Abstract

In this qualitative study, we explored perspectives of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) and their families on the Get to Know Me board (GTKMB). Of the 46 patients approached, 38 consented to participate. Of the 66 family members approached, 60 consented to participate. Most patients (26, 89%) and family members (52, 99%) expressed that GTKMB was important in recognizing patient's humanity. Most patients (20, 68%) and families (39, 74%) said that it helped to build a better relationship with the provider team. 60% of patients and families commented that the GTKMB was used as a platform by providers to interact with them. Up to 45 (85%) of the family members supported specific contents of the GTKMB. In structured interviews (11 patients, 7 family members), participants additionally commented on ways providers used the GTKMB to communicate, support patient's personhood, and on caveats in interacting with GTKMB. Critically ill patients and families found the GTKMB helpful in preserving personhood of patient, fostering communication, and building relationships with clinicians.

Keywords: Humanization, anonymity, get to know me board, intensive care unit, patient centered care, family centered care

Significance

Preserving personhood is important to critically ill patients and their families. The GTKMB can help preserve personhood of patients and build relationship between patients and their families with their ICU providers. The GTKMB could foster humanized care in the ICU.

Introduction

The experience of critical illness leading to either a path to recovery or imminent death places patients at risk of losing their dignity and respect. 1 The process where someone is deprived of positive human qualities is referred to as dehumanization. 2 Inadequate respect for patient and families in setting of critical illness has previously been brought to attention by families. 3 Loss of identity, with or without the state of delirium, is closely tied to inability to communicate, control environment in state of critical illness, being referred to room numbers or disease entities.4,5 Sequelae of critical illness of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder is present in upto a third of survivors.6–8 Why are ICU experiences so traumatic? We can reflect on what it may be like to be that person who perhaps for the first time in their life truly experienced a real threat of dying. Someone unable to speak, to sleep normally, in pain, stripped naked, with strangers entering the room and doing things to their bodies without explanation, having tubes inserted into multiple orifices, their arms restrained, while hearing a cacophony of disorienting bedside alarms whose meaning lies beyond them. 5 Hallucinations and nightmares are common experiences in the ICU as are feelings of fear, loneliness, uncertainty and thoughts about death.9–11 Memories of frightening and delusional experiences from the intensive care unit (ICU) stay appear to be the strongest potentially modifiable risk factor.6,12–14

An ICU designed to promote thriving, not just surviving, is important for all members of the healthcare team. Survivors of critical illness emphasize the importance of recognition of their individuality, being treated as human beings and not just as a list of ‘medical diagnoses’.15,16 Families of critically ill patients have also stressed the importance of preserving dignity in the intensive care unit (ICU) pointing out value of being treated as ‘person’, ‘human’, ‘individual’, ‘equal’. 15 Loss of dignity and dehumanization are tied to profound emotional and psychological damage. 17 Dehumanization is harmful as it results in erosion of trust, lapses in communication and violation of the relationship between patients, their families, and the providers caring for them.17,18 A recent survey of physicians, patients, and their families demonstrated that inadequate communication was universally viewed as the key problem contributing to patient distress and fear.19,20 This problem further escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when visitor restrictions lead to so many patients being isolated for prolonged periods of time, away from families, often even dying alone. 21 However, efforts of clinicians at providing dignity centered care even during the challenges of the pandemic are most encouraging in their impact on patients and their families. 22

There are indeed frameworks and commentaries on the need to humanize the ICU for patients and families.5,23,24 Focusing on dignity conserving care has been effective at enhancing personhood of patients, thereby improving experiences of patients, families and health care providers. 25

A foundation for dignity conserving care in the ICU comes from the science of palliative medicine: the Get to Know Me Board (GTKMB) concept was originally introduced to elevate patients from anonymity at the end of life.26,27 A standard GTKMB includes patient's nickname, favorite activities, hobbies, likes and dislikes, and information about their relationships and achievements. It offers the opportunity to learn about a patient as a human being, and also provides a valuable foundation to develop a better understanding of their baseline quality of life and goals that can help inform care conversations. 28 Such methods to preserve personhood have demonstrated a significant positive influence on the clinicians’ attitude, compassion, respect, sense of connectedness, and personal satisfaction with providing care.25,29–31 In our institution both patients and families may contribute to the content of the board. 28

It is not known, however, whether the implementation of the GTKMB can positively impact patient-centered outcomes. Our preliminary data from physicians and nurses show widespread support for the GTKMB to restore dignity and humanize critical care; it was felt that GTKMB would be easy to incorporate into practice; responders agreed that it enhanced ability to communicate with patients and families and helped to forge relationships. 28 Nonetheless, lack of provider ownership and competing clinical demands have been barriers to implementation. Could the GTKMB be further optimized? What may be the effective ways for it to become a part of clinical practice, such as prompt better communication? What are the main challenges to its widespread adoption? These questions need to be answered prior to evaluating the full impact of the GTKMB.

In this study, we seek to examine ICU patients’ and their families’ perspectives on the current prototype of the GTKMB: specifically, the value of the board, its current form and content, and potential unintended consequences.

Methods

We performed a prospective qualitative study targeting patients admitted to an ICU in an academic tertiary care center between March 2021 and February 2022. The study, Humanizing the Intensive Care Unit: Perspective of Patients and Families on the Get to Know Me Board was approved by Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Institutional Review Board (IRB # 19-010753, approval date: March 31st, 2020).

Study Population and Data Collection

The survey was administered to adult patients >18 years of age hospitalized in an ICU for more than 24 h who had a GTKMB in place during their stay. Patients were approached when clinically able to participate in the survey where they were able to communicate. This was determined by our research coordinator LF while rounding in the ICUs. For example, patients on mechanical ventilation would be approached when liberated from it and improved. Family members were self-identified and eligible if present at bedside. Because data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, family surveys were conducted once visitor limitations were lifted. Thus, patients and families were not matched, meaning if the patient was not able to participate but a family member was willing, just a family member was enrolled. Patients unable to communicate or non-English speaking were excluded as were the patients at the end of life.

Sample Size

Given the exploratory nature of our study and the inclusion of open-ended questions in our design, we established a targeted accrual between 40 and 50 patients and families per group to achieve thematic saturation and maximize our understanding of patients’ and families’ experiences.

Outcomes

Perspectives of patients and family members on the use of GTKMB in the care of patients during critical illness.

Survey

A survey was developed by SA (MD), LK (MD), LR (PhD, RN), LF (RN) with input from our patient advocate (BA). The final survey was pilot tested in a sample of eight patients and families not enrolled in the current study after content validity was agreed upon by the study team. Survey questions included items discussing content and form of the existing GTKMB; patient family perception of whether the board was used by the providers; impact of the board on the patient/family experiences; and potential negative consequences of using the board.

All surveys were administered by a trained study coordinator (LF) after obtaining oral consent. Following completion of the quantitative portion of the survey, participants were invited to participate in a short, structured interview. The interview questions included:

‘Are there other ways that providers could know your human side?’; ‘Can you share situations where you felt disrespected, alienated, dehumanized?’; and ‘how did you think the board helped your providers?’

Statistical Approach

Demographic data including age, sex, ethnicity, and patient diagnosis, were collected for both patient and family participants; ICU length of stay was collected for patients. Patient and family characteristics, patient outcomes, and responses to patient and family questionnaires were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Data management and statistical analysis were performed in SAS Studio 3.8 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis (Granehejm & Lundman). The de-identified interview was audio recorded and transcribed for analysis using Nvivo.

Results

Survey

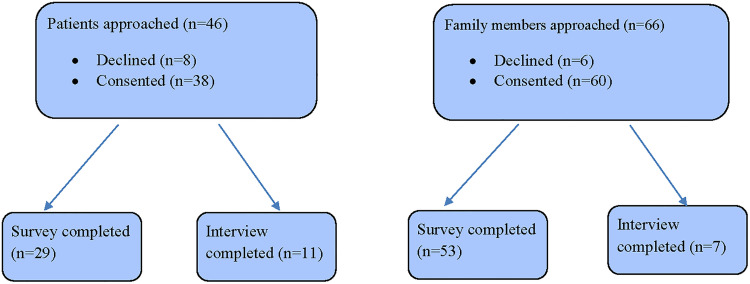

Please see Figure 1 for the number of patients and family members who were approached and completed the study. Demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. COVID-19 pneumonia was observed in nine patients (24%); 58% of patients received invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

Figure 1.

Patient and family enrollment and study completion diagram.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

| Characteristics | Patient (n = 38) | Family (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 59 (47, 69) | 57 (48, 65) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 15 (39%) | 17 (32%) |

| Male | 23 (61%) | 36 (68%) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Black | 1 (3%) | - |

| White | 28 (93%) | - |

| Other | 1 (3%) | - |

| Type of ICU, n (%) | ||

| Surgical | 5 (13%) | - |

| Medical | 17 (45%) | - |

| Cardiac | 4 (11%) | - |

| Trauma | 2 (5%) | - |

| Mixed | 10 (26%) | - |

| Positive COVID-19 test, n (%) | 9 (24%) | - |

| Relation to patient, n (%) | ||

| Spouse/Partner | - | 26 (50%) |

| Child | - | 10 (19%) |

| Parent | - | 8 (15%) |

| Sibling | - | 6 (12%) |

| Friend | - | 1 (2%) |

| Nephew/Niece | - | 1 (2%) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| High school | - | 12 (23%) |

| Some college | - | 16 (31%) |

| College or more | - | 24 (46%) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Hospital LOS in days, median (IQR) | 23 (8, 32) | - |

| ICU LOS in days, median (IQR) | 14 (6, 23) | - |

| Any ventilation, n (%) | 22 (58%) | - |

| Non-invasive ventilation, n (%) | 12 (40%) | - |

| Invasive ventilation, n (%), N = 31 | 13 (45%) | - |

| Vasopressors or inotropes, n (%) | 23 (61%) | - |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 3 (8%) | - |

IQR = interquartile range; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay.

Twenty-nine patients and 49 (92%) family members recalled presence of the GTKMB. 69% of patients and 77% of family members participated in filling out the board. Most patients (26, 90%) and family members (52, 99%) felt it was important for the ICU care team to get to know the human side of the patient. Both patients (68%) and family members (74%) indicated the GTKMB board helped to build a relationship with the ICU care team on a more personal level all or most of the time. Whereas a few family members indicated concern with privacy with features of the GTKMB, most patients (27, 93%) and families (48, 91%) did not find any of the existing features intrusive. Please see Table 2 for full survey results.

Table 2.

Survey Results from Patient and Family Perspectives on the Get to Know Me Board.

| Feedback on Use of the Get to Know Me Board | Patient (n = 29) | Family (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| Recalled the presence of the Get to Know me Board in room | 29 (100%) | 49 (92%) |

| Participated in filling out of the Get to Know Me Board | 20 (69%) | 36 (77%) |

| Importance of the ICU care team getting to know the human side of the patient | ||

| Extremely important | 13 (45%) | 27 (51%) |

| Very important | 7 (24%) | 21 (40%) |

| Important | 6 (21%) | 4 (8%) |

| Somewhat important | 2 (7%) | 1 (2%) |

| Not at all important | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| How did the ICU care team use the information from the Get to Know Me Board? | ||

| Most providers interacted with me using the information | 10 (35%) | - |

| Some providers interacted with me using the information | 9 (31%) | - |

| Rarely anyone interacted with me using the information | 1 (3%) | - |

| No one interacted with me using the information | 5 (17%) | - |

| Unsure | 4 (14%) | - |

| Perspectives on communication experience | ||

| Did the Get to Know Me Board interfere with your medical care? | ||

| All of the time | 1 (3%) | - |

| Most of the time | 1 (3%) | - |

| Some of the time | 1 (3%) | - |

| None of the time | 26 (90%) | - |

| Get to Know Me Board helped me to: | ||

| Build a relationship with the ICU care team on a more personal level | ||

| All of the time | 10 (34%) | 19 (36%) |

| Most of the time | 10 (34%) | 20 (38%) |

| Some of the time | 6 (21%) | 9 (17%) |

| None of the time | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unsure | 0 (0%) | 5 (9%) |

| Feel more comfortable with the care | ||

| All of the time | 13 (45%) | 21 (40%) |

| Most of the time | 9 (31%) | 21 (40%) |

| Some of the time | 3 (10%) | 5 (9%) |

| None of the time | 2 (7%) | 2 (4%) |

| Unsure | 2 (7%) | 4 (8%) |

| Overcome fear or anxiety | ||

| All of the time | 6 (21%) | 7 (13%) |

| Most of the time | 9 (31%) | 17 (32%) |

| Some of the time | 4 (14%) | 20 (38%) |

| None of the time | 3 (10%) | 3 (6%) |

| Unsure | 7 (24%) | 6 (11%) |

| Which members of your treatment team communicated with you in a way that made you feel heard and/or understood?* | ||

| Doctor | 24 (83%) | 44 (83%) |

| Nurse practitioners/Physician assistants | 25 (86%) | 45 (85%) |

| Nurse | 17 (59%) | 37 (70%) |

| Physical/Occupational therapist | 15 (52%) | 31 (58%) |

| Respiratory therapist | 20 (69%) | 32 (60%) |

| Chaplain/social worker | 12 (41%) | 30 (57%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 7 (13%) |

| No one | 3 (10%) | 3 (6%) |

| What best describes your experience with the Get to Know Me Board?* | ||

| Providers used information to talk to the patient | - | 32 (60%) |

| Providers used information to talk to me | - | 32 (60%) |

| Made it easier for the patient to ask questions of the treatment team | - | 9 (17%) |

| Providers rarely used information to talk to the patient | - | 3 (6%) |

| Providers rarely used information to talk to my family member | - | 3 (6%) |

| Did not make it easier for the patient to ask questions of the treatment team | - | 2 (4%) |

| Unsure | - | 4 (8%) |

| Perspectives on format/privacy | ||

| Helpful for the providers to know about the patient as a person* | ||

| Name, nickname | 8 (28%) | 45 (85%) |

| Favorite movies, TV shows, books, music, sports, food, pet(s) | 6 (21%) | 41 (77%) |

| Activities and hobbies | 6 (21%) | 43 (81%) |

| Achievements | 2 (7%) | 37 (70%) |

| Things that can stress the patient out or cheer them up | 7 (24%) | 44 (83%) |

| None of these | 20 (69%) | 1 (2%) |

| Types of information that may endanger privacy of the patient* | ||

| Name, nickname | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) |

| Favorite movies, TV shows, books, music, sports, food, pet(s) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Activities and hobbies | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Achievements | 1 (3%) | 2 (4%) |

| Things that can stress the patient out or cheer them up | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

*Check all that apply; ICU = intensive care unit.

While there were many comments shared by patients and families with positive feedback on features of GTKMB, at least 2 family members shared that there was inadequate or no interaction with the board by the providers. Also, one family member pointed out the unfavorable location of the board in the room. See Table 3 for specific feedback.

Table 3.

Additional Feedback from Patients and Family Members on the Get to Know Me Board.

| Patient Perspectives | |

|---|---|

| Reminded providers of patient's human side |

|

| A welcome distraction |

|

| Family Members’ Perspectives | |

| Making connections |

|

| Used by Family to Support the Patient's recovery |

|

| Other comments from survey | |

| 1. Inadequate/absent interaction with GTKMB- Family |

|

Interview

Representative interview quotes are displayed in Table 3. Comments from 11 patients and 7 family members confirmed the value of the GTKMB in learning the human side of the patient. Family members noted that the board offered an opportunity to establish a connection between the patient and their caregivers. Specific things that are important to the patients were described by family members as ways to build trust and start a conversation. Family members described not only the value of the board to the patient, but also to themselves. Having something to focus on, including the unique characteristics or stories about the family members, validated family's input. The use of the board by family members also included knowing who the team members were and helped them feel connected to the care team.

Patients, in general, did not recall much about their ICU stay and thus were more neutral about the board than family members. Those patients who were able to recall the GTMKB indicated that filling out the board provided a distraction from the critical illness. Patients felt that the board allowed for a way for their story to be told and provided a foundation for conversation and connection. A key humanizing factor and outcome of the GTKMB emphasized by both patients and their family members was the importance of using the patient's preferred name which was enhanced by the presence of the GTKMB.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the GTKMB is largely perceived as a valuable tool for preserving personhood for the critically ill patients, even for those not at the end of life. Most patients and families found that the GTKMB helped to emphasize them as individuals and recognize their human aspect. Families could rely on the GTMKB to humanize the patient at a time when visitors were restricted or limited. Using ‘patient's preferred name’ was deemed especially important by both patients and their families as a key humanizing factor in patient centered care. Minor concerns for intrusion in patient privacy in the survey were clarified in analysis of the structured interviews; overall there was no adverse impact on patient privacy as seen by the participants. Additional concern included GTKMB not being used by the staff even when filled out.

Whereas the call for recognizing a patient's personhood has been previously made for serious diseases like advanced malignancy, patients with dementia, and those at the end of life,25,30,31 findings from this study have implications for those expected to survive critical illness. Recognizing personhood as an aspect of humanized caring is one of the interventions to promote patient and family centered caring in the ICU, and can enable providing compassionate and respectful care.32,33 Asserting personhood is one of the key priorities identified by patients in the post-ICU recovery period. 34 The GTKMB made its way into the intensive care unit following recognition of the unmet need of palliative care in the critically ill near end of life to uplift patient from anonymity.26,27 Another strategy implemented in the literature has been developing the Patient Dignity Question (PDQ), which includes the questions ‘what do I need to know about you as a person to give you the best possible care?’ 25 Similar to our findings, most patients and families reported the PDQ to be accurate and to provide information important for care providers to know. They also considered recommending PDQ to others and consented to place the PDQ summary interview in the medical chart. 25 This concept has further grown to include the ‘Footprints project’ focused on personalizing care for patients at the end of life with emphasis on personhood. 29 The Footprints project has similar elements to the GTKMB. It was found to help humanize the experience of patients, enable conversations with patients and families, enhance inter-disciplinary communication and have a favorable impact on provider stress/ burnout in caring for seriously ill patients. Another similar tool to the GTKMB has been the This Is ME (TIME) questionnaire used for elderly residents of nursing homes. 30 The ability to foster conversations and build relationships between care providers and patients and families using methods to elicit personhood is consistent with the patient/family perspectives in this study.

This study of the GTKMB brought to light the views of patients who survived a critical illness and their families. While the GTKMB and similar strategies have been of value for those at end of life, patients who survive critical illness are just as likely to suffer from loss of identity. Deficits in function, cognition, and mental health such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, collectively called post-ICU syndrome (PICS), are common outcomes in survivors of critical illness. 35 How providing humanized or patient centered care to critically ill patients could impact some of these longer-term outcomes will be an area of interest in future studies.

In the effort to prevent delirium in the ICU, the A-F bundle in the ICU is expanding to include a focus on preserving human dignity. 36 Bundle authors are looking to expand it in the future with three additional letters, incorporating humanitarian care: gaining (G) insight into patient needs, delivering holistic care with a ‘home-like’ (H) environment, and redefining ICU architectural design (I). 37 A Patient Dignity Inventory, a 25-item instrument, 23 has been validated in the ICU for those with terminal illness to assess for patient distress with psychological sequelae. 38 The call to humanize care in the ICU environment also includes gaining insight into patient preferences, habits at home and pre-morbid lifestyle.24,37 The potent impact of eliciting personhood on the short- and long-term experience of critical illness was described by one of our survivors of critical illness with disability, speech impairment, and critical illness. 39 Using tools that can remind care providers of patients as human beings beyond the specific ailment and allow providers to connect with patients and families on a human level may moderate the stress of critical illness. Humanizing strategies such as calling the patient by their preferred name can be employed during the routines of patient care, and communication with patients, including those who have decreased consciousness or cognitive impairment. Gaining insight into patient needs using strategies that included the use of the GTKMB was extremely successful in individualizing care and developing a Recovery Checklist for a survivor of COVID related critical illness. 40

Moreover, fast paced technology-dominated environment combined with high levels of patient morbidity and mortality, ethical dilemmas, uncertainty of prognoses, conflicts, end of life care and decisions on foregoing life- sustaining therapies, high workload, and shift work often culminates in clinician burnout and moral distress.5,24,41–44 Feelings of anger, exhaustion, frustration, powerlessness, depersonalization, and detachment translate to patients being referred by their disease or room number, absence of empathy, violations of respect and dignity, and dehumanization. 1 Since prior efforts to elicit personhood have revealed a positive impact on clinician attitude towards caring and respect for patients at end of life as well as on work satisfaction,25,29–31 the effect of integrating the GTKMB in ICU workflow on provider burnout will also be an area of interest in future trials.

The study has several limitations. First, it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when strict visitor restrictions were in place for patients with and without COVID-19 infection. This did result in challenges with recruitment of patients and family members. Second, implementation of the GTKMB was not consistently adhered to in practice and especially when the ICU workload was excessive; this may be a reason why providers sometimes did not interact with the GTKMB in patient/family communication. Third, investigators developed the survey instrument in this study, but this instrument is not a validated measurement tool. A semi-structured interview was originally intended, though it ended up being structured to facilitate the brevity of the interviews as many patients exhibited fatigue with longer interactions.

The study strength include confirmation that preserving personhood is a key element of care for critically ill patients irrespective of their survival status, as we observed in the responses of patients and families. The GTKMB, if implemented among strategies to humanize ICU care,24,45 may have significant bearing on patient and family centered care in the ICU, their experience, communication in the ICU and potentially provider wellbeing.

Conclusion

Preservation of dignity and respect for patients needs to be revived in its niche in medicine. As Dr Francis Weld Peabody eloquently stated, “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient”. 46 More qualitative work is being pursued to explore perspectives of ICU providers on the GTKMB. This study serves to lay the foundation for more rigorous studies including randomized control trials to evaluate the impact of integrating the GTKMB into the care of critically/ seriously ill patients on patient centered outcomes, family experience and provider burn out.

Acknowledgements

Mr. Ben Anderson, Patient Advocate.

Abbreviations

- GTKMB

Get to Know Me board

- ICU

-

Intensive care unit

Humanization

Abstract Presentation: Society of Critical Care Medicine Congress, San Francisco January 2023.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Zoll Foundation Award 2020, (grant number FP00113444).

ORCID iD: Sumera R. Ahmad https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0225-3330

References

- 1.Brown SM, Azoulay E, Benoit D, et al. The practice of respect in the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(11):1389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galvin IM, Leitch J, Gill R, Poser K, McKeown S. Humanization of critical care-psychological effects on healthcare professionals and relatives: a systematic review. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65(12):1348–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law AC, Roche S, Reichheld A, et al. Failures in the respectful care of critically ill patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2019;45(4):276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hume VJ. Delirium in intensive care: violence, loss and humanity. Med Humanit. 2021;47(4):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson ME, Beesley S, Grow A, et al. Humanizing the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1744–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topçu S, Alpar S, Gülseven B, Kebapçı A. Patient experiences in intensive care units: a systematic review. Patient Experience Journal. 2017;4(3):115–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kentish-Barnes N, Degos P, Viau C, Pochard F, Azoulay E. “It was a nightmare until I saw my wife”: the importance of family presence for patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(7):792–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magarey JM, McCutcheon HH. ‘Fishing with the dead'–recall of memories from the ICU. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2005;21(6):344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wade DM, Brewin CR, Howell DC, White E, Mythen MG, Weinman JA. Intrusive memories of hallucinations and delusions in traumatized intensive care patients: an interview study. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(3):613–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wintermann GB, Rosendahl J, Weidner K, Strauss B, Petrowski K. Risk factors of delayed onset posttraumatic stress disorder in chronically critically ill patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(10):780–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Skirrow PM. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(3):573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beach MC, Forbes L, Branyon E, et al. Patient and family perspectives on respect and dignity in the intensive care unit. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2015;5(1a):15a–25a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickert NW, Kass NE. Understanding respect: learning from patients. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(7):419–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sokol-Hessner L, Folcarelli PH, Sands KE. Emotional harm from disrespect: the neglected preventable harm. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(9):550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell SK, Roche SD, Mueller A, et al. Speaking up about care concerns in the ICU: patient and family experiences, attitudes and perceived barriers. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(11):928–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dziadzko V, Dziadzko MA, Johnson MM, Gajic O, Karnatovskaia LV. Acute psychological trauma in the critically ill: patient and family perspectives. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karnatovskaia LV, Johnson MM, Dockter TJ, Gajic O. Perspectives of physicians and nurses on identifying and treating psychological distress of the critically ill. J Crit Care. 2017;37:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson-Shaw LK, Zar FA. COVID-19, moral conflict, distress, and dying alone. J Bioeth Inq. 2020;17(4):777–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ely EW. Each person is a world in COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):236–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(6):559–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velasco Bueno JM, La Calle GH. Humanizing intensive care: from theory to practice. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2020;32(2):135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, Thompson G, Dufault B, Harlos M. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):974–80.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: description of an intervention. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. Merging cultures: palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad S, Gajic O, Karnatovskaia LV. Humanizing care in the intensive care unit: Perspectives of clinicians on using the Get to Know Me board. ESICM LIVES; 2019-Abstract presentation; Berlin.

- 29.Hoad N, Swinton M, Takaoka A, et al. Fostering humanism: a mixed methods evaluation of the footprints project in critical care. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e029810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan JL, Chochinov H, Thompson G, McClement S. The TIME questionnaire: a tool for eliciting personhood and enhancing dignity in nursing homes. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(4):273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fick DM, DiMeglio B, McDowell JA, Mathis-Halpin J. Do you know your patient? Knowing individuals with dementia combined with evidence-based care promotes function and satisfaction in hospitalized older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(9):2–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herridge MS, Azoulay E. Outcomes after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(10):913–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Secunda KE, Kruser JM. Patient-Centered and family-centered care in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2022;43(3):539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheunemann LP, White JS, Prinjha S, et al. Post-Intensive care unit care. A qualitative analysis of patient priorities and implications for redesign. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(2):221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotfis K, van Diem-Zaal I, Roberson SW, et al. The future of intensive care: delirium should no longer be an issue. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mergler BD, Goldshore MA, Shea JA, Lane-Fall MB, Hadler RA. The patient dignity inventory and dignity-related distress among the critically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(3):359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gajic O, Anderson BD. Get to know me” board. Crit Care Explor. 2019;1(8):e0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stantz A, Emilio J, Ahmad S, et al. An individualized recovery task checklist which served as an educational instrument in a critically ill and intubated COVID-19 patient. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13():21501319221116249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramírez-Elvira S, Romero-Béjar JL, Suleiman-Martos N, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and burnout levels in intensive care unit nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carnevale FA. Moral distress in the ICU: it's time to do something about it!. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020;86(4):455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(5):482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. Jama. 2001;286(23):3007–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nin Vaeza N, Martin Delgado MC, Heras La Calle G. Humanizing intensive care: toward a human-centered care ICU model. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(3):385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oglesby P. The caring physician: the life of Dr. Francis W. Peabody. Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine; 1991. [Google Scholar]