Key Points

Question

What were the treatment patterns for alopecia areata (AA) in adults in the US from 2015 to 2020?

Findings

In this cohort study of 45 483 adults with AA, on the basis of US medical and pharmacy claims data, most common treatments for AA included intralesional, topical, intramuscular, and oral corticosteroids. Initially, half of patients were not receiving treatment, and almost three-quarters of patients were not receiving treatment at 12 months.

Meaning

These findings indicate that corticosteroids are the main treatment used for AA in adults, with most patients not receiving active treatment 1 year after diagnosis; further studies are needed to understand this absence of treatment.

This cohort study evaluates treatment patterns for adults with alopecia areata in the US between 2015 and 2020.

Abstract

Importance

Alopecia areata (AA) is characterized by hair loss ranging from patches of hair loss to more extensive forms, including alopecia totalis (AT) and alopecia universalis (AU). There is a lack of consensus for treatment. Understanding current practice patterns could help the identification of treatment needs and development of standards of care.

Objective

To review treatment patterns for adults with AA in the US between 2015 and 2020.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used medicine and pharmacy claims for commercially insured individuals from the IBM MarketScan Research Database to assess adults (≥18 years) newly treated for AA between October 15, 2015, and February 28, 2020. Alopecia areata was identified based on having at least 1 diagnosis of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision code L63.x. Patients were required to have at least 365 days of continuous health plan enrollment before and after the cohort entry date. Patients were required to be free of AA diagnosis codes 365 days before the cohort entry date. Statistical analyses were conducted between 2019 and 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Main outcomes were treatment patterns for all patients with AA and subgroups of (1) patients with AT or AU and (2) those cared for by a dermatologist on the cohort entry date. Longitudinal therapy course during the first year after the diagnosis was also examined.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 45 483 individuals (mean [SD] age, 43.8 [14.2] years; 29 903 [65.7%] female). During the year of follow-up, 30 217 patients (66.4%) received at least 1 AA treatment. The most common treatments were intralesional (19 014 [41.8%]), topical (18 604 [40.9%]), intramuscular (17 328 [38.1%]), and oral (9378 [20.6%]) corticosteroids. Compared with patients without AT or AU, patients with AT or AU a lower frequency of intralesional steroid (359 [11.1%] vs 18 655 [44.1%], P < .001) and higher frequency of topical corticosteroid (817 [25.4%] vs 17 787 [42.1%], P < .001) use. Almost half of patients (21 489 [47.2%]) received no treatment on the day of diagnosis. By 12 months, 32 659 (71.8%) were not receiving any treatment, making no treatment the largest study group.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large cohort study of commercially insured individuals, corticosteroids were the most commonly used treatment for adults with AA between 2015 and 2020. At 365 days after diagnosis, more than two-thirds of patients were no longer receiving any AA treatment. Further studies are needed to understand the reasons for the absence of treatment.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease of hair loss with a lifetime prevalence of 2.1%.1 Current treatment options for AA have varying efficacy and tolerability. Although practice guidelines have been published,2,3,4 data on treatments that patients receive in routine care settings are limited.5,6,7,8,9 An understanding of practice patterns can help in identifying treatment needs and developing the standards of care.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a large US health care database, IBM MarketScan Research Database, which contains longitudinal medical and pharmacy claims for 210 million commercially insured individuals in the US.10 All data were deidentified according to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and the study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Design and Population

We identified adults (aged ≥18 years) who were newly diagnosed with AA between October 15, 2015, and February 28, 2020. Race and ethnicity data are not available in the MarketScan database and thus could not be collected. Alopecia areata was identified based on having at least 1 diagnosis of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L63.x.11 The cohort entry date for each patient was defined as the date of the first eligible AA code. Patients were required to have a minimum of 365 days of continuous health plan enrollment before and after their cohort entry date. To identify newly diagnosed AA cases, we required a washout period of 365 days before the cohort entry. In addition, we required 365 days of continuous enrollment after the cohort entry to assess their treatment characteristics for 1 year without accounting for censoring.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted between 2019 and 2023. We measured baseline variables potentially related to AA and its treatment patterns during the 365 days before and including the cohort entry date. We then assessed the frequencies of predefined AA treatments (eTable 1 in Supplement 1) identifiable in insurance claims during the first year. Baseline characteristics and treatment patterns were assessed for the primary cohort and subgroups classified by (1) the extent of alopecia (alopecia totalis [AT] or alopecia universalis [AU] vs no AT or AU) and (2) involvement of a dermatologist (based on a practitioner code of 215 or 545) on the cohort entry date. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated between the subgroups, and variables with an SMD greater than 0.1 were adjusted for in a multivariate regression of treatment pattern comparisons.12

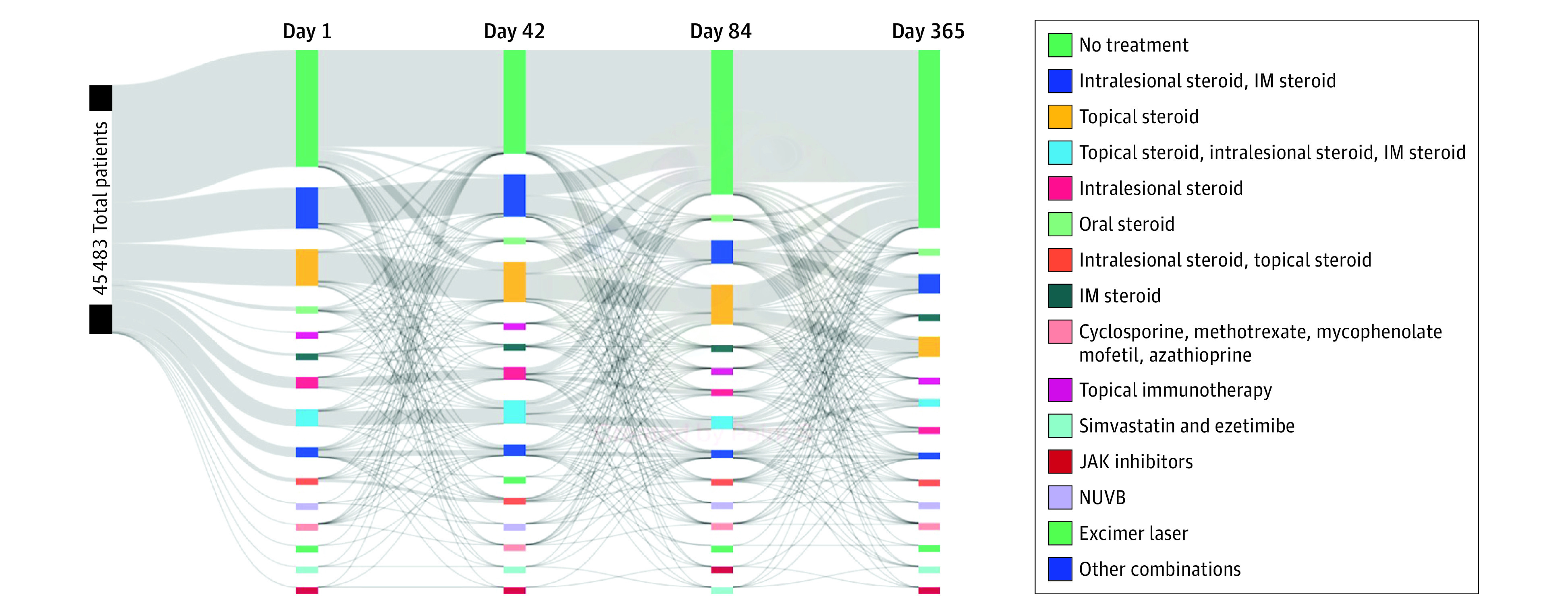

To evaluate longitudinal treatment patterns, we created a Sankey plot to visualize patterns of treatment change at days 1, 42, 84, and 365. Days 42 and 84 were selected to capture the typical treatment intervals of 4 to 6 weeks during the initial phases of AA management. We accounted for each treatment’s duration and allowed a grace period of 30 days for treatment discontinuation (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Analyses were conducted using Aetion Evidence Platform Software, version 2020 for real-world data analysis (Aetion Inc).13

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Our cohort consisted of 45 483 individuals with AA (mean [SD] age, 43.8 [14.2] years; 29 903 [65.7%] female and 15 580 [34.3%]) (Table 1; eFigure in Supplement 1). Patients with AT or AU were older than patients without AT or AU (mean [SD] age, 46.6 [14.8] vs 43.6 [14.2] years; SMD, 0.4). A total of 18 868 patients (41.5%) were seen by a nondermatologist health care professional on the date of their cohort entry.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Primary Alopecia Areata Cohort and Subgroupsa.

| Characteristic | Primary cohort (N = 45 483) | Extent of disease | Dermatologist involvement on diagnosis date | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With AT or AU (n = 3221) | Without AT or AU (n = 42 262) | SMD | Yes (n = 26 615) | No (n = 18 868) | SMD | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.8 (14.2) | 46.6 (14.8) | 43.6 (14.2) | 0.40 | 43.8 (14.1) | 43.7 (14.4) | 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 29 903 (65.7) | 2387 (74.1) | 27 516 (65.1) | 0.18 | 16 922 (63.6) | 12 981 (68.8) | 0.11 |

| Maleb | 15 580 (34.3) | 834 (25.9) | 14 746 (34.9) | NA | 9693 (36.4) | 5881 (31.2) | NA |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 11 921 (26.2) | 856 (26.6) | 11 065 (26.2) | 0.01 | 7663 (28.8) | 4258 (22.6) | 0.14 |

| North Central | 7844 (17.2) | 488 (15.2) | 7356 (17.4) | 0.06 | 4496 (16.9) | 3348 (17.7) | 0.02 |

| South | 18 826 (41.4) | 1457 (45.2) | 17 369 (41.1) | 0.08 | 11 255 (42.3) | 7571 (40.1) | 0.04 |

| West | 6812 (15.0) | 418 (13.0) | 6394 (15.1) | 0.06 | 3182 (12.0) | 3630 (19.2) | 0.20 |

| Unknown | 80 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 78 (0.2) | 0.03 | 19 (0.1) | 61 (0.3) | 0.04 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Atopic dermatitis | 1714 (3.8) | 118 (3.7) | 1596 (3.8) | 0.01 | 1223 (4.6) | 491 (2.6) | 0.11 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 5733 (12.6) | 486 (15.1) | 5247 (12.4) | 0.08 | 3305 (12.4) | 2428 (12.9) | 0.02 |

| Asthma | 3236 (7.1) | 248 (7.7) | 2988 (7.1) | 0.02 | 1896 (7.1) | 1340 (7.1) | <0.01 |

| Thyroid disease | 6759 (14.9) | 670 (20.8) | 6089 (14.4) | 0.02 | 3668 (13.8) | 3091 (16.4) | 0.07 |

| Major depressive disorder | 3686 (8.1) | 293 (9.1) | 3393 (8.0) | 0.04 | 1947 (7.3) | 1739 (9.2) | 0.07 |

| Bipolar or manic disorder | 428 (0.9) | 43 (1.3) | 385 (0.9) | 0.04 | 219 (0.8) | 209 (1.1) | 0.03 |

| Anxiety disorder, including OCD | 6136 (13.5) | 496 (15.4) | 5640 (13.3) | 0.06 | 3285 (12.3) | 2851 (15.1) | 0.08 |

| Schizophrenia | 31 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 29 (0.1) | <0.01 | 17 (0.1) | 14 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| CCI score, mean (SD) | 0.72 (1.25) | 0.96 (1.53) | 0.70 (1.22) | 0.03 | 0.68 (1.17) | 0.78 (1.35) | 0.01 |

| Medication use | |||||||

| Statin | 5865 (12.9) | 531 (16.5) | 5334 (12.6) | 0.11 | 3425 (12.9) | 2440 (12.9) | <0.01 |

| Ezetimibe-simvastatin | 90 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | 81 (0.2) | 0.02 | 63 (0.2) | 27 (0.1) | 0.03 |

| High-intensity statin | 1290 (2.8) | 83 (2.6) | 1207 (2.9) | 0.02 | 719 (2.7) | 571 (3.0) | 0.02 |

| Health care use | |||||||

| ED visit | 613 (1.3) | 66 (2.0) | 547 (1.3) | 0.05 | 291 (1.1) | 322 (1.7) | 0.05 |

| Hospitalization | 2339 (5.1) | 253 (7.9) | 2086 (4.9) | 0.12 | 1125 (4.2) | 1214 (6.4) | 0.10 |

| No. of unique medications prescribed, mean (SD) | 13.1 (17.5) | 15.7 (19.3) | 12.9 (17.3) | 0.37 | 12.9 (16.8) | 13.3 (18.4) | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; CCI, Combined Comorbidity Index; ED, emergency department; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Data are presented in number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

SMD for male patients was not calculated because gender was treated as a binary variable and female sex was adjusted for in the multivariate model already.

Overall Treatment Received

During the follow-up, 30 217 patients (66.4%) in the primary cohort received at least 1 AA treatment at 1 or more time points. Intralesional injection of a corticosteroid was the most common treatment (19 014 [41.8%]), followed by topical (18 604 [40.9%]), intramuscular (17 328 [38.1%]), and oral (9378 [20.6%]) steroids (Table 2). Only a few patients were treated with other systemic therapy, including Janus kinase inhibitors, diphenylcyclopropenone, and phototherapy.

Table 2. Treatment Frequencies During the First 365 Days After Cohort Entry in the Primary Alopecia Area Cohort and Subgroupsa.

| Treatment type | Primary cohort (N = 45 483) | Extent of disease | Dermatologist involvement on diagnosis date | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With AT or AU (n = 3221) | Without AT or AU (n = 42 262) | P value | Dermatologist visit on CED (n = 26 615) | Nondermatologist visit on CED (n = 18 868) | P value | ||

| ILI total | 19 014 (41.8) | 359 (11.1) | 18 655 (44.1) | <.001 | 14 298 (53.7) | 4716 (25.0) | <.001 |

| ILI <7 times | 15 153 (33.3) | 253 (7.9) | 14 900 (35.3) | <.001 | 11 214 (42.1) | 3939 (20.9) | <.001 |

| ILI >7 times | 7466 (16.4) | 182 (5.7) | 7284 (17.2) | <.001 | 5834 (21.9) | 1632 (8.6) | .04 |

| Topical steroid | 18 604 (40.9) | 817 (25.4) | 17 787 (42.1) | <.001 | 12 266 (46.1) | 6338 (33.6) | <.001 |

| Intramuscular steroid | 17 328 (38.1) | 436 (13.5) | 16 892 (40.0) | <.001 | 12 788 (48.0) | 4540 (24.1) | <.001 |

| Oral steroid | 9378 (20.6) | 742 (23.0) | 8636 (20.4) | .20 | 5514 (20.7) | 3864 (20.5) | .66 |

| Supply, mean (SD), d | 22.3 (47.6) | 24.6 (52.9) | 22.1 (47.1) | .80 | 22.3 (47.1) | 22.3 (48.2) | .74 |

| Cumulative dose, mean (SD), mg | 395.7 (699.8) | 453.9 (858.4) | 390.7 (684.3) | .09 | 389.9 (639.0) | 403.8 (778.4) | .39 |

| Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus | 1505 (3.3) | 69 (2.1) | 1436 (3.4) | <.001 | 1096 (4.1) | 409 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine | 1207 (2.7) | 122 (3.8) | 1085 (2.6) | .02 | 719 (2.7) | 488 (2.6) | .22 |

| Oral JAK inhibitors | 101 (0.2) | 20 (0.6) | 81 (0.2) | <.001 | 67 (0.3) | 34 (0.2) | .13 |

| Simvastatin and ezetimibe | 148 (0.3) | 13 (0.4) | 135 (0.3) | .73 | 107 (0.4) | 41 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Diphenylcyclopropenone | 728 (1.6) | 54 (1.7) | 674 (1.6) | .80 | 444 (1.7) | 284 (1.5) | .30 |

| Narrowband UV-B | 151 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 145 (0.3) | .11 | 114 (0.4) | 37 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Excimer laser | 73 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 71 (0.2) | .12 | 62 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; CED, cohort entry date; ILI, intralesional injection; JAK, Janus kinase.

Data were calculated only among the treated. Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated. P values were calculated based on multivariate logistic or linear regression, adjusted for baseline characteristics with a standardized mean difference greater than 0.1 in Table 1. The CED is defined as the date of the first eligible alopecia areata code.

In the subgroups, the AT or AU group had a lower frequency of intralesional injections (359 [11.1%] vs 18 655 [44.1%]; P < .001) and topical steroid treatment (817 [25.4%] vs 17 787 [42.1%]; P < .001) compared with the group without AT or AU. There was no significant difference in the mean cumulative prednisone equivalent dose between the groups with vs without AT or AU (454 vs 391 mg; P = .09). The group that was initially seen by a dermatologist had a higher frequency of intralesional injections (14 298 [53.7%] vs 4716 [25.0%]; P < .001) and topical steroid treatment (12 266 [46.1%] vs 6338 [33.6%]; P < .001); frequency of oral steroid prescription was not statistically different (5514 [20.7%] vs 3864 [20.5%]; P = .66).

Longitudinal Treatment Patterns

Almost half (21 489 [47.2%]) of patients received no treatment on the date of their AA diagnosis (Figure). Of these untreated patients on this date (day 1), 17 865 (83.1%) had not received any treatment by day 42. When treatment was initiated, topical steroids (1546 [7.2%]) and intralesional and intramuscular steroid combination (665 [3.1%]) were most commonly used.

Figure. Sankey Plot Illustrating a Longitudinal Pattern of Care in Patients With Alopecia Areata During Their First Year of Treatment.

Four time points (1, 42, 84, and 365 days after cohort entry) were selected to visualize the longitudinal trend of treatment. IM indicates intramuscular; JAK, Janus kinase; and NUVB, narrowband UV-B.

Intralesional and intramuscular steroid combination was the second most common treatment option for AA on day 1 (7585 [16.7%]), with 6534 (86.1%) of these patients continuing with the same treatment on day 42. However, reflecting diverse treatment trajectories among patients with AA, only 3500 patients (7.7%) were still receiving intralesional-intramuscular steroid on day 365. On day 365, 32 659 (71.8%) of the entire cohort were not receiving any treatment, marking no treatment as the most common treatment management at the end of the follow-up.

Discussion

This cohort study provides a summary of treatment patterns for adults with AA during their first year of diagnosis in a US routine clinical setting between 2015 and 2020. We used data from the MarketScan database similar to a recently published analysis describing the epidemiology of AA among children and adults14 and found that although two-thirds of patients received some form of treatment during the first year after diagnosis, intralesional steroids were the most used treatment for AA in adults.7,9 Other nonsteroid treatments were infrequently used. More than 70% were not receiving active treatment 12 months after diagnosis.

The absence of treatment at day 365 for most patients has multiple potential explanations. In some patients, AA resolves spontaneously.8 Alternatively, some may find the adverse effects of the treatments themselves to be unpalatable, especially in the context of limited efficacy.6,8 Furthermore, our predefined grace period of 30 days after the end of a treatment may not fully capture patients who seek care infrequently. Future longitudinal studies are needed to understand why the number of patients receiving no treatment is substantial after 1 year of follow-up and how the disease severity and treatment trajectories could differ between patients who had initial visits with dermatologists and those who did not. Our reported treatment trends may change as newer treatments emerge, including JAK inhibitors and other novel treatments.

Limitations

Our results must be interpreted in the context of limitations of our study design. Because our analyses were based on insurance claims data, we could not capture over-the-counter medications or treatments potentially not entered through the claims database. Moreover, our study is subject to outcome misclassification because the definition of a single ICD-10 code for defining AA and its subsets has not been validated using US claims data. Our requirement of continuous insurance eligibility before and after the cohort entry also limits generalizability. In addition, the medications we evaluated may have been prescribed for other indications, and the days of supply assigned for nonoral agents, such as topical steroids or intralesional steroids, may not accurately reflect the patient’s treatment trajectory if they were not routinely used.

Conclusions

This large cohort study of adult patients with AA in the US describes treatment patterns of these patients during the first year after diagnosis. The most common treatments in this cohort were intralesional or topical corticosteroids, and there was a dynamic change in treatment over the course of a year, culminating with no prescription therapy for most patients. Additional studies are needed to understand the reasons for treatment absence after 1 year of follow-up.

eTable 1. Classification of Alopecia Areata Treatments Utilized in Insurance Claims Analyses

eTable 2. Assigned Days of Supply for Treatment Groups Specified in Sankey Plot

eFigure. Flowchart of the Study Population Selection

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, Torgerson RR. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1% by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990-2009. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(4):1141-1142. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi A, Muscianese M, Piraccini BM, et al. Italian Guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of alopecia areata. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019;154(6):609-623. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.19.06458-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cranwell WC, Lai VW, Photiou L, et al. Treatment of alopecia areata: an Australian expert consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(2):163-170. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meah N, Wall D, York K, et al. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(1):123-130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farhangian ME, McMichael AJ, Huang KE, Feldman SR. Treatment of alopecia areata in the United States: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(9):1012-1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, Brown JR, Joyce C, Huang KP. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: a U.S. survey. Int J Trichology. 2017;9(4):160-164. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_53_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senna M, Ko J, Tosti A, et al. Alopecia areata treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and comorbidities in the US population using insurance claims. Adv Ther. 2021;38(9):4646-4658. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01845-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Lee WS. Management of alopecia areata: updates and algorithmic approach. J Dermatol. 2017;44(11):1199-1211. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostaghimi A, Gandhi K, Done N, et al. All-cause health care resource utilization and costs among adults with alopecia areata: a retrospective claims database study in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(4):426-434. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.4.426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen L. IBM MarketScan Research Databases for life sciences researchers. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/0NKLE57Y

- 11.Lavian J, Li SJ, Lee EY, et al. Validation of case identification for alopecia areata using international classification of diseases coding. Int J Trichology. 2020;12(5):234-237. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_67_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. P T. 2008;33(12):700-711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SV, Verpillat P, Rassen JA, Patrick A, Garry EM, Bartels DB. Transparency and reproducibility of observational cohort studies using large healthcare databases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(3):325-332. doi: 10.1002/cpt.329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(4):411-418. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Classification of Alopecia Areata Treatments Utilized in Insurance Claims Analyses

eTable 2. Assigned Days of Supply for Treatment Groups Specified in Sankey Plot

eFigure. Flowchart of the Study Population Selection

Data Sharing Statement