Abstract

Policy Points.

Cultural racism—or the widespread values that privilege and protect Whiteness and White social and economic power—permeates all levels of society, uplifts other dimensions of racism, and contributes to health inequities.

Overt forms of racism, such as racial hate crimes, represent only the “tip of the iceberg,” whereas structural and institutional racism represent its base. This paper advances cultural racism as the “water surrounding the iceberg,” allowing it to float while obscuring its base.

Considering the fundamental role of cultural racism is needed to advance health equity.

Context

Cultural racism is a pervasive social toxin that surrounds all other dimensions of racism to produce and maintain racial health inequities. Yet, cultural racism has received relatively little attention in the public health literature. The purpose of this paper is to 1) provide public health researchers and policymakers with a clearer understanding of what cultural racism is, 2) provide an understanding of how it operates in conjunction with the other dimensions of racism to produce health inequities, and 3) offer directions for future research and interventions on cultural racism.

Methods

We conducted a nonsystematic, multidisciplinary review of theory and empirical evidence that conceptualizes, measures, and documents the consequences of cultural racism for social and health inequities.

Findings

Cultural racism can be defined as a culture of White supremacy, which values, protects, and normalizes Whiteness and White social and economic power. This ideological system operates at the level of our shared social consciousness and is expressed in the language, symbols, and media representations of dominant society. Cultural racism surrounds and bolsters structural, institutional, personally mediated, and internalized racism, undermining health through material, cognitive/affective, biologic, and behavioral mechanisms across the life course.

Conclusions

More time, research, and funding is needed to advance measurement, elucidate mechanisms, and develop evidence‐based policy interventions to reduce cultural racism and promote health equity.

Keywords: racism, social determinants of health, health disparity, culture, fundamental causes

“…when habitus encounters a social world of which it is the product, it is like a fish in water: it does not feel the weight of the water and it takes the world about itself for granted…It is because this world has produced me, because it has produced the categories of thought that I apply to it, that it appears to me as self‐evident.”

—Pierre Bourdieu, An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology 1 p127

Racism, a “fundamental cause” of health inequities, 2 operates across internalized, personally mediated, institutional, structural, and cultural dimensions. In recent decades, personally mediated racism, or racial discrimination enacted among individuals, has been a dominant focus of the study of racism and health. Although a large body of literature has found robust associations between experiences of racial discrimination and adverse health outcomes among racially marginalized groups, these experiences only represent the “tip of the iceberg.” 34 p131 As described previously, structural and institutional forms of racism comprise the base of the iceberg, operating beneath the surface to shape the distribution of societal risk and protective factors, ultimately determining patterns of health and well‐being by race. 3 , 4

There is considerable interest in moving the conversation “under the surface” to more explicitly interrogate the fundamental role of structural racism in the production of health inequities. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 This recent trend is evidenced by several comprehensive review papers, 9 , 10 measurement advances, 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 and calls for funding research on structural racism and health. 17 This fast‐growing body of research has demonstrated the widespread consequences of structural racism for health inequities, expanding the evidence base needed to inform structural interventions, such as policy reform at both the societal and institutional levels. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22

This important research notwithstanding, the increasing focus in the health literature on the more fundamental dimensions of racism has largely neglected cultural racism. Within the United States and other European‐colonized societies, cultural racism refers to a culture of White supremacy—the pervasive ideological system that values, protects, and normalizes Whiteness and White power. 23 Cultural racism operates within our shared social consciousness and is made visible in our cultural expressions, including the language, symbols, and media of dominant society. Returning to the iceberg analogy, we conceptualize cultural racism as the water surrounding the iceberg, allowing it to float. Numerous authors have used the water metaphor to discuss racism, but here, we apply it specifically to cultural racism. 3 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 As the water, cultural racism buttresses the other dimensions of racism in the production of social and health inequities. Simultaneously, cultural racism rationalizes, naturalizes, and obscures structural racism, as the murky (i.e., “darkly vague or obscure” 31 ) water surrounding the iceberg renders its base invisible. Importantly, the iceberg and the water that surrounds it are of the same substance in different states, just as each form of racism represents a different dimension of the same system.

Several scholars have defined cultural racism and its role in producing health inequities, 3 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 and a recent systematic review found evidence of associations between area‐level racial prejudice—a measure of cultural racism—and various adverse health outcomes. 35 However, beyond this small body of literature, empirical research explicitly operationalizing cultural racism and examining associations with health outcomes is sparse.

The purpose of this paper is to 1) provide public health researchers with a clearer understanding of what cultural racism is, 2) provide understanding of how it operates in conjunction with the other dimensions of racism to produce health inequities, and 3) offer directions for future research.

Defining Cultural Racism

Broadly speaking, a society's culture can be defined as its “values and belief system,” which are rooted in history, dynamic over time and place, and passed to subsequent generations through social learning. 36 p 52 These values are reflected in the language, symbols, and mass media of society and shape meaning and decision making among individuals, groups, and institutions. 18 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 Although a society may have multiple cultures operating in parallel, the focus of the present discussion is on the dominant culture—rooted in the values and interests of those in power (i.e., hegemonic), 38 , 39 which, in the context of the United States and other European‐colonized countries, reflects the values and interests of White people.

Cultural racism can therefore be understood as 1) values and belief systems of White superiority that 2) operate at the level of our shared social consciousness and are 3) expressed in the language, symbols, and media representations of dominant society. 18 , 20 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 40 , 41 We briefly describe these three dimensions of cultural racism below (see Appendix 1 for more details).

Values and Belief Systems of White Superiority

Cultural racism is an ideology of White supremacy that is historically rooted in the interests of the White people, permeates all levels of society, and maintains social and economic power relations. 18 , 36 , 40 , 42 Alang and colleagues define White supremacy as “the glossary of conditions, practices, and ideologies that underscore the hegemony of Whiteness and White political, social, cultural, and economic domination.” 23 p815 A culture of White supremacy covets “Whiteness as property”43—something to be safeguarded—which forms the basis of White racial privilege and associated material benefits. Relatedly, Corces‐Zimmerman and colleagues describe the concept of “ontological expansiveness,” or how “Whiteness as a structuring ideology in U.S. society permits White people to think, act, and interact with the space around them in such a way that they have the right to inhabit any space, be it material or otherwise.” 44 p432 These ideologies of entitlement are core to cultural racism and White supremacy, underpinning centuries of imperialism and colonization, as well as their contemporary manifestations such as gentrification and cultural appropriation. 44 , 45

The ideology of White supremacy is created and maintained through cultural processes of racialization and stigmatization. 18 , 37 Racialization refers to how we define and delineate (i.e., “form” 46 ) racial and ethnic categories based on phenotypic markers, such as skin color, hair texture, and facial features as well as behaviors, tastes and preferences, family structure, occupation, income, and educational attainment, among other characteristics. Racial categories are socially constructed, fluid, and historically contingent but have grave consequences for individuals and groups based on their position in the racial hierarchy. 42 , 46 As Omi and Winant summarize, “[racial categories] may be arbitrary, but they are not meaningless.” 46 p111 Stigmatization refers to how these socially constructed racial groups undergo differential labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination, all within the context of a power structure. 47 , 48 The stigmatization of racial groups defined as not “White” forms the substance of cultural racism, which exists within our shared social consciousness and is manifest in various cultural expressions, as described in the following sections.

Shared Social Consciousness

As the water in which we swim, cultural racism “surrounds” 49 all members of society. 36 , 50 Values that uphold White supremacy, including stigmas and stereotypes, operate explicitly and implicitly in our collective consciousness, 50 , 51 or as Bourdieu describes, “the social order is progressively inscribed in people's minds.” 52 p473 These shared attitudes, biases, and prejudices about different racial groups pass through, and operate above, the minds of any one individual to comprise the broader “macropsychological construct” 53 p1034 we term collective racial prejudice and conceptualize as a dimension of cultural racism.

Another key feature of the shared social consciousness is the set of racial frames that guide how we collectively interpret information, assign meaning, and make decisions. 26 , 32 , 49 , 54 These frames offer a “mental model,” 55 p4 or blueprint for filling in the gaps of what we cannot see and for making assumptions about the “natural order of things.” 47 Two mutually constitutive racial frames that characterize and uphold cultural racism are the “White racial frame” 26 and the “frames of color‐blind racism” 54 p74 (herein, “color‐blind racial frame”). The White racial frame refers to the broad worldview that upholds Whiteness as the ideal and legitimizes the exploitation of people who are not White. 26 It is characterized by “a broad and persisting set of racial stereotypes, prejudices, ideologies, images, interpretations and narratives, emotions, and reactions to language accents, as well as racialized inclinations to discriminate.” 26 p3 The color‐blind racial frame is characterized by abstract notions of meritocracy, individualism, and equal opportunity (i.e., “abstract liberalism” 54 p74); attributing racial inequities to natural, biologic, or cultural differences; and the minimization of racism as a feature of the past and by implication, no longer relevant today. 54 Color‐blind racism upholds the White racial frame, and cultural racism more broadly, because it blames oppressed racial groups for their “race problem” 54 p1 rather than structural inequities that have privileged White people over other racial and ethnic groups. 54 These racial frames are hegemonic, meaning they represent ideologies and narratives constructed by the dominant group to maintain power but permeate all aspects of society and can be internalized by all members of society, including those from oppressed groups). 38 , 39 , 46

Cultural Expressions

The ideology of White supremacy is expressed in the language, symbols, and media of dominant society. These cultural expressions are how we can “see” and “hear” cultural racism.

Sociologists have long described ways in which language and symbols reflect cultural values and reinforce power relations. 56 Common terms like “White trash” and dog whistle terms such as “inner city” and “urban” simultaneously reflect and reinforce racial hierarchies and stereotypes. 57 , 58 Similarly, cultural images and symbols serve as overt or covert markers of White values and White superiority. Examples include confederate flags and monuments, stereotypic sports mascots (e.g., Kansas City Chiefs), and brand characters evoking imagery of Black servitude (e.g., Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben). 59 Linguistic and symbolic manifestations of cultural racism permeate multiple aspects of society, from science and technology to political discourse. 60

The media—including television, film, music, news, and online social media—serve as a primary conduit through which cultural racism is communicated to the public. 48 , 61 There are several key examples of cultural racism in the media. First, stigmatizing language and images are frequently used in news reporting 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 and advertising. 66 Second, stereotypical representations of Black and other racially marginalized groups are pervasive in television, film, music, and video games. 65 , 67 , 68 Third, cultural appropriation, or the adoption and sometimes commodification of one culture's practices or objects by a more dominant culture, 69 is often displayed in the media. 70 , 71 Last, in an increasingly digital world, social media have become a fertile home for cultural racism to flourish, exemplified through viral trends, Instagram filters, and digital objects such as GIFs. 70 , 72 , 73

How Cultural Racism Shapes Each Dimension of Racism to Harm Health

Cultural racism represents the ideological context that surrounds and upholds all other dimensions of racism. Cultural racism shapes health through material, environmental, behavioral, cognitive/affective, and biologic mechanisms across the life course. 20 , 34 , 74 Here, we briefly summarize the pathways through which racism shapes health inequities and then turn to a more detailed discussion of how cultural racism functions to sustain and amplify those processes. The relationships between cultural racism and each other dimension of racism are summarized in Appendix 2.

Racism and Health Overview

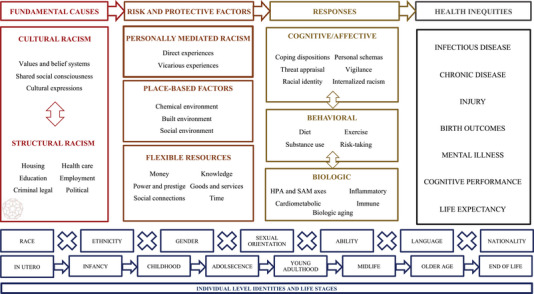

This conceptual model, adapted from Williams and Mohammed, 34 illustrates the pathways through which racism shapes health inequities Figure 1. This model is neither exhaustive nor definitive. Rather, it is meant to guide discussion and spark ongoing reflection, research questions and hypotheses, and analytic models intended to further explicate the impact of racism on health inequities.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Racism and Health [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Abbreviations: HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; SAM, sympathetic–adrenal–medullary.

The dimensions depicted in this figure are not exhaustive. For example, structural racism encompasses the involvement of the institutions depicted here and others not shown (e.g., banking). The boxes representing individuals’ identities and life stages illustrate individual‐level factors that may modify the effect of racism on health. They do not correspond to the orientation or sequencing of the columns above (fundamental causes, risk and protective factors, responses, and health inequities). The biologic responses box is characterized by accelerated dysregulation of these, and other, systems, a process referred to as “weathering.” 112 The Buckyball graphic is adapted from Gee and Hicken, 7 who used this image to illustrate the “inter‐institutional” connections that characterize structural racism.

Cultural and structural racism are displayed in the leftmost column to convey their role as “fundamental causes” of health, antecedent of the other dimensions of racism. 2 , 18 , 32 , 33 , 34 In this view, cultural and structural racism function as “risk regulators” 75 that determine the nonrandom distribution of societal risk and protective factors by socially constructed racial categories. 2 Although they operate at the same fundamental level, cultural and structural racism are mutually reinforcing; cultural values shape structural arrangements and vice versa. 33 , 76 The double‐headed arrow on Figure 1 illustrates the bidirectional relationship between cultural and structural racism, which we describe in more detail below.

Societal risk and protective factors, shaped by structural and cultural racism, are displayed in the second column of the model. One prominent risk factor is personally mediated racism, or racial prejudice and discrimination enacted among individuals. 19 The term “personally mediated” communicates the role of individual actors in facilitating the cultural and structural arrangements of society. 19 Personally mediated racism manifests in various ways—for example, overt versus covert, major versus everyday; 77 each of these manifestations can be experienced directly or vicariously. Vicarious racism occurs when one witnesses or hears about racial discrimination against a friend, family member, or members of one's racial group more broadly. 60 , 78 Studies have shown robust associations between experiences of racial discrimination—both direct and vicarious—and adverse health outcomes for marginalized racial groups. 20 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 Place‐based factors—shaped by cultural and structural racism—can be harmful or protective and encompass chemical (e.g., pollution), built (e.g., walkability), and/or social (e.g., community support) factors in the environments where we live, learn, and work. 86 , 87 , 88 Other protective factors include material (e.g., money, goods, and services) and neomaterial (e.g., knowledge, power, prestige, social connections, time) resources, 89 , 90 which can operate at the individual, group, or place level. 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 These resources are flexible, meaning they can be leveraged to improve health and well‐being across multiple outcomes. 2 , 97 Whereas Link and Phelan's original theory characterized certain flexible resources (specifically money, knowledge, power, prestige, and social connections) as fundamental causes of health, 97 , 98 their more recent theorizing positions racism as more fundamental than these resources, 2 as illustrated in Figure 1 above.

The third column depicts integrated cognitive/affective, behavioral, and biologic responses to racism and related risk factors. Psychosocial responses include threat appraisal and coping dispositions/schemas, racial identity, internalized racism, racism‐related vigilance, and anticipatory racism threat. 34 , 39 , 40 , 60 , 78 , 85 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 Behavioral responses include coping through food, substance use, risk‐taking, self‐neglect, impression management, and other forms of avoidance. 85 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 Biologic responses include activation of the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axes (which together comprise the body's primary stress response system); dysregulation of the inflammatory, immune, and cardiometabolic systems; telomere attrition; and sleep impairment, 84 , 85 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 with broad implications for chronic disease, healthy aging, and life expectancy. 112 , 116 , 117 Evidence suggests that racism‐related stress causes accelerated dysregulation of these, and other, systems, a process referred to as “weathering.” 112 The final column displays the primary categories of health outcomes for which there are vast inequities by race and demonstrated associations with racism within the literature.

Lastly, the bottom rows of Figure 1 incorporate individual‐level social identities and life stages. Intersectionality theory recognizes that racism interacts with capitalism, heteropatriarchy, and other systems of oppression at the societal level to shape individuals’ opportunities, life stressors, and ultimate health outcomes based on their multiple intersecting social identities. 21 , 121 , 122 The “X”s on the figure represent these intersections. Life course theories emphasize how factors occurring early in life, and accumulating across one's lifetime, shape health. 123 , 124 The arrows on the figure represent these pathways. Taken together, these rows encourage a consideration of how people may experience and embody racism differently based on their intersectional identities and stage in life. 21 , 85 , 89 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128

Cultural and Structural Racism

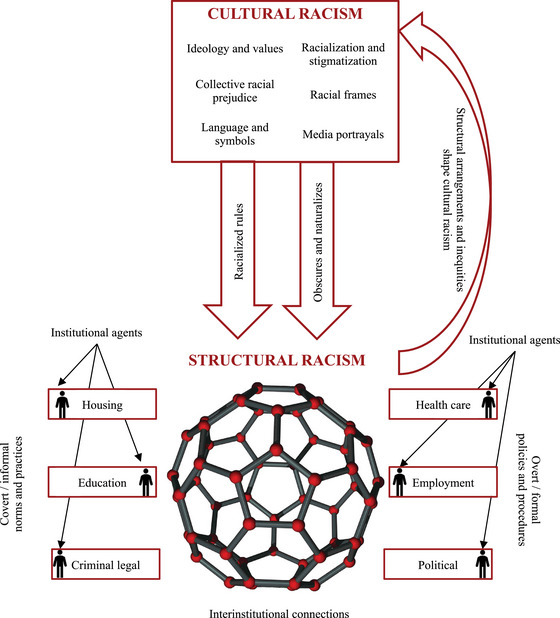

As with cultural racism, structural racism is a fundamental cause of health inequities. Structural racism involves the cooperation of multiple social institutions—including housing, health care, education, carceral, and banking, among others—to concentrate wealth, power, and ultimately health among White people relative to marginalized racial groups. 5 , 6 , 7 , 76 As illustrated in Figure 2 and described in the following sections, cultural and structural racism reinforce each other in several important ways.

Figure 2.

Cultural, Structural, and Institutional Racism [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The Buckyball graphic is adapted from Gee and Hicken, 7 who used this image to illustrate the “interinstitutional” connections that characterize structural racism. The cultural racism subdomains fall within the broader dimensions illustrated in Figure 1: “values and belief systems” encompasses “ideology and values” and “racialization and stigmatization,” “shared social consciousness” encompasses “collective racial prejudice” and “racial frames,” and “cultural expressions” encompasses “language and symbols” and “media portrayals.”

Cultural Racism Upholds Structural Racism

First, cultural racism upholds structural racism, or as Hicken and colleagues argue, “structural racism can be considered the actualization of cultural racism.” 18 This is because cultural values become materialized through interconnected institutional norms, policies, and practices. 18 , 32 , 33 , 34 Residential segregation and gentrification provide key examples of how White supremacist cultural values undergird racist structural processes.

Redlining, a historical example of structural racism involving the explicit cooperation of multiple institutions (e.g., government, banking, credit, and real estate 5 , 129 ) was rooted in cultural racism. Specifically, the cultural process of stigmatization—including labeling and status loss 48 —was visually represented on the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps and motivated the interinstitutional practice of physically separating Black from White residents through the provision of mortgages. 33 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 Once stigmatized groups have been physically segregated from dominant groups, discrimination can occur. 48 This is seen when the ideology of White superiority (and non‐White “disposability”) drives interinstitutional decision making around where to place toxin‐producing factories, highways, and other environmental hazards 36 in addition to isolation from a range of health‐promoting resources (e.g., healthy food, parks and recreation). 134

Gentrification is the process whereby wealthy White people reoccupy and “revitalize” previously segregated neighborhoods while displacing poor residents and residents of color. 135 Gentrification is rooted in values of White supremacy, including “Whiteness as property” 43 and “ontological expansiveness,” 44 which together provide White people with a sense of deservedness and entitlement to physically occupy all spaces. As Turan argues, “gentrification is a medium of Whiteness…[which allows]… White people eager to express White privilege and assert and reclaim their Whiteness.” 135 p76

There are several mechanisms through which cultural racism upholds structural racism. One mechanism is through cultural values shaping “racial rules” 136 or “racialized rules.” 7 First introduced by Flynn and colleagues 136 and further developed by Gee and Hicken, 7 racialized rules describe a set of norms that are “embedded in everyday practice across institutions, [and] serve to maintain the racial hierarchy while appearing neutral on their surface.” 7 These racialized rules directly reflect cultural values and racial frames. For example, the racialized rule of White as the referent category in quantitative research 7 reflects a White racial frame 26 , 54 and informs algorithms and decision making in medical, 137 , 138 legal, 139 banking, 140 and other institutions, with broad implications for health and well‐being. 141 , 142

The capitalization of racial groups is another racialized rule that warrants close consideration. As articulated by the Center for the Study of Social Policy, “to not name ‘White’ as a race is, in fact, an anti‐Black act which frames Whiteness as both neutral and the standard.” 143 We note here that the practice of capitalization (or not) is subject to change (as are the labels we use, such as “negro” versus “African American”). Grammatical conventions are simply another form of cultural representation, which are subject to racialization and the reinforcement of racist or anti‐racist practice.

Another mechanism connecting cultural to structural racism is policy regimes, or groupings of interrelated policies that reflect a common set of ideas and beliefs. 144 Social policies represent a key dimension of structural racism because they determine the allocation of resources across multiple institutions. 5 , 11 Collective beliefs about the origins of inequality, and whose lives are worth investing in and protecting, serve as the foundation for far‐reaching policy regimes in the United States. 18 , 33 , 36 , 145 For example, “abstract liberalism,” part of the color‐blind racial frame, implies that economic success can be attributed to hard work and intelligence, whereas failure can be attributed to laziness and lack of intelligence (i.e., the “myth of meritocracy”). 54 This manifestation of cultural racism undermines political will for reparative or egalitarian social policies, 146 , 147 , 148 thus upholding structural racism.

Cultural Racism Reflects Structural Racism

In parallel, material realities, policy regimes, and institutional arrangements shape our collective beliefs about the relative value of social groups. 33 , 76 For example, after same‐sex marriage was legalized, aggregate levels of antigay bias decreased, 149 suggesting that the policy shifted macrolevel social attitudes. Similarly, Payne and colleagues found that modern‐day levels of anti‐Black racial bias are geographically associated with historical slave ownership, demonstrating how historical forms of structural racism have long‐term impacts on our collective consciousness. 150 As previously noted, racial residential segregation reflects a historical culture of White supremacy. However, at the same time, by literally labeling neighborhoods of color as “dangerous,” the HOLC redlining maps shaped cultural beliefs about who makes a “good” or “safe” neighbor. 5 These examples underscore the bidirectional relationship between structural and cultural racism. 5 , 33

Cultural Racism Obscures and Naturalizes Structural Inequities

Third, as the murky water surrounding the iceberg, cultural racism obscures the role of structural racism in producing racial inequities in wealth and health. 18 , 32 , 33 This occurs at the level of our collective consciousness, 36 wherein the color‐blind racial frame causes us to attribute racial disparities to motivational, cultural, or biologic deficiencies of the individual or racial group rather than structural inequities. 54 As a result, inequities are legitimized and taken for granted as the “natural order of things.” 151 , 152 , 153 , 154

Concurrently, institutional arrangements, including those that produce and maintain racial inequities, are assumed to be neutral and commonsensical. 18 , 33 , 36 , 136 For example, the “myth of meritocracy” (part of the color‐blind racial frame) “obscures oppression by suggesting that racial disparities in hiring or school admissions are decided according to ‘objective’ standards applied equally to all.” 39 Relatedly, cultural processes of standardization and evaluation 37 shape practice across institutional settings (e.g., standardized tests for college admissions). These processes preserve inequities when they do not consider historical or contextual factors (e.g., differences in access to college preparation resources). 32 , 37 , 136

Finally, the “omission” of certain racial groups’ rights, experiences, histories, and identities is gaining more attention as a critical dimension of racism and driver of inequity. 134 , 155 Cultural racism likely perpetuates such omission, warranting further examination. For example, as an ideological system that values White lives above all others, cultural racism determines which populations and health issues should be prioritized in research and funding decisions. 33 , 155 When certain issues and inequities are deprioritized, they are easier to ignore because for many policymakers and citizens, “out of sight” means “out of mind.” Relatedly, cultural racism and other systems of power shape the production of knowledge, 156 including which and whose histories are told, omitted, 155 or “Whitewashed” in literature, film, and education, in turn shaping our collective imaginaries 32 about historical truth. 157 , 158

Cultural and Institutional Racism

Whereas structural racism describes racism operating across multiple institutions, institutional racism refers to racism occurring within specific institutional settings, such as schools, the workplace, the courts, and hospitals or health clinics. 19 , 33 We focus on two primary mechanisms through which cultural values and ideologies drive institutional racism: first, by shaping bias, prejudice, and behavior among people operating as agents of those institutions; and second, by influencing formal and informal policies and practices that govern how institutions operate.

Cultural Racism Guides Behavior Among Agents of Institutions

Cultural racism undergirds racial prejudice and discrimination enacted by institutional agents who serve as gatekeepers to societal resources needed to promote health and well‐being, such as teachers, physicians, police officers, and mortgage lenders, among others. 34 , 145 , 159 , 160 Figure 2 illustrates how these agents are situated within each social institution.

For example, cultural racism may shape racism in education. Cultural stereotypes about racially minoritized boys and men as more aggressive, dangerous, and deviant 161 , 162 are reflected in political discourse (e.g., Clinton referring to Black youth as “superpredators,” 57 , 163 Trump referring to Mexican immigrants as rapists and “bad hombres” 164 ) and media representations (e.g., the reality television show “Cops” 165 ), among other cultural expressions. 161 These stereotypes shape teachers’ perceptions of Black and other racially marginalized students as more deviant than White students, 161 , 162 , 166 , 167 , 168 , 169 leading to disproportionate, frequent, and punitive discipline. 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 Such racial inequities in school discipline represents a pervasive form of institutional racism, resulting in schools as a site of toxic stress and the early criminalization of Black male youth, with far‐reaching social, economic, and health consequences across the life course. 138 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179

Within the health care system, Black and Latine patients often receive delayed and/or poorer treatment compared with their White counterparts, 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 a salient example of racial discrimination via “omission.” 155 Studies show that racial bias among medical providers contributes to differential treatment of their patients by race. 181 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 One such bias, that Black people are “superhuman” or less susceptible to pain, 180 , 181 , 186 , 187 has been used to justify slavery, eugenics, and mistreatment in medical research. 189 More broadly, the differential allocation of life‐saving treatment and procedures reflects an ideology of White supremacy that views White lives as more valuable and non‐White lives as “disposable.” 36 Similar patterns of discrimination, rooted in cultural racism, drive inequities in employment, housing, and the criminal legal system. 63 , 190 , 191

Cultural Racism Shapes Institutional Policies and Practices

Institutional policies can enable or constrain the actions of institutional agents while also operating at a more macrolevel to determine the allocation of societal resources. First, acts of discrimination enacted by those in positions of institutional power may be facilitated by institutional policies that fail to prevent racial discrimination and protect racially marginalized groups. For example, the disproportionate disciplining of Black and other racially marginalized students results from not only from individual teacher biases but also from school‐ and districtwide policies that allow this bias to become materialized through punitive and zero‐tolerance disciplinary strategies. 175 , 177

Second, discriminatory institutional policies, rooted in cultural racism, may directly shape inequity without racial discrimination on the part of institutional actors. This occurs in the case of automated or standardized systems, such as algorithms that determine allocation of health care, financial, or other resources. For example, race‐based medicine, 137 , 178 , 192 or “the misuse of race as a corrective or risk‐adjusting variable in clinical algorithms or practice guidelines,” 192 reflects cultural (mis)understandings of race as a biological factor. 137 , 192 , 193 Policies and tools built on race‐based medicine result in racial inequities in screening, diagnosis, and treatment 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 and, ultimately, inequities in health outcomes. 137 , 192 As this example illustrates, culturally rooted institutional policies need not require prejudice on the part of an individual institutional actor because cultural racism functions as a “a system of beliefs that become imbedded in educational, criminal justice, housing, health and economic institutions and a fundamental aspect of the social structure.” 33 Thus, institutional racism persists despite a changing roster of actors. 19 , 54 , 76

Pathways to Health

Structural and institutional racism both drive health inequities by shaping the distribution of societal risk and protective factors by race and by place, 199 which harms health via multiple mechanisms (Figure 1). Environmental and neighborhood risk factors can expose individuals to toxins, cause stress, and constrain access to health‐promoting resources and behaviors. 86 , 87 , 88 More broadly, diminished access to material and neomaterial resources diminishes the capacity to buffer stress and other harmful exposures, and impedes upward mobility. 6 , 8 , 11 , 19 Structural and institutional racism can also directly cause stress in the form of major lifetime experiences of institutional discrimination (e.g., being profiled by police, denied a home mortgage loan, etc.) 200 or “chronic contextual stress” associated with the awareness of structural oppression and social inequality. 60

Several studies have documented associations between collective racial prejudice (measured at the area level) and key markers of institutional racism (including racial inequities in school discipline 174 and being killed by law enforcement 201 ). The extent to which these patterns reflect the behavior of institutional actors (i.e., educators and law enforcement, respectively) operating within a culture of anti‐Blackness, and/or institutional policies that facilitate or fail to prevent differential treatment, remains a question in need of further investigation.

Cultural and Personally Mediated Racism

Personally mediated racism refers to prejudice and discrimination enacted among individuals. 19 Racial prejudice can be defined as “differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intentions of others according to their race.” 19 Racial discrimination refers to “differential actions toward others according to their race” 19 and can be seen as the behavioral manifestation of racial prejudice. 160 , 202 Racial discrimination occurring in institutional settings (e.g., hiring discrimination) is considered, for the purpose of this discussion, a form of institutional racism, as detailed above. Here, we describe the potential effects of cultural racism on individual‐level prejudice and racial discrimination as it manifests in day‐to‐day life.

Cultural Racism Shapes Racial Prejudice

The portrayal of different racial and ethnic groups in film, television, music, video games, and the news reflects cultural values, ideologies, and stereotypes. In turn, exposure to stereotypical or threatening media representations of marginalized racial and ethnic groups can increase racial prejudice among those who consume those media. 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 Stigmatizing language can also shape prejudice. For example, Darling‐Hammond and colleagues found that the use of the term “China Virus” on Twitter and the news to describe the COVID‐19 pandemic shaped collective biases about Asian Americans, 207 and Nguyen and colleagues found that those living in areas with greater levels of collective racial prejudice (as expressed on Twitter) showed higher levels of pro‐White/anti‐Black racial prejudice at the individual level. 208

Cultural Racism Shapes Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination manifests in many forms. Common presentations include subtle insults in day‐to‐day life (e.g., microaggressions), major lifetime events (e.g., racial hate crimes), and tolerance of discrimination. 19 , 200 By shaping racial prejudice, cultural racism may undergird these various forms of discrimination. 20 For example, consumption of media that portrays Black individuals as dangerous may increase racial prejudice and cause someone to—consciously or unconsciously—clutch their bag when walking past a group of Black teens, follow a Black shopper around in a store, or engage in other behavior that communicates suspicion and avoidance. 19 , 37 , 209 The “perpetual foreigner” stereotype, or the notion that non‐White people are inherently “less American” compared with White people, may cause someone to commit a racial microaggression, such as complimenting an Asian American's English proficiency or asking a Latine American, “Where are you really from?” 210

Cultural racism may also encourage more overt and violent acts of racial discrimination, including hate crimes. For example, in 2020, a group of White nationalists, operating within a culture of White supremacy, murdered Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging in his neighborhood. 211 In 2021, a White man entered several spas in Atlanta, Georgia, and murdered eight victims, six of whom were Asian women, citing a sex addiction. 212 The sexualization, objectification, and devaluation of Asian women in television, video games, and pornography is a salient example of cultural racism, 213 , 214 which may have motivated these violent acts, and sexual violence more broadly. Importantly, both everyday and major lifetime forms of racial discrimination may be experienced directly or vicariously, 78 , 209 as shown in Figure 1.

Finally, cultural racism creates an environment that is more tolerant of racial discrimination. 20 , 215 , 216 In a culture of White supremacy, there may be less will to intervene on discrimination when it occurs. Examples might include teachers turning a blind eye to race‐based bullying in schools, law enforcement ignoring racial discrimination and hate crimes, or other “acts of omission.” 134 , 155

Pathways to Health

The pathways through which personally mediated racial discrimination harms health have been well documented 20 , 101 , 217 and encompass biologic, cognitive/affective, and behavioral responses to chronic psychosocial stress, as shown in Figure 1.

As described above, racial discrimination—whether major or everyday—acts as a psychosocial stressor, triggering the body's biologic stress adaptation processes. 34 , 60 , 101 , 218 Although adaptive in the short term, repeated or ongoing activation of these processes can lead to multisystem dysregulation, resulting in accelerated biologic and cellular aging, increased risk of myriad chronic health conditions, and even mortality. 112 , 113 , 116 , 117 , 218 , 219 , 220 Studies show that greater chronicity of racial discrimination can increase and prolong activation of the stress response pathways. 84 , 221 , 222 , 223 , 224 , 225 Importantly, cultural racism creates an environment wherein racial discrimination can flourish, 74 thus increasing its pervasiveness and, we expect, subsequent stress responses among those for whom it is directly or vicariously experienced.

Cognitive and affective processes of threat appraisal, racial identity formation, and coping dispositions moderate the biological consequences of racism‐related stress. 85 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 218 , 226 , 227 For example, John Henryism 103 and Superwoman Schema85—adopted dispositions characterized by a strong tendency toward hard work and drive to succeed in the face of structural oppression—have their roots in cultural stereotypes, racial frames, and direct and vicarious experiences of racial discrimination 85 , 99 , 103 , 104 , 228 , 229 The Superwoman Schema is additionally characterized by presenting an image of strength, emotion suppression, and nurturing others while neglecting self‐care. 78 , 85 , 111 Studies show that the John Henryism disposition and Superwoman Schema may attenuate or exacerbate the effects of discrimination on health. 85 , 99 , 103 , 104 , 228

Anticipatory racism threat is another pathway through which personally mediated racism harms health. 20 , 78 , 230 Studies have documented a heightened state of vigilance in response to chronic racial discrimination, resulting in a lived anticipation of future racism experiences. 225 , 231 , 232 , 233 Anticipation and vigilance have been shown to predict various pathological states (e.g., cardiovascular, 234 , 235 sleep disturbance, 120 , 236 depression, 237 and others 40 , 106 , 232 ). Anticipation and vigilance may be exacerbated by cultural racism, wherein the threat of racial discrimination is made salient through media and the general social atmosphere, 230 or what Geronimus and colleagues term, the “surround.” 49

Finally, racial discrimination elicits a range of coping responses, including traditional health behaviors, such as diet, exercise, substance use, and risk‐taking, 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 as well as behavioral manifestations of the Superwoman Schema, such as self‐neglect. 78 , 85 , 111

Cultural and Internalized Racism

Internalized racism is defined as “acceptance by members of the stigmatized races of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth” 19 and has been associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes. 238 As shown in Figure 1, internalized racism may arise from exposure to cultural, structural, institutional, and personally mediated racism. 39 , 99 The concept of hegemony provides a clear link between cultural and internalized racism. As previously described, hegemony refers to the process by which the dominant group controls the construction of knowledge, frames, and a shared reality that functions to maintain their power. 38 , 39 , 46 “Ideological hegemony” 38 occurs when “the subjugated inculcate, seemingly by cultural osmosis, negative stereotypes and ideologies disseminated as taken‐for‐granted knowledge.” 41 Through this process, one who is oppressed may develop “a ‘sense of one's place’ which leads one to exclude oneself from the goods, persons, places and so forth from which one is excluded.” 52 In other words, the experience of exclusion, or “subliminal reminders in our everyday rounds of the degree to which our social identity group is—or isn't—valued by society” 49 is internalized to shape individuals' self‐views, self‐worth, and sense of belonging.

One prominent example of how cultural racism becomes internalized is through beauty standards. 239 Whether expressed in film, television, or advertising, conventional beauty standards reflect a White racial frame that privileges White styles and facial features. 239 Chronic exposure to these beauty standards can decrease self‐esteem among those who do not exhibit White features. 239 , 240 Internalized racism may also manifest as hatred or disgust for other members of one's own racial group, 39 , 241 , 242 , 243 resulting in “colorism” 243 or “defensive othering,” defined as “identity work engaged by the subordinated in an attempt to become part of the dominant group or to distance themselves from the stereotypes associated with the subordinate group.” 39 , 244

Pathways to Health

Internalized racism decreases self‐esteem, increases psychological distress, and encourages the adoption of unhealthy behaviors, such as alcohol consumption. 238 , 245 People may even resport to extreme dieting, skin whitening, chemical hair treatments, and plastic surgery in order to adhere to White beauty standards. 239 , 246 Moreover, colorism and defensive othering may cause cognitive dissonance, heightened intraracial tension, and decreased social cohesion within racial groups 39 , 244 while simultaneously reinforcing racial stratification by perpetuating White supremacy. 247 Finally, studies show that internalized racism may exacerbate the health effects of personally mediated racism and other stressors. 119 , 227 , 248

Direct Effects of Cultural Racism on Health

Cultural racism operates as an ambient social toxin—the water in which we swim—that may cause direct harm to racially marginalized groups, irrespective of these other dimensions of racism. 32 , 230 Experiences include viewing stereotypical, culturally appropriative, or degrading media representations 249 ; observing markers of White supremacy (i.e., racist monuments or other “environment indignities”) 32 , 250 ; being reminded of negative stereotypes (“stereotype threat” 105 , 251 , 252 ); and generalized awareness of one's stigmatized social status in society (“stigma consciousness” 49 , 253 , 254 ). Each of these exposures may cause psychological distress, heightened vigilance, 230 poorer performance on evaluative tasks, 252 and the adoption of unhealthy behaviors, 105 , 251 all of which undermine health. 32 , 74 , 254

As noted previously, a growing literature demonstrates associations between measures of cultural racism and adverse health outcomes 201 , 208 , 216 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 (for a review, see Michaels and colleagues 35 ); however, few studies have examined the mechanisms at play. Whether these associations represent direct effects, or effects mediated through other dimensions of racism, is an important area of future research to inform intervention. 35 Lastly, a recent study by Price and colleagues found that state‐level anti‐Black racial prejudice was associated with lower efficacy of psychotherapies targeting Black youth, 41 providing preliminary evidence of the potential moderating effect of cultural racism on clinical treatment outcomes. More research is needed to test this effect with other interventions, health outcomes, and populations.

Implications: An Example Linking Cultural and Other Levels of Racism with Racial Disparities in Drowning

Water is not just a metaphor; it takes literal and potentially deadly meaning when we consider the history of swimming in the United States. There is a stereotype today that “Black people can't/don't swim” 266 , 267 and a persistent lack of representation among recreational and high‐level swimmers alike. 267 These stereotypes arose, however, not because of an “innate” inability of Black persons to swim but because swimming pools were historically segregated owing to the combination of discriminatory policies and outright violence against Black swimmers. 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 Structural racism in urban planning, natural waterscape access, and housing development has restricted access to “blue space,” or pools and open water recreation areas, limiting opportunities for Black children to learn and practice swimming. 267 , 269 , 271

Not surprisingly then, stark racial disparities exist in unintentional drowning deaths. 272 Compared with their White counterparts, Black children aged 10–14 years old face 7.6 times the risk of drowning in swimming pools and American Indian/Alaska Native children face 3.2 the risk of drowning in open waters. 272 Black children are also more likely to report not knowing how to swim (64%) than Latine (45%) or White (40%) children. 273

These disparities are juxtaposed against historical accounts of Europeans learning how to swim from West Africans and narratives of Black slaves performing tasks involving swimming and saving their White masters after falling into water. 266 , 267 , 269 , 274 , 275 Cultural racism has obscured this history, creating racially essentialized understandings of who belongs in water.

Directions for Future Research on Cultural Racism and Health

According to Griffith, and colleagues, “eliminating health disparities is likely to require public health researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to identify, name and systematically address cultural racism as a social determinant of racial and ethnic health disparities.” 33 Based on our critical review of the literature, we agree with this assertion. In the sections that follow, we offer recommendations to guide future research on cultural racism and health. These recommendations are summarized in Appendix 3.

Expand Measurement of Cultural Racism to More Accurately Capture Its Multiple Dimensions

In order to quantify cultural racism and estimate its associations with health, we must first measure it. 276 , 277 However, as the water in which we swim, cultural racism is inherently difficult to capture empirically. Existing efforts have involved leveraging data from Project Implicit, The General Social Survey, Twitter, and Google Trends to measure the racial bias of multiple individuals in a defined geographic area and aggregating those individual measures to the group level. 35 These measures of area‐level (i.e., collective) racial prejudice, which likely capture the “shared social consciousness” dimension of cultural racism, have been associated with a variety of health outcomes 201 , 208 , 216 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 (for a review, see Michaels and colleagues 35 ), as well as measures of institutional and social inequity. 174 , 278 , 279 , 280

However, collective racial prejudice only represents one component of cultural racism. Advancing the study of cultural racism and health will require leveraging new data sources (e.g., historical records of racialized social shocks, media and advertising campaigns, cultural symbols and monuments) and methodologies (e.g., natural language processing, 281 image analysis 282 ) to measure the other dimensions of cultural racism. We also recommend that measurement advances include qualitative 283 and participatory 284 methods. Such approaches can advance the field's knowledge and support the development of more nuanced and valid quantitative measures.

Researchers may then examine how the different dimensions of cultural racism (e.g., collective racial prejudice, language and symbols, media portrayals [as shown in Figure 2]) covary across time and (physical and/or digital) space. For example, Darling‐Hammond and colleagues found that racially stigmatizing language (i.e., “China Virus”) shaped group‐level attitudes about Asian Americans during the COVID‐19 pandemic, illuminating key associations among different dimensions of cultural racism (rhetoric and collective prejudice, respectively). 207

Once the various dimensions of cultural racism have been thoughtfully measured, one next step could be to develop and validate a multidimensional culture racism index (for an example, see Price and colleagues 41 ). This index would need to be created with careful attention to the fact that cultural racism is fluid and context dependent. 18 , 36 Attending to this dynamism could be achieved through the development of place‐based indices and/or indices that are sensitive to real‐time cultural shifts, racialized events, and social shocks (for example, see Criss and colleagues 285 , Darling‐Hammond and colleagues, 207 Hswen, 257 and Nguyen and colleagues 286 ). Considering the ways in which cultural racism intersects with values of capitalism, patriarchy, and other ideological systems, scholars could develop measures of “cultural intersectionality” to mirror innovations in measuring structural intersectionality. 287

Empirically Test Bidirectional and Interactive Relationships Between Cultural and Structural Racism

As discussed, cultural and structural racism are mutually reinforcing; a culture of White supremacy provides the ideological environment within which structural racism is built and maintained while structural arrangements and policy regimes shape cultural racism by signaling whose lives are worth investing in and protecting. Examining the relationships between cultural and structural racism, and independent and joint associations with health outcomes, will facilitate a more comprehensive assessment of racism and how it operates to undermine health.

One potentially fruitful direction would be to explore associations between cultural racism and indicators of structural racism, such as policy regimes. A team of public health and legal scholars recently developed a comprehensive database of state‐level racism‐related laws and policies that shape the inequitable allocation of social, economic, and political resources among racially marginalized groups relative to White people. 11 Using these data, researchers could explore associations between markers of cultural racism and variation in the location, timing, and concentration of racism‐related policies. Researchers could then examine whether cultural and structural racism interact to shape health outcomes and inequities. Questions might include the following: Are the health consequences of discriminatory or exclusionary policies exacerbated in areas with higher levels of cultural racism? Are the health benefits of equitable or reparative social policies attenuated by cultural racism? Answering these questions provides the evidence base needed to guide contextually rooted policy interventions to promote health equity.

Empirically Test Pathways to Health

We have detailed several key mechanisms through which cultural racism, often mediated through the other dimensions of racism, may “get under the skin” to harm health. These include material, neomaterial, place‐based, cognitive/affective, behavioral, and biologic processes operating across the life course. However, these relationships are largely speculative, based on social theory and biological plausibility. An important next step for future research will be to empirically test these pathways.

Researchers could estimate the association between cultural racism and health outcomes and then explore whether and to what extent this association is mediated through structural, institutional, personally mediated, or internalized racism and their sequalae. For example, do people living in areas with greater levels of cultural racism experience more everyday racial discrimination, and does this discrimination mediate associations with health outcomes? Or is there an effect of cultural racism on health, regardless of direct experiences of discrimination? If so, which processes might be at play, such as vigilance? Although the pathway from cultural racism to vigilance to health has been theoretically explicated, 49 , 230 it is yet to be empirically tested. In addition to mediation, researchers could explore whether the association between cultural racism and health is moderated by other forms of racism. We emphasize that these research questions and analytic models must be developed with careful attention to intersectionality and the life course (e.g., measuring intersections of cultural and structural racism with cultural and structural sexism, 288 examining impacts of cultural racism exposure in childhood on long‐run health outcomes). 127

Qualitative research, an epistemological project that centers the lived experiences of people who are directly impacted by the topic of study, can help deepen our understanding of cultural racism and how it shapes health. For example, Criss and colleagues conducted online focus groups with women of childbearing age to understand how they experience direct and vicarious racism online, strategies they use to cope with these experiences, and how they understand its impacts on their health. 289

Develop and Test Interventions to Reduce Cultural Racism

In this paper, we have drawn on interdisciplinary social science theory and empirical evidence to advance the thesis that cultural racism acts, alongside structural racism, as a fundamental cause of health inequities. Developing innovative measurement strategies and testing pathways to health will help researchers further refine their conceptualization of cultural racism and the mechanisms through which it becomes embodied. Yet, in the meantime, mounting evidence that a culture of White supremacy harms health necessitates immediate action. Applying “public health critical race praxis” 122 to cultural racism means developing and testing interventions to reduce cultural racism. What might such interventions look like?

Narrative change, defined as “the effort to challenge, modify, or replace existing narratives that perpetuate inequity and uphold an unjust status quo, through the creation and deployment of new or different narratives,” 55 p6 represents one potentially promising for reducing cultural racism and building community power. 290 , 291 Shifting narratives could take many forms, such as removing harmful symbols (e.g., racist monuments), creating visible signs valuing diversity, amplifying contributions of people of color, or celebrations of history and culture. Prior evidence suggests that race‐affirming messaging can reduce racial prejudice among individuals, 146 shift collective biases, 292 and improve mental health among racially marginalized groups. 293 Given that cultural racism is rooted in the values of White people, interventions targeting White people may also be needed. A recently funded initiative to promote and scale critical conversations about race with White parents and children holds promise for reducing cultural racism and advancing equity for generations to come. 294

We have argued that cultural racism undergirds all other dimensions of racism. Based on this analysis, one important question is whether efforts to reduce cultural racism could begin to erode internalized, personally mediated, institutional, and structural racism and their health consequences. Given that structural and cultural racism are mutually reinforcing, would eradicating cultural racism be sufficient to eliminate health inequities, or would a wraparound approach to intervene on cultural and structural forms of oppression be needed? What might this look like? Multisector collaborations, in partnership with those who directly experience racism in its many forms, will be essential. Many questions remain, and more work is required to better understand cultural racism; how we can measure it; how it shapes health; and how we can work alongside communities to dismantle cultural racism and advance health equity.

Conclusion

Racism has been described as an iceberg, 3 , 4 with overt acts of discrimination representing the “tip of the iceberg,” 3 p131 which we can see, and structural and institutional forms of racism representing the base of the iceberg looming below the surface. In this paper, we have extended the metaphor to offer cultural racism as the murky water surrounding the iceberg, which simultaneously upholds and obscures its base. It is so pervasive and taken for granted that we often cannot see it, just as the fish cannot perceive the water in which it swims. We have drawn on theory and empirical evidence to argue that cultural racism is, along with structural racism, a fundamental cause of racial health inequities. Future research measuring and documenting the health effects of cultural racism, independently and in concert with other forms of racism, is a critical next step toward understanding and ultimately addressing the root causes of racial health inequities. Such efforts hold the potential to inform a broader set of policies and interventions to promote health equity.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures: No disclosures were reported.

Acknowledgments: Research reported in this publication was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant F31HL151284 [to E.K.M.]), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grants R00MD012615 and R01MD015716 [to T.T.N.]), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Agreement No. 1OT2OD032581‐01. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the NIH.

Appendix 1. Cultural Racism Constructs, Components, and Examples

| Construct | Components and Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Values + belief systems |

|

Macro/fundamental concept does not support specific examples |

|

||

|

||

| Shared social consciousness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Cultural expressions | How we “see” and “hear” the ideologies of White superiority in society, through: | Racially charged political rhetoric, confederate flags and monuments, racial stereotypes, degradation; cultural stereotypes expressed in music, TV, film, news, fashion, and social media |

|

||

|

Appendix 2. Dimensions of Racism and Relationship to Cultural Racism

| Dimension of racism | Definition | Relationship with cultural racism | Examples | Pathways to health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Values and belief systems—operating at the level of our shared social consciousness—that privilege and protect White people and power, and are expressed in the language, symbols, and media representations of dominant society | —– | See Appendix 1 |

Shapes health via structural, institutionalized, personally mediated, and internalized racism Exerts direct effects on health: stereotypical media representations, environmental reminders of White supremacy, and generalized awareness of stigmatized social status cause psychological distress and vigilance, leading to physiological dysregulation and multiple adverse health outcomes. |

| Structural | Cooperation of multiple social institutions—including housing, health care, education, carceral, banking, among others—to concentrate wealth, power, and ultimately health among White people relative to minoritized racial groups. 5 , 6 , 7 , 76 |

|

|

Shape distribution of societal risk and protective factors by race Direct stress caused by major lifetime experiences of discrimination “Chronic contextual stress” 60 associated with the awareness of inequality in society and structural oppression |

| Institutional | Racism occurring within specific institutional settings, such as schools, the workplace, the judicial system, and medical system 19 , 33 |

|

|

Same as structural, but focus is on single‐institution pathways (e.g., school‐based discrimination leading to disparate educational trajectories and subsequent health impacts) |

|

|

|||

| Personally mediated | Prejudice and discrimination enacted between individuals in day‐to‐day life 19 |

|

|

Racial discrimination acts as psychosocial stressor, triggering the body's stress adaptation processes Threat appraisal and dispositions moderate the effects of racism‐related stress on health Adoption of unhealthy behaviors as coping response |

| Internalized | “The individual inculcation of the racist stereotypes, values, images, and ideologies perpetuated by the White dominant society about one's racial group, leading to feelings of self‐doubt, disgust, and disrespect for one's race and/or oneself” 39 | Ideologies and values of White supremacy, as expressed in the language, symbols, and mass media of dominant society become internalized to shape individuals’ self‐views, self‐worth, and behavior. |

|

White beauty standards erode self‐esteem and can lead to harmful behaviors such as skin whitening Colorism and defensive othering can lead to cognitive dissonance, psychological distress, harmful compensatory behaviors, and heightened tension and decreased social cohesion |

Appendix 3. Directions for Future Research

| Direction | Description | Example research question |

|---|---|---|

| Expand measurement of cultural racism to more accurately capture its multiple dimensions | Examine geo‐temporal associations among collective racial prejudice, stigmatizing political rhetoric, racist monuments and symbols, and stereotypical or degrading depictions of racially minoritized groups in TV, film, music, advertising, news, fashion, and social media. Develop and test a comprehensive, multidimensional cultural racism index. Incorporate qualitative methods to inform the development of more nuanced and valid measures. | Do counties with a greater concentration of confederate monuments have higher levels of Twitter‐expressed negative racial sentiment? |

| Empirically test bidirectional relationships between cultural and structural racism, across time and place | Using the cultural racism index suggested above, explore associations between cultural racism (as a construct and its subcomponents) and indicators of structural racism, including policy regimes, racialized rules, and interinstitutional connections. | Is cultural racism (each dimension and a comprehensive index) associated with the timing and location of various racism‐related laws and policies (an indicator of structural racism)? Do cultural and structural racism interact to pattern health outcomes and inequities? |

| Empirically test pathways to health | Examine material, neomaterial, place‐based, psychosocial, behavioral, and biologic processes through which cultural racism—operating directly or indirectly through the other dimensions of racism—“gets under the skin” to shape health across the life course for individuals of varying social identities and intersectionalities. Use qualitative methods to understand how people experience and cope with cultural racism. | Do individuals living in areas with greater levels of cultural racism experience more everyday racial discrimination, and does this discrimination mediate or moderate associations with health outcomes? Are associations differential based on intersectional identities and stage in the life course? |

| Develop and test interventions to reduce cultural racism | Conceptualize a culturally antiracist research agenda that situates cultural racism as the fundamental determinant of all other forms of racism and health inequities; envision creative strategies to intervene on cultural racism and its various dimensions, and test impacts on other forms of racism and health inequities. | How might the removal of harmful symbols (e.g., racist monuments) or the creation of visible signs valuing diversity, contributions of people of color, culture, or history celebrations reduce collective racial prejudice and promote health? |

References

- 1. Bourdieu P, Wacquant LJ. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41:311‐330. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff‐Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):130‐151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gee CG, Ro A. Racism and discrimination. In: Trinh‐Shevrin C, Islam NS, Rey MJ, eds. Asian American Communities and Health: Context, Research, Policy and Action. 1st edition. Jossey‐Bass; 2009:364‐402. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:768‐773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gee GC, Hicken MT. Commentary – structural racism: the rules and relations of inequity. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(Suppl 1):293‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groos M, Wallace M, Hardeman R, Theall KP. Measuring inequity: a systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018;11(2):13. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alson JG, Robinson WR, Pittman L, Doll KM. Incorporating measures of structural racism into population studies of reproductive health in the United States: a narrative review. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):49‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agénor M, Perkins C, Stamoulis C, et al. Developing a database of structural racism–related state laws for health equity research and practice in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(4):428‐440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krieger N, Feldman JM, Kim R, Waterman PD. Cancer incidence and multilevel measures of residential economic and racial segregation for cancer registries. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(1):pky009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adkins‐Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(4):539‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chambers BD, Erausquin JT, Tanner AE, Nichols TR, Brown‐Jeffy S. Testing the association between traditional and novel indicators of county‐level structural racism and birth outcomes among Black and White women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(5):966‐977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chantarat T, Van Riper DC, Hardeman RR. The intricacy of structural racism measurement: a pilot development of a latent‐class multidimensional measure. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sewell AA. Political economies of acute childhood illnesses: measuring structural racism as mesolevel mortgage market risks. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(Suppl 1):319‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Understanding and addressing the impact of structural racism and discrimination on minority health and health disparities (R01 clinical trial optional) . National Institutes of Health. 2021. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa‐files/RFA‐MD‐21‐004.html

- 18. Hicken MT, Kravitz‐Wirtz N, Durkee M, Jackson JS. Racial inequalities in health: framing future research. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:11‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105‐125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neblett JEW, Bernard DL, Banks KH. The moderating roles of gender and socioeconomic status in the association between racial discrimination and psychological adjustment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2016;23(3):385‐397. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown AF, Ma GX, Miranda J, et al. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S72‐S78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alang S, Hardeman R, Karbeah JM, et al. White supremacy and the core functions of public health. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(5):815‐819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brunsma DL, Embrick DG, Shin JH. Graduate students of color: race, racism, and mentoring in the White waters of academia. Sociol Race Ethnic. 2017;3(1):1‐13. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feagin JR. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter‐Framing. 3rd edition. Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. LaFave S, Suen J, Seau Q, et al. Racism and older Black Americans’ health: a systematic review. J Urban Health. 2022;99(1):28‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peavy AC, Shearer ET. Reifying contemporary versions of liquified racism: Black representation in competitive swimming. J Sport Soc Issues. 2022;46(3):247‐268. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waldron IR. There's Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities. Fernwood Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maxwell KE. Deconstructing whiteness: discovering the water. Counterpoints. 2004;273:153‐168. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cramer K. Understanding the role of racism in contemporary US public opinion. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2020;23:153‐169. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murky . Merriam‐Webster. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.merriam‐webster.com/dictionary/murky

- 32. Cogburn CD. Culture, race, and health: implications for racial inequities and population health. Milbank Q. 2019;97(3):736‐761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Griffith DM, Johnson J, Ellis KR, Schultz AJ. Cultural context and a critical approach to eliminating health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1):71‐76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8):10.0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Michaels EK, Board C, Mujahid MS, et al. Area‐level racial prejudice and health: a systematic review. Health Psychol. 2022;41(3):211‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hicken MT, Miles L, Haile S, Esposito M. Linking history to contemporary state‐sanctioned slow violence through cultural and structural racism. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2021;694(1):48‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lamont M, Beljean S, Clair M. What is missing? Cultural processes and causal pathways to inequality. Socioecon Rev. 2014;12(3):573‐608. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gramsci A. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Hoare Q, Smith GN, trans‐eds. International Publishers; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pyke KD. What is internalized racial oppression and why don't we study it? Acknowledging racism's hidden injuries. Sociol Perspect. 2010;53(4):551‐572. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hicken MT, Lee H, Hing AK. The weight of racism: vigilance and racial inequalities in weight‐related measures. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:157‐166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price MA, Weisz JR, McKetta S, et al. Meta‐analysis: are psychotherapies less effective for Black youth in communities with higher levels of anti‐Black racism? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(6):754‐763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilkerson I. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. Random House; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harris CI. Whiteness as property. Harv Law Rev. 1993;106(8):1707‐1791. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Corces‐Zimmerman C, Thomas D, Collins EA, Cabrera NL. Ontological expansiveness. In: Casey ZA, ed. Encyclopedia of Critical Whiteness Studies in Education. Brill; 2020:432‐438. Critical Understanding in Education; vol 2. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kent‐Stoll P. The racial and colonial dimensions of gentrification. Sociol Compass. 2020;14(12):1‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Omi M, Winant H. Racial Formation in the United States. Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Link BG, Phelan J. Stigma power. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:24‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363‐385. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Geronimus AT, James SA, Destin M, et al. Jedi public health: co‐creating an identity‐safe culture to promote health equity. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:105‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Payne BK, Vuletich HA, Lundberg KB. The bias of crowds: how implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychol Inq. 2017;28(4):233‐248. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blair IV, Brondolo E. Moving beyond the individual: community‐level prejudice and health. Soc Sci Med. 2017(183):169‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bourdieu P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hehman E, Calanchini J, Flake JK, Leitner JB. Establishing construct validity evidence for regional measures of explicit and implicit racial bias. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2019;148(6):1022‐1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bonilla‐Silva E. Racism without Racists: Color‐Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 2nd edition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nikki Kalra CBF, Robles L, Stachowiak S. Measuring Narrative Change: Understanding Progress and Navigating Complexity. ORS Impact; 2021. [Google Scholar]