Abstract

Background

Acupuncture, with many categories such as traditional acupuncture, electroacupuncture, laser acupuncture, and acupoint injection, has been shown to be relatively safe with few adverse effects. It is accessible and inexpensive, at least in China, and is likely to be widely used there for psychotic symptoms.

Objectives

To review the effects of acupuncture, alone or in combination treatments compared with placebo (or no treatment) or any other treatments for people with schizophrenia or related psychoses.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (February 2012), which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, EMBASE, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and clinical trials registries. We also inspected references of identified studies and contacted relevant authors for additional information.

Selection criteria

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials involving people with schizophrenia‐like illnesses, comparing acupuncture added to standard dose antipsychotics with standard dose antipsychotics alone, acupuncture added to low dose antipsychotics with standard dose antipsychotics, acupuncture with antipsychotics, acupuncture added to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) drug with TCM drug, acupuncture with TCM drug, electric acupuncture convulsive therapy with electroconvulsive therapy.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably extracted data from all included studies, discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and contacted authors of studies when necessary. We analysed binary outcomes using a standard estimation of risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, we calculated mean differences with 95% CI. For homogeneous data we used fixed‐effect model. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADE.

Main results

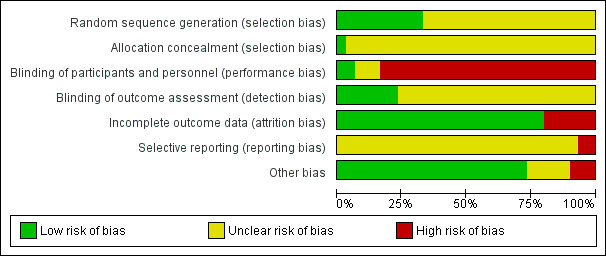

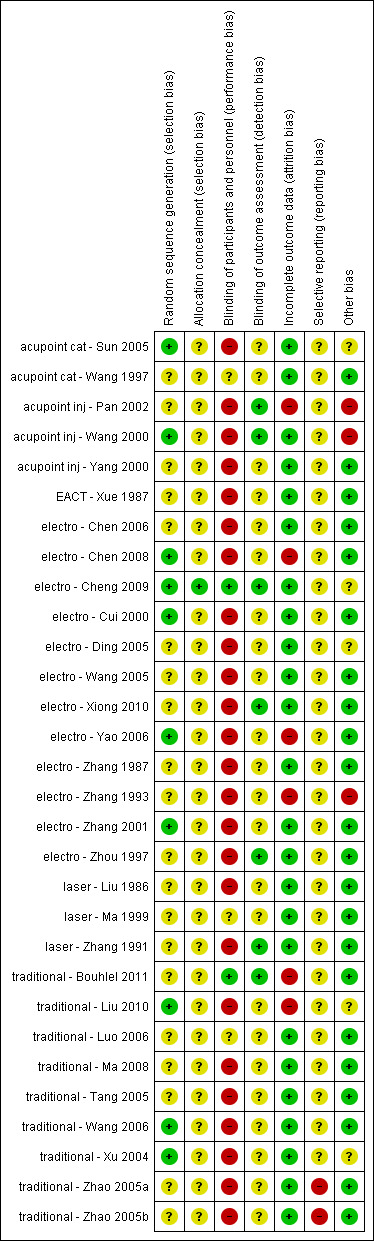

After an update search in 2012 the review now includes 30 studies testing different forms of acupuncture across six different comparisons. All studies were at moderate risk of bias.

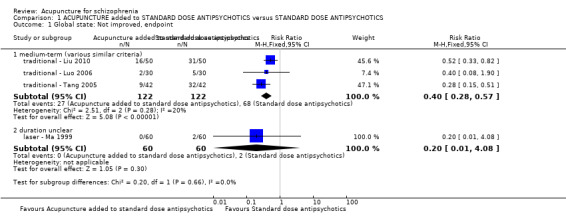

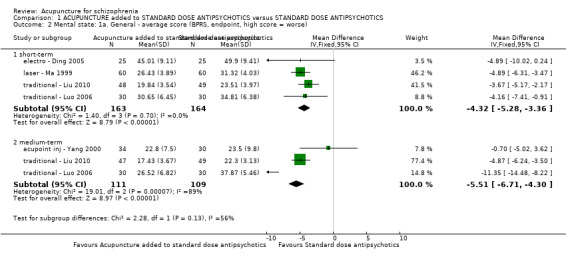

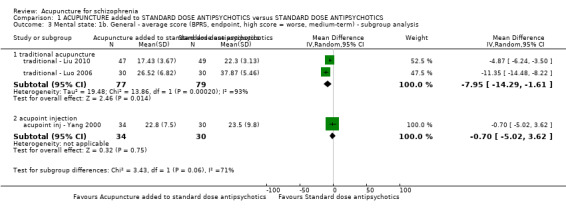

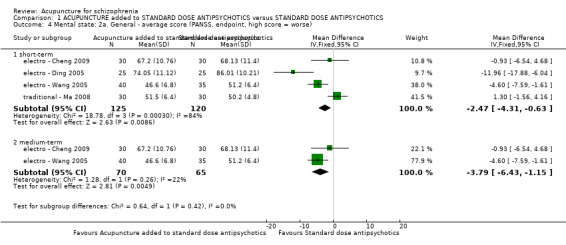

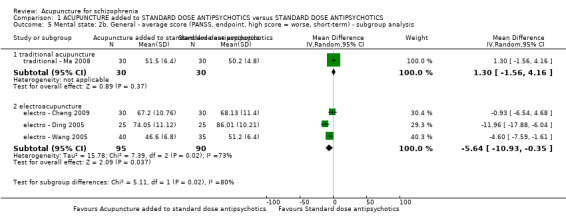

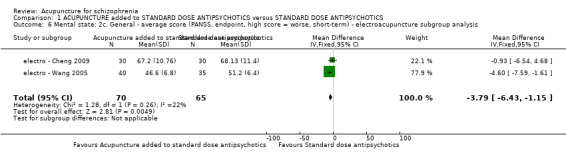

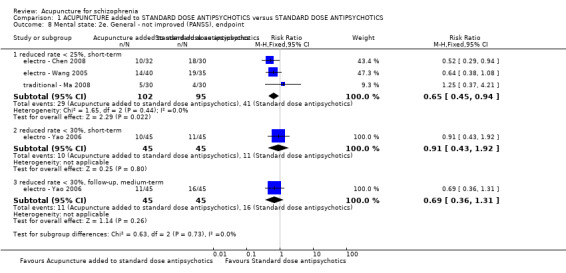

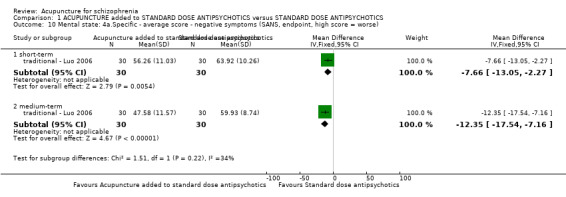

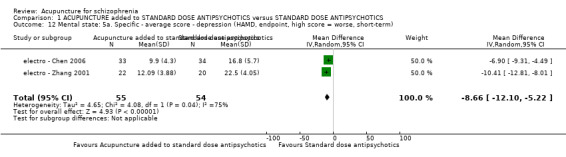

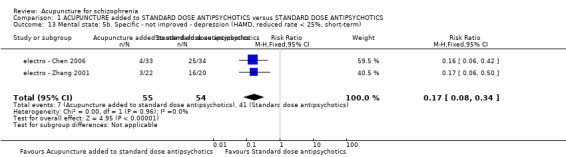

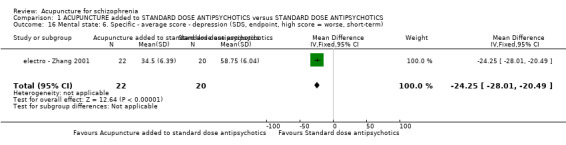

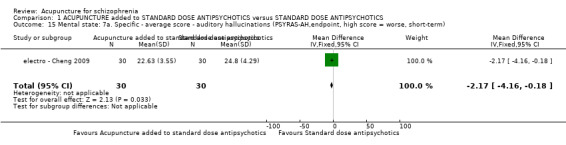

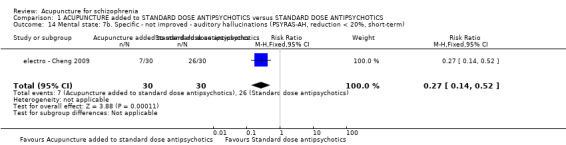

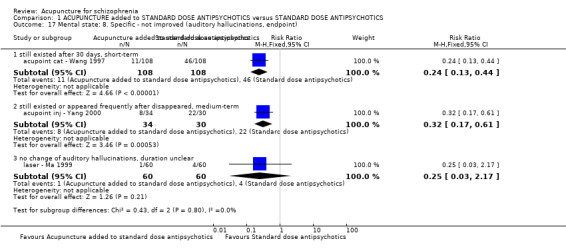

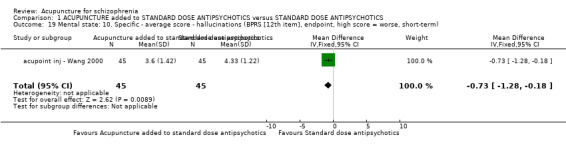

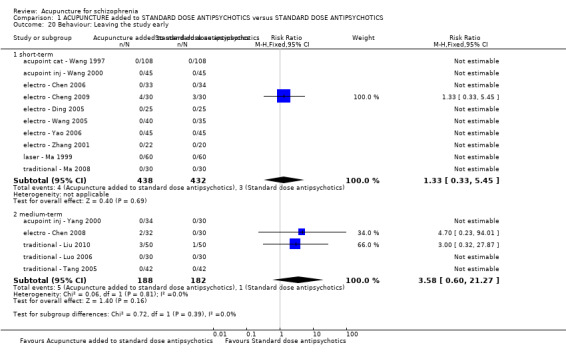

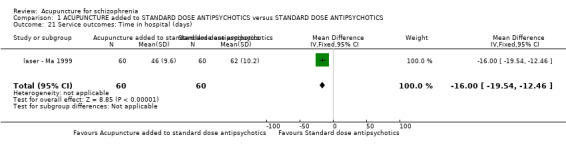

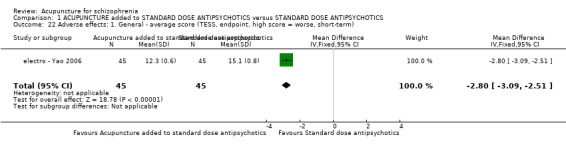

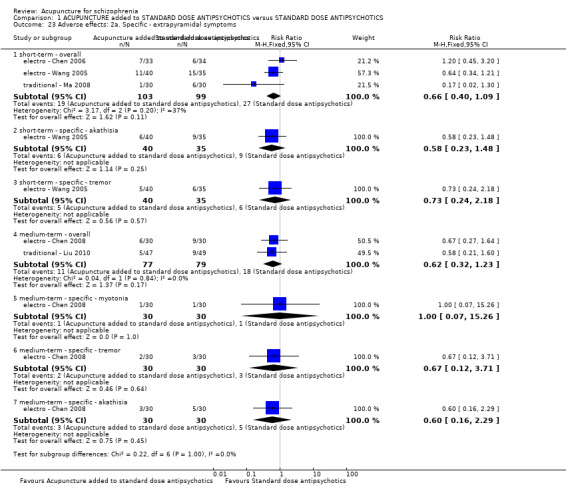

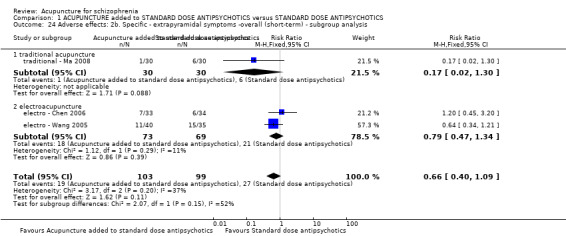

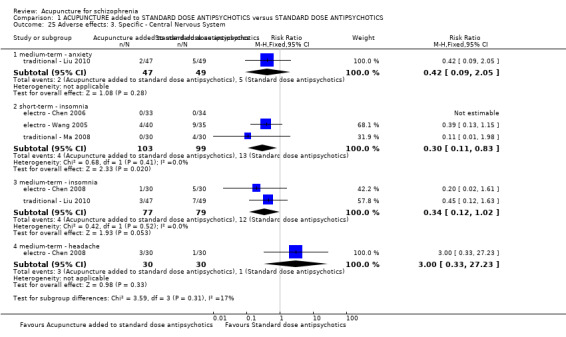

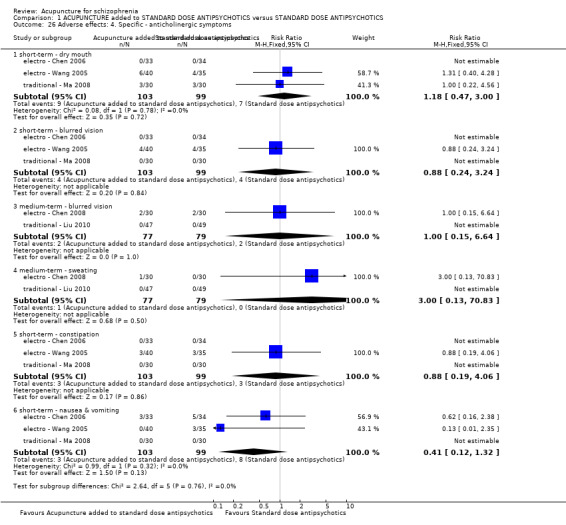

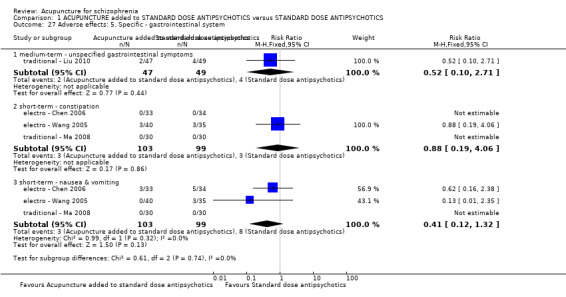

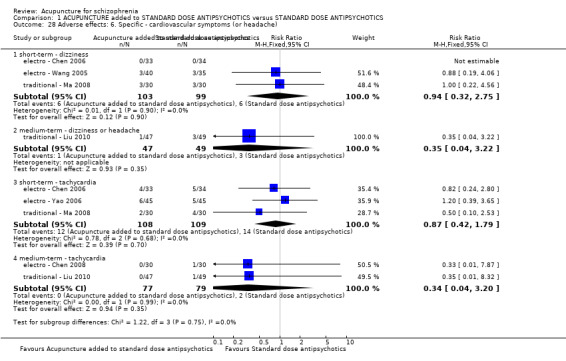

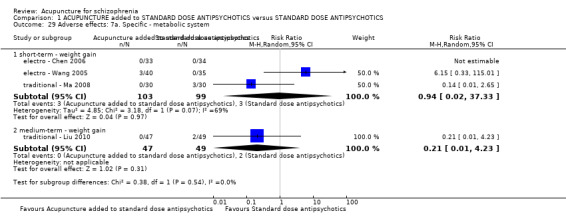

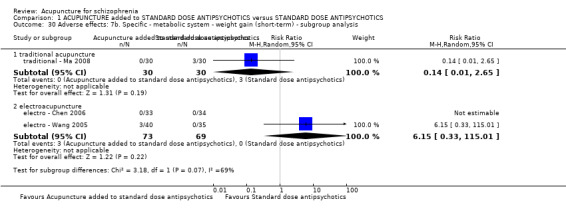

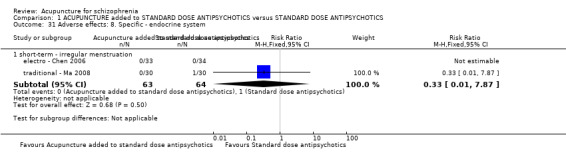

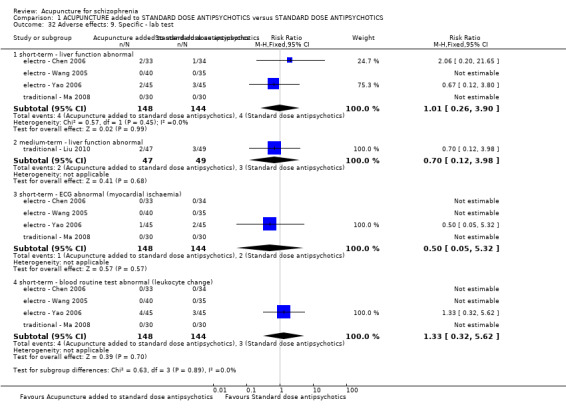

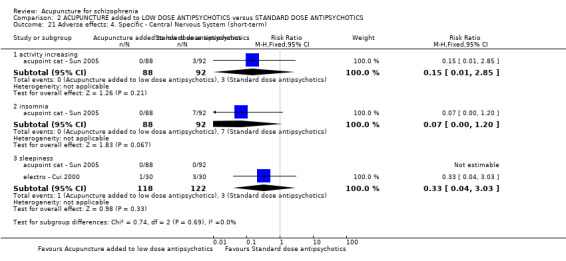

When acupuncture plus standard antipsychotic treatment was compared with standard antipsychotic treatment alone, people were at less risk of being 'not improved' (n = 244, 3 RCTs, medium‐term RR 0.40 CI 0.28 to 0.57, very low quality evidence). Mental state findings were mostly consistent with this finding as was time in hospital (n = 120, 1 RCT, days MD ‐16.00 CI ‐19.54 to ‐12.46, moderate quality evidence). If anything, adverse effects were less for the acupuncture group (e.g. central nervous system, insomnia, short‐term, n = 202, 3 RCTs, RR 0.30 CI 0.11 to 0.83, low quality evidence).

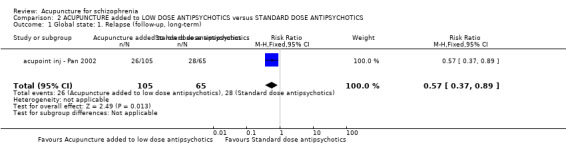

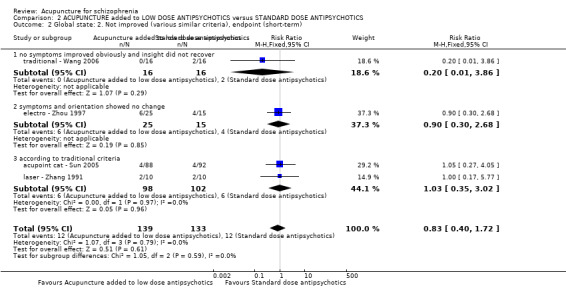

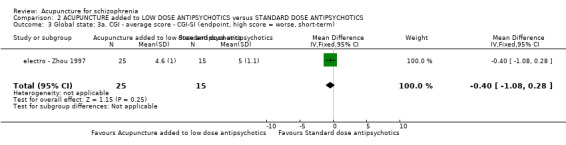

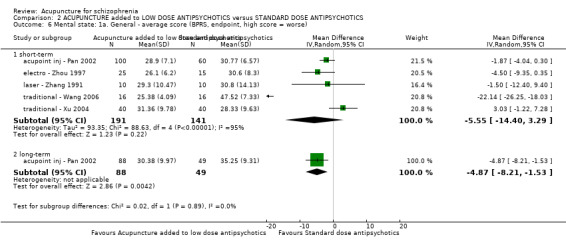

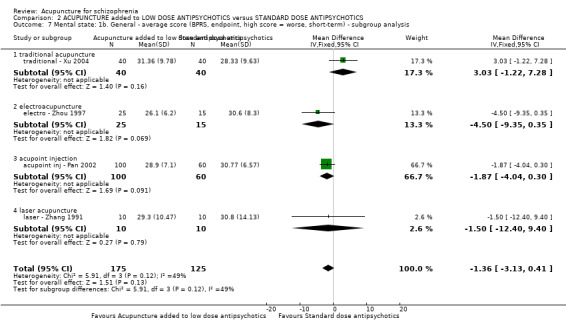

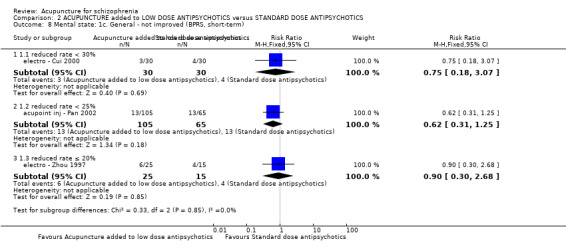

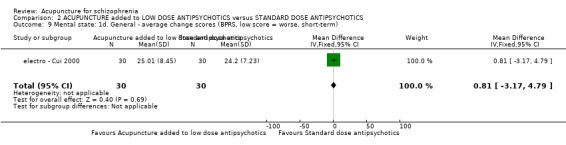

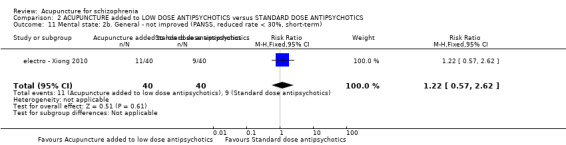

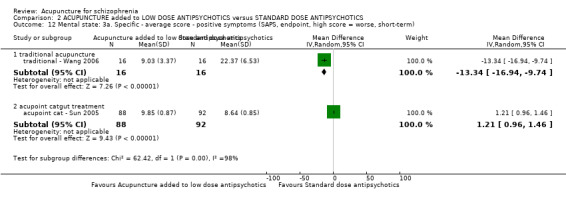

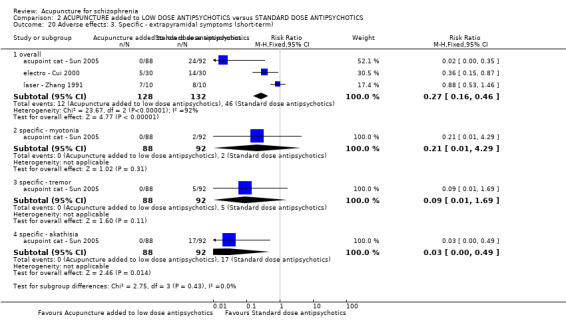

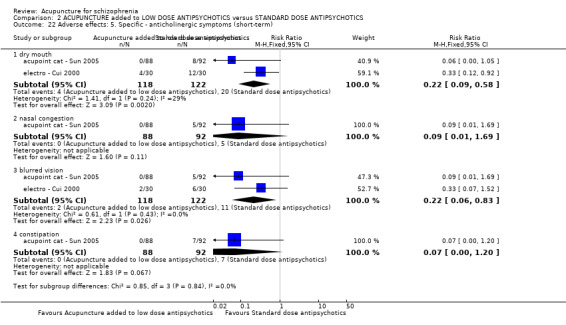

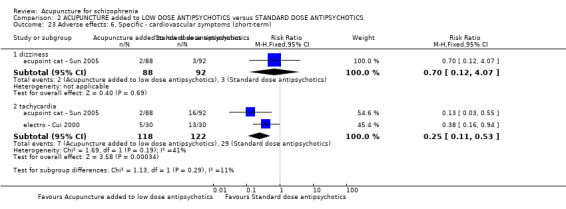

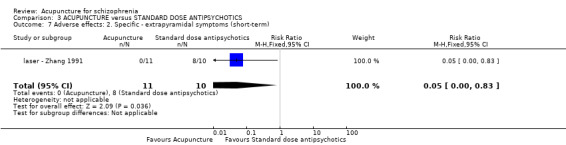

When acupuncture was added to low dose antipsychotics and this was compared with standard dose antipsychotic drugs, relapse was less in the experimental group (n = 170, 1 RCT, long‐term RR 0.57 CI 0.37 to 0.89, very low quality evidence) but there was no difference for the outcome of 'not improved'. Again, mental state findings were mostly consistent with the latter. Incidences of extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ akathisia, were less for those in the acupuncture added to low dose antipsychotics group (n = 180, 1 RCT, short‐term RR 0.03 CI 0.00 to 0.49, low quality evidence) ‐ as dry mouth, blurred vision and tachycardia.

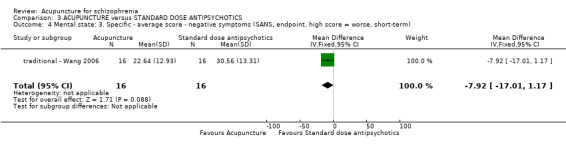

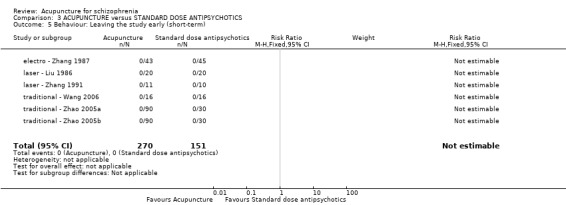

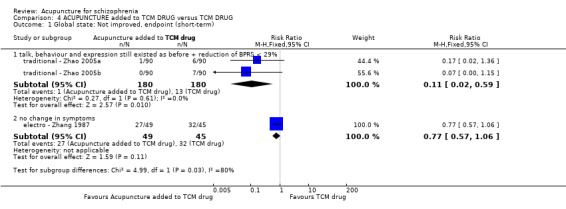

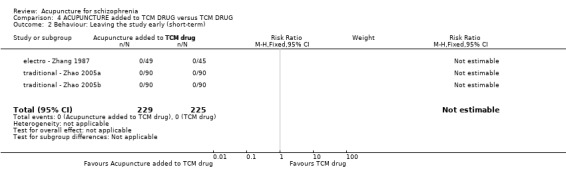

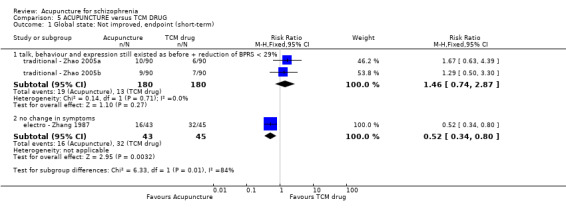

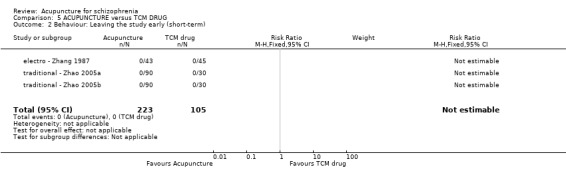

When acupuncture was compared with antipsychotic drugs of known efficacy in standard doses, there were equivocal data for outcomes such as 'not improved' using different global state criteria. Traditional acupuncture added to TCM drug had benefit over use of TCM drug alone (n = 360, 2 RCTs, RR no clinically important change 0.11 CI 0.02 to 0.59, low quality evidence), but when traditional acupuncture was compared with TCM drug directly there was no significant difference in the short‐term. However, we found that participants given electroacupuncture were significantly less likely to experience a worsening in global state (n = 88, 1 RCT, short‐term RR 0.52 CI 0.34 to 0.80, low quality evidence).

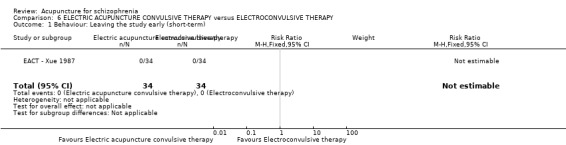

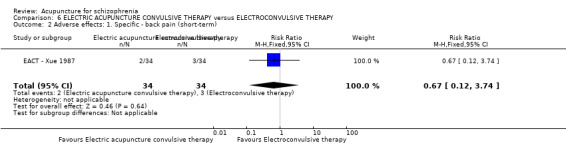

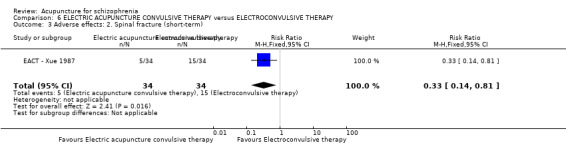

In the one study that compared electric acupuncture convulsive therapy with electroconvulsive therapy there were significantly different rates of spinal fracture between the groups (n = 68, 1 RCT, short‐term RR 0.33 CI 0.14 to 0.81, low quality evidence). Attrition in all studies was minimal. No studies reported death, engagement with services, satisfaction with treatment, quality of life, or economic outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Limited evidence suggests that acupuncture may have some antipsychotic effects as measured on global and mental state with few adverse effects. Better designed large studies are needed to fully and fairly test the effects of acupuncture for people with schizophrenia.

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for schizophrenia

Although acupuncture or Traditional Chinese Medicine has been practised for over 2000 years in China and the Far East, especially in Korea and Japan, it is a relatively new form of treament for physical and psychological conditions in the West. Acupuncture inserts needles into the skin to stimulate specific points of the body (acupoints). The aim is to achieve balance and harmony of the body.

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness and is usually treated using antipsychotic medication. However, although effective, antipsychotic medication can cause side‐effects (such as sleepiness, weight gain and even dribbling). Acupuncture has been shown to have very few negative effects on the individual and could be more socially acceptable and tolerable for people with mental health problems. Acupuncture may also be less expensive than drugs made by pharmaceutical companies, so reducing costs to individuals and health services.

This reviews looks at the effectiveness of various types of acupuncture as treatment for people with schizophrenia. An update search for studies was carried out in 2012 and found 30 studies that randomised participants who were receiving antipsychotic medication to receive additional acupuncture or standard care.

Although some of the studies did favour acupuncture when combined with antipsychotics, the information available was small scale and rated to be very low or low quality by the review authors, so not completely provable and valid. Depression was reduced when combining acupuncture with antipsychotic medication, but again this finding came from small‐scale research, so cannot be clearly shown to be true. The review concludes that people with mental health problems, policy makers and health professionals need much better evidence in order to establish if there are any potential benefits to acupuncture.

This means that the question of whether acupuncture is of benefit to people, and whether it is of greater benefit than antipsychotic medication, remains unanswered. There is not enough information to establish that acupuncture is of benefit or harm to people with mental health problems.

Benjamin Gray, Service User and Service User Expert, Rethink Mental Illness.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. ACUPUNCTURE added to STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia.

| ACUPUNCTURE added to STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ACUPUNCTURE added to STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ACUPUNCTURE added to STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS | |||||

| Global state: Not improved, endpoint ‐ medium‐term (various similar criteria) | 557 per 1000 | 223 per 1000 (156 to 318) | RR 0.4 (0.28 to 0.57) | 244 (3 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Relapse was not reported but 'no clinically important change in global state' was reported and another outcome without clear duration indicated no difference between two comparison groups. |

| Mental state: PANSS (not improved, reduced rated < 25%, short‐term) | 432 per 1000 | 281 per 1000 (194 to 406) | RR 0.65 (0.45 to 0.94) | 197 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Data from PANSS were equivocal because of different criteria. Other mental state findings were mostly consistent with this finding. |

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | 7 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (2 to 38) | RR 1.33 (0.33 to 5.45) | 870 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | Similar outcomes at medium‐term. |

| Service outcomes: Time in hospital (days) | The mean service outcomes: time in hospital (days) in the intervention groups was 16 lower (19.54 to 12.46 lower) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | 0nly one study reported service outcomes ‐ time in hospital. | ||

| Adverse effects: Central Nervous System ‐ insomnia (short‐term) | 131 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (14 to 109) | RR 0.30 (0.11 to 0.83) | 202 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | Only insomnia rate indicated difference between two compared groups. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel and incomplete outcome data. 2 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events. 3 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strong suspected' ‐ One author worked for drug industry.

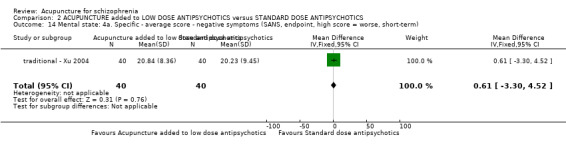

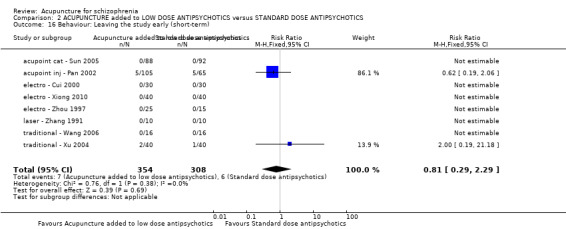

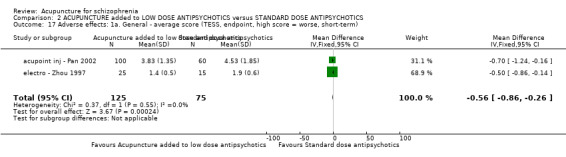

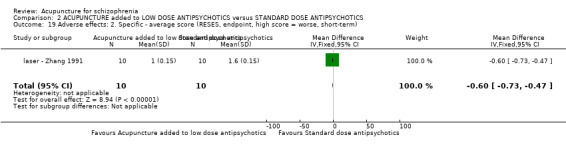

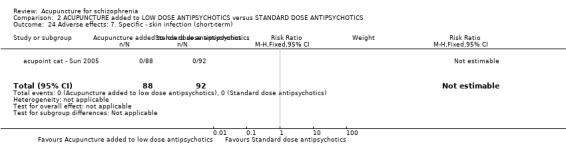

Summary of findings 2. ACUPUNCTURE added to LOW DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia.

| ACUPUNCTURE added to LOW DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ACUPUNCTURE added to LOW DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ACUPUNCTURE added to LOW DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS | |||||

| Global state: Relapse (follow‐up, long‐term) | 431 per 1000 | 246 per 1000 (159 to 383) | RR 0.57 (0.37 to 0.89) | 170 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Only one study reported this outcome. Other global state findings reported no difference between the two comparison groups. |

| Mental state: BPRS (not improved, reduced rate < 30%, short‐term) | 133 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (24 to 409) | RR 0.75 (0.18 to 3.07) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | Though measured with different criteria of 'no clinically important change in general mental state', there was no difference between the two comparison groups at short‐term and mostly similar results from other mental state findings. |

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | 19 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 45) | RR 0.81 (0.29 to 2.29) | 662 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms ‐ specific ‐ akathisia (short‐term) | 185 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (0 to 91) | RR 0.03 (0 to 0.49) | 180 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | Similar to the akathisia data, acupuncture added to low dose antipsychotics reduced participants experiencing dry mouth, blurred vision, tachycardia at short‐term. Only one study focused on acupoint catgut treatment relative adverse effects but did not find skin infection in either groups. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel and incomplete outcome data. 2 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events. 3 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ There was some difference between two references of the same study. 4 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 5 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events and wide confidence intervals.

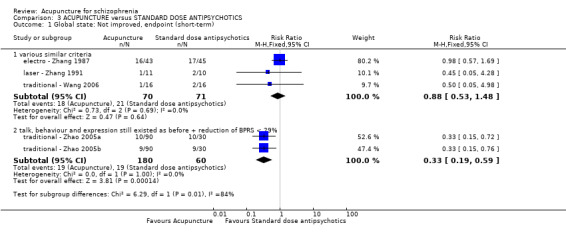

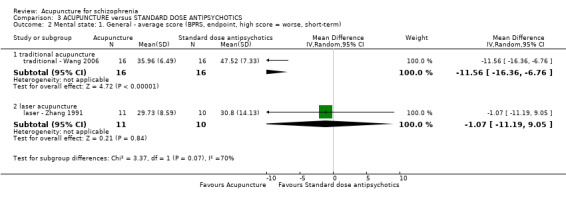

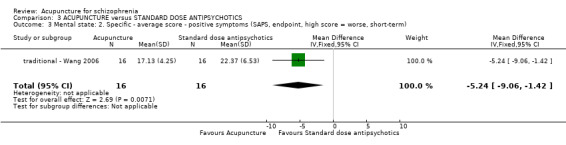

Summary of findings 3. ACUPUNCTURE versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia.

| ACUPUNCTURE versus STANDARD DOSE ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ACUPUNCTURE versus ANTIPSYCHOTICS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ACUPUNCTURE versus ANTIPSYCHOTICS | |||||

| Global state: Not improved (talk, behaviour and expression still existed as before; the reduction of BPRS < 29%), endpoint (short‐term) | 317 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (60 to 187) | RR 0.33 (0.19 to 0.59) | 240 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Relapse was not reported but 'no clinically important change in global state' was reported and another three outcomes with different but similar criteria indicated no difference between the two comparison groups in the short‐term. |

| Mental state: BPRS, endpoint (high score = worse, short‐term) ‐ traditional acupuncture | The mean mental state: BPRS, endpoint (high score = worse, short‐term) ‐ traditional acupuncture in the intervention groups was 11.56 lower (16.36 to 6.76 lower) | 32 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | The outcome of 'no clinically important change in general mental state' was not reported but average endpoint BPRS data were reported as was the SAPS score. There was no difference between the two comparison groups in the short‐term using either score. | ||

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 421 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | No participants left each compared group early. |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

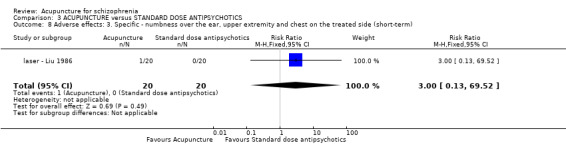

| Adverse effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms (short‐term) | 800 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (0 to 664) | RR 0.05 (0 to 0.83) | 21 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | One study reported laser acupuncture relative adverse effects ‐ numbness over ear, upper extremity and chest on the treated side, but no difference between the two comparison groups. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 2 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events and wide confidence intervals. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events.

Summary of findings 4. ACUPUNCTURE added to TCM DRUG versus TCM DRUG for schizophrenia.

| ACUPUNCTURE plus TCM DRUG versus TCM DRUG for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ACUPUNCTURE added to TCM DRUG versus TCM DRUG | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ACUPUNCTURE added to TCM DRUG versus TCM DRUG | |||||

| Global state: Not improved (talk, behaviour and expression still existed as before, the reduction of BPRS < 29%), endpoint (short‐term) | 72 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (1 to 43) | RR 0.11 (0.02 to 0.59) | 360 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Relapse was not reported but 'no clinically important change in global state' was reported and the other outcome with different criteria of 'no clinically important change in global state' indicated no difference between the two comparison groups in the short‐term. |

| Mental state: No clinically important change in mental state | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 454 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | No participants left either group early. |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effects | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Three studies reported this outcome, however, two studies only reported one group's data and the other one study did not report the data. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 2 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few events.

Summary of findings 5. ACUPUNCTURE versus TCM DRUG for schizophrenia.

| ACUPUNCTURE versus TCM DRUG for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ACUPUNCTURE versus TCM DRUG | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ACUPUNCTURE versus TCM DRUG | |||||

| Global state: Not improved, endpoint (short‐term) ‐ Not improved (no change in symptoms) ‐ Electroacupuncture | 711 per 1000 | 370 per 1000 (242 to 569) | RR 0.52 (0.34 to 0.80) | 88 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Relapse was not reported but 'no clinically important change in global state' was reported and other outcomes with different criteria of 'no clinically important change in global state' indicated no difference between the two comparison groups in the short‐term. |

| Mental state: No clinically important change in general mental state | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 328 (3 studies) | See comment | No participants left either group early. |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Adverse effects: Clinically important general adverse effects | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Three studies reported this outcome, however, two studies only reported one group's data and the other one study did not report the data. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 2 Impression: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and/or few evens.

Summary of findings 6. ELECTRIC ACUPUNCTURE CONVULSIVE THERAPY versus ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY for schizophrenia.

| ELECTRIC ACUPUNCTURE CONVULSIVE THERAPY versus ELECTRIC CONVULSIVE THERAPY for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Intervention: ELECTRIC ACUPUNCTURE CONVULSIVE THERAPY versus ELECTRIC CONVULSIVE THERAPY | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ELECTRIC ACUPUNCTURE CONVULSIVE THERAPY versus ELECTRIC CONVULSIVE THERAPY | |||||

| Global state: Relapse | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Mental state: No clinically important change in general mental state | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Behaviour: Leaving the study early (short‐term) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 68 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | No participants in either group left early. |

| Service outcomes: Hospitalisation | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Adverse effects: Spinal fracture (short‐term) | 441 per 1000 | 146 per 1000 (62 to 357) | RR 0.33 (0.14 to 0.81) | 68 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Data from a single study where there was no difference in back pain between the two groups. |

| Quality of life: No clinically important change in quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| Economic outcomes: Cost of care | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias; rated 'serious' ‐ Unblinding of participants and personnel. 2 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ Few participants and few events.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia affects 1% of people and therefore, one fifth of people with schizophrenia are of Chinese origin. In Chinese health care, theories for the aetiology, pathology and treatment of schizophrenia are different to those of Western medicine. Conventional medicine diagnoses schizophrenia primarily by operationalised criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM‐IV) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10). Chinese medicine uses different methodology to diagnose mental health disorders such as schizophrenia by pattern differentiation. The four diagnostic methods (inspection, listening/smelling, inquiry and palpation) are the way by which patient information is obtained (Xu 1991). This information is then analysed using one or several diagnostic models (Zang Fu theory, Eight Principles [yin/yang, interior/exterior, excess/deficiency, hot/cold], Four Division Pattern [Wei Qi Ying Xue ], Six Division Pattern, Five Elements Pattern [wood, fire, earth, metal, and water], Pattern of Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids, Three Burners Pattern) to arrive at a diagnosis. Thus, two people diagnosed with DSM‐IV schizophrenia could nevertheless, from a Chinese medicine perspective, have different sub‐types or patterns and therefore require different treatment. The Psychosis Professional Committee of Chinese Integrative Medicine Association drafted the Standard of Integrative Medicine Syndrome Type of Schizophrenia. There are six main patterns which fall within the disease category of Dian Kuang/withdrawal mania which can also encompass schizophrenia. The six types are: 1. Internal disturbance of pyrophlegm; 2. Internal retention of phlegm and dampness; 3. Qi stagnation and blood stasis; 4. Yin deficiency and fire excess; 5. Yang deficiency; 6.Other miscellaneous types (The Psychosis Professional Committee 1988; Guo 2010; Zhang 1996).

Description of the intervention

The illness often causes distortions of perception, thinking, behaving and even movement and, although antipsychotic drugs have been the mainstay of treatment of schizophrenia since the early 1950s, these treatments still leave many with residual symptoms and disabling adverse effects. Acupuncture (Figure 1) has been shown to have few adverse effects (Ernst 2001; MacPherson 2001) and may be more socially acceptable, tolerable and inexpensive than the more conventional drugs available from the pharmaceutical industry. Chinese medicine, which includes acupuncture and is also referred to as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), has been used to treat 'schizophrenia‐like illnesses' (i.e. Dian Kuang/withdrawal mania) for over 2000 years (Ming 2001). Acupuncture is practiced as an accepted healthcare model in China, Korea and Japan, although the methods used in each country are distinct (Kaptchuk 2002). There are many categories of acupuncture such as traditional acupuncture, electroacupuncture, laser acupuncture, and acupoint injection.

1.

Acupuncture

How the intervention might work

Acupuncture involves the stimulation of specific points (acupoints). The internal diseases are treated using external applications by dredging meridians, regulating Yin and Yang, reinforcing the healthy Qi and eliminating the pathogenic factors. Though acupuncture has a long history, any mechanism for treating schizophrenia is still unclear (Shi 2010; Xu 2010). Acupuncture may affect the central nervous functions of the cerebral cortex through recuperating the Qi, blood, dredging meridians and then adjusting the nervous system's functions and endocrine level (Wang 2007). There is, however, not enough modern neural physiological and biochemical research, imaging or animal studies to support this (Xu 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

Acupuncture has been used to treat schizophrenia for many years and now it is considered as one of the most popular types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in Western health care. We wish to update past work, undertake a review that is systematic and quantify the effects of this inexpensive treatment.

Objectives

To review the effects of acupuncture for people with schizophrenia and related psychoses, evaluating acupuncture alone or in combination regimens compared with placebo (or no treatment), or any other treatments.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. We planned that if a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but it was implied that the study was randomised, these trials would have been included in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see 'Types of outcome measures') when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then they would have been included in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, only clearly randomised trials would have been utilised and the results of the sensitivity analysis described in the text. Quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded.

Types of participants

We included patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform psychosis and schizophrenia‐like illnesses, any age, diagnosed by any criteria.

Types of interventions

1. All categories of acupuncture

Administered solely or in conjunction with any other treatments, versus:

2. Placebo (sham acupuncture) or no treatment

3. Any other treatments

We do recognise that there are other possible combinations of treatments that could be included in this review but this (2012) update focused on only the above comparisons.

For previous type of interventions please see Appendix 1.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were divided into short‐term (less than three months), medium‐term (three to 12 months) and long‐term (more than one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Relapse

2. Mental state

2.2 No clinically important change in general mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

3. Service outcomes

3.1 Hospitalisation

4. Adverse effects

4.1 Clinically important general adverse effects

Secondary outcomes

1. Death ‐ suicide or natural causes

2. Global state

2.1 No clinically important change in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.2 Average endpoint global state score 2.3 Average change in global state scores

3. Mental state

3.1 No change in general mental state 3.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 3.3 Average change in general mental state scores 3.4 No clinically important change in specific symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.5 No change in specific symptoms 3.6 Average endpoint specific symptom score 3.7 Average change in specific symptom scores

4. Behaviour

4.1 Leaving the study early 4.2 No clinically important change in general behaviour ‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 No change in general behaviour 4.4 Average endpoint general behaviour score 4.5 Average change in general behaviour scores 4.6 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 4.7 No change in specific aspects of behaviour 4.8 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 4.9 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

5. Service outcomes

5.1 Time to hospitalisation

6. Adverse effects

6.1 Any general adverse effects 6.2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 6.3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 6.4 No clinically important change in specific adverse effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 6.5 No change in specific adverse effects 6.6 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 6.7 Average change in specific adverse effects

7. Engagement with services

7.1 No clinically important engagement ‐ as defined by each of the studies 7.2 No engagement 7.3 Average endpoint engagement score 7.4 Average change in engagement scores

8. Satisfaction with treatment

8.1 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 8.2 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 8.3 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores

9. Quality of life

9.1 No clinically important change in quality of life ‐ as defined by each of the studies 9.2 No change in quality of life 9.3 Average endpoint quality of life score 9.4 Average change in quality of life scores

10. Economic outcomes

10.1 Costs of care

11. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used the GRADE profiler to import data from Review Manager (RevMan) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

1. Global state: relapse. 2. Mental state: no clinically important change in general mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 3. Behaviour: leaving the study early. 4. Service outcomes: hospitalisation. 5. Adverse effects: clinically important general adverse effects. 6. Quality of life: no clinically important change in quality of life ‐ as defined by each of the studies. 7. Economic outcomes: costs of care.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Registry of Trials (February 2012) using the following search strategies:

(*acup* or *moxibustion*) in Title Field of REFERENCE or (*acupuncture* or *moxibustion*) in Intervention Field of STUDY

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Registry of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

For previous searches, see Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all identified studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Methods used in data collection and analysis for this 2012 update are below; for previous methods, please see Appendix 3.

Selection of studies

For this 2012 update, review author XS independently inspected citations from the new electronic search and identified relevant abstracts. XS also inspected full articles of the abstracts meeting inclusion criteria. JX carried out the reliability check of all citations from the new electronic search. Where disputes arose, we resolved disagreements by discussion or, if doubt remained, by acquiring the full article for more detailed scrutiny. If doubt still remained, we added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment pending acquisition of further information and we contacted the authors of studies. For details of previous author contributions in study selection see Acknowledgements.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For this 2012 update, XS extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, JX independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. We discussed disagreements, documented our decisions and, if necessary, contracted authors of studies for clarification. With any remaining problems, CEA helped clarify issues, although he could not translate the Mandarin text. When uncertainty persisted, we allocated the trial to Studies awaiting classification. Data presented only in graphs and figures were extracted whenever possible, but included only if two review authors independently extracted the same results. In order to obtain missing information or for clarification, whenever necessary we contacted authors through an open‐ended request . If studies were multi‐centre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly; we have noted whether or not this is the case in Description of studies.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences throughout (Higgins 2011, Chapter 9.4.5.2).

Previous version of this review did not combine endpoint and change data in the analysis (see Appendix 3).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion: a) standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996); c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), (Kay 1986)), which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above will be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large (>200) and we will enter these into the syntheses. We presented skewed endpoint data from studies of less than 200 participants as 'Other data' in the Data & analyses rather than enter such data in analyses. When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We planned to present and enter change data into analyses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for acupuncture. If we had to enter data so the area to the left of the line indicated a favourable outcome for the control treatment, this was noted in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this 2012 update, XS worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This new set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. JX assessed risk of bias from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total.

Any disagreements between raters were resolved through discussion with CEA. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. All disagreements in quality assessment were recorded and reported. If disputes arose as to which quality category a trial was to be rated, again, we resolved these through discussion.

We have noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

The previous version of this review used a different, less well‐developed, means of categorising risk of bias (see Appendix 3).

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The Number Needed to Treat/Harm (NNT/H) statistic with its confidence intervals is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We would prefer not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we would have calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If cluster trials where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies had been included, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We would have contacted the first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC had not been reported, it would have been assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase, the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a washout phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, if we had identified any cross‐over trials, we would only have used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we would have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary we would simply add these and combine within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we would have combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Handbook (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, if for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses, (except for the outcome 'leaving the study early'). If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we would mark such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

The previous version of this review excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow‐up (see Appendix 3).

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of those who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ was used for those who did not. If the above assumptions had been used for the primary outcomes we would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

When standard deviations were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. When not available, where there are missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals are available for group means, and either a P value or T value available for differences in mean, we could calculate them according to the rules described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, standard deviations (SDs) are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Handbook (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, T or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae do not apply, we can calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. If possible, we planned to examine the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, if LOCF data had been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we would have reproduced these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

The previous version of this review used a different, less‐well developed approach to deal with heterogeneity (see Appendix 3).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Handbook (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots are possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

The previous version of this review used a different, less‐well developed approach to assess the reporting biases (see Appendix 3).

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose the fixed‐effect model for all analyses. we only used random‐effects model when heterogeneity was present.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of acupuncture for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, if possible, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we have reported this. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present data. If not, then we did not pool data and discussed issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off, but we use prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We do not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

Had we found trials which were described in some way so as to imply randomisation, we would have included these in a sensitivity analysis. For the primary outcomes we would have included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we would have entered all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them, but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), if possible, we compared the findings of outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them, but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available): allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

If we had found cluster randomised trials we would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster randomised trials.

If we had undertaken sensitivity analysis and noted substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we would not have pooled data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but would have presented them separately.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of studies please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Previous version of description of studies please see Appendix 4.

Results of the search

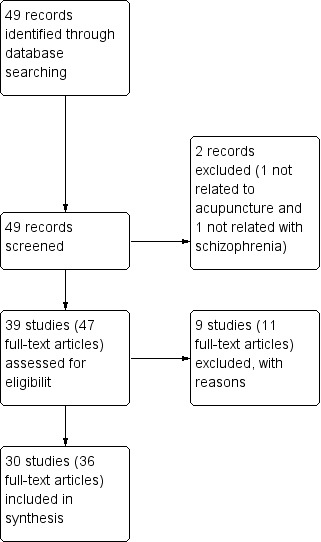

The update searches in 2012 yielded references to 49 reports including all the reports in the previous version (Figure 2). We selected 39 studies with 47 reports for further inspection of full papers excluding 2 records for one not relating to acupuncture and one not relating with schizophrenia after initial appraisal. We were able to include 30 studies with 36 reports.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included thirty studies.

1. Allocation

All included studies were randomised controlled trials. Only 10 of the included studies described the randomisation method. Three studies used a random sampling method (acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005; electro ‐ Chen 2008; electro ‐ Zhang 2001); three were randomised by using a random allocation table (traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004); two drew lots (acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; electro ‐ Yao 2006); one study used the SAS program ‐ this was the only trial that described allocation concealment by using opaque sealed envelopes (electro ‐ Cheng 2009) and one used the coin‐tossing method (electro ‐ Cui 2000). Five studies were assessor‐blinded (acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002; acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; electro ‐ Xiong 2010; electro ‐ Zhou 1997; laser ‐ Zhang 1991); two were patient‐ and assessor‐blinded (electro ‐ Cheng 2009; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011); and we could not ascertain how blinding was achieved in traditional ‐ Liu 2010, although it was reported as single blind.

2. Study duration

Study duration varied from two weeks (acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000) to six months (acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000). The majority of studies were short‐term. Five of all included studies were medium‐term (acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; electro ‐ Chen 2008; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Tang 2005) and the duration of laser ‐ Ma 1999 was unclear. acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002 had a two‐year follow‐up and electro ‐ Yao 2006 a six‐month follow‐up.

3. Setting

Twenty‐two studies were hospital‐based with inpatients. Two studies, electro ‐ Chen 2006 and traditional ‐ Ma 2008, were undertaken with both inpatients and outpatients. Two studies were undertaken with outpatients (traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b). The settings of the four remaining studies were not mentioned (acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; laser ‐ Liu 1986; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; EACT ‐ Xue 1987).

4. Country

All included studies were undertaken in China except one traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011, which took place in Tunisia.

5. Participants

It was reported in all studies that the participants suffered from schizophrenia. Seventeen adopted the standards of Chinese Classification of Mental Disorder such as second edition (CCMD‐2, acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; laser ‐ Ma 1999), second edition revision (CCMD‐2‐R, acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002; acupoint cat ‐ Wang 1997; acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; electro ‐ Cui 2000; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; traditional ‐ Xu 2004) or third edition (CCMD‐3, acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005; electro ‐ Chen 2006; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Xiong 2010; electro ‐ Yao 2006; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Tang 2005). Two studies diagnosed schizophrenia according to DSM IV (electro ‐ Cheng 2009; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011). Two studies diagnosed schizophrenia with both CCMD‐3 and Andreasen's diagnosis standards (electro ‐ Chen 2008; electro ‐ Wang 2005); two with both standards of CCMD‐2‐R and DSM III (laser ‐ Zhang 1991) or CCMD‐2‐R and ICD‐10 (electro ‐ Zhang 2001); three with both standards of TCM and CCMD‐2‐R (traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b) or TCM and CCMD‐3 (traditional ‐ Ma 2008). Only one study (electro ‐ Zhou 1997) adopted three standards ‐ DSM III, CCMD and TCM. The other three studies did not mention the diagnostic standard (EACT ‐ Xue 1987; electro ‐ Zhang 1987; laser ‐ Liu 1986).

The age of participants of 15 studies ranged from 15 to 67 years. Three studies did not definitely describe the age range (traditional ‐ Tang 2005; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b). The other 12 studies reported mean age. The majority of studies included both women and men except electro ‐ Ding 2005 and traditional ‐ Xu 2004 (only men). acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002 and electro ‐ Zhang 1993 did not describe gender. All studies except traditional ‐ Tang 2005 reported the history of illness.

6. Study size

The number of participants ranged from 31 to 300; acupoint cat ‐ Wang 1997, traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a and traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b were over 200 participants. The size of electro ‐ Zhang 1993 was unclear.

7. Interventions

We found six categories of acupuncture were used whether alone or in combination regimens: traditional acupuncture, electroacupuncture, acupoint injection, laser acupuncture, acupoint catgut treatment and electric acupuncture convulsive therapy. Traditional acupuncture included acupuncture manipulation and moxibustion. Acupuncture manipulation refers to an operation method to prevent disease by using different needles or non‐needle way to stimulate the specific points (acupoints) with certain practices or methods. Moxibustion not only refers to burning, smoking and ironing body surface mainly using moxa but also refers to any external treatment of non‐fire source (Shi 2007). Electroacupuncture refers to a combination method of needles and electrical stimulation to prevent disease that connects needles with trace current which are close to the human bio‐electricity after inserting needles into acupoints and getting the feeling of 'DeQi' (Shi 2007). Acupoint injection, guiding by the basic theory of Chinese medicine, is a treatment method with synergistic effects of acupuncture manipulation and drugs, which is to inject drugs into relative acupoint or special point (Tang 2010). Laser acupuncture, guiding by the basic theory of Chinese medicine, is a treatment method of preventing disease, treating disease, and health care to stimulate acupoints effectively using low‐intensity laser beam to irradiate acupoints directly, focus on acupoints or with beam expander (Fan 2010). Acupoint catgut treatment, guiding by the basic theory of Chinese medicine, is an external treatment method of treating diseases with catgut's stimulation effects on acupoints by using different types of catgut to embed acupoints selectively (Meng 2012). Electric acupuncture convulsive therapy, deriving from acupuncture, is a treatment method for mental disorders by using subconvulsive stimulating currents and with the electrodes in acupoints (Baihui and Renzhong) (Xue 1985).

7.1 Acupuncture added to standard dose antipsychotics

7.1.1 Acupuncture

The categories of acupuncture were traditional acupuncture (traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Ma 2008; traditional ‐ Tang 2005); electroacupuncture (electro ‐ Chen 2006; electro ‐ Chen 2008; electro ‐ Cheng 2009; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Wang 2005; electro ‐ Yao 2006; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; electro ‐ Zhang 2001); acupoint injection (acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000); laser acupuncture (laser ‐ Ma 1999); and acupoint catgut treatment (acupoint cat ‐ Wang 1997). None of the above acupuncture interventions were the same.

7.1.2 Antipsychotics

Five studies used risperidone and the dose of four of these studies (electro ‐ Wang 2005; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Ma 2008) ranged from 2 to 6 mg/d. electro ‐ Cheng 2009 used the average dosage of 5.15 ± 0.46 mg/d. One study, electro ‐ Chen 2008, used aripiprazole (average dosage 18.4 ± 6.2 mg/d); one, electro ‐ Yao 2006, used clozapine (total dosage 200 to 300 mg/d); and one, laser ‐ Ma 1999, chlorpromazine (average dosage 395 ± 55 mg/d). The other three studies did not describe more details of antipsychotics (acupoint cat ‐ Wang 1997; electro ‐ Zhang 2001; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011). The remaining six studies reported that people remained on previous antipsychotics treatment (acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; electro ‐ Chen 2006; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; traditional ‐ Tang 2005).

7.2 Acupuncture added to low dose antipsychotics

7.2.1 Acupuncture

The categories of acupuncture were traditional acupuncture (traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004), electroacupuncture (electro ‐ Cui 2000; electro ‐ Xiong 2010; electro ‐ Zhou 1997), acupoint injection (acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002), laser acupuncture (laser ‐ Zhang 1991) and acupoint catgut treatment (acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005). None of them were identical.

7.2.2 Low dose antipsychotics

Five studies (acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002; electro ‐ Cui 2000; laser ‐ Zhang 1991; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004) used chlorpromazine less than 300 mg/d. One study, electro ‐ Xiong 2010, reported the use of clozapine 100 to 150 mg/d, and another study, acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005, used risperidone 1 to 2 mg/d. Finally, electro ‐ Zhou 1997 described the dosage of the antipsychotics was a reduction of ˜60% of their previous daily levels.

7.3 Acupuncture added to TCM drug

7.3.1 Acupuncture

Two studies used traditional acupuncture (traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b) and one study, electro ‐ Zhang 1987, used electroacupuncture.

7.3.2 TCM drug

Two studies used Fuyuankang capsule (traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b) and one study, electro ‐ Zhang 1987, traditional decoction of herbs ‐ Dang Gui Cheng Qi Tang.

7.4 Acupuncture

The categories of acupuncture were traditional acupuncture (traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b), electroacupuncture (electro ‐ Zhang 1987) and laser acupuncture (laser ‐ Liu 1986; laser ‐ Zhang 1991) with different acupoints.

7.5 Antipsychotics

Eight studies used risperidone ranging from 2 to 10 mg/d (acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005; electro ‐ Cheng 2009; electro ‐ Wang 2005; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Ma 2008; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b). Six studies used chlorpromazine (acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002; electro ‐ Cui 2000; electro ‐ Zhang 1987; laser ‐ Liu 1986; laser ‐ Ma 1999; laser ‐ Zhang 1991). Three studies did not describe more details of antipsychotics used (acupoint cat ‐ Wang 1997; electro ‐ Zhang 2001; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011). Two studies reported using clozapine (electro ‐ Xiong 2010; electro ‐ Yao 2006), one study ‐ electro ‐ Chen 2008 ‐ used aripiprazole and the average dosage was 20.1 ± 4.3 mg/d. The remaining seven studies reported that people remained on previous antipsychotics treatment (acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000; acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; electro ‐ Chen 2006; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; electro ‐ Zhou 1997; traditional ‐ Tang 2005). One study ‐ traditional ‐ Wang 2006 ‐ reported using enough dosage antipsychotics, which was equal to chlorpromazine dosage ranged from 0.4 to 0.6 g/d) and traditional ‐ Xu 2004 reported maximum daily dosage was equivalent chlorpromazine dosage 0.4 to 0.7 g/d.

7.6 TCM drug

Two studies used Fuyuankang capsule (traditional ‐ Zhao 2005a; traditional ‐ Zhao 2005b) and one ‐ electro ‐ Zhang 1987 ‐ used traditional decoction of herbs ‐ Dang Gui Cheng Qi Tang.

7.7 Electric acupuncture convulsive therapy

Only one study, EACT ‐ Xue 1987, reported using acupoints Renzhong and Baihui with average electricity consumption 1.27 Joule.

7.8 Electric convulsive therapy

One study, EACT ‐ Xue 1987, reported using classic electroconvulsive therapy with average electricity consumption 34.97 Joule.

8. Outcomes

8.1 General remarks

Most outcomes of global state, behaviour and adverse effects were dichotomous and trials used a variety of scales. Two studies also reported adding medication outcomes, see Table 7. However some of the scale‐derived data were skewed data and difficult to understand.

1. Other outcomes authors reported.

| Global state: Adding medication | |||

| Study | Drug |

Events/Acupuncture group (n/N) |

Events/Control group (n/N) |

| electro ‐ Cui 2000 | Artane | 6/30 | 11/30 |

| Promethazine | 3/30 | 6/30 | |

| Propranolol | 2/30 | 4/30 | |

| Chlorpheniramine | 0/30 | 1/30 | |

| electro ‐ Wang 2005 | Propranolol | 7/40 | 7/35 |

| Artane | 6/40 | 9/35 | |

| Benzodiazepine drugs | 4/40 | 7/35 | |

| Mental state: Time to auditory hallucinations disappeared (days) | |||

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD |

| laser ‐ Ma 1999 | Laser acupuncture added to standard dose antipsychotics | 19 | 4.1 |

| Standard dose antipsychotics | 31 | 4.4 | |

8.2 Outcomes scales from which it was possible to use data

8.2.1 Global state scales

8.2.1.1 Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI (Guy 1970) The CGI is a three‐item scale commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. The items are: severity of illness, global improvement and efficacy index. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. laser ‐ Zhang 1991 and electro ‐ Zhou 1997 reported CGI data.

8.2.2 Mental state scales

8.2.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The BPRS is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from zero to 126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Thirteen studies reported BPRS data (acupoint inj ‐ Pan 2002; acupoint inj ‐ Yang 2000; electro ‐ Cui 2000; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Xiong 2010; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; electro ‐ Zhou 1997; laser ‐ Ma 1999; laser ‐ Zhang 1991; traditional ‐ Liu 2010; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004). One study, acupoint inj ‐ Wang 2000, only reported the data of the twelfth item of BPRS ‐ hallucinations.

8.2.2.2 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS* (Kay 1986) This is a 30‐item scale, each of which can be defined on a seven point scoring system from absent to extreme. It has three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity. Eight studies reported data using this scale (acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005; electro ‐ Chen 2008; electro ‐ Cheng 2009; electro ‐ Ding 2005; electro ‐ Wang 2005; electro ‐ Yao 2006; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011; traditional ‐ Ma 2008).

8.2.2.3 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms ‐ SAPS (Andreasen 1982) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Five studies reported SAPS data (acupoint cat ‐ Sun 2005; electro ‐ Zhang 1993; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004).

8.2.2.4 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1982) This scale allows a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia (impoverished thinking), affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attention impairment. Assessments are made on a six‐point scale (zero = not at all to five = severe). Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Data for this scale were reported by five studies (electro ‐ Zhang 1993; traditional ‐ Bouhlel 2011; traditional ‐ Luo 2006; traditional ‐ Wang 2006; traditional ‐ Xu 2004).

8.2.2.5 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ‐ HAMD (Hamilton 1967) This instrument is designed to be used only on patients already diagnosed as suffering from affective disorder of the depressive type. It is used for quantifying the results of an interview, and its value depends entirely on the skill of the interviewer in eliciting the necessary information. The scale contains 17 variables measured on either a five‐point or a three‐point rating scale, the latter being used where quantification of the variable is either difficult or impossible. Among the variables are: depressed mood, suicide, work and loss of interest, retardation, agitation, gastro‐intestinal symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, loss of insight, and loss of weight. It is useful to have two raters independently scoring a patient at the same interview. The scores of the patient are obtained by summing the scores of the two physicians. A score of 11 is generally regarded as indicative of a diagnosis of mild depression, 14 to 17 mild to moderate depression and >17 moderate to severe depression. electro ‐ Chen 2006 and electro ‐ Zhang 2001 reported data of this scale.

8.2.2.6 Zung Self‐Rating Depression Scale ‐ SDS (Zung 1965) The Zung Self‐Rating Depression Scale is a 20‐item self‐rated scale that is widely used as a screening tool, covering affective, psychological and somatic symptoms associated with depression. The questionnaire takes approximately 10 minutes to complete and items are framed in terms of positive and negative statements. It can be effectively used in a variety of settings, including primary care, psychiatric clinics, drug trials and various research situations. Each item is scored on a Likert scale ranging from one to four. Most people with depression score between 50 and 69, while a score of 70 and above indicates severe depression. electro ‐ Zhang 2001 reported SDS data.

8.2.2.7 Psychotic symptom rating scale ‐ PSYRHS* (Haddock 1999) Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales is a 17‐item, five‐point scale to rate symptom scores (zero to four) with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. The scales consist of two subscales ‐ the auditory hallucinations subscale (AH) and delusions subscale (DS). The auditory hallucinations subscale is an 11‐item scale. The dimensions of auditory hallucinations are frequency, duration, location, loudness, beliefs re‐origin of voices, amount of negative content of voices, degree of negative content, amount of distress, intensity of distress, disruption to life caused by voices, controllability of voices. The total AH score ranges from zero to 44. The delusions subscale is a six‐item scale. The dimensions of delusions include amount of preoccupation with delusions, duration of preoccupation with delusions, conviction, amount of distress, intensity of distress and disruption to life caused by beliefs. The total DS score ranges from zero to 24. electro ‐ Cheng 2009 reported data of auditory hallucinations subscale (PSYRHS‐AH).

8.2.2.8 Specific Auditory Hallucination Scale ‐ SAHS* (Lu 2006) Specific Auditory Hallucination Scale derives from Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. The scale includes four items of SAPS. The four items are auditory hallucinations, voice commenting, voice conversing, global rating of severity of hallucinations. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Only traditional ‐ Liu 2010 reported SAHS data.

8.2.3 Adverse effects scales