Abstract

Background and aims:

Elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) might have a higher risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. To investigate this, we compared the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and its subtypes, as well as ischemic stroke, in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) compared with warfarin in a real-world setting. We also determined the baseline characteristics associated with both ICH and ischemic stroke.

Methods:

Patients aged ⩾ 75 years with documented NVAF enrolled in the prospective, multicenter, observational All Nippon Atrial Fibrillation in the Elderly Registry between October 2016 and January 2018 were evaluated. The co-primary endpoints were the incidence of ischemic stroke and ICH. Secondary endpoints included subtypes of ICH.

Results:

Of 32,275 patients (13,793 women; median age, 81.0 years) analyzed, 21,585 (66.9%) were taking DOACs and 8233 (25.5%) were taking warfarin. During the median 1.88-year follow-up, 743 patients (1.24/100 person-years) developed ischemic stroke and 453 (0.75/100 person-years) developed ICH (intracerebral hemorrhage, 189; subarachnoid hemorrhage, 72; subdural/epidural hemorrhage, 190; unknown subtype, 2). The incidence of ischemic stroke (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70–0.97), ICH (aHR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55–0.83), and subdural/epidural hemorrhage (aHR 0.53, 95% CI 0.39–0.72) was lower in DOAC users versus warfarin users. The incidence of fatal ICH and fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage was also lower in DOAC users versus warfarin users. Several baseline characteristics other than anticoagulants were also associated with the incidence of the endpoints. Of these, history of cerebrovascular disease (aHR 2.39, 95% CI 2.05–2.78), persistent NVAF, (aHR 1.90, 95% CI 1.53–2.36), and long-standing persistent/permanent NVAF (aHR 1.92, 95% CI 1.60–2.30) was strongly associated with ischemic stroke; severe hepatic disease (aHR 2.67, 95% CI 1.46–4.88) was strongly associated with overall ICH; and history of fall within 1 year was strongly associated with both overall ICH (aHR 2.29, 95% CI 1.76–2.97) and subdural/epidural hemorrhage (aHR 2.90, 95% CI 1.99–4.23).

Conclusion:

Patients aged ⩾ 75 years with NVAF taking DOACs had lower risks of ischemic stroke, ICH, and subdural/epidural hemorrhage than those taking warfarin. Fall was strongly associated with the risks of intracranial and subdural/epidural hemorrhage.

Data access statement:

The individual de-identified participant data and study protocol will be shared for up to 36 months after the publication of the article. Access criteria for data sharing (including requests) will be decided on by a committee led by Daiichi Sankyo. To gain access, those requesting data access will need to sign a data access agreement. Requests should be directed to yamt-tky@umin.ac.jp.

Keywords: Age, anticoagulation, cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, stroke

Introduction

Oral anticoagulants (OACs) can effectively reduce the risk of stroke and embolic events in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), 1 and global guidelines recommend stroke prevention using OACs, preferentially direct OACs (DOACs), due to their lower bleeding risk compared with warfarin.2–5 Retrospective European studies have observed a decline in AF-related stroke rates associated with high DOAC uptake.6–8

The incidence of AF has increased with global aging. In the European Union, it is estimated that the percentage of patients with AF aged ⩾ 65 years will increase by 89% from ~7.6 million in 2016 to ~14.4 million in 2060. 9 It is currently unknown whether DOACs are similarly effective and safe for elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who generally have more risk factors for stroke and bleeding than the younger population. Japan has one of the largest and fastest growing aging populations in the world. Data from Japan regarding the clinical practices applied to the increasing elderly population with NVAF can aid other regions undergoing similar aging population growth. Thus, we designed the All Nippon AF In Elderly (ANAFIE) Registry, a nationwide, prospective study of patients with NVAF aged ⩾ 75 years.10,11 In this world’s largest registry of elderly patients with NVAF (> 30,000), two-thirds of the population were receiving DOACs, which was significantly associated with a lower rate of stroke/systemic embolism, major bleeding, and all-cause death compared with well-controlled warfarin. 12 These results were generally similar to those of several meta-analyses of large-scale studies on patients aged ⩾ 75 years with NVAF.13–15

However, previous studies generally focused on overall stroke, or ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke at most, as an endpoint event. Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is classified into subtypes, each with a completely different pathophysiology: intracerebral, subarachnoid, subdural, and epidural hemorrhage. In addition, the clinical severity of stroke can vary from very mild stroke to disabling or fatal stroke.

Aims

In the present subanalysis of the ANAFIE Registry, we determined the incidence of ICH and its subtypes, as well as ischemic stroke, by anticoagulation strategy in elderly patients with NVAF. Patients who died, those who were not directly discharged home, and those who needed surgical interventions were regarded as severely disabled stroke patients, and their incidences were also determined. Baseline characteristics associated with each endpoint were also clarified.

Methods

Study design and population

The ANAFIE Registry (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000024006) is a prospective, multicenter, observational study of elderly Japanese patients with NVAF. The full study design was published in Supplemental materials.10–12 Briefly, all participants were registered from 1273 medical institutions throughout Japan between October 2016 and January 2018 and followed up for 2 years. Data were collected at baseline and at 1 and 2 years. Patients were censored when primary and secondary endpoints occurred. Ethics committee approvals were obtained from each institution (Cardiovascular Institute Ethics Committee, Approval No. 299). The study complied with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, the research protocol was approved by locally appointed ethics committees, and all patients, or their legally authorized representatives, provided informed consent at the time of enrollment.

The ANAFIE Registry enrolled both men and women aged ⩾ 75 years at the time of registration, with AF identified by chest 12-lead electrocardiogram, and who were able to attend follow-up visits. Excluded patients were those currently participating or planning to participate in an interventional study; with a definitive diagnosis of mitral stenosis; history of artificial heart valve replacement; recent history of cardiovascular events, or any bleeding leading to hospitalization within 1 month prior to enrollment; life expectancy < 1 year; and those whose participation was deemed inappropriate by the investigator.

Study endpoints

The co-primary endpoints were the incidences of ischemic stroke and ICH, both symptomatic, within 2 years. Secondary endpoints included each subtype of ICH (intracerebral, subarachnoid, and subdural/epidural hemorrhage). Ischemic stroke, ICH, and each ICH subtype were also assessed in fatal cases who died during the acute hospitalization, patients who were not directly discharged home, and those who needed surgical therapies (hemicraniectomy, hematoma evacuation, or extraventricular drainage only for hemorrhagic patients) as secondary endpoints.

Statistical analysis

The event occurrence for primary and secondary endpoints was described as rate per 100 person-years with 95% confidence interval (CI). The probability of event occurrence during the follow-up period by OAC medication was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis, and p-values were calculated using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated for each clinical outcome by OAC status (DOAC, no-OAC vs warfarin as a reference) using the Cox proportional hazards model. For the multivariable model, sex, age, and major prognostic variables, identical to those used in our article on the initial outcome analysis from ANAFIE, 12 were used as adjusted variables (see the footnote of Supplemental Table 2 for full description of the variables). Statistical methods that account for competing risks were not performed. As a sensitivity analysis for comparison of events between DOAC users and warfarin users, 1:1 propensity score matching technique without replacement was performed using the nearest-neighbor matching method with calipers of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score estimated by logistic regression model. Risk factor analysis to identify factors associated with each endpoint was conducted using the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. A p-value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance; tests were two-sided. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Tokyo, Japan) was used to conduct this analysis.

Results

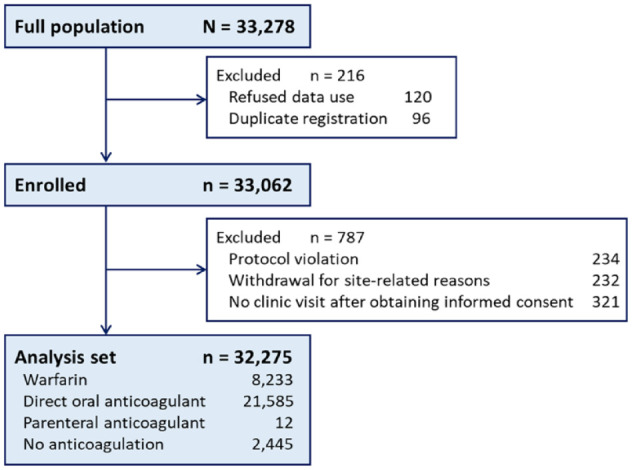

Of the 33,062 patients enrolled, 787 were excluded because of protocol violation, withdrawal for site-related reasons, or loss to follow-up; the remaining 32,275 patients (13,793 women (42.7%); median age, 81.0 years) were analyzed (Figure 1). Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Warfarin was taken for 8233 patients (25.5%) and DOACs for 21,585 (66.9%). Of the remaining 2445 patients (no-OAC), 840 (34.4%) took antiplatelet agents. During the median 1.88-year follow-up, 743 patients (1.24/100 person-years, 95% CI 1.15–1.33) developed ischemic stroke and 453 (0.75/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.68–0.82) developed ICH. Of the latter 453 patients, 189 (0.31/100 person-years, 0.27–0.36) developed intracerebral hemorrhage; 72 (0.12/100 person-years, 0.09–0.15) subarachnoid hemorrhage; and 190 (0.32/100 person-years, 0.27–0.36) subdural/epidural hemorrhage. The subtypes of the remaining 2 patients were not documented.

Figure 1.

Patient study flow.

Ischemic stroke as an endpoint

Baseline characteristics of the 743 patients developing ischemic stroke are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Patients who developed ischemic stroke were older; had higher diastolic blood pressure, lower creatinine clearance, and higher scores of CHADS2, CHA2DS2-VASc, and HAS-BLED; more commonly had persistent/permanent AF as AF types, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, dementia, and histories of cerebrovascular disease, thromboembolic disease, major bleeding, and fall; less commonly received catheter ablation for AF; more commonly took warfarin; and less commonly took DOACs than patients who did not develop ischemic stroke.

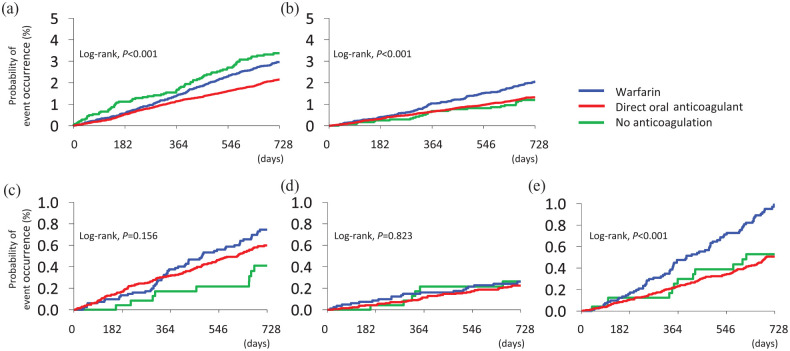

The incidence of ischemic stroke was significantly different among the three groups (warfarin, DOACs, and no-OAC groups; log-rank p < 0.001, Kaplan–Meier analysis, Figure 2(a); note that 12 patients receiving parenteral anticoagulants were excluded from the analysis). Compared with warfarin use, DOAC use was inversely associated (adjusted HR (aHR) 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.97) and no-OAC use was positively associated (aHR 1.62, 95% CI 1.24–2.13) with ischemic stroke (Table 1). On propensity score matching, DOAC use was inversely associated with ischemic stroke relative to warfarin use (aHR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.97).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for endpoints in the total population and by anticoagulant medication (warfarin, DOACs, and no-OAC groups). (a) Ischemic stroke. (b) ICH. (c) Intracerebral hemorrhage. (d) Subarachnoid hemorrhage. (e) Subdural/epidural hemorrhage.

Table 1.

Endpoints by anticoagulant medication.

| Warfarin (n = 8233) |

DOAC (n = 21,585) |

No-OAC (n = 2445) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Incidence | aHR (95% Cl) |

Incidence | aHR (95% Cl) |

|

| Ischemic stroke | |||||

| Overall | 1.50 | 1.09 | 0.82 (0.70–0.97) * | 1.74 | 1.62 (1.24–2.13) * |

| Fatal | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.67 (0.43–1.02) | 0.22 | 1.60 (0.77–3.33) |

| Without home discharge | 1.08 | 0.66 | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) * | 1.17 | 1.54 (1.11–2.14) * |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | |||||

| Overall | 1.03 | 0.67 | 0.68 (0.55–0.83) * | 0.61 | 0.62 (0.40–0.94) * |

| Fatal | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.46 (0.28–0.75) * | 0.16 | 0.72 (0.31–1.69) |

| Without home discharge | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.66 (0.52–0.84) * | 0.52 | 0.74 (0.46–1.17) |

| Requiring surgery | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.64 (0.42–0.99) * | 0.22 | 1.03 (0.49–2.16) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |||||

| Overall | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.85 (0.62–1.18) | 0.20 | 0.55 (0.27–1.13) |

| Fatal | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.56 (0.29–1.10) | 0.09 | 0.93 (0.30–2.92) |

| Requiring surgery | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.77 (0.26–2.30) | 0.07 | 1.62 (0.36–7.43) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||||

| Overall | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.94 (0.55–1.62) | 0.13 | 1.20 (0.46–3.11) |

| Fatal | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.30 (0.11–0.82) * | 0.04 | 0.81 (0.16–4.09) |

| Requiring surgery | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.80 (0.21–15.47) | 0.02 | 2.38 (0.13–44.05) |

| Subdural/epidural hemorrhage | |||||

| Overall | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.53 (0.39–0.72) * | 0.27 | 0.59 (0.31–1.10) |

| Fatal | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.45 (0.15–1.31) | 0.02 | 0.45 (0.05–3.93) |

| Requiring surgery | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.55 (0.33–0.90) * | 0.16 | 0.93 (0.39–2.22) |

DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; HR: hazard ratio, OAC: oral anticoagulant.

Incidences are described as “per 100 person-years.” Adjusted by sex, age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, creatinine clearance, type of AF, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, severe hepatic disease, heart failure, gastrointestinal disease, active cancer, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, thromboembolic disease, major bleeding, fall, catheter ablation, antiplatelet agents, antiarrhythmic drugs, proton pump inhibitors, P-glycoprotein inhibitors, and polypharmacy (⩾ 5 medications).

p < 0.05.

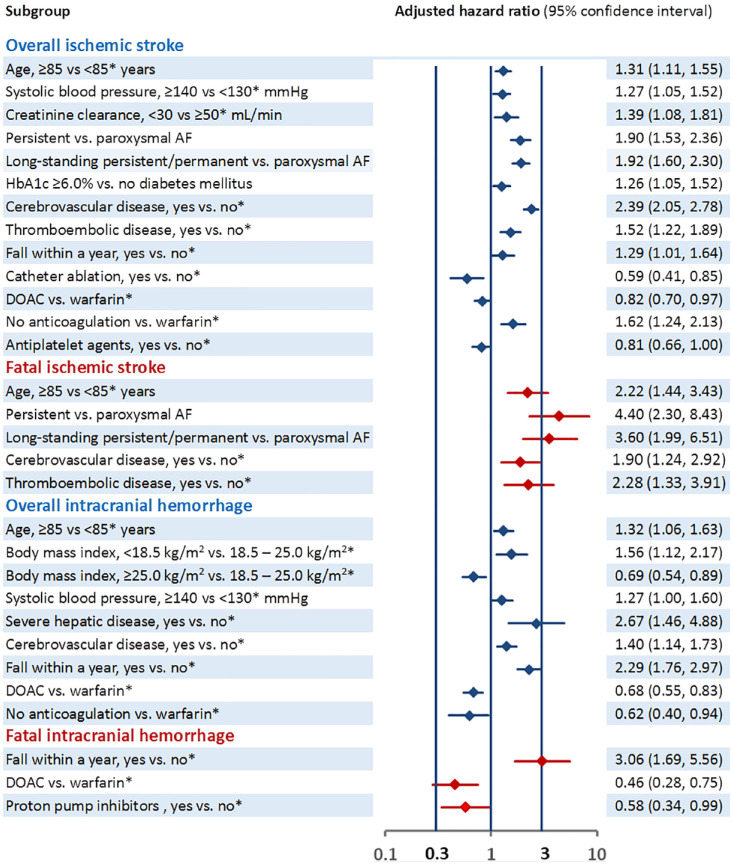

Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 3 show the association of baseline characteristics with ischemic stroke. Older age, higher systolic blood pressure, lower creatinine clearance, persistent/permanent AF, diabetes mellitus with higher glycated hemoglobin A1c level, prior cerebrovascular disease, thromboembolic disease, fall, and no anticoagulation (vs warfarin) were positively associated with ischemic stroke, and prior catheter ablation, DOAC (vs warfarin), and antiplatelet use were inversely associated with ischemic stroke.

Figure 3.

Association between baseline characteristics with co-primary endpoints.

Only variables showing significant associations are listed. Information for all the variables is described in Supplemental Table 1.

*References.

Of the 743 patients who developed ischemic stroke, 100 (0.17/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.13–0.20) were fatal cases. Causes of death were nervous system disorders for 89 patients (all died from the index stroke or stroke recurrence); cardiac disorders, 4 (3 heart failure and 1 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy); infections, 4 (3 pneumonia and 1 sepsis); and others, 3. Supplementalry Table 2 and Figure 3 show the association of baseline characteristics with fatal ischemic stroke; older age, persistent and permanent AF, prior cerebrovascular disease, and thromboembolic disease were positively associated.

Of the 743 patients with ischemic stroke, 483 (0.80/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.73–0.88) were not directly discharged home. DOAC use was inversely associated and no-OAC use was positively associated with ischemic stroke without home discharge (Table 1).

Similar results were seen when 3883 patients taking off-label doses of DOACs were excluded (Supplemental Table 3).

ICH as an endpoint

Baseline characteristics of the 453 patients with ICH are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Patients who developed ICH were older; had lower body mass index, lower creatinine clearance, and higher scores of CHADS2, CHA2DS2-VASc, and HAS-BLED; more commonly had severe hepatic disease, dementia, and histories of cerebrovascular diseases, major bleeding, and fall; less commonly received catheter ablation; more commonly received pacemaker implantation for AF; more commonly took warfarin; and less commonly took DOACs than patients who did not develop ICH.

The incidence of ICH was significantly different among the three groups by anticoagulant medication (log-rank p < 0.001, Figure 2(b)). Compared with warfarin use, both DOAC use (aHR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55–0.83) and no-OAC use (aHR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40–0.94) were inversely associated with ICH (Table 1). On propensity score matching, DOAC use was inversely associated with ICH relative to warfarin use (aHR 0.69, 95% CI 0.54–0.88).

Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 3 show the association of baseline characteristics with ICH. Older age, lower body mass index, higher systolic blood pressure, severe hepatic disease, prior cerebrovascular disease, and fall were positively associated with ICH, and DOAC (vs warfarin) was inversely associated with ICH.

Of the 453 patients who developed ICH, 76 (0.13/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.10–0.15) had fatal cases. Causes of death were nervous system disorders for 68 patients (all died from ICH); infection, 2 (1 pneumonia and 1 sepsis); renal and urinary disorders, 2; and others, 4. Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 3 show the association of baseline characteristics with fatal ICH. Fall was positively associated with fatal ICH, and proton pump inhibitor use and DOAC use (vs warfarin) were inversely associated with fatal ICH.

Of the 453 patients with ICH, 311 (0.52/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.46–0.57) were not directly discharged home, and 103 (0.17/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.14–0.20) required surgery. DOAC use was inversely associated with both of these subgroups (Table 1).

The results were similar when analyzed excluding patients taking off-label doses of DOACs (Supplemental Table 3).

Subtypes of ICH as endpoints

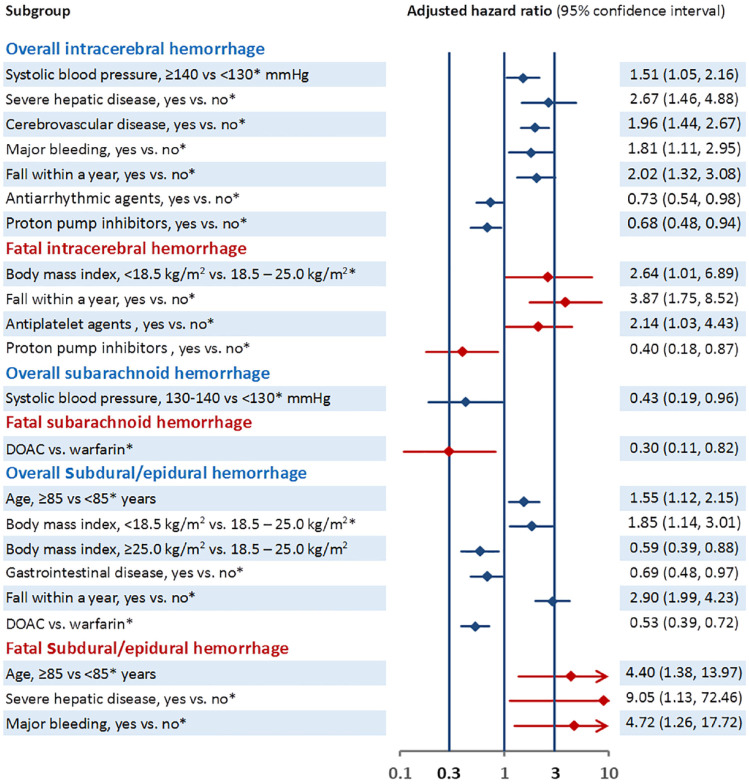

Of the three subtypes of ICH, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a significant difference only in the incidence of subdural/epidural hemorrhage among the three groups when analyzing by anticoagulant medication (log-rank p < 0.001, Figure 2(c) to (e)). Compared with warfarin use, DOAC use was inversely associated with overall subdural/epidural hemorrhage, subdural/epidural hemorrhage requiring surgery, and fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage (Table 1). The results were similar when patients taking off-label doses of DOACs were excluded (Supplemental Table 3).

Supplemental Table 4 and Figure 4 show the association of baseline characteristics with each subtype of ICH. Older age, lower body mass index, and fall were positively associated with overall subdural/epidural hemorrhage, whereas gastrointestinal disease and DOAC use (vs warfarin) were inversely associated. Older age, severe hepatic disease, and prior major bleeding were positively associated with overall fatal subdural/epidural hemorrhage.

Figure 4.

Association between baseline characteristics and each subtype of intracerebral hemorrhage.

Only variables showing significant associations are listed. Information for all the variables is described in Supplemental Table 2 (except for data of fatal cases).

* References.

Discussion

Using the ANAFIE registry, the largest hospital/clinic-based registry on NVAF for elderly population, we determined the incidence of ICH and its subtypes, as well as ischemic stroke, by the strategy of anticoagulation and clarified the baseline characteristics associated with each endpoint in the present substudy. The first major finding of this subanalysis of the ANAFIE Registry was that the incidences of ischemic stroke, ICH, and subdural/epidural hemorrhage as a subtype of ICH were lower in DOAC users versus warfarin users. In addition, the incidences of ischemic stroke without home discharge, fatal ICH, ICH without home discharge, ICH requiring surgery, fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subdural/epidural hemorrhage requiring surgery, all of which indicated severe disability, were also lower with DOAC use. Second, several baseline characteristics other than anticoagulation strategies were associated with the incidence of endpoints. Of these, a history of cerebrovascular disease and persistent/permanent AF showed a relatively strong association with ischemic stroke, and severe hepatic disease and history of fall within 1 year showed relatively strong association with ICH, all having an HR of approximately 2 or more. Fall was also strongly associated with the incidence of subdural/epidural hemorrhage.

Both the incidence of ischemic stroke and that of ICH increase as age increases. In the Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD-Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF), the largest AF registry to date, involving > 50,000 newly diagnosed patients with AF, both the 2-year incidences of non-hemorrhagic stroke and major bleeding (including hemorrhagic stroke) were higher as age increased (1.4% and 1.2%, respectively, in 32,909 patients aged < 75 years versus 2.6% and 2.8%, respectively, in 19,393 patients aged ⩾ 75 years). 16 The incidence rate of stroke/systemic embolism in the ANAFIE Registry (1.62/100 person-years) was similar to the results of other studies/substudies of elderly patients with NVAF (approximately 2–2.5%/year).17–19 In contrast, the incidence rate of major bleeding in the ANAFIE Registry (1.08/100 person-years) was extremely low compared with previous reports of elderly patients with NVAF, which were mostly over 4%/year.17–19 The latter finding was somewhat unexpected, as the Japanese population is known to have a high incidence of ICH, a representative major bleeding event, as compared with Caucasians,20,21 and the percentage of OAC use in the ANAFIE Registry was very high (25.5% were taking warfarin and 66.9%were taking DOACs). This is one of the reasons we performed a detailed analysis of intracranial bleeding and ischemic stroke events, according to anticoagulant use for each event.

In the present subanalysis, DOAC use was significantly associated with an 18% lower risk of ischemic stroke than warfarin. Interestingly, DOACs also significantly decreased the risk of ischemic stroke without home discharge by 28% compared with warfarin and decreased the risk of fatal ischemic stroke by 33% compared with warfarin (without reaching statistical significance), suggesting that DOACs are effective for the prevention of severe ischemic stroke. A history of cerebrovascular disease and persistent/permanent NVAF at baseline were associated with an increased incidence of all ischemic stroke events and fatal ischemic stroke. In another subanalysis of the ANAFIE Registry focusing on stroke survivors, DOACs decreased the risk of ischemic stroke by 11% compared with warfarin (without reaching statistical significance). 22

In the present subanalysis, the incidence of ICH in the DOAC group (0.67/100 person-years) was 32% lower than that in the warfarin group (1.03/100 person-years) and similar to that in the no-OAC group (0.61/100 person-years). The incidences of fatal ICH, ICH without home discharge, and ICH requiring surgery, all of which suggest severe hemorrhage, were 36–54% lower with DOAC use than with warfarin use. DOACs reportedly halved the risk of ICH relative to warfarin in other studies of patients ⩾ 75 years with NVAF.13,14 DOAC-associated ICH were generally associated with milder initial severity and better functional outcome than warfarin-associated ICH.23–26

Severe hepatic disease and history of fall within 1 year were prominently associated with the incidence of any or fatal ICH. Head injury is an established risk factor for ICH, and even mild trauma, such as ground-level fall, may cause intracerebral hemorrhage in elderly patients especially during anticoagulation treatment. 27 Of 77,834 patients with head injury in a retrospective cohort study, including 9214 patients taking DOACs and 3703 patients taking warfarin, patients taking DOACs were reported to have a 30% lower risk of ICH than those taking warfarin. 28

Subdural/epidural hemorrhage was the most common subtype (0.32/100 person-years) among the three subtypes of ICH in the ANAFIE Registry. As this type of hemorrhage mainly results from a tear in the veins bridging the meninges due to head injury even if the injury is trivial and subclinical, it often occurs in elderly populations with a high risk of fall. 29 In addition, the preventive effect of DOACs relative to warfarin was the most prominent for subdural/epidural hemorrhage (aHR 0.53) in the present subanalysis. Both the risks of fatal subdural/epidural hemorrhage and subdural/epidural hemorrhage requiring surgery were also halved by DOACs. DOACs seem to be effective for elderly patients with frailty or dementia who tend to fall frequently.

The main strength of our study was that, to the best of our knowledge, it is the most extensive registration study for elderly patients with NVAF, and there were very low withdrawal rates during the 2-year follow-up period (2.3%). This study had several limitations as described initial outcome analysis from ANAFIE. 12 For example, as the percentage of elderly NVAF patients taking OACs was relatively high compared with that reported in previous observational studies from Japan, 30 the results might not be generalizable to other populations with lower OAC use. Second, the present subanalysis did not take into account OAC changes during follow-up. Third, both patients newly diagnosed with NVAF and those with established NVAF or those who were receiving anticoagulants prior to enrollment were allowed to participate, and this might have affected the incidence of events. In addition, although antidotes unique to each OAC might decrease the incidence of fatal events and events requiring surgery, andexanet alfa, a specific antidote to factor Xa inhibitors, 31 was not approved for clinical use during the study period of the ANAFIE Registry. Finally, the present subgroup analyses might be exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

In conclusion, patients aged ⩾ 75 years with NVAF taking DOACs had lower risks of ischemic stroke, ICH, and subdural/epidural hemorrhage than those taking warfarin. These patients also had lower risks of disabling ischemic stroke and disabling ICH based on fatality rates, of being directly discharged home, or needing surgical intervention. Fall was strongly associated with the risks of intracranial and subdural/epidural hemorrhage.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-wso-10.1177_17474930231175807 for Risk of both intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic stroke in elderly individuals with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation taking direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin: Analysis of the ANAFIE registry by Masayuki Shiozawa, Masatoshi Koga, Hiroshi Inoue, Takeshi Yamashita, Masahiro Yasaka, Shinya Suzuki, Masaharu Akao, Hirotsugu Atarashi, Takanori Ikeda, Ken Okumura, Yukihiro Koretsune, Wataru Shimizu, Hiroyuki Tsutsui, Atsushi Hirayama, Jin Nakahara, Satoshi Teramukai, Tetsuya Kimura, Yoshiyuki Morishima, Atsushi Takita, Takenori Yamaguchi and Kazunori Toyoda in International Journal of Stroke

Acknowledgments

The authors thank IQVIA Services Japan and EP-CRSU for their partial support in the conduct of this Registry; Keyra Martinez Dunn, MD, of Edanz for medical writing support; and Daisuke Chiba, of Daiichi Sankyo, for providing support in the article preparation.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All the following conflicts are outside the submitted work. M.S. reports no conflicts. M.K. reports honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo (DS), Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Otsuka, and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim (NBI); research funds from Takeda, DS, NBI, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, and Shionogi; and serves on the scientific advisory board for Ono. H.I. reports remuneration from DS and NBI, and consultancy fees from DS. T.Y. reports research funding from BMS, Bayer, and DS; article fees from DS and BMS; and remuneration from DS, BMS, Bayer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Toa Eiyo. M.Y. reports remuneration from NBI and DS. S.S. reports research funding from DS, and remuneration from BMS and DS. M.A. reports research funding from Bayer and DS, and remuneration from BMS, NBI, Bayer, and DS. H.A. reports remuneration from DS. T.I. reports research funding from DS and Bayer, and remuneration from DS, Bayer, NBI, and BMS. K.O. reports remuneration from NBI, DS, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic. Y.K. reports remuneration from DS, BMS, and NBI. W.S. reports research funding from BMS, DS, and NBI, and remuneration from DS, Pfizer, BMS, Bayer, and NBI. H.T. reports research funding from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, NBI, IQVIA Services Japan, MEDINET, Medical Innovation Kyushu, Kowa Pharmaceutical, DS, Johnson & Johnson, and NEC; consulting fees from Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bayer, and NBI; remuneration from Kowa Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma, NBI, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, DS, Novartis, Bayer, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, and Nippon Rinsho; and has served in a leadership or fiduciary role in Japanese Heart Failure Society. A.H. participated in a course endowed by Boston Scientific Japan, reports research funding from DS and Bayer, and remuneration from Bayer, DS, BMS, and NBI. J.N. reports lecture honoraria from DS, NBI, and Eisai, and research support from Pfizer. S.T. reports research funding from NBI, and remuneration from DS, Sanofi, Takeda, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Solasia Pharma, Bayer, Sysmex, Nipro, NapaJen Pharma, Gunze, and Atworking. T.K., Y.M., and A.T. are employees of DS. T.Y. acted as an Advisory Board member of DS and reports remuneration from DS and BMS. K.T. reports lecture honoraria from DS, Otsuka, Novartis, Bayer, and BMS.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.

ORCID iDs: Masatoshi Koga  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6758-4026

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6758-4026

Kazunori Toyoda  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8346-9845

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8346-9845

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lip GYH, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2018; 154: 1121–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the society of thoracic surgeons. Circulation 2019; 140: e125–e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the EACTS: the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the ESC developed with the special contribution of the EHRA of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miyamoto S, Ogasawara K, Kuroda S, et al. Japan Stroke Society Guideline 2021 for the treatment of stroke. Int J Stroke 2022; 17: 1039–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cowan JC, Wu J, Hall M, Orlowski A, West RM, Gale CP. A 10 year study of hospitalized atrial fibrillation-related stroke in England and its association with uptake of oral anticoagulation. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 2975–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forslund T, Komen JJ, Andersen M, et al. Improved stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation after the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: the Stockholm experience. Stroke 2018; 49: 2122–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maggioni AP, Dondi L, Andreotti F, et al. Four-year trends in oral anticoagulant use and declining rates of ischemic stroke among 194,030 atrial fibrillation patients drawn from a sample of 12 million people. Am Heart J 2020; 220: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Carlo A, Bellino L, Consoli D, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the Italian elderly population and projections from 2020 to 2060 for Italy and the European Union: the FAI Project. Europace 2019; 21: 1468–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inoue H, Yamashita T, Akao M, et al. Prospective observational study in elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: rationale and design of the All Nippon AF In the Elderly (ANAFIE) registry. J Cardiol 2018; 72: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koretsune Y, Yamashita T, Akao M, et al. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics in the All Nippon AF In the Elderly (ANAFIE) registry. Circ J 2019; 83: 1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamashita T, Suzuki S, Inoue H, et al. Two-year outcomes of more than 30 000 elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the All Nippon AF In the Elderly (ANAFIE) registry. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2022; 8: 202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell A, Watson MC, Welsh T, McGrogan A. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists for people aged 75 years and over with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schäfer A, Flierl U, Berliner D, Bauersachs J. Anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in elderly patients. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2020; 34: 555–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carnicelli AP, Hong H, Connolly SJ, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: patient-level network meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials with interaction testing by age and sex. Circulation 2022; 145: 242–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fox KAA, Virdone S, Pieper KS, et al. GARFIELD-AF risk score for mortality, stroke, and bleeding within 2 years in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2022; 8: 214–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Wojdyla DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin among elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the Rivaroxaban Once Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF). Circulation 2014; 130: 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halvorsen S, Atar D, Yang H, et al. Efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with warfarin according to age for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: observations from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1864–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kato ET, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krishnamurthi RV, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global and regional burden of first-ever ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Glob Health 2013; 1: e259–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshimoto T, Toyoda K, Ihara M, et al. Impact of previous stroke on clinical outcome in elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: ANAFIE registry. Stroke 2022; 53: 2549–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adachi T, Hoshino H, Takagi M, Fujioka S. Volume and characteristics of intracerebral hemorrhage with direct oral anticoagulants in comparison with warfarin. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 2017; 7: 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurogi R, Nishimura K, Nakai M, et al. Comparing intracerebral hemorrhages associated with direct oral anticoagulants or warfarin. Neurology 2018; 90: e1143–e1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suda S, Aoki J, Shimoyama T, et al. Characteristics of acute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in patients receiving oral anticoagulants. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2019; 28: 1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller MM, Lowe J, Khan M, et al. Clinical and radiological characteristics of vitamin K versus non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulation-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2019; 31: 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaetani P, Revay M, Sciacca S, Pessina F, Aimar E, Levi D, Morenghi E. Traumatic brain injury in the elderly: considerations in a series of 103 patients older than 70. J Neurosurg Sci 2012; 56: 231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grewal K, Atzema CL, Austin PC, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage after head injury among older patients on anticoagulation seen in the emergency department: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ 2021; 193: E1561–E1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hart RG, Diener HC, Yang S, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in atrial fibrillation patients during anticoagulation with warfarin or dabigatran: the RE-LY trial. Stroke 2012; 43: 1511–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akao M, Ogawa H, Masunaga N, et al. 10-Year trends of antithrombotic therapy status and outcomes in Japanese atrial fibrillation patients—the Fushimi AF Registry. Circ J 2022; 86: 726–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Connolly SJ, Crowther M, Eikelboom JW, et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-wso-10.1177_17474930231175807 for Risk of both intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic stroke in elderly individuals with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation taking direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin: Analysis of the ANAFIE registry by Masayuki Shiozawa, Masatoshi Koga, Hiroshi Inoue, Takeshi Yamashita, Masahiro Yasaka, Shinya Suzuki, Masaharu Akao, Hirotsugu Atarashi, Takanori Ikeda, Ken Okumura, Yukihiro Koretsune, Wataru Shimizu, Hiroyuki Tsutsui, Atsushi Hirayama, Jin Nakahara, Satoshi Teramukai, Tetsuya Kimura, Yoshiyuki Morishima, Atsushi Takita, Takenori Yamaguchi and Kazunori Toyoda in International Journal of Stroke