Abstract

Evidence suggests that individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms exhibit deficits in positive internal experiences. This study critically reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions to determine (1) whether positive memories, cognitions, and emotions were explicitly addressed and (2) the goals of focusing on these positive internal experiences. We selected 11 empirically validated PTSD interventions listed as “recommended/strongly recommended” in recently published reviews, reviewed existing literature for studies using these interventions (N = 1,070), short-listed randomized controlled trial studies meeting predetermined inclusion criteria for the selected interventions (in English, developed for adults, individual therapy modality, in-person administration, tailored to PTSD; N = 47), and emailed authors (N = 41) to obtain the unique intervention manuals. Hereby, we reviewed 13 unique empirically validated PTSD intervention manuals. Findings indicated 53.85%, 69.23%, and 69.23% of reviewed manuals explicitly discussed positive memories, emotions, and cognitions, respectively. Primarily, positive memories were integral to mechanisms underlying PTSD, a precursor to targeting negative experiences, an indicator of treatment progress, or a way to identify client problems; positive emotions were discussed when providing psychoeducation on PTSD/trauma reactions; and positive cognitions were addressed in reference to coping with negative experiences or as targets to enhance self-concept. This review demonstrates that comparatively, positive memories are infrequently elicited in the reviewed interventions; positive emotions and cognitions are explicitly referenced in two-thirds of the reviewed interventions but are included as a primary focus for therapeutic processing only in a few interventions; and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing has the most comprehensive focus on positive internal experiences.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder, intervention review, positive memories, positive emotions, positive cognitions

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by symptoms etiologically linked to the experience of a trauma: intrusive experiences connected to the trauma, avoidance of internal and external reminders of the trauma, negative alterations in cognitions and mood that occur or worsen after the trauma, and alterations in arousal and reactivity that start or worsen following the trauma (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Such symptoms have detrimental psychological and physical health consequences (Schnurr et al., 2009; Zatzick et al., 1997); thus, effective treatments for PTSD have been of significant research priority. Evidence indicates that individuals are less likely to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD than wait-list controls following treatment (44%–66%; Cusack et al., 2016; Schnurr, 2017). However, only about half of those receiving treatment experience a PTSD diagnosis remission (Resick et al., 2002), and existing treatments (trauma-focused in particular) have moderate-to-high dropout rates (19%–68%; Garcia et al., 2011; Hembree et al., 2003). Thinking outside the typical treatment box and incorporating other potentially effective treatment components or targets may improve PTSD intervention outcomes. To this end, this study critically reviewed the extent to which empirically validated PTSD interventions target positive internal experiences.

Positive internal experiences, for the purposes of the current review, reference subjective experiences of positively-valenced and pleasant memories, cognitions, and emotions. Evidence indicates that trauma/PTSD severity is associated with (1) deficits in positive memory recall, access, and other processes (Contractor, Banducci, et al., 2019; Contractor, Banducci, et al., 2020; Harvey et al., 1998; McNally et al., 1995; Megías et al., 2007; Sutherland & Bryant, 2005); (2) a predominance of negative and reduced positive cognitions (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006; Foa & Kozak, 1986; Janoff-Bulman, 1992) worsened by attentional biases toward negative information/memories (Aupperle et al., 2012; Fani et al., 2012; McNally et al., 1995) and rumination on negative memories prompted by trauma reminders (Ehlers & Clark, 2000); and (3) difficulties experiencing, expressing, and/or regulating intense positive emotions (Litz et al., 2000; Weiss, Contractor, Forkus, et al., 2020; Weiss, Contractor, Raudales, et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2018; Weiss, Nelson, et al., 2019). Indeed, disturbances in positive internal experiences are at least one of the diagnostic symptoms (D7) of PTSD’s negative alterations in cognitions and mood cluster (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, strong evidence links deficits in positive internal experiences to PTSD symptomatology.

Indeed, there are beneficial impacts of addressing positive internal experiences in treatment for PTSD. A therapeutic focus on positive memories may improve (a) mood by increasing positive affect and decreasing negative affect, (b) cognitions about self and others, (c) the ability to recall additional positive memories, (d) the therapeutic alliance, and (e) attitudes toward seeking trauma-focused treatments in the future (Contractor, Banducci, et al., 2019; Contractor et al., 2018; Quoidbach et al., 2015; Rusting & DeHart, 2000). The consequent increase in positive emotions may have additional health benefits: protective biological responses (e.g., decreased cortisol); positive health behaviors (e.g., increased physical activity); and improved social support, coping styles, mental health, and success in several life domains (reviewed in Fredrickson, 2000; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Steptoe et al., 2009). Additionally, positive emotions may further activate and increase positive interpretations of events and pleasant thoughts/memories (mood congruency effect; Blaney, 1986; Rusting & DeHart, 2000; Rusting & Larsen, 1998) and increase positive content in thoughts and behaviors (broaden-and-build theory; Fredrickson, 2001). Notably, intervention research indicates beneficial impacts of targeting positive memories (Callahan et al., 2019; Moradi et al., 2014) and emotions (Panagioti et al., 2012) for PTSD.

Despite this theoretical and empirical evidence linking positive internal experiences to PTSD symptomatology, no study to our knowledge has critically examined the extent to, and the manner in, which positive internal experiences are incorporated into existing empirically validated PTSD interventions. To this end, we reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions to determine (1) whether positively valenced and pleasant memories, cognitions, and emotions were addressed and, for those treatments that targeted positive internal experience(s), (2) the goals of addressing these experience(s). The overarching goal of this review was to highlight ways to integrate and capitalize on positive internal experiences while simultaneously reducing negative internal experiences as a part of PTSD interventions.

Method

Selection of PTSD Intervention Manuals

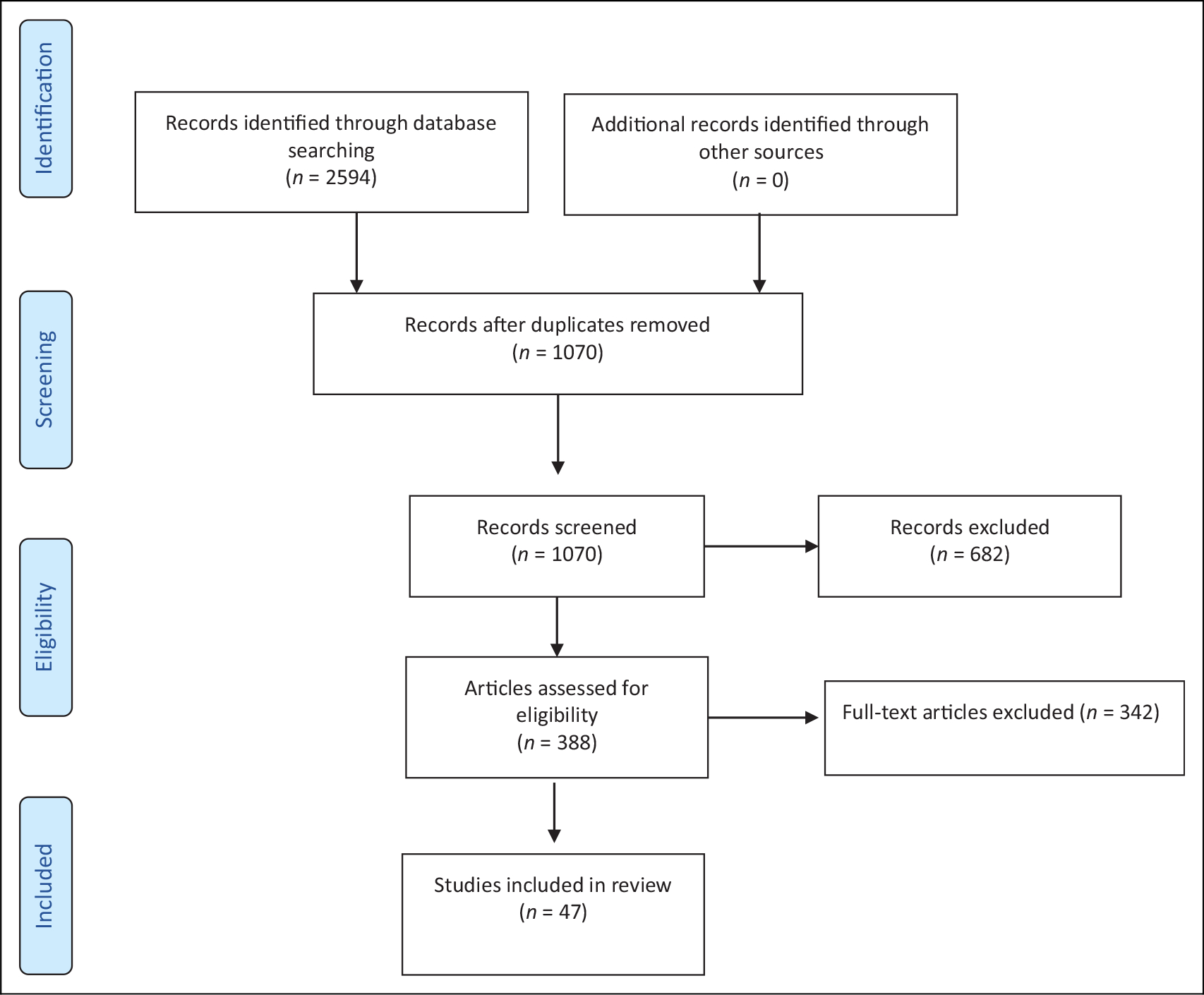

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for the review procedure. At Step 1, we began with 11 empirically validated PTSD interventions listed as “strongly recommended” and “recommended” according to a recent review by Watkins et al. (2018), which drew from the Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group recommendations (2017) and the American Psychological Association guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2017). The selected PTSD interventions included cognitive therapy (CT; Ehlers & Wild, 2015), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2004; Mueser et al., 2008), cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick et al., 2008), prolonged exposure (PE; Foa et al., 2007), written exposure therapy (WET; Sloan & Marx, 2019), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR; Shapiro, 2017), brief eclectic psychotherapy for PTSD (BEPP; Gersons et al., 2011), narrative exposure therapy (NET; Schauer et al., 2011), stress inoculation training (SIT; Foa et al., 1999), present-centered therapy (PCT; Bernardy et al., 2003; Foa et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2011), and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT; Markowitz, 2017).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the review procedure (Steps 2–3 of the outlined procedure).

At Step 2, to ensure capturing all the unique manuals of these interventions (particularly those with greater variation in use such as CBT and CT), one author (S.R.F.) searched the following databases on February 5, 2019: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, PILOTS, and CINAHL. Search terms included the following: “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” OR “Cognitive Processing Therapy” OR “Prolonged Exposure” OR “Cognitive Therapy” OR “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing” OR “Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy” OR “Narrative Exposure Therapy” OR “Written Exposure Therapy” OR “Stress Inoculation Training” OR “Present Centered Therapy” OR “Interpersonal Psychotherapy” AND “randomized controlled trial” AND “PTSD.” A total of 2,594 studies were obtained at this step; after removing duplicates, 1,070 studies remained.

At Step 3, two trained research assistants compiled the studies obtained from Step 2 into a database and screened them to determine whether they met criteria for a randomized controlled trial (RCT; N = 388). Next, two authors (A.A.C. and N.H.W.) screened the eligible studies to determine whether they met the five predetermined criteria: (1) in English, (2) developed for adults, (3) used an individual therapy modality (e.g., vs. group/dyadic modality), (4) administered in-person (vs. developed as an internet- or telephone-based treatment), and (5) tailored to individuals identified by PTSD rather than by PTSD with other co-occurring conditions. The final number included 47 articles.

At Step 4, two of the authors (A.A.C. and N.H.W.) emailed the first author of these shortlisted articles to request the intervention manual used in that respective study (with the exception of the studies utilizing PE or CPT, as the authors of the current review had copies of these treatment manuals). We contacted 41 unique authors once by email; 48.78% of contacted authors responded providing the intervention manuals or information on the requested intervention manuals. In this process, we obtained 18 intervention manuals: three EMDR, five CBT, two BEPP, two IPT, one SIT, one WET, one NET, and three PCT. We excluded two CBT manuals that were not in English, removed duplicates from these obtained manuals, and added the PE and CPT manuals to the list, resulting in a total of 13 PTSD intervention manuals.

At Step 5, two authors (S.R.F. and F.K.) coded each of the intervention manuals for (1) types of positive internal experiences that were directly and explicitly targeted as part of the therapeutic process, and (2) goals of focusing on positive internal experiences (if applicable). During the coding process, these authors extracted and reviewed content specifically tailored to search terms such as “positive,” “thought,” “feeling,” “emotion,” “sensation,” and “memory.” Two authors (A.A.C. and N.H.W.) cross-checked a random 20% of the intervention manuals to ascertain the reliability of the extracted information. Next, two authors (A.A.C. and N.H.W.) read all the short-listed manuals in entirety with a primary focus on the extracted data. Concerns and discrepancies were discussed in an iterative manner throughout the process.

Descriptions of Reviewed PTSD Intervention Manuals

CBT combines cognitive and behavioral techniques to target distressing emotions by modifying maladaptive cognitions and behaviors. CBT consists of approximately 8–12 weekly sessions, each lasting 50–90 minutes (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2004; Mueser et al., 2008). For this review, three unique CBT manuals were coded (i.e., Helping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment [HOPE] Manual, CBT for PTSD, and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy [TARGET]).

CPT draws from social, cognitive, and information-processing theories of PTSD; activates trauma memories; and elicits information to confront the maladaptive beliefs/attributions that cause and maintain PTSD symptomatology (Resick & Schnicke, 1993). CPT primarily consists of psychoeducation; cognitive restructuring including a detailed, written account of the trauma (optional) and Socratic questioning addressing beliefs about and interpretations of the trauma; and enhancement/reinforcement of learned CT skills. CPT typically consists of 12 weekly sessions, each lasting 60–90 minutes (Resick et al., 2008).

PE is an exposure-based treatment that draws from the emotional processing theory of PTSD. PE involves gradually approaching distressing/avoided trauma-related memories, feelings, thoughts, and situations by confronting the trauma memory via repeated in vivo and imaginal exposure. In this process, trauma-related fears and anxieties are reduced via extinction. PE typically consists of 9–12 weekly sessions, each lasting 60–120 minutes (Foa et al., 2007).

WET also draws from the emotional processing theory of PTSD. During WET, participants receive psychoeducation regarding the development and maintenance of PTSD symptoms, and information on the treatment rationale. Participants then write detailed accounts of their trauma. WET typically consists of five weekly sessions, each lasting 40–60 minutes (Sloan & Marx, 2019).

EMDR is based on the adaptive information-processing model. EMDR involves identifying the target trauma memory and assessing its components, desensitization to this trauma memory by recalling a negative thought/memory while experiencing bilateral stimulation, installation of positive cognitions, body scan, and debriefing. EMDR typically consists of 6–12 weekly/bi-weekly sessions, each lasting 60–90 minutes (Shapiro, 2017).

BEPP draws from cognitive, behavioral, and psychodynamic intervention techniques. BEPP includes psychoeducation regarding treatment rationale and PTSD development/symptomatology, relaxation and imaginal exposure, writing assignments and mementos to elicit trauma-related emotions, a focus on meaning and integration, and a farewell ritual. BEPP typically consists of 16 weekly sessions, each lasting 60 minutes (Gersons et al., 2011).

NET draws from principles of exposure and testimony therapies (Neuner et al., 2004). NET involves psychoeducation about PTSD symptomatology and the treatment rationale. Clients then develop a chronological narrative of their entire life with a focus on traumatic experiences. The therapy typically consists of 4–10 weekly or semi-weekly sessions, each lasting 60–120 minutes (Schauer et al., 2011).

SIT draws from cognitive-behavioral approaches to teach clients coping strategies to better manage stress. SIT incorporates relaxation, breathing, cognitive restricting, guided self-dialogue, and role-play. SIT typically consists of 10–14 weekly sessions, each lasting 60–90 minutes (Foa et al., 1999). The manual reviewed for this study is a combination of SIT and PE; we reference only the SIT components for this manual given its overlap with the PE manual reviewed independently.

PCT draws from several crisis intervention models that emphasize mastery of current difficulties. PCT’s components include psychoeducation on the impact of symptoms on daily functioning, problem-solving to address daily challenges, and homework to monitor stressors and practice problem-solving skills. PCT typically consists of 10 sessions, each lasing 90 minutes (Bernardy et al., 2003; Foa et al., 2010). We reviewed another unique PCT manual (Ford et al., 2011) that uses 16 sessions, each lasting 50 minutes; is specifically tailored to survivors of childhood sexual abuse; and focuses on resolving interpersonal difficulties.

IPT draws from interpersonal and attachment-based theories. The core assumption of IPT is that trauma disturbs one’s interpersonal environment, and suffering can be alleviated by improving social/interpersonal functioning. IPT generally consists of 12–16 weekly sessions, each lasting 60 minutes in the acute phase of treatment, occasionally followed by a continuation of IPT or a “maintenance phase” (Markowitz, 2017).

Results

Positive Memories

Discussion of positive memories. Overall, 53.85% of intervention protocols had an explicit discussion of positive memories; they were CPT, CBT TARGET, EMDR, BEPP, PCT (Ford et al., 2011 Version), NET, and IPT (see Table 1).

Goals of focusing on positive memories.

Table 1.

Summary of Positive Internal Experiences Addressed in Reviewed PTSD Interventions.

| Treatment Protocol | Type(s) of Positive Internal Experiences | Goals of Addressing Positive Internal Experiences |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for PTSD (Gersons et al., 2011) | Positive memories, positiveemotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: Positive memories are potential targets for imaginal exposure if clients are too tense despite relaxation exercises or are afraid of experiencing trauma memories. Positive emotions: Positive emotions are potentially addressed within the transference context (i.e., identifying positive emotions andexploring their origin). Such transference may play an implicit therapeutic role wherein clients may draw connections between trauma and other experiences. Positive cognitions: Positive cognitions are targets in the meaning and integration phase; they are referenced as the development of a new (likely realistic and positive) sense of self. |

| Prolonged Exposure (Foa et al., 2007) | NA | NA |

| Stress Inoculation Therapy (Foa et al., 1999) | Positive cognitions | Positive cognitions: Positive self-statements and self-talk are addressed as coping strategies tailored to four categories—preparing for a stressor, confronting and handling a stressor, coping with being overwhelmed, and reinforcing self-statements. |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT; Mueser et al., 2008) | Positive cognitions | Positive cognitions: Positive self-talk and self-statements are addressed as part of coping strategies for intrusion symptoms, nightmares, and anger-provoking situations (characteristic of PTSD). |

| CBT Helping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment (HOPE) Manual (Johnson et al., 2004) | Positive emotions, positivecognitions | Positive emotions: Lack of positive emotions are discussed in the context of PTSD’s emotional numbing symptoms. Therapist examines negative impact of emotional numbing, conducts a functional analysis of emotional numbing, and addresses coping with emotional numbing (e.g., use of empowerment tools vs. numbing). Positive cognitions: Positive affirmations, as empowerment tools, are used to rethink survivor thoughts and to self-soothe. Positive self-talk is used to cope with triggers. Positive coping statements are discussed as grounding techniques. |

| CBT Therapy for Adaptive Relationships, Growth, and Empowerment after Traumatic Stress (TARGET) Manual (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011) | Positive memories, positiveemotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: Positive memories are discussed in the context of one of the FREEDOM skills of identifying triggers for stressful reactions (may be positive events/changes). Positive memories are addressed as part of the Life Book exercise wherein clients create a picture of their life by including information on important (including positive) events, individuals, and issues. Last, positive memories are discussed in the context of one of the FREEDOM skills of making a contribution; the therapist elicits a memory of how clients made a positive difference in the stressful situation and clients also add this component to their Life Book. Positive emotions: Positive emotions are discussed in the context of treatment goals; the therapist indicates that using the FREEDOM skills effectively can result in positive feelings. Positive emotions are discussed in the context of the FREEDOM skill of evaluating main (vs. reactive) thoughts occurring during stress reactions; positive emotions may be triggered by one’s interpretation of events via thoughts. Positive cognitions: Positive cognitions are addressed as one of the treatment goals, which is to help clients develop a positive sense of identity. The positive cognition-related component of positive self-image is addressed in psychoeducation when explaining how the brain and body are impacted by extreme stress. Last, positive cognition-related components are addressed in the FREEDOM skills of making a contribution; the therapist encourages the client to elicit a memory of how they made a positive difference in a stressful situation that enables them to build a sense of true worth. |

| Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT; Markowitz, 2017) | Positive memories, positive emotions | Positive memories: In the middle phases, therapist elicits memories of affectively charged incidents including positive situations. Positive emotions: In the middle phases, therapist focuses on interpersonal problem areas such as grief, role transition, role dispute, or interpersonal deficits to improve interpersonal functioning. Referencing IPT for grief, clients are encouraged to explore and express negative and positive feelings toward the person they have lost. By not intervening and/or interrupting the expression of emotions, clients understand that the feelings are tolerable and transitional. |

| Cognitive Processing Therapy (Resick et al., 2008) | Positive memories, positive emotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: Positive memories of lost loved ones as triggered by holidays/celebration are discussed. The conflict between prior positive beliefs related to earlier memories and beliefs related to the traumatic event is addressed. Positive emotions: Positive emotions are addressed as part of psychoeducation (numbing symptoms of PTSD, types of emotions) and as part of stuck points, especially in terms of appraisals of primary positive emotions (e.g., “I have no right to be feel happiness when someone has died” [survivor guilt]). Positive cognitions: The impact of the trauma on positive thoughts (safety, trust, self-esteem, power/control, and intimacy) embedded in prior positive memories is addressed. |

| Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR; Shapiro, 2017) | Positive memories, positive emotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: As an indicator of obstructed memory networks, clients may not be able to retrieve memories of experienced positive events. These obstructed memory networks are processed and integrated adaptively; consequently, recall of positive memories is enhanced. Positive memories are addressed in the context of teaching a breathing shift technique, wherein clients bring up a positive memory and associated affect, notice the location of the breathing in the body, and repeat the process with a less distressing memory. The breathing pattern with the positive memory is to be transferred to other situations to reduce distress. When obtaining client history, therapists obtain chronological information about and level of distress for the 10 most positive memories. Positive emotions: Positive emotions are addressed in reference to an alternative desirable imagined future (i.e., how the client would like to be feeling, acting, and believing in the future). Specifically, when the target of processing is a positive one, such as an alternative positive imagined future template, associated imagery/beliefs/affect become more vivid. Positive emotions are discussed as an outcome of successful EMDR, wherein the negative internal experiences become less vivid/valid and the positive internal experiences become more vivid/valid. Positive emotions are addressed as part of relaxation exercises such as the safe/calm place; clients bring about an image of a safe place associated with peace/safety and then focus on the image/emotions/pleasant sensations while performing a series of eye movements to enhance positive affect. Positive emotions are addressed in the context of the EMDR resource development and installation technique. Here, clients identify what quality they would like to have more of and how differently they would like to feel to engage in effective behaviors; identify the positive experience when they had this quality; describe the positive experience and elicit an image of the experience; focus on sensations of that experience; receive an eye movement series; and change approach in dealing with challenging situations in the future. Positive emotions are addressed in the context of teaching a breathing shift technique as described above. Positive cognitions: Positive cognitions are addressed in reference to an alternative desirable imagined future (as described above); an outcome of successful EMDR (as described above); and as part of the primary treatment process (assessment and installation phases). Clients are asked to identify a desired positive cognition, which helps to inform treatment direction/plan and to identify what alternative neural network is to be stimulated. |

| Present-Centered Therapy (PCT; Bernardy et al., 2003; Foa et al., 2010) | Positive emotions | Positive emotions: Lack of positive emotions is addressed in the context of psychoeducation about PTSD symptoms of avoidance/numbing. |

| Present-Centered Therapy (PCT; Ford et al., 2011) | Positive memories, positive emotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: Positive memories are addressed in the context of being able to shift focus from the past to the present when discussing detailed positive childhood memories. Further, when assessing problems faced by the client, the therapist may elicit activities that provided pleasure or sense of accomplishment to the client in the past versus the present. Positive emotions: Emotional numbing symptoms are discussed as stress reactions in the psychoeducation component. When identifying problems faced by clients, the therapist elicits activities that used to provide pleasure to the client in the past versus current. Positive cognitions: Positive cognition-related components are discussed in the context of homework and treatment goals (enhancing empowerment) and in the context of being a time-limited treatment (clients can be active partner in enhancing self-efficacy). |

| Written Exposure Therapy (Sloan & Marx, 2019) | NA | NA |

| Narrative Exposure Therapy (Schauer et al., 2011) | Positive memories, positive emotions, positive cognitions | Positive memories: Positive memories are addressed in the lifeline phase, wherein negative and positive events are identified in a chronological order. The therapist helps the client focus on facts, names, and so on rather than the emotional and sensational components of these memories. The purpose is to get an overview of the important life events, which aids in structuring sessions. Positive memories are also addressed in the narration phase, wherein clients practice processing emotional/cognitive/physiological content for a pleasant event (briefer than for traumatic events). Positive emotions: Positive emotions are addressed in the “narration phase;” clients practice processing emotional content for a pleasant event (briefer than traumatic events). Positive cognitions: Positive cognitions are addressed in the narration phase; clients practice processing cognitive content for a pleasant event (briefer than traumatic events). |

Note. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; the PCT manual used in the Rauch et al. (2015) study had an addendum that addressed an increase in positive memories as an outcome of successful treatment.

CBT TARGET.

Positive memories are addressed in three ways (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011). First, positive memories are discussed in the context of one of the FREEDOM skills of identifying triggers; the therapist states that the triggers for stressful reactions may not necessarily be negative events but could be positive events/changes. Second, positive memories are addressed as part of the Life Book exercise, wherein clients create a picture of their life by including information on important (including positive) events, individuals, and issues. Last, positive memories are discussed in the context of one of the FREEDOM skills of making a contribution; the therapist encourages the client to elicit a memory of what they did in a stressful situation and how they made a positive difference in that situation. Relatedly, clients also add this component to their Life Book.

CPT.

Positive memories related to prior positive experiences are referenced in two ways (Resick et al., 2008). One, for bereavement-related work, therapists may address positive memories of lost loved ones as triggered by holidays or personal days of celebration. Second, more generally, therapists address how positive beliefs regarding safety, trust, self-esteem, power/control, and intimacy embedded in prior positive memories have been impacted by the index trauma. Relatedly, therapists work on conflicts between these prior positive beliefs drawn from positive memories and the trauma-related beliefs.

EMDR.

Positive memories are addressed as an indicator of obstructed memory networks (thereby targeted in treatment) in the context of teaching a “Breathing Shift” coping skill (clients bring up a positive memory and associated affect, they notice where the breathing is in the body, and then do the same with a low-disturbance memory) and in obtaining client history (Shapiro, 2017).

BEPP.

Positive memories are discussed in the context of imaginal exposure that primarily targets trauma memories for emotional release and catharsis (Gersons et al., 2011). When clients are too tense despite relaxation exercises or the client is afraid of exposure to trauma memories, a focus on positive memories is considered helpful. Notably, BEPP primarily addresses sensations included in positive memories and focuses on recovering details of the positive memory (using mementos, letters, etc.) to facilitate catharsis of emotions.

PCT.

Positive memories are mentioned in the context of being able to shift the client’s focus from the past to the present when discussing traumatic memories or associated positive/negative childhood memories in detail (Ford et al., 2011). Positive memories are also discussed in the context of assessing problems faced by the client; the therapist elicits activities that provided pleasure or a sense of accomplishment to the client in the past versus the present (Ford et al., 2011).

NET.

Positive memories are addressed in two phases of this intervention (Schauer et al., 2011). One, during the lifeline phase, negative and positive memories are identified in chronological order. Such information provides an overview of the important life memories to structure therapy sessions. Second, positive memories are handled in the narration phase wherein clients practice processing the emotional content and recollect cognitive/physiological details of an identified pleasant memory.

IPT.

Positive memories are addressed primarily in the middle phases of treatment (Markowitz, 2017). The therapist elicits and discusses content from memories of affectively-charged incidents including any positive ones. The goal is to explore interpersonal functioning in these events to strengthen interpersonal skills.

Positive Emotions

Discussion of positive emotions. Overall, 69.23% of intervention protocols had an explicit discussion of positive emotions; they were CBT HOPE, CBT TARGET, CPT, EMDR, BEPP, PCT (both versions), NET, and IPT.

Goals of focusing on positive emotions.

CBT HOPE.

A lack of positive emotions is discussed in the context of emotional numbing (Johnson et al., 2004). Specifically, emotional numbing is addressed to examine its negative impact and to conduct its functional analyses; there is a focus on coping with emotional numbing symptoms.

CBT TARGET.

First, positive feelings are discussed in the context of goals of the treatment (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011). Specifically, the therapist indicates that using the FREEDOM skills effectively can result in positive emotions such as energized hopefulness. Second, positive emotions are discussed in the context of the FREEDOM skill of evaluating main (vs. reactive) thoughts occurring during an extreme stress reaction; positive emotions may be triggered by one’s interpretation of events (i.e., via thoughts) rather than what actually occurs (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011).

CPT.

Positive emotions are addressed in the content of psychoeducation about (1) the numbing symptoms of PTSD and (2) types of natural/universal and manufactured emotions arising from experienced events (e.g., joy from positive experiences; Resick et al., 2008). Further, positive emotions are addressed as a stuck point, especially in terms of appraisals of primary positive emotions (Resick et al., 2008).

EMDR.

Positive emotions are addressed (1) in reference to an alternative desirable imagined future (expansion of the installation phase wherein it is explored how the client would like to be feeling, acting, and believing in the future); (2) as an outcome of successful EMDR, wherein the negative affect becomes less vivid/valid and the positive affect becomes more vivid/valid; (3) as part of relaxation exercises (history-taking phase) such as the “safe/calm place;” (4) in the context of the resource development and installation technique (special protocol) which is an affect-regulation technique; and (5) as part of a “breathing shift” technique wherein clients bring up a positive memory and associated affect, notice where the breathing is in the body, and then do the same with a low-disturbance memory (Shapiro, 2017).

BEPP.

Positive emotions are discussed in the context of transference that may include identifying positive emotions and exploring their origin (Gersons et al., 2011).

PCT.

A lack of positive emotions is discussed in the context of psychoeducation about PTSD’s emotional numbing symptoms (Foa et al., 2010).

PCT.

Positive emotions are discussed in the context of psychoeducation wherein emotional numbing symptoms are discussed as stress reactions (Ford et al., 2011). Positive emotions are also discussed when identifying problems faced by clients; the therapist elicits activities that used to provide pleasure to the client in the past however do not do so currently (Ford et al., 2011).

NET.

Positive emotions are addressed in the narration phase, wherein if clients identify a particularly pleasant event, they practice processing its emotional content and recollect cognitive/physiological details (Schauer et al., 2011).

IPT.

Positive emotions are addressed in the context of emotional reactions to interpersonal situations linked to the trauma, specifically in the context of resolving grief in relation to a lost person (Markowitz, 2017).

Positive Cognitions

Discussion of positiave cognitions. Overall, 69.23% of intervention protocols had an explicit discussion of positive cognitions; they were BEPP, CBT, CBT HOPE, CBT TARGET, CPT, EMDR, PCT (Ford et al., 2011 Version), NET, and SIT.

Goals of focusing on positive cognitions.

BEPP.

Positive cognitions are addressed in the meaning/integration phase that aids clients in processing the trauma and learn from it (Gersons et al., 2011). One of the anticipated outcomes of this phase is the potential development of a new (likely realistic and positive) sense of self; elements include greater self -worth, realistic/adequate anticipation of the future, and/or stable sense of safety (referencing post-traumatic growth).

CBT.

The positive cognition-related component of positive self-talk is discussed as a coping skill for intrusion symptoms and nightmares characteristic of PTSD (Mueser et al., 2008). Positive self-statements are discussed in the context of coping with anger-provoking situations (cognitive restructuring for anger).

CBT HOPE.

The positive cognition-related component of positive affirmations is discussed as part of the empowerment tools used to re-think survivor thoughts and to self-soothe (Johnson et al., 2004). The positive cognition-related component of positive self-talk is discussed in the context of coping with trauma triggers (Johnson et al., 2004). The positive cognition-related component of positive coping statements is discussed in terms of grounding to reality (present-oriented techniques; Johnson et al., 2004).

CBT TARGET.

First, positive cognitions are addressed in relation to one treatment goal that is to help the client develop a strong and positive sense of identity (Ford, 2015; Ford et al., 2011). Second, the positive cognition-related component of positive self-image is addressed in psychoeducation when explaining how the brain and body are impacted by extreme stress. To elaborate, therapists educate clients that during normal stress times, the body and brain work together toward effective emotion regulation so that individuals can develop a realistic/positive self-image and build/maintain healthy relations. However, this system is in survival and alarm modes when experiencing extreme stress, which impacts one’s self-image. Third, positive cognition-related components are addressed in the FREEDOM skill of making a contribution; the therapist encourages the client to elicit a memory of their reactions and how they made a positive difference in stressful situations, enabling them to build a sense of true worth.

CPT.

Positive cognitions are primarily discussed in terms of addressing conflicts between prior positive beliefs and current trauma-related beliefs (Resick et al., 2008).

EMDR.

Positive cognitions are addressed (1) in reference to an alternative desirable imagined future (explained above for positive emotions); (2) as an outcome of successful EMDR, wherein the negative cognitions becomes less vivid/valid and the positive cognitions becomes more vivid/valid; and (3) as a part of the primary treatment process (assessment and installation phases). To elaborate on Point 3, during the assessment phase, clients are asked to identify a negative cognition associated with the target event and a desired positive cognition which helps to inform the treatment direction/plan and helps to identify the alternative neural network that is to be stimulated (Shapiro, 2017). During the installation phase, following processing of the trauma material, the positive cognition is linked with the previously upsetting information (memory network that holds the target material; Shapiro, 2017). Subsequent to the complete installation of the positive cognition with the target event, both are held in mind together to scan the body for any disturbing sensations (Shapiro, 2017).

PCT.

Positive cognition-related components are discussed in the context of (a) the goal of homework, which is to enhance client empowerment; (b) being a time-limited treatment, wherein the clients can be active partners in enhancing their self-efficacy; and (c) treatment goals that is to support ad build a sense of empowerment (Ford et al., 2011).

NET.

Positive cognitions are addressed in the narration phase, wherein if clients identify a particularly pleasant event, they practice processing its emotional content and recollect cognitive and physiological details (Schauer et al., 2011).

SIT.

Positive cognitions are addressed via positive self-talk and positive self-statements (guided self-dialogue). These are addressed as part of developing coping strategies tailored to four categories: preparing for stressor, confronting and handling a stressor, coping with feelings of being overwhelmed, and reinforcing self-statements (Foa et al., 1999, 2007).

Discussion

Research over the past two decades has demonstrated a growing interest in the role of positive internal experiences in psychology (Fredrickson, 2001; Gruber & Moskowitz, 2014). The relevance of these experiences to PTSD has been documented wherein individuals with PTSD symptoms have been found to exhibit deficits in positive memory processes (Contractor, Banducci, et al., 2019; Contractor, Greene, et al., 2020); difficulties experiencing, expressing, and/or regulating intense positive emotions (Weiss et al., 2018; Weiss, Nelson, et al., 2019); and reduced positive cognitions (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006; Janoff-Bulman, 1992). However, despite empirical evidence linking positive internal experiences to PTSD symptomatology, relatively little is known about the extent to which these experiences are addressed in PTSD interventions. The goal of the current review was to address this critical gap in the literature by examining the extent to which positive internal experiences are targeted and discussed in empirically validated PTSD interventions.

Positive Internal Experiences and PTSD Interventions

Results of the current review indicate that positive memories were addressed in just about half of the reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions. For some of these interventions, positive memories were considered integral to the primary proposed mechanism underlying PTSD. For instance, CPT describes traumatic events as shifting beliefs related to prior positive memories, whereas in EMDR, positive memories are indicative of obstructed memory networks. For other treatments, strategies addressing positive memories were considered as a precursor or a complement to targeting negative internal experiences (e.g., trauma memories). For example, in BEPP, a shift to focusing on positive memories is recommended when clients are tense despite learning and practicing relaxation exercises or afraid to address trauma memories. Similarly, in NET, clients practice processing the emotional content of a positive memory by recollecting its details in preparation for addressing negative internal experiences. In other treatments, positive memories were an indicator of treatment progress. For instance, in IPT, clients identify interpersonal functioning and skills successfully used in prior positive interpersonal experiences (i.e., they are asked to recollect positive memories specific to interpersonal events); this content is used to indicate and gauge progress in skill development and to improve coping. Last, PCT (Ford et al., 2011 Version) uniquely uses positive memories to identify client problems (i.e., by asking them to provide recollections of activities that brought them pleasure in the past vs. the present). This being said, other PTSD interventions can integrate positive memories into their primary therapeutic strategies, particularly when used as a practice and preparatory exercise to facilitate processing of trauma memories (e.g., PE) and when content from positive memories is explicitly used to aid cognitive restructuring of trauma beliefs (e.g., CPT and CBT; Contractor et al., 2018).

Positive emotions were one of the most addressed positive internal experiences in the reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions. Positive emotions are most frequently discussed in the context of providing psychoeducation on core PTSD symptoms and on reactions to stressful events. For example, in CBT HOPE, CPT, and PCT, treatment includes a description of a lack of positive emotions (i.e., emotional numbing) as a PTSD symptom. In CPT and IPT, a lack of positive emotions is described as one common emotional reaction to stressful events (e.g., when experiencing grief). Other examples of how positive emotions are addressed include (a) when interpreting stressful events in CBT TARGET, (b) during transference in BEPP, and (c) to prepare clients for targeting negative internal experiences (i.e., practice processing the emotional content of a positive memory) in NET. The treatment that most comprehensively addresses positive emotions is EMDR; positive emotions are addressed during several treatment phases (e.g., installation phase to identify a desirable imagined future, history-taking phase to elicit relaxation) and techniques (e.g., resource development and installation, breathing shift). Again, other interventions have the potential to explicitly focus on and integrate (coping with) positive emotions: (1) guided self-talk in SIT could be broadened to include positive emotions; (2) cognitive restructuring in CBT could address dysregulation of positive emotions (particularly because positive emotions could be followed by negative thoughts that need restructuring; Weiss, Darosh, et al., 2019; Weiss, et al., 2015); (3) IPT could address positive emotions as a part of psychoeducation on PTSD symptoms as well as in the context of affective arousal, wherein clients are allowed to experience powerful emotions as less threatening/dangerous; and (4) CPT could extend the therapeutic technique of preventing emotional avoidance to positive affect, whose secondary appraisal may lead to distressing thoughts and manufactured emotions (Frewen, Dean, & Lanius, 2012; Frewen, Dozois, & Lanius, 2012).

Last, positive cognitions were also one of the most addressed positive internal experiences in the reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions. Almost all of these treatments addressed positive cognitions in the context of coping with negative internal experiences, including using positive self-talk, positive self-statements, positive affirmations, and self-soothing (CBT, CBT HOPE, SIT). In NET, positive cognitions were also addressed as a way to prepare clients for targeting negative internal experiences (i.e., practicing processing the cognitive content of a positive memory). In BEPP and CBT TARGET, positive cognitions were targeted to enhance sense of self (e.g., identity, worth). Differently, in BEPP and in PCT (Ford et al., 2011 Version), positive cognitions were addressed in the context of being an indicator of an anticipated outcome of therapy (i.e., development of a new self-concept, enhanced sense of empowerment). Finally, similar to positive emotions, the treatment that most comprehensively addressed positive cognitions was EMDR; positive cognitions are addressed in several treatment phases (e.g., installation phase to identify a desirable imagined future). As with other positive internal experiences, and perhaps with more ease, positive cognitions could be integrated into other interventions. For example, embedded positive thoughts in positive memories could be more explicitly and directly used to aid accommodation in CPT.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

This critical review has important implications to inform future research. First, many of the reviewed empirically validated PTSD treatments discussed memories, emotions, and cognitions without reference to positive or negative valence. As such, there may be substantial variability among clinicians in the extent to which positive internal experiences are implemented in PTSD interventions. For clinicians who are familiar with the literature linking positive internal experiences to PTSD, there may be more of an explicit focus on positive memories, emotions, and/or cognitions throughout treatment. For other clinicians, such a focus may only occur when the client’s presenting problems are directly tied to positive internal experiences (e.g., emotional numbing is central to the presentation). Still, other clinicians may never assess for or address positive internal experiences in PTSD treatment; perhaps, clinicians conceptually link trauma with negative internal experiences and do not consider the influence of processing positive internal experiences on distress (Lyubomirsky et al., 2006). Recent research indicates that trauma-exposed clients (Caldas et al., 2020) and trauma clinicians (Contractor, Caldas, et al., 2019) are willing and interested in discussing more positive internal experiences (positive memories in particular) during treatment, which provides an impetus for future research to explore ways in which positive internal experiences are actually addressed in practice (e.g., by reviewing audio transcripts of PTSD sessions provided by clinicians in the community).

Second, positive internal experiences were not central to any of the reviewed empirically validated PTSD interventions. Positive psychotherapy—which reduces negative internal experiences by directly targeting positive internal experiences—has been shown to be efficacious for a wide range of mental health conditions; (e.g., depression; Seligman et al., 2006) and clinically-relevant behaviors (e.g., smoking; Kahler et al., 2014). Further, memory-based interventions, in particular those that enhance recall of memories irrespective of their valence, have been found to relate to better mental health including lower PTSD severity (Korrelboom et al., 2012; Moradi et al., 2008; Neshat-Doost et al., 2013). Research in this area suggests the potential utility of developing PTSD interventions (as standalone or augments) with a primary and unique focus on addressing positive internal experiences to reduce PTSD symptoms (Callahan et al., 2019; Contractor et al., 2018). Future research in this area is warranted.

Third, the extent to which an enhancement of positive internal experiences is an outcome of PTSD intervention or relates to the efficacy of PTSD interventions (e.g., positive outcomes posttreatment) is vastly unknown and was not amenable to this study’s review. Relatedly, the mechanisms through which positive internal experiences may enhance the efficacy of PTSD treatments require a nuanced empirical examination via a component analyses of interventions targeting positive internal experiences. Indeed, strategies addressing positive internal experiences may relate to positive outcomes for PTSD treatment via several mechanisms. For instance, positive memories may replace trauma memories as the reference point for an individual’s self-concept serving as the primary lens to interpret life situations (Berntsen, 2001; Bohanek et al., 2005; Pillemer, 1998), and/or positive emotions may trigger positive cognitions and behaviors (Fredrickson, 2001; Rusting & DeHart, 2000). Research that improves our understanding of the influence of positive internal experiences on PTSD treatment outcomes will be useful in modifying/individualizing PTSD treatments and in developing novel PTSD treatments to improve treatment outcomes (including retention), given that current PTSD interventions do not work effectively for every client (Resick et al., 2002).

Last, EMDR seems to be the treatment protocol, followed by CBT TARGET, NET, BEPP, and CPT, with the most comprehensive focus on positive internal experiences compared to other reviewed PTSD interventions. Such protocols may be a good starting point for clinicians who wish to target positive internal experiences consistent with client’s presenting concerns/goals, to improve therapeutic rapport, to help clients develop a repertoire of coping skills during initial therapy sessions, to socialize clients into therapy, and/or to provide clients a practice platform to address (vs. avoid) negative internal experiences. Relatedly, clinicians have a wider spread of interventions to choose from if they wish to therapeutically target positive emotions/cognitions versus positive memories, given that positive emotions/cognitions are most frequently addressed by the reviewed treatment protocols. A caveat in this regard is that positive emotions may not always be accepted/tolerated and associated with positive outcomes among individuals with severe PTSD (Weiss, Darosh, et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2018; Weiss, Nelson, et al., 2019). Thus, research needs to examine the need and impact of targeting regulation of positive emotions as a part of PTSD interventions.

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the findings of this review. First, we excluded PTSD interventions based on predetermined criteria (e.g., our review cannot speak to PTSD interventions developed for children and adolescents), and we did not examine all versions of the reviewed PTSD interventions (e.g., CPT with and without a trauma narrative writing component; interventions tailored to civilians vs. military personnel) to make this review feasible in scope and to retain meaning of obtained results. Additionally, a consequence of our systematic procedure in selecting PTSD interventions for the current review was a possible exclusion of interventions from diverse theoretical orientations (e.g., psychodynamic theory), particularly those that do not lend themselves to manualized treatment formats.

Second, several authors who were contacted for intervention manuals either did not respond or responded without providing the intervention manual or the source/reference for the intervention manual. For instance, 57.14% (n = 8), 20.00% (n = 1), and 66.67% (n = 2) of authors contacted for CBT, PCT, and CT, respectively, did not respond and 7.14% (n = 1), 20.00% (n = 1), and 33.33% (n = 1) of authors contacted for CBT, PCT, and CT, respectively, responded either without intervention manuals or without references for intervention manuals. Thus, the current review cannot speak to all PTSD interventions such as CT, whose review would have been vital because of its emphasis on enhancing positive experiences (reclaiming your life assignment) and a positive sense of self (Ehlers & Wild, 2015). Also, this review does not capture the breadth of PTSD interventions varying in frequency of use as well as in representativeness of what is used in clinical practice and research (e.g., review of different versions of CBT manuals would have expanded applicability of study findings) and this review simultaneously includes first-line therapies and active controls (e.g., PCT is quite often used as an active control treatment; Surís et al., 2013).

Third, our review focused on the content of empirically validated PTSD intervention manuals versus the RCTs that demonstrated their efficacy. Thus, while many of these intervention manuals have been shown to have empirical support in a wide range of populations (e.g., with regard to age, gender, and race; Blain et al., 2010; Clapp & Beck, 2012; Lester et al., 2010), the generalizability of our findings to specific populations is unknown. There is some evidence that positive internal experiences vary among cultural groups. For example, somatic symptoms may be more common among Latin Americans (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, 2011), and some positive emotions such as pride may be more regulated among cultures that adhere to collectivistic principles (Parker et al., 2012). Relatedly, all reviewed intervention manuals were in the English language and from Western countries such as United States (n = 11), Germany (n = 1), and the Netherlands (n = 1), and we did not capture cultural adaptations of these reviewed manuals in the search process. Thereby, we cannot extrapolate applicability of study findings to diverse cultures. Future research examining the extent/manner of addressing positive internal experiences in cultural adaptations of PTSD interventions is warranted.

Fourth, we did not assess for all types of internal emotional experiences such as physical sensations. Physiological responses (e.g., heart rate variability) to positively valenced cues have shown to be heightened among individuals with PTSD symptoms (Litz et al., 2000). Further, evidence indicates that augmenting PTSD treatment with interoceptive exposure results in pre- to posttreatment reductions in fear of physiological sensations (e.g., heart rate, blushing; Wald & Taylor, 2007), which may stem from positive emotional experiences. Thus, future investigations in this area would benefit from the examination of physical sensations tied to positive stimuli. Last, our review was restricted to identifying whether and how intervention manuals explicitly and directly addressed positive internal experiences. Hence, our findings may not reflect and adequately address variations in therapist interpretations and modifications of manual content in clinical practice and research. Relatedly, therapists may address certain positive internal experiences that are not explicit in the intervention manual but related to other content/goals of the intervention.

Despite these study limitations, the current critical review advances literature by summarizing the extent to which positive internal experiences are addressed in empirically validated treatments for PTSD. Specifically, our findings indicate that positive internal experiences (particularly positive memories) are infrequently addressed in empirically validated treatments for PTSD. Further, when positive internal experiences are addressed, they are often not central and rather adjunctive to the targets of negative internal experiences.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

Positive emotions and cognitions are the most targeted positive internal experiences among reviewed protocols; clinicians need to consider imparting skills to effectively address positive emotions and cognitions among trauma-exposed clients with PTSD symptoms.

EMDR has the most comprehensive focus on positive internal experiences among reviewed protocols.

Positive internal experiences, although frequently addressed in empirically validated treatments for PTSD, are not central but rather are adjunctive to the targets of negative internal experiences.

Strategies addressing positive internal experiences may relate to positive treatment outcomes for PTSD via several mechanisms (e.g., countering trauma-related beliefs and replacing the trauma memory as the primary reference to influence one’s identity).

Funding is needed to support research on the influence of positive internal experiences on PTSD development, maintenance, and treatment.

Policy makers at all levels (e.g., community, national, international) may benefit from an awareness of the potential utility of targeting positive internal experiences in PTSD treatment.

All relevant stakeholders would benefit from routinely screening for disruptions in positive internal experiences among individuals who present for trauma/PTSD treatment to inform optimal treatment choice.

Component analyses of interventions targeting positive internal experiences are needed to examine their potentially unique and active role in treatment effectiveness

Review of different versions (e.g., cultural adaptations, teletherapy, group treatment) of empirically validated PTSD interventions and review on other types of internal experiences (e.g., physical sensations) is needed to advance the understanding of positive internal experiences in PTSD interventions.

Empirical examination of the potential utility of developing PTSD interventions to primarily focus on reducing PTSD symptoms through an improvement in positive internal experiences is needed.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Nazaret Suazo and Julissa Godin for their assistance with this project.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research described here was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA039327) awarded to Dr. Weiss.

Author Biographies

Ateka A. Contractor, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology, University of North Texas. Her program of research examines heterogeneity/diversity in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, heterogeneity (pattern and types) of traumatic experiences, transdiagnostic constructs/mechanisms driving PTSD’s relationship with depression and reckless behaviors (including positive memory processes and emotional dysregulation), and the intersection between cultural factors and PTSD symptoms.

Nicole H. Weiss, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Rhode Island and the director of the Study of Trauma, Risk-taking, Emotions, and Stress Symptoms (STRESS) Lab. Her clinical and research interests focus on the role of emotion dysregulation in PTSD and co-occurring risky, self-destructive, and health-compromising behaviors, most notably substance use and HIV/sexual risk. She is also interested in the influence of cultural and contextual factors, including race/ethnicity and gender, on the interrelations among PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and risky behaviors.

Shannon R. Forkus, MA, is a second-year PhD student in the Clinical Psychology program at the University of Rhode Island. Her research focuses on examining cognitive and affective factors that influence the relations between trauma, PTSD, and risky behaviors.

Fallon Keegan, BA, is a second-year PhD student in the Clinical Psychology program at the University of North Texas. Her research interests include examination of risk factors for developing PTSD and processes in treating PTSD and comorbid depressive/anxiety disorders.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Author. [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle RL, Melrose AJ, Stein MB, & Paulus MP (2012). Executive function and PTSD: Disengaging from trauma. Neuropharmacology, 62, 686–694. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardy N, Davis N, Howard J, Key F, Lambert J, & Shea MT (2003). Present-centered therapy (PCT) manual [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D (2001). Involuntary memories of emotional events: Do memories of traumas and extremely happy events differ? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, S135–S158. 10.1002/acp.838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, & Rubin DC (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 219–231. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain LM, Galovski TE, & Robinson T (2010). Gender differences in recovery from posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 463–474. 10.1016/j.avb.2010.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney PH (1986). Affect and memory: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 229–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.99.2.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Fivush R, & Walker E (2005). Memories of positive and negative emotional events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19, 51–66. 10.1002/acp.1064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas SV, Jin L, Dolan M, Dranger P, & Contractor AA (2020). An exploratory examination of client perspectives on a positive memory technique for PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 208(3), 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan JL, Maxwell K, & Janis BM (2019). The role of overgeneral memories in PTSD and implications for treatment. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 29, 32–41. 10.1037/int0000116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, & Beck JG (2012). Treatment of PTSD in older adults: Do cognitive-behavioral interventions remain viable? Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19, 126–135. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Banducci AN, Dolan M, Keegan F, & Weiss NH (2019). Relation of positive memory recall count and accessibility with posttrauma mental health. Memory, 27, 1130–1143. 10.1080/09658211.2019.1628994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Banducci AN, Jin L, Keegan F, & Weiss NH (2020). Effects of processing positive memories on posttrauma mental health: A preliminary study in a non-clinical student sample. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 66(101516). 10.1016/j.jbtep.2019.101516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Brown LA, Caldas S, Banducci AN, Taylor DJ, Armour C, & Shea MT (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and positive memories: Clinical considerations. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58, 22–32. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Caldas SV, Dolan M, Banducci AN, & Jin L (2019). Exploratory examination of clinician perspectives on positive memories and posttraumatic stress disorder interventions. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 10.1002/capr.12267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Greene T, Dolan M, Weiss NH, & Armour C (2020). Relation between PTSD clusters and positive memory characteristics: A network perspective. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 69. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, Wines C, Sonis J, Middleton JC, Feltner C, Brownley KA, Olmsted KR, Greenblatt A, Weil A, & Gaynes BN (2016). Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychological Review, 43, 128–141. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, & Clark DM (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 38, 319–324. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, & Wild J (2015). Cognitive therapy for PTSD: Updating memories and meanings of trauma. In Schnyder U & Cloitre M (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders: A practical guide for clinicians (pp. 161–187). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fani N, Tone EB, Phifer J, Norrholm SD, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Kamkwalala A, & Jovanovic T (2012). Attention bias toward threat is associated with exaggerated fear expression and impaired extinction in PTSD. Psychological Medicine, 42, 533–543. 10.1017/S0033291711001565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Bernardy N, Davis N, Howard J, Key F, Lambert J, & Shea MT (2010). Present-centered therapy manual: A PCT manual modified for use in the STRONG STAR multidisciplinary PTSD research consortium study [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hearst DE, & Dancu CV (1999). Stress innoculation training and prolonged exposure (SIT/PE) manual [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, & Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences—Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Kozak MJ (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20–35. 10.1037//0033-2909.99.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD (2015). An affective cognitive neuroscience-based approach to PTSD psychotherapy: The TARGET model. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 69–91. 10.1891/0889-8391.29.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Steinberg KL, & Zhang W (2011). A randomized clinical trial comparing affect regulation and social problem-solving psychotherapies for mothers with victimization-related PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 42, 560–578. S0005-7894(11)00048-7[pii] 10.1016/j.beth.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1). 10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.31a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Dean JA, & Lanius RA (2012). Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: Development of the Hedonic Deficit and Interference Scale. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(3). 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.8585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Dozois DJ, & Lanius RA (2012). Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: Psychometric and neuroimaging perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3. 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.8587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia HA, Kelley LP, Rentz TO, & Lee S (2011). Pretreatment predictors of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Psychological Services, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gersons BPR, Meewisse ML, Nijdam MJ, & Olff M (2011). Brief eclectic psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, & Moskowitz JT (2014). Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides. Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Bryant RA, & Dang ST (1998). Autobiographical memory in acute stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 500–506. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree EA, Foa EB, Dorfan NM, Street GP, Kowalski J, & Tu X (2003). Do patients drop out prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 555–562. 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004078.93012.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, & Lewis-Fernández R (2011). The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 783–801. 10.1002/da.20753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R (1992). Shattered assumptions: Toward a new psychology of trauma. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, & DeLambo K (2004). HOPE treatment manual [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Day A, Clerkin EM, Parks A, Leventhal AM, & Brown RA (2014). Positive psychotherapy for smoking cessation: Treatment development, feasibility, and preliminary results. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 19–29. 10.1080/17439760.2013.826716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korrelboom K, Maarsingh M, & Huijbrechts I (2012). Competitive memory training (COMET) for treating low self-esteem in patients with depressive disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 102–110. 10.1002/da.20921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester K, Resick PA, Young-Xu Y, & Artz C (2010). Impact of race on early treatment termination and outcomes in posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 480–489. 10.1037/a0019551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Kaloupek D, & Weathers F (2000). Emotional processing in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 26–39. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, & Diener E (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Sousa L, & Dickerhoof R (2006). The costs and benefits of writing, talking, and thinking about life’s triumphs and defeats. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 692–708. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz C (2017). Interpersonal psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Macklin ML, & Pitman RK (1995). Autobiographical memory disturbance in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33, 619–630. 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00007-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megías JL, Ryan E, Vaquero JM, & Frese B (2007). Comparisons of traumatic and positive memories in people with and without PTSD profile. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 117–130. 10.1002/acp.1282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi AR, Herlihy J, Yasseri G, Shahraray M, Turner S, & Dalgleish T (2008). Specificity of episodic and semantic aspects of autobiographical memory in relation to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Acta Psychologica, 127, 645–653. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi AR, Moshirpanahi S, Parhon H, Mirzaei J, Dalgleish T, & Jobson L (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of memory specificity training in improving symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 56, 68–74. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Jankowski MK, Hamblen J, Rosenberg SD, Salyers MP, Bolton E, & Gottlieb JD (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in people with severe mental illness [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Neshat-Doost HT, Dalgleish T, Yule W, Kalantari M, Ahmadi SJ, Dyregrov A, & Jobson L (2013). Enhancing autobiographical memory specificity through cognitive training: An intervention for depression translated from basic science. Clinical Psychological Science, 1, 84–92. 10.1177/2167702612454613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F, Schauer M, Klaschik C, Karunakara U, & Elbert T (2004). A comparison of narrative exposure therapy, supportive counseling, and psychoeducation for treating posttraumatic stress disorder in an African refugee settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti M, Gooding PA, & Tarrier N (2012). An empirical investigation of the effectiveness of the broad-minded affective coping procedure (BMAC) to boost mood among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 589–595. 10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AE, Halberstadt AG, Dunsmore JC, Townley G, Bryant A, Thompson JA, & Beale KS (2012). “Emotions are a window into one’s heart”: A qualitative analysis of parental beliefs about children’s emotions across three ethnic groups. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 77, 1–136. 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2012.00676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer DB (1998). Momentous events, vivid memories. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quoidbach J, Mikolajczak M, & Gross JJ (2015). Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 655–693. 10.1037/a0038648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SA, King AP, Abelson J, Tuerk PW, Smith E, Rothbaum BO, Clifton E, Defever A, & Liberzon I (2015). Biological and symptom changes in posttraumatic stress disorder treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 32, 204–212. 10.1002/da.22331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2008). Cognitive processing therapy: Veteran/military version. Department of Veterans Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, & Feuer CA (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 867–879. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, & Schnicke M (1993). Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment manual (Vol. 4). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL, & DeHart T (2000). Retrieving positive memories to regulate negative mood: Consequences for mood-congruent memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 737–752. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL, & Larsen RJ (1998). Personality and cognitive processing of affective information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 200–213. 10.1177/0146167298242008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer M, Neuner F, & Elbert T (2011). Narrative exposure therapy: A short term treatment for traumatic stress disorders (2nd ed.). Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP (2017). Focusing on trauma-focused psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 56–60. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, & Marx BP (2009). Post-traumatic stress disorder and quality of life: Extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 727–735. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Rashid T, & Parks AC (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 61, 774–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, & Marx BP (2019). Written exposure therapy for PTSD: A brief treatment approach for mental health professionals. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Dockray S, & Wardle J (2009). Positive affect and psychobiological processes relevant to health. Journal of Personality, 77, 1147–1176. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00599.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surís A, Link-Malcolm J, Chard K, Ahn C, & North C (2013). A randomized clinical trial of cognitive processing therapy for veterans with PTSD related to military sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 28–37. 10.1002/jts.21765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland K, & Bryant RA (2005). Self-defining memories in post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 591–598. 10.1348/014466505X64081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group. (2017). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. VA Office of Quality and Performance. [Google Scholar]

- Wald J, & Taylor S (2007). Efficacy of interoceptive exposure therapy combined with trauma-related exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 1050–1060. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LE, Sprang KR, & Rothbaum B (2018). A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 258. 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Contractor AA, Forkus SR, Goncharenko S, & Raudales AM (2020). Positive emotion dysregulation among community individuals: The role of traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 10.1002/jts.22497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]