Abstract

The coelomycete Colletotrichum gloeosporioides was isolated in pure culture from subcutaneous nodules of the left forearm and elbow of a farmer after traumatic injury. To our knowledge, we report the first case involving this fungus as an etiological agent of subcutaneous infection. The in vitro inhibitory activities of amphotericin B, itraconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, flucytosine, and fluconazole were studied.

Colletotrichum Corda is a complex form genus of the form class Coelomycetes, asexual fungi producing conidia within fruit bodies, named conidiomata. These structures are spherical (pycnidia), with conidiogenous cells lining the inner cavity wall, or are cup-shaped (acervuli), in which case, the conidiogenous cells form a palisade on the surface of the conidiomata. This genus comprises several hundred species, mostly plant pathogens, which have been described mainly on the basis of their conidial morphology and the presence or absence of setae. The genus Colletotrichum was monographed by von Arx (16), and only a restricted number of species was accepted. Although only rarely pathogenic to humans, Colletotrichum spp. have been reported as almost exclusively causing keratitis (6–8, 11, 12), usually after an eye injury. In this report, we describe a diabetic man with a history of trauma who developed a subcutaneous infection caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Sacc.

Case report.

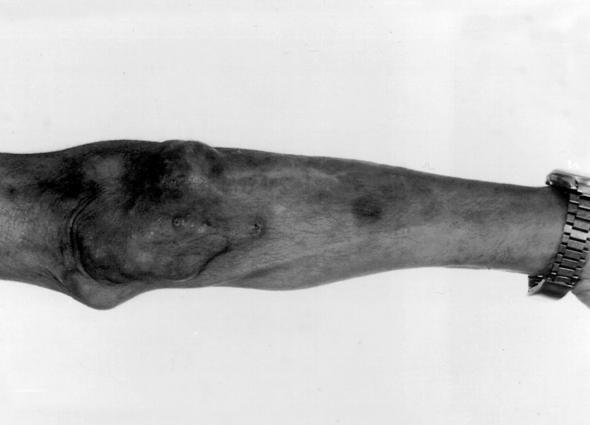

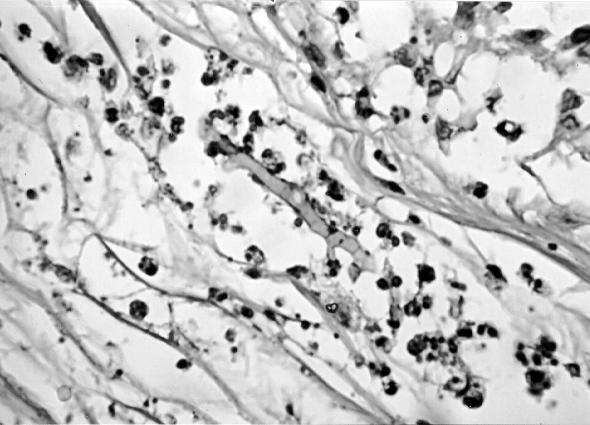

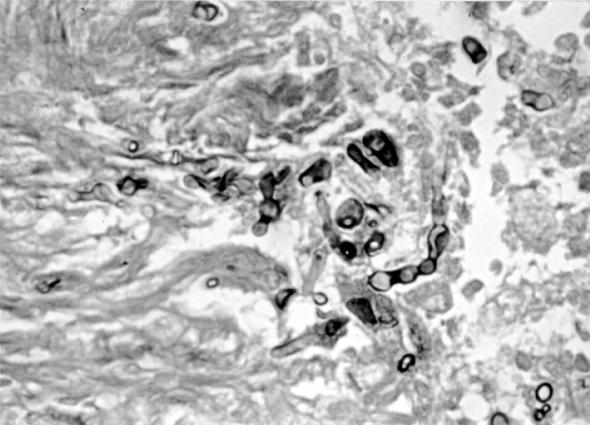

A 56-year-old male farmer and resident of Maringá in the state of Paraná, Brazil, presented himself to the Serviço de Dermatologia do Hospital Universitario Regional de Maringá in May 1996 because of the presence of nodular lesions on his left forearm and elbow. Past medical history revealed that he was diabetic and hypertensive and that he was receiving prednisone (20 mg/day) by autoprescription. He reported a previous traumatic injury of his left hand by rotten wood that had required local suturing. He told of the appearance, approximately 1 year later, of nonpruritic nodules in the same trauma site. He denied having suffered fever and loss of weight. On examination, he presented tuberose-nodular, erythematous, violaceous, solitary or confluent lesions measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter and localized on the left forearm and elbow. In addition, several vinaceous, macular lesions of ca 1.5- cm diameter were observed, also on the dorsum of the forearm (Fig. 1). The results of routine laboratory investigations of blood and urine were within normal limits. Radiography of the thorax showed cardiomegaly with left ventricular hypertrophy and ectasia of the aortic arch. Radiography of the left elbow showed only soft-tissue thickening without evidence of bone or joint lesions. A computerized tomography scan showed the presence of an expansive, hypodense, and multilocular lesion in the soft tissue of the left elbow region. Biopsy of the lesions was performed, and the contents of some of the nodules were aspirated for examination. Direct examination of all specimens sampled revealed the presence of septate, acute angled branching, irregular, hyaline hyphae. A histologic section of the biopsy material stained with periodic acid-Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains showed a hyperplasic epidermis with a psoriasiform pattern. The dermis showed an extensive granulomatous reaction with central necrosis and multiple foci of microabscesses. Throughout the tissue, numerous irregularly shaped, hyaline, septate, branched hyphae were present (Fig. 2 and 3). All of the tissue samples and the contents of the nodules were cultured on Sabouraud’s glucose agar (SGA) and potato dextrose agar (PDA). Fungal colonies grew out in all the cases in both media. Microscopic examination of the cultures demonstrated that all of them presumably belonged to the same species. Routine bacteriological cultures and cultures for mycobacteria were negative. While the diagnostic procedures were being performed, and before establishing treatment, the patient unfortunately died as a result of a car accident. An autopsy was not performed.

FIG. 1.

Nodular lesions over the dorsum of the patient’s left forearm and elbow.

FIG. 2.

Periodic acid-Schiff stain of biopsy specimen from the left elbow showing a segmented branched, hyaline hypha. Magnification, ×440.

FIG. 3.

Methenamine silver stain of the skin biopsy specimen showing toruloid, septate hyphal elements with irregular forms. Magnification, ×440.

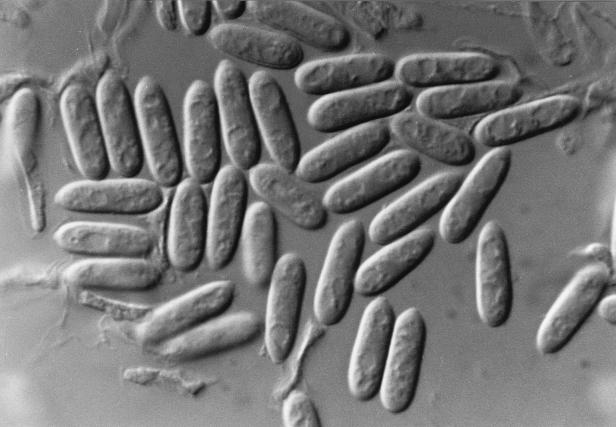

For identification, fungal colonies from the biopsy material and from the nodules’ contents were inoculated into SGA and other routine mycological media, such as PDA, cornmeal, malt extract, and oatmeal agars and incubated at room temperature. All of the media gave rise to white to grayish, loosely textured colonies with similar characteristics. Colonies on PDA grew very quickly, occupying the whole surface of the Petri dish in 10 days. They were greenish gray with pinkish to salmon patches, powdery to velutine, profusely sporulated, and with abundant production of conidiomata; the reverse was grayish (Fig. 4). The colonies on oatmeal agar also grew very quickly. They had a floccose texture with abundant production of white aerial mycelium. The production of conidiomata was mainly restricted to the central areas, and the reverse was uncolored. The conidia were borne on elongated phialides in acervular conidiomata, or, in the early stages of development, on solitary fertile hyphae. The conidia were straight, cylindrical to slightly clavate, hyaline, obtuse at the apex, extremely variable in length, and measured 6 to 26 by 4 to 7 μm (Fig. 5 and 6). Numerous appressoria were also present. They were clavate, triangular or irregular, dark pigmented, and measured 8 to 15 by 5 to 8 μm (Fig. 7). The isolate was identified as C. gloeosporioides. The isolate was subcultured under various conditions and maintained in our mycology laboratory at the Medical School, University Rovira i Virgili, as no. FMR 6273. A living culture of this isolate has been deposited in the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures of The Netherlands.

FIG. 4.

C. gloeosporioides colony growing on PDA after 10 days of incubation.

FIG. 5.

Conidia of C. gloeosporioides. Stain, lactophenol cotton blue. Magnification, ×440.

FIG. 6.

Conidia of C. gloeosporioides. Magnification by Nomarski optics, ×1,440.

FIG. 7.

Appressoria of C. gloeosporioides. Stain, lactophenol cotton blue. Magnification, ×440.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The case isolate and four additional isolates of C. dematium (Pers. ex Fr) Grove, five isolates of C. coccodes (Wallr.) Hughes, and seven isolates of C. gloeosporioides from very diverse sources were tested to determine their susceptibility to antifungal drugs (Table 1). Tests were accomplished by a previously described microdilution method (10) performed mainly according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards’ guidelines for yeasts, by using RPMI 1640 medium (buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS]), an inoculum of 4.4 × 104 to 2.8 × 105 CFU/ml, a temperature of incubation of 30°C, a second-day reading (48 h), and an additive drug dilution procedure.

TABLE 1.

Antifungal susceptibility of Colletotrichum strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) at 48 h/MIC at 72 h (MLC [μg/ml] at 48 h)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | Flucytosine | Fluconazole | Itraconazole | Ketoconazole | Miconazole | |

| C. gloeosporioides | ||||||

| CBS 465.83 | 0.06/0.06 (0.06) | 16/64 (16) | 4/8 (64) | <0.03/0.06 (0.25) | 0.125/0.25 (1) | 4/4 (4) |

| FMR 3383 | 0.06/0.06 (0.06) | 16/64 (16) | 4/8 (64) | 0.06/0.125 (0.25) | 0.125/0.25 (1) | 4/4 (4) |

| FMR 6273 | 0.125/0.25 (4) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | >16/>16 (>16) | 2/4 (>16) | 2/2 (16) |

| CBS 147.28 | 0.125/0.25 (0.5) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | 0.5/0.5 (16) | 2/4 (16) | 2/4 (8) |

| CBS 160.50 | 0.03/0.06 (0.06) | >128/>128 (>128) | 16/16 (>64) | 0.25/0.25 (1) | 0.25/0.5 (2) | 0.25/0.25 (1) |

| CBS 572.97 | 0.06/0.06 (0.06) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | 1/>16 (>16) | 2/4 (16) | 2/2 (16) |

| CBS 953.97 | 0.25/0.25 (0.25) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | 4/>16 (>16) | 4/4 (>16) | 4/4 (4) |

| C. coccodes | ||||||

| IMI 136601 | <0.03/<0.03 (0.25) | >128/>128 (>128) | 32/64 (>64) | 0.5/2 (>16) | 1/2 (>16) | 2/4 (8) |

| CBS 122.25 | 0.06/0.06 (0.25) | >128/>128 (>128) | 8/16 (>64) | 0.06/0.25 (>16) | 0.125/0.25 (>16) | 0.5/0.5 (>16) |

| CBS 125.57 | 4/>16 (>16) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | >16/>16 (>16) | 16/>16 (>16) | 8/>16 (>16) |

| CBS 527.77 | 0.03/0.06 (0.06) | >128/>128 (>128) | 8/16 (>64) | 0.25/0.25 (>16) | 8/16 (>64) | 0.5/0.5 (8) |

| CBS 528.77 | 0.06/0.06 (0.06) | >128/>128 (>128) | 32/65 (>64) | 0.5/0.5 (>16) | 0.5/1 (>16) | 2/2 (8) |

| C. dematium | ||||||

| CBS 167.49 | 0.125/0.125 (0.25) | >128/>128 (>128) | 8/8 (>64) | 0.25/0.25 (8) | 0.25/0.25 (2) | 2/2 (4) |

| CBS 170.59 | 1/1 (1) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | >16/>16 (>16) | 16/16 (>16) | 4/8 (4) |

| CBS 351.73 | 0.06/0.06 (0.125) | 16/34 (>128) | >64/>64 (>64) | >16/>16 (>16) | 8/16 (>16) | 4/4 (>16) |

| CBS 714.95 | 0.5/0.5 (0.5) | >128/>128 (>128) | >64/64 (>64) | >16/>16 (>16) | 16/16 (>16) | 8/8 (8) |

Discussion.

Colletotrichum spp. are typical fungi pathogenic for plants and causing anthracnosis, necrosis, leaf spot, and fruit rot. The diseases caused are commonly seed borne. Some species cause latent infections on woody plants, and the infected plants often show poor growth, and their fruits may rot (17). The species are anamorphs of the genus Glomerella Spauld. & H. Schrenk, classically considered as belonging to the order Phyllachorales, although some evidence exists about their relationship with the Sordariales (15), both orders of the Ascomycota. von Arx (16) delimited the most important species of Colletotrichum, considering their most distinctive characteristics to be the shape and size of the conidia and their specific hosts. However, further studies have enlarged the genus (13). The taxonomy of the genus is still unclear, and a comprehensive review of the numerous species described is needed. Sutton (14) pointed out that in vitro studies are required to determine the nature of the most representative morphological features, such as sclerotia, setae, and appressoria, in order to compare them with those shown in the host plant, because some differences have been reported. C. gloeosporioides is one of the commonest plant-pathogenic fungi to occur in the tropics and subtropics and is found worldwide. It constitutes a very heterogeneous taxon. von Arx (16) has given more than 600 synonyms for this species and has recognized nine forms, but probably many more can be differentiated by a combination of cultural characteristics, morphology, host range, and pathogenicity. Several molecular techniques have been used for a better characterization of the plant-pathogenic strains of this fungus (1, 5). Up to now, four species of Colletotrichum were known to have caused infections in humans or other animals (2). They are C. coccodes, C. dematium, C. gloeosporioides and C. graminicola (Ces.) Wilson. These species had been associated exclusively with keratitis (6–8, 11, 12), but recently Midha et al. (9) described a case of disseminated infection in a neutropenic patient probably caused by an unidentified Colletotrichum sp. Hence, the case of infection reported here is the second one concerning an extraocular infection caused by a member of this genus. This change in the spectrum of the infection has also been noted in other fungi, first associated with keratitis, such as Fusarium (3) and Acremonium (4) spp. among others. The species pathogenic for humans were recently described and illustrated, and a key for their identification was also included (2). The other three pathogenic species can be easily differentiated from C. gloeosporioides by their setose conidiomata. In particular, C. dematium and C. graminicola are clearly distinguished by their falcate conidia, similar to those of Fusarium spp., although unicellular. The ascigerous state of C. gloeosporioides, Glomerella cingulata (Stoneman) Spauld. & H. Schrenk has been reported as developing on PDA (8).

Of the nine previously reported clinical cases of infection attributed to Colletotrichum spp., one was caused by C. dematium (6), one was caused by C. graminicola (11), three were caused by C. coccodes (reported as C. atramentarium) (7), three were caused by C. gloeosporioides (8, 12), and one was caused by a Colletotrichum sp. (9). Only the last one was extraocular; the other eight were typical cases of keratitis. All of these cases followed an ocular injury, except one in which the patient had been treated with general and topical corticosteroid therapy for 3 years because of uveitis (8). The data concerning these cases are very scanty, and the results from the different treatments applied were variable. One patient was successfully treated with topical amphotericin B (6). In another case, the same treatment together with general therapy with flucytosine also resolved the infection (8). However, in a third case, the use of a combination of an amphotericin B suspension and miconazole nitrate eye ointment was ineffective (12). In the invasive case, the patient died despite treatment with amphotericin B and itraconazole (9). In one case, the patient was cured after topical treatment with 4% piramicin (8), and in the most recent case, the patient was also cured after combined treatment with topical natamycin, intracameral amphotericin B, and oral fluconazole (11).

The data obtained from the antifungal susceptibility testing of the isolate from the patient and 15 comparison isolates demonstrated, in general, that the MICs for the organisms were low, with the exception of those of flucytosine and, to a lesser degree, fluconazole. For only one isolate was the MIC of amphotericin B higher than 1 μg/ml. For two isolates, the MICs of miconazole were higher than 4 μg/ml, and for ketoconazole and itraconazole, there were only four isolates, in each case, for which the MICs exceeded such values. Differences between MICs read at 48 h and at 72 h were generally not important. Usually the values were the same after the two readings, and in only one case were the differences higher than 2 dilutions. Examination of the minimal lethal concentrations (MLCs) showed that the majority of isolates displayed a major degree of resistance. They were, however, mainly susceptible to amphotericin B. Only one strain (C. coccodes CBS 125.57) was clearly resistant to all of the drugs tested. No major differences were observed among the MICs and MLCs for the three species tested.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Ajello from Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta, Ga.) for reviewing the manuscript and Luis A. Quiroz and José C. da Silva from the Universidade Estadual de Maringá (Maringá, Brazil) for their kind help in the preparation of this article.

This work was supported by the “Fundació Ciència i Salut” (Reus, Spain).

REFERENCES

- 1.Braithwaite K S, Irwin J A G, Manners J M. Ribosomal DNA as a molecular taxonomic marker for the group species Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Aust Syst Bot. 1990;3:733–738. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Hoog G S, Guarro J, editors. Atlas of clinical fungi. Baarn, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guarro J, Gené J. Opportunistic fusarial infections in humans. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:741–754. doi: 10.1007/BF01690988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, Gené J. Acremonium species, new emerging opportunists: in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1222–1229. doi: 10.1086/516098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He C Z, Masel A M, Irwin J A G, Kelemu S, Manners J A. Distribution and relationship of chromosome-specific dispensable DNA sequences in diverse isolates of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Mycol Res. 1995;99:1325–1333. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao W Q, Shao J Z, Li S Q, Li T Z, Wo S X, Zhang U Z, Chen Q T. Colletotrichum dematium caused keratitis. Chin Med J. 1983;96:391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liesegang T J, Forster R K. Spectrum of microbial keratitis in South Africa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzaki, O., M. Yasuda, and M. Ichinohe. 1988. Keratomycosis due to Glomerella cingulata. Rev. Iber. Micol. 5(Suppl. 1):30.

- 9.Midha N K, Mirzanejad Y, Soni M. Colletrotrichum sp.: plant or human pathogen? Antimicrob Infect Dis Newsl. 1996;15:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pujol I, Guarro J, Llop C, Soler L, Fernández-Ballart J. Comparison study of broth macrodilution and microdilution antifungal susceptibility tests for the filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2106–2110. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritterband D C, Shah M, Seedor J A. Colletotrichum graminicola: a new corneal pathogen. Cornea. 1997;16:362–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla P K, Khan Z A, Lal B, Agrawal P K, Srivastava O P. Clinical and experimental keratitis caused by Colletotrichum state of Glomerella cingulata and Acrophialophora fusispora. Sabouraudia. 1983;21:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton B C. Colletotrichum dematium (Pers. ex Fr.) Grove and C. trichellum (Fr. ex. Fr.) Duke. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1962;45:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton B C. The Coelomycetes. Kew, United Kingdom: Commonwealth Mycological Institute; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uecker F A. Ontogeny of the ascoma of Glomerella cingulata. Mycologia. 1994;86:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Arx J A. Die Arten der Gattung Colletotrichum. Phytopathol Z. 1957;29:413–468. [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Arx J A. Plant pathogenic fungi. Beih Nova Hedwigia. 1987;87:1–288. [Google Scholar]