Abstract

BACKGROUND: Infliximab (IFX) was one of the first tumor necrosis factor inhibitors developed to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and has transformed the treatment and management of many chronic inflammatory diseases. Large-scale studies in the real-world setting on the utilization patterns of IFX biosimilars are limited.

OBJECTIVE: To conduct a scoping review of observational studies investigating the switching and discontinuation outcomes of the IFX biosimilars in patients with RA.

METHODS: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in 3 databases (ie, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science). This review identified observational studies that examined switching and/or discontinuation outcomes of IFX biosimilar products in adult patients with RA. Studies published in English between 2015 and 2020 were included. Studies that did not include either switching or discontinuation patterns of IFX biosimilars, had a pooled result for biologics, or were nonobservational were excluded. Extracted data were summarized using descriptive statistics.

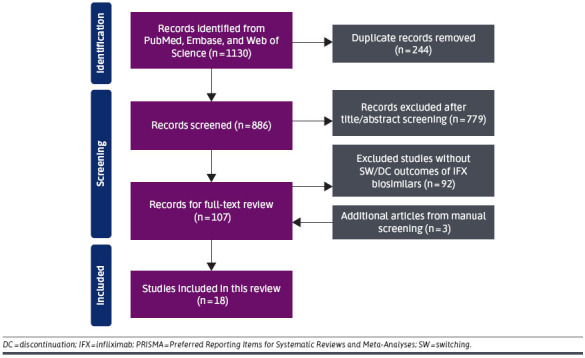

RESULTS: The initial literature search yielded 1,130 studies. With 244 duplicate articles removed and 779 excluded after title and abstract screening, the search resulted in 107 studies for full-text screening. 18 articles were included in this review. 13 countries were represented in the included studies, with most studies originating in a European country and only one article from the United States. Discontinuation rates of IFX biosimilars were reported by 14 studies and varied substantially from 8.3% to 87.0%. 4 studies (22%) directly compared discontinuation rates between IFX reference and biosimilar. Switching rates, similarly, had a great variance from 4% to 81.5%; only 4 articles described rates specifically in patients with RA. The most common causes of discontinuation were ineffectiveness and adverse effects.

CONCLUSIONS: The growing market of biologic products necessitates more large-scale studies examining the real-world treatment patterns of these therapy options to provide reassurance to and build trust among patients and clinicians. Our findings suggest the inconclusiveness of current literature on the real-world implications of IFX biosimilars discontinuation and product switching. This review captures the heterogeneity in reported data and identifies areas for future research to provide clarity to the value of IFX biosimilars.

Plain language summary

Biosimilars are biologic medicines that work the same as the original product. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis might be treated with a biosimilar or other biologic. They cost less but work just as well. There is not much information on their use in real life. We summarized what happens when patients switch between products. There are not many studies on biosimilar use in the United States. Future studies will help doctors and patients understand their value.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

As the biosimilars market continues to expand, there is an increasing need for real-world evidence to evaluate their utilization landscape. This study describes literature coverage on the postmarketing switching and discontinuation trends of infliximab biosimilars in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Our findings generated preliminary insights that may inform the direction of future comparative analyses and facilitate the use of biological therapies. Biosimilar uptake may reduce the health care cost burden and improve patient access to biologics.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a debilitating autoimmune disease that is prevalent among approximately 1.3 million people in the United States.1,2 It is the most common type of inflammatory arthritis and is associated with progressive joint damage, functional decline, and long-term adverse health outcomes.1 The initiation process of RA remains elusive, but the disease is a result of abnormal cellular and humoral immune responses.3 The endogenous activity of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α has been correlated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines and enzymatic degradation of joint cartilage.3 When inadequately controlled, RA can result in a wide spectrum of complications, reduced quality of life, and premature mortality.1

The involvement of TNF-α in the pathophysiology of several immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including RA and Crohn’s disease, has led to the development of TNF inhibitors (TNFis).4 TNFis belong to a class of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs known as DMARDs. DMARDs traditionally refer to conventional synthetic DMARDs, such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine. With the availability of new therapeutic agents, the categories of DMARDs have expanded to also comprise biologic DMARDs ([bDMARDs] eg, abatacept, rituximab) and targeted synthetic DMARDs (eg, tofacitinib).5 The adoption of a treat-to-target approach with an early and aggressive intervention using DMARDs has been shown to slow disease progression and preserve joint functionality.5 In the past decades, these agents have transformed the treatment and management of RA. Infliximab (IFX) is a monoclonal antibody and binds to transmembrane TNF-α with high affinity.4 It has been used in clinical practice since the late 1990s to treat chronic diseases, including RA, and has made a substantial impact on the lives of millions of patients.4 In patients with RA who are refractory to conventional DMARDs, IFX, and other TNFis with or without methotrexate are recommended as therapeutic options for patients with early and established RA.5 IFX is well-tolerated and is effective in improving symptom control and physical functions.6

As new biologic therapies are continually introduced to the US market and previously licensed agents are integrated into routine practice, it has become increasingly important to assess the real-world data on the longitudinal use, safety, and effectiveness of these products and characterize their impact on the clinical treatment landscape. Past clinical trials have provided abundant evidence of the rapid response rate and joint protective effect of IFX in patients with bDMARD-naive RA.7 However, clinical measures of signs and symptoms in the randomized controlled trial (RCT) setting may not be applicable in routine clinical practice, as patients who may have more comorbidities or advanced age are not typically included in such trials. Compared with clinical trials, postmarketing observational studies provide real-life data on IFX’s safety and effectiveness in an unselected and heterogeneous population that is highly representative of the general patient population.8 These studies may also have an extended follow-up period that allows for the identification of rare adverse events and other long-term patient outcomes.9 Surrogate markers, such as drug survival rate and time of persistence, are indirect measures of the overall effectiveness and tolerability of IFX.

bDMARDs are effective in inhibiting the progression of RA but may be limited in use because of their high costs. Biosimilars, as defined by the Public Health Act, are biological products demonstrated to have no clinically meaningful difference from their reference product with respect to safety, purity, and potency.10 Structural complexities and variations in cell culture lines during the manufacturing process may contribute to minor differences in clinically inactive components.11 The 3 currently launched biosimilars of reference IFX (Remicade) in the United States, which were included in our search, are IFX-axxq (Avsola), IFX-dyyb (Inflectra), and IFX-abda (Renflexis). IFX-qbtx (Ixifi) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but is not currently marketed in the United States. With demonstrated similarity in safety and efficacy, biosimilars can be initiated in a biologic-naive patient without additional concerns of safety other than those related to the reference product.11 Biosimilars may also be used in patients who are not biologic-naive, and understanding patterns of use in this population is important. The previous version of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline did not provide recommendations on biosimilars because of limited evidence. In 2021, the ACR updated its statement on biosimilars and now considers biosimilars as equivalents of FDA-approved originator products.5 Studying switching and discontinuation can therefore increase the understanding of variables affecting IFX biosimilar continuation and may be helpful for the assessment of the long-term use of IFX biosimilars.

After patent expiry of the innovator product, biosimilars have the potential to promote price competition. The uptake of biosimilars can improve patient access to biologics with lower prices and offer potential savings in the health care budget for reimbursing other innovative medicines. Following regulatory approvals, postmarketing studies on biosimilars are not mandated in the United States, and little real-world data are available to characterize the switching frequencies between the IFX reference product and its biosimilars and whether differences in treatment patterns exist.10,12 Although past clinical trials have shown equivalent efficacy and no greater immunogenicity between IFX and its biosimilars in a short-term setting, clinicians’ hesitancy toward prescribing biosimilar products underlines the need for real-world research to provide reassurance to and build trust among patients and clinicians.10

The Biologics and Biosimilars Collective Intelligence Consortium (BBCIC) is a nonprofit public service initiative that is committed to conducting descriptive utilization analysis and generating real-world evidence on the comparative safety and effectiveness of biologics and biosimilars. The objective of this scoping review is to (1) describe the switching and discontinuation outcomes of IFX biosimilars for the treatment of RA and (2) summarize research methods (eg, study design, data source) of included observational studies. By describing the current clinical landscape on the IFX biosimilars in patients with RA, this study will inform future large-scale observational and comparative effectiveness research of IFX products.

Methods

The search was conducted in 3 databases (ie, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science). Search terms used to identify relevant noninterventional studies included cohort analysis, comparative effectiveness, comparative study, cross-sectional study, drug surveillance program, evidence-based medicine, longitudinal study, medical record review, multicenter study, observational study, prospective study, retrospective study, real-world evidence, and real-world data (Supplementary Table 1, available in online article). The search strategy used MeSH terms for PubMed and Emtree terms for Embase. Inclusion criteria included observational studies published between 2015 and 2020 examining switching and/or discontinuation outcomes of IFX biosimilar products in adult patients with RA. This time range was selected to capture the period after the publication of the 2015 ACR Guideline.5 We excluded studies not published in English, studies not conducted in humans, RCTs, cost/economic analyses unless cost was a subanalysis of a relevant study, biomarker/antibody studies, off-label indications, and case series/reports. Search strategies were refined to comprehensively capture evidence derived from real-world data.

Search results were imported into SciWheel (SAGE Publications Ltd.) for the removal of duplicates and for the initial title and abstract screening. The remaining articles were exported into an Excel spreadsheet for full-text review, data extraction, and further appraisal. Extracted data elements included author, publication year, country of origin, data source, study design, sample size, baseline methotrexate use (if applicable), drug comparators, reasons for switching and discontinuation, and rates of switching and discontinuation. Study periods include the data collection period until the last month of follow-up (if stated).

The most recent literature search was executed on February 18, 2021. This review was structured using the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist, an extension of the original PRISMA statement for systematic reviews that was modified for scoping reviews.13 Literature search, screening, review, and data charting were conducted by a primary reviewer. Quality assurance was performed by 2 additional reviewers.

Results

ARTICLE SEARCH AND SCREENING

Our initial search yielded 886 articles after duplicate removal. Following the title and abstract screening performed by a primary reviewer, 107 articles were selected for full-text assessment, with the addition of 3 articles from manual reference screening (Figure 1). A total of 18 studies were included in this review. Table 1 describes the general characteristics of the studies included in this analysis.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Displaying the Process of Article Identification, Screening, and Selection

TABLE 1.

Summary of Study Characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%), n = 18 |

|---|---|

| Geographical region | |

| Europe | 11 (61.1) |

| Asia | 3 (16.7) |

| North America | 2 (11.1) |

| Othera | 2 (11.1) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2015-2016 | 2 (11.1) |

| 2017-2018 | 9 (50.0) |

| 2019-2020 | 7 (38.9) |

| Study design | |

| Retrospective | 11 (61.1) |

| Prospective | 8 (44.4) |

| Emulating RCT | 1 (5.6) |

| Pragmatic study | 1 (5.6) |

| Data source | |

| Registry | 5 (27.8) |

| Medical record | 6 (33.3) |

| Claims | 4 (22.2) |

| Otherb | 8 (44.4) |

Percentages may not add to 100% in all categories because studies could report multiple designs or data sources used.

a Turkey is a transcontinental country in both Asia and Europe and was categorized as “other.”

b Other data sources include questionnaire platform, medication prescription system, laboratory system, patient-reported outcomes, and other clinical data.

RCT = randomized controlled trial.

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS

Table 2 lists 18 identified studies that reported switching and/or discontinuation for IFX biosimilars. Overall, 13 countries were represented, with most studies conducted in Europe and one study in the United States. Both prospective (n = 8, 44%) and retrospective (n = 11, 61%) studies were included in this analysis. Data source varied across studies, including but not limited to medical records (n = 6; 33%), clinical data (n = 6; 33%), and registries (n = 5; 28%); 4 studies (22%) used administrative claims. Half of the studies reported outcomes that did not differentiate between disease diagnoses (eg, RA, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease), with 3 (17%) describing results only for RA. The number of RA patients using an IFX biosimilar product also varied considerably ranging from 2 to 536, with more than one-third of the studies having a sample size of fewer than 50 patients with RA.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of 18 Biosimilar Studies in the Real-World Setting

| Author, year | Country | Study design | Study center | Data source | Study period a | Biosimilar sample size | Outcomes (DC/SW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avouac et al,201818 | France | Prospective | Single hospital | Medical records | October 2015 to July 2016 (subgroup: up to December 2016 for RP reinitiators) | RA = 31 AxSpA = 131 Crohn’s = 41 UC = 23 Other rheumatic diseases (PsA, juvenile arthritis, undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis) = 20 |

DC, SW |

| Bansback et al,202026 | United States | Retrospective | Multicenter | Registry | January 2017 to September 2018 | RA = 536 PsA = 177 AS = 51 |

DC, SW |

| Boone et al,201817 | Netherlands | Retrospective, pragmatic study | Single center | Medical records, other | July 2016 to April 2017 | Crohn’s = 73 UC = 28 RA = 9 PsA = 5b AS = 10b |

DC |

| Codreanu et al,201833 | Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Romania | Prospective | Multicenter | Clinical data | December 2014 to October 2016 (enrollment period) | RA = 81 AS = 70 |

DC |

| Fisher et al,202034 | Canada | Retrospective (historical cohort), prospective (policy cohort) | Multicenter | Claims | November 2015 to August 2019 (covering 4 cohorts) | Combined (RA, AS, PsA, unknown) = 75 | SW |

| Glintborg et al,201727 | Denmark | Prospective data collection | Multicenter | Registries, other (records from 2 hospitals) | 2000 to September 2016 | RA = 403 PsA = 120 AxSpA = 279 |

DC, SW |

| Grøn et al,201928 | Denmark | Prospective data; emulating RCT using ITT analysis | Multicenter | Registries | January 2013 to January 2018 (covering 3 calendar periods) | RA: cohort 2 = 7 cohort 3 = 225 |

DC |

| Kim et al,201635 | South Korea | Retrospective | Single database covering all populations (multicenter) | Medical claims | April 2009 to March 2014 | All indications, including RA = 983 | SW |

| Kim et al,202036 | Republic of Korea | Retrospective | Multicenter | Medical records | September 2012 to December 2017 | RA = 154 AS = 337 |

DC, SW |

| Layegh et al,201937 | Netherlands | Retrospective | Single center | Medical records, other | September 2015 to January 2018 | RA = 41 PsA = 4 |

DC, SW |

| Nikiphorou et al,201538 | Finland | Prospective | Single hospital | Clinical data, pro | NR | RA = 15 AS = 14 PsA = 7 JIA = 2 chronic reactive arthritis = 1 |

DC, SW |

| Nikiphorou et al,201939 | Finland | Retrospective | Single center | Clinical data, pro | NR (2008 onwards) | RA = 18 AS/SpA = 31 PsA = 21 adult JIA = 4 IBD/REA = 6 Other = 19 |

DC, SW |

| Sung et al,201716 | South Korea | Retrospective | Multicenter | Registry, medical records | October 2011 to September 2015 (enrollment period) | RA = 55 | DC |

| Tweehuysen et al,201840 | Netherlands | Prospective | Multicenter | Medical records, clinical data | July 2015 to May 2016 | RA = 75 PsA = 50 AS = 67 |

DC, SW |

| Valido et al,201941 | Portugal | Prospective | Single center | Registry (clinical data) | November 2015 to November 2017 | RA = 16 PsA = 8 SpA = 36 |

DC, SW |

| Vergara-Dangond et al,201742 | Spain | Retrospective | Single center | Clinical data | June 2015 to January 2016 (SW period) | RA = 2 PsA = 2 AS = 3 |

DC |

| Yazici et al,201815 | Turkey | Retrospective | Multicenter | Claims | December 2010 to June 2016 (enrollment period) | RA = 92 | DC, SW |

| Yazici et al,201814 | Turkey | Retrospective | Multicenter | Claims | October 2014 to May 2015 (enrollment period) | RA = 204 IBD = 77 |

DC, SW |

a Study periods are not specific to IFX biosimilars.

b We noted discrepancy in sample size for PsA and AS and reported data based on table results.

AS = ankylosing spondylitis; AxSpA = axial spondyloarthritis; biosim = biosimilar; Crohn’s = Crohn’s disease; DC = discontinuation; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; ITT = intention-to-treat; JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; NR = not reported; PsA = psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis; PRO = patient-reported outcome; RCT = randomized controlled trial; REA = reactive arthritis; RP = reference product; SpA = spondyloarthritis; SW = switching; UC = ulcerative colitis.

DISCONTINUATION RATES AND CAUSES

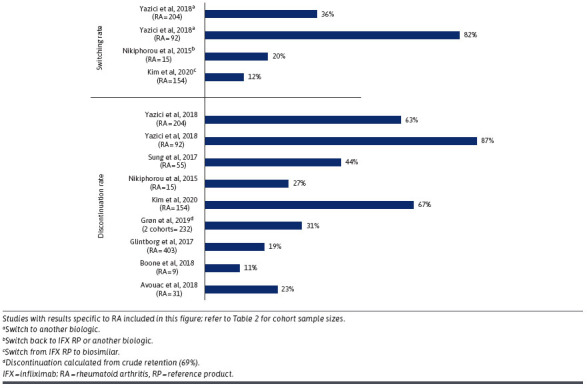

Overall, 16 studies reported outcomes related to the discontinuation of IFX biosimilars with discontinuation rates varying considerably, ranging from 8.3% to 87.0%, as reported by one study of patients who had switched from IFX reference product to an IFX biosimilar and subsequently discontinued the biosimilar (Table 3).14 Of these studies, 9 articles had discontinuation rates (11% to 87%) specific to the RA sample (Figure 2). Seven studies defined or alluded to “discontinuation” with great variations in their definitions, for example, cessation of IFX administration for more than 90 days, evidence of a switch to another biologic or absence of a claim for more than 120 days, and date of the first missed dose as recorded by the physician (Supplementary Table 2). Four studies directly compared discontinuation rates between the IFX reference product and biosimilars; 3 of them reported outcomes specific to patients with RA (N = 351). Among these 3 studies, discontinuation rates for the IFX reference product ranged from 33.9% to 46.7% and from 43.6% to 87.0% for IFX biosimilars. Two articles that evaluated statistical significance found higher discontinuation rates in patients who switched to CT-P13 (named IFX-dyyb after FDA approval).14,15 However, Sung et al compared retention rates over a 2-year period and reported no difference.16 In this 2017 multicenter study conducted in South Korea, patients with RA who were initiated on IFX reference or CT-P13 were included regardless of prior history of bDMARD use. The discontinuation rate was higher in the IFX reference group than in the CT-P13 group both before 6 months before (35.6% vs 23.6%) and during the mean observation period (46.7% over 16.7 ± 15.3 months for the reference product; 43.6% over 11.8 ± 7.7 months for CT-P13). However, when directly comparing the retention rates over 2 years, no difference was noted (52.6% vs 36.9%; P = 0.98).

TABLE 3.

Discontinuation and Switching Outcomes of IFX Biosimilars

| Author, year | DC or retention rate a | DC causes a | Switch rate a | Reasons for Switch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avouac, J 201818 | DC rate: overall (23%), RA (23%), AxSpA (27%), other rheumatic diseases (25%), Crohn’s (22%) | All indications: ineffectiveness (80%), AEs (8%), lost to follow-up (10%), pregnancy (2%) | All indications: Restart RP (79.7%) TNFi switch (8.5%) Switch to new MOA (3.4%) Biologic-free (8.5%) Mean time to switch, RP to biosimilar: overall 5.8 ± 4.9 years, RA 7.4 ± 5.5 years |

Setting: voluntary systematic switch to biosimilar |

| Bansback, N 202026 | All indications: Crude persistence: IFX-dyyb (80%), RP (75%); P = 0.02 Adjusted HR for persistence: 0.83 (vs RP); P = 0.07 |

All indications: 57.4% of biosimilar users had switched from RP | ||

| Boone, NW 201817 | Biosimilar discontinuation: RA (11%), AS (20%), IBD (7%) | RA (n = 1): ineffectiveness due to nocebo effect | Setting: nonmedical switch to biosimilar | |

| Codreanu, C 201833 | All indications: 13.2% discontinued biosimilar (CT-P13) | All indications: AEs (35%), ineffectiveness (25%), nonadherence (10%), patient request (10%), sponsor request (5%), lost to follow-up (15%) | ||

| Fisher, A 202034 | All indications: Policy cohort: 20.5% switch from RP to biosimilar Historical cohort: <5% switch from RP to another biologic |

Introduction of the British Columbia Ministry of Health Biosimilars Initiative (2019) | ||

| Glintborg, B 201727 | Overall 16% discontinued IFX biosimilar: RA (18.9%); PsA (13.3%); AxSpA (14.3%) All indications: HR for DC (vs RP): 1.31 [1.02-1.68]; P = 0.03 |

All indications: ineffectiveness (53.8%), AEs (28.0%), remission (3.8%), cancer (3.8%), death (1.5%), several reasons (2.3%), other reasons (eg, pregnancy, surgery; 6.1%), unknown (0.8%) | Time to switch, RA: 7.3 ± 3.6 years | Nationwide nonmedical switch to biosimilar (CT-P13) |

| Grøn, KL 201928 | RA-specific: Adjusted HR for discontinuation, 0-90 days (vs CZP): IFX biosimilar 0.58 [0.33-1.10] 91-365 days (vs CZP): IFX biosimilar 0.83 [0.59-1.17] Crude retention: IFX biosimilar (69%), CZP (60%), ABA (57%) Biosimilar: CT-P13 |

RA-specific:DC causes: Ineffectiveness (36-60%), AEs (15%-42%), otherb (<10%) | ||

| Kim, SC 201635 | All indications: 41% of biosimilar users switched from RP; proportion of biosimilar IFX increased by 19% from November 2012 to March 2014 |

|||

| Kim, TH 202036 | Overall 48.7% RA: overall 66.9%, naive 68.1%, switched 57.9% AS: overall 40.4%, naive 38.4%, switched 44.1% |

Overall ineffectiveness (40.6%), AEs (10.5%), loss to follow-up (14.6%), pregnancy (3.4%), drug holiday (14.6%), other (16.3%) RA overall: ineffectiveness (51.5%), AEs (11.7%), lost to follow-up (8.7%), pregnancy (3.9%), drug holiday (15.5%), other (8.7%) AS overall: ineffectiveness (32.4%), AEs (9.6%), loss to follow-up (19.1%), pregnancy (2.9%), drug holiday (14.0%), otherc (22.1%) |

12.3% (RA) and 35.0% (AS) switched from RP to biosimilar | Included patients who underwent nonmedical switch (CT-P13) and those who were biosimilar-naive |

| Layegh, Z 201937 | Overall Remsima DC: 13% | All indications: At 2-year follow-up: 1 patient on Remsima stopped because of AE (lung malignancy) After 2-year follow-up: 1 stopped because of AE (skin cancer) |

All indications: Overall switch rate (Remsima to another TNFi): 4% At 2-year follow-up: 2 patients receiving Remsima switched, both because of inefficacy; 3 patients switched back to RP After 2-year follow-up: 1 continued receiving RP; 1 switched to ABA because of ineffectiveness |

Setting: voluntary switch from Remicade to Remsima |

| Nikiphorou, E 201538 | DC rate: overall (28.2%), RA (26.7%), AS (21.4%), PsA (42.9%), JIA (50.0%), chronic reactive arthritis (0%) Biosimilar: CT-P13 |

RA-specific (n = 4): AE (antidrug antibodies) (75%), subjective reasons with no objective disease deterioration (25%) |

Switch rate, RA: 20% (n = 3) Among 3 patients who switched: 1 restarted RP, 1 switched to GLM, and 1 switched to RTX Mean time to switch, RA: 6.5 years |

|

| Nikiphorou, E 201939 | All indications: DC rate: RP (62%), biosimilar (30%) Biosimilar: CT-P13 |

All indications: DC reasons for new initiators, RP vs biosimilar: ineffectiveness (18.0% vs 5.0%), SE (9.1% vs 5.0%), antibodies (2.0% vs 5.0%), comorbidity (1.7% vs 1.0%), switch (to biosimilar per local policy or other: 24.0% vs 10.0%), remission (2.0% vs 1.0%), pregnancy (1.0% vs 1.0%), unknown (4.1% vs 2.0%) DC reasons for RP to biosimilar switchers: ineffectiveness (3.2%), SE (5.4%), antibodies (2.1%), comorbidity (1.1%), switch 6.5%, pregnancy (1.1%), unknown (4.3%) |

All indications: Switch rate: RP (24%) vs biosimilar 10%) |

|

| Sung, YK 201716 | RA-specific: DC rate (of entire observation period): RP (46.7%) vs biosimilar (43.6%) DC rate (before 6 months): overall (29%), RP (35.6%) vs biosimilar (23.6%) |

AEs: RP (37.5%), biosimilar (19.0%)Ineffectiveness was the most common reason in both groups but was only reported with RP | ||

| Tweehuysen, L 201840 | All indications: 24% discontinued biosimilar |

All indications: ineffectiveness (55%), AEs (23%), combination (21%) | Among 47 pooled patients who stopped CT-P13: 79% restarted RP, 15% switched to another biologic, and 6% did not use a biologic | Setting: voluntary open-label transition from RP to biosimilar (CT-P13) |

| Valido, A 201941 | All indications: After SW: 8.3% stopped therapy |

All indications: disease progression (5%), AEs (1.7%), lost to follow-up (1.7%) | Mean time to switch to biosimilar (range), RA: 8.0 (4.8-16.6) years Among 5 patients who stopped biosimilar, 1 patient restarted RP, 3 switched to new MOA, and 1 was lost to follow-up |

Setting: nonmedical switch from RP to biosimilar (CT-P13) (n = 60) |

| Vergara-Dangond, C 201742 | All indications: DC rate: 1 patient stopped because of AE (14.3%) |

1 patient stopped because of AE (14.3%) | Setting: 7 of 13 patients were switched to an IFX biosimilar (CT-P13) | |

| Yazici, Y 201815 | RA-specific: DC rated: 33.9% (RP continuers) vs 87.0% (RP to biosimilar switchers); P < 0.001 Mean time to discontinuation: 276 days (RP continuers) vs 132 days (RP to biosimilar switchers); P < 0.001 Biosimilar: CT-P13 |

RA-specific: Switch to another biologic during follow-up: 19.0% (RP continuers) vs 81.5% (RP to biosimilar switchers); P < 0.001 Among RP continuers who switched: 77.4% switched to another TNFi, 23.6% switched to a new MOA Among RP to biosimilar switchers: 88% restarted RP, 12% switched to another TNFi |

||

| Yazici, Y 201814 | RA: DC rate: 42.1% (RP); 62.8% (biosimilar); P < 0.001 Time to switch: 263 days (RP) vs 207 days (biosimilar); P < 0.001 IBD: DC rate: 37.5% (RP); 62.3% (biosimilar); P < 0.001 Time to switch: 288 days (RP) vs 177 days (biosimilar); P < 0.001 Biosimilar: CT-P13 |

RA: Switch to another biologic: 23.5% (RP) vs 35.8% (biosimilar); P < 0.001 In the RP initiator cohort, patients switched to IFX biosimilar (34.8%) or other biologics (65.2%) In the biosimilar cohort, patients switched to RP (56.2%) or other biologics (43.8%) IBD: Switch to another biologic: 14.1% (RP) vs 50.6% (biosimilar); P < 0.001 RP initiators switched to biosimilar (46.5%) or other biologics (53.5%) The biosimilar cohort switched to RP (82.1%) or other biologics (17.9%) |

a Reported by author or data allowed for calculation.

b Cancer, plan for pregnancy, treated at another hospital, infection, lost to follow-up, death, surgery, project participation, remission, other, or unavailable.

c Change in therapy to IFX or other bDMARD, patient decision, investigator judgment, surgery, patient switched to another clinical study, improvement in symptoms, insurance criteria not fulfilled, trial ended.

d We noted discrepancy in discontinuation rate for switchers and reported data based on the Results section.

Ab = antibody; ABA = abatacept; AE = adverse effect; AS = ankylosing spondylitis; AxSpA = axial spondyloarthritis; Crohn’s = Crohn’s disease; CT-P13 = IFX biosimilar; CZP = certolizumab pegol; DC = discontinuation; ETN = etanercept; GLM = golimumab; HR = hazard ratio; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MOA = mechanism of action; PsA = psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis; RP = IFX reference product; RTX = rituximab; SE = side effect; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

FIGURE 2.

IFX Biosimilar Switching and Discontinuation Rates in Patients With RA

A total of 13 studies (72%) reported reasons for discontinuation (Table 3). The most common causes of discontinuation were ineffectiveness reported by 10 studies (56%) and adverse effects reported by 12 studies (67%). Five of these studies (28%) reported discontinuation reasons specific to patients with RA, with ineffectiveness being the most common cause in 4 articles. Among all reasons for discontinuation in patients with RA, the proportion of discontinuation due to ineffectiveness ranged from 36% to 100%, and discontinuation due to adverse effects ranged from 12% to 75%. Other less common causes include disease remission, loss to follow-up, patient preference, sponsor request, pregnancy, drug holiday, insurance policy, comorbidities and mortality, and other unknown causes.

SWITCHING RATES AND PATTERNS

Twelve articles (67%) reported switching rates; 4 of them described switching rates in patients with RA instead of a pooled population (Table 3). The switching rates reported by these 4 studies varied significantly from 12.3% to 81.5% depending on the type and direction of switch (eg, from biosimilar to IFX reference product or another biologic) (Table 3; Figure 2). There was a lot of variety with respect to the studied indications, type of switching, and method of switching (ie, policy-mandated process as opposed to voluntary transition). According to Kim et al and Nikiphorou et al, 12% and 20% of patients switched from IFX originator to biosimilar.34,36 In 2 studies by Yazici et al, biosimilar users restarted on or switched to an IFX reference product (88%, 56%) or switched to another biologic product (12%, 43.8%).14,15

In one study by Boone et al, the authors discussed the perceived nocebo effect as a cause of medication switching in nonmedical biosimilar transitions.17 Among 9 patients with RA, 1 patient (11%) stopped receiving IFX biosimilar after the first infusion, attributed to “perceived diminished effect and new-onset headache.” The patient was then reinitiated back on the IFX reference product. In a systematic voluntary switch, Avouac et al reported the switching patterns in the pooled patient sample (n = 59) that stopped IFX biosimilars: 79.7% restarted the IFX reference, 8.5% switched to another TNFi, 3.4% switched to a different class, and 8.5% remained biologic-free.18

Discussion

The biosimilar approval process is highly regulated by the FDA, European Medicines Agency, and the World Health Organization, and biosimilars must be proven to have no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and safety to receive market approval. However, many patients and health care providers have unresolved concerns around the manufacturing process of these products and their equivalency in therapeutic effects to the originator.19 Observational studies provide real-world data on safety and effectiveness in an unselected, heterogeneous population with few to no exclusion criteria, rendering the patient sample to be highly representative of the general patient population.8 Other reviews have been published recently describing biosimilar switching, including biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching.20 However, the scope of our study included IFX biosimilar switching and discontinuation only in patients with RA. We chose to conduct a scoping review rather than a systematic review as we sought to assess methods and approaches to observational research, along with describing switching and discontinuation patterns, rather than to quantify a specific treatment effect.21

This scoping review provides a summary of outcomes related to the switching and/or discontinuation of IFX biosimilars in observational studies and captures the heterogeneity in reported outcomes and the types of research design and data source used to conduct these real-world studies. Data on switching and discontinuation are reflective of factors associated with IFX persistence and are conducive to the assessment of long-term IFX biosimilar use. Discontinuation rates in the real-world setting have been found to exceed the “expected” levels (10%) reported for CT-P13 in the phase 4 randomized, double-blinded NOR-SWITCH study and for the IFX reference as long-term maintenance therapy.22-25 Bakalos et al used this literature threshold as a reference in their systematic review of real-world observational studies.19 Our findings were consistent with this statement in that we observed a range of data with significant deviation from this threshold of 10% (8.3%-87.0%). Among 5 studies with lower discontinuation rates (ie, 8.3%, 11%, 13%, 13%, 14%), 4 studies had a pooled sample with several inflammatory conditions. This suggests RA itself may be associated with higher medication withdrawal rates. Likewise, among the included studies, discontinuation rates for the IFX reference product were also past this reference value (33.9%-62%).

Two articles that directly compared discontinuation rates between IFX originator and biosimilar found significantly higher withdrawal rates in the biosimilar cohort.14,15 When we looked at studies with direct comparison of retention rates, however, 2 out of 3 found no statistically significant difference.16,26,27 In the Danish nationwide nonmedical switch study from IFX reference to CT-P13 by Glintborg et al, the 1-year retention rates were directly compared between IFX reference (control) and CT-P13 users and were not statistically different (86.2 vs 84.1%; P = 0.22).27 This is consistent with the findings by Sung et al, although they reported considerably lower rates of discontinuation (IFX biosimilar 52.6% vs reference 36.9%, P = 0.98) over a longer period of follow-up for more than 2 years.16 Amongst CT-P13 users in the study by Glintborg et al, it was observed that the duration of prior IFX reference use may have had an impact on retention rates, as those previously receiving IFX reference for 5 years or less had lower persistence compared with those receiving IFX for more than 5 years (78% vs 87%; P = 0.001).27 One study by Bansback et al identified a difference in crude persistence between IFX reference (75%) and IFX-dyyb (CT-P13; 80%; P = 0.02).26 It is unclear whether the statistical significance will remain once the outcome is adjusted by confounding variables.

We also identified studies with interesting and novel designs. For instance, Grøn et al conducted a comparative observational cohort study emulating an RCT in which a different biologic product was mandated to be taken with methotrexate each year per the national Danish guideline.28 Previously, it has been shown that observational studies may produce similar results when adopting a design emulating RCTs.29 The Danish formulary was then used as a randomization tool to reduce confounding because the drug of choice was solely dictated by the calendar year and not patient-related factors.

Current evidence remains inconclusive about the real-world implications of IFX switching. We recommend future research to focus on investigating safety and effectiveness endpoints in patients switching to and from IFX biosimilars. We did not identify any articles reporting switching between IFX biosimilar products at the time of this review, but we anticipate future studies will begin to address this switch in a US context. Ideally, patients should be included in the decision to switch based on discussion with their provider through shared decision-making. When this is impractical in certain circumstances, real-world data elucidating whether there is a clinical effect in such transitions will provide clarity and ease to the minds of patients, their caregivers, and health care professionals recommending this practice.

LIMITATIONS

Although we summarized findings across studies with different methodology (eg, data source) and reimbursement structures (ie, policy by country), we also considered the potential presence of confounding factors that may complicate the interpretation of our findings. For instance, methotrexate is recommended to be used concurrently with IFX for improved tolerability, and variations in adherence to this recommendation may lead to differences in treatment persistence. It has been found that this combination therapy is associated with improved symptoms of inflammation, physical function, and patient’s quality of life and offers great clinical benefit in preventing the progression of joint damage.30 Additionally, the flexibility in IFX dosing may also impact treatment response and tolerability as maintenance therapy can be dosed up to 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks. We did not specifically collect data on dosing regimens in this review; nonetheless, standardizing methotrexate use and IFX dosing in treatment protocols may improve comparison across studies. Product naming varied across countries and, in some cases, was not specified in the text, so it was not always possible to differentiate which biosimilar was included in the study. However, using regulatory approval dates or product launch dates when available, it would be possible to estimate which product was likely included. In Table 3, each biosimilar is referred to according to how it was stated in the study. We only included studies published through 2020 in this analysis, and although that provides an initial assessment of IFX treatment patterns, we recommend repeating this study with more recent studies as more biosimilars become available.

We identified 4 articles that collected claims data, which include information like diagnostic codes and filled prescriptions. It should be noted that there is an inherent risk of misclassification with claims data that may impact the quality of collected data.31 Additionally, claims data are restricted in providing insights into some clinical outcomes of RA, such as disease remission and disease activity assessed by measures such as the Disease Activity Score 28 joints, Clinical Disease Activity Index, or Simple Disease Activity Index.32 However, compared with medical records and registries that may provide more comprehensive clinical detail, claims allow for longitudinal assessment of health care utilization at the patient, group, or population level and may be used to investigate associations between interventions and outcomes.9 Compared with RCTs, claims studies have access to a larger established patient population and an extended follow-up period, which allows for the identification of rare adverse events and long-term patient outcomes and forms the basis of our design of a future broad-scale comparative safety and effectiveness study.9

We conducted this scoping review to map out the evidence around switching and discontinuation of IFX biosimilars in the existing literature body. It is a precursor study to future comparative effectiveness research. In summary, we found that many articles reported a small sample size, which may not represent the overall patient population and limits the interpretation of results. In addition to having a sufficient sample, we recommend future research to differentiate outcomes by disease state to minimize confounding effects and provide clarity to the utilization pattern of IFX biosimilars in RA. Furthermore, we highlight the value of claims databases and the importance of evaluating longitudinal real-world data when assessing switching and discontinuation outcomes.

Conclusions

Because new biological products are continually introduced to the US market and integrated into clinical practice, it has become increasingly important to characterize the postmarketing utilization of these products and the current treatment landscape to optimize patient care. This project is an important preliminary study towards a large-scale comparative research study examining the safety and effectiveness of IFX products in the US health care setting. It may also offer real-world evidence on the implementation and treatment trends of IFX and has the potential to inform clinicians, payers, and policymakers of the direction of future research and facilitate more utilization of biological therapies. Encouraging the uptake of IFX biosimilar products that are demonstrated to be similar in safety and efficacy may reduce the cost burden on the health care system and allow patients access to optimal care to improve health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the BBCIC, a nonprofit, multistakeholder collaborative. The work herein is that of the BBCIC consortium and does not reflect the views of any individual participant organization and the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the BBCIC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/rheumatoid-arthritis.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter TM, Boytsov NN, Zhang X, Schroeder K, Michaud K, Araujo AB. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004-2014. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:1551-7. doi:10.1007/s00296-017-3726-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scherer HU, Haupl T, Burmester GR. The etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2020;110:102400. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melsheimer R, Geldhof A, Apaolaza I, Schaible T. Remicade (infliximab): 20 years of contributions to science and medicine. Biologics. 2019;13:139-78. doi:10.2147/BTT.S207246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:1108-23. doi:10.1002/art.41752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults and an economic evaluation of their cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(42):iii-229. doi:10.3310/hta10420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung YK, Jung SY, Kim H, et al. Factors for starting biosimilar TNF inhibitors in patients with rheumatic diseases in the real world. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227960. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen AT, Goto S, Schreiber K, Torp-Pedersen C. Why do we need observational studies of everyday patients in the real-life setting?: Table 1. European Heart Journal Supplements. 2015;17:D2-D8. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suv035 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camm AJ, Fox KAA. Strengths and weaknesses of ‘real-world’ studies involving non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Open Heart. 2018;5:e000788. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2018-000788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingrasciotta Y, Cutroneo PM, Marciano I, Giezen T, Atzeni F, Trifiro G. Safety of biologics, including biosimilars: Perspectives on current status and future direction. Drug Saf. 2018;41:1013-22. doi:10.1007/s40264-018-0684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kos IA, Azevedo VF, Neto DE, Kowalski SC. The biosimilars journey: Current status and ongoing challenges. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212543. doi:10.7573/dic.212543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi S, Ghang B, Jeong S, et al. Association of first, second, and third-line bDMARDs and tsDMARD with drug survival among seropositive rheumatoid arthritis patients: Cohort study in a real world setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:685-91. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467-73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. A descriptive analysis of real-world treatment patterns of innovator (Remicade) and biosimilar infliximab in an infliximab-naive Turkish population. Biologics. 2018;12:97-106. doi:10.2147/BTT.S172241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. Analysis of real-world treatment patterns in a matched rheumatology population that continued innovator infliximab therapy or switched to biosimilar infliximab. Biologics. 2018;12:127-34. doi:10.2147/BTT.S172337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung YK, Cho SK, Kim D, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis patients who started biosimilar infliximab. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:1007-14. doi:10.1007/s00296-017-3663-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:655-61. doi:10.1007/s00228-018-2418-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avouac J, Molto A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: The experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47:741-8. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakalos G, Zintzaras E. Drug discontinuation in studies including a switch from an originator to a biosimilar monoclonal antibody: A systematic literature review. Clin Ther. 2019;41:155-73 e13. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen HP, Hachaichi S, Bodenmueller W, Kvien TK, Danese S, Blauvelt A. Switching from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic: A systematic review of studies. BioDrugs. 2022;36:625-37. doi:10.1007/s40259-022-00546-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, et al. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: Results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:22-32. doi:10.1002/art.27227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): A 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304-16. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neovius M, Arkema EV, Olsson H, et al. Drug survival on TNF inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis comparison of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:354-60. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a single-centre cohort. Gut. 2009;58:492-500. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.155812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bansback N, Curtis JR, Huang J, et al. Patterns of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) biosimilar use across United States rheumatology practices. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:79-83. doi:10.1002/acr2.11106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glintborg B, Sorensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1426-31. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gron KL, Glintborg B, Norgaard M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of certolizumab pegol, abatacept, and biosimilar infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated in routine care: Observational data from the Danish DANBIO registry emulating a randomized trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1997-2004. doi:10.1002/art.41031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernan MA, Alonso A, Logan R, et al. Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: An application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2008;19:766-79. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181875e61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-tumor necrosis factor trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy study group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1594-602. doi:10.1056/NEJM200011303432202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konrad R, Zhang W, Bjarndottir M, Proano R. Key considerations when using health insurance claims data in advanced data analyses: An experience report. Health Syst (Basingstoke). 2019;9:317-25. doi:10.1080/20476965.2019.1581433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandran U, Reps J, Stang PE, Ryan PB. Inferring disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis using predictive modeling in administrative claims databases. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Codreanu C, Sirova K, Jarosova K, Batalov A. Assessment of effectiveness and safety of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) in a real-life setting for treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34:1763-9. doi:10.1080/03007995.2018.1441144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher A, Kim JD, Dormuth CR. Rapid monitoring of health services utilization following a shift in coverage from brand name to biosimilar drugs in British Columbia-An interim report. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29:803-10. doi:10.1002/pds.5008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SC, Choi NK, Lee J, et al. Brief report: Utilization of the first biosimilar infliximab since its approval in South Korea. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1076-9. doi:10.1002/art.39546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim TH, Lee SS, Park W, et al. A 5-year retrospective analysis of drug survival, safety, and effectiveness of the infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40:541-53. doi:10.1007/s40261-020-00907-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Layegh Z, Ruwaard J, Hebing RCF, et al. Efficacious transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in clinical practice. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:869-73. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.13512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikiphorou E, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (Infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1677-83. doi:10.1517/14712598.2015.1103733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikiphorou E, Hannonen P, Asikainen J, et al. Survival and safety of infliximab bio-original and infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) in usual rheumatology care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37:55-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:60-8. doi:10.1002/art.40324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valido A, Silva-Dinis J, Saavedra MJ, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and cost analysis of a systematic switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 of all patients with inflammatory arthritis from a single center. Acta Reumatol Port. 2019;44:303-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vergara-Dangond C, Saez Bello M, Climente Marti M, Llopis Salvia P, Alegre-Sancho JJ. Effectiveness and safety of switching from innovator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: A real-world case study. Drugs R D. 2017;17:481-5. doi:10.1007/s40268-017-0194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]