.14 However, their compound is not a covalent inhibitor. The overwhelming majority of small molecules that bind to the palmitate pocket are developed to inhibit palmitate binding, not the interaction between TEAD and YAP1. Although Novartis has recently developed orthosteric inhibitors of TEAD binding to YAP1, it will be highly challenging to develop these into therapeutic agents considering the lack of a druggable pocket at the TEAD·YAP1 protein–protein interface.15 Chène and coworkers also developed orthosteric inhibitors, but their compounds are peptidomimetics.16

Considering the high affinity of the TEAD·YAP/TAZ interaction, as well as the large interface that is devoid of druggable pockets, we recently proposed an alternative strategy that took advantage of the presence of a cysteine residue within a deep palmitate pocket present in TEADs.1a We designed TED-347 to form a covalent bond with the conserved cysteine in the palmitate pocket and discovered that the compound inhibited TEAD4 binding to YAP1. Since the palmitate pocket is located outside the protein–protein interaction interface, the inhibition mechanism is likely allosteric. Our chloromethyl ketone compounds were designed based on the structure of the drug flufenamic acid bound to TEAD2, which had no effect on TEAD binding to YAP1.17 More recently, we used flufenamic acid as an inspiration to design new covalent inhibitors with a cyanamide warhead. These compounds, such as TED-642, reacted far more rapidly to TEADs with reaction half-lives in the minutes compared to hours for TED-347.

Here, we screen a library of chloroacetamide fragments to uncover novel scaffolds that could be used for the development of covalent inhibitors of TEAD palmitoylation and binding to YAP1. To give insight into the diversity of the library, we used hierarchical clustering using a Tanimoto coefficient cut-off of 0.7, which resulted in 139 clusters. The first set of 10 dihydropyrazoles were found in two clusters with a combined 39 compounds, all dihydropyrazoles. The peptide-like series were found in the largest cluster with 192 compounds. The third set compounds containing piperazines, piperidines and imidazolidines were found in clusters with 14, 4 and 5 compounds, respectively. Two unique structures, compounds 21 (MAT-241) and 27 (RHA-404), were found in clusters with 2 and 1 compounds, respectively. Several fragments and small molecules were found to inhibit TEAD4 binding to the YAP1 peptide. We confirmed that the inhibition was due to covalent bond formation by repeating the same inhibition studies with the mutant TEAD4C367S. The specificity toward the cysteine was further confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Time-dependent mass spectrometry showed that hits such as 2 (RHA-059) and 26 (TED-567) reacted to TEAD4 rapidly with kinact/KI double-digit M−1 s−1 range. The peptide-like compounds 13 (RHA-302) and 21 (MAT-241) had micromolar KI values. Compound 21 (MAT-241) lacks the R3 aromatic moiety compared to 13 (RHA-302) and has 3-fold higher KI. However, 21 (MAT-241) highlights the potential for further development of this structure. The fragments 36 (RHA-337) and 37 (RHA-349) had weak kinact/KI, which is expected for small fragments with low molecular complexity and likely form limited interactions within the pocket.

The representative dihydropyrazoles 2 (RHA-059) and 8 (RHA-363) inhibited TEAD4 and TEAD2. TEAD1 was only inhibited by fragment 36 (RHA-337), which formed a single complete adduct toward TEAD1. The robust reaction to TEADs and the inhibition observed against TEAD1 and TEAD4 suggests the fragment could be developed further. The peptide-like compounds 13 (RHA-302) and 21 (MAT-241), the piperazine 23 (TED-564) and the piperidine 26 (TED-567) did not inhibit TEAD1–3 binding to YAP1 significantly, although they formed covalent adducts. Compound 26 (TED-567) inhibited TEAD4 with 2 μM IC50 and its kinact/KI was 28 M−1 s−1. Further optimization could improve the kinact/KI. As the initial screen targeted TEAD4, the compound hits may have been selected for TEAD4 inhibitors. It is likely that an initial screen against TEAD3 results in compounds that inhibit TEAD3 over other TEADs. The compound structures that emerged from our work are distinct from existing small molecules that bind to the palmitate pocket (Fig. S8†).

It is important to note that chloroacetamides are likely not suitable for the development of therapeutic agents. It is worth noting, however, that several chloroacetamide compounds have been shown to be efficacious in vivo18 including the recent development of sulfopin, a covalent inhibitor of Pin1, by Gray and London.19 Others have shown that the chloroacetamide warhead can become more stable with certain moieties placed at the α-position such as 2-chloropropiolamide20 and fluorochloracetamide.21 Ojida and co-workers introduced a fluorine at the α-position on a chloroacetamide to produce a less reactive warhead with substantially greater selectivity and in vivo stability.22 Beyond chloroacetamides, it is conceivable that other warheads such as acrylamides or cyanamides as we recently reported instead of the chloroacetamides on our compound scaffolds may form a covalent bond at the conserved cysteine. Recently, Gray and co-workers published a new class of small-molecule acrylamide covalent inhibitors of TEAD palmitoylation.23

We resorted to covalent docking to provide potential binding modes for the fragments and inform future efforts to enhance the binding affinity and reaction rates of compounds. The purpose of docking is to generate hypotheses to guide future hit-to-lead optimization efforts. Molecular docking has the potential to generate incorrect binding poses, and ideally, experimental data is required to validate these poses. The palmitate pocket was divided into three sections, lower, middle, and upper sub-sites. The upper site is located near the entrance of the palmitate pocket, while the lower and middle sub-sites are located deeper into the pocket. Palmitate primarily engages these two sites. Compounds from two of the hit clusters identified in this work engaged all three sub-sites as illustrated by the binding poses of dihydropyrazoles 2 (RHA-059) and 8 (RHA-363), and peptide-mimicking 13 (RHA-302) and 21 (MAT-241). The latter compounds showed the most optimal engagement of the subsites, possibly explaining their more favorable KI values. Other fragments with a linear shape, such as 23 (TED-564), 26 (TED-567), 37 (RHA-349), mimicked the binding pose of the aliphatic chain of palmitate.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

TEAD4 (residues 217–434) and TEAD4C367S were cloned into pGEX-6P-1 vector and expressed as a glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Cell culture was grown in lysogeny broth (LB) and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) at OD600 of 0.6 and the protein was expressed at 16 °C overnight. Cells were resuspended in 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and lysed by microfluidizer. Protein was bound and purified on a 5 mL GSTrap HP column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) and eluted with lysis buffer supplemented with 10 mM reduced glutathione. Fractions containing GST-TEAD4 were further purified on HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 200 pg SEC column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) using a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT. The GST tag was cleaved by human rhinovirus (HRV)-3C enzyme (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) for 48 h at 4 °C. The cleavage reaction was re-purified on GSTrap HP to remove the tag.

TEAD1 (residues 209–426) was cloned into pET-28a-TEV vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in LB. Cell culture was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at 16 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 2× PBS, lysed by microfluidizer, and clarified by centrifugation. The clarified lysate was loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) pre-equilibrated with 2× PBS and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME). After 20 column volume (CV) wash with 2× PBS with 2 mM BME, the protein was eluted by a linear gradient, from 0 to 500 mM imidazole in 2× PBS. The fractions containing TEAD1 were pooled and treated with fresh 6 mM hydroxylamine for 3 h at room temperature (RT) to remove the covalently bound fatty acids. The sample was further purified on HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) using PBS with 2 mM DTT.

TEAD2 (residues 217–447) was cloned into pET-28a-TEV vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in terrific broth (TB). Cell culture was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at 16 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in a buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM TCEP, lysed by microfluidizer and clarified by centrifugation. The lysate was loaded onto a 1 mL PureCube 100 Ni-INDIGO column (Cube Biotech, Monheim, Germany) pre-equilibrated in buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5% v/v glycerol, 30 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP. After 20 CV wash with buffer, the protein was eluted in 15 CV of 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5% v/v glycerol, 300 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP. Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease was added at a ratio of 50 : 1 w/w and the mixture was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against 1 L 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5% v/v glycerol, 1 mM TCEP. The cleaved product was passed over the PureCube 100 Ni-INDIGO column and the flow-through containing the untagged TEAD2 was collected. The protein was treated with fresh hydroxylamine and purified on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) using 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 1 mM TCEP.

TEAD3 (residues 210–427) was cloned into pET-28a-TEV vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in TB. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in a buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaPi pH 7.8, 2 mM BME, lysed by microfluidizer and clarified by centrifugation. The clarified lysate was loaded onto 5 mL HisTrap HP column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA), washed with 20 CV lysis buffer, and eluted with linear gradient from lysis buffer to a buffer containing 1 M NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 2 mM BME, pH 6.5. The fractions containing TEAD3 were pooled, treated with 6 mM hydroxylamine for 3 h at RT, and purified on HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) using PBS with 2 mM DTT.

uPAR lacking the GPI anchor was expressed in S2 cells and purified as described previously.24 The cells were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to clarify the supernatant. After removing cells, 0.1 volume of 200 mM EDTA, 0.1% w/v sodium azide, 1 M Tris pH 8.0 as well as 0.005 volume of 200 mM PMSF in DMSO was added to the supernatant. The sample was filtered on a 0.22-micron filter prior to being injected onto a column containing Sepharose-4B beads conjugated with AE152 peptide, pre-equilibrated with wash buffer (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.4). The column was washed with 10 column volume of wash buffer until a stable baseline was achieved. The protein was eluted with the multiple cycling of wash buffer and elution buffer (0.1 M CH3COOH, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 3.0) until all the protein was eluted. Elution fractions were neutralized immediately with 1 M Tris-base, pH 11. The protein fractions were further purified via size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 pg, GE Healthcare) in PBS.

Fluorescence polarization binding assay

TEAD1–4 interaction with YAP1 was investigated using a FAM-labeled TEAD-binding domain of YAP1, residues 60–99, (FAM-DSETDLEALFNAVMNPKTANVPQTVPMCLRKLPASFCKPP). The peptide was engineered with a disulfide cross-link. The assay was conducted in a 384-well black polystyrene plate (cat. no. 262260; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in PBS with 0.01% Triton X-100. Compounds in a 5 μL mixture of assay buffer and 20% v/v DMSO were added and incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with 40 μL TEAD samples. The final concentrations of TEADs were 250 nM TEAD1, 64 nM TEAD2, 64 nM TEAD3, 64 nM TEAD4 and 64 nM TEAD4C367S. After compound incubation, 5 μL of fluorescent peptide was added and the fluorescence polarization was measured on an Envision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) using a filter set with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 535 nm, respectively. The final concentration of peptide was 16 nM for all assays. Percent inhibition was calculated relative to the maximum polarization control (no compound) and minimum polarization control (no TEAD4).

For the inhibition of uPAR·AE-147 interaction, same experimental setup was followed with final concentrations of 250 nM uPAR and 100 nM AE-147-FAM peptide.

For time-dependent inhibition assay with TEAD4, the compounds were incubated for 0.5, 6, 24 and 48 h at 4 °C in assay plates with TEAD4 prior to the addition of the fluorescent peptide.

Whole-protein mass spectrometry

Compounds at 100 μM concentrations were incubated with 2.5 μM TEAD1–4 or TEAD4C367S mutant in PBS for 24 h at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 20 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove precipitants prior to being injected into a Zorbax 300-SB C3 column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) on an Agilent 1200 liquid chromatography system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Buffer salts were separated from the protein sample using a gradient of buffer A (H2O with 0.1% formic acid) and buffer B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid), and the masses were detected on an Agilent 6520 Accurate Mass Q-TOF (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

For the determination of the maximum potential rate of covalent bond formation kinact and the binding constant KI, 2.5 μM TEAD4 was incubated with varying concentrations (3.1–100 μM) of compounds at 4 °C. Aliquots from the incubations were quenched with 0.1 M formic acid at specified times and analyzed by mass spectrometry as above.

The compound adduct peak relative to the unreacted TEAD4 peak was plotted against time for all concentrations of the compound, and the observed pseudo-first order rate constant of reaction (kobs) was determined by fitting an exponential function Percent Adduct = 100 × (1 − e−kobs×time). The kobs values were plotted against their respective compound concentrations, and a hyperbolic function  was fit to determine the kinact and KI values. When the kobsversus compound concentration plot did not reach a plateau, the second-order rate constant kinact/KI was determined by fitting a linear function.

was fit to determine the kinact and KI values. When the kobsversus compound concentration plot did not reach a plateau, the second-order rate constant kinact/KI was determined by fitting a linear function.

Molecular docking

Covalent docking of compounds to TEADs was carried out using the CovDock approach implemented in the Schrodinger suite of programs (CovDock, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2023). The three-dimensional structure of TEAD1 (PDB code: 4RE1), TEAD2 (PDB code: 6E5G), and TEAD3 (PDB code: 5EMW) were downloaded from the Protein Databank directly from the Maestro graphical user interface. The crystal structure of TEAD4 was obtained from the structure of a TEAD4·YAP1 solved in our laboratory from crystals of TEAD4 grown in complex with a YAP1 peptide. All structures were prepared for docking using the Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2023). This consisted of first reviewing each structure to identify ligands, metals, ions, or other molecules. The structures were preprocessed such as bond orders were assigned, hydrogen atoms replaced, disulfide bonds defined, and short missing loops added. The structures were further prepared by identifying missing or overlapping sidechains, and alternative structures for side chains that are generated during the refinement process. All solvent molecules were deleted from the structures. Hydrogen bond assignments were optimized using ProPKA, followed by energy minimization of each structure as the final step before covalent docking. Prior to covalent docking, small molecules are prepared using the LigPrep module within Maestro (LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2023). The ionization state of ionizable groups were determined using Epik for a pKa range of 7 ± 1. All salts are removed from structures and all tautomers were generated. For chiral centers, all combinations were generated.

The covalent docking is carried out using the Covalent Docking module in Maestro based on the CovDock approach. First, the reactive residue is defined as the conserved cysteine in the palmitate binding pocket of each structure. This is followed by the definition of the enclosing box that is used to focus the molecular docking. The box is created by using the centroid of selected residues. The reaction type is selected as Michael addition. Finally, the minimization radius during docking was set to 12 angstroms, along with default settings for cutoff to retain poses for further refinement.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs (I01BX005188) [SOM], National Institutes of Health (R01CA264471) [SOM]. The research was supported by an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-12-092-01-CDD (SOM), Vera Bradley Foundation fellowship (KB), Vera Bradley Foundation grant (SOM), Indiana University Simon Cancer Center Near Miss Initiative grant (SOM), and the 100 Voices of Hope (SOM).

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3md00264k

References

- (a) Bum-Erdene K. Zhou D. Gonzalez-Gutierrez G. Ghozayel M. K. Si Y. Xu D. Shannon H. E. Bailey B. J. Corson T. W. Pollok K. E. Wells C. D. Meroueh S. O. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019;26:378–389 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mesrouze Y. Meyerhofer M. Bokhovchuk F. Fontana P. Zimmermann C. Martin T. Delaunay C. Izaac A. Kallen J. Schmelzle T. Erdmann D. Chène P. Protein Sci. 2017;26:2399–2409. doi: 10.1002/pro.3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Galli G. G. Carrara M. Yuan W.-C. Valdes-Quezada C. Gurung B. Pepe-Mooney B. Zhang T. Geeven G. Gray N. S. de Laat W. Calogero R. A. Camargo F. D. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oh H. Slattery M. Ma L. Crofts A. White K. P. Mann R. S. Irvine K. D. Cell Rep. 2013;3:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhao B. Ye X. Yu J. Li L. Li W. Li S. Yu J. Lin J. D. Wang C. Y. Chinnaiyan A. M. Lai Z. C. Guan K. L. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J. Smolen G. A. Haber D. A. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2789–2794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhao B. Li L. Tumaneng K. Wang C. Y. Guan K. L. Genes Dev. 2010;24:72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao B. Wei X. Li W. Udan R. S. Yang Q. Kim J. Xie J. Ikenoue T. Yu J. Li L. Zheng P. Ye K. Chinnaiyan A. Halder G. Lai Z. C. Guan K. L. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Park H. W. Kim Y. C. Yu B. Moroishi T. Mo J.-S. Plouffe S. W. Meng Z. Lin K. C. Yu F.-X. Alexander C. M. Wang C.-Y. Guan K.-L. Cell. 2015;162:780–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seo E. Basu-Roy U. Gunaratne P. H. Coarfa C. Lim D.-S. Basilico C. Mansukhani A. Cell Rep. 2013;3:2075–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee D.-H. Park J. O. Kim T.-S. Kim S.-K. Kim T.-H. Kim M.-C. Park G. S. Kim J.-H. Kuninaka S. Olson E. N. Saya H. Kim S.-Y. Lee H. Lim D.-S. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11961. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lai D. Yang X. Cell. Signalling. 2013;25:1720–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang J. Ji J.-Y. Yu M. Overholtzer M. Smolen G. A. Wang R. Brugge J. S. Dyson N. J. Haber D. A. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1444–1450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Song S. Honjo S. Jin J. Chang S.-S. Scott A. W. Chen Q. Kalhor N. Correa A. M. Hofstetter W. L. Albarracin C. T. Wu T.-T. Johnson R. L. Hung M.-C. Ajani J. A. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:2580–2590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Feng J. Yang H. Zhang Y. Wei H. Zhu Z. Zhu B. Yang M. Cao W. Wang L. Wu Z. Oncogene. 2017;36:5829–5839. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kim M. H. Kim C. G. Kim S. K. Shin S. J. Choe E. A. Park S. H. Shin E. C. Kim J. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018;6:255–266. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Miao J. Hsu P. C. Yang Y. L. Xu Z. Dai Y. Wang Y. Chan G. Huang Z. Hu B. Li H. Jablons D. M. You L. Oncotarget. 2017;8:114576–114587. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Neto-Silva R. M. de Beco S. Johnston L. A. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:507–520. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Rajbhandari P. Lopez G. Capdevila C. Salvatori B. Yu J. Rodriguez-Barrueco R. Martinez D. Yarmarkovich M. Weichert-Leahey N. Abraham B. J. Alvarez M. J. Iyer A. Harenza J. L. Oldridge D. De Preter K. Koster J. Asgharzadeh S. Seeger R. C. Wei J. S. Khan J. Vandesompele J. Mestdagh P. Versteeg R. Look A. T. Young R. A. Iavarone A. Lasorella A. Silva J. M. Maris J. M. Califano A. Cancer Discovery. 2018;8:582–599. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Li Z. Zhao B. Wang P. Chen F. Dong Z. Yang H. Guan K.-L. Xu Y. Genes Dev. 2010;24:235–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.1865810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tian W. Yu J. Tomchick D. R. Pan D. Luo X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7293–7298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000293107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesrouze Y. Bokhovchuk F. Meyerhofer M. Fontana P. Zimmermann C. Martin T. Delaunay C. Erdmann D. Schmelzle T. Chene P. eLife. 2017;6:e25068. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. Han X. Zheng B. DeRan M. Yu J. Jarugumilli G. K. Deng H. Pan D. Luo X. Wu X. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Noland C, L. Gierke S. Schnier P. D. Murray J. Sandoval W. N. Sagolla M. Dey A. Hannoush R. N. Fairbrother W. J. Cunningham C. N. Structure. 2016;24:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chan P. Han X. Zheng B. DeRan M. Yu J. Jarugumilli G. K. Deng H. Pan D. Luo X. Wu X. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12(4):282–289. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bum-Erdene K. Yeh I. J. Gonzalez-Gutierrez G. Ghozayel M. K. Pollok K. Meroueh S. O. J. Med. Chem. 2023;66:266–284. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Fan M. Lu W. Che J. Kwiatkowski N. P. Gao Y. Seo H.-S. Ficarro S. B. Gokhale P. C. Liu Y. Geffken E. A. Lakhani J. Song K. Kuljanin M. Ji W. Jiang J. He Z. Tse J. Boghossian A. S. Rees M. G. Ronan M. M. Roth J. A. Mancias J. D. Marto J. A. Dhe-Paganon S. Zhang T. Gray N. S. eLife. 2022;11:e78810. doi: 10.7554/eLife.78810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karatas H. Akbarzadeh M. Adihou H. Hahne G. Pobbati A. V. Yihui Ng E. Guéret S. M. Sievers S. Pahl A. Metz M. Zinken S. Dötsch L. Nowak C. Thavam S. Friese A. Kang C. Hong W. Waldmann H. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:11972–11989. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lu W. Wang J. Li Y. Tao H. Xiong H. Lian F. Gao J. Ma H. Lu T. Zhang D. Ye X. Ding H. Yue L. Zhang Y. Tang H. Zhang N. Yang Y. Jiang H. Chen K. Zhou B. Luo C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;184:111767. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Heinrich T. Peterson C. Schneider R. Garg S. Schwarz D. Gunera J. Seshire A. Kötzner L. Schlesiger S. Musil D. Schilke H. Doerfel B. Diehl P. Böpple P. Lemos A. R. Sousa P. M. F. Freire F. Bandeiras T. M. Carswell E. Pearson N. Sirohi S. Hooker M. Trivier E. Broome R. Balsiger A. Crowden A. Dillon C. Wienke D. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65:9206–9229. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holden J. K. Crawford J. J. Noland C. L. Schmidt S. Zbieg J. R. Lacap J. A. Zang R. Miller G. M. Zhang Y. Beroza P. Reja R. Lee W. Tom J. Y. K. Fong R. Steffek M. Clausen S. Hagenbeek T. J. Hu T. Zhou Z. Shen H. C. Cunningham C. N. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107809. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu L. Sun Y. Liu S. Erb H. Singh A. Mao J. Luo X. Wu X. eLife. 2022;11:e80210. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kaneda A. Seike T. Danjo T. Nakajima T. Otsubo N. Yamaguchi D. Tsuji Y. Hamaguchi K. Yasunaga M. Nishiya Y. Suzuki M. Saito J. I. Yatsunami R. Nakamura S. Sekido Y. Mori K. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020;10:4399–4415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Melin L. Abdullayev S. Fnaiche A. Vu V. Gonzalez Suarez N. Zeng H. Szewczyk M. M. Li F. Senisterra G. Allali-Hassani A. Chau I. Dong A. Woo S. Annabi B. Halabelian L. LaPlante S. R. Vedadi M. Barsyte-Lovejoy D. Santhakumar V. Gagnon A. ChemMedChem. 2021;16:2982–3002. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas P. Le Du M. H. Gårdsvoll H. Danø K. Ploug M. Gilquin B. Stura E. A. Ménez A. EMBO J. 2005;24:1655–1663. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenbeek T. J. Zbieg J. R. Hafner M. Mroue R. Lacap J. A. Sodir N. M. Noland C. L. Afghani S. Kishore A. Bhat K. P. Yao X. Schmidt S. Clausen S. Steffek M. Lee W. Beroza P. Martin S. Lin E. Fong R. Di Lello P. Kubala M. H. Yang M. N. Lau J. T. Chan E. Arrazate A. An L. Levy E. Lorenzo M. N. Lee H. J. Pham T. H. Modrusan Z. Zang R. Chen Y. C. Kabza M. Ahmed M. Li J. Chang M. T. Maddalo D. Evangelista M. Ye X. Crawford J. J. Dey A. Nat. Cancer. 2023;4:812–828. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00577-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Sellner H. Chapeau E. Furet P. Voegtle M. Salem B. Le Douget M. Bordas V. Groell J.-M. Le Goff A.-L. Rouzet C. Wietlisbach T. Zimmermann T. McKenna J. Brocklehurst C. E. Chène P. Wartmann M. Scheufler C. Kallen J. Williams G. Harlfinger S. Traebert M. Dumotier B. M. Schmelzle T. Soldermann N. ChemMedChem. 2023;18:e202300051. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202300051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furet P. Bordas V. Le Douget M. Salem B. Mesrouze Y. Imbach-Weese P. Sellner H. Voegtle M. Soldermann N. Chapeau E. Wartmann M. Scheufler C. Fernandez C. Kallen J. Guagnano V. Chène P. Schmelzle T. ChemMedChem. 2022;17:e202200303. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesrouze Y. Gubler H. Villard F. Boesch R. Ottl J. Kallen J. Reid P. C. Scheufler C. Marzinzik A. L. Chène P. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023;18:643–651. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.2c00936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobbati A. V. Han X. Hung A. W. Weiguang S. Huda N. Chen G.-Y. Kang C. Chia C. S. B. Luo X. Hong W. Poulsen A. Structure. 2015;23:2076–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Roberts A. M. Miyamoto D. K. Huffman T. R. Bateman L. A. Ives A. N. Akopian D. Heslin M. J. Contreras C. M. Rape M. Skibola C. F. Nomura D. K. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:899–904. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fontan L. Yang C. Kabaleeswaran V. Volpon L. Osborne M. J. Beltran E. Garcia M. Cerchietti L. Shaknovich R. Yang S. N. Fang F. Gascoyne R. D. Martinez-Climent J. A. Glickman J. F. Borden K. Wu H. Melnick A. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubiella C. Pinch B. J. Koikawa K. Zaidman D. Poon E. Manz T. D. Nabet B. He S. Resnick E. Rogel A. Langer E. M. Daniel C. J. Seo H.-S. Chen Y. Adelmant G. Sharifzadeh S. Ficarro S. B. Jamin Y. da Costa B. M. Zimmerman M. W. Lian X. Kibe S. Kozono S. Doctor Z. M. Browne C. M. Yang A. Stoler-Barak L. Shan R. B. Vangos N. E. Geffken E. A. Oren R. Koide E. Sidi S. Shulman Z. Wang C. Marto J. A. Dhe-Paganon S. Look T. Zhou X. Z. Lu K. P. Sears R. C. Chesler L. Gray N. S. London N. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021;17:954–963. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allimuthu D. Adams D. J. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:2124–2131. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M. Fuchida H. Shindo N. Kuwata K. Tokunaga K. Xiao-Lin G. Inamori R. Hosokawa K. Watari K. Shibata T. Matsunaga N. Koyanagi S. Ohdo S. Ono M. Ojida A. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:1137–1144. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo N. Fuchida H. Sato M. Watari K. Shibata T. Kuwata K. Miura C. Okamoto K. Hatsuyama Y. Tokunaga K. Sakamoto S. Morimoto S. Abe Y. Shiroishi M. Caaveiro J. M. M. Ueda T. Tamura T. Matsunaga N. Nakao T. Koyanagi S. Ohdo S. Yamaguchi Y. Hamachi I. Ono M. Ojida A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:250–258. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. Fan M. Ji W. Tse J. You I. Ficarro S. B. Tavares I. Che J. Kim A. Y. Zhu X. Boghossian A. Rees M. G. Ronan M. M. Roth J. A. Hinshaw S. M. Nabet B. Corsello S. M. Kwiatkowski N. Marto J. A. Zhang T. Gray N. S. J. Med. Chem. 2023;66:4617–4632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen B. Gårdsvoll H. Juhl Funch G. Østergaard S. Barkholt V. Ploug M. Protein Expression Purif. 2007;52:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.