Abstract

Thirty-nine penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates recovered among the approximately 700 pneumococcal strains collected from 1993 to 1996 in central and northern Italy were analyzed for several characteristics, including serotype, antibiotic susceptibility profile, chromosomal relatedness (by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE]), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of the penicillin-binding protein (PBP) genes 1A, 2X, and 2B, and the presence of a variety of antibiotic resistance genes (determined by hybridization with appropriate DNA probes). The MICs of penicillin for most of the isolates (30 of 39) were high, in the range of 1 μg/ml or higher, and these 30 isolates carried additional resistance traits to two or more drugs (erythromycin, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and tetracycline) and expressed serotypes 9, 19, and 23 and three distinct PFGE patterns. More than half (22 of 30) of the isolates for which MICs were high were identified as representatives of two widespread international epidemic clones of S. pneumoniae. The first one of these clones (seven isolates) expressed serotype 23F and possessed all properties characteristic of the widespread Spanish/USA international clone. Seven additional strains with serotype 19 also had the same PFGE pattern, PBP gene, and RFLP polymorphisms, and other properties typical of the serotype 23 Spanish/USA clone, suggesting that these strains were the products of a capsular transformation event (from serotype 23F to serotype 19) in which the Spanish/USA clone was the recipient. The second international clone was represented by eight serotype 9 isolates which were resistant to penicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and had the molecular properties of the French/Spanish epidemic clone. The remaining eight isolates for which penicillin MICs were high appeared to represent a hitherto-undescribed “Italian” clone; they had a novel PFGE type, unique RFLPs for the PBP genes, and resistance to tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and erythromycin, and the penicillin MICs for these isolates were 2 to 4 μg/ml.

In contrast to other western Mediterranean countries (2–4, 8, 11, 12, 16, 17, 22, 35) and for reasons not fully understood, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae has been isolated relatively rarely in Italy (18, 19, 28). Nevertheless, the frequency of penicillin-resistant isolates appears to be on the rise in Italy, increasing from 5.5% in 1993 to 7.7% in 1996. In an attempt to obtain some insights into the situation in Italy, 39 penicillin-resistant Italian isolates identified among the approximately 700 S. pneumoniae strains collected from 1993 to 1996 from nine different centers in central and northern Italy (Milan, Bergamo, Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Parma, Perugia, Turin, and Vercelli) were examined by microbiological and molecular techniques. Our findings, as described in this communication, indicate that more than half of the penicillin-resistant isolates in this collection were members of two internationally widespread pneumococcal clones that were most likely imported into Italy. In addition, properties of a unique and novel multidrug-resistant “Italian” clone are also described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Thirty-nine S. pneumoniae isolates selected for their penicillin resistance from about 700 strains recovered from 1993 to 1996 from nine different centers in central and northern Italy (Milan, Bergamo, Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Parma, Perugia, Turin, and Vercelli) were studied. The isolation dates, geographic origins, and clinical sources (when available) of the strains are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of S. pneumoniae isolates recovered in Italy

| Strain code | Isolation date (mo/yr) | Source | Geographic origin | Serotype | Clonal type (PFGE pattern) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN 1R | 2/93 | Sputum | Bergamo | 23 | A |

| GEN 2R | 4/93 | Pharyngeal swab | Bologna | 23 | A1 |

| GEN 3R | 5/93 | Pharyngeal swab | Bologna | 23 | A |

| GEN 4R | 12/93 | Blood | Parma | 23 | A |

| GEN 5Ra | 12/93 | NAb | Bologna | 23 | C |

| GEN 6Ra | 6/94 | Pharyngeal swab | Parma | 23 | C |

| GEN 7Ra | 6/94 | Sputum | Bologna | 23 | C |

| GEN 8Ra | 6/94 | Sputum | Bologna | 23 | C |

| GEN 9Ra | 9/95 | Nose | Parma | 23 | C |

| GEN 10Ra | 11/95 | Eye | Genoa | 23 | C |

| GEN 11R | 11/95 | NA | Vercelli | 19 | A2 |

| GEN 12R | 11/95 | Sputum | Genoa | 19 | A2 |

| GEN 13Ra | 5/95 | Nose | Parma | 23 | C |

| GEN 14Ra | 5/95 | Nose | Parma | 23 | C |

| GEN 15R | 3/96 | Nose | Vercelli | 9 | B |

| GEN 16R | 10/96 | NA | Vercelli | 19 | A2 |

| GEN 17R | 12/96 | NA | Turin | 23 | A1 |

| GEN 1I | 2/93 | NA | Bergamo | 23 | D |

| GEN 2I | 4/93 | Pus | Bergamo | 23 | D |

| GEN 3I | 5/93 | Sputum | Perugia | 9 | B4 |

| GEN 4I | 5/93 | Blood | Turin | 19 | A3 |

| GEN 5I | 12/93 | NA | Genoa | 19 | A3 |

| GEN 6I | 12/93 | NA | Genoa | 19 | A3 |

| GEN 7I | 5/94 | Nose | Genoa | 19 | A3 |

| GEN 8I | 6/94 | Sputum | Parma | 19 | B |

| GEN 9I | 6/94 | Nose | Parma | 9 | B3 |

| GEN 12I | 6/95 | Sputum | Parma | 21 | Unique |

| GEN 13I | 11/95 | NA | Vercelli | 9 | C |

| GEN 14I | 11/95 | Skin | Vercelli | 9 | C |

| GEN 15I | 4/96 | Sputum | Vercelli | 9 | C |

| GEN 16I | 5/96 | Sputum | Vercelli | 9 | C |

| GEN 17I | 9/96 | Pharyngeal swab | Genoa | 23 | A |

| GEN 18I | 9/96 | NA | Genoa | 23 | A |

| GEN 19I | 10/96 | NA | Vercelli | 15 | Unique |

| GEN 20I | 10/96 | NA | Genoa | 23 | Unique |

| GEN 21I | 11/96 | Sputum | Genoa | 9 | B4 |

| GEN 22I | 12/96 | NA | Vercelli | 19 | A4 |

| GEN 24I | 11/96 | Pharyngeal swab | Genoa | 9 | B2 |

| GEN 25I | 11/96 | Sputum | Genoa | 9 | B2 |

Isolate belonging to Italian clone.

NA, not available.

Biochemical characterization, serotyping, and susceptibility testing.

Isolates were identified as S. pneumoniae by their susceptibility to optochin, their solubility in bile (23), and by employing the API system (Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Serotypes were determined on the basis of capsular swelling after suspension in antisera (Dako Co.).

The susceptibility of the pneumococcal strains to antimicrobial agents was assessed by a microdilution assay in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with 5% lysed horse blood, as detailed in guidelines from the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (24). MICs were determined after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was included in each run as a control.

The antimicrobial agents tested (penicillin G, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and tetracycline) were obtained from commercial sources.

Strains were defined as antibiotic susceptible, intermediately resistant, or resistant in accordance with NCCLS guidelines (24).

PFGE.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) were performed by methods described previously (30). A CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) was used for running the gels. Running conditions were as follows: 23 h at 14°C at a voltage of 200 V ramped with an initial forward time of 1 s and a final forward time of 30 s. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed.

Hybridization with DNA probes.

Gels to be hybridized were transferred to nylon membranes with the Vacuum Gene System (Pharmacia Biotech). The resulting membranes were probed with the ECL system (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. The molecular weights of the hybridization signals and the corresponding SmaI fragments were determined by comparison with a molecular weight ladder.

Probes.

DNA probes for ermB and mefE genes were obtained through PCR with, as templates, S. pneumoniae 02J 1095 (for ermB) and 02J 1175 (for mefE) and primers GAAAARGTACTAACCAAATA and AGTAAYGGTACTTAAATTGTTTAC (for ermB) and AGTATCATTAATCACTAGTGC and CGTAATAGATGCAATCACAGC (for mefE), generated on the basis of sequences published by Sutcliffe et al. (31).

It has been previously shown that streptococcal isolates carry chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) genes belonging to both catpC194 and catpC221 classes (7, 33). To design primers, protein sequences of the CAT determinants belonging to both classes (sequences under accession no. V01277, J01754, K01998, X65462, S50737, X60827, S45036, X02529, and X02872) were aligned and primers were designed to the conserved regions. The pair of primers thus obtained, CATd (TTAGGYTATTGGGATAAGTTA)-CATr (CATGRTAACCATCACAWACAG), was used to amplify a 338-bp fragment internal to the cat gene (235 to 572 bp of the coding region of the cat gene of plasmid pC164). To generate the probe, template DNA from strain 8249 was prepared as described previously (25) and utilized in a PCR in which annealing was performed at 47°C for 30 s and extension was done at 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles. Primers used to generate the tetM probe were TETMd (TGGAATTGATTTATCAACGG) and TETMr (TTCCAACCATACAATCCTTG); they were designed to amplify a 1,080-bp region internal to the tetM (34) gene corresponding to nucleotides 529 to 1608 of the sequence under accession no. X52632. Preparation of the template and strain used were the same as for preparation of the CAT probe. PCR was performed with annealing at 50°C for 30 s followed by extension at 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles. Purification and labeling of the probes were done as described before (20, 25).

Labeling and titration of PBPs.

Penicillin-binding protein (PBP) profiles and penicillin affinity were determined as described previously (22).

Preparation of chromosomal DNA and fingerprinting of the PBP 1A, 2B, and 2X genes.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared as described by Dowson et al. (9). The PBP 2B and 2X genes were amplified as 1.5- and 2-kb fragments, respectively, by PCR, as described by Dowson et al. (9) and Munoz et al. (21). The PBP 1A gene was amplified as a 2-kb fragment by PCR by using the oligonucleotides PN1A up (dACTAGTTGCAACAACTTCTAG) and PN1A down (dTTGAACTTCTGATGAGG) and the same PCR conditions used for PBP 2B and 2X. The amplification products (20 μl each) were purified by using the Wizard PCR purification system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions and were digested by restriction endonucleases HinfI (PBP 1A), StyI (PBP 2B), and MseI plus DdeI (PBP 2X) and separated by electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose gels, as described by Hermans et al. (14).

RESULTS

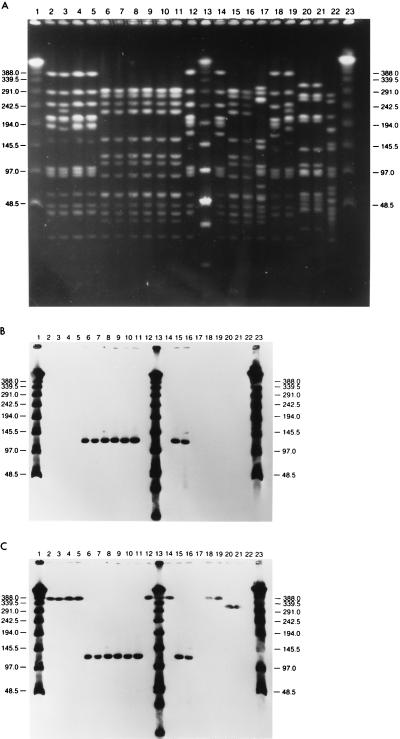

Tables 1 and 2 summarize relevant characteristics of the 39 S. pneumoniae clinical isolates examined, including isolation date, serotype, source (when available), geographic origin, assignment to PFGE pattern, and antibiotic resistance level, as well as results of hybridization with different DNA probes. Figure 1A through C show PFGE profiles of chromosomal DNA as well as hybridization patterns with DNA probes for erythromycin and tetracycline resistance genes from a representative group of strains.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic resistance patterns and hybridization of S. pneumoniae penicillin-resistant isolates recovered in Italy with ermB, mefE, tetM, and cat probes

| Strain code | MIC (mg/liter) ofa:

|

Hybridization with resistance probesb

|

Chromosomal location (PFGE SmaI band) (kb)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | ERY | CHL | TET | CO-TX | ermB | mefE | cat | tetM | ermB | mefE | cat | tetM | |

| GEN 1R | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | 2 | 16 | − | − | + | + | 388 | |||

| GEN 2R | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | 2 | 16 | − | − | + | + | 388 | |||

| GEN 3R | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | 2 | 8 | − | − | + | + | 388 | |||

| GEN 4R | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | 4 | 16 | − | − | + | + | 388 | |||

| GEN 5Rc | 4 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 6Rc | 4 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 7Rc | 2 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 8Rc | 4 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 9Rc | 2 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 10Rc | 2 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 11R | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | − | + | + | + | 388 | 388 | ||

| GEN 12R | 2 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 8 | − | + | + | + | 388 | 388 | ||

| GEN 13Rc | 4 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 14Rc | 4 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 8 | + | − | − | + | 122 | |||

| GEN 15R | 2 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 16R | 2 | 8 | 8 | 32 | 8 | − | + | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 17R | 2 | 0.12 | 8 | 2 | 2 | − | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | ||

| GEN 1I | 0.25 | 0.12 | 16 | 16 | 0.5 | − | − | + | + | 295 | 295 | ||

| GEN 2I | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 1 | − | − | + | + | 295 | 295 | ||

| GEN 3I | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 4 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 4I | 1 | >128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 5I | 1 | 128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 6I | 1 | 128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 7I | 1 | 128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 8I | 0.12 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.12 | 1 | − | − | + | − | 388 | 388 | ||

| GEN 9I | 1 | >128 | 2 | 32 | 4 | + | − | − | + | 388 | 388 | ||

| GEN 12I | 0.12 | >128 | 16 | 32 | 0.5 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 13I | 0.25 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 14I | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 1 | 4 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 15I | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 4 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 16I | 0.12 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 17I | 1 | >128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 18I | 1 | >128 | 16 | 16 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 388 | 388 | 388 | |

| GEN 19I | 0.12 | 32 | 2 | 16 | 0.25 | + | − | − | + | 332 | 332 | ||

| GEN 20I | 0.12 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 8 | − | − | − | − | ||||

| GEN 21I | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 4 | − | − | − | + | ||||

| GEN 22I | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 2 | − | + | + | + | 338 | 338 | 338 | |

| GEN 24I | 1 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.12 | 2 | − | − | − | + | 338 | |||

| GEN 25I | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | − | − | − | + | 338 | |||

PEN, penicillin; ERY, erythromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; TET, tetracycline; CO-TX, co-trimoxazole.

Symbols: +, hybridization positive; −, hybridization negative.

Isolate belonging to Italian clone.

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of penicillin-resistant pneumococcal isolates for which penicillin MICs were 2 μg/ml or higher. (A) PFGE types of all major clones recovered in Italy; (B and C) results of hybridization of the same gels as those in panel A with the ermB and tetM probes, respectively. Lanes 1, 13, and 23, molecular weight standards; lanes 2 to 5, strains GEN 1R, GEN 2R, GEN 3R, and GEN 4R, Italian isolates indistinguishable from the capsular type 23F Spanish/USA clone; lanes 6 to 11, strains GEN 5R, GEN 6R, GEN 7R, GEN 8R, GEN 9R, and GEN 10R, capsular type 23F Italian clone isolates; lanes 12 and 14, GEN 11R and GEN 12R, capsular type 19 in vivo capsular transformants of the Spanish/USA clone; lanes 15 and 16, GEN 13R and GEN 14R, more isolates of the Italian clone; lane 17, FEM 15R, representative of the cluster of Italian isolates indistinguishable from the capsular type 9 French/Spanish clone; lanes 18 and 19, GEN 16R and GEN 17R, Italian representatives of the Spanish/USA clone (GEN 16R is an apparent in vivo capsular transformant to capsular type 19) and GEN 17R is a capsular type 23F isolate); lanes 20 and 21, GEN 1-I and 2-I, capsular type 23 strains for which penicillin MICs were intermediate and which had a unique PFGE type; lane 22, GEN 3-I, capsular type 9 isolate with PFGE type of the French/Spanish clone but with low-level penicillin resistance. Molecular sizes of standards, in kilobases, are shown to the left and right of the gels.

Of the 39 strains studied, 22 were intermediately resistant to penicillin (MICs, 0.1 to 1 mg/liter) and 17 were highly resistant (MIC range, 2 to 4 mg/liter) according to the NCCLS breakpoints. Moreover, 53.8, 41, 61.5, and 89.7% of the strains were resistant to erythromycin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and co-trimoxazole, respectively.

Isolates for which penicillin MICs were ≥1 mg/liter (30 of 39) tended to be more frequently resistant to at least two other antibiotics and showed less variable backgrounds in terms of PFGE patterns and serotypes than isolates for which penicillin MICs were <1 mg/liter (9 of 39). In particular, 23 S. pneumoniae isolates belonging to the first group of 30 strains were resistant to two or more additional drugs (erythromycin, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and/or tetracycline).

Only three different serotypes (serotypes 23, 9, and 19) and three main PFGE profiles (named, arbitrarily, A, B, and C) were found among the 30 strains; 15 of these 30 strains expressed serotype 23F, and about half of these (7 of 15) showed the PFGE profile characteristic of the widespread Spanish/USA international clone or closely related variants. The remaining eight S. pneumoniae isolates, which had the 23F serotype, for which the penicillin MICs were high, and which were resistant to tetracycline, co-trimoxazole, and erythromycin, showed a novel PFGE pattern which may represent the emergence of a unique Italian multidrug-resistant clone. Seven of 30 isolates belonging to serotype 19 had a PFGE profile very similar to that of the Spanish/USA serotype 23 clone, suggesting that these bacteria may be the products of a capsular transformation event from serotype 23F to serotype 19.

All eight isolates expressing serotype 9 had a PFGE profile characteristic of a second widely dispersed (French/Spanish) international clone and its PFGE subtype variants (4, 10). The nine penicillin-resistant strains for which the MICs were <1 mg/liter displayed more variable backgrounds (six different PFGE patterns and four serotypes, i.e., 23, 19, 9, and 21).

The results of hybridization with probes for ermB, mefE, tetM, and cat genes are summarized in Table 2. All strains with high-level erythromycin resistance (MIC range, 32 to >128 mg/liter) hybridized with the ermB probe, while all strains with low-level resistance (MIC, 4 to 16 mg/liter) hybridized with the mefE probe as expected (32). Southern hybridization of chromosomal SmaI digests located the ermB hybridizing signal to a DNA band of 388 kb in 8 of the 17 highly erythromycin-resistant isolates, to a 322-kb band in 1 isolate, and to a 122-kb band in the remaining 8 isolates. The mefE gene probe hybridized with a 388-kb DNA band in three strains and in the 338-kb band in one strain.

A good correlation between hybridization and resistance level was also found for chloramphenicol resistance; although three strains defined as susceptible according to NCCLS breakpoints (MICs, 4 mg/liter) also hybridized with the cat probe (Table 2), the significance of this is not clear at the present time.

All tetracycline-resistant strains and seven tetracycline-susceptible strains (four of which showed borderline resistance) gave a positive hybridization signal with the tetM probe. Multidrug-resistant strains carried the erythromycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol resistance genes on the same DNA band in SmaI digests of chromosomal DNA.

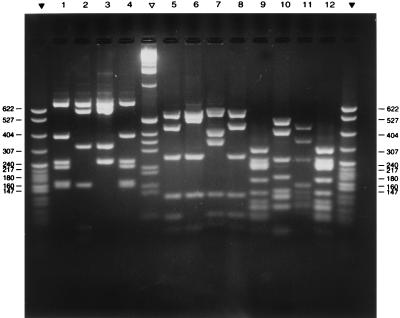

Fluorographic assays with radioactive penicillin showed, as expected, that the high-molecular-weight PBPs of all penicillin-resistant isolates had a reduced affinity for penicillin (22). The PBP 1A, 2X, and 2B genes amplified from the penicillin-susceptible laboratory strain R6, two representatives of the international Spanish/USA clone (one with serotype 23F and the other with serotype 19), and a representative of the serotype 23F Italian clone were compared for their RFLP patterns by using a set of restriction enzymes. Each of these PBP genes yielded unique and distinct DNA fingerprints, including the two representatives of the Spanish/USA clone which had an RFLP pattern in common (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

RFLP patterns of PCR-amplified PBP genes of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates from Italy. Lanes 1 to 4, HinfI digests of PBP 1A; lanes 5 to 8, StyI digests of PBP 2b; lanes 9 to 12, MseI-plus-DdeI digests of PBP 2x. Sources of the amplified genes: strain GEN R1, (lanes 1, 5, and 9), strain R6 (susceptible laboratory control) (lanes 2, 6, and 10); strain GEN 7R (lanes 3, 7, and 11), and strain GEN11R (lanes 4, 8, and 12). Leftmost and rightmost lanes and the lane between lanes 4 and 5 contain the molecular weight marker pBR322 SpI digest (▾) and the 1-kb marker (▿) (Promega). Molecular sizes of standards, in kilobases, are shown to the right and left of the figure.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to other European and western Mediterranean countries, such as France, Spain, and Portugal (2–4, 8, 11, 12, 16, 17, 22, 35), the frequency of penicillin-resistant pneumococci has remained relatively low in Italy, closer to the rates reported from Germany (26, 27, 29), the United Kingdom (15), and The Netherlands (14). In an attempt to obtain some insights into the nature of these relatively rare penicillin-resistant pneumococci in Italy, we examined 39 resistant strains recovered from about 700 pneumococcal isolates collected between 1993 and 1996 in central and northern Italy. This study represents the first detailed analysis of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae strains circulating in Italy.

Of the 39 isolates analyzed, 22 had intermediate-level penicillin resistance, based on the current clinical microbiology definition of breakpoints, and 17 had high-level penicillin resistance. Nevertheless, the MICs for most strains (25 of 39) were near to or higher than the resistance breakpoint (1 to 2 mg/liter). The overwhelming majority of the penicillin-resistant Italian isolates expressed three serogroups or serotypes: 23, 9, and 19 (represented by 18, 10, and 9 strains, respectively). These could be grouped into three major PFGE types (labeled A, B, and C), and these strains frequently carried resistance genes to erythromycin (53.8%), chloramphenicol (41%), tetracycline (61.5%), and co-trimoxazole (89.7%).

All highly erythromycin-resistant strains carried the ermB gene, while strains with low-level resistance carried the mefE gene, as expected (32). In multidrug-resistant strains exhibiting resistance to erythromycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol, genetic determinants for these resistance factors were invariably located on the same DNA fragment in SmaI hydrolysates. Although tetM and ermB are carried on transposon Tn1545 (6), the cat and mef genes are not usually part of this transposable element. The colocalization of these genes on the same SmaI fragment may be fortuitous. Interestingly, three fully tetracycline-susceptible isolates gave a strong hybridization signal with the tetM DNA probe; the mechanism of suppression of the tetracycline resistance phenotype in these bacteria is currently under investigation.

The causes of the relatively low incidence of penicillin-resistant pneumococci in Italy are not known. It is conceivable that the low prevalence is related to the local drug prescription habits (13): Italy is the only country in Europe where over 80% of antibiotic courses are given parenterally, and the most frequently used drugs include expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, such as cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. This mode of antibiotic usage is dominant both in the hospital and in the community setting. It may be speculated that the relatively low prevalence of resistant pneumococci may be related to the higher rates of eradication of these respiratory pathogens due to the aggressive parenteral therapy. Expanded-spectrum cephalosporins are intrinsically more active against S. pneumoniae than penicillin derivatives and, thus, are less prone to produce subinhibitory concentrations conducive to selection of resistant strains, unlike drugs administered through oral therapy.

Analysis of the DNA fingerprints revealed that a large proportion (22 of 30, or 73%) of the penicillin-resistant bacteria for which MICs were ≥1.0 μg/ml were representatives of two internationally widespread multidrug-resistant clones: the 23F Spanish/USA clone, already identified in several countries on five continents, and the serotype 9 or 14 French/Spanish clone, spread to western European and South American countries. The surprisingly high-level representation of these two widespread penicillin-resistant clones among the Italian isolates further documents their remarkable epidemicity, the microbiological or mechanistic basis of which is currently not understood. Closer analysis by DNA fingerprinting techniques suggests that the group of the penicillin-resistant Italian isolates expressing serotype 19 was, most likely, the product of a capsular transformation event in which the recipient was a 23F Spanish/USA clonal isolate. Similar observations have already been described in recent reports (1, 5, 25).

The microbiological, serological, and molecular analyses also identified among the Italian isolates a hitherto undescribed multidrug-resistant clone of S. pneumoniae that appears to be unique to Italy. This Italian clone expresses serotype 23F, has a high level of penicillin resistance, is resistant to erythromycin, tetracycline, and co-trimoxazole, and exhibits a unique PFGE type and unique RFLP patterns for the PBP genes 1A, 2X, and 2B. This Italian clone was first detected in the 1993 sample, i.e., during the year when the Italian surveillance was initiated. This Italian clone was identified only in the strain collections originating in three of the nine collaborating centers (Bologna, Vercelli, and Parma), while the representatives of the two international clones appeared to be uniformly distributed among all nine collection centers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Partial support for these investigations was provided by a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service (NIH RO1 AI37275). M. Ramirez was supported by a fellowship from the Gulbenkian Foundation and Fundação Luso Americano para o Desenvolvimento. A. Marchese was supported by a fellowship from the University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes D M, Whittier S, Gilligan P H, Soares S, Tomasz A, Henderson F W. Transmission of multidrug-resistant serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae in group day care: evidence suggesting capsular transformation of the resistant strain in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:890–896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedos J P, Chevret S, Chastang C, Geslin P, Reginer R The French Cooperative Pneumococcus Study Group. Epidemiological features of and risk factors for infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains with diminished susceptibility to penicillin: findings of a French survey. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:63–72. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho C, Geslin P, Vaz Pato M V. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in France and Portugal. Pathol Biol. 1996;44:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey T J, Berrón S, Daniels M, Garcia-Leoni M E, Cercenado E, Bouza E, Fenoll A, Spratt B G. Multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from Spanish hospitals (1988–1994): novel major clones of serotypes 14, 19F and 15F. Microbiology. 1996;142:2747–2757. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Zhou J, Martin C, Spratt B G, Musser J M. Horizontal transfer of multiple penicillin-binding protein genes, and capsular biosynthetic genes, in natural populations of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2255–2260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courvalin P, Carlier C. Transposable multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:291–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00430441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David F, de Cespedes G, Delbos F, Horaud T. Diversity of chromosomal genetic elements and gene identification in antibiotic-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus bovis. Plasmid. 1993;29:147–153. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doit C, Denamur E, Picard B, Geslin P, Elion J, Bingen E. Mechanisms of spread of penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae strains causing meningitis in children in France. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:520–528. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Spratt B G. Extensive remodelling of the transpeptidase domain of penicillin-binding protein 2B of a penicillin-resistant South African isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasc A M, Geslin P, Sicard A M. Relatedness of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 9 strains from France and Spain. Microbiology. 1995;141:623–627. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-3-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein, F. W., J. F. Acar, and The Alexander Project Collaborative Group. 1996. Antimicrobial resistance among lower respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: results of the 1992–93 Western Europe and USA collaborative surveillance study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38(Suppl. A):71–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gomez J, Ruiz-Gomez J, Hernandez-Cardona J L, Nunez M L, Canteras M, Valdes M. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis: a prospective study in Murcia, Spain, 1983–1992. Chemotherapy. 1994;40:299–303. doi: 10.1159/000239210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halls G A. The management of infections and antibiotic therapy: an European survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:985–1000. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans P W M, Sluijter M, Elzenaar K, van Veen A, Schonkeren J J M, Nooren F M, van Leeuwen W J, de Neeling A J, van Klingeren B, Verbrugh H A, de Groot R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in The Netherlands: results of a 1-year molecular epidemiologic survey. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1413–1422. doi: 10.1086/516474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson A P, Speller D C E, George R C, Warner M, Dominigue G, Efstration A. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance and serotypes in pneumococci in England and Wales: results of observational surveys in 1990 and 1995. Br Med J. 1996;312:1454–1456. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7044.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefevre J C, Bertrand M A, Fauçon G. Molecular analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae from Toulouse, France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF02113426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefevre J C, Gasc A M, Lemozy J, Sicard A M, Fauçon G. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis for molecular epidemiology of penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. Pathol Biol. 1994;42:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchese A, Debbia E A, Arvigo A, Pesce A, Schito G C. Susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in Italy to penicillin and ten other antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:833–837. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchese, A., E. A. Debbia, A. Pesce, and G. C. Schito. Comparative activity of amoxicillin and ten other oral drugs against penicillin susceptible and resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains recently isolated in Italy. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.McDougal L K, Facklam R, Reeves M, Hunter S, Swenson J M, Hill B C, Tenover F C. Analysis of multiply antimicrobial-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2176–2184. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. Intercontinental spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marton A, Parkinson A J, Sorensen U, Tomasz A. Geographic distribution of penicillin resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin binding protein profile, surface protein A typing and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nesin M, Ramirez M, Tomasz A. Capsular transformation of a multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:707–713. doi: 10.1086/514242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichmann P, Varon E, Gunther E, Reinert R R, Luttikens R, Marton A, Geslin P, Wagner J, Hakenbeck R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Germany: genetic relationship to clones from other European countries. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:377–385. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-5-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinert R R, Queck A, Kaufhold A, Kresken M, Luttikens R. Antimicrobial resistance and type distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates causing systemic infections in Germany, 1992–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1398–1401. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schito, G. C., S. Mannelli, A. Pesce, and The Alexander Project Group. 1997. Trends in the activity of the macrolide and β-lactam antibiotics and resistance development. J. Chemother. 9(Suppl. 3):18–28. [PubMed]

- 29.Sibold C, Wang J, Henrichsen J, Hakenbeck R. Genetic relationships of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated on different continents. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4119–4126. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4119-4126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares S, Kristinsson K G, Musser J M, Tomasz A. Evidence for the introduction of a multiresistant clone of serotype 6B Streptococcus pneumoniae from Spain to Iceland in the late 1980s. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:158–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrak L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutcliffe J, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes resistant to macrolides but sensitive to clindamycin: a common resistance pattern mediated by an efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1817–1824. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trieu-Cuot P, de Cespedes G, Bentorcha F, Delbos F, Gaspar E, Horaud T. Study of heterogeneity of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) genes in streptococci and enterococci by polymerase chain reaction: characterization of a new CAT determinant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2593–2598. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trieu-Cuot P, Poyart-Salmeron C, Carlier C, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence of the erythromycin resistance gene of the conjugative transposon Tn1545. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3660. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaz Pato M V, de Carvalho C B, Tomasz A The Multicenter Study Group. Antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Portugal. A multicenter study between 1989 and 1993. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:59–69. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]