Abstract

Introduction

Small gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are often asymptomatic. However, large tumors can cause symptoms like abdominal pain and GI bleeding. We experienced a unique case where a giant GIST was incidentally found by CT scanning during emergency treatment for dizziness.

Presentation of case

A 61-year-old man presented temporary dizziness after exercising three days ago before his admission. Enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large circular mass in the right upper abdominal cavity, with a maximum cross-sectional size of approximately 132 mm × 155 mm. Biopsy and genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis of GIST. The patient underwent successful radical surgery and was discharged at 12th post-operative day without any complications. The patient now is taking imatinib as an adjuvant targeted therapy.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the digestive tract with diverse clinical presentations according to their sites and sizes. As in this case, the patient's primary complaint was dizziness, which is uncommon for GISTs. Initial workup, including three-dimensional rebuilding of the enhanced CT scanning and biopsy, was given before surgery. Finally, despite the tumor's large size and attachment to adjacent structures, R0 resection was accomplished without intraoperative rupture.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of healthcare providers vigilant in identifying GISTs with unusual symptoms in emergency situations. A systematic and comprehensive examination can be and should be performed to confirm diagnosis and determine the feasibility of R0 resection. By sharing this unique case, we aim to enhance the understanding of GIST and increase awareness among clinicians about their varied presentations.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Giant, Dizziness, Surgery, Case report

Highlights

-

•

The clinical manifestations of large GISTs often present with digestive symptoms.

-

•

However, this case presented transient dizziness as primary symptom during emergency treatment.

-

•

Healthcare providers should be vigilant in identifying GISTs with unusual symptoms.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the prevailing form of soft tissue sarcoma that can develop in anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract. [1] GISTs originally arise from Cajal's interstitial cell and are characterized by mutation of KIT and platelet derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) [2]. Histologically, GISTs can be classified into two main types, spindle-cell GIST, mainly found in mutated KIT or BRAF GIST (in 70 % of cases), and epithelioid-cell GIST (20 %), mainly found in PDGFRA or succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) GIST. Ten percent have a mixed morphology. They typically present in older individuals and are most common in the stomach (60–70 %), followed by the small intestine (20–25 %). GISTs are often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on imaging. [3] However, the clinical presentations of GIST are highly variable depending on their location and size. Small tumors are usually incidental findings on operation, endoscopy or imaging studies for other reasons. Symptoms can range from anemia and weight loss to GI bleeding, abdominal pain, and the presence of palpable mass. Patients may present with acute abdomen, obstruction, perforation or rupture, and peritonitis. Other presentations include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension [4].

In cases where GISTs are large and non-metastatic, surgery is the criterion standard treatment approach. [5,6] The goal of resection is complete macroscopic and microscopic resection (R0) without rupture of the pseudo capsule [7]. We here reported a compelling case of a giant stomach GIST encountered CT scanning in the emergency room conducted for dizziness. We successfully performed an en bloc surgical operation of the tumor, and we describe the details of the procedure and outcome. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE Criteria (include citation) [19].

2. Case report

A 61-year-old male patient presented transient dizziness after exercising three days ago. He gradually relieved after lying flat without conscious loss. Under emergency treatment in the local hospital, abdominal CT revealed a space-occupying lesion in the upper right abdomen. No previous history of smoking or alcohol consumption. No special medical or surgical history. Also, there are not any abnormal health information regarding first-degree relatives. After admission, relevant examinations were completed, and hemoglobin was 97 g/L. CEA, AFP, CA19–9, and CA72–4 indicators were all normal. Enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large circular mass in the right upper abdominal cavity, with a maximum cross-sectional size of approximately 132 mm × 155 mm, the CT value was about 32HU, no abnormal enlarged lymph nodes were found, high-density aggregation was seen around the liver, in the right iliac fossa, and in the pelvis, the CT value was about 46HU, enhanced scanning showed slight enhancement (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Enhanced CT scan reveals a large circular soft tissue density mass in the right upper abdominal cavity, with a maximum cross-sectional size of approximately 132 × 155 mm, CT value was about 32HU, the arterial phase of the enhanced scan showed obvious enhancement, CT value was about 47HU. the boundary with the gastric wall, duodenal wall, and gallbladder wall was unclear, the pancreas was compressed, the density of Mesentery around the lesion increased unevenly, no abnormal enlarged lymph nodes were found. High density clusters were seen around the liver, right iliac fossa, and pelvic cavity, CT value was about 46HU, the enhanced scan showed slight enhancement.

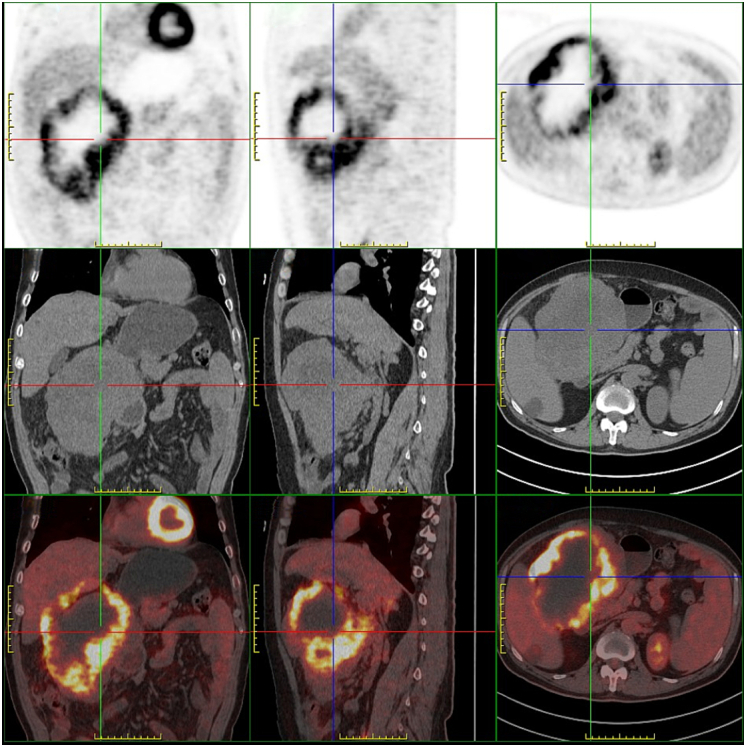

PET-CT also showed a soft-tissue-density mass in the right abdominal cavity, with uneven density and irregular shape. Multiple low-density necrotic areas can be seen inside, with a circular increase in 18F-FDG uptake and SUV max of 11.1. The lesion area was approximately 158 mm × 127 mm × 171 mm (length × wide × High) (Fig. 2). The gastroscopy indicated that there was a protrusion in the small curvature of the gastric body, Yamada I type, with a size of about 8 cm × 10 cm. The surface mucosa was smooth, and the gastric cavity was compressed and deformed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

PET-CT shows a soft tissue density mass in the right abdominal cavity, with uneven density and irregular shape. Multiple low-density necrotic areas can be seen inside, with a circular increase in 18F-FDG uptake and SUVmax of 11.1. The lesion area is approximately 158 mm × 127 mm × 171 mm (length × wide × High), closely related to the adjacent gastric antrum and duodenal wall, gallbladder wall, and right lobe of the liver.

Fig. 3.

Gastroscopy indicates a small curvature of the gastric body with a protrusion, about 8cmX10cm in size.

Pathological examination of CT guided puncture biopsy specimen showed spindle cell tumor with large necrotic areas, rich and dense cells, mild to moderate dysplasia, the mitotic appearance of 2/50 HPF. Combined with immunohistochemical results, we considered gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Due to limited puncture tissue, and in combination with tumor size of approximately 13.2 cm × 15.5 cm by clinical imaging, height grade in danger level was considered; Further risk classification and prognosis grouping are recommended after total resection of the tumor. Immunohistochemical results (S0048045–1): Ki67 (8 %+), P53 (partial+), CD34 (+), CD117 (+), S100 (−), SMA (+), Desmin (+), DOG-1 (+), PDGFR (weak+), SDHB (+).

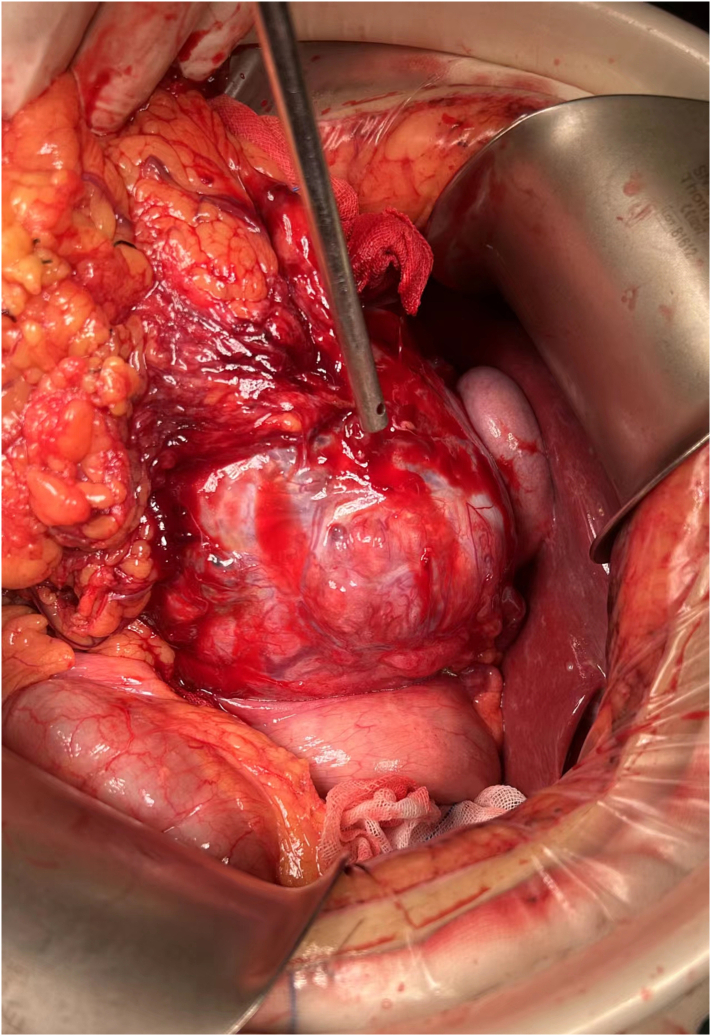

The patient is placed in a supine position and intubated under general anesthesia. Intraoperative exploration: Preliminary exploration revealed that the greater omentum covered and enveloped the abdominal mass. The ultrasonic scalpel removed the adhesion between the greater omentum and the surface of the tumor and the surrounding area. After partial excision of the greater omentum, the tumor was further exposed. The diameter of the tumor was about 16 cm. It was fragile, easy to bleed, expansive, dark blue in color, complete in capsule, uneven in surface, and distended in blood vessels. It did not invade the liver, gallbladder, and Transverse colon. We Installed frame hooks, fully exposed the surgical area, and continued to use blunt and free methods to release the adhesion around the tumor. Upon further exploration, it was found that the tumor's root originated from the gastric body's small curvature, which was considered an exogenous gastric stromal tumor (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative exploration: the tumor originates from the lesser curvature of the stomach and adheres to the greater omentum, without invading the liver and gallbladder.

Postoperative pathology: spindle cell tumor with cell dysplasia, mitotic figures>10/50 HPF, large necrotic areas visible, combined with immunohistochemical results, consistent with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), with a tumor size of approximately 19 cm × 16 cm × 11 cm (Fig. 6), risk grade: high risk (prognosis group: 6b); The tumor invaded the serous layer of the gastric wall to the Lamina propria of the mucosa, and the omental tissue was also seen, no tumor was involved. Immunohistochemical results (S0048237–15): S-100 (−), P16 (partial+), CDK4 (partial+), MDM2 (−), Desmin (partial+), SMA (partial+), CD117 (+), CD34 (+), DOG-1 (+), SDHB (+), P53 (wild-type expression), Ki-67 (hot zone about 20 %+) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Postoperative specimen shows tumor size of approximately 19 cm × 16 cm × 11 cm.

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemistry reveals that the tumor is positive for CD34 (A), CD117(B), DOG-1(C) and SDHB(D).

Next-generation sequencing gene testing, also called high-throughput sequencing, showed that the patient has a non-frameshift mutation of exon 11 in the KIT gene and a missense mutation in exon 11 in the CHEK2 gene.

3. Discussion

GIST arises from the stomach, reaching a specific volume, often presented with abdominal pain, GI bleeding or palpable mass [8]. Unusually, this patient represented dizziness first. During emergency treatment, only then did he feel the presence of a lump in the upper right abdomen. Initial workup in patients with suspected GIST should include history and physical examination, complete blood cell counts, appropriate imaging of abdomen and pelvis using CT scan with contrast, endoscopy in selected cases of primary gastric or duodenal mass, and surgical assessment to determine tumor respectability and whether the metastatic disease affects this decision [9,10]. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans are essentially never required and should be reserved for research studies. Histologic confirmation is recommended but occasionally cannot be achieved [11]. Eventually, through the above series of measures and three-dimensional rebuilding of the enhanced CT scanning (Fig. 4), the patient obtained the correct preoperative diagnosis and the feasibility of radical surgery had also been confirmed.

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional rebuilding of the enhanced CT scanning shows clear demarcation between tumor (yellow zone) and biliary tract (green zone) and duodenum (purple zone). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Gastric GISTs have a better prognosis than small bowel or rectal GISTs. Furthermore, R0 resection, the mitotic rate, tumor size and tumor site are important prognostic factors. Distant metastasis, proliferation rate > 5 % and tumor rupture are additional adverse prognostic factors, the last should be recorded, regardless of whether it took place before or during surgery [12,13]. Giant GISTs can invade the adjacent organs from the origin of the tumor and have a high potential for distant metastases. Exceptionally, in this patient, the tumor only adhered to surrounding organs without invasion, although it was so huge. Maybe, the greater omentum tissue enveloped the tumor, thereby limiting its ability to spread. For large GISTs with no evidence of distant metastasis, surgery remains the crucial treatment of choice. [14] A partial gastrectomy was performed to remove the huge GIST en bloc.

The KIT mutations in different regions can affect the response to targeted therapy, providing guidance for choosing an appropriate agent with optimal dosage. For example, imatinib works better in tumors with exon 11 mutations than those with exon 9 mutations [2]. The KIT TKIs imatinib (first line), sunitinib (second line), regorafenib (third line), and ripretinib (fourth line) were approved by health authorities, such as the US Food and Drug Administration, based on studies in which eligibility required only a diagnosis of advanced GIST and no requirements of any particular molecular driver [15]. Our patient is under targeted therapy of imatinib according to NGS and guidelines. The recent follow-up results indicate a stable condition.

Li Fraumeni syndrome, also known as sarcoma, breast, leukemia, and adrenal gland (SBLA) syndrome, was first reported by Li and Fraumeni in 1969. LFS variants include LFS1, LFS2, LFSL. LFS1 is associated with mutations in TP53, a tumor suppressor gene. LFS2 is associated with mutations in CHEK2 (checkpoint kinase two), also a tumor suppressor gene [16]. To date, c.1100delC frameshift mutation in CHEK2 has been reported to be associated with LFS [17]. However, missense mutation rather than frameshift mutation is detected, and the patient cannot match the classic or chompret criteria for diagnosing this syndrome [18]. Thus, long-term follow-up and monitoring of patients is still required.

4. Conclusion

Although small size GISTs are usually asymptomatic and large size GISTs often present digestive system symptoms such as abdominal pain, GI bleeding and abdominal mass, GISTs with primary symptoms related to other systems also need to be identified carefully, especially in the emergency case. Systematic and comprehensive examination, including enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, three-dimensional rebuilding of the enhanced CT scanning, and even the biopsy, can be and should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and determine the feasibility of R0 resection, particularly when the tumor has a large volume and is suspected to be accompanied by local invasion or distant metastasis. What's more, it is clear that GIST is a complex tumor and requires effective integration of surgery and targeted therapy to reduce recurrence after resection of primary GIST or to prolong survival in metastatic disease.

Ethical approval

This study is exempt from ethnical approval in our institution, due to the number of cases is less than three.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

Study concept or design: Dongdong Zhang, Shuk Ying WONG, Jixiang Wu.

Data collection: Dongdong Zhang.

Writing the paper: Dongdong Zhang, Limin Guo, Shuk Ying WONG.

Guarantor

The guarantor is Dongdong Zhang.

Research registration number

None.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that there are no conflict interests.

References

- 1.von Mehren M., et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: gastrointestinal stromal tumors, version 2.2022: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines %J. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022;20(11):1204–1214. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu C.E., et al. Clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): from the molecular genetic point of view. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(5) doi: 10.3390/cancers11050679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechahougui H., Michael M., Friedlaender A. Precision oncology in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr. Oncol. 2023;30(5):4648–4662. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30050351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorour M.A., et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) related emergencies. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12(4):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koo D.H., et al. Asian consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016;48(4):1155–1166. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casali P.G., et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl. 4) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy320. p. iv267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhry U.I., DeMatteo R.P. Advances in the surgical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Adv. Surg. 2011;45:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballati A., et al. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor of stomach presenting with an intratumoral abscess: a case report. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2021;63 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poveda A., et al. GEIS 2013 guidelines for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST) Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;74(5):883–898. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2547-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demetri G.D., et al. NCCN Task Force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2010;8 Suppl 2(0 2):S1–41. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0116. (quiz S42-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer I.M., DeMatteo R.P., Serrano C. The GIST of advances in treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2022;42:1–15. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_351231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersting S., et al. GIST: correlation of risk classifications and outcome. J. Med. Life. 2022;15(8):932–943. doi: 10.25122/jml-2021-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmebakk T., et al. Definition and clinical significance of tumour rupture in gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the small intestine. Br. J. Surg. 2016;103(6):684–691. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeoh B.Z.Y., et al. Successful en bloc resection of complicated giant stomach gastrointestinal stromal tumor in an elderly patient. Am. J. Case Rep. 2022;23 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.934492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khosroyani H.M., Klug L.R., Heinrich M.C. TKI treatment sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Drugs. 2023;83(1):55–73. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01820-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aedma S.K., Kasi A. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies; 2023. Li-Fraumeni syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell D.W., et al. Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science. 1999;286(5449):2528–2531. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda Alcalde B., et al. The importance of Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a hereditary cancer predisposition disorder. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2021;119(1):e11–e17. doi: 10.5546/aap.2021.eng.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. (Lond. Engl.) 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]