Abstract

Background

According to the guidelines of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) conducted by bystanders, two methods of CPR are feasible: standard CPR (sCPR) with mouth-to-mouth ventilations and continuous chest compression-only CPR (CCC) without rescue breathing. The goal herein, was to evaluate the effect of sCPR (30:2) and CCC on resuscitation outcomes in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients.

Methods

This study was a systematic review and meta-analysis. Using standardized criteria, Pub- Med, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE and Cochrane Collaboration were searched for trials assessing the effect of sCPR vs. CCC on resuscitation outcomes after adult OHCA. Random-effects model meta-analysis was applied to calculate the mean deviation (MD), odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Overall, 3 randomized controlled trials and 12 non-randomized trials met the inclusion criteria. Survival to hospital discharge with sCPR was 10.2% compared to 9.3% in the CCC group (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 0.93–1.16; p = 0.46). Survival to hospital discharge with good neurological outcome measured with the cerebral performance category (CPC 1 or 2) was 6.5% for sCPR vs. 5.8% for CCC (OR = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.84–1.20; p = 0.98). Prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in sCPR and CCC groups was 15.9% and 14.8%, respectively (OR = 1.13; 95% CI: 0.91–1.39; p = 0.26). Survival to hospital admission with ROSC occurred in 29.5% of the sCPR group compared to 28.4% in CCC group (OR = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.89–1.63; p = 0.24).

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that there were no significant differences in the resuscitation outcomes between the use of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation and chest compression only.

Keywords: out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, chest compression, continuous compressions

Introduction

Despite significant advances in the delivery of care, the survival rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is poor [1]. According to study by Nadolny et al. [2] return of spontaneous circulation refers to 35.1% OHCA patients and only 28.7% patients are admitted to the hospital. Current recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHA) [3], as well as the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) [4], place great emphasis on high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). This includes high-quality chest compressions [5] and minimizing interruptions during chest compressions [6].

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation can be a heavy burden for bystanders. In the past, bystanders often did not undertake CPR due to the resistance associated with the need to perform mouth-to-mouth ventilation [7, 8]. For this reason, the ERC and AHA guidelines have introduced two possible CPR techniques for bystanders. The first is the standard method of performing cycles based on 30 compressions with a pause for two ventilations (30:2). The second is based on continuous chest compression without the need for pauses for rescue breaths — which is intended to encourage people to undertake more frequent resuscitation efforts [9].

The systematic review and meta-analysis are aimed to evaluate the effect of standard CPR (sCPR) (30:2) and continuous chest compressions without rescue breaths (CCC) on resuscitation outcomes in patients with OHCA.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [10] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11].

Search strategy

Screening of papers and the data extraction were undertaken by two independent authors (K.B. and M.P.), using predefined selection criteria and a data extraction sheet. Disagreements were resolved by a third investigator (L.S.). PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE and Cochrane Collaboration database, English language articles published from the databases inception to 21st July 2021 were searched. The search was performed using the following terms: “cardiopulmonary arrest” OR “heart arrest” OR “cardiac arrest” OR “heart attack” OR “sudden cardiac death” OR “out-oh-hospital cardiac arrest” OR “OHCA” OR “asystole” OR “PEA” OR “pulseless electrical activity” OR “VF” OR “ventricular fibrillation” OR “VT” OR “ventricular tachycardia” AND “resuscitation” OR “CPR” OR “chest compression” OR “30:2” OR “conventional resuscitation” OR “continuous compression”. Additionally, we reviewed the bibliographies of the identified trials and evaluated review articles for relevant references.

Study selection

Included studies were required to document the following parameters: (1) Participants; OHCA in adult patients, (2) Intervention; conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation, (3) Comparison; chest compression without ventilation (CC-CPR), (4) Outcomes; detailed information for mortality, (5) Study design; randomized controlled trials and observational studies.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: (A) studies including pediatric patient; (B) were classed as Letter to Editor, Correspondence, or as an Editorial; (C) animal or simulation trials; (D) conference abstract; (E) guidelines. Studies were also excluded if the full paper was not available in English.

Outcomes

Primary end points were in-hospital or 30-day mortality and survival to hospital discharge with good neurological outcome defined as the cerebral performance category (CPC) score 1 or 2 [12]. Secondary end points were return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival to hospital admission.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (K.B. and J.C.) independently extracted and entered the following data into a predefined extraction table: study characteristics, mortality, and neurologic outcome. If multiple publications of the same dataset were obvious or confirmed by the authors, the one with the most extractable and complete information was chosen. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (L.S.).

The risk of bias (RoB) of the included studies was independently assessed by 3 reviewers (K.B., A.G. and J.S.) according to the revised tool for risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB 2 tool) [13] and Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies — of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [14]. All disagreements were resolved by referral to a third author (L.S.) if necessary. ROBINS examines seven domains of bias: (1) confounding; (2) selection of participants; (3) classification of interventions; (4) deviations from intended interventions; (5) missing data; (6) measurement of outcomes; and (7) selection of the reported result. The overall ROBINS-I judgment at domain and study level was attributed according to the criteria specified in the ROBVIS tool [15].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using the STATA software (Version 13.0 StataCorp) and the Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration 2014). Random-effects meta-analyses of continuous data with mean deviations (MDs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) [16] were performed. For dichotomous data, odds ratios (ORs) as the effect measure with 95% CI were used. When the continuous outcome was reported in a study as median, range, and interquartile range, means and standard deviations were estimated using the formula described by Hozo et al. [17]. For meta-analysis the random effects model was used (assuming a distribution of effects across studies) to weigh estimates of studies in proportion to their significance [10].

Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics, with low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity designated as 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively [18]. All variables were analyzed using the DerSimonian–Laird random effects model. Where there were fewer than 10 included studies, publication bias was unable to be formally assessed [10]. A p-value of less than 0.05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

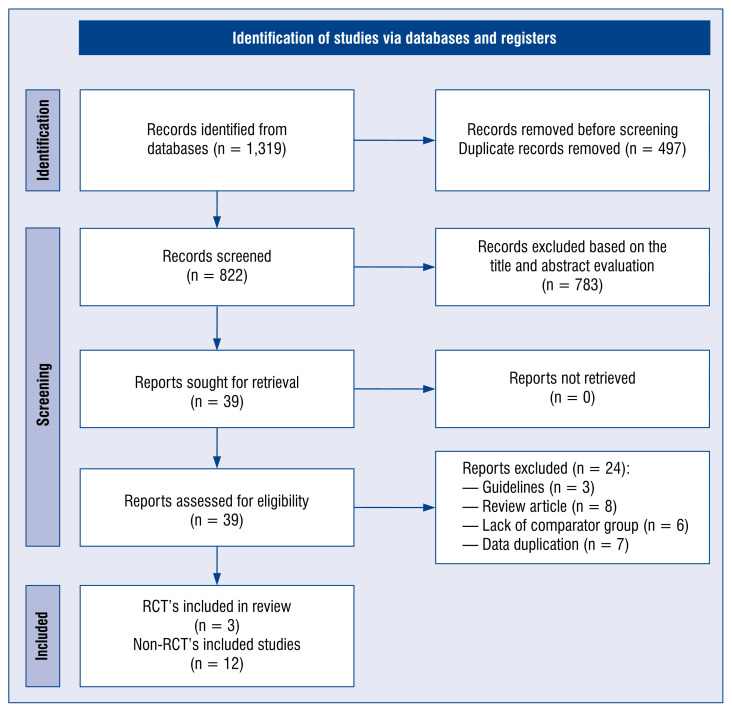

A PRISMA flowchart, including the reasons for excluding studies, is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1319 records were identified, of which duplicate records and further 783 records were excluded based on the title and abstract evaluation. After review of the remaining 39 articles in full, 15 articles [19–33] ultimately met the inclusive criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing stages of database searches and study selection as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline; RCT — randomized controlled trials.

Table 1 details the characteristics of the selected trials. Included trials were published between 2000 and 2021, totaling 220,945 OHCA patients (80,051 in standard CPR group and 140,894 in the CCC group). Overall, 3 studies were randomized controlled trials [19–21] with the remaining being non-randomized [22–33].

Table 1.

The information of 18 studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Country | Study design | Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation (30:2) | Continuous chest compression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| No. | Age | Sex, male | No. | Age | Sex, male | |||

| Hallstrom et al. 2000 | USA | Randomized controlled trials | 279 | 68.5 | 181 (64.9%) | 241 | 67.9 | 145 (60.2%) |

| Rea et al. 2010 | Multi-country | Randomized controlled trials | 960 | 63.9 ± 16.3 | 613 (63.9%) | 981 | 63.4 ± 16.5 | 659 (67.2%) |

| Svensson et al. 2010 | Sweden | Randomized controlled trials | 656 | NS | 444 (67.7%) | 620 | NS | 412 (66.5%) |

| Bobrow et al. 2010 | USA | Prospective observational cohort study | 666 | 63.8 ± 15.2 | 458 (68.8%) | 849 | 63.1 ± 15.1 | 578 (68.1%) |

| Bohm et al. 2007 | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study | 8,209 | 63 ± 18 | 6,157 (75.0%) | 1,145 | 66 ± 16 | 882 (77.0%) |

| Iwami et al. 2007 | Japan | Prospective, population-based, observational study | 783 | 69.1 ± 16.1 | 483 (61.8%) | 544 | 68.2 ± 15.3 | 359 (66.2%) |

| Javaudin et al. 2020 | French | Multicenter retrospective study | 1,544 | 64.1 ± 16.7 | 1,057 (68.5%) | 6,997 | 64.1 ± 16.7 | 1,057 (68.5%) |

| Kitamura et al. 2018 | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | 41,013 | 74.1 ± 18.2 | 22,155 (54.0%) | 102,487 | 75.3 ± 15.9 | 60,901 (59.4%) |

| Olasveengen 2008 | Norway | Retrospective, observational study | 281 | 63 ± 18 | 209 (74.4%) | 145 | 62 ± 18 | 97 66.9%) |

| Ong et al. 2008 | Singapore | Prospective, multi-phase, observational study | 287 | 56.0 ± 20.1 | 218 (76.0%) | 154 | 58.6 ± 15.8 | 115 (74.7%) |

| Riva et al. 2019 | Sweden | Multicenter retrospective study | 11,920 | 69.5 ± 3.3 | 8,511 (71.4%) | 6,339 | 71.8 ± 3.2 | 4,412 (69.6%) |

| Schmicker et al. 2021 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 10,942 | 65.5 ± 4 | 6,904 (63.1%) | 15,868 | 66 ± 4 | 10,075 (63.5%) |

| SOS-KANTO 2017 | Japan | Prospective, multi-center, observational study | 712 | 68.3 ± 7.2 | 462 (64.9%) | 439 | 67.8 ± 7.2 | 316 (72.0%) |

| Waalewijn et al. 2001 | Netherlands | Prospective study | 437 | NS | NS | 41 | NS | NS |

| Wnent et al. 2021 | Multi-center | Prospective, multi-center study | 1,362 | 65.1 ± 19.0 | 912 (67.1%) | 4,044 | 66.7 ± 16.6 | 2,777 (68.7%) |

NS — not specified

Risk of bias in included studies

RoB 2 and ROBINS-I tools were used to evaluate methodological quality and risk of bias respectively for the randomized and non-randomized studies. Summary of the risk of bias of included trials is presented in Supplementary data (Suppl. Figs. S1, S2).

Meta-analysis outcomes

A polled analysis of the 13 studies indicated survival to hospital discharge with sCPR was 10.2% compared to the 9.3% in CCC group (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 0.93–1.16; p = 0.46; Table 2). Sub-analysis comparing survival to hospital discharge between sCPR and CCC was not significantly different in randomized (6.2% vs. 6.1%, respectively; OR = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.78–1.12; p=0.48) or non-randomized trials (10.9% vs. 9.8%; OR = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.95–1.24; p = 0.24).

Table 2.

Resuscitation outcomes in included trials.

| Parameter | No. of studies | Events/participants | Events | Heterogeneity between trials | P-value for differences across groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation (sCPR) (30:2) | Continuous chest compression (CCC) | OR | 95%CI | P-value | I2 statistic | |||

| SHD | 13 | 8,005/78,659 (10.2%) | 13,066/139,786 (9.3%) | 1.04 | 0.93–1.16 | < 0.001 | 76% | 0.46 |

| RCT | 3 | 753/12,176 (6.2%) | 1,036/17,086 (6.1%) | 0.94 | 0.78–1.12 | 0.20 | 37% | 0.48 |

| Non-RCT | 10 | 7,252/66,483 (10.9%) | 12,030/122,700 (9.8%) | 1.08 | 0.95–1.24 | < 0.001 | 78% | 0.24 |

| SHD with good neurological outcome | 7 | 2,945/45,286 (6.5%) | 6,476/111,615 (5.8%) | 1.00 | 0.84–1.20 | 0.06 | 51% | 0.98 |

| ROSC | 5 | 6,962/43,726 (15.9%) | 15,940/107,374 (14.8%) | 1.13 | 0.91–1.39 | < 0.001 | 86% | 0.26 |

| Survival to hospital admission with ROSC | 5 | 1,154/3,911 (29.5%) | 3,229/11,381 (28.4%) | 1.20 | 0.89–1.63 | < 0.001 | 85% | 0.24 |

CI — confidence interval; OR — odds ratio; RCT — randomized controlled trial; ROSC — return of spontaneous circulation; SHD — survival to hospital discharge

Survival to hospital discharge with good neurological outcome (CPC 1 or 2) was reported in 7 studies and was 6.5% for sCPR compared to 5.8% for CCC (OR = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.84–1.20; p = 0.98). Five studies reported ROSC. Polled analysis showed that ROSC in sCPR and CCC groups was 15.9% and 14.8%, respectively (OR = 1.13; 95% CI: 0.91–1.39; p = 0.26).

Survival to hospital admission after ROSC was observed in 29.5% of participants in the sCPR group compared to 28.4% in CCC group (OR = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.89–1.63; p = 0.24).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, standard CPR with chest compression only for adult OHCA resuscitation was compared. No significant differences were found between both arms for all outcomes. It was felt that data supporting this important finding is sufficient to recommend changes in standard practice. While the number of individuals enrolled in the totality of randomized controlled trials [19–21] included in the present analysis is relatively limited (n = 3,737), not a single randomized trial demonstrated a significant clinical outcome benefit with the application of rescue breathing. When considered in conjunction with the large number of patients included in the observational trials (n = 213,123), the summation of the data equates to 216,680 patients and is sufficient to support the removal of rescue breathing from standard guidelines of bystander CPR in OHCA.

There are multiple reasons that compression only CPR should be the preferred option for bystander CPR. These include the fact that shared secretions that occur from mouth-to-mouth resuscitation serves as an impediment for adoption in unrelated bystanders, and because it is easier to instruct an unexperienced provider by telephone in the performance of chest compression only CPR when guidance is obtained remotely [34, 35]. Furthermore, in the time of a global pandemic, the performance of rescue breathing must be considered an avoidable high-risk activity for the transmission of pathogens from the patient to the rescue breathing provider [36–39].

It should be noted that the findings of the randomized controlled trials most likely represent the “best case scenario”. This is because the performance of these trials occurred in environments with extremely well-developed Emergency Medical Service (EMS) systems; most likely some of the most sophisticated on the globe. The fact that their outcomes show no benefit with the addition of rescue breathing to standard CPR practice suggests that there would be even less outcome improvement in systems with longer times to advanced cardiac life support and transport to hospital. Further, the majority of patients enrolled in the randomized controlled trials occurred in urban environments, in areas of relative wealth. It would not be expected that the addition of rescue breathing would be improved in a rural or poor environment.

Finally, while the numeric majority of the present data is obtained from observational trials performed in industrialized nations with relatively high performing EMS infrastructure, it was found that the summation of their reported outcomes were similar to the randomized controlled trials. In the largest (n = 143,500) observational trial [26], multivariate analysis and propensity matching reported significant outcome improvements with chest compression only CPR. Considering the next 3 largest observational studies [23, 29, 30], n = = 68,530, found mixed results, with both Riva et al. [29], n = 30,445, and Schmicker et al. [30], n = = 26,810, reporting improvements by the addition of rescue breathing, and Bohm et al. [23], n = 11,275, no difference in outcomes was found.

This meta-analysis should be interpreted with consideration of certain limitations. First, only 3 of the included studies are randomized controlled trials. The others are non-randomized studies that are assumed to carry a higher risk of unmeasured bias than randomized controlled trials. Another limitation is the fact that the included studies limited outcomes to discharge from hospital or 30 days after cardiac arrest. Only one study by Iwami et al. [24] reported an annual survival rate of 5.5% for standard CPR and 5.0% for CC-CPR, respectively.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that there were no significant differences in the resuscitation outcomes between the use of standard CPR and chest compression only. The choice of standard CPR and chest compression without mouth-to-mouth ventilation remains the bystander’s preference, however guideline changes may be considered.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the ERC Research Net and by the Polish Society of Disaster Medicine.

Footnotes

This paper was guest edited by Prof. Togay Evrin

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Borkowska MJ, Smereka J, Safiejko K, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated by emergency medical service teams during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiol J. 2021;28(1):15–22. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadolny K, Bujak K, Kucap M, et al. The Silesian Registry of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Study design and results of a three-month pilot study. Cardiol J. 2020;27(5):566–574. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, et al. Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S366–S468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olasveengen TM, Semeraro F, Ristagno G, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Basic Life Support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smereka J, Madziala M, Szarpak L. Comparison of two infant chest compression techniques during simulated newborn cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed by a single rescuer: a randomized, crossover multicenter trial. Cardiol J. 2019;26(6):761–768. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewy GA, Zuercher M, Hilwig RW, et al. Improved neurological outcome with continuous chest compressions compared with 30, 2 compressions-to-ventilations cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a realistic swine model of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2525–2530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Jeabory M, Safiejko K, Bialka S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Is it as bad as we think? Cardiol J. 2020;27(6):884–885. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorge-Soto C, Abilleira-González M, Otero-Agra M, et al. Schoolteachers as candidates to be basic life support trainers: a simulation trial. Cardiol J. 2019;26(5):536–542. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majer J, Jaguszewski MJ, Frass M, et al. Does the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation feedback devices improve the quality of chest compressions performed by doctors? A prospective, randomized, cross-over simulation study. Cardiol J. 2019;26(5):529–535. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019) 2019 doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2031;134(3):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds EC, Zenasni Z, Harrison DA, et al. How do information sources influence the reported Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) for in-hospital cardiac arrest survivors? An observational study from the UK National Cardiac Arrest Audit (NCAA) Resuscitation. 2019;141:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N, DerSimonian R, et al. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallstrom A, Cobb L, Johnson E, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by chest compression alone or with mouth-to-mouth ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(21):1546–1553. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rea T, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, et al. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):423–433. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0908993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svensson L, Bohm K, Castrèn M, et al. Compression-only CPR or standard CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):434–442. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0908991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panchal AR, Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, et al. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010;304(13):1447–1454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohm K, Rosenqvist M, Herlitz J, et al. Survival is similar after standard treatment and chest compression only in out-of-hospital bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2007;116(25):2908–2912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, et al. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiac-only resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007;116(25):2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javaudin F, Raiffort J, Desce N, et al. GR-RéAC. Neurological outcome of chest compression-only bystander CPR in asphyxial and non-asphyxial out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020:1–25. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1852354. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitamura T, Kiyohara K, Nishiyama C, et al. Chest compression- only versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bystander-witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of medical origin: A propensity score-matched cohort from 143,500 patients. Resuscitation. 2018;126:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olasveengen TM, Wik L, Steen PA. Standard basic life support vs. continuous chest compressions only in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(7):914–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong ME, Ng FS, Anushia P, et al. Comparison of chest compression only and standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Singapore. Resuscitation. 2008;78(2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riva G, Ringh M, Jonsson M, et al. Survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation or chest compressions only before arrival of emergency medical services: nationwide study during three guideline periods. Circulation. 2019 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038179. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmicker RH, Nichol G, Kudenchuk P, et al. CPR compression strategy 30:2 is difficult to adhere to, but has better survival than continuous chest compressions when done correctly. Resuscitation. 2021;165:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SOS-KANTO study group. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders with chest compression only (SOS-KANTO): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):920–926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waalewijn RA, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Bystander initiated actions in out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: results from the Amsterdam Resuscitation Study (ARRESUST) Resuscitation. 2001;50(3):273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wnent J, Tjelmeland I, Lefering R, et al. To ventilate or not to ventilate during bystander CPR — A EuReCa TWO analysis. Resuscitation. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.06.006. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kłosiewicz T, Puślecki M, Zalewski R, et al. Analysis of the quality of chest compressions during resuscitation in an understaffed team — randomised crossover manikin study. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2020;5(1):24–29. doi: 10.5603/demj.a2020.0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zalewski R, Przymuszala P, Klosiewicz T, et al. The effectiveness of ‘practice while watching’ technique for the first aid training of the chemical industry employees. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2019;4(3):83–91. doi: 10.5603/demj.2019.0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szarpak L, Ruetzler K, Dabrowski M, et al. Dilemmas in resuscitation of COVID-19 patients based on current evidence. Cardiol J. 2020;27(3):327–328. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attila K, Ludwin K, Evrin T, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on airway management in prehospital resuscitation. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2020;5(4):216–217. doi: 10.5603/demj.a2020.0047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malysz M, Jaguszewski M, Szarpak L, et al. Comparison of different chest compression positions for use while wearing CBRNPPE: a randomized crossover simulation trial. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2020 doi: 10.5603/demj.a2020.0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolan JP, Monsieurs KG, Bossaert L, et al. European Resuscitation Council COVID-19 guidelines executive summary. Resuscitation. 2020;153:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.