Abstract

A nested PCR was developed to amplify the variable region of the kinetoplast minicircles of all Leishmania species which infect mammals. Each Leishmania parasite contains approximately 10,000 kinetoplast DNA minicircles, which are unequally distributed among approximately 10 minicircle classes. The PCR primers were designed to bind within the 120-bp conserved region which is common to all minicircle classes; the remaining approximately 600 bp of each minicircle is highly conserved within each minicircle class but highly divergent between classes. The nested PCR generated a strong signal from a minimum of 0.1 fg of Leishmania DNA. Restriction digests of the amplicons from the highest dilutions suggested that minicircles from only a limited number of minicircle classes had acted as template in the reaction. One PCR product was directly sequenced and found to be derived from only one minicircle class. Since the primers amplify all minicircle classes, this indicated that as little as 1/10 of one Leishmania parasite was present in the PCR template. This demonstrated that the nested PCR achieved very nearly the maximum theoretically possible sensitivity and is therefore a potentially useful method for diagnosis. The nested PCR was tested for sensitivity on 20 samples from patients from the Timargara refugee camp, Pakistan. Samples were collected by scraping out a small amount of tissue with a scalpel from an incision at the edge of the lesion; the tissue was smeared on one microscope slide and placed in a tube of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, in which the sample was stable for at least 1 month. DNA for PCR was prepared by being bound to silica in the presence of 6 M guanidine thiocyanate; washed in guanidine thiocyanate, ethanol, and acetone; and eluted with 10 mM Tris-HCl. PCR products of the size expected for Leishmania tropica were obtained from 15 of the 20 samples in at least one of three replicate reactions. The negative samples were from lesions that had been treated with glucantime or were over 6 months old, in which parasites are frequently scanty. This test is now in routine use for the detection and identification of Leishmania parasites in our clinical laboratory. Fingerprints produced by restriction digests of the PCR products were defined as complex or simple. There were no reproducible differences between the complex restriction patterns of the kinetoplast DNA of any of the parasites from Timargara camp with HaeIII and HpaII. The simple fingerprints were very variable and were interpreted as being the product of PCR on a limited subset of minicircle classes, and consequently, it was thought that the variation was determined by the particular minicircle classes that had been represented in the template. The homogeneity of the complex fingerprints suggests that the present epidemic of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Timargara camp may be due to the spread of a single clone of L. tropica.

PCR-based methods for detecting Leishmania species in clinical samples have been developed to amplify rRNA and miniexon genes, kinetoplast DNA (kDNA), and repetitive nuclear DNA sequences (7, 13, 16, 17, 19). These methods are of varying specificity: some will detect all Leishmania species while other methods will identify the infecting Leishmania parasite to the species complex level. This information is usually sufficient for diagnostic purposes; however, higher-resolution identification is often required for understanding the epidemiology of leishmaniasis. However, it is necessary to isolate parasites in culture before using any of the existing high-resolution techniques such as isoenzymes, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, and schizodemes. Recovery of parasites in culture is rarely more than about 70% efficient even with easily cultured parasites. Leishmania braziliensis is frequently difficult to isolate, and in Tunisia, Leishmania infantum parasites causing cutaneous lesions have never been successfully cultured in the standard NNN blood agar medium used for the isolation of Leishmania (5). Furthermore, it is possible that mixed infections will be missed due to the different growth rates of different strains in blood agar culture (10).

The kinetoplast, an organelle unique to the kinetoplastids, contains approximately 10,000 small circular DNAs known as kDNA minicircles which are between 600 and 800 bp in size in members of the genus Leishmania. The abundance of these molecules has made them the target for a number of diagnostic tests (2, 4, 5). Kinetoplast minicircles code for guide RNAs that are involved in editing the mitochondrial genes of trypanosomatids. The 10,000 kinetoplast minicircles are distributed among about 10 different sequence classes. Within each minicircle class, sequences may vary by 1 or 2%. The number of minicircles in each class is very variable (4). The minicircle is divided into an approximately 120-bp conserved region and an approximately 600-bp variable region. The conserved region contains shorter blocks that are conserved throughout the genus Leishmania and in some other trypanosomatids as well. These conserved sequence blocks are ideal targets for PCR primers which can amplify all known minicircle classes from all Leishmania species. The high copy number of the Leishmania minicircles makes them an ideal target for diagnostic tests. The heterogeneity of the variable region has been exploited to discriminate between strains of the same species. Digestion of the kinetoplast DNA with restriction enzymes yields fingerprint patterns that vary considerably within each Leishmania species. Populations that are defined by shared fingerprint patterns are known as schizodemes, and the technique is known as schizodeme analysis. Schizodeme analysis has been widely used in the New World for the classification of Leishmania and Trypanosoma cruzi. The fingerprint patterns themselves provide one of the most specific ways available to identify Leishmania strains (1, 9). kDNA for schizodeme analysis has usually been prepared by differential centrifugation of total DNA from cultured parasites, although it has been shown that kDNA can also be prepared by PCR amplification of purified parasite DNA (3, 15). A nested-PCR-based schizodeme method that permits both very sensitive detection and high-resolution identification of Leishmania parasites directly from clinical samples is presented here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

DNA was prepared from clinical samples collected during a prevalence survey in the Timargara refugee camp. The Timargara refugee camp, in Dir in northwest Pakistan, is a settled camp of 15 years’ standing. There are about 10,000 residents, mostly refugees from the Kabul area of Afghanistan. Small numbers of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis have been observed since 1993. In 1997, a major outbreak occurred, with up to 20% of the population of the camp being affected. Lesions consistent with cutaneous leishmaniasis were cleaned with soap and water and swabbed with ethanol. Samples were taken by using a sterile scalpel to make an incision in the border of the lesion, and a small amount of material was scraped out. The sample was divided between one thin smear on a microscope slide and an Eppendorf tube containing 500 μl of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate (GuSCN)–0.25 M EDTA. Microscope slides were stained with Giemsa stain for direct detection of parasites; GuSCN lysates were stored at 4°C for 1 month until shipment to the United Kingdom at ambient temperature for PCR analysis.

Preparation of DNA samples.

Template DNA was extracted from aliquots of 50, 250, and 100 μl of the GuSCN lysate. Briefly, the sample was bound to diatomaceous earth (Sigma) in the presence of 6 M GuSCN, washed with ethanol and acetone, and eluted with 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4) (6). One microliter of template was used in the first-round PCR. DNA was both prepared from all 20 samples and amplified by PCR at least three times. Each replicate batch was prepared independently from previous batches with fresh sets of reagents. One set of replicates was prepared in a separate laboratory that had not previously been used for Leishmania work. DNA of reference strains was prepared by standard methods (11).

Nested-PCR conditions.

External primers CSB2XF (C/GA/GTA/GCAGAAAC/TCCCGTTCA) and CSB1XR (ATTTTTCG/CGA/TTTT/CGCAGAACG) were designed by identifying suitable regions around conserved sequence blocks 1 and 2 in an alignment of kDNA sequences from Leishmania guyanensis, Leishmania peruviana, L. braziliensis, L. infantum, and Leishmania tropica. The primers were designed to be external to primers 13Z (ACTGGGGGTTGGTGTAAAATAG) (19), which is homologous to conserved sequence block 3 (18), and LiR (TCGCAGAACGCCCCT) (15), which is complementary to conserved sequence block 1. The conserved sequence block 1 is too small for two independent primers, and consequently, the 10 3′ bases of CSB1XR are the same as the 10 5′ bases of LiR. First-round PCR mixtures contained 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 0.01% Tween, 0.4 U of Red Hot Taq (Advanced Biotechnologies, Leatherhead, United Kingdom), and 40 ng each of primers CSB2XF and CSB1XR in a final volume of 20 μl. The cycling conditions were 94°C for 300 s, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s in a Techne Progene thermocycler. One microliter of a 9:1 dilution in water of the first-round product was used as template for the second round in a total volume of 30 μl under the same conditions as those for the first round, except with primers LiR and 13Z. Three microliters of the second-round PCR product was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel to confirm amplification. Positive samples were digested by the addition of 1 U of restriction enzyme, 1.5 μl of restriction enzyme buffer, and 1.4 μl of water to 12.5 μl of PCR product and incubation for 16 h. The restriction digests were separated on a 1.5% 1:1 Nusieve-normal agarose gel to visualize the schizodeme patterns. Samples were tested for the presence of amplifiable human DNA with primers for exon 8 of the single-copy human p53 tumor suppressor gene (8/9LEB, TTGGGAGTAGATGGAGCCT, and 8/9RE, AGTGTTAGACTGGAAACTTT) (12). These primers generate a 445-bp product and were used under the same conditions as those for the nested PCR.

DNA sequencing.

DNA for sequencing was prepared by the nested PCR. The first-round product was reamplified with primers LiR and 13Z in a total volume of 100 μl. Primers and deoxynucleoside triphosphates were removed on an S400 spin column (Pharmacia), the DNA was precipitated with ethanol, and the sample was submitted for cycle sequencing with primers LiR and 13Z on an ABI Prism Model 377 cycle sequencer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to the GenBank database with the accession no. AF032997.

RESULTS

Specificity of PCR.

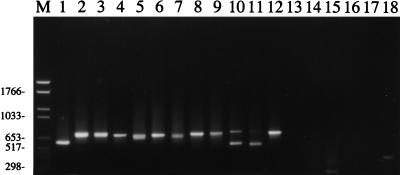

The nested primer set was tested on DNA from a panel of Leishmania species and was found to generate a single major product from representatives of all major species complexes of Leishmania that are infective of humans (Fig. 1). No product was detected from DNA of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense or from the lizard Leishmania parasite Leishmania tarentolae. kDNA from Endotrypanum monterogeii, a closely related parasite of sloths, was amplified. A product of 300 bp was amplified from 10 pg of purified T. cruzi DNA but not from a clinical sample from a T. cruzi-infected patient (Fig. 1, lanes 14 and 15). L. tropica generated the largest Leishmania species PCR product (750 bp) and could be distinguished with care from L. infantum (680 bp) and more easily from Leishmania major (560 bp). It was therefore possible to identify the Old World human-infective Leishmania complexes on the basis of size alone. The New World L. braziliensis complex could not be distinguished from Leishmania mexicana on the basis of size, although the smaller Leishmania amazonensis product was readily identifiable. The E. monterogeii product (780 bp) was slightly larger than the other New World Leishmania species products.

FIG. 1.

Agarose (1.5%) gel of products of the nested PCR on various species of trypanosomatid (lanes 1 to 17) and the PCR with primers for the human p53 gene (lane 18). Lane M, Boehringer Mannheim molecular weight marker set VI; lane 1, L. amazonensis MHOM/BR/73/LV78; lane 2, L. guyanensis MHOM/BR/75/M4147; lane 3, Leishmania panamensis MHOM/NI/87/LS94; lane 4, Leishmania enrietti MCAV/BR/45/L88; lane 5, L. mexicana MNYC/BZ/62/M379; lane 6, Leishmania chagasi (= L. infantum) MHOM/HN/87/HN29; lane 7, L. infantum MHOM/TN/80/IPT1; lane 8, L. tropica MHOM/IR/89/ARD22; lane 9, L. tropica MHOM/PK/97/37\13; lane 10, L. major MHOM/ET/95/FV1 (570 bp); lane 11, L. major MHOM/ET/XX/LV305; lane 12, E. monterogeii MCHO/CR/62/LV88;A9; lane 13, L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/39/TarVI;LV414; lane 14, blood sample collected from patient in Guatemala, positive with T. cruzi-specific primers (8); lane 15, T. cruzi MHOM/BR/78/SilvioX10; lane 16, T. brucei rhodesiense MHOM/UG/XX/WB25;G; lane 17, negative control; lane 18, primers for p53 human gene on clinical sample 1 from Pakistan (MHOM/PK/97/12\3]). Numbers at left indicate size in base pairs.

Sensitivity of PCR.

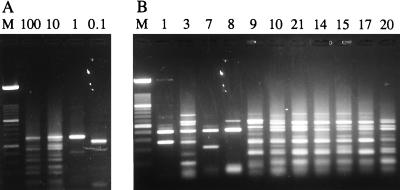

Decimal dilutions from 500 pg to 1 ag of L. infantum MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 total DNA μl−1 were amplified by the nested PCR and digested with HaeIII to determine the limit of detection and the effect of concentration on fingerprint patterns (Fig. 2A). The limit of detection of the L. infantum DNA was 0.1 fg, equivalent to approximately 1/500 of a Leishmania genome (5 × 107 bp, 50 fg), which represents about 100 kDNA minicircles. All products were of similar intensities, suggesting that template concentration was not limiting in the PCR. The fingerprints of the 100- and 10-fg samples were complex and identical to each other; however, the fingerprints of the 1- and 0.1-fg samples consisted of one and two fragments, respectively (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Agarose (1.5% 1:1 Nusieve-normal) gels of schizodemes prepared from kDNA amplified by the nested PCR. (A) Decimal dilution series of L. infantum MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 DNA. The kDNA was amplified from 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 fg of total DNA, respectively, and digested with HaeIII. Lane M, 100-bp-ladder molecular size marker. (B) HaeIII schizodemes of kDNA amplified from clinical samples collected in Pakistan. The lane numbers refer to the sample numbers of parasites in Table 1. Lane M is the same as defined for panel A.

Five replicate PCRs were performed on both the 1.0- and the 0.1-fg samples of MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 DNA, and the products were digested with HaeIII. A strong product was generated in all reactions. All the fingerprint patterns were different, and the sizes of the fragments of three of the five digests of products from 0.1 fg of DNA summed to approximately 680 bp, consistent with their being from a single minicircle class (data not shown). The variability of the fingerprint patterns shows that a different group of minicircle classes was amplified on each occasion and that sometimes only members of a single minicircle class were amplified. Consequently, the PCR template may have contained less than a single parasite genome.

Sequencing of PCR products.

The product of the PCR on 1 fg of MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 3) that had given a single sharp band after digestion was sequenced. A clear sequence signal was obtained with little background, indicating that the sequence had been obtained from a single minicircle class. GenBank was searched for similar sequences with the BLAST program, but no homology was detected with other Leishmania sequences, indicating that this is a novel minicircle class.

Detection of parasites in clinical samples.

The sensitivity of the nested PCR was tested on 20 samples collected from patients in the Timargara refugee camp in Pakistan. The clinical signs and results of PCR and microscopy for each case are shown in Table 1. At least three replicate DNA extractions were prepared from 50-, 250-, and 100-μl aliquots of the 500-μl original sample volume. PCR on these replicate DNA preparations produced 11, 14, and 12 positives, respectively, from the 20 samples. These data suggest that the aliquot size did have some effect on the number of positives. However, one sample (MHOM/PK/97/5\2) was negative from 250 μl, but positive from 100 μl, of sample; this may be a false positive or a consequence of clumping in the sample.

TABLE 1.

Data on clinical cases

| Sample no. | Strain designation | Microscopy resulta | Duration (mo) | Ulcerb | No. of lesions | PCR (+/n)c | Schizodeme patternd,e | Amplification controle,f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MHOM/PK/97/12\3 | − | 12 | − | 4 | 3/4 | NSS− | ++N+ |

| 2 | MHOM/PK/97/8\1 | − | 4 | − | 1 | 0/3 | −−− | −+N |

| 3 | MHOM/PK/97/19\1 | − | 10 | − | 3 | 3/3 | SCC | +++ |

| 4 | MHOM/PK/97/5\2 | + | 4 | − | 1 | 1/3 | −−C | −++ |

| 5 | MHOM/PK/97/12\4 | − | 8 | + | 1 | 0/3 | −−− | +−− |

| 6 | MHOM/PK/97/2E | ND | 12 | + | 2 | 2/3 | −NS | +++ |

| 7 | MHOM/PK/97/2\1 | + | 6 | + | 4 | 3/3 | SCC | −++ |

| 8 | MHOM/PK/97/16\4 | − | 8–9 | + | 6 | 3/3 | SCC | −++ |

| 9 | MHOM/PK/97/37\13 | ND | 12 | ? | 3 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 10 | MHOM/PK/97/16\2 | + | 6–8 | + | 21 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 11 | MHOM/PK/97/3E | ND | 1 | + | 1 | 1/3 | −S− | −++ |

| 13 | MHOM/PK/97/19\7 | − | 12 | − | 2 | 2/3 | −NC | +++ |

| 14 | MHOM/PK/97/12\1 | + | 8 | + | 1 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 15 | MHOM/PK/97/15 | ND | 5 | + | 9 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 16 | MHOM/PK/97/19\2 | − | 10 | − | 2 | 0/3 | −−− | +++ |

| 17 | MHOM/PK/97/E4 | ND | 2 | + | 1 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 18 | MHOM/PK/97/44\1 | − | 8 | + | 4 | 0/3 | −−− | +++ |

| 19 | MHOM/PK/97/12\5 | − | 12 | − | 3 | 0/3 | −−− | ++− |

| 20 | MHOM/PK/97/1E | ND | 9 | + | 1 | 3/3 | CCC | +++ |

| 21 | MHOM/PK/97/11\2 | + | 5 | + | 1 | 2/3 | CC− | +++ |

+ and −, positive and negative, respectively, for Leishmania. ND, not done.

+ and −, presence and absence, respectively, of ulcerated lesions. ?, missing data.

+/n, number of positive PCRs and number of replicates, respectively.

S, simple, <6 fragments; C, complex, >10 fragments; N, not done; −, no PCR product. A simple fingerprint pattern implies that the template contained less than one parasite genome; a complex fingerprint pattern implies that the template contained at least one parasite genome. The five negative samples were from old or treated lesions. Patient 2 (strain MHOM/PK/97/8\1) had been treated with two injections of glucantime before the sample was taken. Patient samples 5, 16, 18, and 19 were from lesions that were at least 8 months old, in which parasites may be very scanty.

Results are presented in replicate order. Replicates were prepared from 50, 250, and 100 μl, respectively, of the 500-μl total sample volume.

The human p53 gene was amplified to determine whether amplifiable DNA was present. The first DNA preparations from patient samples 7 and 8 were positive for Leishmania kDNA but negative for the human p53 gene. N, not done.

All PCR products were the same size as one another and the same size as an L. tropica reference strain, MHOM/IR/89/ARD22 (14) (Fig. 1, lanes 8 and 9); identification was confirmed by the similarity of the schizodeme pattern of all the clinical isolates to that of MHOM/IR/89/ARD22 (data not shown). DNA was prepared from aliquots of each of the 20 patient samples at least three times. Of the 61 DNA preparations, 38 were positive and 23 were negative for Leishmania kDNA by the nested PCR (Table 1). Six of the reactions that were negative for Leishmania kDNA were also negative for the human p53 gene, suggesting that some of the Leishmania negatives may be false negatives (Table 1). Five of the eight reactions which were negative for human DNA were performed on DNA prepared from only 50 μl of the total sample volume of 500 μl; 50 μl is clearly not sufficient, since this sample volume also gave the lowest number of Leishmania-positive reactions (11 of 20). Negative controls were negative in all experiments.

Schizodeme analysis of clinical samples.

The 11 positive samples from the first set of replicates were digested with HaeIII to prepare DNA fingerprints. Seven of the samples had complex fingerprint patterns containing 11 to 12 well-resolved fragments (Fig. 2B; Table 1). Nine of the 12 fragments in the complex fingerprints were present in all samples. A further two or three fragments from a repertoire of four fragments were also present. These variable fragments were not always reproducible in replicate reactions from the same patient sample (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the fingerprints prepared from the L. infantum MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 DNA dilutions were reproducible (Fig. 2A). The four remaining clinical samples each had unique but simpler fingerprints, three of which had only four fragments each (Fig. 2B; Table 1). The simple fingerprints suggest that the nested PCR could detect a fraction of the DNA released from a single parasite.

DISCUSSION

Sensitivity of the nested PCR.

The nested PCR detected extremely small amounts of L. infantum kDNA (0.1 fg), which was shown by sequencing to be derived sometimes from individual minicircle classes. Since the primers are expected to be able to amplify all minicircles present in the template, this implies that only members of one minicircle class were present in the template. This would be the case if there was only one minicircle present in the PCR template; alternatively, some minicircle classes might be preferentially amplified or the classes might be nonrandomly distributed throughout the sample from which the template was taken.

It is unlikely that only single minicircles were present in the template, given the higher-than-expected number of restriction patterns, which were consistent with a single minicircle class, and the absence of negatives that would be expected as a corollary of frequent single minicircles. Preferential amplification of some minicircle classes might occur if the extensive secondary structure found in minicircles reduced the efficiency of amplification of some minicircle classes more than that of others. Nonrandom distribution of minicircles among classes might occur if groups of concatenated minicircles were from the same class.

The nested PCR for detection of Leishmania in clinical samples.

Fifteen patient samples from the Timargara camp were positive in at least one of three replicate DNA preparations. The five patient samples from the Timargara camp that were negative in all three replicates were also negative by microscopy and were from lesions that had been treated or were over 7 months old, in which parasites are frequently very scanty (Table 1). Therefore, these negatives may reflect either a real absence of parasites from the small quantity of material collected by the smears or a lack of sensitivity in the test. Since there is no “gold standard” for detecting Leishmania parasites, it is not possible to distinguish between these two reasons for negative PCRs. Since 6 of the 23 Leishmania-negative DNA preparations were also negative for the p53 single-copy human gene, some of the negative reactions may have been the consequence of low concentrations of patient material, inefficient DNA extraction, or the presence of inhibitors. However, 2 of the 38 Leishmania-positive DNA preparations were negative with the p53 human gene primers; the Leishmania product in these cases gave simple fingerprint patterns (Fig. 1A, lanes 7 and 8) consistent with very low concentrations of target kDNA. The nested PCR can evidently detect at least some of the 10,000 Leishmania kDNA minicircles, even when a single-round PCR cannot detect a single-copy human gene from the patient sample. This confirms the extreme sensitivity of the nested PCR and suggests that the samples that were positive by the p53 human gene primers and negative by the Leishmania primers really did not contain any Leishmania kDNA. This test is now in routine use for the diagnosis and typing of leishmaniasis in our clinical laboratory in Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Single-round PCR on the 120-bp conserved region of Leishmania minicircles is between 1 and 3 orders of magnitude more sensitive than single-round PCR on the approximately 700-bp variable region which was used in this study (2, 19). Single-round PCR on the conserved region may therefore be more suitable for diagnosis in areas where it is not necessary to identify the infecting species; however, it is less suitable for epidemiological studies, since it is not possible to use the product for high-resolution studies by schizodeme analysis.

The clinical appearance of the patients in the Timargara camp from which samples were taken was very variable, as were the number and duration of lesions (Table 1). Given the variability of the pathology and the similarity of the parasites, the outcome of infection with L. tropica in Pakistan may be more dependent on the host response to infection than on the particular strain of parasite involved.

The complex fingerprint patterns prepared from the clinical samples were not fully reproducible on replicate DNA preparations from the same clinical sample. In contrast, the fingerprints prepared from the L. infantum MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 DNA dilutions were reproducible (Fig. 2A), as were fingerprints prepared by digestion of products of single-round PCR on phenol-chloroform-extracted DNA from cultured parasites (15). If this fingerprinting method is to be used in epidemiological studies, at least three replicates from each isolate would be necessary to confirm that the fragments included in the analysis were reproducible.

The simple fingerprint patterns were an artifact caused by operating at the extreme limits of detection and should be excluded from any analysis of populations. Therefore, provided that caution is exercised in interpreting the fingerprint patterns, the nested PCR followed by schizodeme analysis provides the fastest, most specific, and most sensitive method for identifying Leishmania parasite strains available to date and has considerable potential for epidemiological studies.

L. infantum strains from around the Mediterranean are highly variable by schizodeme analysis, and 21 distinct groups have been identified among five zymodemes (1). In contrast, there were no reproducible differences between the L. tropica strains from the Timargara camp in Pakistan with HaeIII and HpaII, and these parasites therefore all belong to the same schizodeme. An L. tropica strain (MHOM/PK/95/05) isolated in another part of Pakistan 2 years previously was distinguished from the samples collected in the Timargara camp by the different mobility of single fragments in both HaeIII and HpaII digests (data not shown). The homogeneous fingerprints of the samples from the Timargara camp are consistent with a recent epidemic spread of a single parasite clone. This is consistent with the significant increase in prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Timargara camp. However, further studies of the variability of L. tropica schizodemes will be required before firm conclusions can be reached about the utility of this method for the study of L. tropica epidemiology. There appears to have been a large increase in cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul since 1992, and significant outbreaks occurred in parts of eastern Afghanistan and in refugee camps in northwest Pakistan in 1997 for the first time (18a). The PCR-based schizodeme technique has considerable potential for elucidating the association between human migration and the spread of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the region. Since the PCR primers described here have amplified kDNA from all human-infective Leishmania species tested, this method should prove valuable as well in other areas where Leishmania is endemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The apparatus used in this study was purchased out of funds donated by Queen Mary’s Roehampton Trust, Wallington, Surrey, United Kingdom, which is gratefully acknowledged.

The p53 gene primers were kindly donated by T. Liloglou, Roy Castle Lung Cancer Research Institute, Liverpool, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelici M C, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L. Study on genetic polymorphism of Leishmania infantum through the analysis of restriction enzyme digestion patterns of kinetoplast DNA. Parasitology. 1989;99:301–309. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000058996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashford D A, Bozza M, Freire M, Miranda J C, Sherlock I, Eulalio C, Lopes U, Fernandes O, Degrave W, Barker R H, Jr, Badaro R, David J R. Comparison of the polymerase chain reaction and serology for the detection of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:251–255. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avila H, Gonçalves A M, Saad Nehme N, Morel C M, Simpson L. Schizodeme analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi stocks from South and Central America by analysis of PCR-amplified minicircle variable region sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;42:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90160-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker D C. DNA diagnosis of human leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1987;3:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Ismail R, Smith D F, Ready P D, Ayadi A, Gramiccia M, Ben-Osman A, Ben-Rachid M S. Sporadic cutaneous leishmaniasis in north Tunisia: identification of the causative agent as Leishmania infantum by the use of a diagnostic deoxyribonucleic acid probe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:508–510. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90087-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boom R, Sol C J A, Salimans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M E, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado O, Guevara P, Silva S, Belfort E, Ramirez J L. Follow-up of a human accidental infection by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis using conventional immunological techniques and polymerase chain-reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:267–272. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn P L, Selgean S, Guillot M. Simplified method for preservation and polymerase chain reaction amplification of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in human blood. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:235–255. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonçalves A M, Nehme N S, Morel C M. Trypanosomatid characterisation by schizodeme analysis. In: Morel C M, editor. Genes and antigens of parasites. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Fundaçao Oswaldo Cruz; 1984. pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim M E, Smyth A J, Ali M H, Barker D C, Kharazmi A. The polymerase chain reaction can reveal the occurrence of naturally mixed infections with Leishmania parasites. Acta Trop. 1994;57:327–332. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly J M. Isolation of DNA and RNA from Leishmania. In: Hyde J E, editor. Protocols in molecular parasitology. Vol. 21. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1993. pp. 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liloglou T, Scholes A G M, Spandidios D A, Vaughan E D, Jones A S, Field J K. p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck predominate in a subgroup of former and present smokers with a low frequency of genetic instability. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4070–4074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meredith S E O, Zijlstra E E, Schoone G J, Kroon C C M, van Eys G J J M, Schaeffer K U, El-Hassan A M, Lawyer P G. Development and application of the polymerase chain reaction for the detection and identification of Leishmania parasites in clinical material. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1993;70:419–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motazedian H, Noyes H, Maingon R. Leishmania and Sauroleishmania: the use of random amplified polymorphic DNA for the identification of parasites from vertebrates and invertebrates. Exp Parasitol. 1996;83:150–154. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noyes H, Chance M, Ponce C, Ponce E, Maingon R. Leishmania chagasi: genotypically similar parasites from Honduras cause both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans. Exp Parasitol. 1997;85:264–273. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao Z, Miles M A, Wilson S M. Detection of parasites of the Leishmania donovani complex by a polymerase chain reaction-solution hybridization enzyme-linked immunoassay (PCR-SHELA) Parasitology. 1995;110:269–275. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos A, Maslov D A, Fernandes O, Campbell D A, Simpson L. Detection and identification of human pathogenic Leishmania and Trypanosoma species by hybridization of PCR-amplified mini-exon repeats. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82:242–250. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray D S. Conserved sequence blocks in kinetoplast minicircles from diverse species of trypanosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1365–1367. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Reyburn, H., and M. Rowland. Unpublished observations.

- 19.Rodgers M R, Popper S J, Wirth D F. Amplification of kinetoplast DNA as a tool in the detection and diagnosis of Leishmania. Exp Parasitol. 1990;71:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]