Abstract

Background and aims

This paper aimed to evaluate the use of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The effects of acupuncture and behavioural therapy, two nonpharmalogical interventions, on social function in ASD patients are still controversial. This meta-analysis investigated the impact of these two treatments and compared their effects.

Methods

Seven electronic databases were systematically searched to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the use of acupuncture or behavioural therapy for ASD. A meta-analysis was carried out using Review Manager 5.4 software. Continuous data are reported as mean differences (MDs) or standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An assessment of methodological quality using the Cochrane risk-of-bias (ROB) tool for trials was carried out. The Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) was applied to evaluate the quality (certainty) of evidence for results regarding social function indicators.

Results

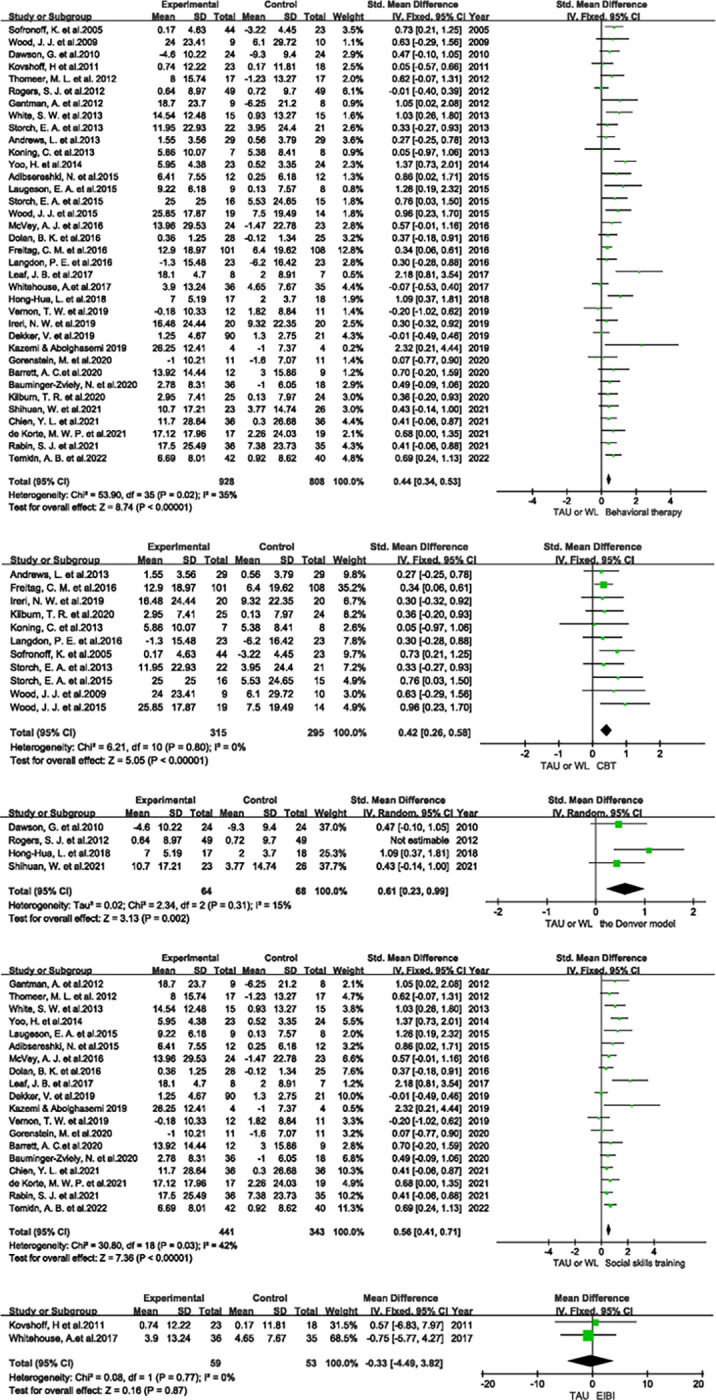

Thirty RCTs on acupuncture and 36 on behavioural therapy were included. Compared with the control condition, body acupuncture (SMD: 0.76, 95% CI: [0.52, 1.01]; low certainty), modern acupuncture technology (SMD: 0.84, 95% CI: [0.32, 1.35]; low certainty), cognitive behavioural therapy (SMD: 0.42, 95% CI: [0.26, 0.58]; high certainty), the Denver model (SMD: 0.61, 95% CI: [0.23, 0.99]; moderate certainty) and social skills training (SMD: 0.56, 95% CI: [0.41, 0.71]; moderate certainty) improved social functioning.

Conclusion

Behavioural therapies (such as CBT, the Denver model, social skills training), improved the social functioning of patients with ASD in the short and long term, as supported by high- and moderate-quality evidence. Acupuncture (including scalp acupuncture, body acupuncture and use of modern acupuncture technology) also improved social functioning, as supported by low- and very low-quality evidence. More high-quality evidence is needed to confirm the effect of acupoint catgut embedding and Early Intensive Behavioural Intervention (EIBI).

1 Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a global health problem. In 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that among American 8-year-olds, 1 in every 44 have ASD. These statistics represent a 23% increase in prevalence over the past two years. This increased prevalence (i.e., the prevalence in 2021) is 3.39 times higher than the prevalence of autism first reported by the CDC in 2000. In China, survey data show that children with ASD (prevalence rate of 1%) account for 36.9% of children with intellectual disabilities [1]. Studies from some European countries have also shown a considerable increase in estimated ASD prevalence recently [2]. The increased prevalence among Eastern and Western countries imposes financial burdens on families and on society. For example, a 2018 Chinese survey showed that nearly 30 000 RMB was spent on children with ASD in the past 12 months [3]. Social dysfunction is one of the two leading indicators of ASD, arising from impairments in several functional domains [4]. Unfortunately, these impairments are exacerbated rather than ameliorated over development [5]. Nonpharmacological interventions are considered a safe treatment for ASD.

Nonpharmacological therapy, including behavioural therapy and acupuncture, is effective as a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) [6–9]. The European Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP) recommends behavioural interventions for ASD that are developmentally based and involve social communication therapies and interventions based on administered behaviour evaluation, including Early Intensive Behaviour Intervention (EIBI), Naturalistic Developmental Behavioural Intervention (NDBI), the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM), social skill programs, and cognitive behavioural theory (CBT).

Most meta-analyses have examined the overall effect of acupuncture on ASD rather than specific aspects such as its effect on social function [8, 10]; hence, a systematic evaluation and quantitative analysis of clinical evidence for the use of behavioural therapy and acupuncture for ASD and their effects on social function is needed. This study aimed to identify the short- and long-term effects of acupuncture and behavioural therapy on social function among ASD patients. The benefits of behavioural therapy and acupuncture were also compared.

2 Methods

The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on November 3rd, 2021, and revised on May 26th, 2022 (registration number: CRD42021284512).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows for studies identified in the literature review: (1) included participants with a diagnosis of ASD, regardless of age, sex, or race; (2) included at least one of the eight kinds of intervention type; (3) included a control group that underwent regular psychotherapy, therapy as usual, registration on a waitlist, or no intervention; (4) included indexes of social function or outcomes of social function, assessed before and after treatment; (5) was an RCT; and (6) was published in Chinese or English. Studies were excluded if they (1) applied specific or rarely used psychotherapy in the control group or (2) failed to report sufficient data to calculate the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD). The eligibility criteria listed above are also displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Participants with a diagnosis of ASD, regardless of age, sex, or race | |

| Intervention | Included at least one of the eight kinds of intervention type (scalp acupuncture, body acupuncture, modern acupuncture technology, acupoint catgut embedding, cognitive behavioural therapy, the Denver model, social skills training, or early intensive behavioral intervention) | |

| Comparison | A control group that underwent regular psychotherapy, therapy as usual, registration on a waitlist, or no intervention | Applied specific or rarely used psychotherapy in the control group |

| Outcome | Indexes of social function or outcomes of social function, assessed before and after treatment | Failed to report sufficient data to calculate the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) |

| Study design | RCT | |

| Other | Written in Chinese or English. |

2.2 Data sources and search strategies

The databases searched included PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), PsycINFO, and CNKI and WanFang (databases of Chinese medical journals). RCTs on acupuncture and behavioural therapy were identified (details shown in the figure in S1 Material in S1 File). The literature search spanned from database inception to April 26th, 2022.

2.3 Study selection and literature search

All articles were identified and screened by two independent reviewers (Zhili Yu (ZY) and Chenyang Tao (CT)) using NoteExpress; any disagreements were resolved through discussion. If the articles were inaccessible, researchers contacted the authors to obtain them; if the authors were unavailable, the articles were excluded.

2.4 Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (ZY and CT) extracted the following information from the included studies: first author, publication year, country of origin, study population, age range or mean age, numbers of cases and controls, treatment methods for each group (a brief overview of the types of interventions included is shown in S2 Material Table 2 in S1 File), sample size of the study population in the last intervention, social function indicators, intervention duration, follow-up period duration and social function outcomes (mean and SD). If the indexes of social function encompassed two or more scales or two or more indexes were related to the same indicator of social function, we chose the scale or index most frequently used in other studies to control for known sources of heterogeneity.

2.5 Quality assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated by the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias (ROB) tool, which assesses the risk of bias in seven aspects on three grades: low, high, and unclear risk of bias. Finally, an overall ROB rating was obtained for each included study. Disagreements over the ROB between the reviewers (ZY and CT) were resolved through discussion with another author (Peiming Zhang (PZ)). A table presenting the risk of bias was generated with Revman 5.4 software.

2.6 Effect measures

Pretreatment, posttreatment, and follow-up data were extracted. The meta-analysis assessed differences between pretreatment and posttreatment as well as between pretreatment and follow-up. The social function indicators included eight positive scales (the Griffith Mental Development Scale (GMDS), Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM), Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL), Social Life Ability Scale(SM), Social Competence with Peers Questionnaire (SCPQ), Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge (TASSK), Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ), and Social Skills Rating Scale (SSRS)) and eight negative scales (the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC), Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS), Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS), and Contextual Assessment of Social Skills (CASS)). If a study failed to report all necessary data, we attempted to contact the authors of the study; if the authors were not reached, we excluded the study. Brief overviews of the scales measuring social function indicators are provided in S2 Material Table 1 in S1 File.

2.7 Quality of evidence

For studies included in the meta-analysis, GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2022) was used to determine the quality of evidence according to the Cochrane-recommended GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [11]. If limitations were identified, the quality (certainty) of evidence was downgraded according to the guidelines.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 software. Changes in social functioning were computed using MD with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) if the outcome measures were the same across studies and SMDs with 95% CIs when the outcome measures differed across studies. If only baseline and final scores were reported, a formula [12] was adopted to determine the change in social function. Regarding changes in social functioning measured with negative scales (i.e., on which higher scores reflected worse social functioning), the change was multiplied by -1 to standardize the direction of effects with that of the positive scales [12]. Moreover, all outcome data were transformed to the MD and SMD as appropriate, following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The I2 test was used to analyse the heterogeneity of the pooled studies. Fixed-effects models were used unless I2>50%; in this case, a random-effects model was used, and the causes of heterogeneity were explored through subgroup or sensitivity analyses. If the quantity of included studies was adequate (n≥10), a funnel plot was constructed to assess publication bias [10].

3 Results

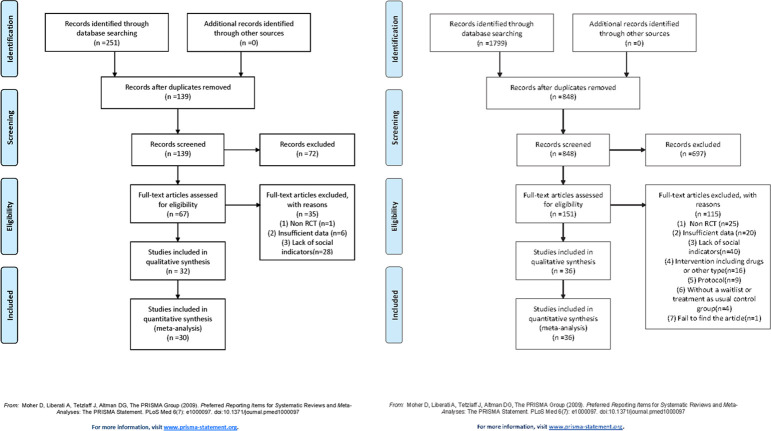

The literature search of the seven databases initially identified 1799 behavioural therapy RCTs and 251 acupuncture RCTs. Of these, 951 behavioural therapy and 112 acupuncture RCT duplications were excluded; 697 behavioural therapy and 71 acupuncture publications were removed after review of the title and abstract, and 115 behavioural therapy and 37 acupuncture articles were excluded after review of the full text. Finally, 36 behavioural therapy and 32 acupuncture studies were included. The screening steps are displayed in Fig 1A and 1B.

Fig 1.

a. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of included studies on acupuncture. b. PRISMA flowchart of included studies on behavioural therapy.

All included studies were RCTs. The characteristics of the participants, interventions, controls, and outcomes are described below.

Thirty-two studies administered acupuncture plus regular psychotherapy in the treatment group (Table 2). Participant ages ranged from 1 to 18 years old. Regarding the control group, all articles administered regular psychotherapy. Only two studies used sham or nonpoint acupuncture as a control group; these studies administered electroacupuncture to the treatment group. The most common social function indicator used in acupuncture studies was the ABC. Although the intervention durations were variable among acupuncture studies, most administered 70 to 80 sessions.

Table 2. Summary of treatment and treatment-related information from included studies on acupuncture.

| Authors, years | Age of Participants | Sample(T/C) | Intervention(C) | Intervention(T) | Social Outcome indicators | Intervention length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yanrong, G.et al., 2021 | Age 4–12 years | 25/25 | Analysis behavior therapy | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 60 sessions |

| Huijie, L. 2022 | Age 3–7 years | 31/31 | Auditory integration training | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 36 sessions |

| Lianjun, L.2017 | Age 2.5–6.7 years | 43/40 | Music therapy | C+ scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 30 sessions |

| Yanna, H.2018 | Age 1–2 years | 40/40 | Treatment as usual+ Jiao’s scalp needle | C+ Lin’s scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 30 sessions |

| Lina, Y. et al.2021 | Under 12 years | 53/53 | Treatment as usual | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 18 sessions |

| Yamei, L. et al., 2019 | Age 1.3–6.6 years | 35/35 | Language training | C+ scalp acupuncture | ATEC | 80 sessions |

| Ping, W.2021 | Age 2–7 years | 40/40 | Discrete Trial Teaching | C+ scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 77 sessions |

| Huiqin & Yushun, 2019 | Age 1–11 years | 40/40 | Behavioral therapy | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 12 sessions |

| Jin, Y.et al.2016 | Age 3–6 years | 40/40 | Treatment as usual | C+ scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 60 sessions |

| Renhua, M. et al.2017 | Age 1–6 years | 32/32 | Treatment as usual | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 28 sessions |

| Hongtao, Z. et al.2018 | Age 1–11 years | 45/45 | Behavioral therapy | C+ scalp acupuncture | ABC | 12 sessions |

| Nuo, L. et al., 2017 | Age 2–6 years | 45/45 | Music therapy+ structured teaching | C+ body acupuncture | Gesell | 90 sessions |

| Kong, F. et al., 2018 | Under 14 years | 30/30 | Language training + behavior training + cognitive training | C+ body acupuncture | Gesell | 102 sessions |

| Feng, G. et al., 2019 | Age 2–12 years | 30/30 | Language training + behavior training + multi-sense training | C+ body acupuncture | ATEC | 77 sessions |

| Yanli, W. et al., 2020 | Age 2–6 years | 35/35 | Language training + behavior training + critical response training | C+ body acupuncture | ABC | 75 sessions |

| Guo-Xiang, Z. et al.2020 | Average age 5±1 years | 55/55 | Behavior analysis+ language training+ music therapy+ multi-sense training | C+ body acupuncture | CARS | 90 sessions |

| Weili, D. et al., 2020 | Age 3–6 years | 43/43 | Treatment as usual | C+ body acupuncture | ATEC | 77 sessions |

| Ying, T.2022 | Age 5–10 years | 50/50 | Treatment as usual | C+ body acupuncture | PedsQL | 90 sessions |

| Longsheng, H. et al.2021 | Age 3–7 years | 25/25 | Applied behavioral analysis + TEACCH | C+ needle-embedding therapy+ Jin’s three-needle therapy | ABC+CARS | 60 sessions |

| Lan, R. et al., 2021 | Age 2–8 years | 54/54 | Treatment as usual | C+ body acupuncture | ABC | 80 sessions |

| Jingang, Z.2021 | Age 2–9 years | 44/44 | Interest-based floor play therapy | C+ body acupuncture | ABC | 60 sessions |

| Caixia & Yongchao 2020 | Age 1–7 years | 25/25 | Treatment as usual | C+ body acupuncture | SM | 28 sessions |

| Wen & Xiangdong, 2020 | Control: 2–9 years; Treatment: 22–41 years | 35/35 | Structured teaching pattern | C+ body acupuncture | ABC | 72 sessions |

| Bing-xu, J. et al.2020 | Age 3–6 years | 30/30 | Conductive education+ language training+ music therapy | C+ acupoint catgut embedding | ABC | 15 sessions |

| Wen-Liu, Z. et al.2021 | Age 3–6 years | 30/30 | Language training+ applied behavior analysis+ multi-sense training | C+ acupoint catgut embedding | Gesell | 18 sessions |

| C+ scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 128 sessions | ||||

| Wong & Chen2010 | Age 3–18 years | 30/25 | Non-point electroacupuncture+ treatment as usual | Electroacupuncture+ treatment as usual | WeeFIM | 14 sessions |

| Wang, C. N. et al.2007 | Age 3–9 years | 30/30 | Behavioral therapy | C+ Electroacupuncture | ABC | 80 sessions |

| Surapaty, I. A. et al.2020 | Age 2–6 years | 23/23 | sensory–occupational integrative therapy+placebo acupuncture |

sensory–occupational integrative therapy+verum laser acupuncture |

WeeFIM | 18 sessions |

| Wanqiong, Z.2022 | Age 5–11 years | 35/35 | Treatment as usual | C+ Electroacupuncture | ABC | 72 sessions |

| Ningxia, Z.et al., 2015 | Age 2.5–6 years | 30/30 | Treatment as usual | C+ Electroacupuncture | ABC | 72 sessions |

| Nuo, L. et al., 2011 | Age 2–6 years | 30/40 | Music therapy+ conductive education | C+ scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 60 sessions |

| Yong, Z. et al., 2015 | Age 1–2 years | 33/32 | Treatment as usual+Jiao scalp needle | C+ Lin scalp acupuncture | Gesell | 45 sessions |

*ABC: Autism Behavior Checklist; ATEC: Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist; CARS: Childhood Autism Rating Scale; PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; SM: social life ability scale; WeeFIM: Functional Independence Measure for Children

Thirty-six studies administered behavioural therapy (Table 3). Participant age ranged from 1.5 to 65 years old. The control group in behavioural therapy studies most frequently involved a waitlist control. The SRS was the most commonly used social function indicator. The intervention durations less variable among behavioural therapy studies than acupuncture studies; most studies administered 14 to 16 sessions. Only four studies provided follow-up results after treatment, and all administered behavioural therapy. The length of the follow-up period ranged from 6 weeks to 2 years.

Table 3. Summary of treatment and treatment-related information from included studies on behavioural therapy.

| Authors, years | Age of Participants | Sample(T/C) | Intervention(C) | Intervention(T) | Social Outcome indicators | Intervention length | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews, L. et al., 2013 | Age 7–12 years | 29/29 | Waitlist control | CBT | SCPQ | Ten sessions | |

| Langdon, P. E. et al.2016 | Age 17–65 years | 23/23 | Waitlist control | CBT | Social Phobia Inventory | 24 sessions | |

| Kilburn, T. R. et al., 2020 | Age 8–14 years | 25/24 | Waitlist control | the Cool Kids ASD program | CATS | Ten sessions | |

| Koning, C. et al.2013 | Age 10–12 years | 7/8 | Waitlist control | CBT-based social skills intervention | SRS | 15 sessions | |

| Sofronoff, K. et al.2005 | Age 10–12 years | 21/23 | Waitlist control | CBT (children only) | SCAS-P | Six sessions | Six weeks |

| CBT (child + parents) | |||||||

| Freitag,C.M.et al.2016 | Age 8–20 years | 101/108 | Treatment as usual | SOSTA-FRA | SRS | 12 sessions | Three months |

| Ireri, N. W. et al.2019 | Age 5–24 years | 20/20 | Waitlist control | MASSI | SRS | 20 sessions | |

| Wood, J. J. et al., 2015 | Age 11–15 years | 19/14 | Waitlist control | BIACA | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Wood, J. J. et al., 2009 | Age 7–11 years | 9/10 | Waitlist control | CBT | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Storch, E. A. et al.2015 | Age 11–16 years | 16/15 | Treatment as usual | BIACA | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Storch, E. A. et al.2013 | Age 7–11 years | 22/21 | Treatment as usual | CBT | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Dawson, G. et al.2010 | Age 1.5–2.5 years | 24/24 | the assess-and-monitor | ESDM | VANS | 1042 sessions | |

| Hong-Hua, L. et al.2018 | Age 2–5 years | 17/18 | Treatment as usual | ESDM | ABC | 77 sessions | |

| Rogers, S. J. et al.2012 | Age 1–2 years | 49/49 | Treatment as usual | ESDM | VANS | 12 sessions | |

| Shihuan, W. et al.2021 | Age 1–3 years | 23/26 | Waitlist control | ESDM | Gesell | 24 sessions | |

| Gantman, A. et al.2012 | Age 1.5–2 years | 9/8 | Waitlist control | The UCLA PEERS | SRS | 14 sessions | |

| Vernon, T. W. et al.2019 | Age 1.5–4.7 years | 12/11 | Waitlist control | the Pivotal Response Intervention for Social Motivation | VANS | 26 sessions | |

| Leaf, J. B. et al.2017 | Age 3–7 years | 8/7 | Waitlist control | Social skills groups | SRS | 32 sessions | |

| McVey, A. J. et al.2016 | Age 18–28 years | 24/23 | Waitlist control | PEERS | SRS | 14 sessions | |

| Dolan, B. K. et al.2016 | Age 11–16 years | 28/25 | Waitlist control | PEERS | CASS | 14 sessions | |

| Thomeer, M. L. et al. 2012 | Age 7–12 years | 17/17 | Waitlist control | a comprehensive psychosocial intervention |

SRS | Six sessions | |

| Yoo, H. et al.2014 | Age 12–18 years | 23/24 | Waitlist control | Korean PEERS® Treatment | TASK | 14 sessions | |

| Laugeson, E. A. et al.2015 | Age 18–24 years | 9/8 | Waitlist control | PEERS | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Temkin, A. B. et al.2022 | Age 8–12 years | 42/40 | Treatment as usual | Secret Agent Society | SSQ | Nine sessions | |

| Rabin, S. J. et al.2021 | Age 12–17 years | 36/35 | Waitlist control | PEERS | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| White, S. W. et al., 2013 | Age 12–17 years | 15/15 | Waitlist control | MASSI | SRS | 20 sessions | |

| Gorenstein, M. et al.2020 | Age 18–45 years | 11/11 | Waitlist control | Job-Based Social Skills Program | SRS | 15 sessions | |

| Kazemi & Abolghasemi 2019 | Average age 11.88±2.29 years | 4/4 | No intervention | Play-based empathy training | SRS | 18 sessions | |

| Dekker, V. et al.2019 | Age 9.6–13 years | 26/26 | Treatment as usual | Social Skills Training | SSRS | 15 sessions | |

| Social Skills Training- parent and teacher involvement | |||||||

| De Korte, M.W.P.et al.2021 | Age 9–15 years | 17/19 | Treatment as usual | Pivotal Response Treatment | SRS | 12–20 sessions | Eight weeks |

| Chien, Y. L. et al.2021 | Age 18–45 years | 36/36 | Treatment as usual | PEERS | SRS | 16 sessions | |

| Bauminger-Zviely, N. et al.2020 | Age 8–16 years | 18/18 | Treatment as usual | Conversation | VANS | 60 sessions | |

| 18 | Collaboration | ||||||

| Barrett, A. C.et al.2020 | Age 1.5–4.5 years | 12/9 | Waitlist control | Pivotal Response Treatment | Parent-child play interaction videos | 6.81h/week, six months total | |

| Adibsereshki, N. et al.2015 | Age 7–12 years | 12/12 | Regular school program | Theory of Mind | SSRS | 15 sessions | |

| Kovshoff, H et al.2011 | Age 6.5–8 years | 23/18 | Treatment as usual | EIBI | VANS | Two years | Two years |

| Whitehouse, A.et al., 2017 | Average age: Control 40.25±8.41 months; Treatment 39.36±8.50 months | 36/35 | Treatment as usual | C+ TOBY(app based an app-based learning curriculum) | VANS | 180 sessions |

*CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; SCPQ: Social Competence with Peers Questionnaire; CATS: Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale; SRS: Social Responsiveness Scale; SCAS: Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale; SOSTA-FRA: Social Skills Training Autism–Frankfurt; MASSI: Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention; BIACA: Behavioural Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism; ESDM: Early Start Denver Model; VABS: Vinland Adaptive Behavior Scales; UCLA PEERS: University of California at Los Angeles Program for the Education and Endowment of Relational Expertise; CASS: Contextual Assessment of Social Skills; TASSK: Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge; SSQ: Social Skill Questionnaire; SSRS: Social Skills Rating Scale.

The overall risk of bias of the included studies followed the suggested framework and was categorized as follows: high risk (2.90%), unclear risk (75.00%), and low risk (22.06%) (S3 Material Table 1 and Fig 3 in S1 File). More specifically, regarding random sequence generation, 32 studies were rated as "low risk”, and two studies were rated as "high risk”. Regarding allocation concealment, 14 studies were rated as "low risk”. Regarding the blinding of participants and personnel, two studies were rated as "low risk", and the other 66 were rated as "high risk”. Regarding blinding of outcome assessment, 17 studies were rated as “low risk”. All studies were rated as “unclear risk" regarding incomplete outcome data. Regarding other biases, one study was rated as "high risk", and the other 68 studies were rated as "low risk" (details are provided in S3 Material Figs 1 and 2 in S1 File). Specific sources of risk are outlined in S3 Material Table 2 in S1 File.

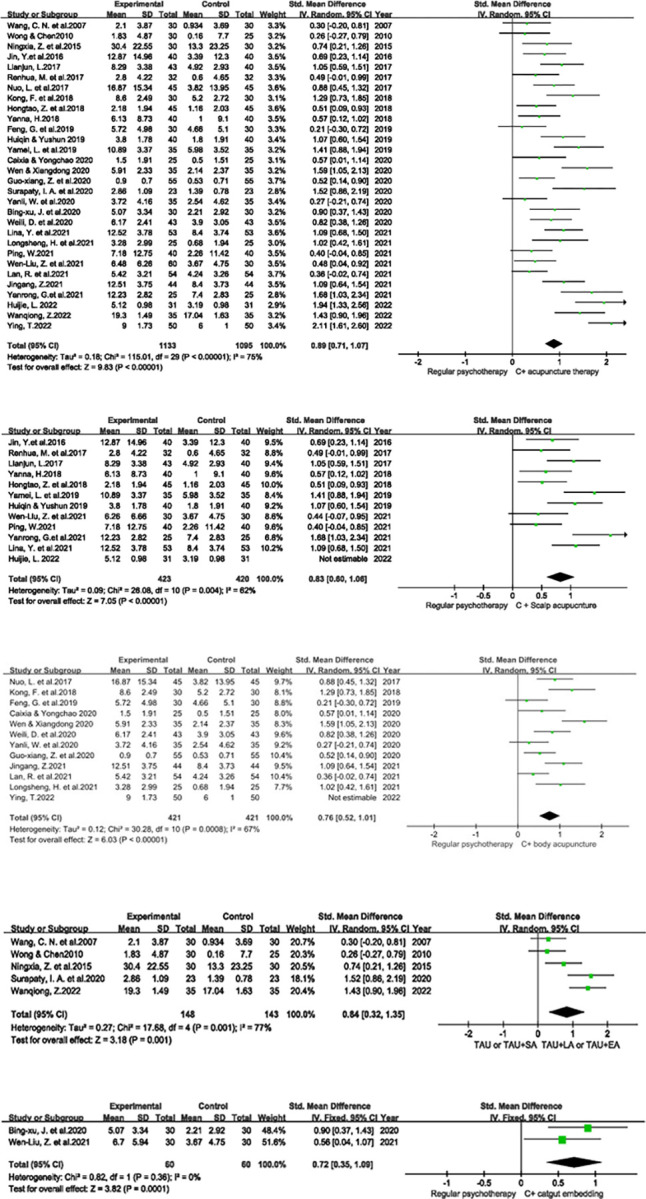

The evaluation of the overall effect of acupuncture included 30 studies; overall, acupuncture improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.71, 1.07). A random-effects model was applied for analysis given the considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75%); a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 2A).

Fig 2.

a Forest plot of the overall effect of acupuncture. *C: Control. b Forest plot of the effect of scalp acupuncture. c Forest plot of body acupuncture. d Forest plot of the effect of modern acupuncture technology. *TAU: treatment as usual; EA: electroacupuncture; LA: laser acupuncture; SA: sham acupuncture. e Forest plot of the effect of acupoint catgut embedding.

Analysis of the effect of scalp acupuncture included eleven studies; scalp acupuncture improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.60, 1.06). A random-effects model was applied given the moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 62%); a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 2B).

Analysis of the effect of body acupuncture included eleven studies; body acupuncture improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.52, 1.01). A random-effects model was applied given the moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 67%); a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 2C).

Analysis of the effect of modern acupuncture technology included five studies; modern acupuncture technology improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.32, 1.35). A random-effects model was applied given the considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 77%); a significant difference was observed (P = 0.001) (Fig 2D).

Analysis of the effect of acupoint catgut embedding included two studies; acupoint catgut embedding improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.09). As there was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), a fixed-effects model was applied, and a significant difference was observed (P = 0.0001) (Fig 2E).

Analysis of the overall effect of behavioural therapy included 36 studies; behavioural therapy improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.53). A fixed-effects model was applied as there was little heterogeneity (I2 = 35%), and a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 3A).

Fig 3.

a Forest plot of the overall effect of behavioural therapy. *WL: Waitlist. b Forest plot of the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy. c Forest plot of the effect of the Denver model. d Forest plot of the effect of social skills training. e Forest plot of the effect of Early Intensive Behavioural Intervention.

Analysis of the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) included eleven studies; CBT improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0. 42, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.58). There was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%); thus, a fixed-effects model was applied, and a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 3B).

Among CBT studies, Langdon, P. E. et al. (2016) evaluated social functioning with the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), in which the variables reflect adverseness to the participants. As a result, SPIN scores were multiplied by -1 during meta-analysis. Sofronoff, K. et al. (2005) assessed social functioning with the parent-report version of the SCAS (SCAS-P); changes in SCAS-P scores were multiplied by -1 for the same reason. Furthermore, this RCT was a 3-arm experiment, in which the treatment group was divided into CBT (children only) and CBT (children + parents); thus, the data were combined using the same formula mentioned above.

Analysis of the effect of the Denver model included three studies; the Denver model improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.99). There was little heterogeneity (I2 = 15%); thus, a fixed-effects model was applied, and a significant difference was observed (P = 0.002) (Fig 3C).

Dawson, G. et al. (2010) evaluated social outcomes with the VABS and showed declines in the treatment and control groups. As higher VBAS scores reflect worse social functioning, we multiplied these scores by -1.

Analysis of social skills training included 19 studies; social skills training improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.71). There was little heterogeneity (I2 = 42%); thus, a fixed-effects model was applied, and a significant difference was observed (P<0.00001) (Fig 3D).

Seven studies assessed social functioning with the SRS, CASS, or VABS; higher scores on these scales reflects worse social functioning. Thus, we multiplied these scores by -1 during analysis.

Analysis of the effect of EIBI included two studies; EIBI did not improve social functioning to a greater extent than the control condition (MD -0.33, 95% CI: -4.49, 3.82). There was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%); thus, a fixed-effects model was applied, but no significant difference was observed (P = 0.87) (Fig 3E).

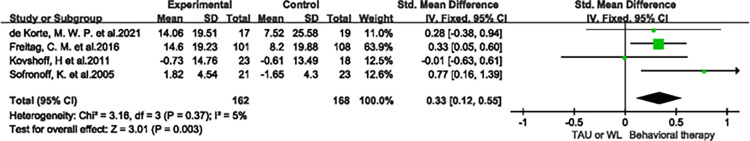

Analysis of the long-term effect of behavioural therapy included four studies; long-term behavioural therapy improved social function to a greater extent than the control condition (SMD: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.55). There was little heterogeneity (I2 = 5%); thus, a fixed-effects model was applied, and a significant difference was observed (P = 0.003) (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Forest plot of the long-term effect of behavioural therapy.

Kovshoff, H et al. (2011) and Sofronoff, K. et al. (2005) (in a control group) reported detrimental increases in scores after treatment; therefore, we multiplied these scores by -1 during analysis.

Nearly all studies compared acupuncture plus psychotherapy with regular psychotherapy. In other words, they adopted acupuncture as a complementary therapy. An insufficient number of studies compared the effects of acupuncture and behavioural treatment directly; thus, no analysis was conducted.

Next, the source of heterogeneity was investigated. Five studies were removed. Specifically, comparison of the effects of scalp acupuncture plus psychotherapy with those of regular psychotherapy involved the initial exclusion of two high-risk studies. Subsequently, another study was excluded, which decreased I2 by 10%. One study was excluded when comparing the effects of body acupuncture plus psychotherapy with those of regular psychotherapy; I2 decreased by 14%. In the comparison of the effects of the Denver model and those of the control condition, 1 study was excluded, and I2 decreased by 45%.

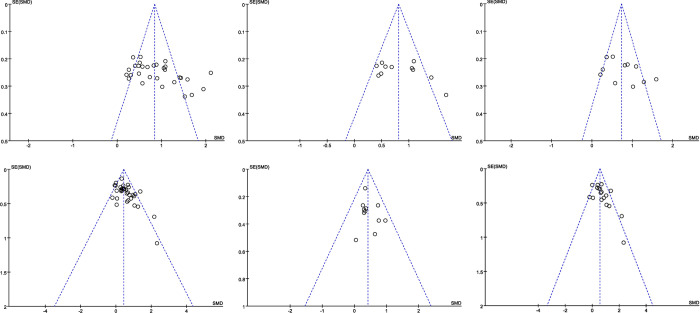

Regarding the types of intervention included, more than 10 studies applied acupuncture, behavioural therapy, scalp acupuncture, body acupuncture, CBT, and social skills training; the other interventions were applied in fewer than 10 studies. Funnel plot examination was performed for the six intervention types listed above. The funnel plots of studies on acupuncture, scalp acupuncture, body acupuncture, CBT, and social skills training showed some asymmetry, suggesting the presence of publication bias. (Fig 5A–5F).

Fig 5.

a Funnel plot of all acupuncture studies. b Funnel plot of scalp acupuncture studies. c Funnel plot of body acupuncture studies. d Funnel plot of all behavioural therapy studies. e Funnel plot of cognitive behavioural therapy studies. f Funnel plot of social skills training studies.

The overall certainty of evidence for the effects of acupuncture was very low. Among the types of acupuncture, the quality of evidence for the effects of scalp acupuncture was very low, that for body acupuncture and modern acupuncture technology was low, and that for acupoint catgut embedding was moderate. The overall certainty of evidence for the effects of behavioural therapy was moderate. Among the types of behavioural therapy, the quality of evidence for the effect of CBT was high, that for the Denver model and social skill intervention was moderate, and that for EIBI was low. The quality of evidence for the long-term effect of behavioural therapy was moderate (details are provided in S4 Material Table 1 in S1 File).

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis summarized the effects of acupuncture [13–44] and behavioural therapy [45–80] on social functioning in patients with ASD in a total of 68 RCTs. The following methods improved social functioning and had moderate- or high-quality evidence: acupoint catgut embedding (moderate certainty), behavioural therapy (moderate certainty), CBT (high certainty), the Denver model (moderate certainty), social skills training (moderate certainty) and the long-term effect of behavioural therapy (moderate certainty). Among them, acupoint catgut embedding (SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.09) significantly improved scores on social function indicators. In contrast, behavioural therapy (SMD: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.53), CBT (SMD: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.58), the Denver model (SMD: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.99), social skills training (SMD: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.71) and long-term behavioural therapy (SMD: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.55) had moderate effects on social functioning. Although modern acupuncture technology and body acupuncture had low-quality evidence regarding improvements in social functioning, they both resulted in significant improvements in social functioning (modern acupuncture technology, SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.09; body acupuncture, SMD: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.52, 1.01).

In the investigation of the source of heterogeneity, 5 studies [13, 22, 24, 26, 57] were excluded. Two of these studies [22, 24] were rated as “high risk” for both random sequence generation and overall risk of bias [11]. The other three studies [13, 26, 57] were identified as possible sources of heterogeneity through sensitivity analysis. The potential causes of heterogeneity in these studies are as follows. Huijie, L. (2022) [13] used a different control group (auditory integration training) than the other included studies on scalp acupuncture. Ying, T. (2022) [26] used adjunct acupoints based on syndrome differentiation rather than primary acupoints plus adjunct acupoints for acupuncture, in contrast to other included studies on body acupuncture. Moreover, the authors adopted PedsQL scores as a social function indicator; this also differs from related studies. Rogers, S. J. et al. (2012) [57] had the shortest intervention duration among the 4 ESDM studies. Additionally, they did not observe a significant difference between the two groups, in contrast to the other three ESDM studies. Finally, heterogeneity in acupuncture studies remained after sensitivity analysis, but the potential cause was not identified in subgroup analysis. The possible reasons are as follows. The sample sizes of the included acupuncture studies were smaller than those in some of the behavioural studies. Since most acupuncture methods follow the theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which emphasizes individualized treatment, the selection of acupoints and needle manipulation may have varied, inducing variation in the reported results.

Compared to similar previous meta-analyses, the present has some advantages regarding improved classification methods and inclusion of a greater variety of intervention types. Among meta-analyses on the effect of acupuncture on ASD, acupuncture effects were usually categorized according to scales; little attention was given to the overall effect of acupuncture [8, 10]. Our meta-analysis concentrated on effects on social functioning and categorized acupuncture studies according to the intervention types. Regarding the effect of behavioural interventions on ASD, our meta-analysis included a wider range of behavioural therapy techniques than previous meta-analyses on social skills training [81] and focused on the effects on social functioning, which few previous CBT, Denver model, or EIBI meta-analyses examined [82–84].

This systematic review and meta-analysis has the following practical implications. (1) The effect of behavioural therapy (except EIBI) was moderate, and the long-term effect of behavioural therapy was small. Quality of evidence for these two effects were moderate and high, respectively. The former result is similar that of other meta-analyses, including one on children and adolescents with a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders that was published in JAMA the year before last [85]. Our meta-analysis more definitely indicates that ASD patients with social deficits could benefit from behavioural therapy. When ASD patients show signs of social impairment, behavioural therapy should be considered during the development of the clinical treatment strategy. (2) There was a significant effect of acupuncture and of the four acupuncture types when applied as adjuvant therapy (CAM). Additionally, in light of American Psychological Association (APA) guidance and a previous acupuncture meta-analysis, acupuncture as CAM may be added when the main symptom of ASD patients is social impairment. (3) The quality of evidence of most effects of acupuncture was low or very low. More rigorously designed RCTs are needed to elucidate the effects of acupuncture on social functioning in ASD patients. (4) The vast majority of acupuncture studies examined the overall effect on ASD rather than the effect on specific aspects such as social function or communication. Developing specific acupuncture points to treat specific symptoms of ASD may be a promising research direction.

The strengths of this study are as follows. (1) This meta-analysis included both acupuncture and psychotherapy studies, which are critical components of nonpharmacological interventions for ASD. (2) This study focused on social functioning in ASD patients, and social function-related data were classified and included in subgroup analysis according to the detailed intervention type. Therefore, the results of this study provide some support for the formulation of treatment plans. (3) This study evaluated the long-term effect of behavioural therapy, supporting early interventions for ASD. (4) Regarding the statistical methodology, the pretreatment-posttreatment difference was used to minimize the effect of baseline data on the results. Moreover, social function-related scales were included when possible and combined with the SMD. However, this study also has some limitations. (1) Given limited time and human resources, we focused on only the effect of the eight intervention types on social functioning in ASD according to studies published in Chinese or English. (2) Few studies applying acupoint catgut embedding or EIBI met the inclusion criteria; thus, it was difficult to evaluate the effect of the two treatments on social functioning among patients with ASD. (3) There were insufficient eligible studies to compare the effects of acupuncture and behavioural therapy on social functioning. Further advanced and multidimensional studies or more in-depth analyses, such as network meta-analyses, are needed to explore the efficacy of these two critical nonpharmacological interventions and to determine differences in the effectiveness of these two intervention types for improving social functioning.

5 Conclusion

Behavioural therapy, including CBT, the Denver model, social skills training and long-term behavioural therapy, enhanced social functioning in patients with ASD, as supported by high- and moderate-quality evidence. Acupuncture, including scalp, body, and modern acupuncture technology, also improved social functioning in patients with ASD, as supported by very low- and low-quality evidence. More high-quality evidence is needed to confirm the effect of acupoint catgut embedding and EIBI on social functioning in ASD.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Report on the development of autism education and rehabilitation industry in China.: Beijing Normal University Publishing Group; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiarotti F, Venerosi A. Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Worldwide Prevalence Estimates Since 2014. Brain Sci. 2020;10(5). doi: 10.3390/brainsci10050274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou W, Wu K, Chen S, Liu D, Xu H, Xiong X. Effect of Time Interval From Diagnosis to Treatment on Economic Burden in Families of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.679542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee SB. Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: American Academy of Pediatrics 2020 Clinical Guidelines. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(10):959–62. 10.1007/s13312-020-2003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picci G, Scherf KS. A Two-Hit Model of Autism: Adolescence as the Second Hit. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015. p. 349–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ameican Academy of Pediatrics. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuentes J, Hervás A, Howlin P, ESCAP AWP. ESCAP practice guidance for autism: a summary of evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2020;30(6):961–84. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01587-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee B, Lee J, Cheon J, Sung H, Cho S, Chang GT. The Efficacy and Safety of Acupuncture for the Treatment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid-Based Compl Alt. 2018;2018:1–21. doi: 10.1155/2018/1057539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia YN, Gu JH, Wei QL, Jing YZ, Gan XY, Du XZ. [Effect of scalp acupuncture stimulation on mood and sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2021;46(11):948–52. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.20210276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Peng J, Qiao F, Cheng W, Lin G, Zhang Y, et al. Clinical Randomized Controlled Study of Acupuncture Treatment on Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid-Based Compl Alt. 2021;2021:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2021/5549849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions | Cochrane Training.; 2022.

- 12.Higgins J, Thomas J. the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.: Wiley; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijie L. Observation on the curative effect of transhead acupuncture combined with visual and auditory training on autism. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2022;38(03):488–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lina Y, Chunyan Z, Yu L, Jianrong P. Study on the Effect of Scalp Acupuncture Combined with Behavioral Therapyin Children with Autism. Chinese Journal of Social Medicine. 2021;38(02):236–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamei L, Yingying M, Jiajia Z, Zhe Z. Clinical observation of scalp acupuncture combined with speech training on speech rehabilitation of autistic children. Journal of Pediatrics of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2019;15(03):71–4. 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2019.03.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huiqin H, Yushun Z. Clinical Observation on 40 Cases of Infantile Autism Treated by Scalp Acupuncture Combined with Behavioral Therapy. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy. 2019;28(05):89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Xusheng G, Hongmei W, Qingrui Z. 40 cases of children with autism treated by head acupuncture combined with parent-child games and rehabilitation training. Traditional Chinese Medicinal Research. 2016;29(02):54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanrong G, Haoqiang Z, Xiaodi Z. Effect of scalp acupuncture combined with behavioral analysis therapy on joint attention and social communication ability of children with autism. World Latest Medicine. 2021;21(40):101–3. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-3141.2021.40.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renhua M, Shanshan X. Observation on curative effect of acupuncture and moxibustion combined with comprehensive rehabilitation training on children with autism. Practical Clinical Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. 2017;17(12):132–3. 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2017.12.083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hongtao Z, Zhixiong L, Jinhua H, Yujuan X. Effects of scalp acupuncture combined with behavioral therapy on therapeutic effect, psychology and quality of life of parents in children with autism. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2018;33(15):3451–4. 10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2018.15.28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lianjun L. Clinical Study on Interactive Scalp Acupuncture Therapy for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2017;36(11):1303–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yong Z, Bingxu J, Zhenhuan L. Clinical Study on Needling LIN’s Three Temporal Acupoints for Children with Autism. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2015;34(08):754–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanna H. Therapeutic effect of scalp acupuncture on children with autism. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2018;34(07):833–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuo L, Bingxu J, Jieling L, Zhenhuan L. Scalp acupuncture therapy for autism. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion. 2011;31(08):692–6.21894689 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ping W. Observation on the effect of Xingnao Kaiqiao scalp acupuncture therapy on children with autism. Journal of Frontiers of Medicine. 2021;11:182–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ying T. Efficacy Observation of Acupuncture Combined with Rehabilitation Training for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2022;41(04):387–91. 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2022.04.0387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longsheng H, Yu H, Pin G, Ping O, Wanyu Z, Jingrong W, et al. Curative effect of Jin’s three needles therapy on core symptoms and sleep disorder in children with mild 0 to 0 moderate autism spectrum disorder. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research. 2021;32(10):2447–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lan R, Jiao-wei GU, Yong W, Chen C. Effects of acupuncture combined with rehabilitation training on language communication disorders and abnormal behaviors in autism children. Hainan Medical Journal. 2021;32(9):1148–50. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2021.09.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jingang Z. Therapeutic effect of acupuncture at Du Mai point combined with interest oriented floor play therapy on children with autism. Capital Medicine. 2021;28(24):148–50. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8257.2021.24.066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caixia C, Yongchao L. Application Effect of Acupuncture Combined With Comprehensive Rehabilitation Training on Children With Autism. China Health Standard Management. 2020;11(9):81–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9316.2020.09.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wen T, Xiangdong Y. Effect analysis of acupuncture combined with structured education mode in the treatment of children with autism. Journal of Qiqihar Medical College. 2020;41(12):1505–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-1256.2020.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuo L, Jie-ling L, Zhen-huan L, Yong Z, Bin-xu J, Wen-jie F, et al. Clinical observation on acupuncture at thirteen ghost acupoints for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2017;15:344–8. 10.1007/s11726-017-1025-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong F, Hu D, Yuan Q, Zhou W, Li P. Efficacy of acupuncture on children with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(12):13775–80. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan-li W, Qing S, Hui-chun Z, Li-ye S, Chao G. Clinical Study of Du Xue Dao Qi Needling Method for Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2020;39(07):856–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng G, Ning-xia Z, Ning-bo Z, Wen-tao J, Kai G. Clinical effect of Tiaoshen acupuncture combined with special education and training in treatment of speech disorder in children with autism spectrum disorder. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy. 2019;34(12):5987–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo-xiang Z, Xiao-qian Y, Jing-jiang Q. Efficacy Observation of Acupuncture at the Governor Vessel Combined with Rehabilitation Training for Autism. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2020;39:1570–5. 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2020.13.1053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weili D, Wei L, Bingxiang M. Effects of acupuncture intervention on core symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder. Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020;35(05):527–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bing-xu J, Nuo L, Yong Z, Xu-guang Q, Zhen-huan L, Yang Y, et al. Effect of acupoint catgut embedding therapy on joint attention and social communication in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion. 2020;40(02):162–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen-Liu Z, Fang L, Zhi-Juan T, Fei-Fei W, Yun S. Effects of Acupoint Catgut Embedding on Cognition and Language Function in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Based on the Theory of Regulating Mental with Pivot. Journal of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2021;38(05):954–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wanqiong Z. Clinical observation of electroacupuncture combined with rehabilitation training for children with autism. Guangming Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2022;37(02):300–3. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ningxia Z, Feng G, Wentao J, Ningbo Z, Bingcang Y, Yani F, et al. Clinical Study of the Intervention on Abnormal Behavior in the Children with Autism Treated with Head Electroacupuncture and Special Education. World Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2015;10(08):1104–6. 10.13935/j.cnki.sjzx.150822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang CN, Liu Y, Wei XH, Li LX. [Effects of electroacupuncture combined with behavior therapy on intelligence and behavior of children of autism]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27(9):660–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surapaty IA, Simadibrata C, Rejeki ES, Mangunatmadja I. Laser Acupuncture Effects on Speech and Social Interaction in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Med Acupunct. 2020;32(5):300–9. doi: 10.1089/acu.2020.1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong VC, Chen WX. Randomized controlled trial of electro-acupuncture for autism spectrum disorder. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15(2):136–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S. A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2005;46(11):1152–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Van Dyke M, Decker K, Fujii C, et al. Brief report: effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on parent-reported autism symptoms in school-age children with high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(11):1608–12. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0791-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, Nadeau JM, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, et al. The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2013;52(2):132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koning C, Magill-Evans J, Volden J, Dick B. Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy-based social skills intervention for school-aged boys with Autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spect Dis. 2013;7(10):1282–90. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews L, Attwood T, Sofronoff K. Increasing the appropriate demonstration of affectionate behavior, in children with Asperger syndrome, high functioning autism, and PDD-NOS: A randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spect Dis. 2013;7(12):1568–78. 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS, Dane BF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(3):174–81. doi: 10.1002/da.22332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Alessandri M, Fujii C, Renno P, Laugeson E, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and clinical anxiety: a randomized, controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2015;46(1):7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freitag CM, Jensen K, Elsuni L, Sachse M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Schulte-Rüther M, et al. Group-based cognitive behavioural psychotherapy for children and adolescents with ASD: the randomized, multicentre, controlled SOSTA-net trial. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2016;57(5):596–605. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langdon PE, Murphy GH, Shepstone L, Wilson ECF, Fowler D, Heavens D, et al. The People with Asperger syndrome and anxiety disorders (PAsSA) trial: a pilot multicentre, single-blind randomised trial of group cognitive-behavioural therapy. Bjpsych Open. 2016;2(2):179–86. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ireri NW, White SW, Mbwayo AW. Treating Anxiety and Social Deficits in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Two Schools in Nairobi, Kenya. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(8):3309–15. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilburn TR, Sørensen MJ, Thastum M, Rapee RM, Rask CU, Arendt KB, et al. Group based cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomised controlled trial in a general child psychiatric hospital setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;available from: 10.1007/s10803-020-04471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, Vismara L, Winter J, Fitzpatrick A, et al. Effects of a Brief Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)-Based Parent Intervention on Toddlers at Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2012;51(10):1052–65. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong-Hua LI, Chun-Li LI, Di G, Xiu-Yu P, DU Lin, Fei-Yong J. Preliminary application of Early Start Denver Model in children with autism spectrum disorder. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 2018;20:793–8. 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shihuan W, Xiaobing Z, Yuanyuan Z, Haitao Z, 陈凯云. Effect of early intervention Denver model on toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care. 2021;29(12):1300–3. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gantman A, Kapp SK, Orenski K, Laugeson EA. Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(6):1094–103. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1350-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomeer ML, Lopata C, Volker MA, Toomey JA, Lee GK, Smerbeck AM, et al. Randomized clinical trial replication of a psychosocial treatment for children with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools. 2012;49(10):942–54. [Google Scholar]

- 62.White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, et al. Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skill Intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(2):382–94. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoo H, Bahn G, Cho I, Kim E, Kim J, Min J, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Korean Version of the PEERS (R) Parent-Assisted Social Skills Training Program for Teens With ASD. Autism Res. 2014;7(1):145–61. 10.1002/aur.1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laugeson EA, Gantman A, Kapp SK, Orenski K, Ellingsen R. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Social Skills in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The UCLA PEERS (R) Program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(12SI):3978–89. 10.1007/s10803-015-2504-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adibsereshki N, Nesayan A, Asadi GR, Karimlou M. The Effectiveness of Theory of Mind Training On the Social Skills of Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Iran J Child Neurol. 2015;9(3):40–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McVey AJ, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, Karst JS, Casnar CL, et al. A Replication and Extension of the PEERS® for Young Adults Social Skills Intervention: Examining Effects on Social Skills and Social Anxiety in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(12):3739–54. 10.1007/s10803-016-2911-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dolan BK, Van Hecke AV, Carson AM, Karst JS, Stevens S, Schohl KA, et al. Brief Report: Assessment of Intervention Effects on In Vivo Peer Interactions in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(6):2251–9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leaf JB, Leaf JA, Milne C, Taubman M, Oppenheim-Leaf M, Torres N, et al. An Evaluation of a Behaviorally Based Social Skills Group for Individuals Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(2):243–59. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2949-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dekker V, Nauta MH, Timmerman ME, Mulder EJ, van der Veen-Mulders L, van den Hoofdakker BJ, et al. Social skills group training in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2019;28(3):415–24. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1205-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vernon TW, Holden AN, Barrett AC, Bradshaw J, Ko JA, McGarry ES, et al. A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial of an Enhanced Pivotal Response Treatment Approach for Young Children with Autism: The PRISM Model. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2358–73. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03909-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kazemi F, Abolghasemi A. Effectiveness of play-based empathy training on social skills in students with autistic spectrum Disorders. Arch Psychiatr Psych. 2019;21(3):71–6. 10.12740/APP/105490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bauminger-Zviely N, Estrugo Y, Samuel-Magal K, Friedlin A, Heishrik L, Koren D, et al. Communicating Without Words: School-Based RCT Social Intervention in Minimally Verbal Peer Dyads with ASD. J Clin Child Adolesc. 2020;49(6):837–53. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1660985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gorenstein M, Giserman-Kiss I, Feldman E, Isenstein EL, Donnelly L, Wang AT, et al. Brief Report: A Job-Based Social Skills Program (JOBSS) for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(12):4527–34. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04482-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barrett AC, Vernon TW, McGarry ES, Holden AN, Bradshaw J, Ko JA, et al. Social responsiveness and language use associated with an enhanced PRT approach for young children with ASD: Results from a pilot RCT of the PRISM model. Res Autism Spect Dis. 2020;71. 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chien YL, Tsai WC, Chen WH, Yang CL, Gau SSF, Soong WT, et al. Effectiveness, durability, and clinical correlates of the PEERS social skills intervention in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: the first evidence outside North America. Psychol Med. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Korte MWP, van den Berk-Smeekens I, Buitelaar JK, Staal WG, van Dongen-Boomsma M. Pivotal Response Treatment for School-Aged Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(12):4506–19. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-04886-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rabin SJ, Laugeson EA, Mor-Snir I, Golan O. An Israeli RCT of PEERS: Intervention Effectiveness and the Predictive Value of Parental Sensitivity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2021;50(6):933–49. 10.1080/15374416.2020.1796681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Temkin AB, Beaumont R, Wkya K, Hariton JR, Flye BL, Sheridan E, et al. Secret Agent Society: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Transdiagnostic Youth Social Skills Group Treatment. Res Child Adoles Psy. 2022;available from: 10.1007/s10803-020-04471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kovshoff H, Hastings RP, Remington B. Two-Year Outcomes for Children With Autism After the Cessation of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention. Behav Modif. 2011;35(5):427–50. doi: 10.1177/0145445511405513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whitehouse A, Granich J, Alvares G, Busacca M, Cooper MN, Dass A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of an iPad-based application to complement early behavioural intervention in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2017;58(9):1042–52. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gates JA, Kang E, Lerner MD. Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:164–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reichow B, Hume K, Barton EE, Boyd BA. Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD009260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009260.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tiede G, Walton KM. Meta-analysis of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23(8):2080–95. doi: 10.1177/1362361319836371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perihan C, Burke M, Bowman-Perrott L, Bicer A, Gallup J, Thompson J, et al. Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Reducing Anxiety in Children with High Functioning ASD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(6):1958–72. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03949-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Darling SJ, Goods M, Ryan NP, Chisholm AK, Haebich K, Payne JM. Behavioral Intervention for Social Challenges in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama Pediatr. 2021;175(12):e213982. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.