Abstract

Introduction

The ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ Project aims to support the scale-up of integrated care for diabetes and hypertension in Cambodia, Slovenia and Belgium through the co-creation, implementation and evaluation of contextualised roadmaps. These roadmaps offer avenues for action and are built on evidence as well as stakeholder engagement in policy dialogues. Roadmaps and policy dialogues are very much intertwined and considered to be key elements for successful stakeholder-supported scale-up in integrated chronic care. Yet, little is known about how, why and under which conditions policy dialogue leads to successful roadmap implementation and scale-up of integrated care. Therefore, this study aims to use a realist approach to elicit an initial programme theory (IPT), using political science theories on the policy process.

Methods

To develop the IPT, information from different sources was collected. First, an exploratory literature review on policy dialogue and scale-up definitions and success factors was performed, identifying theoretical frameworks, empirical (case) studies and realist studies (information gleaning). Second, research workshops on applying theory to the roadmap for scale-up (theory gleaning) were conducted with a multidisciplinary expert team. We used the intervention–context–actors–mechanism–outcome configuration to synthesise information from the sources into a configurational map.

Results

The information and theory gleaning resulted into an IPT, hypothesising how policy dialogues can contribute to roadmap success in different policy stages. The IPT draws on political science theory of the multiple streams model adapted by Howlett et al to include five streams (problem, solution, politics, process and programme) that can emerge, converge and diverge across all five policy stages.

Conclusion

This paper aims to extend the knowledge base on the use of policy dialogues to build a roadmap for scale-up. The IPT describes how (dynamics) and why (theories) co-created roadmaps are expected to work in different policy stages.

Keywords: health policy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Success factors of policy dialogues and scale-up have been empirically researched, but without the combination of a realist lens and political science theories.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This paper aims to extend the theoretical knowledge base on the use of policy dialogues to build a roadmap for scale-up of integrated care by developing an initial programme theory (IPT) based on the multiple streams model (MSM).

The IPT describes how (dynamics) and why (theories) a roadmap developed in policy dialogues is expected to work, hypothesising that roadmap success (ie, scale-up) occurs when there is convergence of (and agency within) the problem, solution, process, politics and programme streams.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

By testing theories in real cases, theories such as the MSM can be adapted, refuted and/or reconstructed to elicit a refined theory of how and why a co-created roadmap for scale-up works in different policy stages.

With the MSM as starting point for the formulation of an IPT, we hypothesise that scaling requires convergence of diverse stakeholder groups, via stakeholder engagement in policy dialogues and the development of an evidence-based roadmap; both scale-up strategies can act as bridges to bring diverse actors together.

Introduction

Despite global commitments to integrated care (IC), which ensures a continuum of care services from disease prevention to management leading to improved (cost) efficiency, quality of care and patient outcomes,1–3 countries are struggling to scale up IC sustainably and effectively.4–6 Scaling up is a transformation process of changing complex systems,7 requiring multicomponent efforts that need to be tailored to the contexts in which they are delivered.8 Scaling up a complex intervention such as IC is especially all the more challenging, given that care for chronic diseases requires multistakeholder action and intersectoral coordination at the healthcare practice level, as well as at organisational and political/system levels.8 9 In view of these challenges, there is an urgent need to better understand the various strategies on how to scale up.6 8 Examining such IC strategies, policy plans or ‘roadmaps’ is crucial for enhancing scale-up efforts as well as chronic disease control and health system strengthening.

Stakeholders play a key role in the scale-up process and can influence IC scale-up at different stages of the policy cycle: agenda-setting, policy formulation, adoption, implementation and evaluation.10 Complexity in the scale-up process arises from the expression of their power relations, their varying opposing positions and conflictual interests, which typically translate into a political struggle, that is, agonistics, within a world of societal contingencies.11 Since these stakeholders’ (attributes of) power, position and interest as well as their perceptions and interpretations of IC and scale-up have a ‘real’ impact on the material and social world,12 13 strategies for scale-up need to take stakeholder views into account to enable effective and sustainable implementation.9

Hence, scaling up does not only entail roadmap planning and implementation processes (dynamics of ‘how to’) as a mere technocratic exercise but also harbours the intricate relationships and interactive processes between a wide range of stakeholders engaging as agents for change in policy dialogues, negotiating the terms, conditions, resources and rationale (‘why’) of scale-up.14

Roadmaps and policy dialogues—considered two complex-intervention components in this study—are very much intertwined and considered to be key elements for successful stakeholder-supported scale-up.14 A roadmap can be described as: ‘a strategy and implementation plan that considers the policy context, delivery mechanisms and resource requirements, as well as the pace of change, sequencing of activities, areas for prioritisation and monitoring and evaluation’.15 More specifically, it is an action plan delineating targets, planning and progression of scale-up strategies, and identifying actors, actions, timelines, based on priorities in place and time.6 Rajan et al describe a policy dialogue as: ‘an essential component of the policy and decision-making process, where it is intended to contribute to informing, developing or implementing a policy change following a round of evidence-based discussions, workshops, and consultations on a particular subject.16 It is seen as an integrated part of the policymaking process, and can be conducted at any level of the health system where a problem is perceived and a decision, policy, plan or action needs to be made.’ Roadmaps are often co-created17–19 or co-produced19–24 in policy dialogues. The policy dialogue is intended to provide a space where knowledge can be shared and mobilised,20 25 hence the deliberate26 and collaborative quality,27 28 while stimulating stakeholder participation and engagement.

Research gap and aim of this paper

Building on the principles of co-creation, the process of roadmap development, adoption and implementation is a complex social and political process involving power sharing, valuing the perspectives and experiences of stakeholders, and building trusting relationships.20 29 30 As the area of knowledge co-production (or co-creation) in health policy is theoretically underdeveloped,31–34 greater attention to Health Policy and Systems Research is needed to understand actual processes of actor engagement, such as policy dialogues, and to establish stronger evidence linking co-creation models and outcomes. Little is known so far about what makes a co-created scale-up roadmap successful (or not); or more specifically, what it is that works, how and why it works, for whom and under what circumstances. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to elicit an initial programme theory (IPT), as the first phase of a realist evaluation, exploring how, why and under which circumstances policy dialogue leads to successful roadmap adoption, implementation and scale-up of IC.

This study is situated within the ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ (SCUBY) Project, which aims to facilitate scale-up of IC for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and hypertension (HT) through the co-creation, implementation and evaluation of contextualised scale-up roadmaps in Cambodia, Slovenia and Belgium.6

In the following sections, we will describe the study context in more detail as well as the methods used, including a description of the realist methodology and the stepwise approach towards IPT elicitation.

Study context

In this research, we developed a theory on the policy process for the scale-up of IC and we will subsequently study these processes in different contexts, in three countries with different health systems where differing healthcare practices delivering chronic care are nested in differing sociopolitical systems: a developing health system in a lower-middle-income country (LMIC; Cambodia); a centrally steered health system in a high-income country (HIC; Slovenia); and a publicly funded highly privatised healthcare system in an HIC (Belgium). Each country is a case of scale-up of IC for T2D and HT.

The selection of the three cases was based on their health system characteristics and current policy focus on scale-up strategies. These scale-up strategies can include efforts to: (1) increase population coverage, (2) integrate or institutionalise IC into health system services and (3) expand the IC package, that is, diversify IC with additional components.4 Scale-up is a multidimensional concept and may involve various efforts in each country to make progress on any of these three axes (see online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjgh-2023-012637supp001.pdf (443.6KB, pdf)

In the three settings, the scale-up activities as part of the roadmap are specifically targeted towards improving primary (low-level) care.6 The context-specific scale-up roadmaps (are intended to) offer avenues of action and policy direction and are built on two pillars: (1) evidence and (2) stakeholder engagement in policy dialogue. First, the evidence pillar within the roadmap consists of the findings of the formative phase in the SCUBY Project (in which current IC implementation was assessed via interviews and focus groups). Stakeholder engagement in policy dialogues is a second important pillar stone of the roadmap, as a relevant way to receive inputs and feedback, and further refine policy directions while co-creating the key recommended strategies. Because of this ongoing engagement with stakeholders in policy dialogues, the roadmap (intervention) can continue to be adapted over time. The relation between roadmap, evidence and policy dialogue as conceptualised within the SCUBY Project is clarified in online supplemental appendix 2.

bmjgh-2023-012637supp002.pdf (224.9KB, pdf)

Methods

The main research question of this study is: ‘How, why and under which circumstances does policy dialogue lead to roadmap success (adoption/implementation)?’. A realist approach was used to guide this study, which is concerned with the first phase of realist evaluation aiming to elicit an IPT.

Realist evaluation

Realist evaluation uses theory to delve deeper into generative causation and seeks to understand how, why, for whom and under what circumstances a programme works (or not).35 36 Realist evaluation is in the family of theory-driven evaluation, with realism as its philosophical foundation. The role of theory and theory refinement is essential within realist evaluation, as a realist approach assumes that programmes are ‘theories incarnate’.13 The overall aim in the realist methodology is to adapt, refute and/or refine programme theories. Within realist inquiry, we typically start from an initial hypothesis (or hypotheses) about the intervention, programme or policy under study, namely the IPT. A programme theory can be described as ‘a set of explicit or implicit assumptions of how the programme should be organised and why the programme is expected to work’.37 Programme theories explain how and why the desired change is expected to take place by linking programme activities to outcomes via mechanisms.38 They should be concrete enough to be tested and refined through empirical research, and abstract enough to generalise from the case-specific theories.39 Middle-range theories (MRTs) play a crucial bridging role between raw empirical observations and all-encompassing grand-theoretical schemes.40 Aside from advancing theoretical and scientific knowledge in the process of refining programme theories via testing them in various real-world cases, at the lower, more practical level, realist evaluation aims to identify the underlying causal relations between context, mechanism and outcome (CMO).41 Pawson and Tilley used the understanding that within a certain context, programme mechanisms and pre-existing mechanisms get triggered to cause the observed outcomes or observation.35 This understanding gave rise to the CMO heuristic tool as a configurational tool for realist informed theory formulation to capture or represent generative causation underlying the programme theory. Context is multilayered and programmes are embedded in them.42 Outcomes are by Pawson and Tilley referred to as semiregular patterns of change in participant attitudes, knowledge and behaviour.35 42 Stated differently, outcomes are the practical effects produced by causal mechanisms being triggered in a given context.

A realist mechanism is less easily defined.42 According to Pawson and Tilley, mechanisms are a combination of resources (eg, components of an intervention) and reasoning and/or responses (eg, the perceptions of participants).35 43 This definition highlights the importance of examining how interventions are received as opposed to merely considering how they are intended.43 44 Westhorp argues the usefulness of four additional types of constructs: powers and liabilities (eg, motivation, individual learning, and making agreements and laws), forces (exerting pressure, for example, peer pressure, laws and regulations), interactions (eg, a contract), and feedback and feedforward processes (eg, negotiation).12 These constructs of mechanisms are at work at different levels of (material; psychological/cognitive; social/group and social/institutional) systems.12 Hence, in this study, we consider mechanisms as underlying processes related to multiple contextual levels, that is, the reasoning and responses of individual and groups of stakeholders, as well as to power and resources of societal institutions.

Central to the realist method of inquiry is abductive and retroductive reasoning.45 46 Abductive thinking is a form of inventive and intuitive (‘hunch-driven’) thinking that allows a researcher to creatively imagine, for example, potential mechanisms to be investigated, based on what feels right, logic, what ideas surface based on data or clues.44 47 48 Retroductive thinking involves theorising on and testing of hidden causal mechanisms that have, for example, been imagined through abductive thinking or inductively inferred from descriptions of existing studies.44 46–48 Both types of reasoning are critical and necessary in the iterative process of data collection (for information gleaning) and synthesis (for theory gleaning) in realist studies. Information gleaning is an approach that employs any number of data collection techniques to gather information.48 In the information gleaning process, data sources are explored in order to increase our understanding of the intervention, programme or policy and any underlying mechanisms, for example, how policy dialogues or roadmaps function. Theory gleaning or elicitation is the process of identifying and making explicit the elements of the intervention, actors, mechanisms, outcomes and contexts using the concept of generative causality.49 Both ways of internal reasoning are of instrumental importance in realist research, to elicit and test theories and allow us to move between different levels of abstract and empirical thinking.

The iterative process of data collection and synthesis/analysis

Data collection for this IPT elicitation study involved qualitative methods which were used to theorise on underlying mechanisms of policy dialogues for roadmap development. In the development of this IPT, two main steps can be discerned in which information from different sources was collected:

Information was obtained from a literature review (conducted originally in 2019 and consecutively between 2020 and 2021) on scale-up processes and policy dialogue success factors. We identified relevant international publications and realist studies (information gleaning) by database search (PubMed, Cielo, Google Scholar, Web of Science) and snowballing (originally via the SCUBY Project’s reference list) on frameworks and theories of policy analysis and their application in HICs and LMICs related to health policy dialogue (not specific to integrated chronic care). The information gleaning was followed by theory gleaning, generating two outputs or data syntheses at two different time points, related to scale-up and policy dialogue, respectively. First, the literature review supported the development of different theories of change (ToCs) on the interactive scale-up process. To systematically map the roadmap development and implementation process, two strategic scale-up frameworks in the domain of implementation science50 51 were used to conceptualise the process, which led to different depictions of the cyclical improvement of the roadmap on IC towards scale-up (see online supplemental appendices 3–5). Second, the literature review resulted in insights obtained through abductive and retroductive reasoning into contextual factors, mechanisms and outcomes related to policy dialogues, co-creation and knowledge mobilisation. These insights into non-configured CMOs at multiple levels are displayed in table 1.

Three consecutive research workshops with a multidisciplinary team (including authors MM, EW, JvO and SVB) were organised on the theoretical base for the roadmap (theory gleaning). In a team consisting of two sociologists, three medical doctors, a public health scientist, a political scientist and an anthropologist, we discussed in a series of workshops (held at the Institute of Tropical Medicine and the University of Antwerp, Belgium, in the period between December 2019 and January 2020) the roadmap (intervention) components, taking a ‘theorising’ approach40 to reflect on how, from a participatory governance perspective, the development of a strategy or policy plan (roadmap) and stakeholder engagement (in policy dialogues)—in a complex interplay involving multiple feedback loops—play a role in the scaling up process.

Table 1.

CMOs at multiple levels (based on exploratory literature review)

| Multilayered CMOs | Context (+intervention characteristics, such as evidence use and co-creation) | Mechanisms (what did the intervention, roadmap development in policy dialogue, trigger?) | Outcomes |

| Individual (micro-level) Characteristics of stakeholders, including biological and psychological aspects (ie, improved mental or physical health, improved practice and skills for practitioners)20 72 73 |

|

|

Immediate:

Intermediate:

|

| Groups/networks/interpersonal relations (micro-level) Stakeholder relationships within a system (researcher/practitioner partnerships), practice changes within teams/departments20 72 73 |

|

|

Immediate:

Intermediate:

Long-term:

|

| Organisational or institutional (meso-level) Organisations including rules, norms (culture); capacity-building and organisational structures, funding organisations, educational institutions20 72 73 |

|

|

Immediate:

Intermediate:

Long-term:

|

| Societal or infrastructure (macro-level) Wider social, economic, policy and political impacts; multiple institutions at a national scale; national public engagement, different elements of social and public value such as justice and equality20 72 73 |

Health system building blocks83:

PESTEL factors:

|

|

Intermediate:

Long-term:

|

ICP, Integrated Care Package; MoH, Ministry of Health; NCD, Non-communicable disease.

bmjgh-2023-012637supp004.pdf (273.7KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp003.pdf (315.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp005.pdf (238.5KB, pdf)

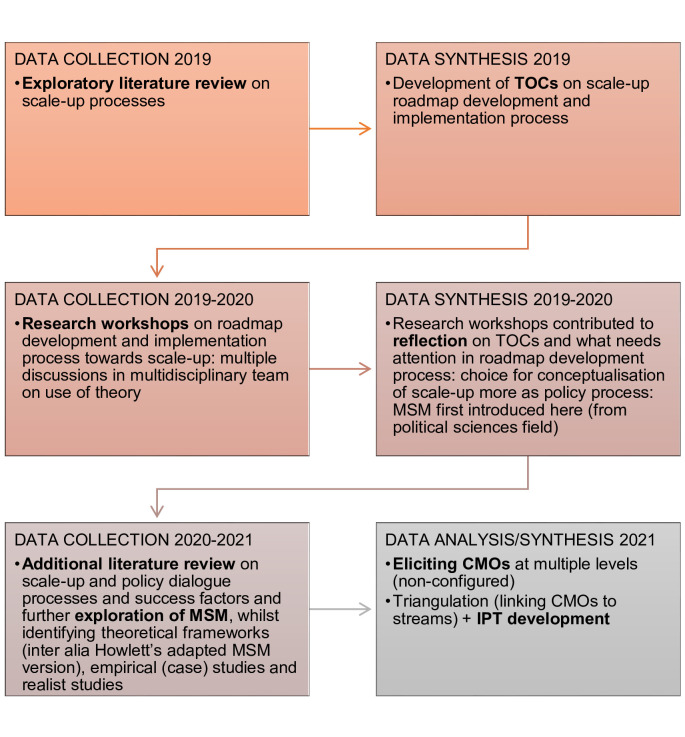

The use of ToCs (as first output of the theory gleaning process, see online supplemental appendices 3–5) in combination with the realist lens (applied in the workshops and CMO thinking in table 1, as second output of the theory gleaning process) provided a cumulative knowledge approach to unveiling the IPT.52 Data were gathered in an iterative research process by exploring theoretical literature and empirical studies,53 using deductive and inductive approaches to identify potential mechanisms (as illustrated in table 1). The iterative approach also emerged by going back and forth between literature and multiple informal discussions in the (wider) research team (with coauthors). Figure 1 showcases a flow chart displaying the iterative process between data collection, synthesis and analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying iterative process of data collection, synthesis and analysis. CMOs, context–mechanism–outcomes; IPT, initial programme theory; MSM, multiple streams model; TOCs, theories of change.

The triangulation of the above-described qualitative methods and tools led to the IPT development. Guided by retroductive theorising, we used the intervention–context–actors–mechanism–outcome (ICAMO) configuration as a realist evaluation heuristic tool to synthesise information into a configurational map, which helps give a visual overview of the retroductive reasoning (by ‘linking’ generative mechanisms). Subsequently, we formulated the IPT in narrative text, using the ‘if…, then…, because…’ statement.54 55 Through this exercise, we identified one overarching programme theory.

While adding explanatory factors, the ICAMO configuration was chosen over the CMO configuration,56 because it particularly acknowledges people’s agency in the design and implementation of interventions—and specifically in this study, in the scale-up process of IC. Following Marchal et al,57 we aim to emphasise the role of actors, recognising the importance of agency and actor engagement, rival actor positions and power dynamics in health policy.57 This focus on actors within ICAMO is particularly warranted when combining policy analysis (theories) and realist approaches.

As a sole exception, table 1 presents unconfigured CMOs and omits the emphasis on ICAMO due to the fact that actors (‘A’) in our project will be context specific and these are derived from literature. In this table, the interventions (‘I’, that is, policy dialogue and scale-up roadmap) are presented within the context (‘C’).

Results

The information and theory gleaning resulted into an IPT based on theories and empirical studies on scale-up and policy dialogue processes. During one of the research workshops that were organised to discuss the roadmap process, format and design, Kingdon’s multiple streams model (MSM)58 59 was proposed in view of its engagement with agency, power, ideology, turbulence and complexity.60 Following further literature review, the MSM adapted by Howlett et al60 61 was deemed appropriate, which reconciles Kingdon and policy process theory,62 facilitating a complexity and public policy perspective63 (via Kingdon) while at the same time following a functional logic (of the policy process/cycle theory) regarding the organic creation of the evidence-based scale-up roadmap toward its policy adoption, implementation, etc.

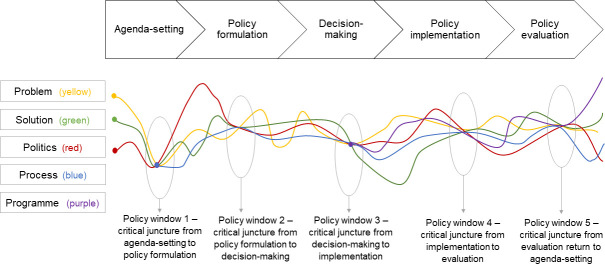

The MSM

The MSM developed by Kingdon58 59 distinguishes three types of processes (streams) that are relevant in agenda setting, namely: problems, policies and politics. In addition to the model’s strength of deciphering decision-making processes in complex environments, studies using Kingdon’s model highlight the importance of timing, expressed with the terms ‘policy windows’ (or missed policy windows).64 Kingdon describes that when these streams collide, they create a ‘window’ of opportunity. In this regard, the model has a specific applicability in more chaotic policy contexts as the role of ‘chance’ or ‘randomness’ is acknowledged in contrast to complexity-reductionist approaches.

Howlett et al note that the MSM approach has its analytical value in understanding policy processes.61 Notwithstanding, they also argue that the streams do not just interact in the agenda-setting stage of the policy cycle (as put forward by Kingdon), but also interact in the policy formulation, decision-making, policy implementation and evaluation stages. For this, they argue, a modification of the model is required. By adding two additional streams, namely process and programmes, the model extends its application beyond the agenda-setting stage to encompass the entire policy cycle. In the convergence of streams, each confluence point brings something new (new actors, new tactics, new resources) joining the flow of the policymaking process.60 61 As proposed by Howlett et al, at the end of the agenda-setting stage and the decision-making stage, the process and programme streams, respectively, erupt from the confluence in a reaction to the policy inputs.61 At this point of convergence or confluence, a policy window or critical juncture is created that drives further/future policy deliberations and establishes the initial conditions of subsequent policy process advances (or retreats).61 Figure 2 displays the multiple streams framework, as proposed and refined by Howlett et al, to include five streams and applied to other dimensions of policymaking set out in the policy cycle model.

Figure 2.

Multiple streams model adapted from Kingdon58 59 and Howlett et al,61 informing the roadmap and dialogue process.

We deemed Howlett et al’s adaptation61 appropriate to guide and inform the co-creative roadmap development and implementation, because the refined ‘five-streams’ model is able to capture the complexity of the (roadmap to) policy process in the context of participation, politics and governance. In IC, multiple actors and interests collide, which is reflected in converging or diverging multilevel efforts, for example, individual healthcare practice versus organisational versus political/system-level activities and commitments. Furthermore, the role of agency is critical within policy processes towards scale-up and present within the MSM. Kingdon argues that ‘pluralist and elite forces’ fight for space in each of these streams of policymaking.64 65 This means that actors are present across these streams but there is also specialisation within streams. For example, politicians are more involved in the politics stream, while academics, researchers and consultants (the ‘elites’) are more involved with policies (or later solutions).59 The problem stream is about public perception of issues, social and mass media.64 65 The process stream involves specific sets of subsystem actors such as bureaucrats, policy analysts and lobby groups organised in advocacy coalitions66 who contribute to deliberations and propose policy alternatives.61 67 And finally, the programme stream brings together resource and implementing organisations,51 financial decision-makers68 and healthcare providers, respectively. All these have been identified as relevant stakeholder groups in the SCUBY implementing countries for the scale-up of IC.

Eliciting the IPT: from MRT to IPT

Particular to this realist study on the IPT development is that the theory (MSM) was explicitly used in the formation of the IPT and in the thinking surrounding the realist configurational heuristic. In other words, this IPT has not yet been empirically tested, but rather builds on the information gleaning on scale-up and policy dialogue processes on the one hand, and theory gleaning and abductive (hunch-based) thinking on the project’s processes, on the other hand. Mechanisms and context conditions were derived from literature and configured to the MSM ‘logic’. Moving from table 1 which presented a wide array of CMOs, table 2 showcases how the adapted MSM helped to focus on relevant mechanisms and context conditions. Table 2 specifically demonstrates the connection between the policy stream, the policy stage and possible mechanisms and/or context conditions that may emerge within or be associated with a particular stream.

Table 2.

Mechanisms and context conditions according to Howlett et al’s MSM

| Stream | Related policy stage | Generative mechanisms and context conditions |

| Problem | Mostly dominant in agenda-setting stage (1) Dominant together with solution stream to assess the implementation of a policy programme in the evaluation stage (5) (‘does the programme tackle the problem?’) |

Problem/stakeholder/organisational/public awareness; common understanding of the needs, problems and values; problem representation |

| Process | Mostly dominant in policy formulation stage (2), next to blending policy problems and solutions creating alternative choice possibilities | Knowledge co-production and co-creation; inclusiveness and participation in the consultation/co-creation process; mutual/organisation learning; procedural and strategic choices (top-down vs bottom-up); transparency; leadership; accountability; urgency; perceived barriers and support; group dynamics; coalition; resources and beliefs; MoH ownership of the process |

| (Policy) solution | Mostly dominant in policy adoption/decision-making stage (3) Dominant together with problem stream to assess the implementation of a policy programme in the evaluation stage (5) (‘does the programme offer an effective solution?’) |

Individual, organisational and system capacities for evidence use (evidence-informed roadmaps and policy dialogues); shared understanding of the needs, values, solutions and policy options between MoH and stakeholders; solution representation and (perceived) effectiveness of alternative policy options |

| Political | Can be dominant or relevant in the main flow of streams at any stage (1–4) | Shared power and interest of political parties/elites; political support, accountability and political commitment (institutional, expressive and financial); politicians’ ideas, ideology and values? |

| Programme | Most dominant in the implementation stage (4) | Programme resources, incentives and learning; perceived barriers and support; community ownership; ideation and motivation of implementers; professional capacity, values and acceptability |

MoH, Ministry of Health; MSM, multiple streams model.

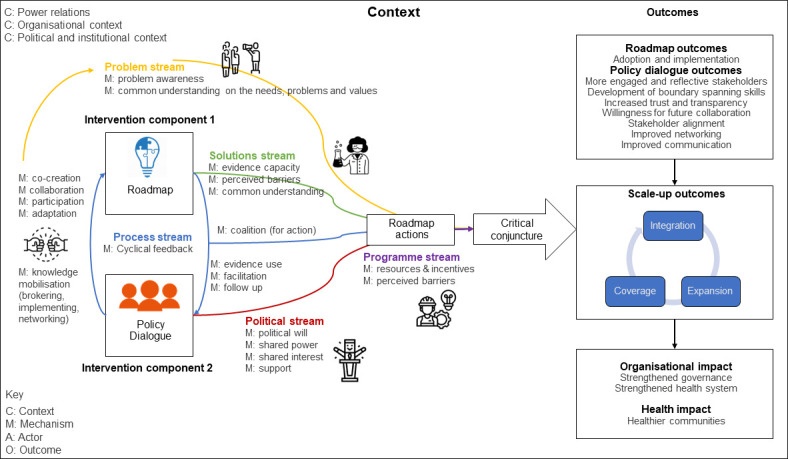

In SCUBY, we hypothesised that synchronisation between ‘the problem’ (public, media and stakeholder awareness), a policy ‘solution’ based on evidence, the ‘political’ side of the problem and solution, the intervention ‘programme’ and contextualised ‘processes’ ensure a higher chance of the success of SCUBY’s interventions (or implementation strategies) and the success of our key implementation instrument—the roadmap. The ICAMO visualisation helped us to conceptualise the ongoing processes and to describe the IPT. The ICAMO configurational mapping is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

An intervention–context–actors–mechanism–outcome representation of the roadmap development and implementation process.

Figure 3 portrays the intervention (I) components (roadmap and policy dialogue), contextual elements (C), the five streams of the MSM—representing groups of actors (A), underlying mechanisms (M) and outcomes (O) on the far-right side of the figure (distinguishing immediate and intermediate roadmap and policy dialogue outcomes, long-term scale-up outcomes, and their organisation and health impact). On the left, the figure shows how there is an interplay between the intervention components, the roadmap and policy dialogue, as depicted via the process stream and how different streams can interact. The streams from Howlett et al’s model harbour the generative (process-related) mechanisms and context conditions and evolve spontaneously within a certain context. There is an emergence in how they get linked to one another and how they influence one another, their co-occurrence. According to the MSM, the streams come together as policy inputs to shape the roadmap actions as policy outputs. For example, problem representations and alternative solutions provide choice possibilities (as inputs) to policymakers, affecting the policy direction chosen—or more specifically the policy formulation—in the scale-up roadmap (as output). Furthermore, the streams are shaped through agency, culture and norms, that is, the structure–agency nexus.69 Following the negotiations of actors (as agents in their respective streams), the confluence point of streams creates a critical juncture opening a policy-generating institutional change. Generally, co-creation means there is a convergence of agency, while the streams theory dictates that success occurs at the convergence of (agency within) different domains: problems, solutions, processes, politics and programmes.

The following underlying theoretical assumptions70 can help clarify the importance of the interaction of streams and the critical role of agency:

We hypothesise that in the context of a policy dialogue, the process (stream) of co-creation (mechanism) can be activated and can be linked to problem awareness or collective sense-making (mechanism) in the problem stream.

Political leaders, consultants and researchers may be part of the policy dialogue and their participation to roadmap creation may trigger evidence sharing, building evidence capacity and political buy-in (mechanisms). This example showcases how the politics and solutions streams may be linked through ‘emergence’.

Lobby groups, community members and activists (from within the problem stream) may also be invited to participate in policy dialogues, which could generate even wider buy-in in the adoption of a scale-up roadmap, yet at the same time can prolong the process of roadmap co-creation, formulation and adoption (decision-making).

Common problems arise in the programme stream (the implementation phase) when other streams diverge. The problem stream diverges, for example, when another problem is perceived as a greater threat (eg, COVID-19) and takes priority (in this case, over integrated chronic care provision). The political stream diverges from the programme stream when political support and associated allocation of funds decline. The solutions stream diverges when alternative solutions demand more attention than the implemented ‘solution’ and the current one becomes ‘outdated’.

Our IPT narrative—and our general hypothesis—building upon the five-streams theory (and the ICAMO configurational mapping) to be examined empirically is the following:

IF: a scale-up roadmap on IC is developed in a co-creative way via policy dialogues that put forward clear goals, are well facilitated, transparent, institutionalised and evidence based.

THEN: it is likely that this emergent and dynamic interplay between policy dialogues and roadmap leads to a critical juncture or policy window for roadmap success and thus roadmap adoption, further implementation and eventually scale-up.

BECAUSE: a co-creative roadmap development process (1) creates a common awareness and understanding on the needs, problems (Problem), values and solutions (Solution); (2) builds evidence-based capacity (Solution); (3) stimulates participation (Process), follow-up (Process) and learning (Process); (4) generates support/buy-in (Political), political commitment (Political) and shared power (Political); and (5) resources and incentives for implementation (Programme).

On examining the three country settings, it is clear that there are strong variations in how the theory will apply. So far, in Belgium, the MSM has been useful in guiding the design and structure of the roadmap and the hypothesised dominant streams (problem, solutions and politics) were aligned with the focus on the agenda-setting stage. Thus, Belgium makes an interesting case on the use of the original Kingdon model to study policy dialogue in the agenda-setting stage, initialising institutional reforms (integration). In Slovenia, MSM has been helpful in identifying the dominant streams within the roadmap process while adopting a phased, stepwise approach from pilot implementation (diversification) to evaluation. Furthermore, Slovenia presents a case of how streams converge, collide or divert within the implementation policy stage. In Cambodia, the streams shed light into key components of the roadmap process, as an evidence-to-policy (knowledge translation) process. Moreover, Cambodia presents an interesting case, putting focus onto the roadmap process from the policy formulation to adoption phase. In a future paper, we will test the IPT in the different country cases, refine and contextualise it.

Discussion

This paper aims to extend the knowledge base on the use of policy dialogues to build a roadmap for scale-up. The IPT describes how (dynamics) and why (theories) the roadmap developed in policy dialogues is expected to work. By testing theories in real cases, the theories can be adapted, refuted and/or reconstructed to elicit a refined theory of how and why a co-created roadmap for scale-up works. Following extensive literature review, discussions and data syntheses, the MSM—an MRT—was used to elicit the IPT. The MSM adapted by Howlett et al60 61 can explore the dynamic processes in policymaking taking place beyond the agenda-setting phase. The realist configurational heuristic representation helped to visualise these co-creative policy processes towards scale-up. Ultimately, co-creation in policy dialogues can support improved health system decision-making practice.30

Reflecting on the role of the roadmap and policy dialogues within the MSM, various conceptualisations are possible. Whereas both are tools, they can both be linked to specific streams (eg, roadmap more synced to the solutions streams, while policy dialogue could be considered as more linked to the politics stream, as presented in figure 3) and yet, they can also act as bridges between streams and actors, bringing ideas and resources together.

In the next phase of the realist evaluation (IPT testing), we aim to explore the use of policy dialogues in different policy cycle phases of the roadmap for scale-up of IC: in Belgium, we focus on the role of the policy dialogue in advancing roadmap actions from agenda-setting to policy formulation and adoption; in Cambodia, we trace the roadmap formulation to policy adoption; and in Slovenia, we explore the use of policy dialogue in the evaluation phase, of roadmap implementation to institutionalisation/maintenance. Hence, policy processes are expected to be very different in the country cases.

Strengths and limitations

In this IPT elicitation study, we aim to discover not whether the interventions work or have impact, but rather focus on how and why the interventions work. Key strengths of this realist study on IPT development include (a) adding to the body of theory on policy dialogue and roadmap process towards scaling up; and (b) providing a lens and approach to look at complex problems in complex contexts (of scaling up, dynamic adaptive health systems and IC).

Related to benefit (a) of strengthening the theory base (theory-building) is the added value of using political science theory, innovatively combining policy analysis and realist approaches. What is novel about the use of the MSM is that this research aims to test (and possibly refine) the MSM by applying a realist generative causation approach. In relation to the strength of enabling the evaluation of complex interventions (b), the realist approach and the MSM are suitable because we have a fluid context (a fragmented vs centralised vs developing health system in the Belgian, Slovenian and Cambodian case, respectively) and fluid intervention design (high plasticity of the intervention,71 completely adapted to the context and stakeholders).

A limitation is that the IPT at this stage remains reasonably descriptive, whereas the ICAMO is not yet fully configured (eg, in table 1 showcasing unconfigured CMOs and the IPT narrative lacking information about context and actors). Another shortcoming in our research is that we did not put more effort in eliciting additional, complementary or rival theories. Our rationale for opting for the MSM adapted by Howlett et al60 61 was: (a) its suitability to explore various contexts where different streams may be dominant and different policy phases are relevant (depending on progress made towards the scale-up of IC), (b) its extended applicability to all policy stages as opposed to the Kingdon model (thereby considering the policy process theory) and finally (c) its integration of other relevant theories in the field of policy analysis. In their 2017 article, Howlett et al incorporated the advocacy coalition framework by Sabatier in the five-streams model.61 In this way, complementary/rival theories have been considered to some extent. It is because of this integration of multiple political science theories that agency has been given a central role, which the adapted MSM is able to illustrate well.

Conclusion

The information and theory gleaning in this study resulted into an IPT based on the political science theory of the MSM adapted by Howlett et al to include five streams which are colliding, converging and diverging across all policy stages. The subsequent steps will be to empirically test the IPT in each of the three country settings (Belgium, Cambodia and Slovenia).

To our knowledge, the MSM has not been previously used to study scale-up processes and has the potential to decipher why (or why not) policy windows for scaling up IC have opened across different settings. Hence, this theoretical study adds to the body of knowledge on policy dialogue (stakeholder collaboration) and the policy process towards scaling up. It can be used for further much-needed theory building on scale-up in HICs as well as LMICs, as it is a domain which remains undertheorised.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the entire SCUBY consortium and specifically the following members for their contributions to the roadmap creation and implementation and valuable inputs and theoretical reflections during various discussions: from the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Antwerp, Belgium: Grace Marie Ku; from the University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium: Roy Remmen, Veerle Buffel and Katrien Danhieux; from the Ljubjana Community Health Centre: Antonija Poplas Susič, Zalika Klemenc Ketiš, Črt Zavrnik, Nataša Stojnić, Matic Mihevc, Tina Virtič and Majda Mori Lukančič; from the National Institute of Public Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Srean Chhim, Savina Chham, Sereyraksmey Long, Sokunthea Yem and Por Ir; and from Julius Global Health, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands: Kerstin Klipstein-Grobusch. Finally, we would like to sincerely thank Ritwik Dahake for his collaboration and meticulous work on editing, proofreading and enhancing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: The first author MM (guarantor) was responsible for the writing of the manuscript, data collection and analysis. MM, JvO, EW and SVB are responsible for the conceptualisation of the work. The second and final author (JvO and SVB) reviewed different versions throughout the drafting process. All authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript, have read the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Funding: This study is part of the ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ (SCUBY) Project, supported by funding from the Horizon 2020 Programme of the European Union (grant number 825432). Sara van Belle is funded by a grant of the Flemish Fund for Scientific Research (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, FWO number 1221821N).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Institutional Review Board (ref. 1323/19) at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium).

References

- 1.Timpel P, Lang C, Wens J, et al. The manage care model - developing an evidence-based and expert-driven chronic care management model for patients with diabetes. Int J Integr Care 2020;20:2. 10.5334/ijic.4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/155002

- 3.Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment . BLOCKS: tools and Methodologies to assess integrated care in Europe. 2017. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/health/publications/blocks-tools-and-methodologies-assess-integrated-care-europe_en

- 4.Borgermans L, Marchal Y, Busetto L, et al. How to improve integrated care for people with chronic conditions: key findings from EU FP-7 project INTEGRATE and beyond. Int J Integr Care 2017;17:7. 10.5334/ijic.3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.University of Oxford, Hughes G. New models of care: the policy discourse of integrated care. PPP 2017;11:72–89. 10.3351/ppp.2017.6792867782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Olmen J, Menon S, Poplas Susič A, et al. Scale-up integrated care for diabetes and hypertension in Cambodia, Slovenia and Belgium (SCUBY): a study design for a quasi-experimental multiple case study. Glob Health Action 2020;13:1824382. 10.1080/16549716.2020.1824382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:132–5. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis CD, Riley BL, Stockton L, et al. Scaling up complex interventions: insights from a realist synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:88. 10.1186/s12961-016-0158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breda J, Wickramasinghe K, Peters DH, et al. One size does not fit all: implementation of interventions for non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019;367:l6434. 10.1136/bmj.l6434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capano G, Pritoni A. Policy cycle. In: Harris P, Bitonti A, Fleisher CS, eds. The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs. New York: Springer International Publishing, 2020. 10.1007/978-3-030-13895-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouffe C. Agonistics: Thinking The World Politically. London, UK: Verso Books, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westhorp G. Chapter 3: understanding mechanisms in realist evaluation and research. In: Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, eds. Doing Realist Research. California, USA: SAGE Publishing, 2018. 10.4135/9781526451729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westhorp G, Prins E, Kusters CSL, et al. Realist evaluation: an overview: Wageningen UR centre for development innovation. 2011. Available: https://edepot.wur.nl/173918

- 14.Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for Scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning 2012;27:365–73. 10.1093/heapol/czr054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangham LJ, Hanson K. Scaling up in international health: what are the key issues Health Policy Plan 2010;25:85–96. 10.1093/heapol/czp066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajan D, Adam T, Husseiny DE. Policy dialogue: What it is and how it can contribute to evidence-informed decision-making. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Available: https://www.uhcpartnership.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2015-Briefing-Note.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bammer G. Key issues in Co-creation with Stakeholders when research problems are complex. Evid Policy 2019;15:423–35. 10.1332/174426419X15532579188099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frow P, McColl-Kennedy JR, Payne A. Co-creation practices: their role in shaping a health care Ecosystem. Indust Market Manag 2016;56:24–39. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voorberg WH, Bekkers V, Tummers LG. A systematic review of Co-creation and Co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag Rev 2015;17:1333–57. 10.1080/14719037.2014.930505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckett K, Farr M, Kothari A, et al. Embracing complexity and uncertainty to create impact: exploring the processes and Transformative potential of Co-produced research through development of a social impact model. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:118. 10.1186/s12961-018-0375-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beran D, Pesantes MA, Berghusen MC, et al. Rethinking research processes to strengthen Co-production in low and middle income countries. BMJ 2021;372:m4785. 10.1136/bmj.m4785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Social Care Institute for Excellence . Co-production in social care: what it is and how to do it - what is Co-production - principles of Co-production. SCIE Guide 51 2013;48:1–20. Available: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/what-is-coproduction/principles-of-coproduction.asp [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorrentino M, Sicilia M, Howlett M. Understanding Co-production as a new public governance tool. Policy and Society 2018;37:277–93. 10.1080/14494035.2018.1521676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nel JL, Roux DJ, Driver A, et al. Knowledge Co-production and boundary work to promote implementation of conservation plans. Conserv Biol 2016;30:176–88. 10.1111/cobi.12560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis LF, Ramírez-Andreotta MD. Participatory research for environmental justice: A critical interpretive synthesis. Environ Health Perspect 2021;129:026001. 10.1289/EHP6274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abelson J, Forest P-G, Eyles J, et al. Deliberations about Deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:239–51. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torfing J, Peters BG, Pierre J, et al. Interactive Governanceadvancing the paradigm. In: Interactive Governance: Advancing the Paradigm. Oxford University Press 2012:1–288, 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199596751.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emerson K. Collaborative governance of public health in Low- and middle-income countries: lessons from research in public administration. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000381. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turk E, Durrance-Bagale A, Han E, et al. International experiences with Co-production and people Centredness offer lessons for COVID-19 responses. BMJ 2021:m4752. 10.1136/bmj.m4752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilson L, Barasa E, Brady L, et al. Collective Sensemaking for action: researchers and decision makers working Collaboratively to strengthen health systems. BMJ 2021;372:m4650. 10.1136/bmj.m4650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gore RJ, Parker R. Analysing power and politics in health policies and systems. Global Public Health 2019;14:481–8. 10.1080/17441692.2019.1575446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redman S, Greenhalgh T, Adedokun L, et al. Co-production of knowledge: the future. BMJ 2021;372:n434. 10.1136/bmj.n434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam T, Hsu J, de Savigny D, et al. Evaluating health systems strengthening interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: are we asking the right questions. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:iv9–19. 10.1093/heapol/czs086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilson L, Raphaely N. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994-2007. Health Policy and Planning 2008;23:294–307. 10.1093/heapol/czn019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation, 2nd edn. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. 2004. Available: https://www.dmeforpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/RE_chapter.pdf

- 37.Chen H-T. Preventing Chronic Disease. Practical Program Evaluation: Assessing and Improving Planning, Implementation, and Effectiveness. California, USA: SAGE Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazi M. Realist evaluation for practice. Br J Social Work 2003;33:803–18. 10.1093/bjsw/33.6.803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith ML. Testable theory development for small-N studies: critical realism and middle-range theory. Int J Inform Tech Syst Approach (IJITSA) 2010;3:41–56. 10.4018/jitsa.2010100203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kislov R, Pope C, Martin GP, et al. Harnessing the power of Theorising in implementation science. Implement Sci 2019;14:103. 10.1186/s13012-019-0957-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, et al. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med 2016;14:96. 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemire S, Kwako A, Nielsen SB, et al. What is this thing called a mechanism? findings from a review of realist evaluations. New Directions for Evaluation 2020;2020:73–86. 10.1002/ev.20428 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/1534875x/2020/167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10 Suppl 1:21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagosh J. Realist synthesis for public health: building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:361–72. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEvoy P, Richards D. Critical realism: a way forward for evaluation research in nursing J Adv Nurs 2003;43:411–20. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukumbang FC, Kabongo EM, Eastwood JG. Examining the application of Retroductive theorizing in realist-informed studies. Int J Qualitat Method 2021;20:160940692110535. 10.1177/16094069211053516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritz B. Comparing abduction and Retroduction in Peircean pragmatism and critical realism. J Crit Realism 2020;19:456–65. 10.1080/14767430.2020.1831817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jagosh J. Retroductive theorizing in Pawson and Tilley’s applied scientific realism. Journal of Critical Realism 2020;19:121–30. 10.1080/14767430.2020.1723301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukumbang FC, Marchal B, Van Belle S, et al. A realist approach to eliciting the initial programme theory of the antiretroviral treatment adherence club intervention in the Western Cape province, South Africa. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:47. 10.1186/s12874-018-0503-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for Scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci 2016;11:12. 10.1186/s13012-016-0374-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization & ExpandNet . Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44432 [Google Scholar]

- 52.M Kabongo E, Mukumbang FC, Delobelle P, et al. Combining the theory of change and realist evaluation approaches to elicit an initial program theory of the Momconnect program in South Africa. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020;20:282. 10.1186/s12874-020-01164-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robert E, Samb OM, Marchal B, et al. Building a middle-range theory of free public Healthcare seeking in sub-Saharan Africa: a realist review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:1002–14. 10.1093/heapol/czx035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westhorp G. Realist impact evaluation: an introduction. 2014. Available: https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/resources/realist-impact-evaluation-introduction

- 55.Leeuw FL. Reconstructing program theories: methods available and problems to be solved. Am J Evaluat 2003;24:5–20. 10.1016/S1098-2140(02)00271-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Weger E, Van Vooren NJE, Wong G, et al. What’s in a realist configuration? deciding which causal configurations to use, how, and why. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2020;19:160940692093857. 10.1177/1609406920938577 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marchal B, Kegels G, Belle S, et al. Chapter 5: theory and realist methods. In: Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, eds. Doing Realist Research. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2018. 10.4135/9781526451729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, 2nd edn. New York: Longman, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howlett M, McConnell A, Perl A. Streams and stages: reconciling Kingdon and policy process theory. Eur J Polit Res 2015;54:419–34. 10.1111/1475-6765.12064 Available: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/ejpr.2015.54.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howlett M, McConnell A, Perl A. Moving policy theory forward: connecting multiple stream and advocacy coalition frameworks to policy cycle models of analysis. Australian J Public Administ 2017;76:65–79. 10.1111/1467-8500.12191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer F, Miller G, Sidney M. Handbook of public policy analysis; 2006Dec21. 10.1201/9781420017007 [DOI]

- 63.Geyer R, Cairney P. Handbook on Complexity and Public Policy. Chelttenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015. 10.4337/9781782549529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rawat P, Morris JC. “Kingdon’s “streams” model at thirty: still relevant in the 21st century” Politics and Policy 2016;44:608–38. 10.1111/polp.12168 Available: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/polp.2016.44.issue-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson SE, Eller WS. Participation in policy streams: testing the separation of problems and solutions in Subnational policy systems. Policy Stud J 2010;38:199–216. 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00358.x Available: http://blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/psj.2010.38.issue-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sabatier PA. Toward better theories of the policy process. APSC 1991;24:147–56. 10.2307/419923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Craft J, Howlett M. Policy advisory systems and evidence-based policy: the location and content of Evidentiary policy advice. In: Young S, ed. Evidence-Based Policy-Making in Canada. Toronto, Canada: University Of Toronto Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campos PA, Reich MR. Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Syst Reform 2019;5:224–35. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giddens A. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, et al. A realist evaluation of community-based Participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015;15:725. 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci 2016;11:141. 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pawson R. The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. In: The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: : SAGE Publications, 2013. 10.4135/9781473913820 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci 2017;12:21. 10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mulvale G, McRae SA, Milicic S. “Teasing apart “the tangled web” of influence of policy dialogues: lessons from a case study of dialogues about Healthcare reform options for Canada”. Implement Sci 2017;12:96. 10.1186/s13012-017-0627-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.May CR, Mair F, Finch T, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci 2009;4:29. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gore RJ, Fox AM, Goldberg AB, et al. Bringing the state back in: understanding and validating measures of governments' political commitment to HIV. Glob Public Health 2014;9:98–120. 10.1080/17441692.2014.881523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davies HTO, Powell AE, Nutley SM. Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: learning from other countries and other sectors – a Multimethod mapping study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2015;3:1–190. 10.3310/hsdr03270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robert E, Rajan D, Koch K, et al. Policy dialogue as a collaborative tool for Multistakeholder health governance: a Scoping study. BMJ Glob Health 2020;4:e002161. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koorts H, Cassar S, Salmon J, et al. Mechanisms of Scaling up: combining a realist perspective and systems analysis to understand successfully scaled interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021;18:42. 10.1186/s12966-021-01103-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.World Health Organization . Concept NOTE: assessment tool for governance for health and well-being. 2018. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/en/about-us/regional-director/regional-directors-emeritus/dr-zsuzsanna-jakab,-2010-2019/health-2020-the-european-policy-for-health-and-well-being/publications/2018/concept-note-assessment-tool-for-governance-for-health-and-well-be

- 82.Robert E, Ridde V, Rajan D, et al. Realist evaluation of the role of the universal health coverage partnership in strengthening policy dialogue for health planning and financing: a protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e022345. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.World Health Organization . Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. 2010. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2023-012637supp001.pdf (443.6KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp002.pdf (224.9KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp004.pdf (273.7KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp003.pdf (315.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012637supp005.pdf (238.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.