Abstract

Introduction

An aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a locally aggressive primary bone neoplasm. ABC of the clavicle is rare with only a few reported cases in the literature.

Presentation of case

We report the case of a 10-year-old boy who presented with an ABC at the right acromial end of the clavicle. The patient underwent intralesional curettage and allogenic bone grafting. Moreover, the patient's arm was placed in a sling for 2 weeks postoperatively. The patient had a satisfactory outcome after 11 years, with excellent Toronto Extremity Salvage, Quick-Dash, and Musculoskeletal Tumor Society scores.

Discussion

Clavicular ABCs are uncommon. Early diagnosis helps to prevent pathological fractures. Adjuvant therapies might help decrease recurrence.

Conclusion

ABC should be considered an important differential diagnosis for clavicular swelling and masses. The best results can be achieved using curettage and void-filled bone grafts.

Level of evidence: 4.

Keywords: Aneurysmal bone cyst, Clavicle, Benign tumor, Shoulder, Orthopedic oncology, Case report

Highlights

-

•

An aneurysmal bone cyst is a locally aggressive primary bone neoplasm.

-

•

aneurysmal bone cyst of the clavicle is rare.

-

•

aneurysmal bone cyst should be considered an important differential diagnosis.

1. Introduction

The clavicle is the only long bone that courses along a horizontal axis. In contrast to other long bones, the clavicle lacks a definite medullary cavity and ossifies via intramembranous ossification. It has two primary and one secondary ossification center at the sternal end, which predominantly contribute to the growth [1]. The clavicle is the first bone to ossify in an embryo, approximately in the 5th month of gestation [2]. The vascular supply to the clavicles is minimal, which might explain the rarity of clavicular tumors [3].

An aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a primary bone neoplasm known to exhibit locally aggressive behavior [4]. They represent approximately 1–6 % of all bone tumors [5]. ABC usually affects the metaphysis of long bones, most commonly the proximal humerus, distal femur, and proximal tibia [6]. Primary bone tumors of the clavicles including ABC are rare [4]. Only a few such cases have been reported in the literature. Most of the reports are from broader studies that do not specifically describe the ABC of the clavicle.

ABC is commonly observed during childhood and adolescence, with 90 % of the lesions identified in individuals <30 years of age. ABC has a slightly more female predilection with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.16 [7].

ABCs are solitary tumors that can be divided into primary neoplasms or secondary lesions. Primary neoplasms are translocation driven. However, secondary lesions that represent 30 % of all ABCs are not considered neoplasms as no translocations are observed in them. They are usually associated with giant cell tumors, osteoblastoma, and osteochondromas [8].

The clinical presentation includes pain and swelling, and due to the locally aggressive behavior of the tumor, pathologic fractures can occur, which in turn aggravates the symptoms. Moreover, spine lesions may cause a mass effect leading to neurological deficits [9].

Plain film radiography exhibits an eccentric radiolucent cystic lesion surrounded by a thin layer of cortical bone. Multilocular appearance results from the trabeculation within the lesion that gives ABC a “soap bubble appearance” [10].

We report the case of a 10-year-old boy with a rare presentation of ABC. Herein, we describe the patient's presentation, radiographic findings, surgical management, and clinical and radiographic outcomes. The authors obtained the patient's parents informed written consent for the print and electronic publication of the case report. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria [11].

2. Case presentation

A healthy 10-year-old boy with a history of right clavicle fracture 7 months before the presentation was managed non-surgically. The patient complained of right shoulder pain, limited range of motion, and swelling over the right shoulder persistent for 4 months. Physical examination revealed a generally healthy patient weighing 36 Kg. Right shoulder examination revealed a tender, non-pulsatile, hard mass (2 × 2 cm) over the right distal clavicle, overlying skin discoloration, and no palpable axillary lymph nodes. The active range of motion was limited due to pain to 160° forward flexion and approximately 130° abduction. Furthermore, the patient had palpable radial and ulnar pulses, normal sensory and motor examinations, and normal muscular strength.

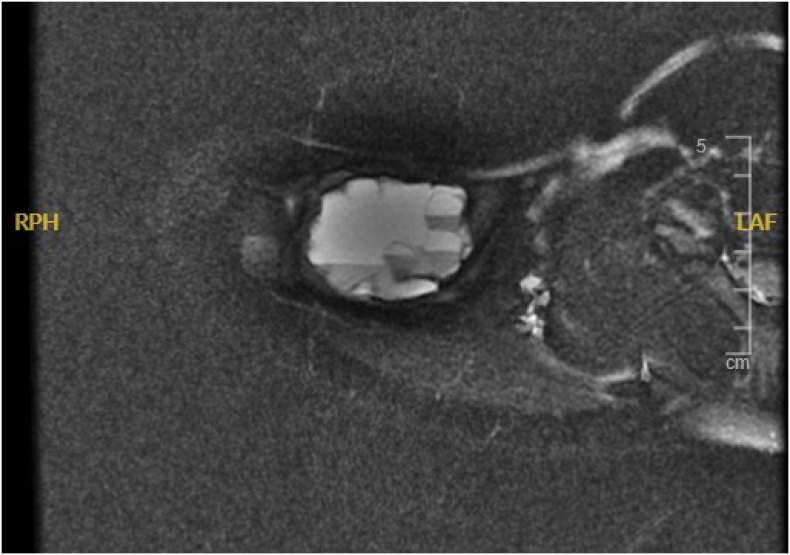

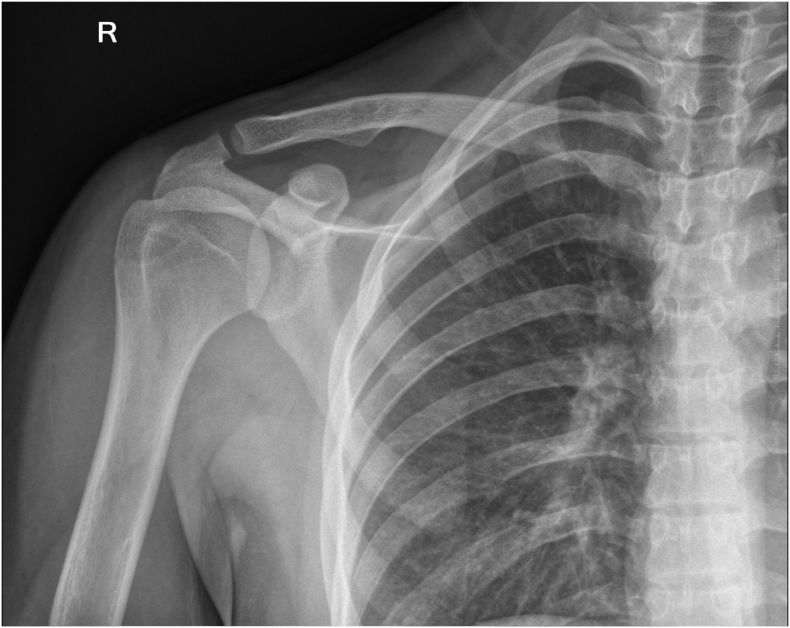

Plain film radiographs revealed an expansile bubbly osteolytic lesion with a surrounding undisturbed rim of cortical bone over the distal end of the right clavicle (Fig. 1). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a multiseptated fluid-filled cystic mass (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Biopsy revealed a histo-pathologically hemorrhagic mass surrounded by a shell of reactive bone, while microscopic examination revealed pseudocysts with the septal proliferation of fibroblasts filled with red blood cells and brown hemosiderin. The patient underwent intralesional curettage and bone grafting through an elliptical incision centered over the lesion. Furthermore, the arm of the patient was placed in a sling postoperatively for 2 weeks.

Fig. 1.

Plain radiography of the right clavicle at presentation showing expansile bubbly osteolytic lesion.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography of the right shoulder at presentation.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography of the right shoulder at presentation.

Fig. 4.

MRI of the right shoulder at presentation showing multiseptated fluid-filled cystic mass.

Fig. 5.

MRI of the right shoulder at presentation showing multiseptated fluid-filled cystic mass.

The patient was followed up for 11 years. No recurrence was observed at the follow-ups. Cosmetic, radiographic, and functional outcomes were excellent (Toronto Extremity Salvage Score, 100; QuickDash,100; Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score 30(Fig. 6) [12,13].

Fig. 6.

Plain radiography of the right clavicle at follow-up after 11 years showing no recurrence.

3. Discussion

Clavicular tumors are rare. Although the clavicle is a long bone, it has the oncological characteristics of flat bones [2]. Clavicular ABCs are uncommon. In general, the acromial end of the clavicle is more commonly affected by the ABC and other clavicular lesions. The vulnerability of the acromial end could be attributed to differences in sternal and acromial end development [3].

Although it is an unusual site for ABC in the usual age group, it should be included in the differential diagnosis. Given the patient's age, imaging, and histological findings, an open biopsy of a frozen tissue sample should assist in ruling out telangiectatic osteosarcoma before or during the index surgery [6].

Multiple treatment options are available for ABC, ranging from non-surgical options such as embolization to more aggressive surgical management including bone resection [6]. The gold standard for ABC management remains intralesional curettage with or without bone grafting, depending on the remaining void [10]. The same treatment protocol was followed in this case. Jaffe and Lichtenstein's original description of ABC management included curettage and bone grafting of the void which remains the modern gold standard [14]. As clinical publications have demonstrated a high recurrence rate and further understanding of the pathophysiology of ABCs has evolved, management strategies have also expanded. ABC has a relatively high recurrence rate, up to 59 % in certain cases [15]. As a result, multiple adjuvant therapies have been developed to minimize the recurrence rate, including the use of cement, phenol, cryotherapy, argon beam, and high-speed burr. However, no detailed studies have compared the efficacy of adjuvant therapies, with most evidence being obtained from case-series studies.

4. Conclusion

ABCs are benign, locally aggressive bone lesions with a high recurrence rate, however, those involving the clavicle are rare. The current standard management is curettage with a void-filling graft; however, multiple adjuvants have been developed to minimize recurrence rates. Despite its rarity, ABC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of clavicular swelling and masses.

Financial disclosure

This case report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents for publication and any accompanying images.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Nothing to disclose.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Haque M.K., Mansur D.I., Sharma K. Study on curvatures of clavicle with its clinical importance. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 2012;9:279–282. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v9i4.6344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapoor S., Tiwari A., Kapoor S. Primary tumours and tumorous lesions of clavicle. Int. Orthop. 2007;32:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren K., Wu S., Shi X., Zhao J., Liu X. Primary clavicle tumors and tumorous lesions: a review of 206 cases in East Asia, archives of Orthopaedic and trauma. Surgery. 2012;132:883–889. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser C.L., Yeung C.M., Raskin K.A., Lozano-Calderon S.A. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the clavicle: a series of 13 cases. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019;28:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dormans J.P., Hanna B.G., Johnston D.R., Khurana J.S. Surgical treatment and recurrence rate of aneurysmal bone cysts in children. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2004;421:205–211. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000126336.46604.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mankin H.J., Hornicek F.J., Ortiz-Cruz E., Villafuerte J., Gebhardt M.C. Aneurysmal bone Cyst: a review of 150 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:6756–6762. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.15.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leithner A., Windhager R., Lang S., Haas O.A., Kainberger F., Kotz R., Cyst Aneurysmal Bone. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1999;363:176???179. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199906000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez V., Sissons H.A. Aneurysmal bone cyst. A review of 123 cases including primary lesions and those secondary to other bone pathology. Cancer. 1988;61:2291–2304. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880601)61:11<2291::aid-cncr2820611125>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novais E.N., Rose P.S., Yaszemski M.J., Sim F.H. Aneurysmal bone Cyst of the cervical spine in children. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2011;93:1534–1543. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.j.01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park H.Y., Yang S.K., Sheppard W.L., Hegde V., Zoller S.D., Nelson S.D., Federman N., Bernthal N.M. Current management of aneurysmal bone cysts. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2016;9:435–444. doi: 10.1007/s12178-016-9371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gummesson C., Ward M.M., Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (quick DASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2006;7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayer M., Doyle S., Sangha N., Grimer R. The Toronto extremity salvage score in Unoperated controls: an age. Gender, and Country Comparison, Sarcoma. 2012;2012:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/717213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James A.G. Solitary (unicameral) bone cyst. Arch. Surg. 1948;57:137. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1948.01240020140011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biesecker J.L., Marcove R.C., Huvos A.G., Miké V. Aneurysmal bone cysts. A clinicopathologic study of 66 cases. Cancer. 1970;26:615–625. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197009)26:3<615::aid-cncr2820260319>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]