Abstract

Changes in narcissistic traits (e.g., entitlement) following the ceremonial use of ayahuasca were examined across three timepoints (baseline, post-retreat, 3-month follow-up) in a sample of 314 adults using self- and informant-report (N = 110) measures. Following ceremonial use of ayahuasca, self-reported changes in narcissism were observed (i.e., decreases in Narcissistic Personality Inventory [NPI] Entitlement-Exploitativeness, increases in NPI Leadership Authority, decreases in a proxy measure of narcissistic personality disorder [NPD]). However, effect size changes were small, results were somewhat mixed across convergent measures, and no significant changes were observed by informants. The present study provides modest and qualified support for adaptive change in narcissistic antagonism up to 3 months following ceremony experiences, suggesting some potential for treatment efficacy. However, meaningful changes in narcissism were not observed. More research would be needed to adequately evaluate the relevance of psychedelic-assisted therapy for narcissistic traits, particularly studies examining individuals with higher antagonism and involving antagonism-focused therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: ayahuasca, psychedelics, narcissism

Psychedelic-assisted therapies have recently been shown to be efficacious within randomized control trials in remediating internalizing psychopathology, including life-threatening illness-related anxiety (Griffiths et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016), treatment-resistant and major depression (e.g., Carhart-Harris, Bolstridge, et al., 2016, 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019), and substance use (Bogenschutz et al., 2015, 2022; Johnson et al., 2014). However, although psychedelic therapy is often ascribed a transdiagnostic treatment mechanism, less is known about its utility for addressing alternative areas of psychopathology. Among prospective targets of inquiry, the Antagonistic Externalizing spectrum of psychopathology (e.g., Cluster B personality disorders) is a particularly important candidate, as recent evidence provides support for psychedelic-induced reductions in antagonistic personality (e.g., Carhart-Harris et al., 2016; Weiss, Nygart, et al., 2021; Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021), criminal recidivism (Hendricks et al., 2014), and arrests involving intimate partner violence (Walsh et al., 2016). Antagonistic externalizing is a dimension of externalizing psychopathology contained within the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al., 2017), a data-driven, integrative model of psychopathology. Antagonistic externalizing describes tendencies to “navigate interpersonal situations using antipathy and conflict, and to hurt other people intentionally, with little regard for their rights and feelings” (Krueger et al., 2021, p. 172), and is exemplified by patterns of behavior involving aggression, violence, criminality, and rule-breaking. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of psychedelic compounds in addressing narcissistic personality, considered to be a core example of the spectrum. Narcissism and its diagnostic counterpart, narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), are characterized by grandiosity, attention-seeking, entitlement, callousness, hostility, and a host of negative intra- and interpersonal outcomes, including aggression (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021), distress experienced by close others (Miller et al., 2007), and domineering and intrusive interpersonal behavior (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2009).

The present study represents the first prospective inquiry into the effects of psychedelics on narcissism. We focus on an indigenous psychedelic treatment involving the ceremonial use of ayahuasca, huachuma, and bufo (described in the Methods section). This combination of psychedelic medicines will be referred to hereafter as ayahuasca for simplicity and because the latter two substances were not administered to all participants. As detailed in other work (Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021; Wolff et al., 2019), ceremony can produce profound psychological experiences of awe, clarity, love, and heightened introspective capacity that have been linked to decreases in trait neuroticism. Some of these elements appear to parallel well-studied treatment mechanisms within cognitive-behavioral and acceptance and commitment psychotherapies, including cognitive reappraisal and psychological flexibility (Agin-Liebes et al., 2022), making them intriguing candidates for clinical study. In what follows, we will review our current understanding of narcissism and the unique effects of ayahuasca on narcissism.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF NARCISSISM

Modern conceptualizations of narcissism have departed from a monolithic categorical understanding (e.g., NPD) in favor of a multidimensional conceptualization. At a superordinate level of the hierarchy, researchers have identified two predominant phenotypes of narcissism, within which exist more granular dimensions. Grandiose narcissism is characterized by high self-esteem and traits related to immodesty, interpersonal dominance, self-absorption, and manipulativeness. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism is characterized by internalizing, low self-esteem, psychological distress, feelings of inferiority, egocentricity, distrust, and hostile aggression (Weiss & Miller, 2018). Diagnostic models of narcissism, such as the DSM-5 NPD category and NPD operationalized within the DSM-5 Section III Alternative Model of Personality Disorders (AMPD), characterize narcissism largely by the grandiose phenotype (e.g., Fossati et al., 2005). Given the relevance of grandiose narcissism to clinical models of narcissism and the attention paid to internalizing psychopathology elsewhere, we focus on this component. More differentiated dimensions within grandiose narcissism, namely agentic extraversion and narcissistic antagonism, are also critical to measure (e.g., Trifurcated Model of Narcissism [TMN], Crowe et al., 2019; Krizan & Herlache, 2018). Agentic extraversion is thought to account for the “adaptive” correlates unique to grandiosity (e.g., drive, leadership, self-esteem), whereas antagonism, considered to be narcissism’s maladaptive core, is characterized by manipulativeness, exploitativeness, entitlement, and lack of empathy (Crowe et al., 2019) and coincides with NPD criteria and antagonistic externalizing.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF EMPIRICALLY SUPPORTED TREATMENT FOR NARCISSISTIC PERSONALITY DISORDER

There are substantial societal costs associated with narcissism. NPD/narcissism is more common in forensic samples, and is co-occurring with antisocial personality disorder (Coid, 2003) and psychopathy (Weiss, Sleep, et al., 2021), which likely emanates from a shared core of antagonism across these conditions (Lynam & Miller, 2019; Weiss, Sleep, et al., 2021). Other societal costs include selfishness and abuse in relationships, higher risk of aggression following ego threat, and a competitive decision-making style that contributes disutility to others (Campbell et al., 2004, 2005; Ponti et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, there are few empirically supported options for its treatment. In an empirical review, Dhawan and colleagues (2010) found that no treatment trials have been conducted, despite finding several “low-quality case series, case reports, and anecdotal reports” (p. 337), which they concluded were “highly vulnerable to bias” (p. 337). It is of additional concern that individuals with these traits tend to avoid treatment (Miller et al., 2007), despite some willingness to work toward change in these traits (Sleep et al., 2022). Such a relationship to treatment makes it important to identify available treatments that are well tolerated and time limited. Novel therapies characterized by lower dropout, such as MDMA-assisted therapy (e.g., Feduccia et al., 2019), are considered vital to practically address antagonistic externalizing.

THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FOR PSYCHEDELIC-INDUCED EFFECT ON NARCISSISM

Given the paucity of ideas and resources for addressing maladaptive narcissistic features, it behooves psychological medicine to explore novel treatment avenues. Despite a long history of use in ancient cultures (e.g., Schultes & Hofmann, 1979), serotonergic psychedelic compounds (i.e., 5-HT2A receptor agonists) did not gain wide interest or popularity in Western industrialized nations until the 1960s. More recently, empirical interest in therapeutic applications of psychedelic compounds has increased substantially, and scholars have begun to consider psychedelics for the treatment of personality psychopathology (Zeifman & Wagner, 2020). Direct research on psychedelic-induced changes in narcissism has been limited to retrospective self-report work (van Mulukom et al., 2020). Research with the most meaningful relevance to narcissism involves prospective work examining psychedelic-induced effects on basic personality traits related to narcissism, as specified by recent empirically derived models (i.e., extraversion/agentic extraversion and agreeableness/narcissistic antagonism; Crowe et al., 2019). Several studies have demonstrated adaptive changes for neuroticism (i.e., the tendency to experience negative emotions) and related constructs (e.g., Barbosa et al., 2009; Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021); agreeableness/antagonism (e.g., Carhart-Harris et al., 2016; Netzband et al., 2020), including reductions in a quarrelsome interpersonal style (Weiss, Nygart, et al., 2021); and extraversion, especially in traits related to social functioning (i.e., warmth, friendliness, gregariousness; Erritzoe et al., 2018). Taken together, the current literature base supports inquiring into the use of psychedelics as a potential treatment for maladaptive narcissistic traits.

Theoretically, psychedelic compounds could exert therapeutic effects on narcissistic personality in at least three possible ways: intervening in individuals’ narcissistic self-conception, promoting a communal interpersonal style, and/or enhancing affective empathy. Narcissistic antagonism may respond to treatment through dissolving1 a grandiose self-conception. States of ego dissolution are commonly identified within psychedelic experience (James, 1882; Nour et al., 2016), wherein individuals describe a diminished sense of one’s previous self-conception. Ego dissolution also accompanies a subjective sense of unification with a larger whole, including external unity with objects and entities. The unitive aspect of these experiences and outer attentional focus may be convergent with self-reports of perceived connectedness to oneself, others, surroundings, and nature, some of which have shown evidence of persisting post-acutely (e.g., Forstmann et al., 2020). Enhanced connectedness is intriguing as an additional theoretical mechanism for change in narcissism, as psychedelic use may reduce narcissism by diminishing inward focus on the self while promoting a communal, versus agentic, interpersonal style. In addition, narcissism has been linked to impairment in affective empathy (Ritter et al., 2011; Watson et al., 1984), which is characterized by reduced capacities for empathy and intimacy, as specified by the DSM-5 AMPD. Because acute and post-acute psychedelic-induced increases in affective empathy have been observed in previous work (Dolder et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2019; Pokorny et al., 2017; Uthaug et al., 2021), it is conceivable that psychedelic use can intervene in narcissism through remediating impairment in affective empathy (cf. Weiss, Nygart, et al., 2021).

Alternatively, some scholars suggest that psychedelic experiences may promote narcissistic traits, stating that rarefied experiences of unitive consciousness and positive mood (e.g., oceanic boundlessness) may lead to ego inflation and a sense of spiritual superiority rather than “quieting of the ego” (Kaufman, 2021; Vonk & Visser, 2021). Indeed, this pattern was tentatively observed in a sample of ayahuasca users who showed decreases in the Five-Factor model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1992) personality facet of Modesty, a core feature of grandiose narcissism (Weiss et al., 2019), against a wider trend of enhanced agreeableness (Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021).

THE PRESENT STUDY

The present study examined change in narcissistic traits in relation to the ceremonial use of ayahuasca and other psychedelic compounds in a sample of 314 adults using measures of narcissism and personality across three timepoints (Baseline, Post, 3-Month Follow-up). Change in narcissism was examined at multiple levels of its factor hierarchy (Weiss et al., 2019). To examine granular components of narcissism (i.e., agentic extraversion, narcissistic antagonism), we used two explicit measures of narcissism, namely the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Gentile et al., 2013) and the Psychological Entitlement Scale (PES; Campbell et al., 2004). Only self-report data at baseline and 3-month follow-up were collected for these measures. Our primary aim was to examine ayahuasca-induced changes in these components, given the validity of the explicit measures and the homogeneousness of the factors relative to higher order factors. The NPI has demonstrated notable convergence with clinical measures of NPD (Miller et al., 2009) as well as features of pathological narcissism, including entitlement, psychopathy, and externalizing behaviors (Krusemark et al., 2018).

To examine pathological narcissism, we created a proxy composite of DSM-5 NPD using FFM personality facets rated highly by NPD experts and clinicians in describing NPD. FFM facets that were rated to describe NPD were used to create an average FFM composite score for each participant. Both self-reported and informant-reported FFM data were collected at baseline, post, and 3-month follow-up. Informant-report data refers to ratings of personality that participants’ close significant others (e.g., spouses, family members, friends) completed about each participant.

Although FFM personality can be used to index lower order components of narcissism as well, this approach would have been duplicative with previously published results (Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021). In line with previous personality-based work, we hypothesized decreases in narcissistic traits with highest relevance to Antagonistic Externalizing (NPI Entitlement-Exploitativeness; PES Entitlement) and increases in agentic extraversion-related traits (NPI Leadership Authority; NPI Grandiosity-Exhibitionism). The secondary aim was to similarly examine change in the NPD composite, derived from patient and expert ratings of personality facets associated with NPD.

An additional aim was to investigate factors that may affect the degree of personality change found in relation to psychedelic experience. Specifically, we examined the degree to which differences in narcissism outcomes between timepoints varied as a function of validity variables (suggestibility, expectancy), individual characteristics at baseline (e.g., age, sex), drug conditions (e.g., use of additional psychedelic substances, dosage, number of ceremonies), and acute experience factors (ego dissolution, mystical experience). Given the absence of a control or comparison group, to test the validity of the results, we tested whether higher suggestibility and expectancy for positive personality changes could better account for changes in narcissism.

METHODS

PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT AND ENROLLMENT

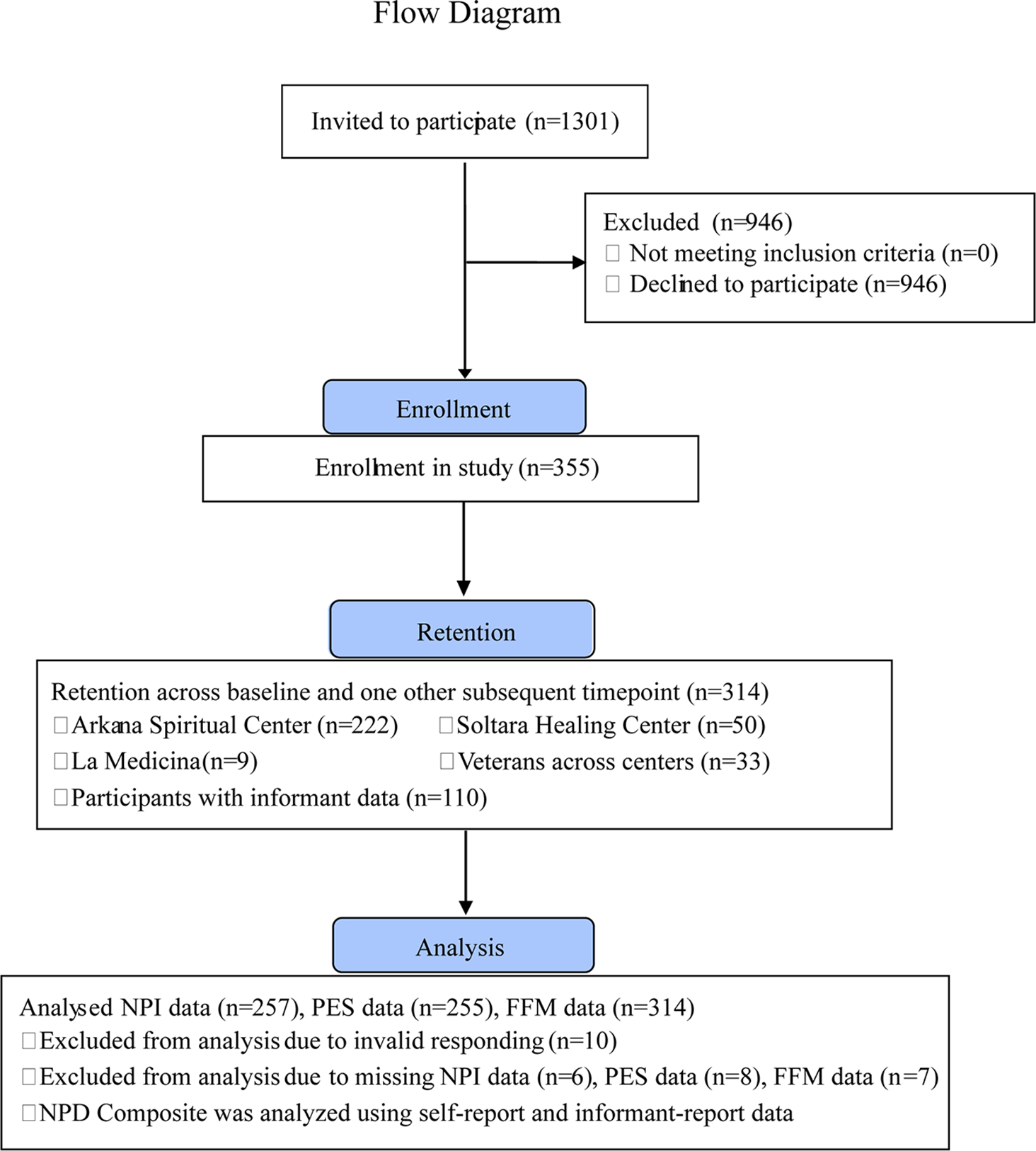

A total of 1,301 individuals who had reservations at three ayahuasca retreat centers across Central and South America were invited to participate: Arkana Spiritual Center (Requena, Loreto, Peru), Soltara Healing Center (Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica), and La Medicina (Cordilliera Escalera mountain range, Peru); 355 participants enrolled. Further information regarding study enrollment and retention can be found in Figure 1. Sample size was determined on the basis of obtaining statistical power to detect a change in outcome measures of at least .20 standard deviations. Only individuals aged 18 years or older were included, but no exclusion criteria were specified in this observational study. Intake directors for participating retreat centers, however, mandated that attendees taper off from antidepressant use (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and be abstinent within 2 weeks of retreat participation. In addition, the directors excluded candidates with a personal or family history (first or second degree) of psychotic disorders. Standing on narcissistic traits was not an inclusion criterion.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study enrollment, retention and analysis

STUDY DESIGN

Explicit measures of narcissism were conducted at two timepoints (baseline, 3-month follow-up); participants completed FFM assessments at three timepoints (baseline, post, 3-month follow-up); and informants (or peers) of participants completed FFM assessments about the participants at two timepoints (baseline, 3-month follow-up). Participants were enrolled between December 2016 and June 2021, and the 3-month follow-up outcome assessments were completed in September 2021. Data from this sample have been used in other studies (Agin-Liebes et al., 2022; Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021), but the questions and variables examined in the present study are novel. Specifically, results related to NPI, PES, and NPD composite scores have not been reported before; however, the FFM traits and facets that make up the FFM NPD composite have been individually reported on in previous work (Weiss, Miller, et al., 2021). Information about participant compensation, compliance, and procedure can be found in the supplementary materials. All procedures were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board.

PARTICIPANT COMPENSATION, COMPLIANCE, AND PROCEDURE

Participants were e-mailed 2 weeks before the date of their retreat with an invitation and were informed they would be compensated with a personality change report and entry into a raffle for a week-long retreat at Arkana Spiritual Center (valued at $1,580). The baseline survey asked participants to include contact information of close significant others (informants), who were subsequently contacted with an informant survey containing FFM personality measurements. Informed consent was obtained from both participants and informants using an online Qualtrics survey. On average, participants filled out the baseline survey 8 days before the beginning of the retreat (SD = 6.85 days). On the first day of the retreat, participants were provided with a link to the post survey. On the last day of the retreat, participants were reminded to complete the post survey. Of two reminder e-mails, the second e-mail offered participants $20.00 in compensation for completing the survey. On average, participants filled out the post survey 5 days following the end of the retreat (SD = 4.93 days). Three months following the last day of the retreat, participants were provided with the 3-month follow-up survey, and, for FFM measures, informants were invited to rate target participants’ personality for the second time. Up to three reminder e-mails were subsequently sent. The second and third reminder e-mails offered incentives of $20.00 and $30.00, respectively, to complete the survey. On average, participants filled out the follow-up survey 18 days following their invitation (SD = 18.32 days).

CEREMONY ACTIVITIES

All three retreats host shamans from the Shipibo lineage (originating in the west Amazon basin). Among the ceremonies offered, the ayahuasca ceremony (offered three to four times each week) represents the most time-intensive practice. All participants took part in the ayahuasca ceremony and sharing circles (i.e., group sessions in which individuals share about their experiences and therapeutic process), whereas the ceremonial use of bufo (Bufo alvarius toad venom containing 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine [5-MEO-DMT]), huachuma (or San Pedro cactus containing 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine mescaline), as well as nunu (tobacco and ash snuff), flower baths, and kambo (a purgative frog venom) were conditionally available to participants depending on the retreat center and its offerings at a given time. For information about the frequency of participants’ use of psychedelic plant medicines, see Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.1 (9.7) |

| Male | 203 (65.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 263 (85.1) |

| White (Hispanic) | 21 (6.8) |

| Black | 7 (2.2) |

| Asian | 18 (5.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (0.6) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 11 (3.5) |

| Income | |

| $0-$30,000 | 68 (22.1) |

| $30,000-$60,000 | 88 (28.6) |

| $60,000-$90,000 | 49 (15.9) |

| $90,000-$120,000 | 42 (13.6) |

| $120,000 or more | 61 (19.8) |

| Educational level | |

| Some high school | 86 (2.8) |

| High school (or GED) | 122 (39.1) |

| Some college | 51 (16.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 (4.8) |

| Master’s degree | 31 (9.9) |

| Doctoral degree | 6 (1.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single (never married) | 156 (50.0) |

| Married | 63 (20.2) |

| Separated | 12 (3.8) |

| Divorced | 42 (13.5) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.0) |

| Long-term domestic partner (> one year) | 36 (11.5) |

| Self-reported psychiatric diagnosis | |

| Depressive disorder | 38 (24.4) |

| Anxiety disorder | 20 (12.8) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 32 (20.5) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 4 (2.6) |

| Other mental health disorder | 6 (5.1) |

| Unique participants with mental health disorder | 51 (40.4) |

| Lifetime psychedelic use | |

| 0 | 51 (16.2) |

| 1 | 25 (8.0) |

| 2–4 | 69 (22.0) |

| 5–10 | 66 (21.0) |

| >10 | 103 (32.8) |

| Lifetime ayahuasca use | |

| 0 | 230 (81.3) |

| 1 | 13 (4.6) |

| 2–4 | 17 (6.0) |

| 5–10 | 14 (4.9) |

| >10 | 9 (3.2) |

| Number of weeks at retreat | |

| 1 | 216 (68.8) |

| 2 | 77 (24.5) |

| 3 | 21 (6.7) |

| Ceremonies attended during retreat | |

| 1–3 | 101 (34.9) |

| 4–6 | 128 (44.3) |

| 7–9 | 50 (17.3) |

| 10–13 | 10 (3.5) |

| Ceremonies where ayahuasca was ingested | |

| 1–3 | 112 (40.6) |

| 4–6 | 111 (40.2) |

| 7–9 | 44 (15.9) |

| 10–12 | 9 (3.3) |

| Average amount of ayahuasca ingested per ceremony | Glass 50% to 85% filled |

| Additional substances used during retreat | |

| Huachuma (containing Mescaline) | |

| 0 | 117 (46.4) |

| 1 | 115 (45.6) |

| 2 | 18 (7.1) |

| 3 | 2 (0.8) |

| Bufo (containing 5-MEO DMT) | |

| 0 | 130 (51.6) |

| 1 | 110 (43.7) |

| 2 | 10 (4.0) |

| 3 | 2 (0.8) |

Note. Data based on the FFM data (n = 314).

MEASURES

Primary Outcomes (Self-Report)

Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

The 13-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory 13 (NPI-13; Gentile et al., 2013) was adapted to contain a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree) to increase variability and internal consistency (Miller et al., 2018), and indexes three parsimonious factors identified by Maxwell and colleagues (2011): (a) Entitlement-Exploitativeness (EE; αT1 & αT3 = .61; e.g., “I find it easy to manipulate people”), which served as our primary measure of narcissistic antagonism; (b) Grandiose-Exhibitionism (GE; αT1 = .76; αT3 = .74; e.g., “I like to show off my body”); and (c) Leadership-Authority (LA; αT1 = .74; αT3 = .72; e.g., “I like having authority over other people,” “I am a born leader”). The latter two factors served as measures of Grandiose Narcissism and agentic extraversion. Subscale mean scores were computed for each participant.

Entitlement.

The nine-item self-report Psychological Entitlement Scale (PES; Campbell et al., 2004) served as a second measure of narcissistic antagonism (αT1 = .85; αT3 = .87, “I deserve more things in my life”). Entitlement has been linked to interpersonal consequences, including aggression and resource acquisitiveness (e.g., Campbell et al., 2004). A 7-point Likert scale was used (1 = Strong disagreement, 7 = Strong agreement). Reverse-scoring of relevant items was conducted and mean scores were computed for each participant.

Drawing on hierarchical models of narcissism (e.g., TMN), NPI Entitlement-Exploitativeness and PES Entitlement are regarded as indices of narcissistic antagonism, whereas NPI Leadership-Authority is regarded as an index of agentic extraversion, and NPI Grandiose-Exhibitionism is regarded as an index of Grandiose Narcissism more broadly (reflecting agentic extraversion and self-centered and immodest aspects of antagonism). An overview of where outcomes fit into the Trifurcated Model of Narcissism can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Instantiation of Outcomes in Trifurcated Model of Narcissism

| Measured Outcome | Neuroticism | Antagonism | Agentic Extraversion |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| NPD Composite | Narcissistic Personality Disorder | ||

| Narcissistic Personality Inventory | Grandiose-Exhibitionism Entitlement-Exploitativeness | Leadership-Authority Grandiose-Exhibitionism | |

| Psychological Entitlement Scale | Entitlement | ||

Note. Trifurcated Narcissism Inventory (Weiss et al., 2019); Narcissistic Personality Inventory = Raskin & Terry, 1988; Psychological Entitlement Scale = Campbell et al., 2004; Source: OSF.IO/2UA35 under CC0 1.0 Universal.

Secondary Outcomes (Self-Report and Informant Report)

Five-Factor Model (of Personality) Narcissistic Personality Disorder Composite.

Our secondary outcome was response to ceremony on NPD at post and 3-month follow-up for self-report data, and response at 3-month follow-up for informant-report data. To score the NPD composite, we used the FFM Personality Disorder count method as described by Miller (2012). Specifically, a composite of NPD was constructed using facet scores that bear the greatest relevance to NPD.

Facet scores were measured using two well-validated measures of FFM personality: the International Personality Item Pool-120 (IPIP-NEO-120; Maples et al., 2014; administered to participants, self-report) and the IPIP-NEO-60 (Maples-Keller et al., 2019; administered to informants, informant report) using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree).2 To be clear, participants were asked to rate their own personality, whereas informants were asked to rate participants’ personality.

Relevance was determined on the basis of empirical meta-analytic relations between NPD and FFM facets (Samuel & Widiger, 2008), as well as academic and clinician ratings of NPD using FFM items (Lynam & Widiger, 2001; Samuel & Widiger, 2004). Facets for the NPD composite were selected and mean-scored that were rated by academics and/or clinicians at below 2 or above 4 on a 5-point Likert scale.

Facets selected for NPD included Angry Hostility (N2, High), Self-conscious (N4, Low), Warmth (E1, Low), Assertiveness (E3, High), Activity (E4, High), Excitement-seeking (E5, High), Actions (O4, High), Trust (A1, Low), Straightforward (A2, Low), Altruism (A3, Low), Compliance (A4, Low), Modesty (A5, Low), and Tendermindedness (A6, Low) (see Weiss & Miller, 2018, for condensed FFM rating information). The following were internally consistent: self-report data: αT1 = .45; αT2 = .50; αT3 = .49; informant report: αT1 = .52; αT3 = .45. Suboptimal internal consistency is considered acceptable in this context given that the NPD composite contains heterogeneous components of personality.

Acute Experience Variables

Ego Dissolution Inventory.

The Ego Dissolution Inventory (EDI; Nour et al., 2016) was used to measure dissolution of the ego during the acute effects of ayahuasca. The EDI consists of eight items (e.g., “I experienced a disintegration of my ‘self’ or ego”) using a 5-point Likert scale to measure the presence of dissolution phenomena (1 = No more than usually, 5 = Yes, much more than usually). Internal consistency was good (α=.89). Mean scores were computed for each participant.

Mystical Experience Questionnaire.

The Revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ; Barrett et al., 2015; MacLean, Leoutsakos, Johnson, & Griffiths, 2012) was used to assess mystical aspects of participants’ experiences during ceremonies. The MEQ consists of 30 items originally represented on the Pahnke–Richards Mystical Experience Questionnaire (Pahnke, 1969; Richards, 1975). The MEQ total score was used for the present study, but the scale contains four factors: (a) Mystical (e.g., “Experience of the fusion of your personal self into a larger whole”), (b) Positive mood (e.g., “Sense of awe or awesomeness”), (c) Transcendence of time and space (e.g., “Loss of your usual sense of space”), and (d) Ineffability (e.g., “Sense that the experience cannot be described adequately in words”). Items asked participants to consider the degree to which they had experienced the preceding phenomena at any time during their ayahuasca ceremonies. Items used a 6-point Likert scale (1 = None; Not at all, 6 = Extreme [more than any other time in your life and stronger than 4]). One of the items from the Mystical subscale (MEQ Item 30) was excluded due to administrator error. Nevertheless, internal consistency was still extremely high (α = .96). Mean scores were computed for each participant.

Validity Variables

Experiential Factor Validity Items.

An original three-item scale was used to measure overreporting of acute mystical-type experiences using the same response scale as the MEQ. Participants were asked the degree to which they experienced the following low base-rate phenomena: “Experience of a distant childhood friend you have not seen or thought of in a long time,” “Rapidly fluctuating pattern of feelings alternating from joy to sadness and back again,” and “Experience of bodily fragmentation, such that parts of your body are separated from one another.” The cutoff for invalid responding was defined as strong or extreme endorsement of all three validity items. On the basis of this cutoff, data for measures indexing acute experience were excluded for 11 participants.

Invalid responding.

Two eight-item validity scales from the Elemental Psychopathy Assessment (Lynam et al., 2011) were used to detect invalid responding on measures of personality. These scales were the Infrequency scale and the Unlikely Virtue scale. A 5-point Likert scale was used (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). In line with guidelines, participants who endorsed more than three Infrequency scale items and more than two Unlikely Virtue scale items were eliminated.

Suggestibility.

The 21-item Multidisciplinary Iowa Suggestibility Scale-Short (MISS; Kotov et al., 2004) was used to measure participants’ susceptibility to internalize external influences (e.g., “When making a decision, I often follow other people’s advice”). The MISS uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree), and exhibited internal consistency of α = .84. Mean scores were computed for each participant.

Expectancy.

An original scale was developed consisting of 10 yes/no items measuring expected change in Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Agreeableness (e.g., “I will become more agreeable, i.e., will become more considerate, kind, generous, trusting and trustworthy, helpful, and willing to compromise”) and spirituality (“I will become more spiritual”).

Lifetime Use of Psychedelic Compounds.

Participants were asked to report previous use of classic psychedelic compounds and previous ceremonial use of ayahuasca. These variables were dichotomized to reflect the presence or absence of previous psychedelic experience.

Long-Term Adverse Cognitive Effects

At 3-month follow-up, participants were asked to report the occurrence of any cognitive side effects following their retreat that they attributed to their ayahuasca experience (“Have you noticed any cognitive side effects [negative or positive; e.g., concentration, holding thoughts in your head, any speech impairment] that you associate with your ayahuasca experience? If so, please feel free to elaborate below”). Because knowledge of the effects of ayahuasca remains at an early stage of development, we believed it was important to include these adverse cognitive effects along with other trait-based changes in narcissism. Participants’ open-ended responses were reviewed and recorded.

ANALYTIC PLAN

Analyses were conducted using the ‘lme’ package (Bates et al., 2015) in R software. Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using linear mixed effect (LME) models (equivalent to one-way repeated measures ANOVA), where repeated measurements were nested within participants. For secondary outcomes involving FFM NPD composites in self-report data, omnibus tests of differences between three timepoints were first analyzed. Where a significant main effect was observed, post hoc comparisons were conducted between each timepoint.

Moderators were additionally tested regarding validity variables (expectancies, suggestibility), individual characteristics at baseline (sex, age, education level, parental income), drug conditions (e.g., use of additional psychedelic substances, dosage, number of ayahuasca ceremonies, and acute subjective factors (mystical experience, ego dissolution). For moderation-based analyses, each moderator was separately added as a fixed covariate to each base model (including the fixed effect of time). The only exception was that moderation-based analyses were not conducted for the NPD composite in informant-report data, because our statistical power was considered to be low.

For primary outcomes, a significance threshold of p < .05 was set (4 analyses). Secondary analyses were judged using a threshold of p < .001 to balance Type I and Type II errors.

Cohen’s ds (standard Cohen’s d) effect size estimates were calculated using the following equation: (Mean scoreT2 − Mean scoreT1)/((SDT1)2 + SDT2)2)0.5. Cohen’s dz effect size estimates (for one-sample within-subjects designs) were calculated by dividing the mean difference of personality scores between two timepoints by the standard deviation of differences in scores between the same two timepoints. Unstandardized (B) coefficients were used to indicate mean differences between timepoints.

POWER ANALYSIS

Sensitivity power analyses (using “simr” R package) were conducted to assess the smallest effects that could be found in our sample for main effect analyses. Effect sizes sufficient to obtain 80% statistical power (using 100 Monte Carlo simulations) were estimated. The self-report sample was powered to detect true (main effect of time) differences between timepoints exceeding .12 standard deviations for NPI EE, NPI GE, NPI LA, and PES (alpha value of p = .05); and exceeding .17 standard deviations for NPD (alpha value = .001). The informant sample was powered (80%) to detect true (main effect of time) differences between timepoints exceeding .27 for the NPD composite (alpha value = .001).

RESULTS

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

Of the 355 participants who were recruited, 3% (n = 10) met criteria for invalid responding based on the validity scales, and 9% (n = 31) completed only the baseline assessment. Additional participants were excluded due to missing NPI, PES, or FFM data (see Figure 1 for precise numbers). All data met assumptions of normality according to guidelines indicated by Hair and colleagues (2010) and Bryne (2010).

The final sample consisted of 257 and 255 participants who provided NPI and PES data (respectively) for baseline and 3-month follow-up, and 314 participants who provided FFM data for baseline and either or both post and 3-month follow-up. Retention of participants for all relevant timepoints was approximately 84% across these subsamples (see Figure 1 for flow diagram).

Of the 314 participants who provided self-report FFM data, 33% (n = 104) possessed informant-report measurement at baseline and 3-month follow-up, and an additional six cases of informant data were used from participants who were eliminated from self-report data due to invalid responding, yielding an informant-report sample of 110 participants. Data were computed by averaging across informants at the item-level for each timepoint. The number of informants per participant ranged from one to three. Independent-samples t-test analyses were conducted to test for differences between “participants with informant data” (N = 110) and “participants without informant data” (N = 165). No significant differences were found. At baseline, participants with missing data differed from participants with full data only on the basis of lower FFM Conscientiousness scores (d = .34, p = .014). Means, standard deviations, and range for outcomes are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 2 (based on NPD composite subsample, n = 314). On average, participants were predominantly White (85%), upper-middle class in terms of economic status (e.g., 49% exhibited income > $60K), and of lower educational attainment (e.g., 58% had not completed college).

To understand the standing of our participants on narcissistic traits, sample means were compared to normative data from the literature. The present sample was compared to (a) adults recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (N = 264; Miller et al., 2018, Sample C Likert assignment), (b) undergraduates (N = 918; Campbell et al., 2004) in terms of PES Entitlement, and (c) community adults (N = 501; Goldberg et al., 2006) in terms of personality facets related to NPD (see NPD Composite section below for details on these facets). Participants showed lower standing on narcissism based on the NPI EE (d = −.27) and PES (d = −.60), FFM facet Self-consciousness (d = +.31), and FFM facet Activity (d = −.41), whereas they showed higher standing on narcissism based on NPI GE (d = +.22), and 9 of 13 NPD composite facets including four of six agreeableness facets. Participants were notably equivalent to community adults in terms of FFM facet Modesty, which represents a particularly core attribute of narcissism. Detailed normative comparisons are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

In sum, our sample showed some evidence of higher standing on narcissism, but explicit measures indicated lower standing on narcissistic antagonism, which is considered to be the core of narcissism with the highest relevance to Antagonistic Externalizing. Although the sample cannot be said to be concentrated with high levels of narcissistic antagonism or Antagonistic Externalizing, examination of psychedelic-induced changes in narcissism are nonetheless considered valid and informative given the dimensionality of these traits, as demonstrated by taxometric analyses (Aslinger et al., 2018; Foster & Campbell, 2007).

No participants in our sample reported a lifetime diagnosis of NPD. However, approximately 40% reported a lifetime diagnosis of a mental health disorder, with 24% endorsing a lifetime diagnosis of a depressive disorder, 21% posttraumatic stress disorder, and 13% anxiety disorder.

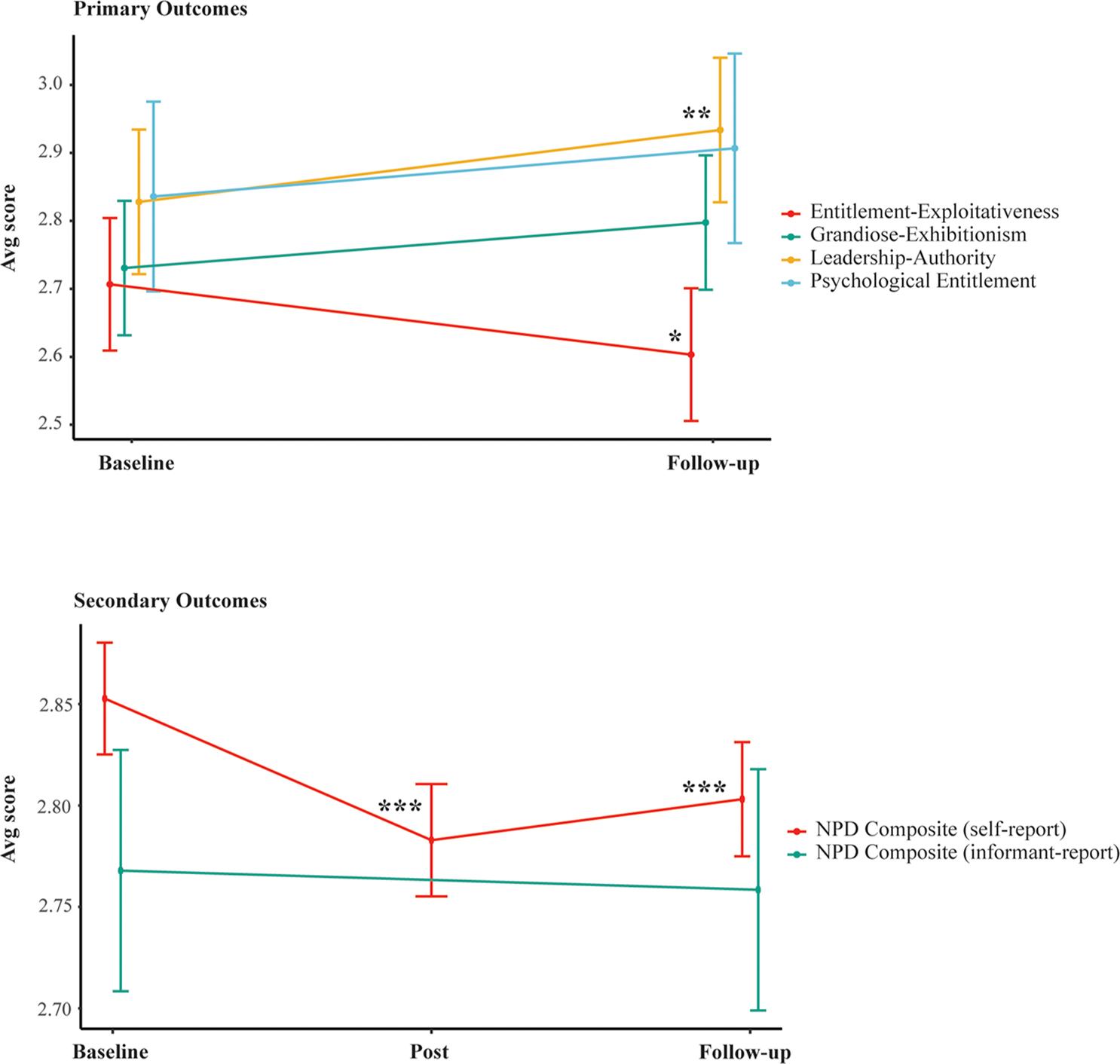

PRIMARY OUTCOMES: EXPLICIT MEASURES POSTCEREMONY RESPONSE

Main effects of timepoint were observed on NPI Entitlement-Exploitativeness (B = −.10, 95% CI [−.18, −.03], p = .020, dz = −.15, ds = −.08) and NPI Leadership Authority (B = .11, 95% CI [.03,.18], p = .004, dz = .18, ds = .09). Specifically, NPI Entitlement-Exploitativeness decreased .10 units (on a 5-point Likert scale) and NPI Leadership Authority increased .11 units. Main effects of timepoint were not observed on NPI Grandiose-Exhibitionism (B = .06, 95% CI [−.01, .14], p = .075, dz = .11, ds = .06) or PES (B = .09, 95% CI [−.02, .19], p = .126, dz = .10, ds = .05). These results are displayed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes. Line plots illustrating change in outcomes over time. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals around means. Asterisks denote significant differences between baseline and post, and baseline and 3-month follow-up. *p < .05. **p < .005. ***p < .001.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES: FFM-BASED NARCISSISM COMPOSITES

In self-report data, a main effect of timepoint was observed on the NPD composite, F(2, 587) = 25.72, p < .0001. Post hoc tests demonstrated that NPD composite scores were lower within a week following a ceremony (B = −.07, 99.9% CI [−.10,−.04], p < .0001, dz = −.39, ds = −.19) and 3 months following a ceremony (B = −.05, 99.9% CI [−.08,−.02], p < .001, dz = −.27, ds = −.15). In informant-report data, no main effect of timepoint was observed on NPD composite scores (B = −.01, 99.9% CI [−.08, .06], p = .649, dz = −.04; ds = −.02). These results are displayed in Figure 2.

As a note, the self-reported NPD composite showed a moderate correlation with the informant-reported NPD composite (rT1 = .39, rT3 = .39, p < .005).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES: MODERATION-BASED ANALYSES

No moderation-based effects were observed across examined outcomes and moderators. It may nevertheless bear noting some interactions that showed trend-level (p < .05) significance. These included associations between using Bufo and an incremental increase in PES (p = .03), between retreat length and an incremental increase in PES (p = .02), and between average dose of ayahuasca and an incremental increase in NPD composite score (p = .01). Given that the number of these significant cases represents 3.8% of analyses, well below the 5% Type I error rate, we will not be interpreting these results. Full moderation-based results are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

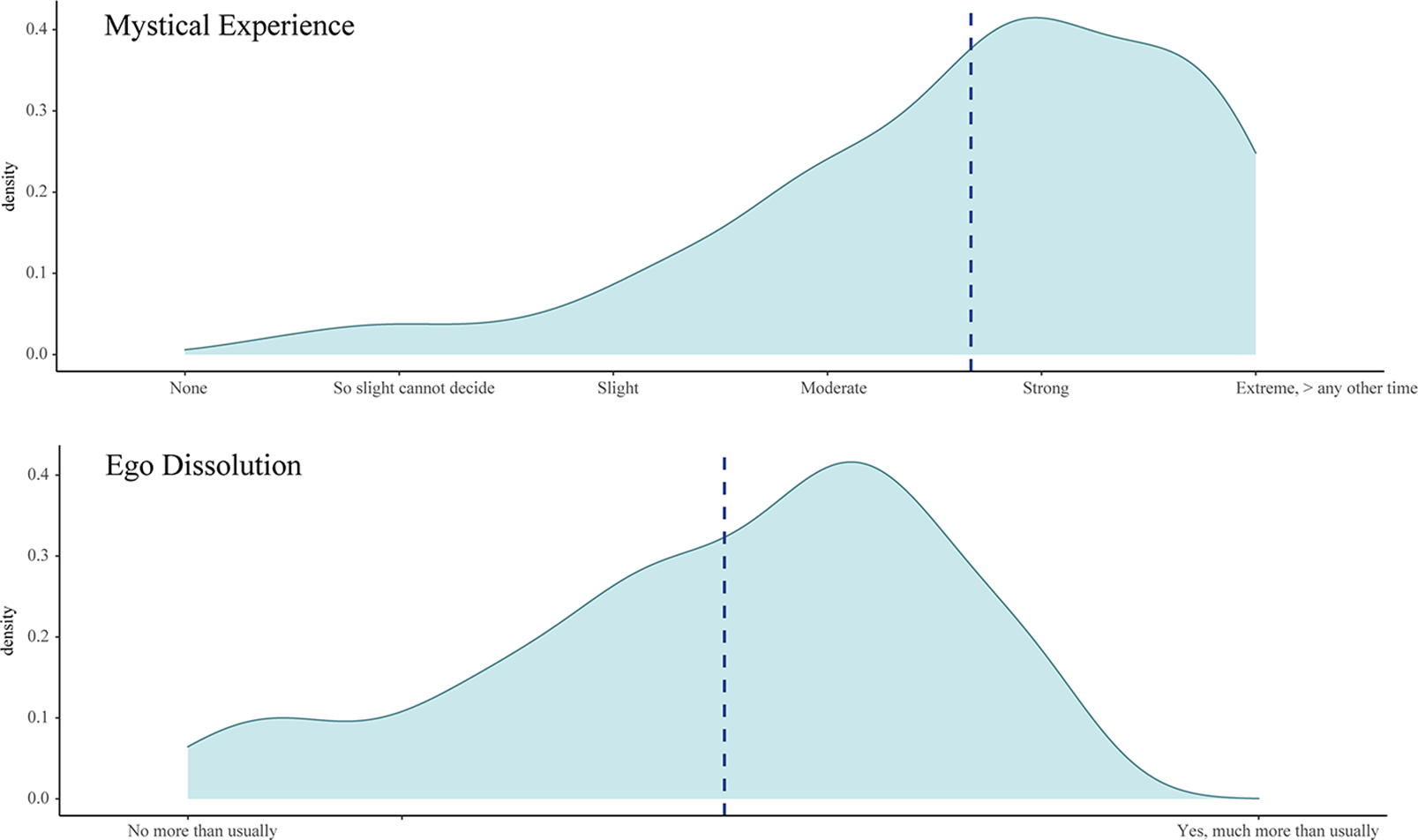

EXAMINING ACUTE EXPERIENCE

Acute experience variables were also examined to investigate potential explanatory factors for observed changes in narcissism. With respect to MEQ Mystical Experience, participants exhibited a mean mean-score of 4.67 (corresponding to a score between moderate and strong in terms of degree of experience on a 6-point Likert scale), 1.01 standard deviation, and range of 1.35 to 6.00. With respect to EDI Ego Dissolution, participants exhibited a mean mean-score of 3.51 (on a 1–5 5-point Likert scale), 1.04 standard deviation, and range of 1.00 to 5.00. Kernel density plots are provided in Figure 3 showing the full distribution.

FIGURE 3.

Kernal density plots of MEQ Mystical Experience and EDI Ego Dissolution mean mean-scores. Dotted line indicates mean score for the sample. Sample N = 284.

LONG-TERM ADVERSE HEALTH EFFECTS

Among a subset of 188 participants (60% of the full NPD sample) who were asked to report on possible negative side effects from their ayahuasca experience at 3-month follow up, 11 participants (6% of the subsample) reported negative side effects. These side effects included difficulty relating to people (1 participant), “hypersensitivity” (1), flashbacks/recollections of adverse subjective experience during a ceremony (2), distressing dreams (1), auditory hallucination/voices (1), worsening of Hallucinogen-Persisting Perception Disorder (1), speech impairment/mispronunciation of words (2), brain fog (1), and difficulty concentrating/focusing, e.g., on mathematical/financial information (3).

DISCUSSION

The present prospective study is the first to examine the effects of psychedelic use on components of narcissism. Overall, results were nominally supportive of hypothesized decreases in narcissistic antagonism and the NPD composite, and increases in agentic extraversion. However, effects of change were generally small and not consistent across self- and informant-report measures.

Specifically, some support was found for adaptive change in narcissistic antagonism, marked by observations of decreased Entitlement-Exploitativeness (indexed by NPI EE) and decreased NPD (NPD composite) up to 3 months following ceremony experiences. However, meaningful beneficial effects of a ceremony were not observed as changes in Entitlement-Exploitativeness were small, not all antagonism-related outcomes (i.e., PES) demonstrated change, and decreased NPD was not reflected in informant-report data.

Furthermore, the ceremonial use of ayahuasca was associated with minimal enhancement in certain psychologically healthier elements of grandiose narcissism related to perceived leadership ability (NPI LA “I am a born leader”; B = .18) and authority (NPI LA “People always seem to recognize my authority”; B = .19), whereas changes in more maladaptive aspects of grandiose narcissism involving grandiosity, exhibitionism, and immodesty (indexed by NPI GE) were not observed. These results are consistent with previous findings showing psychedelic-induced increases in extraversion (e.g., Erritzoe et al., 2018), and may be demonstrative of beneficial effects of ceremonies. Leadership- Authority is empirically linked to adaptive functioning (e.g., psychological resilience, social potency, lower neuroticism; Ackerman et al., 2011), and Grandiose Narcissism is broadly linked to positive life outcomes, including life satisfaction (Kaufman et al., 2020). However, it is not clear that these effects are meaningful given their small size. Future research is also needed that probes whether these changes are reflective of increased spiritual superiority or ego inflation. On balance, our investigation into Grandiose Narcissism and agentic extraversion is considered inconclusive given that changes were minimal, and that changes in NPI LA were limited to self-report data.

Notably, ego dissolution and mystical experiences were not observed to moderate changes in antagonism, agentic extraversion, or NPD. These results provide preliminary evidence that alterations in self-conception as well as unitive experiences accompanying psychedelic experience may not be connected to processes underlying the Antagonistic Externalizing spectrum of psychopathology.

Collectively, our results provide modest and qualified signs of the utility of psychedelic-assisted therapies for the treatment of NPD and antagonistic externalizing. More research would be needed, in particular, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies tailored to this population, monitoring of personality earlier than 3 months, and, most importantly, controlled studies containing samples with clinical levels of antagonistic externalizing. At present, studies generally exclude such individuals in order to optimize remediation of internalizing psychopathology via greater therapeutic rapport (e.g., Carhart-Harris et al., 2021). When evaluating the treatment utility of the ceremonial use of ayahuasca, it is also important to weigh the incidence of long-term adverse events (including intrusive reexperiencing, auditory hallucinations, difficulty concentrating, speech impairment; occurring in 6% of participants) against its therapeutic benefits.

DISCREPANCY BETWEEN SELF- AND INFORMANT DATA

It is also important to explore possible reasons for lack of agreement between observed changes in NPD between self-report and informant-report data. On one hand, lack of agreement raises questions regarding the validity of self-report NPD composite measurement. One possible explanation for the discrepancy is that self-ratings may be more vulnerable to placebo effects, which have been demonstrated in the context of psychedelic drug use (Olson et al., 2020). It will therefore be important for future research to replicate these findings using a more rigorous placebo-controlled design (Aday et al., 2022).

On the other hand, agreement between participants and informants on participants’ NPD standing was relatively poor (r < .40). This could stem from the NPD composite’s concentration with agreeableness facets (6 of 13 NPD composite facets), which similarly showed poor observed agreement between participants and their informants in previous work (r < .40; see Weiss et al., 2021, supplementary materials). That participants and informants differed in their assessment of participants’ NPD suggests that we would not necessarily expect concordance in terms of ratings of change over time. Although it is possible that informant data may be more accurate than self-report data for NPD, only extraversion (representing 4 of 13 NPD composite facets) has demonstrated greater accuracy by peers, on the basis of its observability (Vazire, 2010). Furthermore, although we asked participants to select informants who spent time with them on more days than not during the week, it is possible that in many cases informants were selected who were able to observe them for less time, influencing rating accuracy.

In sum, although self-report data may be more susceptible to placebo-related biases, there are not strong empirical reasons to favor informant-report data over self-report data in the measurement of NPD. Nevertheless, lack of agreement still amounts to a reason to be conservative in interpreting self-report NPD findings. In future research, it would be useful for informant data to be collected for all measures, including explicit measures of narcissism, and we encourage more informant-report measurement in the psychedelic research space.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study has notable strengths. It is the first serious investigation of psychedelic effects on narcissism in a prospective manner. Methodological safeguards were employed to reduce placebo, expectancy, and demand threats, including measurement and control of suggestibility and expectancies, follow-up measurement, and informant-data corroboration. Finally, the study contained a relatively large and well-powered sample, and, unlike predominant survey work in the field, contained an acceptable level of attrition (~16%) that limits sample bias.

This study nevertheless has several limitations, the most important of which is the absence of a placebo control group in the study, which the naturalistic design of the study precluded. Second, although we comment on the utility of ceremony for clinical presentations of personality pathology, our sample was healthy with the notable exception of 40% of the sample that reported a lifetime mental health disorder (that did not include NPD). It will be important for future research to explore therapeutic efficacy in a sample of individuals with clinical levels of antagonistic externalizing/NPD. Third, explicit clinical measures of NPD were not administered, and FFM-derived proxy measures are not optimally suitable for examining clinical therapeutic effects. Fourth, where explicit measures of narcissism were used, informant data was not collected to corroborate these changes. Fifth, while the study sample was relatively diverse with regard to educational backgrounds, participants were primarily White and middle to upper-middle class. Further research with more diverse samples is still needed. Sixth, although this study comprises the largest prospective sample to date in the ayahuasca literature, the generalizability of our findings to the larger population remains limited by the unique cohort of retreat-going adults we recruited. Randomized controlled research, including large samples of participants without a strong interest in ayahuasca per se, is needed to assist generalizability. Finally, it is not known to what degree 5-MEO DMT and mescaline contributed to the observed effects, as a subset of participants used these compounds in addition to ayahuasca. We applied moderation to address these effects and found negligible evidence for differential effects, but future research remains necessary to critically compare each compound on its own.

CONCLUSION

The present study represents the first serious inquiry into prospective psychedelic-induced change in narcissistic traits. Therapeutic effects on narcissistic antagonism and an FFM-based NPD proxy measure were small in size where present, and mixed. An observed effect on agentic extraversion was similarly small in size. These results provide modest and qualified evidence for the possible relevance of psychedelic-assisted therapy to the Antagonistic Externalizing spectrum of psychopathology. With respect to the clinical implications of this work, our results are considered sufficiently substantive to warrant further investigation. Future research should examine these questions in a clinical trial comprised of participants manifesting higher levels of narcissism/antagonistic externalizing psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who contributed their valuable time to this study. This work could not have been possible without the support of R.L.B., Soltara Healing Center, La Medicina, Arkana Spiritual Center, Heroic Hearts Project, and the Source Research Foundation.

All opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Source Research Foundation, Soltara Healing Center, La Medicina, Arkana Spiritual Center, or Heroic Hearts Project.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online.

The VA had no role in the study design, in the collection analysis and preparation of data, or in the writing of the article; nor do the views expressed in this article necessarily reflect those of the United States government or the VA.

Distortions in an individual’s sense of self occasioned by a psychedelic experience have also been termed “ego death” (Grof, 1980; Harrison, 2010), “ego-loss” (Leary et al., 1964), and “ego-disintegration” (Lebedev et al., 2015; Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2013).

FFM personality domains include Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness.

Contributor Information

Brandon Weiss, Imperial College London, Division of Psychiatry, London, United Kingdom.

Chelsea Sleep, Veteran Affairs Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Joshua D. Miller, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia..

W. Keith Campbell, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia..

REFERENCES

- Ackerman RA, Witt EA, Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, & Kashy DA (2011). What does the Narcissistic Personality Inventory really measure? Assessment, 18(1), 67–87. 10.1177/1073191110382845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday JS, Heifets BD, Pratscher SD, Bradley E, Rosen R, & Woolley JD (2022). Great expectations: Recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trials. Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1989–2010. 10.1007/s00213-022-06123-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agin-Liebes G, Zeifman R, Luoma JB, Garland EL, Campbell WK, & Weiss B (2022). Prospective examination of the therapeutic role of psychological flexibility and cognitive reappraisal in the ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36, 295–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslinger EN, Manuck SB, Pilkonis PA, Simms LJ, & Wright AG (2018). Narcissist or narcissistic? Evaluation of the latent structure of narcissistic personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(5), 496–502. 10.1037/abn0000363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa PCR, Cazorla IM, Giglio JS, & Strassman R (2009). A six-month prospective evaluation of personality traits, psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in ayahuasca-naïve subjects. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett FS, Johnson MW, & Griffiths RR (2015). Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29, 1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PC, & Strassman RJ (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Ross S, Bhatt S, Baron T, Forcehimes AA, Laska E, Mennenga SE, O’Donnell K, Owens LT, Podrebarac S, Rotrosen J, Tonigan JS, & Worth L (2022). Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(10), 953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WK, Bonacci AM, Shelton J, Exline JJ, & Bushman BJ (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83, 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WK, Bush CP, Brunell AB, & Shelton J (2005). Understanding the social costs of narcissism: The case of the tragedy of the commons. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1358–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, Day CM, Erritzoe D, Kaelen M, Bloomfield M, Rickard JA, Forbes B, Feilding A, Taylor D, Pilling S, Curran VH, & Nutt DJ (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: An open-label feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619–627. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16) 30065-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, Martell J, Blemings A, Erritzoe D, & Nutt DJ (2021). Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402–1411. 10.1056/NEJMoa2032994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Bolstridge M, Williams TM, Williams LT, Underwood R, Feilding A, & Nutt DJ (2016). The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psychological Medicine, 46(7), 1379–1390. 10.1017/S0033291715002901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J (2003). Epidemiology, public health and the problem of personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(S44), s3–s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEOFFI) professional manual. PAR. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe ML, Lynam DR, Campbell WK, & Miller JD (2019). Exploring the structure of narcissism: Toward an integrated solution. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1151–1169. 10.1111/jopy.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, Finan PH, & Griffiths RR (2021). Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 481–489. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan N, Kunik ME, Oldham J, & Coverdale J (2010). Prevalence and treatment of narcissistic personality disorder in the community: A systematic review. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Muller F, Borgwardt S, & Liechti ME (2016). LSD acutely impairs fear recognition and enhances emotional empathy and sociality. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 2638–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, MacLean K, Kaelen M, Nutt DJ, & Carhart-Harris RL (2018). Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138, 368–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia AA, Jerome L, Yazar-Klosinski B, Emerson A, Mithoefer M, & Doblin R (2019). Breakthrough for trauma treatment: Safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy compared to paroxetine and sertraline. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 650. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstmann M, Yudkin DA, Prosser AM, Heller SM, & Crockett MJ (2020). Transformative experience and social connectedness mediate the mood-enhancing effects of psychedelic use in naturalistic settings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 2338–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Beauchaine TP, Grazioli F, Carretta I, Cortinovis F, & Maffei C (2005). A latent structure analysis of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, narcissistic personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46, 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JD, & Campbell WK (2007). Are there such things as “narcissists” in social psychology? A taxometric analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B, Miller JD, Hoffman BJ, Reidy DE, Zeichner A, & Campbell WK (2013). A test of two brief measures of grandiose narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory–13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory–16. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1120–1136. 10.1037/a0033192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR, & Gough HG (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, Cosimano MP, & Klinedinst MA (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1181–1197. 10.1177/0269881116675513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grof S (1980). LSD psychotherapy. Hunter House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J, Black WC, Babin BJ & Anderson RE (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Educational International. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J (2010). Ego death & psychedelics. MAPS Bulletin, 20(1), 40–41. https://maps.org/news-letters/v20n1/v20n1-40to41.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Clark CB, Johnson MW, Fontaine KR, & Cropsey KL (2014). Hallucinogen use predicts reduced recidivism among substance-involved offenders under community corrections supervision. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28, 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W (1882). Subjective effects of nitrous oxide. Mind, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Cosimano MP, & Griffiths RR (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28, 983–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman SB (2021, January 11). The science of Spiritual Narcissism. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-science-of-spiritual-narcissism/

- Kaufman SB, Weiss B, Miller JD, & Campbell WK (2020). Clinical correlates of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(1), 107–130. 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjærvik SL, & Bushman BJ (2021). The link between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147, 477–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov RI, Bellman SB, & Watson DB (2004). Multidimensional Iowa Suggestibility Scale (MISS). https://renaissance.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/MISSBriefManual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, Brown TA, Carpenter WT, Caspi A, Clark LA, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Goldberg D, Hasin D, Hyman SE, Ivanova MY, Lynam DR, Markon K, . . . Zimmerman M. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 454–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizan Z, & Herlache AD (2018). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22, 3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hobbs KA, Conway CC, Dick DM, Dretsch MN, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Keyes KM, Latzman RD, Michelini G, Patrick CJ, Sellbom M, Slade T, South SC, Sunderland M, Tackett J, Waldman I, Waszczuk MA, . . . HiTOP Utility Workgroup. (2021). Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): II. Externalizing superspectrum. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 171–193. 10.1002/wps.20844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusemark EA, Campbell WK, Crowe ML, & Miller JD (2018). Comparing self-report measures of grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality disorder in a male offender sample. Psychological Assessment, 30, 984–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary T, Metzner R, & Alpert R (1964). The psychedelic experience: Manual based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Penguin Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev AV, Lövdén M, Rosenthal G, Feilding A, Nutt DJ, & Carhart-Harris RL (2015). Finding the self by losing the self: Neural correlates of ego-dissolution under psilocybin. Human Brain Mapping, 36(8), 3137–3153. 10.1002/hbm.22833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Gaughan ET, Miller JD, Miller DJ, Mullins-Sweatt S, & Widiger TA (2011). Assessing the basic traits associated with psychopathy: Development and validation of the Elemental Psychopathy Assessment. Psychological Assessment, 23(1), 108–124. 10.1037/a0021146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, & Miller JD (2019). The basic trait of antagonism: An unfortunately underappreciated construct. Journal of Research in Personality, 81, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, & Widiger TA (2001). Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean KA, Leoutsakos JMS, Johnson MW, & Griffiths RR (2012). Factor analysis of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire: A study of experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 721–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maples JL, Guan AL, Carter N, & Miller JD (2014). A test of the International Personality Item Pool representation of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory and development of a 120-item IPIP-based measure of the five-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 26, 1070–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maples-Keller JL, Williamson RL, Sleep CE, Carter NT, Campbell WK, & Miller JD (2019). Using item response theory to develop a 60-item representation of the NEO PI–R using the International Personality Item Pool: Development of the IPIP–NEO–60. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(1), 4–15. 10.1080/00223891.2017.1381968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason N, Mischler E, Uthaug M, & Kuypers K (2019). Sub-acute effects of psilocybin on empathy, creative thinking and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51, 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD (2012). Five-factor model personality disorder prototypes: A review of their development, validity, and comparison to alternative approaches. Journal of Personality, 80, 1565–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Campbell WK, & Pilkonis PA (2007). Narcissistic personality disorder: Relations with distress and functional impairment. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Gaughan ET, Pryor LR, Kamen C, & Campbell WK (2009). Is research using the narcissistic personality inventory relevant for understanding narcissistic personality disorder? Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 482–488. 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Gentile B, Carter NT, Crowe M, Hoffman BJ, & Campbell WK (2018). A comparison of the nomological networks associated with forced-choice and Likert formats of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy SD, Carhart-Harris RL, Moran RJ, Brookes MJ, Williams TM, Errtizoe D, Sessa B, Papadopoulos A, Bolstridge M, Singh KD, Feilding A, Friston KJ, & Nutt DJ. (2013). Broadband cortical desynchronization underlies the human psychedelic state. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(38), 15171–15183. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzband N, Ruffell S, Linton S, Tsang WF, & Wolff T (2020). Modulatory effects of ayahuasca on personality structure in a traditional framework. Psychopharmacology, 237, 3161–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, & Carhart-Harris RL (2016). Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: Validation of the ego-dissolution inventory (EDI). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 269–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS, Steinberg PI, & Duggal S (2009). Interpersonal problems associated with narcissism among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JA, Suissa-Rocheleau L, Lifshitz M, Raz A, & Veissière SP (2020). Tripping on nothing: Placebo psychedelics and contextual factors. Psychopharmacology, 237, 1371–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke WN (1969). Psychedelic drugs and mystical experience. International Psychiatry Clinics, 5(4), 149–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, Andrade KC, Novaes MM, Pessoa JA, MotaRolim SA, Osório FL, Sanches R, Dos Santos RG, Tófoli LF, de Oliveira Silveira G, Yonamine M, Riba J, Santos FR, Silva-Junior AA, Alchieri JC, Galvão-Coelho NL, Lobão-Soares B, . . . Araújo DB. (2019). Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 655–663. 10.1017/S0033291718001356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny T, Preller KH, Kometer M, Dziobek I, & Vollenweider FX (2017). Effect of psilocybin on empathy and moral decision-making. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20, 747–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti L, Ghinassi S, & Tani F (2020). The role of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism in psychological perpetrated abuse within couple relationships: The mediating role of romantic jealousy. Journal of Psychology, 154, 144–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards WA (1975). Counseling, peak experiences and the human encounter with death: An empirical study of the efficacy of DPT-assisted counseling in enhancing the quality of life of persons with terminal cancer and their closest family members [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Catholic University of America. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter K, Dziobek I, Preissler S, Rüter A, Vater A, Fydrich T, Lammers CH, Heekeren HR, & Roepke S (2011). Lack of empathy in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 187(1–2), 241–247. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, & Schmidt BL (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1165–1180. 10.1177/0269881116675512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, & Widiger TA (2004). Clinicians’ personality descriptions of prototypic personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18, 286–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, & Widiger TA (2008). A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: a facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(8), 1326–1342. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes RE, & Hofmann A (1979). Plants of the gods: Origins of hallucinogenic use. Alfred van der Marck Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Sleep CE, Lynam DR, & Miller JD (2022). Understanding individuals’ desire for change, perceptions of impairment, benefits, and barriers of change for pathological personality traits. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 13(3), 245–253. 10.1037/per0000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaug MV, Mason NL, Toennes SW, Reckweg JT, de Sousa Fernandes Perna EB, Kuypers K, van Oorsouw K, Riba J, & Ramaekers JG (2021). A placebo-controlled study of the effects of ayahuasca, set and setting on mental health of participants in ayahuasca group retreats. Psychopharmacology, 238(7), 1899–1910. 10.1007/s00213-021-05817-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mulukom V, Patterson RE, & van Elk M (2020). Broadening your mind to include others: The relationship between serotonergic psychedelic experiences and maladaptive narcissism. Psychopharmacology, 237, 2725–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S (2010). Who knows what about a person? The self–other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 281–300. 10.1037/a0017908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk R, & Visser A (2021). An exploration of spiritual superiority: The paradox of self-enhancement. European Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z, Hendricks PS, Smith S, Kosson DS, Thiessen MS, Lucas P, & Swogger MT (2016). Hallucinogen use and intimate partner violence: Prospective evidence consistent with protective effects among men with histories of problematic substance use. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(7), 601–607. 10.1177/0269881116642538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PJ, Grisham SO, Trotter MV, & Biderman MD (1984). Narcissism and empathy: Validity evidence for the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Campbell WK, Lynam DL, & Miller JD (2019). A trifurcated model of narcissism: On the pivotal role of trait antagonism. In Miller JD & Lynam DR (Eds.), The handbook of antagonism: Conceptualizations, assessment, consequences, and treatment of the low end of agreeableness (pp. 221–236). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, & Miller JD (2018). Distinguishing between grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality disorder. In Foster JD, Brunell A, & Hermann T (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 3–13). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Miller JD, Carter NT, & Campbell WK (2021). Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Scientific Reports, 11, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Nygart V, Pommerencke LM, Carhart-Harris RL, & Erritzoe D (2021). Examining psychedelic-induced changes in social functioning and connectedness in a naturalistic online sample using the Five-Factor Model of personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 749788. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.749788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Sleep CE, Lynam DR, & Miller JD (2021). Evaluating the instantiation of narcissism components in contemporary measures of psychopathy. Assessment, 28, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff TJ, Ruffell S, Netzband N, & Passie T (2019). A phenomenology of subjectively relevant experiences induced by ayahuasca in Upper Amazon vegetalismo tourism. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 3(3), 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman RJ, & Wagner AC (2020). Exploring the case for research on incorporating psychedelics within interventions for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 1–11. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.