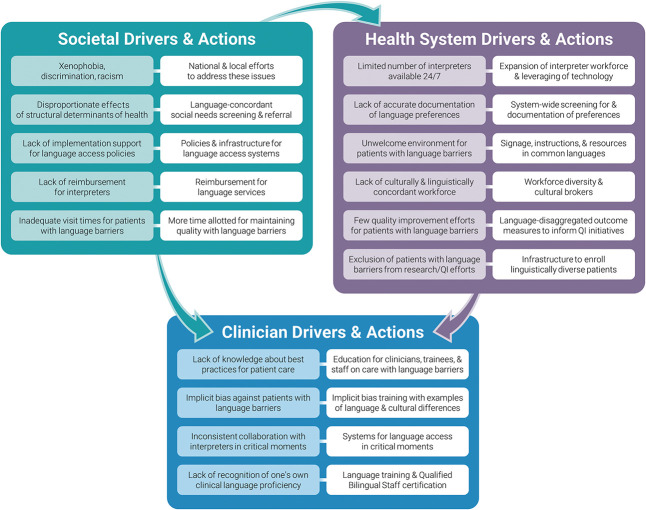

Improving effective, patient-centered communication with patients with language barriers requires action at the clinician, health system, and societal level.

Abstract

There is growing evidence that language discordance between patients and their health care teams negatively affects quality of care, experience of care, and health outcomes, yet there is limited guidance on best practices for advancing equitable care for patients who have language barriers within obstetrics and gynecology. In this commentary, we present two cases of language-discordant care and a framework for addressing language as a critical lens for health inequities in obstetrics and gynecology, which includes a variety of clinical settings such as labor and delivery, perioperative care, outpatient clinics, and inpatient services, as well as sensitivity around reproductive health topics. The proposed framework explores drivers of language-related inequities at the clinician, health system, and societal level. We end with actionable recommendations for enhancing equitable care for patients experiencing language barriers. Because language and communication barriers undergird other structural drivers of inequities in reproductive health outcomes, we urge obstetrician–gynecologists to prioritize improving care for patients experiencing language barriers.

There is growing evidence that language barriers and discordance between patients and their health care teams yield worse quality of care, experience of care, and health outcomes compared with language concordance, defined as when the clinician and patient communicate directly in the same language.1–5 Patients with language barriers also experience intersectionality with xenophobia, racism, and other systems of oppression that drive inequities in obstetrics and gynecology, such as lower rates of gynecologic cancer screening, higher rates of unscheduled cesarean birth and forced sterilization, and more experiences of obstetric trauma and mistreatment in childbirth, among minoritized individuals.6–11 Despite this evidence base, there is limited guidance on best practices for advancing equitable care for patients who have language barriers within obstetrics and gynecology.

In 2015, approximately 25 million people, or 9% of individuals older than age 5 years, reported having limited English proficiency (LEP) in the United States.12 An additional 11 million people with hearing loss, including those who use American Sign Language, require special considerations for effective communication.13 Language and communication barriers will continue to grow with immigration trends and the diversifying U.S. population. As codified in the Affordable Care Act's Section 1557 mandate for meaningful language access, patients experiencing language barriers have the right to dignified, high-quality care, including access to a qualified medical interpreter or qualified bilingual staff, defined as clinicians with professional proficiency in a patient’s preferred language.14,15 Consequently, health care professionals must attend to language differences to achieve the quintuple aim of health care delivery: patient experience, clinician experience, outcomes, cost, and health equity.16

In this commentary, we present two cases of language-discordant care followed by a proposed framework for addressing language as a critical lens for health equity in obstetrics and gynecology, a diverse field spanning labor and delivery, operating rooms, outpatient clinics, and inpatient services, in addition to requiring sensitivity around reproductive health topics. The proposed framework explores drivers of language-related inequities at the clinician, health system, and societal level. We end with actionable recommendations for enhancing equitable care for patients who have language barriers.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Case 1

A 29-year-old patient, gravida 1 para 0, who is undergoing labor induction for decreased fetal movement develops a nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing in the second stage of labor. The patient is Black and has documented Cape Verdean Creole language preference. A phone interpreter has been called intermittently during her labor, though not continuously throughout the second stage. The team experiences delays in counseling and consenting the patient for cesarean birth due to a more-than 20-minute wait for a Cape Verdean Creole interpreter. Neither a virtual interpreter tablet nor an in-person interpreter is available. The patient’s husband offers to interpret in the operating room. The team is faced with balancing the use of an ad hoc interpreter with limited availability of qualified interpreter services overnight in the labor and delivery department. The patient expresses dissatisfaction with her care team because she does not fully understand her birth experience.

Case 2

A 36-year-old patient, gravida 3 para 1, with abnormal bleeding due to leiomyomas is being treated with hormonal menstrual suppression. After counseling regarding options, she is sent home with instructions to take “5 mg norethindrone acetate once daily.” The patient is primarily Spanish-speaking, but there is no documentation in her record of whether her visit has been conducted with an interpreter or qualified bilingual staff. Her prescriptions are sent with instructions in English. At her follow-up visit, she reports she has been taking 11 pills of norethindrone acetate daily, because “once” means “11” in Spanish.

FRAMEWORK FOR ADDRESSING LANGUAGE-RELATED HEALTH INEQUITIES IN OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Our commentary examines factors that contribute to inequitable care for patients experiencing language barriers. The above cases highlight the multi-layered communication errors that occur when language discordance exists between patients and their health care teams.

Case 1 exemplifies the challenges that arise from a lack of qualified interpreters during critical points of care (ie, the second stage of labor and in the operating room), as well as the limited availability of interpreters, particularly in urgent or emergent situations, that may occur outside routine business hours. This case examines nuances of using ad hoc interpreters instead of qualified medical interpreters and challenges in balancing acuity and resource availability, especially for units that operate 24/7, such as labor and delivery. The case calls for introspection regarding implicit biases that affect when and how interpreters are called, especially when competing priorities exist. Lastly, it demonstrates that family interpreters are not always a reliable option and can lead to miscommunication in care due to 1) variable proficiency in both languages for accurate interpretation, 2) concerns with understanding medical terminology, 3) possible screening of information and incomplete interpretation, and 4) placing undue burden on family members, given their primary role as support people.

Case 2 captures a medication error due to instructions that were not translated into the patient's preferred language—a consequence of lack of adequate language access and lack of appropriate documentation of qualified bilingual staff or interpreter.

In presenting these cases, we hope to generate discussion, reflection, motivation, and action for improvement within obstetrics and gynecology. We introduce a framework that examines drivers of language-related health inequities and provides opportunities to advance equity for this population at the clinician, health system, and societal level (Fig. 1). We acknowledge the important role that clinicians play in advancing care for patients with language barriers, despite the constraints of societal- and health system–level barriers. At the clinician level, we aim to bring awareness to how our own behaviors may influence care for patients experiencing language barriers and how we can aim to change our practices to improve care and overcome these challenges. At the health system level, we highlight policies to improve care for patients experiencing language barriers. At the societal level, we describe the complex interplay of xenophobia and racism in influencing health outcomes for patients experiencing language barriers. Obstetrician–gynecologists can leverage their professional expertise to advocate for policy change and dismantle the underlying social determinants of health (SDOH) that drive health inequities for patients experiencing language barriers.

Fig. 1. Framework of drivers of language-based inequities and suggested actions at the societal, health system, and clinician levels. Barriers to language justice are outlined in the boxes shaded in color, and action items for success are highlighted in the white boxes.

Truong. Transcending Language Barriers in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 2023.

CLINICIAN LEVEL

Assessing Language Needs

Assessing patient language preference and the need for an interpreter is critical in providing equitable care. A focus group with 22 Spanish-speaking adults with LEP found that language-discordant clinicians often overestimated patients' understanding of English.17 Clinical team members should confirm patients' preferred spoken and written language for medical information. Additionally, clinicians should have a basic understanding of the regional variations in languages to be precise in calling for the appropriate interpreter. For example, Portuguese and Arabic diasporas have regional linguistic variations that could affect clinical communication if the correct interpreter is not requested. Language preferences should be documented in the medical record system and revisited on a regular basis to promote efficiency in obtaining appropriate interpreter services.

Appropriate Collaboration With Interpreters

Once a language need is identified, the clinical care team is responsible for calling the appropriate interpreter, which is often influenced by availability, acuity, and competing priorities. A cross-sectional study of communication practices during childbirth hospitalization showed that only 36% of clinicians appropriately collaborated with interpreters.8 Clinical care teams may have limited access to all modalities of interpreters based on the time of day and institutional contracts. In-person interpretation is typically preferred, especially for admission and confirmation of code status, assessment of trauma history, second stage of labor, procedures, acute events, delivery of bad news, and medication and care summary review at discharge.18 In some settings, however, patients may prefer telephone interpreters due to concerns about privacy during sensitive visits.19 Some patients may also have preferences regarding gender of interpreters, especially during pelvic examinations. Clinicians should always address the patient directly, allow time for interpretation, avoid idioms and jargon, and ascertain understanding by asking the patient to repeat back what they understood from the encounter.20

Use of ad hoc interpreters, such as family members, has been shown to increase communication errors.21 However, in situations involving an imminent threat to the safety or welfare of a patient, and when no qualified interpreter is immediately available, the current U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines do allow use of ad hoc interpreters.15 There may be times when the patient insists on their family member serving as their interpreter.22 Clinicians also have a right to a medical interpreter to ensure that their communication is complete and accurate. When there are discordant preferences between the patient and clinician regarding interpreters, we recommend a shared decision-making approach and documentation of this decision.

Compliance With Qualified Bilingual Staff Certification

Case 2 exemplifies how providing care in languages without appropriate professional proficiency (qualified bilingual staff certification, equivalent assessment, or completion of university-level education in the target language) can result in harm. Clinician overconfidence in language abilities has been associated with serious errors and poor-quality patient care.23 The nuances of language required to provide clear, compassionate communication and shared decision making may be missed in the absence of professional proficiency.20

When clinicians lack professional proficiency in a language, they should engage interpreters rather than relying on their own language skills. Although patients may appreciate their clinician's attempt to speak their preferred language and direct communication may be more efficient, conducting medical care without the appropriate proficiency level leads to differential quality of communication and potential errors. Communicating informally in the language to build rapport is encouraged, but topics related to medical care should be discussed with a professional medical interpreter to ensure accuracy and understanding. When providing care to patients experiencing language barriers, qualified bilingual staff certification or use of medical interpreters should be documented for quality assurance and improvement.20

HEALTH SYSTEM LEVEL

Adhering to National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

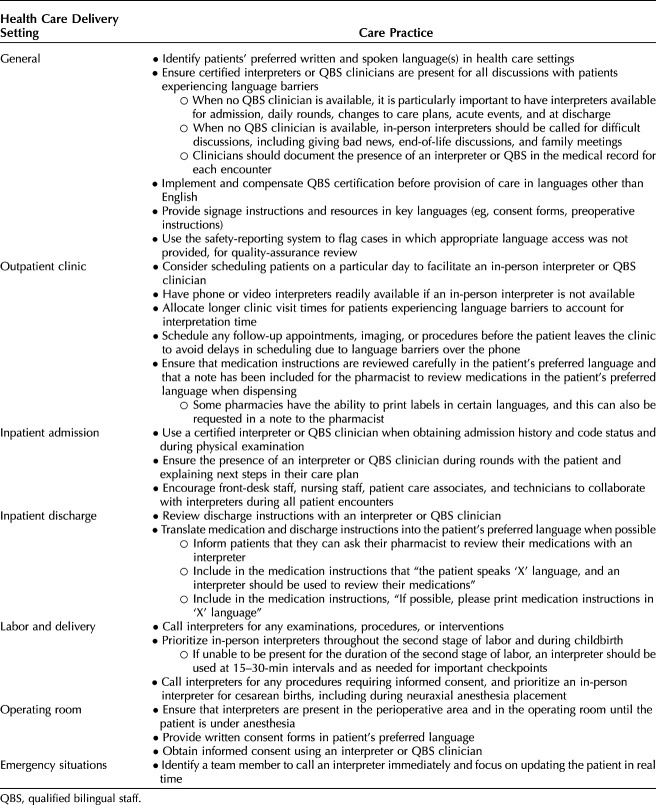

Developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards provide a blueprint to eliminate language-related health inequities, including: 1) offering language assistance to individuals who have language barriers or other communication needs at no cost, 2) informing individuals of the availability of language-assistance services, 3) ensuring the competence of individuals providing language assistance, and 4) providing print and multimedia materials and signage in commonly used languages. In a survey-based study of 239 hospitals across the United States, only 13% of hospitals met all four culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards; 19% met none of them.24 We recommend that institutions develop policies and systems to ensure language access across all health care delivery settings. Table 1 summarizes fundamental practices for equitable care for patients experiencing language barriers and highlights standards specific to obstetrics and gynecology in each of our care-delivery settings.

Table 1.

Fundamental Care Practices for Obstetrics and Gynecology Patients Experiencing Language Barriers

Promoting Language-Concordant Care and Cultural Brokering

To better meet these needs, health systems should prioritize understanding and documenting the unique make-up of languages spoken by patients in their catchment areas in a standardized, actionable manner. Institutions should implement and incentivize processes for health care staff to obtain qualified bilingual staff certification. Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts should also bolster the recruitment and retention of a multilingual clinician workforce and build a robust workforce of qualified medical interpreters—an opportunity to engage international medical graduates and newly arrived immigrants.25 Qualified bilingual staff can engage with patients without interpreters, not only reducing costs but also enhancing patient experience of care across all contacts with the health system, including front desk staff, medical assistants, pharmacists, hospital operators, and clinicians. When language concordance is not possible, cultural brokers—individuals who understand the cultural and structural contexts that influence a patient's experience—can be critical in mediating cultural and linguistic differences between patients and their care teams.26 Cultural brokers, such as some community-based doulas or patient navigators, improve patient experiences of care and may serve an important role on the health care team in navigating and overcoming language and cultural barriers.27 Collaborations between health systems and community-based organizations are critical for enhancing health for minoritized linguistic communities.

Prioritizing Language-Related Outcome Measures

Few institutions intentionally measure outcomes and experiences through the lens of language preference and proficiency. Furthermore, research and quality improvement often exclude patients experiencing language barriers by design, that is, only English-speaking patients are included as participants or team members. Lack of representation and inclusion in research further propagates language-related inequities in care.28 A recent review of 100 high-impact studies in obstetrics and gynecology demonstrated that LEP was an exclusion criterion for 31% of studies; only 1.3% of studies intentionally recruited patients with LEP.29 Patients experiencing language barriers should be included in all research studies and prioritized in health systems’ quality-improvement efforts.

Making language-concordant care a reportable quality measure is crucial to its prioritization in practice. As an example of this, a Greater Boston–based health system's United Against Racism equity improvement initiative has started measuring how often outpatient care is provided in a patient's preferred language. Preliminary data show that up to one in five encounters in selected practices were not conducted in the preferred language (internal equity data). These data allow for designing improvement efforts tailored to gaps in language access.

SOCIETAL LEVEL

Language Access Policies, Funding, and Reimbursement Structures

The legal foundation for language access was built in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which first prohibited discrimination “on the basis of race, color, or national origin” in any program or activity that receives federal funds, including Medicare and Medicaid.30,31 Executive Order 13166, signed in 2000, bolstered this law by explicitly stating that patients with LEP must be able to meaningfully access services; Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act provides specifications regarding these language-access requirements.32,33 The Language Access and Inclusion Act (Bill H3.199/S.2040) in Massachusetts is an example of a state-level policy that mandates that public-facing agencies provide adequate language-access plans and vital materials for the state's linguistically diverse population.34

Implementation of such language-access policies remains highly variable in health care systems. Currently, there is no requirement for private insurers to reimburse for language-access services; Medicaid will reimburse for these services only in some states.35 As a result, the costs associated with interpreter services fall on the health care system.36 Legal experts have suggested that reimbursement for interpreter services by the government or private payers or both is an important strategy, because this would help avoid the cost incurred by health care institutions aiming to comply with these policies.37 Some payers, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, have already developed initiatives that explicitly create payment structures for programs to advance health equity; expanding support for improved language access is a natural extension of these programs.38 Another strategy is to provide cost incentives for improving care for patients experiencing language barriers, exemplified by the Massachusetts Medicaid 1115 waiver, which includes financial incentives for the collection of patient language-preference data and for processes to qualify interpreters.39 In prioritizing value-based care, it is now possible to bill for total time spent on a visit, including longer visits spent with interpreter services.40 Redesigning reimbursement structures to prioritize language-related outcomes would mitigate financial barriers that currently disincentivize the additional time and effort needed to better care for patients with language barriers.

Point-of-care language access is ripe for innovation with interdisciplinary collaborations with linguists, technological advances in digital translation services, and novel applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence.41 Importantly, improving equitable care for patients experiencing language barriers may ultimately decrease health care costs by reducing readmission rates and preventable complications while encouraging efficient utilization of resources.42

Xenophobia, Discrimination, and Racism

Achieving equity for patients who have language barriers requires reflection and action to address the intersectionality of xenophobia, racism, and other systems of oppression. The long history of xenophobia and racism in the United States has been punctuated by recent xenophobic rhetoric and anti-immigrant policies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.43,44 ACOG Committee Statement No. 4 further highlights the harmful effects of anti-immigrant rhetoric and punitive immigration-enforcement activities on reproductive justice.6 When compared with patients who are fluent English speakers, patients with LEP are more likely to experience xenophobia and racism.6,45 Structural racism is increasingly documented in the field of obstetrics and gynecology, and recognition of xenophobia as a driver of worse health outcomes is growing.46–51 Adjacent efforts to dismantle racism, implicit bias, and xenophobia are needed to address inequities for patients who speak languages other than English. To enhance awareness, reflection, and action, health professional training curricula should include discussion of historical and contemporary policies and practices in the health care system that exclude immigrants and people who speak languages other than English.

Disproportionate Effects of Negative Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health—the social, economic, and political factors that contribute to inequities—are associated with poor maternal and neonatal outcomes, advanced-stage gynecologic cancer, and other adverse events.52–55 A large cohort study comparing SDOH screening results between English-speaking patients and patients with LEP demonstrated significantly higher social needs among patients with LEP in almost all of the dimensions queried, including material needs, employment, and food insecurity.56 Furthermore, Spanish-speaking patients had higher needs across all domains when compared with the population with LEP as a whole.56

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 729 describes the role of SDOH in reproductive health care and provides recommendations to obstetrician–gynecologists for addressing inequities. This opinion supports inquiring about SDOH, referring to social services when applicable, building partnerships with community-based organizations, and advocating for policies that contribute to societal change.57 Overcoming language barriers is paramount to creating a space for effective screening for social needs and making appropriate referrals. On a societal level, we need inclusive systems that allow people who speak languages other than English to access the full spectrum of services, including housing, employment assistance, immigration assistance, and nutrition programs.

CONCLUSION AND CALL TO ACTION

Language is a critical dimension of health equity. Obstetrician–gynecologists can be powerful advocates for change in their local teams and institutions and in society.58 We need innovation in designing health care–delivery systems—from payment reform to diversifying the health care workforce to expanding access to interpreters and cultural brokers—to deliver equitable care to a growing population of linguistically diverse patients.

Footnotes

Rose Molina reports she was supported by grant number K12HS026370 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Financial Disclosure Caroline Mitchell reports that she and her institution received payment from Scynexis, Inc., and she received payment from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Courtney Staples, who assisted with the graphic design of the framework figure.

The authors' Positionality Statement is available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D358.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D359.

REFERENCES

- 1.Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:60–7. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs ZG, Prasad PA, Fang MC, Abe-Jones Y, Kangelaris KN. The association between limited English proficiency and sepsis mortality. J Hosp Med 2020;15:140–6. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levas MN, Cowden JD, Dowd MD. Effects of the limited English proficiency of parents on hospital length of stay and home health care referral for their home health care–eligible children with infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:831–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levas MN, Dayan PS, Mittal MK, Stevenson MD, Bachur RG, Dudley NC, et al. Effect of Hispanic ethnicity and language barriers on appendiceal perforation rates and imaging in children. J Pediatr 2014;164:1286–94.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu T, Myerson R. Disparities in health insurance coverage and access to care by English language proficiency in the USA, 2006-2016. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:1490–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05609-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health care for immigrants. ACOG Committee Statement No. 4. Obstet Gynecol 2023;141:e427–33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs EA, Karavolos K, Rathouz PJ, Ferris TG, Powell LH. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1410–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanserino KA, Papatla K, Aioub M, Gee T, Datwani H. Quality of care and communication with limited English proficiency (LEP) obstetric patients [abstract 37J]. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:112–3s. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000664384.21313.1a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health 2019;16:77. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staniczenko AP, Antonio E, Bejerano S, Lantigua-Martinez MV, Ntoso A, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, et al. Disparities in type of delivery by patient preferred language. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226:S474–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sentell T, Chang A, Ahn HJ, Miyamura J. Maternal language and adverse birth outcomes in a statewide analysis. Women & Health 2016;56:257–80. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2015.1088114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connecticut State Department of Public Health. Individuals with limited English proficiency and literacy. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Public-Health-Preparedness/Access-and-Functional-Needs/Individuals-with-Limited-English-Proficiency-and-Literacy

- 13.Cornell University. Disability statistics from the American Community Survey, 2019. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.disabilitystatistics.org/reports/acs.cfm?statistic=1

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Section 1557 of the patient protection and affordable care Act. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/section-1557/index.html

- 15.Code of Federal Regulations. 45 CFR 92.4: Nondiscrimination in Health Programs and Activities. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-92

- 16.Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA 2022;327:521–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.25181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks K, Stifani B, Batlle HR, Nunez MA, Erlich M, Diaz J. Patient perspectives on the need for and barriers to professional medical interpretation. R Med J 2016;99:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Neveu M, Berger Z, Gross M. Lost in translation: the role of interpreters on labor and delivery. Health Equity 2020;4:406–9. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia EA, Roy LC, Okada PJ, Perkins SD, Wiebe RA. A comparison of the influence of hospital-trained, ad hoc, and telephone interpreters on perceived satisfaction of limited English-proficient parents presenting to a pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004;20:373–8. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000133611.42699.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juckett G, Unger K. Appropriate use of medical interpreters. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:476–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:545–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray B, Hilder J, Donaldson H. Why do we not use trained interpreters for all patients with limited English proficiency? Is there a place for using family members? Aust J Prim Health 2011;17:240–9. doi: 10.1071/PY10075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maul L, Regenstein M, Andres E, Wright R, Wynia MK. Using a risk assessment approach to determine which factors influence whether partially bilingual physicians rely on their non-English language skills or call an interpreter. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2012;38:328–36. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38043-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA. Do hospitals measure up to the national culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards? Med Care 2010;48:1080–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molina RL, Kasper J. The power of language-concordant care: a call to action for medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:378. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1807-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: the essential role of cultural broker programs. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/culturalbroker/Cultural_Broker_EN.pdf

- 27.Lo MC. Cultural brokerage: creating linkages between voices of lifeworld and medicine in cross-cultural clinical settings. Health (London) 2010;14:484–504. doi: 10.1177/1363459309360795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glickman SW, Ndubuizu A, Weinfurt KP, Hamilton CD, Glickman LT, Schulman KA, et al. Perspective: the case for research justice: inclusion of patients with limited English proficiency in clinical research. Acad Med 2011;86:389–93. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318208289a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulhall JC, Zhao Z, Limperg T. Inclusion of limited English proficiency individuals in obstetric randomized controlled trials [abstract A161]. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139:47S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000825920.03113.63 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.justice.gov/crt/fcs/TitleVI

- 31.Chen AH, Youdelman MK, Brooks J. The legal framework for language access in healthcare settings: Title VI and beyond. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:362–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0366-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice. Executive Order 13166: Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency (2000). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.justice.gov/crt/executive-order-13166

- 33.American Medical Association. Affordable Care Act, Section 1557: fact sheet. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/media/14241/download

- 34.The Language Access for All Coalition. An act relative to language access and inclusion. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://massappleseed.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Language-Access-Inclusion-Bill-Fact-Sheet-v.8-1.pdf

- 35.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Section 1557: frequently asked questions. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/section-1557/1557faqs/index.html#_ftnt8

- 36.Shah SA, Velasquez DE, Song Z. Reconsidering reimbursement for medical interpreters in the era of COVID-19. JAMA Health Forum 2020;1:e201240. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youdelman MK. The medical tongue: U.S. laws and policies on language access. Health Aff 2008;27:424–33. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blue Cross Blue Shield. National health equity strategy. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/healthequity/strategy

- 39.MassHealth. Fact sheet: MassHealth’s newly approved 1115 demonstration extension supports accountable care and advances health equity. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.mass.gov/doc/1115-waiver-extensionfact-sheet/download

- 40.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Evaluation and management changes for 2021. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.acog.org/practice-management/coding/coding-library/evaluation-and-management-changes-for-2021

- 41.Chang DT, Thyer IA, Hayne D, Katz DJ. Using mobile technology to overcome language barriers in medicine. Ann R Coll Surgeons Engl 2014;96:e23–5. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184903685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngai KM, Grudzen CR, Lee R, Tong VY, Richardson LD, Fernandez A. The association between limited English proficiency and unplanned emergency department revisit within 72 hours. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.02.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samari G, Nagle A, Coleman-Minahan K. Measuring structural xenophobia: US State immigration policy climates over ten years. SSM - Popul Health 2021;16:100938. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gover AR, Harper SB, Langton L. Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the reproduction of inequality. Am J Criminal Justice 2020;45:647–67. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gee GC, Ponce N. Associations between racial discrimination, limited English proficiency, and health-related quality of life among 6 Asian ethnic groups in California. Am J Public Health 2010;100:888–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryant A. Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetric and gynecologic care and role of implicit biases. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-obstetric-and-gynecologic-care-and-role-of-implicit-biases

- 47.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Mayes N, Johnston E, et al. . Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011-2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:423–29. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6818e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander AL, Strohl AE, Rieder S, Holl J, Barber EL. Examining disparities in route of surgery and postoperative complications in Black race and hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:6–12. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grobman WA, Parker CB, Willinger M, Wing DA, Silver RM, Wapner RJ, et al. Racial disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes and psychosocial stress. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:328–35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suleman S, Garber KD, Rutkow L. Xenophobia as a determinant of health: an integrative review. J Public Health Policy 2018;39:407–23. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0140-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardeman RR, Kheyfets A, Mantha AB, Cornell A, Crear-Perry J, Graves C, et al. Developing tools to report racism in maternal health for the CDC maternal mortality review information application (MMRIA): findings from the MMRIA racism & discrimination working group. Matern Child Health J 2022;26:661–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03284-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.AAFP. Advancing health equity by addressing the social determinants of health in family medicine (position paper). Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/social-determinants-health-family-medicine-position-paper.html

- 53.Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Helpman L, Pond GR, Elit L, Anderson LN, Seow H. Endometrial cancer presentation is associated with social determinants of health in a public healthcare system: a population-based cohort study. Gynecol Oncol 2020;158:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. J Women’s Health 2021l;30:230–5. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer A, Conigliaro J, Allicock S, Kim EJ. Examination of social determinants of health among patients with limited English proficiency. BMC Res Notes 2021;14:299. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05720-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 729. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e43–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Policy priorities. Accessed January 30, 2023 https://www.acog.org/advocacy/policy-priorities