Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alleviate pain and inflammation by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase pathway. This pathway has various downstream effects, some of which are beneficial. Prostaglandin E2 is a key downstream product in the cyclooxygenase pathway that modulates inflammation. A correlation between aging and increased expression of the prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP2, has been associated with inflammatory processes, cognitive aging, angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis. Therefore, inhibition of EP2 could lead to therapeutic effects and be more selective than inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2. Studies suggest that inhibition of EP2 restores age-associated spatial memory deficits and synaptic proteins and impairs tumorigenesis. The data indicate that EP2 signaling is important in myeloid cell metabolism and support its candidacy as a therapeutic target.

Key words: PGE2 signaling, EP2, prostaglandin E2, cognitive decline, tumorigenesis, myeloid metabolism, inflammation, cognition, COX

The cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway synthesizes prostanoids from the substrate arachidonic acid. These include prostaglandins PGH2, PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α, prostacyclin PGI2, and thromboxane TXA2. Studies suggest a positive correlation between the administration of COX-2 inhibitors and the reduction in certain cancers, cancer-related mortality, and neuroinflammation.1 Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a product of the COX-2 pathway and has been implicated in the process of inflammation, cognitive aging, angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis.1 Prostaglandin signaling occurs through 4 G-protein–coupled receptors: EP1, 2, 3, and 4.2 PGE2 signaling of the EP2 receptor leads to potentially beneficial or harmful effects that vary with the signaling components and the type of stimulus.1 PGE2-EP2 signaling may serve as a valuable therapeutic target given its presence and impact in inflammation, neurodegeneration, cytoprotection, tumorigenesis, and angiogenesis.

PGE2-Ep2 signaling pathways and components

It is crucial to recognize the components involved in PGE2-EP2 signaling to better understand the various downstream effects of this pathway. When stimulated by PGE2, the EP2 receptor mediates either a G protein–dependent response or a G protein–independent response. In the G protein–dependent pathway, EP2 functions as a stimulatory G (Gs) protein–coupled receptor that leads to adenyl cyclase activation and increased levels of cytoplasmic cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This results in the stimulation of either exchange protein directly acitvated by cAMP (Epac) or protein kinase A (PKA). Epac stimulation leads to the activation of Rap1/2, which is associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and injury. Conversely, PKA stimulation leads to the direct phosphorylation of the cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. The activation of cAMP-responsive element-binding is associated with beneficial effects such as neuroprotection, neuronal survival, enhanced memory, axonal growth, and axonal regeneration.3 Although cAMP preferentially stimulates PKA, the Epac pathway is stimulated under periods of sustained EP2 activation and higher levels of cAMP.1

The G protein–independent pathway occurs through β-arrestin and Src protein complex formation with the EP2 receptor. This complex interacts with epidermal growth factor receptors initiating pathways phosphoinositide 3-kinase/phosphokinase B (PKB/AKT), c-Jun-N-terminal kinase, and Ras/extracellular-signal–regulated kinase, which are involved in cell proliferation and metastasis.1 The G protein–dependent cAMP/PKA/cAMP-responsive element-binding and cAMP/Epac/Rap pathways undergo signaling crosstalk with the G protein–independent β-arrestin pathways. Specifically, recent reports have found agonists that prefer β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, which act to regulate the conformational states of the cytoplasmic region of E2 receptors, thus altering the function of the protein.4 Development of a G-protein–coupled receptor–biased ligand of the EP2 receptor would allow for selective stimulation of either G-protein–dependent or –independent signaling.

Inflammation and pain modulation

Myeloid cells, for example, macrophages and microglia, are responsible for initiating acute inflammation in response to injury by producing primary inflammatory mediators. These mediators, for example, histamine, bradykinin, and various chemokines and cytokines, are responsible for vasodilation and increased vascular permeability. Some inflammatory cytokines generated via the nuclear factor kappa B pathway lead to increased expression of COX-2, which increases synthesis of PGE2.5 PGE2, a secondary inflammatory mediator, further promotes vasodilation while attracting and activating immune cells, such as macrophages.

Prostaglandins have been implicated in the exacerbation of many different disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis through further activation of inflammation-related genes and cytokines. One report used collagen-induced arthritic mice to observe the interaction between PGI2-IP (prostaglandin receptor pathway) and IL-1β, in which the reduction of prostaglandin receptor I (IP) significantly reduced the extent of arthritis via synovial cell proliferation, bone destruction, and inflammatory cell proliferation.6 Important to note is that PGE2 is an immune modulator and its signaling via EP2 exacerbates inflammation.1 PGE2, in addition to being an immune modulator, amplifies sensitivity to pain, a process known as hyperalgesia. Mice genetically modified to lack EP2 receptors (EP−/−) and subsequently subjected to peripheral inflammation show a normal initial response without evidence of chronic hyperalgesia.7 Therefore, PGE2 may play a role in mediating chronic hyperalgesia through EP2.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly used in humans to alleviate pain and inflammation by inhibiting the entire COX-2 pathway. Studies have shown that the COX-2 pathway has some beneficial cardiovascular effects as seen in the mediation of late-phase ischemic preconditioning—a process in which short periods of ischemia lead to increased myocardial resistance, which furthers ischemia.8 Therefore, developing a selective EP2 inhibitor may be more beneficial to treat inflammation and preserve the beneficial effects of the COX-2 pathway. In addition, a selective EP2 inhibitor may have the potential to prevent pain in the setting of chronic hyperalgesia.

Tumorigenesis

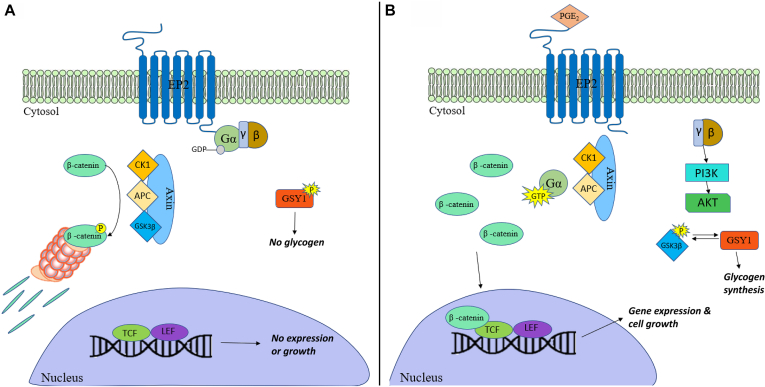

The EP2 receptor could be involved in tumorigenesis via multiple mechanisms, one of which is via the recruitment of β-arrestin 1. As previously mentioned, β-arrestin leads to the activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and Ras/extracellular-signal–regulated kinase pathways through a G protein–independent manner by complexing with Src and epidermal growth factor receptors.9 Both pathways promote cellular proliferation and metastasis. Cross talk between the G protein–independent and –dependent pathway can also lead to activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway by Gβγ subunit release on EP2 receptor activation. This could lead to inhibitory phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (Fig 1), subsequently resulting in the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and thereby stimulate growth-promoting gene expression.10

Fig 1.

G-protein–dependent signaling via β-catenin. A, Without the presence of an agonist for EP2, G-proteins remain inactive and β-catenin is phosphorylated and picked up by a nucleosome for destruction. At the same time, glycogen synthase I remains inactive and no glycogen is produced. B, The presence of PGE2 activates the αs guanosine triphosphate (GTP) subunit and releases β-catenin and GSK-3β from Axin. During this time, the free βγ subunits activate the PI3K-PDK1-AKT signaling pathway, resulting in the inhibitory phosphorylation of the free GSK-3β. GYS1 is then enabled to conduct glycogen synthesis without inhibition from GSK-3β. Without GSK-3β to inhibit it, the released β-catenin is allowed to undergo nuclear translocation, promoting gene expression and cell growth. AKT, Protein kinase B; APC, Adenomatous polyposis coli protein; CK1, casein kinase 1; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; GYS1, glycogen synthase 1; LEF, lymphoid enchancer factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; TCF, T-cell factor.

The role of EP2 receptor signaling in chronic inflammation may account for its role in tumorigenesis, given the established relationship between chronic inflammation and the local microenvironment—which is conducive to tumor formation and genetic alterations. The proinflammatory mediators associated with PGE2-EP2 signaling, for example, chemokines and cytokines, provide a foundation for angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Likewise, EP2 signaling modulates immune cells through the downregulation of INF-γ and TNF-α expression, thus impairing their ability to regulate apoptosis and prevent tumorigenesis.1 Another interesting observation is that EP2 signaling converts TGF-β through the alteration of TGF-β signaling from a tumor-suppressing to a tumor-promoting agent.1

There is a probable connection between EP2 signaling and tumorigenesis as demonstrated in in vivo mouse models. The lack of EP2 receptors is associated with a reduction in both the size and number of intestinal polyps in EP2−/− mice with familial adenomatous polyposis. The deletion of EP2 receptors in this same model reduced tumor growth and led to increased life expectancy. Similarly, mice that underwent ablation of the EP2 receptor revealed a reduction in skin tumor development, whereas overexpression showed enhanced skin tumor development.1 Administration of the EP2 agonist, butaprost, in multiple mouse models of prostate cancer suggests that EP2 receptor signaling leads to promotion of tumor growth and invasion.11 Treating mice with the EP2 antagonist, TG4-155, inhibits EP2 signaling and leads to a reduction in prostatic growth and invasion.11 Similarly, TG6-10-1, an analog of TG4-155 with an improved in vivo half-life and brain penetration, has been shown to impair malignant glioma growth by reducing COX-2 activity–driven glioblastoma multiforme cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis.12 Furthermore, it was found that EP2 antagonism by TG6-10-1 led to an arrest in the cell cycle at G0-G1 and resulted in apoptosis of glioblastoma multiforme cells.12 These findings all provide insight into how a selective EP2 receptor antagonist could reduce tumorigenesis, possibly through the modulation of inflammation and angiogenesis.

Metabolic bioenergetic implications

PGE2-EP2 signaling is implicated as a significant contributor for cognitive decline. With age, levels of PGE2 increase, so too does the expression of EP2 receptors on human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs).13 As shown in Fig 1, the incidence of PGE2-EP2 signaling activates glycogen synthase 1 from the phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β via protein kinase B (PKB/AKT). This results in glycogen synthesis, which is associated with a decrease in glucose utilization in glycolysis or the pentose phosphate pathway. PGE2 signaling leads to decreases in glycolysis and a reduction in the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate as shown through PGE2 stimulation within human MDMs.13 These decreases are mediated by the EP2 receptor. Therefore, in aged human MDMs, PGE2 signaling with EP2 may be closely associated with the promotion of glucose sequestration into glycogen. This could lead to reduced glucose flux and mitochondrial respiration.13

Cellular metabolism is an integral component in the regulation and function of the immune system.14 If the bioenergetics of a cell could be compromised, it serves as a potential route to develop maladaptive phenotypes, some of which are typically attributed to aging. PGE2 may hinder human MDM function over time. In older macrophages, there is increased activity of PGE2, EP2, and glycogen synthase, all of which enhance the conversion of glucose into glycogen. This diminishes glucose flux, reducing readily available energy. In addition, findings suggest that metabolic transitions occur in aging myeloid cells that cause them to be unable to use alternative energy resources. Minhas et al13 labeled human MDMs with 13C-isotopes of glutamine, pyruvate, lactate, and glucose and found that aged human MDMs are metabolically dependent on glucose.13 Conversely, they also showed that young human MDMs are more capable of converting glucose, pyruvate, lactate, and glutamine into glycolytic and TCA-cycle intermediates.13 Because of the dependence of aged human MDMs on glucose, PGE2-EP2 signaling could result in a bioenergetically deficient state. Previous research has indicated that energy metabolism in the cell plays a key role in the regulation of the immune system; specifically, activated T cells engage primarily in glycolysis, fixing pyruvate as lactate to restore nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and perpetuate glycolysis.15 Without glycolysis, T cells, MDMs, and other similar cell types would be unable to produce the energy required to properly function, thus inducing a proinflammatory response such as that of aged human MDMs.

Another possible consequence of this bioenergetic deficiency involves cognitive decline. In the human brain, the microglial cells compose the main myeloid population and, with age, show an increased expression of EP2.16 The EP2 receptor, implicated in both in vitro and in vivo mouse models, promotes chronic neuroinflammation.1 Aged myeloid cells, in an energy-deficient state, promote proinflammatory cytokine expression. Chronic inflammation may result in cognitive impairments, such as spatial memory deficits, commonly attributed to age. Alzheimer disease is a prominent pathology involving cognitive impairment. Within these brains, there are abnormal levels of amyloid-beta plaques, which play an integral role in this disease. Compound 52 (C52) is a brain-penetrant EP2 inhibitor. In an ex vivo assay of mice treated with C52, the treated mice demonstrated an increased macrophage-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta plaques.17 This suggests a possible route through which EP2 inhibition may improve cognition. Additional studies should be conducted to evaluate whether similar results can be produced in an in vivo model and its effect on cognition.

EP2 receptors as a therapeutic target

Minhas et al hypothesized that either the reduced expression or selective inhibition of the EP2 receptor would alleviate the bioenergetic insufficiency experienced by aged myeloid cells. For example, genetic reduction of the EP2 receptor by 50% in mice (Cd11bCrelox/lox) leads to increased mitochondrial respiration and increased glycolysis, and restored mitochondrial morphology.13 When aged Cd11bCrelox/lox mice performed tasks to evaluate spatial memory and cognition, their performance was indistinguishable from that of younger Cd11bCrelox/lox mice; however, aged Cd11bCrelox/lox mice significantly outperformed aged mice that had not undergone the knockdown of EP2 receptors.6 This suggests that there is a relationship between the metabolism of aging MDMs and cognitive decline. Treating mice with the EP2 inhibitors, PF-04418948 and C52, inhibits PGE2-EP2 signaling and results in increased energy production within aged myeloid cells. This reduces glycogen synthesis and enhances glycolytic and TCA-cycle activities, as seen in the Cd11bCrelox/lox mice models.6

Inflammatory factors in plasma and the hippocampus were restored to levels comparable to those in their youthful counterparts after treating mice for 1 month with the brain-penetrant EP2 inhibitor C52.6 C52-treated mice cognition was evaluated with an object location memory test and the Barnes maze task, which revealed an improvement in age-associated memory deficits compared with controls.6 Electrophysiological recordings of the aged mice treated with C52 showed a restoration of hippocampal CA1 long-term potentiation, a mechanism responsible for learning and memory; in addition, this result was seen in Cd11bCrelox/lox mice.6 When mice were treated peripherally with the brain-nonpenetrant EP2 inhibitor, PF-04418948, for 6 weeks, they exhibited similar benefits to those treated with the brain-penetrant C52 and to Cd11bCrelox/lox mice.6

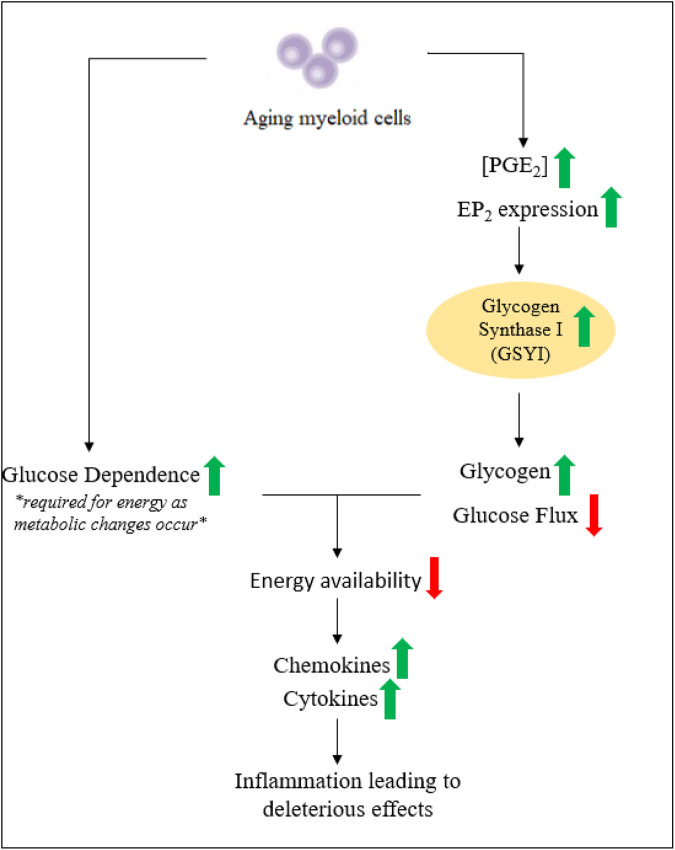

Restoration of hippocampal plasticity and memory function, associated with the reduction of EP2 signaling, indicates that MDM metabolism correlates with cognitive function. This association implies that at least 2 mechanisms converge, leading to cognitive deficits associated with aging. As MDMs age, their metabolism shifts toward glucose dependence and when combined with an increase in PGE2 signaling, a bioenergetic-deficient state occurs (Fig 2). This results in the age-associated mitochondrial abnormalities in morphology, number, and density. These changes also promote the circulation of proinflammatory factors that cause cognitive decline. These metabolic changes may also promote angiogenesis, tumorigenesis, and cellular proliferation. However, the findings of Minhas et al show that downregulation or inhibition of PGE2-EP2 signaling reverses bioenergetic dependence on glucose, improves mitochondrial morphology, restores synaptic proteins, and ultimately reverses age-associated spatial memory deficits (Fig 3).13

Fig 2.

Two mechanisms converge, leading to bioenergetic insufficiency in myeloid cells. In aging myeloid cells, levels of PGE2 and EP2 are markedly increased. This increase leads to increased EP2 signaling, which subsequently leads to the activation of glycogen synthase 1 (GYS1), which decreases glucose flux. This culminates with metabolic changes in which myeloid cells become dependent on glucose energetically, resulting in a bioenergetics-deficient state. This bioenergetic state leads to the accumulation of proinflammatory mediators and harmful effects.

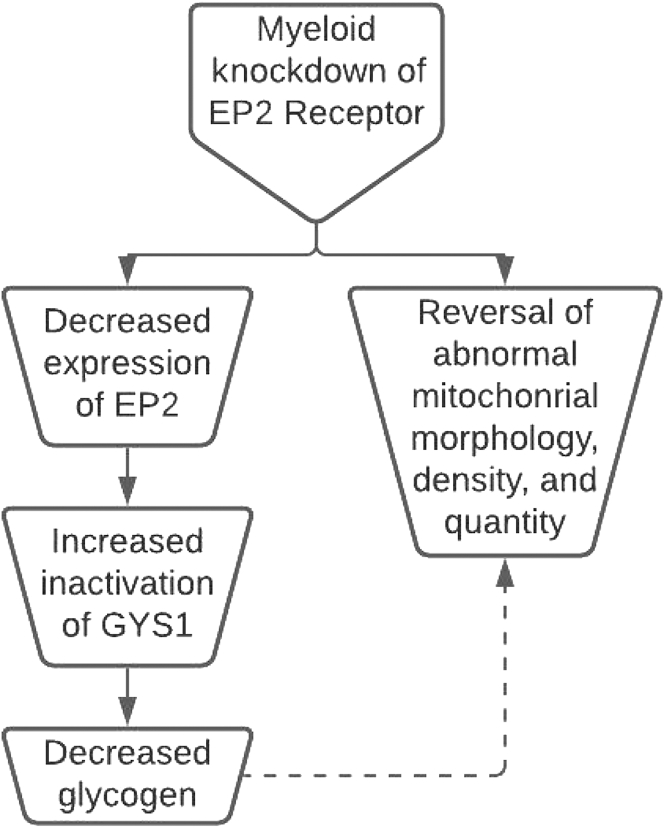

Fig 3.

Myeloid knockdown of the EP2 receptor provides significant insight. The study conducted by Minhas et al using Cd11bCrelox/lox mice showed the effects of reducing EP2 expression by 50%.13 Notable impacts were the reduction in glycogen synthase 1 and the subsequent reduction in glycogen synthesis. Remarkably, physiological abnormalities observed within mitochondria associated with age reversed, indicating there is a connection between EP2 signaling and abnormalities in mitochondrial density, number, and morphology. GYS1, Glycogen synthase 1.

New perspectives and concluding remarks

Two major converging mechanisms, within aging myeloid cells, contribute to the cellular energy metabolism: the significant increase in proinflammatory PGE2 signaling that occurs and their inability to use alternative energy resources (Fig 2). The mechanisms directly connecting MDM metabolism to cognitive function remain to be elucidated. One hypothesis is that the suppression of the electron transport chain leads to increased levels of succinate and activation of the expression of proinflammatory cytokines.6 Another is that the deleterious effects of the EP2 pathway may be due to the production of free radicals. Costantino Iadecola of Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, affirms this, stating: “The relative contribution of free radicals versus metabolic dysfunction should be addressed in future work.”16 In the past, free radical production has been noted to be a contributing factor in many aging-related conditions.16 Knowing whether EP2 signaling is a contributing factor could help provide a clearer relationship between its signaling and effects. An important consideration is the need to identify the factors responsible for the metabolic dependence on glucose attributed to aged MDMs. This may be a valuable target to research, because defining this process may provide new techniques to improve MDM bioenergetics.

A question remains to be addressed: does PGE2-EP2 signaling ultimately result in the promotion of inflammation, leading to further increases in PGE2 levels and EP2 receptor expression? If so, it may explain why there are notable increases in PGE2 levels and expression of EP2 receptors within aged myeloid cells. PGE2-EP2 signaling may exacerbate bioenergetic insufficiency and promote inflammation, given the established metabolic susceptibility of aged myeloid cells. This inflammation may lead to increased PGE2 production and expression of EP2 receptors over time. Development of a selective EP2 inhibitor could break this cycle.

Another facet to explore is the connection between myeloid metabolism, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Inhibition of EP2 signaling prevents the formation, growth, and invasion of certain tumors, but the mechanisms remain unknown. It is hypothesized that the bioenergetic insufficiency by aging myeloid cells contributes to tumor formation by permitting developing tumors to avoid immunosurveillance due to impaired immune function. Future studies should evaluate the mechanisms by which EP2 inhibition leads to the prevention of tumorigenesis, whether MDM metabolism is interconnected, and how inflammation plays a role. There is novel interest in the intracellular complex, the inflammasome. The inflammasome generates cytokine IL-1β, responsible for triggering an inflammatory cascade.18 Knowing whether there is a connection between the metabolic processes of aging myeloid cells and inflammasome activation could lead to an understanding of the inflammatory processes involved in cognitive decline.

Considering the potential therapeutic benefits that may be derived from EP2 inhibition, evaluating adverse effects and the long-term impacts of such therapy should always be considered within any human trials. The experiments with C52 and PF-04418948 have since been discontinued.15 Amgen’s C52 only has been tested in preclinical rodent trials and is not being further developed for clinical use. Development of Pfizer’s PF-04418948 was discontinued without published results following a phase 1 safety study. The clinical trial of PF-04418948 is significant because it is the only EP2 antagonist to have been tested in humans to date. It is worth reemphasizing that PF-04418948 cannot cross the blood-brain barrier and possibly limits its potential to treat cognitive decline.6 However, a potent, selective, and safe EP2 inhibitor remains a target for future pharmacologic development. It may be a useful alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which block COX-1 and all its downstream effects, some of which are beneficial. An EP2 inhibitor may provide new strategies for both cancer and anti-inflammatory therapy. Likewise, inhibition of EP2 could reduce the risk of cellular proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, common with tumorigenesis.

The data provide interesting perspectives in the restoration of myeloid metabolism and reversal of cognitive deficits. This leads to another hypothesis: cognitive aging and tumorigenesis may be associated with metabolic changes within myeloid cells. It is possible to reverse the cognitive declines associated with these metabolic changes. EP2 inhibition reprograms myeloid glucose metabolism and subsequently restores immune function. These findings support the idea that there is plasticity to the process of cognitive aging and allows us to consider aging as a reversible process. New strategies to reverse aging could include pharmaceuticals designed to restore cellular metabolism that also contribute to cognition. One such pharmaceutical could potentially be a potent, safe, and selective EP2 inhibitor.

Footnotes

N.K. was funded by the American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant (grant no. 09SDG2260957), National Institutes of HealthNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant no. R01 HL-105932), and the Joy McCann Culverhouse endowment to the Division of Allergy and Immunology.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Jiang J., Dingledine R. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the crosshairs of anti-inflammation, anti-cancer, and neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breyer R.M., Bagdassarian C.K., Myers S.A., Breyer M.D. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barco A., Kandel E.R. Verlag GmbH & Co; 2005. The role of CREB and CBP in brain function. In: Transcription factors in the nervous system; Wiley-VCH; pp. 206–241. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J.J., Horst R., Katritch V., Stevens R.C., Wüthrich K. Biased signaling pathways in β2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science. 2012;335:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee K.M., Kang B.S., Lee H.L., Son S.J., Hwang S.H., Kim D.S., et al. Spinal NF-kB activation induces COX-2 upregulation and contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3375–3381. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda T., Segi-Nishida E., Miyachi Y., Narumiya S. Prostacyclin-IP signaling and prostaglandin E2-EP2/EP4 signaling both mediate joint inflammation in mouse collagen-induced arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:325–335. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinold H., Ahmadi S., Depner U.B., Layh B., Heindl C., Hamza M., et al. Spinal inflammatory hyperalgesia is mediated by prostaglandin E receptors of the EP2 subtype. J Clin Investig. 2005;115:673–679. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolli R., Shinmura K., Tang X.-L., Kodani E., Xuan Y.-T., Guo Y., et al. Discovery of a new function of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2: COX-2 is a cardioprotective protein that alleviates ischemia/reperfusion injury and mediates the late phase of preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:506–519. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00414-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa S., Watanabe T., Sugimoto I., Moriyuki K., Goto Y., Yamane S., et al. Discovery of G protein-biased EP2 receptor agonists. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7:306–311. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellone M.D., Teramoto H., Williams B.O., Druey K.M., Gutkind J.S. Prostaglandin E2 promotes colon cancer cell growth through a Gs-axin-beta-catenin signaling axis. Science. 2005;310:1504–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J., Dingledine R. Role of prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the regulations of cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:360–367. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.200444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu J., Li Q., Bell K.A., Yao X., Du Y., Zhang E., et al. Small-molecule inhibition of prostaglandin E receptor 2 impairs cyclooxygenase-associated malignant glioma growth. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:1680–1699. doi: 10.1111/bph.14622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minhas P.S., Latif-Hernandez A., McReynolds M.R., Durairaj A.S., Wang Q., Rubin A., et al. Restoring metabolism of myeloid cells reverses cognitive decline in ageing. Nature. 2021;590:122–128. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills E.L., Kelly B., O’Neill L.A.J. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of immunity. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:488–498. doi: 10.1038/ni.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce E.L., Pearce E.J. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity. 2013;38:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers MB. Myeloid metabolic crisis may trigger cognitive decline in aging brain: alzforum. Available at: https://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/myeloid-metabolic-crisis-may-trigger-cognitive-decline-aging-brain. Accessed October 20, 2022.

- 17.Fox B.M., Beck H.P., Roveto P.M., Kayser F., Cheng Q., Dou H., et al. A selective prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2 (EP2) antagonist increases the macrophage-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta plaques. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5256–5273. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorman R.M. Pharma looks to inflammasome inhibitors as all-around therapies. TheScientist. April 1, 2021 [Google Scholar]