Abstract

This study was performed to establish optimal nested PCR conditions and a high-yield DNA extraction method for the direct identification of Vibrio vulnificus in clinical specimens. We designed two sets of primers targeting the V. vulnificus hemolysin/cytolysin gene. The target of the first primer set (P1-P2; sense, 5′-GAC-TAT-CGC-ATC-AAC-AAC-CG-3′, and antisense, 5′-AGG-TAG-CGA-GTA-TTA-CTG-CC-3′, respectively) is a 704-bp DNA fragment. The second set (P3-P4; sense, 5′-GCT-ATT-TCA-CCG-CCG-CTC-AC-3′, and antisense, 5′-CCG-CAG-AGC-CGT-AAA-CCG-AA-3′, respectively) amplifies an internal 222-bp DNA fragment. We developed a direct DNA extraction method that involved boiling the specimen pellet in a 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 solution. The new DNA extraction method was more sensitive and reproducible than other conventional methods. The DNA extraction method guaranteed sensitivity as well, even when V. vulnificus cells were mixed with other bacteria such as Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus aureus. The nested PCR method could detect as little as 1 fg of chromosomal DNA and single CFU of V. vulnificus. We applied the nested PCR protocol to a total of 39 serum specimens and bulla aspirates from septicemic patients. Seventeen (94.4%) of the 18 V. vulnificus culture-positive specimens were positive by the nested PCR. Eight (42.1%) of the 19 culture-negative samples gave positive nested PCR results.

Vibrio vulnificus is an estuarine halophilic bacterium that causes fatal primary septicemia and necrotizing wound infections. The primary septicemia occurs following ingestion of raw seafood. V. vulnificus preferentially affects subjects with hepatic diseases, heavy alcohol drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, hemochromatosis, and immunosuppression from corticosteroid therapy, AIDS, or malignancy. The primary septicemia progresses robustly and results in high mortality, more than 50% within a day or two (3, 9, 13, 19, 20, 25).

The genus Vibrio includes more than 30 species, and 12 of these are human pathogens or have been isolated from human clinical specimens. Eight of the 12 human-associated Vibrio species have been isolated from extraintestinal clinical specimens (17). For definitive diagnosis, V. vulnificus should be differentiated from at least seven other extraintestinal Vibrio species. For those patients who die from primary V. vulnificus septicemia, most do so within 2 days of hospital admission (14). Even with the most sophisticated and high-tech equipment or rapid presumptive detection methods that use differential media such as MacConkey agar and thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar, more than 2 days is needed for the definitive identification of V. vulnificus from blood or tissue samples. Clinicians usually start multiple-antibiotic therapy based on their “best guesses” without waiting for culture reports. However, the choices of antimicrobial agents for use against septicemia caused by V. vulnificus or other gram-negative bacteria are dichotomous. The most effective antibiotics recommended for V. vulnificus infections are tetracyclines, especially doxycycline (4, 22). Tetracycline, well known as a bacteriostatic antibiotic, uniquely showed bactericidal activity against V. vulnificus, while expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and aminoglycosides showed minimal antibacterial activities in broth dilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing (22). In an animal experiment, tetracycline also showed superior protective activity relative to that of aminoglycosides and cephalosporins (4). Tetracyclines are seldom prescribed for the treatment of life-threatening septicemias caused by gram-negative bacteria. How early definitive antibiotic therapy can be started for V. vulnificus septicemia based on the identification of the causative organism is the most crucial determinant of the therapeutic outcome. The importance of developing rapid diagnostic measures that can identify the bacterium within hours cannot be overemphasized.

We performed this study with the aim of establishing a nested PCR protocol that gives highly sensitive and specific results within several hours. Nested PCR provides improved sensitivity and specificity in comparison to that of ordinary PCR (11). We designed two sets of primers targeting the cytolysin gene vvh (26) and developed an effective DNA extraction method. Morris et al. proved that the gene was specific for V. vulnificus, and all clinical and environmental isolates of V. vulnificus possesses the gene, as determined by DNA-DNA hybridization (18). By employing these methods, we established a nested PCR protocol that could effectively detect V. vulnificus in clinical specimens such as sera or bulla aspirates.

(Presented in part at the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, New Orleans, La., 15–18 September 1996.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The strains used in this study and their sources are listed in Table 1. They were reidentified biochemically after acquisition from various sources. Brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) was used for the culture of test strains.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used to test the sensitivity and specificity of PCR in identifying V. vulnificus

| Species and strain (n) | Description and/or sourcea |

|---|---|

| Vibrio vulnificus | |

| ATCC 29307 | |

| ATCC27562 | |

| C7184 | CDC; via J. Oliver, UNCC |

| A1402 | CDC; via J. Oliver, UNCC |

| H3308 | CDC; via J. Oliver, UNCC |

| MO6-24/O | Clinical isolate; J. G. Morris, Jr., UMB |

| CVD 752 | Acapsular mutant of MO6-24/O; J. G. Morris, Jr., UMB |

| CNUH (28) | Clinical isolates; Chonnam National University Hospital, Korea |

| WK (10) | Clinical isolates; Wonkwang University Hospital, Korea |

| Vibrio alginolyticus ATCC 17749 | |

| Vibrio cholerae | |

| ATCC 14033 | |

| ATCC 9458 | |

| KNIH | Clinical isolate; Korean National Institutes of Health |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus ATCC 27519 | |

| Vibrio fluvialis ATCC33809 | |

| Vibrio furnissii ATCC 35016 | |

| Vibrio mimicus ATCC 33653 | |

| Vibrio damsela ATCC 33539 | |

| Vibrio hollisae ATCC 33654 | |

| Vibrio harveyi ATCC 14126 | |

| Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966 | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 19215 | |

| Salmonella paratyphi ATCC 11511 | |

| Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 13311 | |

| Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13076 | |

| Shigella flexneri ATCC 9403 | |

| Shigella sonnei ATCC 9290 | |

| Shigella boydii ATCC 8700 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13037 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | |

| Citrobacter freundii ATCC 6750 |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control; UNCC, University of North Carolina, Charlotte; UMB, University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Chromosomal DNA purification.

Chromosomal DNAs of the test strains were purified by a slight modification of the method described by Ausubel et al. (2). Briefly, 3 ml of culture was microcentrifuged and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). Chromosomal DNA was released by adding 100 μg of proteinase K per ml and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and incubating at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, 5 M NaCl solution and cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB)-NaCl (10% CTAB–4.1% NaCl) solution were added to achieve concentrations of 0.7 M NaCl and 1% CTAB sequentially. DNA was extracted by treatment with 24:1 chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and 25:24:1 phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol treatment. The extracted DNA was precipitated with 0.6 volume of isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and dried thoroughly. Purity was determined by calculating A260/A280 ratios, and DNA concentrations were obtained from the A260 values (U2000 spectrophotometer; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

PCR.

We designed a pair of specific primers that does not cross-react with any other genes in GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.). The sequences of the external primers were as follows: sense P1, 5′-GAC-TAT-CGC-ATC-AAC-CG-3′; antisense P2, 5′-AGG-TAG-CGA-GTA-TTA-CTG-CC-3′. The target of the primers is a 704-bp DNA fragment specific for the vvh gene (2,237 nucleotides) from positions 1360 to 2063. The internal primers, sense P3 (5′-GCT-ATT-TCA-CCG-CCG-CTC-AC-3′) and antisense P4 (5′-CCG-CAG-AGC-CGT-AAA-CCG-AA-3′), were designed to amplify the internal 222-bp DNA fragment of the PCR product by the external primers from positions 1460 to 1681 (Fig. 1). They were synthesized with a DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). PCR was performed with a three-bath-type PCR robot (DRBAE 40, FINEPCR; Finemould Precision Ind. Co., Seoul, Korea).

FIG. 1.

Map of PCR-amplified region of the V. vulnificus cytolysin/hemolysin gene (vvh) cloned in plasmid pCVD 702 (26). The external primer set P1-P2 amplifies a 704-bp DNA segment of vvhA, and the internal primer set P3-P4 was designed to detect the internal 222-bp segment. Thick arrows indicate the direction and range of the open reading frames of the vvh genes.

Optimal PCR conditions were fine-tuned by changing the concentration of each ingredient in the reaction mixture (10). Annealing temperatures were adjusted based on the calculated melting temperatures of the oligonucleotide primers. The following was the final constitution of the reaction mixture: 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), 0.5 μM each primer, 250 μM each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (Promega, Madison, Wis.), and 3 (external primers) or 4 (internal primers) mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 50 μl. In some clinical specimens, 15 μg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added to the reaction mixture as Kreader recommended (14). Always, 50 μl of mineral oil were overlaid on the reaction mixtures to prevent evaporation. For every reaction, the reaction mixtures were predenatured at 95°C for 3 min to ensure complete dissociation of the template DNAs. A total of 50 cycles was run, with annealing at 57°C (external primers) or 59°C (internal primers) for 30 s, elongation at 72°C for 1 min, and denaturation at 95°C for 30 s. For the last cycle, the elongation step was prolonged to 10 min to ensure proper extension of bases. For the nested PCR, 5 μl of the first-step reaction mixture with the external primers was collected and added to the second reaction tubes containing internal primers and appropriate concentrations of the other constituents. To rule out false positivity, negative controls with all constituents of the reaction mixture except the template DNA were employed for every experiment.

Detection of PCR product.

A 10-μl portion of the PCR mixture was electrophoresed on a 1.5 or 2.5% agarose gel containing 0.2 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. The gels were run in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (24) at 50 V with standard DNA size markers.

Establishment of an effective single-step DNA extraction method.

To reduce the total processing time and the risk of carryover contamination, an effective single-step DNA extraction method was searched. We tried the following four methods and compared the efficiency of each with that of the method used for the chromosomal DNA purification described above. (i) For DNA extraction by GeneReleaser, a commercial rapid DNA preparation reagent, GeneReleaser (Bioventures, Inc., Murfreesboro, Tenn.), was used as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. (ii) For the boiling-in-water method, pellets or colonies were resuspended in 100 μl of deionized water and heated in boiling water for 15 min. (iii) For the method involving boiling in a 1 mM EDTA solution, pellets or colonies were resuspended in 100 μl of a 1 mM EDTA solution and heated in a microwave oven at high energy for 5 min. (iv) For the method involving boiling in a 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 solution, Triton X-100 was added to a 1 mM EDTA solution to increase the reproducibility of the PCR result. DNA was extracted by the same method as that used for the 1 mM EDTA solution. After treatment with one of these extraction methods, 5 μl of the resulting suspension was added to the reaction mixture as the template.

We employed the method of boiling in water or boiling in a 1 mM EDTA solution because V. vulnificus is highly susceptible to osmotic shock (21, 23). The C7184 strain was harvested at the logarithmic growth phase and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. The bacteria were serially diluted from 1.0 × 108 to single CFU/ml. One-milliliter aliquots of the dilutions were pelleted, and DNAs were extracted by each method described above. After treatment with one of these extraction methods, 5 μl of the resulting suspension was added to the reaction mixture as the template.

Application of the nested PCR protocol to clinical specimens.

When the PCR protocol was applied to the direct identification of V. vulnificus in sera or bulla aspirates from septicemic patients, a 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 solution was used for direct DNA extraction. Blood and bulla aspirate samples were collected and divided into two parts for bacteriological culture and PCR. We followed the clinical criteria of Lee and Kim (16) in selecting cases of probable V. vulnificus septicemia. The volumes of serum and bulla aspirate used for the PCR were about 1.5 to 3 ml and 0.2 to 1 ml, respectively. For the DNA extraction, the serum or bulla aspirate sample was spun down at 15,000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline to minimize contamination by possible PCR inhibitors, resuspended in 100 μl of a 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 solution, and heated in a microwave oven for 5 min.

RESULTS

Specificity and sensitivity of PCR.

The PCR products showed DNA bands of the predicted sizes of 704 and 222 bp with external and internal primers, respectively. The specificity of the primers was tested by performing the PCR with DNAs purified from various strains of bacteria, as listed in Table 1. All of the V. vulnificus strains isolated from either clinical specimens or the environment showed distinct target bands, while other bacteria from different genera and species were negative.

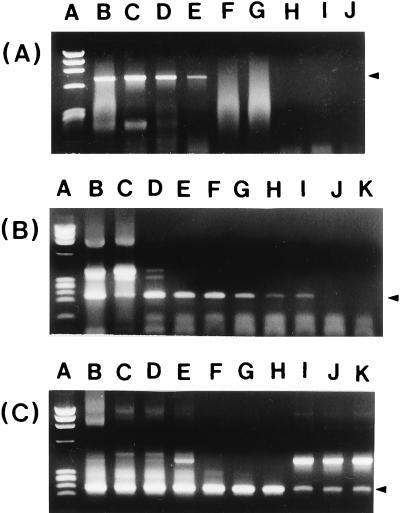

The sensitivity of the primers was tested by performing PCR with serially diluted V. vulnificus C7184 chromosomal DNA. Under optimal conditions, the detection limits of external (P1-P2) and internal (P3-P4) primer sets were 100 pg and 100 fg, respectively. The nested PCR with both sets of primers could detect as little as 1 fg of V. vulnificus DNA (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of PCR with either the P1-P2 (A) or P3-P4 (B) primer set or of nested PCR with a combination of the two sets (C) for detection of purified chromosomal DNA from V. vulnificus C7184. Lanes: A, HaeIII-φ174 DNA markers; B through K, purified chromosomal DNA serially diluted 10-fold from 1 μg to 1 fg.

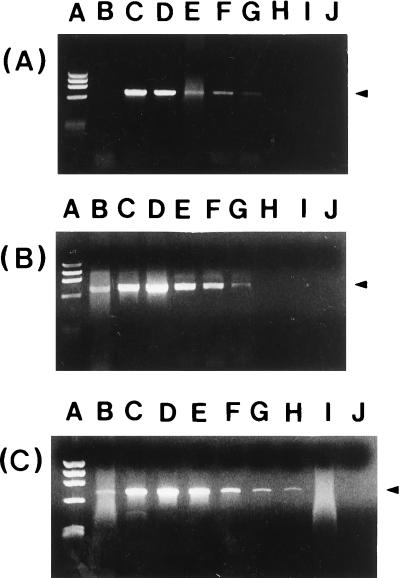

Search for an effective direct DNA extraction method that can be applied to clinical specimens.

By the GeneReleaser method, PCR with the external primer set could detect as few as 103 CFU of V. vulnificus (Fig. 3A). The boiling-in-water method resulted in the same sensitivity (Fig. 3B). The DNA extraction method using a 1 mM EDTA solution provided sensitivity that was 1-log-scale higher than that by the method involving GeneReleaser or boiling in distilled water (Fig. 3C). Although the treatment with GeneReleaser resulted in the most distinct bands after agarose gel electrophoresis, band intensity was stronger when the boiling method with either distilled water or 1 mM EDTA was used.

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of PCR with the P1-P2 primer set for detection of directly extracted chromosomal DNA from V. vulnificus C7184 by the methods involving (A), GeneReleaser (A), boiling in distilled water (B), or boiling in a 1 mM EDTA solution (C). Lanes: A, HaeIII-φ174 DNA markers; B through K, 10-fold serial dilutions of V. vulnificus C7184 from 108 to single CFU. DNA extractions by the GeneReleaser and boiling-in-distilled-water methods gave the same sensitivity, 103 CFU. Direct DNA extraction by boiling bacterial pellets in a 1 mM EDTA solution increased the sensitivity to 102 CFU of V. vulnificus.

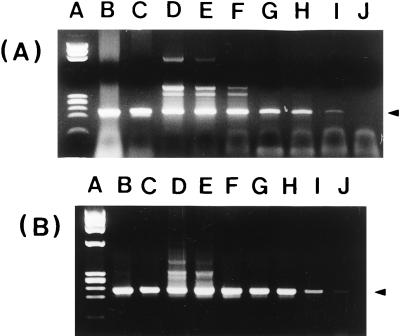

We applied the method involving boiling in a 1 mM EDTA solution to identify V. vulnificus colonies grown on TCBS and other agar plates. The method worked well with most V. vulnificus strains. However, we encountered reproducibility problems with strains showing translucent morphotypes (12). Sometimes, the amplified bands were very faint or invisible. To solve this problem, ethanol and detergents such as Triton X-100, sodium dodecyl sulfate, CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane sulfonate}, Nonidet P-40, and Zwittergent were added empirically to the 1 mM EDTA solution. Those reagents were added in an attempt to solubilize DNA from cellular debris. The DNAs released by osmotic shock seemed to form a complex with cellular debris of translucent morphotypes and do not serve effectively as templates for PCR. The detergents, except Triton X-100, appeared to inhibit the PCR (data not shown). Addition of Triton X-100 resulted in more distinct amplification bands and provided high reproducibility. The most optimal concentration of Triton X-100 was determined to be 0.5% through the fine-tuning experiment using various concentrations (data not shown). Employing this direct DNA extraction method (boiling in 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100), we could detect as few as 10 and single CFU of V. vulnificus by the internal (Fig. 4A) and nested (Fig. 4B) primer sets, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity of PCR with primer set P3-P4 (A) and of nested PCR with primer sets P1-P2 and P3-P4 (B) for the detection of V. vulnificus C7184 when the chromosomal DNA was extracted directly from pure bacterial pellet by boiling in a 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 solution. Lanes: A, HaeIII-φ174 DNA marker; B through J, 10-fold serial dilutions of V. vulnificus C7184 from 108 to single CFU.

Detection of V. vulnificus in mixtures with other bacteria.

The direct DNA extraction method described above worked preferentially for V. vulnificus mixed with Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, which can possibly contaminate clinical specimens during collection. Tenfold serially diluted V. vulnificus C7184 was mixed with 108 CFU of E. coli ATCC 19215 or S. aureus ATCC 25923. Bacterial DNA was extracted from the mixed bacterial pellets by the 1 mM EDTA–0.5% Triton X-100 treatment as described above. The PCR sensitivity for mixed bacterial pellets was the same as that for the control. Using the internal primer set, we could detect 10 CFU of V. vulnificus from the bacterial pellets (data not shown). Most E. coli or S. aureus cells were not destroyed by the DNA extraction method, leaving remnants in the loading wells after agarose gel electrophoresis.

Application of the nested PCR protocol to the direct diagnosis of septicemia.

The established nested PCR protocol, after several steps of fine-tuning as described above, was finally used to diagnose clinical cases. To minimize false positivity and carryover contamination, sample preparation, pre-PCR preparation, thermal cycling, and post-PCR processing were done in separate rooms with separate tools as recommended by standard protocols (6). At every step of the processing, aerosol-resistant tips (Boehringer Mannheim) were used. False positivity was strictly excluded by employing negative controls at every step.

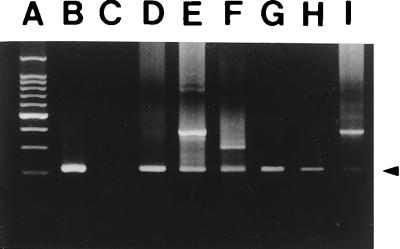

At first, the protocol was applied to serum samples collected from six bacteriologically confirmed septicemia patients. For all of the samples, 222-bp target bands were clearly amplified (Fig. 5). After confirming that the protocol works successfully with clinical specimens, we tried using the nested PCR for actual diagnosis of septicemia cases. Freshly collected serum samples and bulla aspirates were subjected to the nested PCR protocol. A total of 39 samples including the 6 described above were analyzed. The samples were from 35 patients suspected of having V. vulnificus infections. The results of nested PCR were compared with those of bacteriological culture (Table 2). Twenty-seven (69.2%) samples showed positive nested PCR results. Of 16 serum samples from blood culture-positive V. vulnificus septicemia patients, 15 (93.8%) gave positive PCR results, whereas six of 16 (37.5%) culture-negative serum samples were positive by the nested PCR. These six samples were also culture negative for other organisms. Of the five bulla aspirates tested, the two that were culture positive showed positive PCR results (100%) and two of the three (66.7%) that were culture negative gave positive results. An additional two serum samples, collected from patients who died soon after admission, which left no time for blood culture sampling, showed positivity. Twenty-seven patients could be diagnosed as having V. vulnificus septicemia either by bacteriological culture or the nested PCR method. Two of the seven patients that appeared negative for V. vulnificus culture and the nested PCR in both blood and bulla aspirate specimens available were proven to have non-O1 Vibrio cholerae infections. For the remaining five patients, no organism was cultured.

FIG. 5.

Identification of V. vulnificus DNA from serum samples collected from culture-positive septicemia patients by the nested PCR protocol. The arrowhead indicates target bands. Lanes: A, 100-bp DNA ladder; B, positive control (pellet of V. vulnificus C7184); C, negative control (without bacteria); D through I, PCR products from patient serum samples.

TABLE 2.

Identification of V. vulnificus by the nested PCR method and bacteriological culture

| Sample type | Culture results | Nested PCR results (no. of samples)

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| Blooda | Positive | 15 | 1 | 16 |

| Negative | 6 | 10 | 16 | |

| NCb | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Bulla aspirate | Positive | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Negative | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Total | 27 | 18 | 39 | |

Serum was separated for the nested PCR.

NC, not cultured. The patients died before culture samples could be collected.

The total turnaround time from specimen collection to result reporting was less than 6 h. The net time required for specimen processing and experimentation was about 3.5 h: 50 min for serum separation and DNA extraction from pellets centrifuged from the serum, 2 h for two rounds of thermal cycling (1 h each for external and internal targets), and about 40 min for electrophoresis and photographing.

DISCUSSION

This is, to our knowledge, the first report of a PCR diagnosis of clinical V. vulnificus cases. In this study, we designed two sets of primers that detect parts of the V. vulnificus hemolysin (vvh) gene (27) and successfully established a nested PCR and an efficient direct DNA extraction method. Using the nested PCR protocol, we could directly identify V. vulnificus in clinical specimens within several hours.

Definitive diagnosis of bacterial infections requires the identification of causative agents. Phenotypic bacterial identification methods are apt to be influenced by factors such as ingredients of the differential media, culture duration, and residual antibiotic in the specimens, etc. Many Korean septicemia patients suspected of V. vulnificus septicemia were negative by bacterial cultures. In 1989, Lee and Kim reported that of 66 septicemia patients that were admitted to the Chonnam National University Hospital and initially suspected as having V. vulnificus infection from clinical diagnosis, 11 were culture negative (16). Lee and Kim analyzed those septicemia patients with three or more of the following conditions: (i) underlying liver diseases, (ii) obvious history of raw seafood ingestion, (iii) characteristic skin manifestations, and (iv) hypotension on admission. In our study, culture negativity was much higher than that of the previous report. Of our 39 specimens tested, 17 appeared culture negative. The culture negativity could, in most of the cases, be attributed to prior antibiotic treatments. We interpret this increase in culture negativity as the result of increased vigilance of local physicians, who see the patients for the initial visit. Since PCR detects target bacterial DNA rather than the culturable organisms, the nested PCR seemed to identify nonculturable V. vulnificus inhibited by antibiotics.

Our nested PCR protocol provided sensitive diagnosis of V. vulnificus infections within several hours. Bacteriological culture and the PCR method showed high agreement in positivity. Even for culture-negative sera and bulla aspirates, about 40% of the samples showed positive PCR results. Some clinical laboratories are still reluctant to adopt PCR technologies as regular diagnostic procedures because of their extraordinary sensitivity. The most-troublesome problems associated with PCR technologies are false positivity and carryover contamination. We tried every way possible to avoid false positivity and carryover contamination, as recommended in laboratory manuals (6, 7). Of those recommended strategies, the enzymatic elimination method for carryover contamination (7) was not done by us, to shorten the total processing time. The prompt genotypic diagnosis provided by our nested PCR protocol will shorten the delay in providing definitive therapy for V. vulnificus septicemia and complement the sensitivity and accuracy of conventional diagnosis by bacteriological culture.

Recently, several research groups developed PCR protocols targeting the V. vulnificus-specific genes to detect the microorganism in various environmental sources (1, 5, 8, 15). Hill et al. developed a PCR protocol designed to detect the bacterium in oysters after reviewing various DNA extraction methods (8). The sensitivity of their method was so low that overnight incubation of the oyster samples in alkaline peptone water was required for proper detection. Brauns et al. used PCR to detect culturable and nonculturable V. vulnificus cells in seawater (5). They showed that more DNA was required for detection of nonculturable than culturable cells and proposed a time-efficient two-step PCR method. Hill et al. (8) tried to establish a PCR method for the identification of V. vulnificus in artificially contaminated oysters. They needed an overnight enrichment culture of artificially seeded oyster homogenates for effective PCR detection. Arias et al. (1) reported a nested PCR method for rapid detection of the bacterium in fish, sediments, and water. They increased the sensitivity to as little as 10 fg of the bacterial DNA. Using their method, they could detect as few as 12 to 120 cells in artificially seeded glass eel homogenates without enrichment. Lee et al. (15) reported a PCR method in combination with an enrichment medium and a DNA extraction method, which could detect 10 CFU of V. vulnificus inoculated in homogenates of small octopus, one of the major sea animals associated with V. vulnificus septicemia in Korea. However, none of the researchers tried to fine-tune their protocols for the rapid identification of V. vulnificus in clinical specimens. We successfully established a nested PCR protocol along with a direct DNA extraction method for V. vulnificus which provides high sensitivity and specificity. We shortened the time required for diagnosis to less than 6 h. In conclusion, we suggest that the nested PCR protocol is promising as a rapid and sensitive diagnostic measure for V. vulnificus septicemia and should be used as a complementary tool to conventional culture methods.

The present study showed some novel phenomena that require explanation. Often, smears of DNA fragments were observed at the DNA concentration of the sensitivity cutoff or at a concentration 1-log-scale lower than the cutoff, as shown in Fig. 2A and 3C. These fragments could be clearly differentiated from primer dimers or nonspecific bands. Smears can be frequently observed when the template DNA concentration used is highly excessive. However, this was not the case because the smears appeared at sufficiently lower template DNA concentrations, around the detection limit. In addition, the nested PCR often produced unexpected bands of about 400 bp between the external 704-bp and internal 200-bp target bands (Fig. 2 and 5). A smaller band of about 300 bp was observed in a clinical specimen (Fig. 5). To test whether these bands were a nonspecific amplification product or a specific derivative of the target (inner 222-bp) sequence, a Southern blot analysis of the nested PCR product was performed by using a 32P-labelled 222-bp fragment as a probe. Only the specific target fragments (222 and 704 bp) and the novel 400-bp bands appearing between the two target bands were hybridized by the probe under high-stringency conditions (data not shown). This result suggests that the bands in lanes I, J, and K of Fig. 2C and 5 are the specific reaction product of the nested PCR. However, the reason they have a higher-intensity appearance than the target 222-bp band remains to be elucidated by analyzing their DNA sequences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the 1995 Basic Medical Research Fund from the Ministry of Education (S.S.C.) and grant KOSEF 96-0402-01-3 (J.H.R. and S.H.C.) from the Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias C, Garay R, E, Aznar R. Nested PCR method for rapid and sensitive detection of Vibrio vulnificus in fish, sediments, and water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3476–3478. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3476-3478.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake P A, Merson M H, Weaver R E, Hollis D G, Heublein P C. Disease cause by a marine Vibrio. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197901043000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowdre J H, Hell J H, Cocchetto D M. Antibiotic efficacy against Vibrio vulnificus in the mouse: superiority of tetracycline. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;225:595–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brauns L A, Hudson M C, Oliver J D. Use of polymerase chain reaction in detection of culturable and nonculturable Vibrio vulnificus cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2651–2655. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.9.2651-2655.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieffenbach C W, Dragon E A, Dveksler G S. Setting up a PCR laboratory. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartley J L, Rashtchian A. Enzymatic control of carryover contamination in PCR. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill W E, Keasler S P, Trucksess M W, Feng P, Kaysner C A, Lampel K A. Polymerase chain reaction identification of Vibrio vulnificus in artificially contaminated oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:707–711. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.3.707-711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hlady W G, Klontz K C. The epidemiology of Vibrio infections in Florida, 1981–1993. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1176–1183. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innis M A, Gelfand D H. Optimization of PCRs; In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Snisky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson D P, Hayden J D, Quirke P. Extraction of nucleic acid from fresh and archival material. In: McPherson M J, Quirke P, Taylor G R, editors. PCR: a practical approach. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim C M, Jeong K C, Rhee J H, Choi S H. Thermal-death times of opaque and translucent morphotypes of Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3308–3310. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3308-3310.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klontz K C, Lieb S, Schriber M, Janowski H T, Baldy L M, Gunn R A. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections: clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida, 1981–1987. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:318–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-4-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreader C A. Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin or T4 gene 32 protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J Y, Eun J B, Choi S H. Improving detection of Vibrio vulnificus in Octopus variabilis by PCR. J Food Sci. 1997;62:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S H, Kim S J. Epidemiologic and microbiologic study in 64 clinically suspected cases of V. vulnificus infections. Korean J Int Med. 1989;36:820–830. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin J C. Vibrio. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris J G, Jr, Wright A C, Roberts D M, Wood P K, Simpson L M, Oliver J D. Identification of environmental Vibrio vulnificus isolated with a DNA probe for the cytotoxin-hemolysin gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:193–195. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.1.193-195.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paik K W, Moon B, Park C W, Kim K T, Ji M S, Choi S K, Rew J S, Yoon C M. Clinical characteristics of ninety-two cases of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Korean J Infect Dis. 1995;27:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S D, Shon H S, Joh N J. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia in Korea: clinical and epidemiologic findings in seventy patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:397–403. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70059-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhee J H, Cho S H, Chung S S. Bactericidal effect of osmotic shock against Vibrio vulnficus. J Korean Soc Microbiol. 1987;22:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee J H, Choi S N, Chung S S. Bactericidal activity of tetracyline against Vibrio vulnificus. J Korean Assoc. 1987;30:769–777. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee J H, Lee S E, Shin S H, Shin B A, Chung S S. A basic study for the development of effective preventive measure against Vibrio vulnificus septicemia—bactericidal mechanism of osmotic shock. J Korean Soc Microbiol. 1997;32:183–199. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacket C D, Brenner R, Blake P A. Clinical features and epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:558. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, Wright A C, Kaper J B, Morris J G., Jr The cytolysin gene of Vibrio vulnificus: sequence and relationship to the Vibrio cholerae El Tor hemolysin gene. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2706–2709. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2706-2709.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]