Abstract

Candida dubliniensis has been associated with oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). C. dubliniensis isolates may have been improperly characterized as atypical Candida albicans due to the phenotypic similarity between the two species. Prospective screening of oral rinses from 63 HIV-infected patients detected atypical dark green isolates on CHROMagar Candida compared to typical C. albicans isolates, which are light green. Forty-eight atypical isolates and three control strains were characterized by germ tube formation, differential growth at 37, 42, and 45°C, identification by API 20C, fluorescence, chlamydoconidium production, and fingerprinting by Ca3 probe DNA hybridization patterns. All isolates were germ tube positive. Very poor or no growth occurred at 42°C with 22 of 51 isolates. All 22 poorly growing isolates at 42°C and one isolate with growth at 42°C showed weak hybridization of the Ca3 probe with genomic DNA, consistent with C. dubliniensis identification. No C. dubliniensis isolate but only 18 of 28 C. albicans isolates grew at 45°C. Other phenotypic or morphologic tests were less reliable in differentiating C. dubliniensis from C. albicans. Antifungal susceptibility testing showed fluconazole MICs ranging from ≤0.125 to 64 μg/ml. Two isolates were resistant to fluconazole (MIC, 64 μg/ml) and one strain was dose dependent susceptible (MIC, 16 μg/ml). MICs of other azoles, including voriconazole, itraconazole, and SCH 56592, for these isolates were lower. C. dubliniensis was identified in 11 of 63 (17%) serially evaluated patients. Variability in phenotypic characteristics dictates the use of molecular and biochemical techniques to identify C. dubliniensis. This study identifies C. dubliniensis in HIV-infected patients from San Antonio, Tex., and shows that C. dubliniensis is frequently detected in those patients by using a primary CHROMagar screen.

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) continues to be a common opportunistic infection in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or who have AIDS (8–11). Candida albicans is the most common causative agent; however, other species, such as C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei have become increasingly prominent pathogens (10–12, 19). A recently described species, C. dubliniensis, has been associated with the presence of OPC in HIV-infected patients and has also been recovered from healthy, non-HIV-infected patients (1, 16–18). C. dubliniensis has been reported from patients worldwide (17) including the United States (13), but the prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of this species in patients from the United States has not been reported.

C. dubliniensis is closely related to C. albicans, and many C. dubliniensis isolates may have been improperly characterized as atypical C. albicans due to the phenotypic similarity of the two species (4, 15, 16). For example, both species produce germ tubes and chlamydoconidia, typically used to identify C. albicans. Variation in the ability to differentiate the two species by using phenotypic characteristics has led researchers to investigate more reliable methods for proper differentiation of these isolates (15, 17) and dictates the use of a combination of mycological, biochemical, and molecular techniques to unequivocally identify C. dubliniensis (2, 7, 13, 16, 18).

C. dubliniensis has been reported to produce a distinctive dark green color on CHROMagar Candida (15). However, this atypical color may not persist after serial passage of the organism and may be less useful for identifying isolates (16). In the present study, atypical yeast isolates were prospectively identified by serial evaluation of primary CHROMagar Candida cultures from HIV-infected patients with OPC in San Antonio, Tex. These atypical isolates were then screened for C. dubliniensis by using phenotypic and genotypic assays, and the identification and prevalence of C. dubliniensis in this population was established.

Little information is available on susceptibility patterns of clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis. Fluconazole susceptibility testing by a modified microbroth dilution method on 20 C. dubliniensis isolates, including 15 oral isolates from HIV-infected patients, demonstrated MICs ranging from ≤1 to 32 μg/ml, with MICs of ≤1 μg/ml being determined for 80% of isolates tested (4). In this study antifungal susceptibilities to amphotericin B and four azole agents were tested for one C. dubliniensis type strain and 22 clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis from HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis.

(This study was presented in part at the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Atlanta, Ga., 17 to 21 May 1998 [abstract F48].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection.

Clinical samples were obtained from HIV-infected patients enrolled in a longitudinal study of OPC at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, Audie L. Murphy Division, San Antonio, Tex. (9, 10). These patients had advanced AIDS with mean CD4 cell counts of <50/mm3. Samples were obtained weekly during therapy and quarterly as surveillance cultures by patients swishing and spitting 10 ml of normal saline to be used for culture (6, 9). One-hundred microliters of swish solution was plated on media with and without fluconazole at concentrations of 8 and 16 μg/ml and incubated at 30°C for 48 h before growth was assessed. CHROMagar Candida (CHROMagar Company, Paris, France) with fluconazole was used to improve detection of non-C. albicans species and resistant isolates (6). Colonies with a light-green color on CHROMagar Candida were considered typical C. albicans, whereas those with a dark-green color were considered atypical C. albicans (10, 11). Isolate color was recorded, and three to five yeast colonies from each culture were stored on Sabouraud dextrose slants (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) at −70°C. Forty-eight atypical clinical isolates from 23 patients were detected and were further characterized by phenotypic and genotypic identification tests.

Reference strains.

Three control strains, including the C. albicans reference strain 3153A, generously provided by D. R. Soll (University of Iowa, Iowa City, Ia), the C. dubliniensis type strain NCPF 3949, kindly provided by J. R. Naglik (UMDS Guy’s Hospital, London, England), and a laboratory control strain, fluconazole-resistant C. albicans 279, were included in this study.

Phenotypic identification tests.

All dark green atypical C. albicans isolates were further characterized by analysis of germ tube formation in human serum at 37°C for 3 h, growth at 37, 42, and 45°C on Sabouraud dextrose agar (BBL), identification by API 20C (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France), fluorescence on methyl-blue 93 Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with illumination at 365 nm, and degree of chlamydoconidium production on cornmeal agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 1% Tween 80 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Genotypic identification tests.

Organism identification was further investigated by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and DNA fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive Ca3 probe, which as previously described is specific for C. albicans (14). Chromosomal DNA from each isolate was prepared in agarose plugs and separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was performed using ramped switch times of 5 to 35 s for 18 h at 3 V/cm. RFLP patterns were obtained by digestion of chromosomal DNA with EcoRI (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Digested DNA present in the RFLP gels was transferred to nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.) and hybridized under stringent conditions with a Ca3 probe radioactively labeled by random priming (Random Primers DNA Labeling System; GibcoBRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) (14). After being washed, the membranes were exposed to autoradiography film (Du Pont, Wilmington, Del.). Films were scanned and imported to Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, Calif.).

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing was performed according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards macrobroth method M27-A (5). Inocula were standardized at 85% transmittance at 530 nm by using a spectrophotometer. Antibiotic medium 3 (Difco Laboratories) was used for testing amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.) (0.03 to 16 μg/ml), and RPMI-1640 buffered with morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (American Biorganics, Niagara Falls, N.Y.) was used for testing fluconazole (Pfizer, Inc., New York, N.Y.) (0.125 to 64 μg/ml), itraconazole (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) (0.015 to 16 μg/ml), voriconazole (Pfizer, Inc., Sandwich, United Kingdom) (0.125 to 64 μg/ml), and SCH 56592 (Schering Plough, Kenilworth, N.J.) (0.03 to 16 μg/ml). Amphotericin B and fluconazole were prepared from pharmaceutical solutions in sterile water. Itraconazole, voriconazole, and SCH 56592 were prepared from powder to stock solutions of 1,600 μg/ml in 100% polyethylene glycol. Tubes were incubated at 35°C and read at 24 and 48 h.

RESULTS

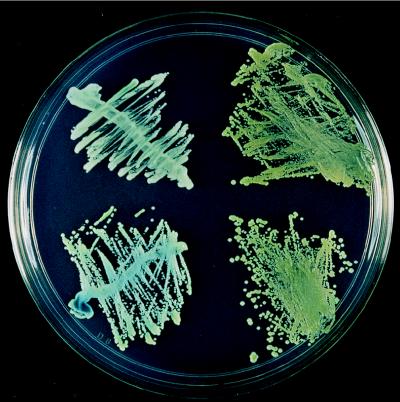

Twenty-three of 63 (37%) HIV-infected patients had atypical, dark green colonies on CHROMagar Candida in 48 episodes of OPC. Colonies with light green color (Fig. 1, left side of plate) were considered typical for C. albicans, whereas those with a dark green color on primary isolation were initially considered atypical C. albicans (Fig. 1, right side of plate) and were subjected to further investigation.

FIG. 1.

Color comparison of typical C. albicans (left) and atypical C. albicans (right) on CHROMagar Candida following 48 h of incubation at 30°C.

Results of other phenotypic and genotypic identification assays are shown in Table 1. All isolates produced germ tubes. Abundant chlamydoconidium production was seen in only 17 of 51 (33%) isolates. Overall, of the isolates ultimately identified as C. dubliniensis (see below), 16 of 23 (70%) had abundant chlamydoconidium production, indicative of C. dubliniensis, while only 1 of 28 (4%) of those identified as C. albicans had abundant chlamydoconidium production (Table 1). With API 20C, 25 of 28 (89%) C. albicans isolates were identified as C. albicans, while 8 of 23 (35%) C. dubliniensis isolates were misidentified as C. albicans (Table 1). Xylose utilization was negative in all 23 isolates identified as C. dubliniensis and was positive in all 28 C. albicans strains. A total of 42 of 51 (82%) isolates were positive for fluorescence (with illumination at 365 nm) on methyl-blue 93 Sabouraud dextrose agar. Fluorescence was seen in 25 of 28 (89%) C. albicans isolates and in 17 of 23 (74%) C. dubliniensis isolates (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of clinical isolates identified as atypical C. albicans upon primary isolation on CHROMagar Candidaa

| Isolate no. | Chlamydoconidium formation | API-20C identification | Xylose utilization | Fluorescence on methyl-blue (18 h) | Growth after 72 h at:

|

Ca3 probe hybridizationb | Identification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37°C | 42°C | 45°C | |||||||

| 903 | + | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1029 | − | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1154 | + | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1231 | + | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1232 | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1439 | + | No ID | − | − | − | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1478 | − | No ID | − | + | + | + | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1680 | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1721 | − | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1770 | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 1869 | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 2419 | + | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 2696 | − | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 2929 | − | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3163 | + | No ID | − | − | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3418 | + | No ID | − | − | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3698 | + | No ID | − | − | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3744 | − | No ID | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3949c | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 3973 | − | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 4516 | + | C. albicans | − | + | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 4572 | + | No ID | − | − | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 4712 | + | No ID | − | − | + | − | − | Poor | C. dubliniensis |

| 279c | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 1019 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 1582 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 1593 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 1683 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 2144 | − | No ID | + | − | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 2579 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 2759 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 3153Ac | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 3505 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 3510 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 3748 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 3777 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 3786 | − | No ID | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4016 | − | No ID | + | − | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 4077 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4105 | + | C. albicans | + | − | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4221 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4350 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4369 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4372 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4413 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4487 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | − | Good | C. albicans |

| 4665 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4667 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4724 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4730 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

| 4812 | − | C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | Good | C. albicans |

“+” and “−” indicate presence or absence of characteristic, respectively, except in the case for growth at 72 h, where such symbols indicate normal and none to slight, respectively.

Poor Ca3 probe hybridization is consistent with C. dubliniensis identification; good Ca3 probe hybridization is consistent with C. albicans identification.

Lab control strain.

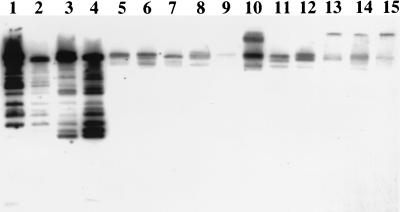

Differential temperature growth is shown in Table 1. Fifty of 51 (98%) isolates grew well at 37°C. Very poor or no growth occurred at 42 and 45°C in 22 of 51 (43%) and 33 of 51 (65%) isolates, respectively. One isolate grew poorly at all temperature settings. Twenty-eight of 29 (97%) isolates that grew well at 42°C showed good hybridization of the moderately repetitive Ca3 probe with genomic DNA, indicative of C. albicans (Fig. 2). All 22 isolates with negligible growth at 42°C and 1 strain with growth at 42°C showed weak hybridization of genomic DNA with the Ca3 probe, consistent with C. dubliniensis identification. All 23 C. dubliniensis strains demonstrated negligible or no growth at 45°C, but growth was seen in only 18 of 28 (64%) C. albicans isolates.

FIG. 2.

Southern hybridization fingerprinting of restriction endonuclease EcoRI-digested whole-cell DNA with 32P-labeled moderately repetitive Ca3 probe. Fingerprinting patterns of C. albicans reference strains 3153A and 279 (lanes 1 and 2), C. dubliniensis reference strain 3949 (lane 8), clinical isolates 1683, 4413, 1680, 1770, and 4516 (lanes 3 to 7, respectively) and clinical isolates 1439, 2419, 1231, 2696, 3163, 1154, 1478 (lanes 9 to 15, respectively) are shown. Lanes 3 and 4 show hybridization patterns typical of C. albicans; lanes 5 to 7 and 9 to 15 show poor hybridization patterns characteristic of C. dubliniensis.

Overall, 22 clinical C. dubliniensis isolates were identified from 11 of 63 (17%) serially evaluated patients. C. dubliniensis was associated with infection in 16 of 22 episodes but was detected on surveillance cultures from the remaining 6 episodes. Isolation occurred after 2.9 ± 0.2 episodes (mean ± standard error; range, 1 to 8), although isolation occurred in the initial episode for five patients. Isolation of C. dubliniensis occurred in mixed yeast cultures including C. albicans and other yeasts in 11 of 22 (50%) cases (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antifungal susceptibility of C. dubliniensis isolates from HIV-infected patients

| Patient | Isolate | MICs of the following compound at 24/48 h (μg/ml):

|

No. of OPC episodes | Prior fluconazole treatment (g) | Other species present | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | Fluconazole | Itraconazole | Voriconazole | SCH 56592 | |||||

| 2 | 1029 | .125/.25 | .25/.5 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | 2 | 0.7 | C. albicans |

| 2 | 1231 | .06/.25 | .25/.5 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | Surveillancea | 1.4 | None |

| 2 | 1232 | .125/.125 | 1/2 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | Surveillance | 1.4 | None |

| 9 | 1439 | .25/.25 | 1/1 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .125/.125 | 4 | 3.5 | None |

| 21 | 903 | .125/.25 | ≤.125/.≤.125 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/.06 | 1 | 0.7 | C. glabrata |

| 26 | 1154 | .125/.25 | 1/2 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .25/.25 | 1 | None | C. albicans |

| 32 | 1680 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | .03/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | 2 | 2.1 | None |

| 32 | 1721 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/1 | .06/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | 2 | 3.5 | None |

| 32 | 1869 | .125/.125 | ≤.125/.5 | .06/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | 3 | 4.9 | None |

| 36 | 1478 | .25/.5 | .25/.5 | .06/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .125/.25 | 1 | None | None |

| 46 | 1770 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | 1 | 0.7 | C. krusei |

| 46 | 2419 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | ≤.015/≤.015 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/.06 | 4 | 2.8 | C. krusei |

| 46 | 3744 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | .03/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .125/.125 | Surveillance | 1.4 | C. krusei |

| 46 | 3973 | ≤.03/.125 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .125/.125 | 8 | 24.2 | C. krusei |

| 59 | 4572 | ≤.03/.125 | 32/64 | .5/.5 | 1/1 | .125/.25 | 6 | 10 | None |

| 60 | 2696 | .06/.25 | .25/.5 | .03/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .06/.25 | 1 | None | None |

| 60 | 3163 | .06/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .016/.125 | 4 | 3 | None |

| 60 | 3418 | .06/.125 | .25/.5 | .03/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | .125/.25 | 5 | 3.8 | None |

| 61 | 2929 | .06/.125 | .25/1 | ≤.015/.03 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/.125 | 2 | 2.3 | C. krusei |

| 64 | 3698 | ≤.03/.125 | 16/16 | .125/.25 | .25/.5 | .25/.5 | Surveillance | 3.2 | C. glabrata |

| 64 | 4516 | ≤.03/.125 | 4/4 | .03/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | ≤.03/≤.03 | Surveillance | 11.2 | C. glabrata |

| 64 | 4712 | .06/.125 | 32/64 | .5/1 | 1/2 | .125/.25 | Surveillance | 12 | C. glabrata |

| 3949b | .06/.125 | ≤.125/.25 | .06/.06 | ≤.125/≤.125 | ≤.03/≤.03 | ||||

Surveillance culture was used.

Lab strain.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed on the 22 isolates plus a C. dubliniensis type strain according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method M-27A with amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and SCH 56592 (Table 2). Isolates were all susceptible to amphotericin B, with the MIC for 16 of 23 isolates being 0.125 μg/ml (range 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml) at 48 h. The azoles demonstrated a wide range of MICs. Fluconazole MICs ranged from ≤0.125 to 64 μg/ml. The results for the other azoles were as follows: SCH 56592, MICs of ≤0.03 to 0.5 μg/ml; itraconazole, MICs of ≤0.03 to 1 μg/ml; and voriconazole, MICs of ≤0.125 to 2 μg/ml. Two isolates were resistant to fluconazole (MICs of 64 μg/ml at 48 h), and one showed dose-dependent susceptibility (MIC = 16 μg/ml). MICs of the other azoles for these isolates were lower: SCH 56592, MICs of 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml; itraconazole, MICs of 0.25 to 1 μg/ml; and voriconazole, MICs of 0.5 to 2 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

Although C. dubliniensis has been reported in association with oropharyngeal infection from patients in the United States (13), the prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of C. dubliniensis from patients in the United States has not been reported. In this study, the detection and prevalence of C. dubliniensis was established in a cohort of patients from San Antonio, Tex., with recurrent OPC and advanced AIDS who were serially evaluated. The prevalence of C. dubliniensis in this population was similar to that reported in HIV-infected patients in Ireland (32%) and confirms the widespread geographic distribution of this species (1, 17). However, it should be noted that the 22 clinical C. dubliniensis isolates identified in this study represent <1% of the more than 5,500 isolates collected from these 63 patients in this ongoing serial evaluation (9, 10), suggesting that these isolates appear to remain uncommon in HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal infection.

Isolates were screened for further study by selecting for atypical, dark green color on primary CHROMagar Candida cultures. Variable results using CHROMagar Candida to identify C. dubliniensis have been reported (15, 16), which may be due to the fact that color may vary after serial passage. In this study, 22 of 48 (46%) clinical isolates initially considered to be atypical C. albicans were subsequently identified as C. dubliniensis. Since only atypical C. albicans isolates were screened for this study, it is possible that the reported prevalence could be an underestimate of the true prevalence in this population. However, more than 50 typical light green CHROMagar Candida isolates were confirmed to be C. albicans by phenotypic assays and the Ca3 probe in other studies (data not shown). These results suggest that primary isolation of atypical C. albicans colonies on chromogenic media could be used as a screening assay for additional identification studies.

Phenotypic assays demonstrated variable utility in identifying C. dubliniensis, but trends appear to exist. The use of chlamydoconidium production to identify C. dubliniensis isolates produced highly variable results and did not fully distinguish these isolates. However, of the isolates identified as C. dubliniensis, 16 of 23 (70%) had abundant chlamydoconidium production, indicative of C. dubliniensis, whereas only 1 of 28 (4%) of those identified as C. albicans had abundant chlamydoconidium production. In addition, most isolates tested were positive for fluorescence, which stands in contrast to data presented by Schoofs et al. (15) where all C. dubliniensis isolates failed to fluoresce. In the present study, 6 of 23 (29%) of the isolates showing poor Ca3 hybridization did not fluoresce, but of the isolates with Ca3 probe banding patterns indicative of C. albicans, only 3 of 28 (11%) did not fluoresce. Variability in the results obtained by using these phenotypic methods limit their utility for identifying these isolates.

API 20C was useful only when identification was confirmed as C. albicans. Fifteen of 23 (65%) of the isolates subsequently identified as C. dubliniensis were assigned “no ID” by API 20C, yet only 3 of 28 (11%) isolates identified as C. albicans by the Ca3 probe hybridization were not identified by API 20C. However, as reported by Salkin and colleagues previously (13), xylose assimilation was present in all 28 C. albicans isolates and in none of the 23 C. dubliniensis isolates. However, expense prohibits the routine use of API 20C in identifying germ tube-positive yeasts.

Differential temperature was useful in distinguishing C. albicans from C. dubliniensis. At 42 and 45°C, C. dubliniensis demonstrated negligible or no growth. All isolates identified as C. albicans grew well at 37 or 42°C. All twenty-two (100%) isolates with negligible growth at 42°C and one with growth at 42°C were confirmed as C. dubliniensis by using the Ca3 probe. However, in this study it should be noted that C. albicans did not grow as well at 42°C and that slight growth of C. dubliniensis can occur at 42°C, although growth was significantly reduced compared to that of C. albicans.

Pinjon and colleagues showed that all C. dubliniensis strains tested failed to grow at 45°C compared to growth of all but one strain of C. albicans at that temperature (7). However, in the present study, while none of the C. dubliniensis strains grew at 45°C, only 18 of 28 (64%) C. albicans isolates grew at that temperature, indicating that as a screening method, 45°C would falsely suggest the presence of C. dubliniensis in some cases.

Identification of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis was confirmed with fingerprinting of genomic DNA with the Ca3 probe. Twenty-eight of 29 isolates that grew well at 42°C had distinct hybridization patterns characteristic of C. albicans while 22 of 22 (100%) of the isolates that grew poorly at 42°C hybridized poorly and in a distinctive pattern, indicative of C. dubliniensis. Probes have recently been developed which are specific for C. dubliniensis, although use of these methods would be limited to a research setting (2, 3).

Although the pathogenicity of this yeast has not been established, C. dubliniensis was associated with clinical oropharyngeal infection in 16 of 22 (73%) cases and was present as the sole yeast isolate in 11 of 22 (50%) episodes. Risk factors and significance of this organism in oropharyngeal disease have also not been established. Isolation frequently occurred after several episodes of oropharyngeal infection but was found in the initial episode of oropharyngeal infection in five patients. Most strains remained susceptible to fluconazole although resistance or dose-dependent susceptibility occurred for three isolates. Increased susceptibility for the resistant strains was seen with itraconazole and the newer azoles, voriconazole and SCH 56592. Some isolates are resistant to fluconazole and may be more susceptible to other azole compounds.

In summary, the presence of atypical colonies on primary CHROMagar Candida cultures was used to identify isolates for further study. Differential temperature screening was extremely useful as a simple and inexpensive method for presumptively identifying C. dubliniensis from atypical C. albicans isolates for additional molecular studies (7). Twenty-two clinical isolates from 48 episodes of OPC in 63 patients were confirmed as C. dubliniensis by using a primary CHROMagar screening method followed by differential temperature growth and molecular studies to establish identity. Late-stage HIV-infected patients were found to have a C. dubliniensis prevalence rate of 17% in oropharyngeal samples by this approach. These isolates may show decreased susceptibility to fluconazole and may have increased susceptibility to newer azoles. Additional studies are needed to establish the epidemiology and significance of this organism in recurrent OPC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants 1 R01 DE11381 (to T.F.P.), 1 R29 AI42401 (to J.L.L.-R.), and M01-RR-01346 for the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center and by a grant from Pfizer Inc. New York, N.Y. R.A.C. was supported by a Summer Research Fellowship of the Medical Hispanic Center of Excellence at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Tex.

We thank Kevin Hazen and Julian Naglik for helpful comments and suggestions. CHROMagar Candida was provided by the CHROMagar Company, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman D C, Sullivan D J, Bennett D E, Moran G P, Barry H J, Shanley D B. Candidiasis: the emergence of a novel species, Candida dubliniensis. AIDS. 1997;11:557–567. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtzman C P, Robnett C J. Identification of clinically important ascomycetous yeasts based on nucleotide divergence in the 5′ end of the large-subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1216–1223. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1216-1223.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannarelli B M, Kurtzman C P. Rapid identification of Candida albicans and other human pathogenic yeasts by using short oligonucleotides in a PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1634–1641. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1634-1641.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran G P, Sullivan D J, Henman M C, McCreary C E, Harrington B J, Shanley D B, Coleman D C. Antifungal drug susceptibilities of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected subjects and generation of stable fluconazole-resistant derivatives in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:617–623. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard. Document M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson T F, Revankar S G, Kirkpatrick W R, Dib O P, Fothergill A W, Redding S W, Sutton D A, Rinaldi M G. Simple method for detecting fluconazole-resistant yeasts with chromogenic agar. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1794–1797. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1794-1797.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinjon E, Sullivan D, Salkin I, Shanley D, Coleman D. Simple, inexpensive, reliable method for differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;24:2093–2095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2093-2095.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redding S, Smith J, Farinacci G, Rinaldi M, Fothergill A, Rhine-Chalberg J, Pfaller M. Resistance of Candida albicans to fluconazole during treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in a patient with AIDS: documentation by in vitro susceptibility testing and DNA subtype analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:240–242. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revankar S G, Kirkpatrick W R, McAtee R K, Dib O P, Fothergill A W, Redding S W, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Detection and significance of fluconazole resistance in oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:821–827. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revankar S G, Dib O P, Kirkpatrick W R, McAtee R K, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G, Redding S W, Patterson T F. Clinical evaluation and microbiology of oropharyngeal infection due to fluconazole-resistant Candida in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;26:960–963. doi: 10.1086/513950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Pfaller M A. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rex J H, Pfaller M A, Galgiani J N, Bartlett M S, Espinel-Ingroff A, Ghannoum M A, et al. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:235–247. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salkin I F, Pruitt W R, Padhye A A, Sullivan D, Coleman D, Pincus D H. Distinctive carbohydrate assimilation profiles used to identify the first clinical isolates of Candida dubliniensis recovered in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1467. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1467-1467.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid J, Voss E, Soll D R. Computer-assisted methods for assessing strain relatedness in Candida albicans by fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive sequence Ca3. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1236–1243. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1236-1243.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoofs A, Odds F C, Colebunders R, Leven M, Goosens H. Use of specialized isolation media for recognition and identification of Candida dubliniensis isolates from HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:296–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01695634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.329-334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan D, Haynes K, Bille J, Boerlin P, Rodero L, Lloyd S, Henman M, Coleman D. Widespread geographic distribution of oral Candida dubliniensis strains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:960–964. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.960-964.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan D J, Henman M C, Moran G P, O’Neill L C, Bennett D E, Shanley D B, Coleman D C. Molecular genetic approaches to identification, epidemiology and taxonomy of non-albicans Candida species. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:399–408. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiballi R N, Zarins L T, He X, Kauffman C A. Torulopsis glabrata: azole susceptibilities by microdilution colorimetric and macrodilution broth assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2612–2615. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2612-2615.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]