Abstract

A PCR assay, using three primer pairs, was developed for the detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum, parvo biovar, mba types 1, 3, and 6, in cultured clinical specimens. The primer pairs were designed by using the polymorphic base positions within a 310- to 311-bp fragment of the 5′ end and upstream control region of the mba gene. The specificity of the assay was confirmed with reference serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14 and by the amplified-fragment sizes (81 bp for mba 1, 262 bp for mba 3, and 193 bp for mba 6). A more sensitive nested PCR was also developed. This involved a first-step PCR, using the primers UMS-125 and UMA226, followed by the nested mba-type PCR described above. This nested PCR enabled the detection and typing of small numbers of U. urealyticum cells, including mixtures, directly in original clinical specimens. By using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR with seven arbitrary primers, we were also able to differentiate the two biovars of U. urealyticum and to identify 13 RAPD-PCR subtypes. By applying these subtyping techniques to clinical samples collected from pregnant women, we established that (i) U. urealyticum is often a persistent colonizer of the lower genital tract from early midtrimester until the third trimester of pregnancy, (ii) mba type 6 was isolated significantly more often (P = 0.048) from women who delivered preterm than from women who delivered at term, (iii) no particular ureaplasma subtype(s) was associated with placental infections and/or adverse pregnancy outcomes, and (iv) the ureaplasma subtypes most frequently isolated from women were the same subtypes most often isolated from infected placentas.

Ureaplasma urealyticum is a prevalent (40 to 80%) colonizer of the lower genital tract of pregnant women (5, 16) and is capable of causing serious infection in pregnant women and neonates. In pregnant women, U. urealyticum is a significant cause (often the sole isolate) of chorioamnionitis (13, 16, 19, 20, 26), frequently with a sequela of adverse pregnancy outcome. U. urealyticum may be acquired by neonates either in utero (27) or by vertical transmission at birth (1, 12, 32) and can cause pneumonia (27), pulmonary hypertension (37), chronic lung disease (4), and meningitis (10, 38) of the newborn. While up to 80% of women may be colonized with U. urealyticum, only a small proportion of these women develop chorioamnionitis. It is unknown why some women have adverse pregnancy outcomes, but it has been suggested that these may be due to either infections ascending from the lower genital tract (15), colonizers present in the endometrium at the time of embryo implantation (5), maternal risk factors, or the individual pathogenicities of ureaplasma isolates (5).

Of the various techniques used to subtype U. urealyticum, serotyping has been the most widely used method. Of the 14 serovars of U. urealyticum (30), serovar 3 is most frequently isolated from women (9, 22, 24). Some studies (22, 28, 34) have shown that serovars 4 and 8 are more frequently associated with infections, while other workers have shown that there is no particularly invasive U. urealyticum serovar(s) (40). The 14 serovars can be grouped into two biovars (8, 14, 29). The parvo biovar contains serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14, while the remaining 10 serovars belong to the T960 biovar. The two U. urealyticum biovars have also been distinguished by PCR of the MB (for multiple-banded) antigen gene (mba) (35), PCR of the 16S rRNA gene (31), and arbitrarily primed PCR (11, 18). Studies using serotyping (9, 22) and biotyping (by PCR) (1) to type clinical U. urealyticum isolates from pregnant women have demonstrated that parvo biovar ureaplasmas (64 to 95% of isolates) are isolated more frequently than are T960 biovar ureaplasmas (20 to 42%), regardless of the pregnancy outcome (i.e., normal delivery or adverse pregnancy outcome). However, Abele-Horn et al. (1) further showed that the T960 biovar was isolated significantly more often from women with miscarriages (42%) and pelvic inflammatory disease (57%) than from pregnant women who were admitted for delivery (20%).

Recently we have described a subtyping method for U. urealyticum based on polymorphisms within the sequence of the 5′ end and the upstream control region of the mba gene (17). By direct sequencing of the mba gene fragment, we defined five mba types (mba 1, 3, and 6 [parvo biovar] and mba 8 and X [T960 biovar]) and nine mba subtypes (mba 1a, 1b, 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d, 3e, 6a, and 6b, all of the parvo biovar) of U. urealyticum. The major objectives of the present study were to develop both a PCR assay for the direct detection of mba types in clinical specimens and an optimized random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR protocol for subtyping ureaplasma isolates. These two molecular subtyping methods were then used to test clinical isolates (collected during a previous prospective study) in order to establish the prevalence of the mba and RAPD-PCR types within a subset of this population and to determine if any of these types are of clinical relevance in invasive genital tract infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

A prospective clinical study was previously conducted at the public antenatal clinic of the Toowoomba Base Hospital, Queensland, Australia, to investigate U. urealyticum colonization rates in an Australian population and to determine whether either vaginal or endocervical ureaplasma colonization was associated with adverse pregnancy outcome (16). Briefly, the 162 women enrolled in this study were evaluated for lower genital tract colonization by culture at their first antenatal visit (8 to 25 weeks of gestation), and 120 women were retested at 28 weeks of gestation. Placentas from 92 of these women were also cultured. U. urealyticum was isolated from 57% of the women at their first antenatal visit, from 53% of them at 28 weeks of gestation, and from 17% of the placentas. U. urealyticum culture-positive clinical samples from this prospective study (33 samples in total from 17 women) were tested in the present study. The selection of clinical samples (22 endocervical samples, 4 vaginal samples, and 7 placental samples) was based on the pregnancy outcome and/or histological examination of the placenta. We selected 14 samples from seven women who delivered preterm and 18 samples from nine women who delivered at term, and there was one other sample whose gestation details were unknown.

Reference serovars.

The reference strains of U. urealyticum (serovars 1, 3, 6, 14, and 8) used in this study were provided by G. L. Gilbert (University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia), with the kind permission of H. L. Watson (University of Alabama, Birmingham). Serovars 1, 3, 6, and 8 were originally obtained from E. A. Freundt (Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark), and serovar 14 was originally obtained from J. A. Robertson (Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada).

Culture of U. urealyticum.

All specimens were collected and cultured as previously described (16). Briefly, vaginal and endocervical samples were collected during a speculum examination. The chorionic surface of the placenta was sterilized with burning alcohol, and, by means of aseptic technique, a block of villous tissue was excised. These samples and the reference serovars were inoculated into U9B or 10B liquid broth (33, 34) and onto A8 agar medium (modified; Becton Dickinson, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia). Four serial 10-fold dilutions of the liquid broth were made, and growth was detected by an alkaline shift. The A8 plates were incubated at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% N2 and 5% CO2, and colonies were detected microscopically.

DNA preparation.

Ureaplasma DNA was prepared by one of two methods (2). In the first method, stored clinical samples (U9B broth) of U. urealyticum (cultures or original clinical specimens) were thawed, and 250 μl of each sample was centrifuged at 15,900 × g (Microfuge E; Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.) for 20 min at 4°C. Each pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of solution A (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2) and 50 μl of solution B (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, 1% Triton X-100) with 120 μg of proteinase K per ml; it was incubated for 1 h at 60°C, followed by 10 min at 94°C, and then cooled. Five microliters of each prepared sample was used immediately for mba gene PCR or stored at −20°C until PCR analysis. If larger quantities of DNA were required, the second method was used. In this procedure, stored clinical samples (original specimens or cultures) and cultures of reference serovars 1, 3, 6, 14, and 8 were inoculated individually into 25 ml of 10B broth and incubated at 37°C until an alkaline color change was observed. Each broth culture was then centrifuged at 24,000 × g (Beckman model J2-21M/E) for 1 h. The pellets were each washed in 2 ml of cold Tris-EDTA buffer and recentrifuged for 15 min at 15,900 × g (Beckman Microfuge E) at 4°C. Each pellet was resuspended in equal volumes (250 μl) of solutions A and B with 120 μg of proteinase K per ml and then incubated for 1 h at 60°C. The samples were cooled, and the DNA was extracted (36) with equal volumes of (i) phenol, (ii) phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol), and (iii) chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol) and then precipitated from the aqueous phase with 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2 volumes of ethanol. Each DNA pellet was resuspended in 25 μl of water.

Detection of types mba 1, mba 3, and mba 6 in cultures by PCR.

By exploiting the polymorphic base positions within the mba fragment (17), we designed three sets of primers which selectively amplify the mba types (1, 3, and 6): UMS-83 (5′-GTAGAAATTATGTAAGATTG-3′) and UMA-41 (5′-AAAATATGTCATTTTATTGTC-3′) for mba 1, UMS-81 (5′-AGAAATTATGTAAGATTACC-3′) and UMA144 (5′-CGCATAAAAACTTTTACCG-3′) (which will not amplify fragments from serovar 14 [mba type 3e]) for mba 3, and UMS-53 (5′-GTGTTCATATTTTTTACTAG-3′) and UMA122 (5′-GTTGATTTAACAAATTGGC-3′) for mba 6. The primers were designated UMS or UMA to indicate whether they were derived from the sense (S) or antisense (A) ureaplasma mba gene. The number refers to the location on the mba gene map (for serovar 3) (39) and corresponds to the 3′-most base of the primer.

One-step mba PCR conditions.

Separate PCRs were performed for each primer pair. The reaction mixture (50 μl) contained 1 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 500 mM KCl, pH 8.3; Boehringer), 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Boehringer), water, 20 pmol of each primer, and DNA template (5 to 10 μl of prepared sample or 1 μl of extracted DNA). The three PCRs were individually optimized, and the reaction parameters for each primer pair were critical. The DNA thermal cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) was programmed for 1 cycle of denaturation at 94°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles (mba 3 and mba 6) or 40 cycles (mba 1) consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 45 s at 56°C (mba 1) or 55°C (mba 3 and mba 6), and extension at 72°C for 45 s. This was followed by a final cycle of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 2.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Reference serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14 were used as controls.

Nested PCR for the detection of types mba 1, mba 3, and mba 6 in original clinical specimens.

While one-step mba PCR detected the mba types in cultures of clinical specimens, it was not sufficiently sensitive to detect low levels of U. urealyticum in the original clinical specimens. We therefore developed a nested PCR which also targeted the mba gene to test for U. urealyticum types in the original clinical specimens. We used the outer-primer pair UM-1 (UMS-125 and UMA226) to amplify a 403- or 404-bp mba fragment from parvo biovar ureaplasmas as previously described (17) followed by three separate reactions using the inner-primer pairs for mba 1 (UMS-83 and UMA-41), mba 3 (UMS-81 and UMA144), and mba 6 (UMS-53 and UMA122). The reference serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14 were also tested by nested mba PCR as controls. For the outer-primer reaction, we used 5 μl of the prepared clinical sample (2) in a 50-μl reaction mixture and previously described reaction conditions (17). For the nested mba PCR, we used 1 μl of the outer-primer reaction mixture and the mba reaction conditions. Again, these reactions were individually optimized, and it was found to be necessary to increase the stringency of these reactions by using annealing temperatures of 57°C (mba 1 and 6) and 58°C (mba 3). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 2.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

RAPD-PCR profiling of U. urealyticum. (i) Primers.

Twenty 10-base primers (FPK-2; Bresatec, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia) were screened, and from these, 14 primers (FPK 2-01 [5′ AAGCTGCGAG 3′], 2-03 [5′ CTGGCGTGAC 3′], 2-06 [5′ TTCGAGCCAG 3′], 2-07 [5′ GAACGGACTC 3′], 2-08 [5′ GTCCCGACGA 3′], 2-09 [5′ TGTCATCCCC 3′], 2-10 [GGTGATCAGG 3′], 2-11 [5′ CCGAATTCCC 3′], 2-12 [5′ GGCTGCAGAA 3′], 2-13 [5′ CTGACCAGCC 3′], 2-17 [5′ CACAGGCGGA 3′], 2-18 [5′ TGACCCGCCT 3′], 2-19 [5′ GGACGGCGTT 3′], and 2-20 [5′ TGGCGCAGTG 3′]) were selected for use in RAPD-PCR profiling of 22 clinical isolates.

(ii) RAPD-PCR.

RAPD-PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 1 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Scoresby, Victoria, Australia), 10× PCR buffer (0.67 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.098 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Tween 20), 125 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Boehringer), 40 pmol of arbitrary primer, 5.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 μl of extracted DNA template. The optimum DNA concentration for this RAPD-PCR was found to be in the range of 0.1 to 1.56 ng/μl; however, most DNA samples were tested at a concentration of 0.35 ng/μl. The reaction mixture was overlaid with 1 drop of paraffin oil. To avoid contamination, preparation of the PCR master mix (for mba PCR and RAPD-PCR) and addition of DNA were conducted in separate rooms and a negative control was always included. Amplification was performed in a Perkin-Elmer thermal cycler, with a first cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles consisting of denaturation for 1 min at 91°C, annealing for 1 min at 38°C, and extension for 2 min at 72°C. The RAPD-PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels at 100 V for 75 min. The gels were poststained with ethidium bromide for 15 min, destained with 1 mM MgSO4 for 20 min, visualized with UV light, and digitized by using Grab-IT (Ultraviolet Products LTD, Cambridge, England, United Kingdom). The banding patterns of the amplification products were compared visually, and polymorphic bands were scored as either present or absent. The clinical isolates were classified into RAPD subtypes on the basis of these polymorphisms.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed by using a binomial test for proportions on SPSS version 7.5 to determine if there were statistically significant differences in the prevalence of U. urealyticum mba types between women who delivered preterm and those who delivered at term.

RESULTS

mba subtypes of U. urealyticum detected in clinical samples.

Using the mba subtyping scheme (17), a single (dominant) mba subtype was identified in each of the 33 cultured clinical samples that were tested (Table 1). Ureaplasmas of the parvo biovar were clearly the most prevalent, being detected in 31 of the 33 samples tested. The subtypes mba 3a and mba 1a were detected most frequently in this population. Subtype mba 3a was detected in 13 clinical samples from eight different patients, and subtype mba 1a was identified in 7 samples from four different women (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Dominant mba subtype detected by direct sequencing of the mba gene fragment of each cultured clinical specimen

| mba subtype | Biovara | No. of isolates (n = 33) | No. of patients positive for subtype (n = 17) | Clinical specimen(s)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Parvo | 7 | 4 | 924e1, 924p, 1012e2, 1020e2, 1040v1, 1040e2, 1040p |

| 1b | Parvo | 1 | 1 | 1110e1 |

| 3a | Parvo | 13 | 8 | 912v1, 912e2, 921p, 928e1, 928e2, 928p, 931e1, 931e2, 1004e1, 1032e1, 1032e2, 1128v1, 1140e1 |

| 3b | Parvo | 2 | 1 | 1158v2, 1158e2 |

| 3c | Parvo | 1 | 1 | 912p |

| 3d | Parvo | 1 | 1 | 1044e1 |

| 6a | Parvo | 3 | 2 | 921e1, 921e2, 1012e1 |

| 6b | Parvo | 3 | 1 | 1043e1, 1043e2, 1043p |

| 8a | T960 | 1 | 1 | 1110p |

| X | T960 | 1 | 1 | 1016e1 |

Based on mba PCR—403-bp product for parvo biovar; 448-bp product for T960 biovar.

The nomenclature of clinical isolates is as follows. The first number is the designated patient number (one, two, or three specimens were collected from each patient). The letter indicates the site from which the specimen was collected (v, vagina; e, endocervix; p, placenta). The number at the end indicates the time of collection of the lower genital tract specimen (1, first antenatal visit; 2, 28 weeks of gestation).

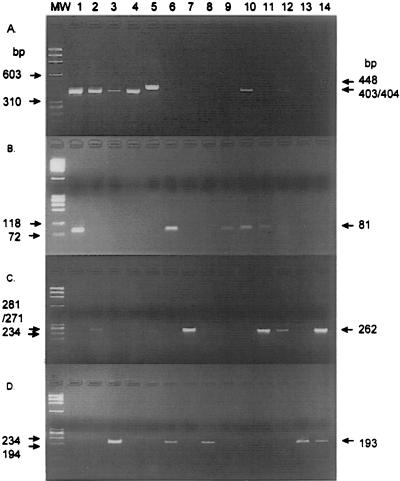

Single-step mba PCR of cultures.

The mba 1 primer pair (UMS-83 and UMA-41) amplified an 81-bp product from reference serovar 1 and from nine clinical isolates, the mba 3 primer pair (UMS-81 and UMA144) amplified a 262-bp product from serovar 3 and from 13 clinical isolates (excluding serovar 14), and the mba 6 primer pair (UMS-53 and UMA122) produced a 193-bp fragment from serovar 6 and from 10 clinical isolates (Table 2; Fig. 1). mba type 1, 3, and/or 6 of the parvo biovar was detected in 27 of the 28 clinical samples tested (Table 2) (5 samples were no longer available for testing). Single-step mba PCR not only detected the dominant U. urealyticum mba subtype; it also detected mixed mba types in five samples (921p, 924e1, 931e1, 1012e2, and 1040v1) (Table 2). The remaining sample (1110p) contained mba type 8, a biovar T960 U. urealyticum isolate which was previously identified by direct sequencing of the mba gene fragment.

TABLE 2.

Summary of mba and RAPD-PCR subtypes detected in clinical samples, and clinical history of each sample

| Patient no. | Gestation (wk)a | Isolate or reference serovar |

mba subtype(s)

|

RAPD-PCR subtype | Placental histology and culture historye | Maternal risk factor(s)f | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summaryb | Detected by:

|

|||||||

| Single-step PCRc | Nested PCRd | |||||||

| 921 | 34 | 921e1 | 6a | 6 | 6 | 10 | CAM, UU, AI, PROM > 1 wk | |

| 921e2 | 6a | 6 | NRg | 10 | ||||

| 921p | 3a, 6 | 3 and 6 | NR | NR | ||||

| 924 | 28 | 924e1 | 1a, 6 | 1 and 6 | 1 | NR | CAM, UU, GV | PPTD |

| 924p | 1a | 1 | NR | 1 | ||||

| 1004 | 36 | 1004e1 | 3a | 3 | Negative | 6 | PROM | Recurrent UTI |

| 1043 | 35 | 1043e1 | 6b | 6 | 6 | 12 | NSA | IVDU, previous CIN III |

| 1043e2 | 6b | 6 | 6 | 12 | ||||

| 1043p | 6b | 6 | NR | 12 | ||||

| 1110 | 35 | 1110e1 | 1b | 1 | 1 | 3 | CAM, UU | Previous HPV |

| 1110p | 8a | Negative | NR | 13 | ||||

| 1140 | 36 | 1140e1 | 3a, 6 | NR | 3 and 6 | NR | NSA | PPTD |

| 1158 | 32 | 1158v2 | 3b | 3 | 3 | 8 | PROM (32 wk) | Previous CIN III |

| 1158e2 | 3b | 3 | 3 | 8 | ||||

| 912 | 40 | 912v1 | 3a | 3 | 3 | 4 | NSA | Previous HCV, HPV |

| 912e2 | 3a | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 912p | 3c | 3 | NR | 9 | ||||

| 928 | 41 | 928e1 | 3a | 3 | 3 | 5 | AI, UU, funisitis | |

| 928e2 | 3a | 3 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| 928p | 3a | 3 | NR | 5 | ||||

| 931 | 40 | 931e1 | 1, 3a | 1 and 3 | 1 and 3 | NR | ||

| 931e2 | 1, 3a | NR | 1 and 3 | NR | ||||

| 1012 | 40 | 1012e1 | 6a | 6 | 6 | 11 | ||

| 1012e2 | 1a, 6 | 1 and 6 | NR | NR | ||||

| 1016 | 38 | 1016e1 | 1, X | NR | 1 | NR | CAM, UU | |

| 1020 | 40 | 1020e2 | 1a | 1 | 1 | NR | NSA | |

| 1032 | 41 | 1032e1 | 3a | 3 | NR | 7 | NSA | |

| 1032e2 | 3a | 3 | 3 | 7 | ||||

| 1040 | 40 | 1040v1 | 1a, 6 | 1 and 6 | 1 | NR | AI, UU, funisitis | Previous CIN II |

| 1040e2 | 1a | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 1040p | 1a | 1 | NR | 2 | ||||

| 1128 | 40 | 1128v1 | 3a | NR | 3 | NR | ||

| 1044 | Unknown | 1044e1 | 3d, 6 | NR | 3 and 6 | NR | PVC | |

| NAh | Serovar 1 | 1a | 1 | 1 | NR | |||

| NA | Serovar 3 | 3a | 3 | 3 | NR | |||

| NA | Serovar 6 | 6a | 6 | 6 | NR | |||

| NA | Serovar 14 | 3d | Negative | Negative | NR | |||

Deliveries at <37 weeks were considered preterm.

Includes cultured and original specimens. Determined by direct sequencing of the mba fragment or by single-step or nested mba PCR.

Determined with cultured specimens, using primer pairs for mba 1, 3, and 6.

Determined with original specimens, using outer-primer pair UM-1 and inner primers for mba 1, 3, and 6.

Determined if tissue was available. Abbreviations: CAM, chorioamnionitis; UU, U. urealyticum; AI, ascending infection; PROM, prolonged rupture of membranes; GV, Gardnerella vaginalis; NSA, no significant abnormality.

Abbreviations: PPTD, previous preterm delivery; UTI, urinary tract infection; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; IVDU, intravenous drug user; HPV, human papillomavirus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PCM, previous viral cardiomyopathy.

NR, no result (test not performed).

NA, not applicable.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products generated by mba outer primers UMS-125 and UMA226 (lanes 1 to 5, 10, and 12 only) (A), mba 1 primers UMS-83 and UMA-41 (B), mba 3 primers UMS-81 and UMA144 (C), and mba 6 primers UMS-53 and UMA122 (D). Lanes: 1 to 4, controls (serovars 1, 3, 6, 14, and 8, respectively); 6 to 14, samples 1040v1 (culture), 928e1 (culture), 1043e1 (culture), 1020e2 (culture), 1020e2 (original specimen), 931e1 (culture), 931e1 (original specimen), 921e1 (culture), and 921p (culture), respectively; MW, DNA molecular size markers (72 to 1,353 bp; Boehringer).

Nested mba PCR of original clinical specimens.

During the prospective study, original vaginal and endocervical samples were stored (16) at −70°C. (No placental samples were stored.) These original lower genital tract specimens were tested by nested mba PCR. At the time of testing, 23 original specimens (of the 26 lower genital tract samples investigated in this study) were available for testing; the other 3 original specimens had been used previously. The results of the nested mba PCRs were consistent with the results obtained by mba gene fragment sequencing and by single-step mba PCR of cultured specimens (Table 2). For 18 of these 23 samples, both single-step mba PCR results (on cultured specimens) and nested mba PCR results (on original specimens) were available. Different results were obtained for three samples (924e1, 1004e1, and 1040v1); the nested PCR did not detect an mba type, but it was subsequently detected after culture of the specimen. Nested mba PCR confirmed the presence of the mba subtype detected by direct sequencing of the mba fragment in four of the remaining five original samples and identified mixed mba types in a further three samples (931e2, 1044e1, and 1140e1). We also showed that sample 1016e1 was a mixture containing mba type 1 (detected by nested PCR) and mba X, a T960 biovar isolate. This result is interesting since the parvo biovar mba type 1 was not detected in the cultured specimen by the UM-1 primer pair because only a single product of 448 bp (T906 biovar) was amplified. This suggests that only very small numbers of type mba 1 cells were present in the original specimen.

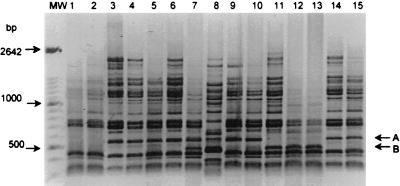

RAPD-PCR subtypes of U. urealyticum.

RAPD-PCR profiling was performed on 22 cultured clinical U. urealyticum isolates. Only available samples that contained a single mba subtype were tested. The 14 arbitrary 10-base primers generated two broadly distinct profiles which clearly differentiated the parvo biovar (21 isolates) from the T960 biovar (a single isolate, 1110p) (Fig. 2). The parvo biovar isolates were further distinguished by polymorphic bands generated by seven of these arbitrary primers (FPK 2-01, 2-07, 2-09, 2-11, 2-12, 2-17, and 2-18). Each of these primers was retested to ensure reproducibility of results. Figure 2 shows a typical profile and polymorphic bands generated with the primer FPK 2-11. All of the profiles generated were examined visually, and polymorphic bands were scored (as present or absent). The parvo biovar ureaplasmas were differentiated into 13 RAPD subtypes on the basis of nine polymorphic bands (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

RAPD-PCR profiles (negative image of 1.5% agarose gels) of 15 U. urealyticum clinical isolates, obtained by using arbitrary primer FPK 2-11. Lanes 1 to 15, 921e1, 921e2, 924p, 928e1, 928e2, 928p, 1110e1, 1110p, 1158v2, 1158e2, 1043e1, 1043e2, 1043p, 1040e2, and 1040p, respectively. Lane 8 contains the single T960 biovar isolate. Bands A (480 bp) and B (560 bp) are the polymorphic bands scored in Table 3. MW, DNA molecular size marker XIV (Boehringer).

TABLE 3.

RAPD-PCR-scored polymorphisms of the clinical isolates

| Isolate | Polymorphic band(s) generated by arbitrary primera:

|

RAPD subtype | mba subtype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-01

|

2-07 (A) | 2-09 (A) | 2-11

|

2-12 (A) | 2-17 (A) | 2-18 (A) | |||||

| A | B | A | B | ||||||||

| 924p | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | 1 | 1a |

| 1040e2 | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | 2 | 1a |

| 1040p | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | 2 | 1a |

| 1110e1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | 3 | 1b |

| 912v1 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | 4 | 3a |

| 912e2 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | 4 | 3a |

| 928e1 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | 5 | 3a |

| 928e2 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | 5 | 3a |

| 928p | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | 5 | 3a |

| 1004e1 | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | 6 | 3a |

| 1032e1 | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | 7 | 3a |

| 1032e2 | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | 7 | 3a |

| 1158v2 | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | 8 | 3b |

| 1158e2 | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | 8 | 3b |

| 912p | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | 9 | 3c |

| 921e1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | 10 | 6a |

| 921e2 | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | 10 | 6a |

| 1012e1 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | 11 | 6a |

| 1043e1 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | 12 | 6b |

| 1043e2 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | 12 | 6b |

| 1043p | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | 12 | 6b |

| 1110p | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | 13 | 8a |

Polymorphic bands were scored as present (+) or absent (−).

RAPD-PCR subtyping was more discriminatory than mba subtyping, since the 22 clinical isolates were divided into 8 mba subtypes and 13 RAPD subtypes (Table 3). Three of the mba subtypes (1a, 3a, and 6a) comprised more than one RAPD subtype (Table 3). As expected, no RAPD subtype was found in more than one mba subtype.

Relationship of U. urealyticum subtypes to adverse pregnancy outcome.

In the present study, we have subtyped clinical isolates collected from pregnant women in a previous prospective study. mba and RAPD-PCR subtyping showed that eight of these pregnant women were colonized in the lower genital tract with the same ureaplasma subtype(s) from early midtrimester until 28 weeks of gestation. The same mba and/or RAPD subtype(s) was isolated at these two time points from patients 912, 921, 928, 931, 1012, 1032, 1040, and 1043 (Table 2). Furthermore, the ureaplasma subtypes that were isolated from the lower genital tracts of patients 928, 1040, and 1043 during pregnancy were subsequently detected in their placental samples after delivery. An additional subtype was introduced to the lower genital tract of patient 1012 during the pregnancy and was detected at 28 weeks of gestation; a subtype present at the first antenatal visit of patient 1040 was not subsequently detected at 28 weeks.

Using single-step mba and nested mba PCR, we detected mixed U. urealyticum types in 9 of the 33 clinical samples tested (with 42 isolates being detected in total) and established that 10 women (patients 912, 921, 924, 931, 1012, 1016, 1040, 1044, 1110, and 1140) of the 17 tested in this study harbored more than one mba subtype in the lower genital tract or the placenta.

A comparison of the prevalences of the parvo biovar mba types in women who delivered preterm and those who delivered at term revealed that mba type 6 was detected significantly more often (P = 0.048) in the former (57.2%) than in women with term deliveries (22.2%) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Prevalences of parvo biovar mba types in women who delivered preterm and those who delivered at term

| mba type | No. (%) of mba type in women delivering:

|

Total no. (%) of mba type in all women tested (n = 17)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm (n = 7) | At term (n = 9) | ||

| 1 | 2 (28.6) | 5 (55.5) | 7 (43.8) |

| 3 | 4 (57.2) | 5 (55.5) | 10 (58.8) |

| 6 | 4 (57.2) | 2 (22.2)b | 7 (43.8) |

This total includes mba types from an additional patient whose gestation details are unknown.

P = 0.048.

Seven placental samples in total were subtyped in this study (Table 2). In five of these placentas (patients 921, 924, 928, 1040, and 1110) there was histological evidence of infection. Three women who delivered preterm (patients 921, 924, and 1110) were diagnosed with chorioamnionitis, and mba subtypes 1a, 3a, 6, and 8a were detected in their placental samples. Mixed subtypes (3a and 6) were detected in sample 921p. Ascending infection and funisitis were histologically diagnosed in two placentas (patients 928 and 1040), and mba subtypes 1a and 3a were detected. In the remaining two placentas (patients 912 and 1043), no significant abnormalities were diagnosed; however, mba subtypes 3c and 6d were detected. Different RAPD subtypes (1, 2, 5, 9, 12, or 13) were isolated from each of the placental samples tested (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Previously we described a U. urealyticum subtyping scheme based on sequence variations of the mba gene and its upstream region (17). In the present study, we developed a more convenient, nonsequencing method of mba typing that will selectively detect U. urealyticum mba types 1, 3, and 6 in clinical samples by either a single-step or a nested mba PCR. We also developed a RAPD-PCR subtyping method for U. urealyticum. mba and RAPD-PCR subtyping are both high-resolution molecular techniques which we have used to further investigate the nature of lower and upper genital tract U. urealyticum infections in pregnant women.

We designed three primer pairs by exploiting the polymorphisms within the mba gene fragment (17). These primer pairs selectively amplified gene fragments from mba types 1, 3 (excluding serovar 14), and 6; detected mixed U. urealyticum infections; and were able to detect mba types 1, 3, and 6 in original clinical specimens when used in a nested PCR. The specificity of the PCR assays was confirmed by control reactions with reference serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14 and by the sizes of the amplified gene fragments. The advantage of this three-primer-set PCR assay is that it can detect mixed U. urealyticum infections in patients by both single-step mba PCR and nested mba PCR, whereas direct sequencing of the mba gene fragment detects only the dominant U. urealyticum strain present. Mixed serovars have previously been detected by serotyping ureaplasma colonies on primary isolation plates (22, 25). However, it has been suggested (25) that expanding a clinical sample by culture prior to subtyping (a requirement of other serotyping techniques) may prevent the detection of U. urealyticum serovars which are more fastidious and therefore grow more slowly or those that are present in lower concentrations. In the present study, in 15 of the 18 specimens tested, the same mba type(s) was detected by both single-step (cultured specimen) and nested mba (noncultured specimen) PCR (Table 2). However, in the remaining three specimens (924e1, 1004e1, and 1040v1), an mba subtype was detected by single-step PCR only after culture of the clinical specimen. Presently, when testing original samples by nested PCR, it is still necessary to confirm the presence of ureaplasmas by culture, since a visible amplification product is not always detected by gel electrophoresis after PCR with the outer primers and mba types other than mba 1, 3, and 6 may be present in the sample. However, by sequencing alternate locations within the mba gene and other clinical isolates and reference serovars, it should be possible to expand the assay to also detect serovar 14 and the T960 biovar U. urealyticum strains.

In the present study, we subtyped 33 clinical samples from 17 pregnant women and analyzed 42 different U. urealyticum isolates. Of these isolates, 95% (40 of 42) were of the parvo biovar and 40% (17 of 42) were of mba type 3, and 13 of these isolates had an mba 3a sequence identical to that of serovar 3. Of the 33 samples tested by mba PCR and/or nested mba PCR, 9 (27%) were shown to be mixtures of more than one ureaplasma subtype; these included eight lower genital tract samples and one placental specimen. In this study, clinical samples collected from 17 different women were tested, and 10 (59%) of these women were found to harbor mixed ureaplasma subtypes. These results are consistent with previous reports. Four previous studies, three using serotyping (9, 22, 24) and the other employing PCR (1), have shown that ureaplasmas of the parvo biovar are more frequently isolated from women (64 to 94% of all ureaplasmas isolated). These serotyping studies also demonstrated that serovar 3 is the most prevalent strain (28 to 83%) isolated from women and their partners (9, 22, 24) and that mixed serovars could be detected in 57.5% of couples (24). Furthermore, the detection of mixed ureaplasma subtypes in this study does not appear to be clinically significant, since mixed subtypes were detected in both women who delivered preterm (three of seven women) and those who delivered at term (four of nine women) and in only one of the five placental samples with histological evidence of infection.

We also used RAPD-PCR for subtyping. The 22 clinical samples (from 12 different patients) were separated into 13 RAPD subtypes on the basis of nine polymorphic bands which were generated by 7 of the 14 different arbitrary primers. Different ureaplasma RAPD subtypes were isolated from each of the 12 patients, with two RAPD subtypes being detected in one patient (no. 912). Grattard et al. (11, 12) and Kong et al. (18) have previously differentiated the two biovars by using ureaplasma reference serovars, and they also tested clinical isolates by RAPD-PCR. Grattard et al. (12) were able to demonstrate vertical transmission from mother to neonate. In the present study, RAPD-PCR was more discriminative than mba subtyping, since it clearly differentiated all of the ureaplasmas isolated from different women as different RAPD subtypes.

Previously, Cheng et al. (6, 7) analyzed 21 clinical isolates by immunoblotting with serotype 1-, 3-, and 6-specific monoclonal antibodies and 4 clinical isolates by immunoblotting with type 4-specific monoclonal antibodies. Unique immunoblot patterns were obtained for each clinical isolate, and none of the patterns was similar to any of those produced by the reference serovars. Our RAPD-PCR subtyping method was also able to identify unique host-specific ureaplasma strains. RAPD-PCR is therefore well suited to epidemiological studies for determining routes of transmission of infection; however, the technique is technically demanding, and a number of different primers must be screened in order to detect sufficient polymorphic bands for subtyping.

After establishing both mba and RAPD-PCR subtyping methods, a major goal of the study was to apply these techniques to answer a number of critical clinical questions. First, we sought to determine whether U. urealyticum was a persistent colonizer of the lower genital tract of pregnant women. Knox et al. (16) previously showed that of the pregnant women colonized with U. urealyticum, 88% were colonized in the lower genital tract at their first antenatal visit and again at 28 weeks of gestation. By subtyping clinical isolates collected from these same women at these different time points, we have demonstrated that U. urealyticum is a persistent colonizer of the lower genital tract. Each of the eight women investigated in this study (patients 912, 921, 928, 931, 1012, 1032, 1040, and 1043) was colonized by the same ureaplasma subtype at both time points. Interestingly, patient 931 was persistently colonized with two mba types (1 and 3a), and an additional transient ureaplasma type was detected in patients 1012 and 1040. Others (22) investigated the persistence of serotypes by comparing 67 ureaplasma strains that were isolated from 30 patients, and they too found that most patients harbored the same serotype in different samples.

Since only a small proportion of women colonized with ureaplasmas in the lower genital tract develop upper genital tract infections (16), it has been postulated that some ureaplasma strains may be more pathogenic than others and thus responsible for these invasive infections (5, 22, 24, 27, 28, 34). Previous studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of serovar 4 (22) and serovar 8 (24) U. urealyticum in women with a history of recurrent abortion and in infertile couples, respectively. Quinn et al. (28) also found that women who experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes exhibited significantly elevated mean titers to serovars 4 and 8. By contrast, in the present study we demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of mba type 6 in the seven women who delivered preterm than in the nine women with term deliveries. However, our sample size was very small, and this relationship should be investigated further in future, larger studies.

Despite the higher prevalence of mba type 6 in women delivering preterm and being able to subtype the clinical ureaplasma isolates into 5 mba types, 9 mba subtypes, and 13 RAPD subtypes, our results strongly suggested that no single ureaplasma subtype was responsible for all of the histologically diagnosed placental infections and/or adverse pregnancy outcomes which were observed. In this study we subtyped strains from seven placental samples, five of which were directly linked to infections of the placenta by histological examination, and detected eight different ureaplasma isolates but only five different mba subtypes: mba 1a (samples 924p and 1040p), mba 3a (921p and 928p), mba 3c (912p), mba 6 (921p and 1043p), and mba 8a (1110p) (Table 2). However, two of these mba subtypes (1a and 3a) of the parvo biovar were most frequently isolated in this study. Subtype mba 1a was isolated from 4 patients, and mba 3a was isolated from 8 patients (of 17) (Tables 1 and 2). Different RAPD subtypes (no. 1, 2, 5, 9, 12, and 13) were detected in the six placental samples tested (924p, 1040p, 928p, 912p, 1043p, and 1110p, respectively). The pathogenicity of ureaplasmas therefore does not appear to be limited to a particular subtype(s); rather, it appears that those subtypes most frequently isolated from pregnant women are also more often isolated from placental infections.

Finally, it is not known if upper genital tract infections are due to ascending invasive infections or to the presence of U. urealyticum in the endometrium at the time of implantation, with subsequent low-grade infection (5). In three of the placental samples (912p, 921p, and 1110p) we detected an mba subtype (mba 3c, mba 3a, and mba 8a, respectively) which was not present in the endocervical sample(s) collected from that patient earlier in her pregnancy (Table 2). Furthermore, subtype mba 6 was isolated from the endocervical sample of patient 1040 but was not subsequently present in the placental sample. It is therefore possible that the lower genital tract and the endometrium are separately colonized with the same and/or different ureaplasma subtypes and that ureaplasma subtypes were already present in the endometrium at the time of implantation and subsequently were responsible for infection of the placenta and the adverse pregnancy outcome. Subtyping of lower genital tract and placental U. urealyticum clinical isolates (from the same women) did demonstrate early ascending placental infections in two pregnant women (patients 928 and 1040). Both these women delivered at term, and it may well be that the ascending infections were due to the eventual loss of integrity of the placental membranes in late pregnancy.

It has been postulated that infection of the endocervical canal may cause cell damage which subsequently allows ascension of pathogens and normal vaginal flora to the endometrium (23). In the present study, we subtyped placental ureaplasma isolates from seven women. Four of these women had a past history of human papillomavirus infection (patients 912 and 1110) or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (patients 1040 and 1043) (Table 2). These women were possibly at greater risk of upper genital tract infection or colonization due to previous infections and/or medical interventions which could have damaged the endocervix and thus facilitated ascension of microorganisms. This finding might suggest that women with these risk factors should be screened for U. urealyticum during pregnancy and managed appropriately.

McGregor et al. (21) and Carey et al. (3) concluded that lower genital tract colonization is not predictive of adverse pregnancy outcome; however, others (5, 13, 16, 19, 20, 26) have demonstrated that upper genital tract infections are associated with adverse pregnancy outcome. In the present study, we have shown by molecular subtyping that different ureaplasma subtypes can be isolated from the lower and upper genital tracts and, therefore, lower genital tract ureaplasma subtyping is not necessarily predictive of upper genital tract ureaplasma subtypes. Furthermore, screening lower genital tract ureaplasmas to identify a more pathogenic ureaplasma is neither feasible nor warranted since no particular ureaplasma subtype(s) is consistently associated with upper genital tract infections. It is clear that U. urealyticum is responsible for serious infections in pregnant women, often with a sequela of adverse pregnancy outcome, but it may well be that upper genital tract infections occur predominantly in women with risk factors that predispose them to infection. Further studies which both detect and subtype ureaplasmas in placental samples, amniotic fluids, and laparoscopically collected upper genital tract specimens are necessary to resolve the incidence and etiology of upper genital tract infection and colonization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Giffard for critically appraising the manuscript, S. Mathews for technical advice and encouragement, E. Fowler for the RAPD-PCR methodology, N. Spencer (QUT School of Mathematical Sciences) for performing the statistical analyses, and the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Southern Queensland for the use of equipment during this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele-Horn M, Wolff C, Dressel P, Pfaff F, Zimmermann A. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum biovars with clinical outcome for neonates, obstetric patients, and gynecological patients with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1199–1202. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1199-1202.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard A, Gautier M, Mayau V. Detection and identification of mycoplasmas by amplification of rDNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;81:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90467-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey J C, Blackwelder W C, Nugent R P, Matteson M A, Rao A V, Eschenbach D A, Lee M L F, Rettig P J, Regan J A, Geromanos K L, Martin D H, Pastorek J G, Gibbs R S, Lipscomb K A. Antepartum cultures for Ureaplasma urealyticum are not useful in predicting pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:728–733. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90505-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassell G H, Waites K B, Crouse D T, Rudd P T, Canupp K C, Stagno S, Cutter G R. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum of the lower respiratory tract with chronic lung disease and death in very-low-birth-weight infants. Lancet. 1988;ii:240–244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassell G H, Waites K B, Watson H L, Crouse D T, Harasawa R. Ureaplasma urealyticum intrauterine infection: role in prematurity and disease in newborns. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:69–87. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X, Naessens A, Lauwers S. Identification and characterization of serotype 4-specific antigens of Ureaplasma urealyticum by use of monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2253–2256. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2253-2256.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng X, Naessens A, Lauwers S. Identification of serotype 1-, 3-, and 6-specific antigens of Ureaplasma urealyticum by using monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1060–1062. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1060-1062.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen C, Black F T, Freundt E A. Hybridization experiments with deoxyribonucleic acid from Ureaplasma urealyticum serovars I to VIII. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1981;31:259–262. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cracea E, Botez D, Constantinescu S, Georgescu-Braila M. Ureaplasma urealyticum serotypes isolated from cases of female sterility. Zentbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg Abt 1 Orig A. 1982;252:535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garland S M, Murton L J. Neonatal meningitis caused by Ureaplasma urealyticum. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:868–870. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198709000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grattard F, Pozzetto B, De Barbeyrac B, Renaudin H, Clerc M, Gaudin O G, Bebear C. Arbitrarily-primed PCR confirms the differentiation of strains of Ureaplasma urealyticum into two biovars. Mol Cell Probes. 1995;9:383–389. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1995.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grattard F, Soleihac B, De Barbeyrac B, Bebear C, Seffert P, Pozzetto B. Epidemiologic and molecular investigations of genital mycoplasmas from women and neonates at delivery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:853–858. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray D J, Robinson H B, Malone J, Thomson R B., Jr Adverse outcome in pregnancy following amniotic fluid isolation of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Prenatal Diagn. 1992;12:111–117. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harasawa R, Dybvig K, Watson H L, Cassell G H. Two genomic clusters among the 14 serovars of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:393–396. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison H R. Prospective studies of Mycoplasma hominis infection in pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 1983;10:S311–S317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knox C L, Cave D G, Farrell D J, Eastment H T, Timms P. The role of Ureaplasma urealyticum in adverse pregnancy outcome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;37:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1997.tb02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knox, C. L., P. Giffard, and P. Timms. The phylogeny of Ureaplasma urealyticum based on the mba gene fragment. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kong F, Zhu X, Zhou J, et al. Grouping and typing of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Natl Med J China. 1996;76:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kundsin R B, Driscoll S G, Monson R R, Yeh C, Biano S A, Cochran W D. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum in the placenta with perinatal morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:941–945. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404123101502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher C F, Haran M V, Farrell D J, Cave D G. Ureaplasma urealyticum chorioamnionitis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;34:477–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1994.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGregor J A, French J I, Richter R, Vuchetich M, Bachus V, Seo K, Hillier S, Judson F N, McFee J, Schoonmaker J, Todd J K. Cervicovaginal microflora and pregnancy outcome: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of erythromycin treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1580–1591. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90632-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naessens A, Foulon W, Breynaert J, Lauwers S. Serotypes of Ureaplasma urealyticum isolated from normal pregnant women and patients with pregnancy complications. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:319–322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.2.319-322.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institutes of Health. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 1991;18:46–64. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn P A, Arshoff L U. Serotypes of U. urealyticum found in fertile and infertile couples. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1986;5:S352. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn P A, Arshoff L U, Li H C S. Serotyping of Ureaplasma urealyticum by immunoperoxidase assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13:670–676. doi: 10.1128/jcm.13.4.670-676.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn P A, Butany J, Taylor J, Hannah W. Chorioamnionitis: its association with pregnancy outcome and microbial infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:379–387. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn P A, Gillan J E, Markestad T, St. John M A, Daneman A, Lie K I, Li H C S, Czegledy-Nagy E, Klein M. Intrauterine infection with Ureaplasma urealyticum as a cause of fatal neonatal pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1985;4:538–543. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198509000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinn P A, Shewchuk A B, Shuber J, Lie K I, Ryan E, Sheu M, Chipman M L. Serologic evidence of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection in women with spontaneous pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;145:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson J A, Howard L A, Zinner C L, Stemke G W. Comparison of 16S rRNA genes within the T960 and parvo biovars of ureaplasmas isolated from humans. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:836–838. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson J A, Stemke G W. Expanded serotyping scheme for Ureaplasma urealyticum strains isolated from humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:873–878. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.5.873-878.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson J A, Vekris A, Bebear C, Stemke G W. Polymerase chain reaction using 16S rRNA gene sequences distinguishes the two biovars of Ureaplasma urealyticum. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:824–830. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.824-830.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez P A, Regan J A. Vertical transmission of Ureaplasma urealyticum in full term infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:825–828. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepard M C, Lunceford C D. Differential agar medium (A7) for identification of Ureaplasma urealyticum (human T mycoplasmas) in primary cultures of clinical material. J Clin Microbiol. 1976;3:613–625. doi: 10.1128/jcm.3.6.613-625.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepard M C, Lunceford C L. Serological typing of Ureaplasma urealyticum isolates from urethritis patients by an agar growth inhibition method. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;8:566–574. doi: 10.1128/jcm.8.5.566-574.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng L-J, Zheng X, Glass J I, Watson H L, Tsai J, Cassell G H. Ureaplasma urealyticum biovar specificity and diversity are encoded in multiple-banded antigen gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.6.1464-1469.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Kuppeveld F J M, van der Logt J T M, Angulo A F, van Zoest M J, Quint W G V, Niesters H G M, Galama J M D, Melchers W J G. Genus- and species-specific identification of mycoplasmas by 16S rRNA amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2606–2615. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2606-2615.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waites K B, Crouse D T, Philips J B, Canupp K C, Cassell G H. Ureaplasmal pneumonia and sepsis associated with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatrics. 1989;83:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waites K B, Rudd P T, Crouse D T, Canupp K C, Nelson K G, Ramsey C, Cassell G H. Chronic Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis infections of the central nervous system in preterm infants. Lancet. 1988;i:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng X, Teng L-J, Watson H L, Glass J I, Blanchard A, Cassell G H. Small repeating units within the Ureaplasma urealyticum MB antigen gene encode serovar specificity and are associated with antigen size variation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:891–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.891-898.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng X, Watson H L, Waites K B, Cassell G H. Serotype diversity and antigen variation among invasive isolates of Ureaplasma urealyticum from neonates. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3472–3474. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3472-3474.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]