Abstract

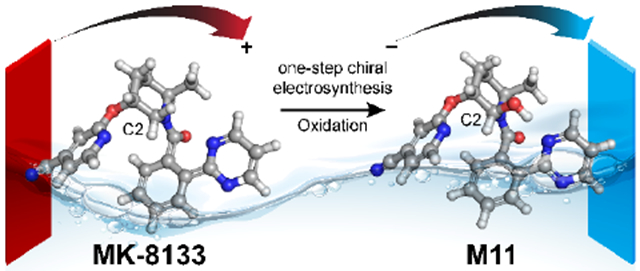

Synthesis of drug metabolites, which often have complex structures, is an integral step in the evaluation of drug candidate metabolism, pharmacokinetic properties, and safety profiles. Frequently, such synthetic endeavors entail arduous, multiple-step de novo synthetic routes. Herein we present the one-step Shono-type electrochemical synthesis of milligrams of chiral α-hydroxyl amide metabolites of two orexin receptor antagonists, MK-8133 and MK-6096, as revealed by a small-scale (pico- to nano-mole level) reaction screening using a lab-built online electrochemistry/mass spectrometry (EC/MS) platform. The electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133 and MK-6096 was conducted in aqueous media and found to produce the corresponding α-piperidinols with exclusive regio- and stereoselectivity, as confirmed by high resolution NMR characterization of products. Based on DFT calculations, the exceptional regio- and stereoselectivity for this electrochemical oxidation are governed by more favorable energetics of the transition state leading to the preferred secondary carbon radical α to the amide group and subsequent steric hindrance associated with the U-shaped conformation of the cation derived from the secondary α-carbon radical, respectively.

Keywords: electrochemical synthesis, chiral synthesis, drug metabolites, mass spectrometry, NMR characterization, DFT

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Insomnia is a common disorder affecting 10–15% of the population and is often associated with other physical and psychological problems.1 Following the discovery of orexin, the novel therapies of dual OX1R and OX2R orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) and selective orexin receptor antagonists (SORAs) have advanced into late stage clinical development. Examples of such therapies are MK-8133 and MK-6096 (see Scheme 1).2-7 These drugs incorporate a piperidine core in their structures. Piperidine moieties are an integral feature of many alkaloid structures and drug development studies have led to the preparation of many highly efficient drugs containing substituted piperidine and piperazine structural moieties.2 During a preclinical safety study, a major circulating metabolite M11 from MK-8133 (Scheme 1) was detected, isolated from pooled rat plasma, and characterized by mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. Metabolic studies are an integral component of drug candidate pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety profiling in the drug development process.3-7 To further understand biological activity of the M11 metabolite, in addition to the potential for interaction with other drugs, milligram quantities of the metabolite were needed. Historically, the required milligram quantities of metabolites for testing was fulfilled using classical organic synthetic procedures, which can be a demanding and lengthy process, necessitating a significant and continuing resource commitment.8, 9 Due to the structural complexity of the MK-8133, coupled with enantiomeric purity requirements, it was estimated that at a minimum, a four-step linear synthesis (e.g., the synthesis of metabolite of suvorexant required a four-step linear synthesis10) would be needed to provide the requisite quantities of the M11 metabolite.

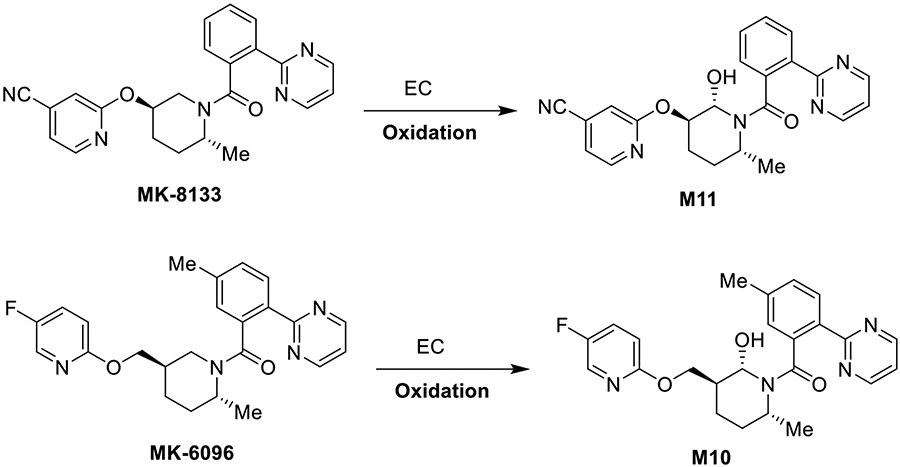

Scheme 1.

One-step electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133 and MK-6096 to produce hydroxylated metabolites, M11 and M10, respectively.

Electrochemical synthetic procedures afford a powerful and convenient method for the oxidative modification of complex organic molecules and have garnered considerable interest.11-24 Much milder oxidants and reductants can be employed in electrochemical redox reactions, with protons from water serving as the oxidant in many cases, and toxic transition metal catalysts can often be avoided entirely. Electrochemical reactions produce little to no waste and comply with the tenets of “green chemistry.”25 In addition, electrochemical redox reactions occur at ambient temperature and pressure, avoiding the inherent sensitivity issues associated with many synthetic organic transformations.25 In concert, these attributes make electrochemical synthesis highly attractive and numerous remarkable transformations via electrochemical reactions have been reported.26-35 For instance, Shono oxidations36-38 are among the most widely employed electrochemical methods for the functionalization of C-H bonds adjacent to nitrogen atoms. In Shono oxidation, amides or carbamates in alcohol solvents are electrochemically oxidized to give the corresponding N- or O-acetals. However, such oxidations simultaneously affording both regio- and stereoselective electrochemical synthesis have not been reported. We reasoned that M11 could be prepared from its parent molecule MK-8133 via direct Shono-type electro-oxidation, considering that MK-8133 has an amide core structure.

The combination of electrochemistry (EC) with mass spectrometry (MS), EC/MS, can be versatile, for mimicking drug metabolism, cleaving proteins/peptides, reducing protein disulfide bonds, facilitating protein/peptide quantitation, and determining the location of unsaturated double bonds in lipids.39-44 The method can also be used to observe elusive reaction intermediates45-54 and for electrosynthetic reaction screening.55-57 Significant progress has been made recently in the application of EC/MS to mimic drug metabolism, especially in the case of oxidative metabolites whose formation is catalyzed by cytochrome P450.58-61 For example, reactions such as aliphatic or aromatic hydroxylation, N-dealkylation or epoxidation can be mimicked using an online EC/MS platform.62-68

In this study, we describe a clean, one-step Shono-type electrochemical synthesis of the α-piperidinol amide metabolites of MK-8133 and MK-6096 (Scheme 1), which otherwise would involve a multiple step de novo synthesis. Optimal conditions for the desired metabolite formation were determined via screening using online EC/MS using minimal amounts of substrates (pico- to nano-mole level). Once established, the optimal conditions were employed with a large electrochemical cell to prepare milligram quantities of the hydroxylated metabolites. Strikingly, the oxidation was observed to be exclusively regio- and stereoselective as determined by high resolution NMR. Although the electrolytic yield varied from a moderate 40-50% for small scale electrolysis in thin-layer electrochemical flow cell to as low as 14-17% for larger scale electrolysis in the SynthesisCell™; nevertheless, milligram quantities of desired metabolites (M11 and M10, respectively, Scheme 1) were successfully obtained in this one-step electrochemical procedure. Following the characterization of the metabolite structures and the confirmation of the stereochemical orientation of electrochemically introduced 2-hydroxyl substituent, computational work was next undertaken to better understand the unique regio- and stereoselectivity observed for the oxidation of MK-8133 and MK-6096.

Results and Discussion

Direct electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133

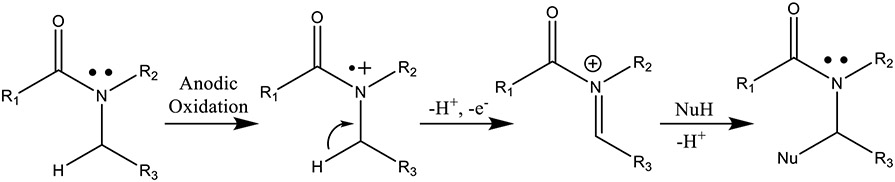

Electrochemistry has been increasingly employed in recent years to mimic oxidative metabolism typically encountered during phase I clinical trials of drug candidates, especially those oxidations catalyzed by cytochrome P450.69-72 Anodic oxidation of amides can generate N-acyliminum ions, which can subsequently undergo elimination, or conversely, these ions can be “trapped” by nucleophiles, functionalizing the α-position of the amide.73-75 Analogously, if the anodic oxidation is conducted in aqueous media, it is possible to form the α-hydroxyl amide product (Nu=OH−, Scheme 2). In this study, we envisioned that electrochemistry might be a highly attractive alternative to synthesize the desired α-hydroxyl metabolites like M11 and M10.

Scheme 2.

Schematic representation of the anodic electrochemical oxidation of an amide where NuH = nucleophile; e.g., water in this study.

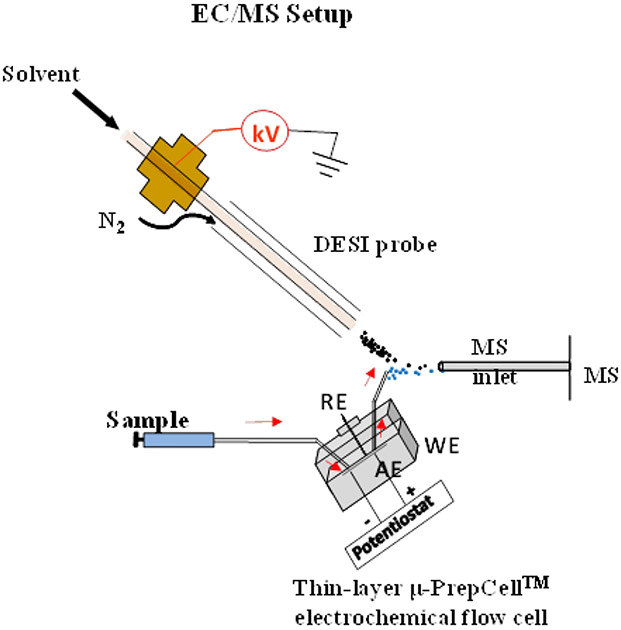

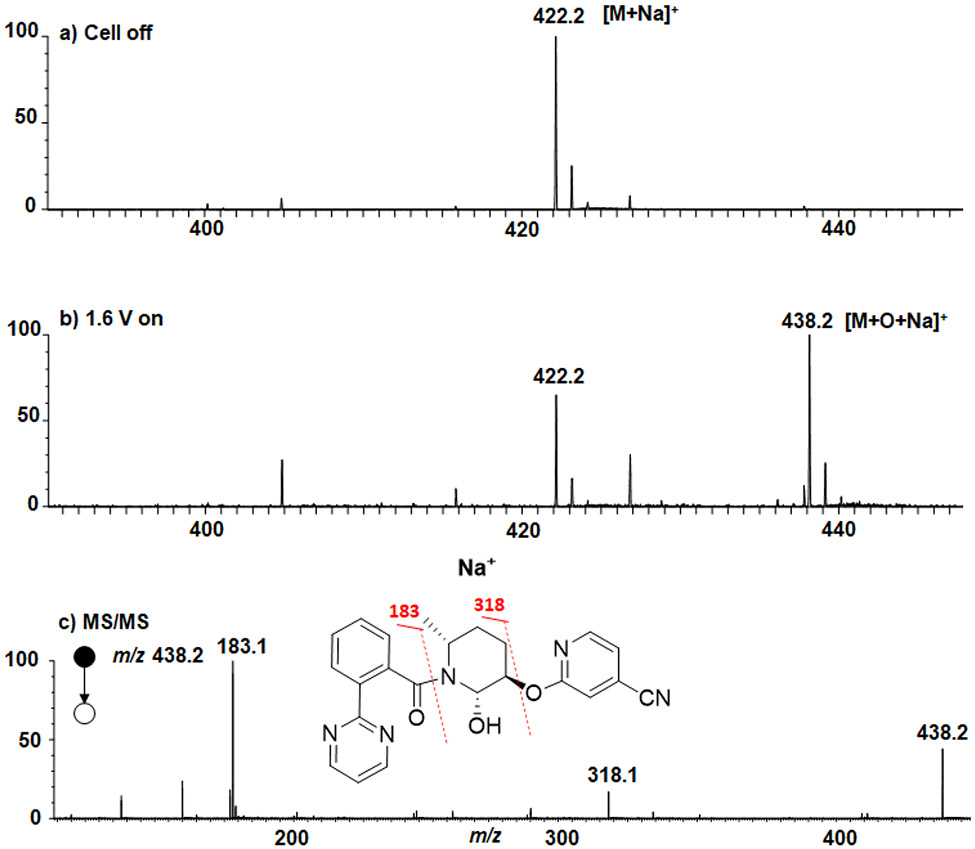

We first tested our hypothesis with the anodic oxidation of MK-8133 using an online EC/MS setup (Scheme 3). EC/MS, particularly with ESI or DESI as the ionization interface, is a very powerful tool to quickly screen different electrochemical experimental parameters (e.g., applied potential, sample flow rate and pH variation), since the electrochemical oxidation or reduction reaction is monitored online with MS.76-78 Oxidation of MK-8133 at a low concentration (100 μM) in water containing 10 mM NH4OAc was first conducted using the EC/MS apparatus (Scheme 3) (Data is shown in Figure S1; Supporting Information). With no potential applied to the cell, only protonated MK-8133 [(M+H)+] was detected at m/z 400 (Figure S1-a, Supporting Information). When a positive potential of 1.6 V was applied to the cell, a small peak corresponding to the oxidation product [M+O] + was detected at m/z 416 (Figure S1-b, Supporting Information). 1.6 V was the optimized potential. This value is close to the reported amide oxidation potentials varying from 1.47 to 2.21 V.79 However, when 20 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 (pH=7.0) in H2O was used, the oxidation yield was enhanced, likely attributed to the strong electrolytic character of the phosphate buffer, as shown in Figure 1. With no potential applied to the cell, only the sodium adduct ion of MK-8133 was detected at m/z 422 (Figure 1a). When a positive potential of 1.6 V was applied to the cell, the intensity of the m/z 422 ion decreased and another ion was observed at m/z 438 (Figure 1b), corresponding to the sodium adduct ion of M11. Upon collision induced dissociation (CID), the m/z 438 ion primarily yielded fragment ions at m/z 318 and 183, consistent with oxidation of piperidine fragment, as was anticipated (Figure 1c). The in-spectrum oxidation yield was estimated to be >50%, as the relative intensity of m/z 438 was higher than the remaining m/z 422. Note that the test of electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133 using our online EC/MS setup in this study was not only fast and took just few minutes, it also only consumed a minimal amount of sample (pico- to nano-moles of substrate).

Scheme 3.

EC/MS apparatus for online electrosynthesis monitoring/screening, and the optimization of the electrosynthesis parameters such as the initial concentration, solvents, applied potential, electrolysis time, pH and electrode materials.

Figure 1.

DESI-MS spectra acquired when a solution of 100 μM MK-8133 in water containing 20 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 (pH=7.0) was flowed through the thin-layer electrochemical cell a) without and b) with an applied 1.6 V; c) CID MS/MS spectrum of m/z 438.

It is also possible to isolate the electrochemically generated metabolite, M11. In an initial experiment, a higher concentration of MK-8133 (500 μM) in acetonitrile: aqueous 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (10:90; v/v) was continuously infused to the thin-layer μ-PrepCell™ (a flow cell, applied potential: 1.8 V) at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. The oxidation solution collected was recycled through the electrochemical cell for a second time to further enhance the oxidation conversion yield, which was found to approximately 40% by the LC/UV measurement (based on the ratio of the product UV absorption peak area at 254 nm vs. the total of UV absorption peak areas of the remaining reactant and the product at 254 nm, Figure S2-a, Supporting Information). A subsequent scale-up reaction for producing M11 by anodic oxidation of MK-8133 using the SynthesisCell™, a batch reactor cell with a large boron doped diamond (BDD) working electrode (3cm x 3cm) was conducted, employing the optimized conditions obtained from the online EC/MS screening. In the first attempt, 80 mL of 500 μM MK-8133 (16 mg starting material) was prepared in acetonitrile: aqueous sodium phosphate buffer (10:90; v/v) and added into the SynthesisCell™ (a batch reactor). A 21% conversion (3.4 mg product was obtained) was achieved within 3 h. Next, we attempted the oxidation of MK-8133 at high concentration to improve the product quantity. An 80 mL solution of 1.25 mM MK-8133 solution (40 mg starting material) in DMSO: aqueous 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (40:60; v/v) was added to the SynthesisCell™. The reaction was monitored by LC/MS, 11% conversion was observed (4.4 mg M11 produced) within 12 h, the highest conversion was achieved at approximately 17% yield (6.9 mg M11 produced) with reaction duration of about 72 h (Figure S2-b, Supporting Information). Although the conversion yield in the SynthesisCell™ was low (17% from a 72 h electrolysis), there was little byproduct formed and the remaining 80% was recoverable MK-8133. It is plausible that the working electrode of SynthesisCell™ needed to be cleaned following a long duration electrolytic reaction. Further improvement of the electrosynthetic yield may be possible by using a suitable porous electrode for electrolysis since the majority of parent MK-8133 remained. Remarkably, as shown below, the isolated product analyzed by solution NMR was shown to be identical to that isolated from the in vivo matrix with the correct regio- and stereochemical configuration.

NMR characterization of the electrochemically prepared M11 metabolite

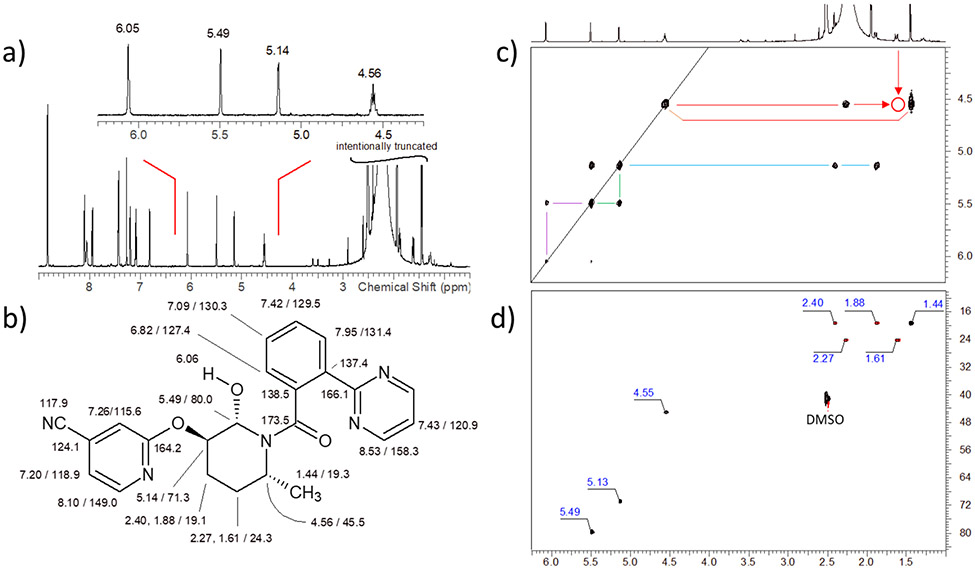

Definitive characterization of the oxidative metabolite, M11, of MK-8133 was accomplished using high resolution NMR techniques. Based on the multiplicity-edited HSQC spectrum of the metabolite, it was immediately apparent that only two, rather than the three methylene resonances of the parent molecule remained in the structure of the metabolite, indicating that, as expected, one of the methylenes had undergone oxidation in the electrochemical reaction. The two remaining methylene groups 2.27, 1.61/24.3 and 2.40, 1.88/19.1 ppm (1H/13C) were consistent with the proton and carbon chemical shifts of the 5- and 4-positions, respectively, of the piperidine ring of the parent. The resonances for the 6-methine (4.56/45.5 ppm) and the methyl (1.44, d, JHH = 6.9 Hz/19.3 ppm) were also comparable to those of the parent, strongly suggesting that oxidation had occurred at the 2-methylene (Figure 2). A new methine resonance was observed in the multiplicity-edited HSQC spectrum at 5.49/80.0 ppm, which is consistent with hydroxylation at the 2-position of the piperidine ring; the carbon chemical shift is consistent for an aminol carbon resonance. Homonuclear proton-proton correlations in the COSY spectrum afforded further confirmation of hydroxylation at the 2-position of the piperidine ring (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

a) 600 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of the M-11 metabolite of MK-8133 in d6-DMSO. b) 1H and 13C NMR resonance assignments for the M-11 metabolite made from the ensemble of 2D NMR data acquired for the sample. c) Pertinent region of the COSY spectrum showing correlations for the aliphatic resonances of the piperidine moiety in the structure. The proton resonating at 4.56 ppm affords correlations to the vicinal proton resonating at 2.27 ppm and to the methyl group resonating at 1.44 ppm. The open circle corresponds to a very weak correlation to the vicinal proton resonating at 1.61 ppm (see also the multiplicity-edited HSQC data shown in panel d) that is below the threshold used to plot the COSY data. d) Correlations for the aliphatic resonances of the M-11 metabolite observed in the multiplicity-edited HSQC spectrum.

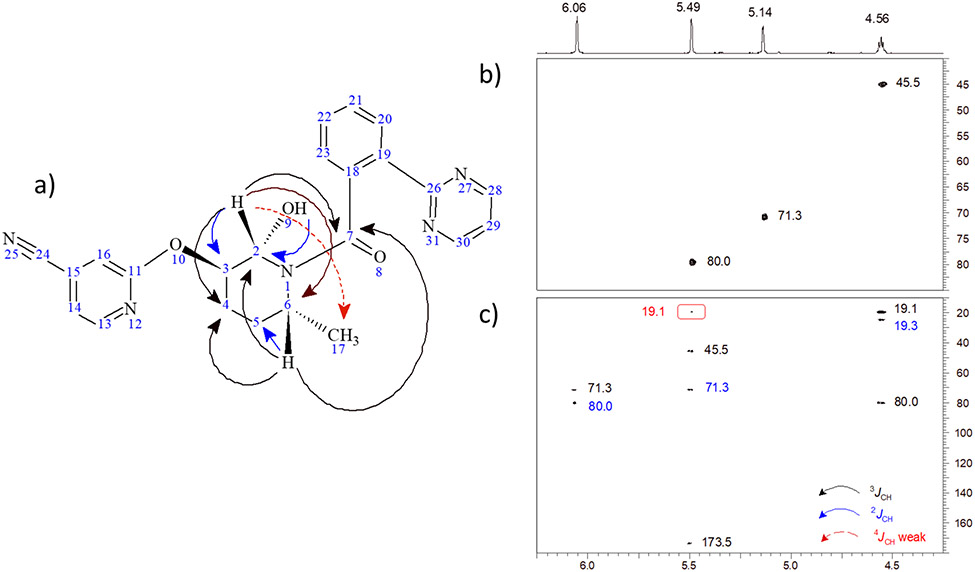

Long-range heteronuclear correlations were observed from the H2 methine proton (5.49 ppm) to carbons resonating at 173.5 (C7), 71.3 (C3), 45.5 (C6) and 19.1 (C4) ppm in an 8 Hz optimized HMBC experiment (Figure 3). The correlation to the C7 carbonyl was quite weak, which is to be expected based on the rotation about the bond between C7 and piperidine nitrogen. In similar fashion, correlations were observed from the H6 (4.56 ppm) proton to the C7 carbonyl, as well as carbons resonating at 80.0 (C2), 24.3 (C5) and 19.1 (C4) ppm (see numbered structure in Figure 3). In concert, these correlations unequivocally establish the site of electrochemical oxidation as the 2-position of the piperidine ring.

Figure 3.

a) Structure of the M-11 metabolite showing long-range 1H-13C correlations observed in the 8 Hz optimized HMBC spectrum. Correlation pathways are color-coded on the structure, with the most prevalent 3JCH correlations denoted by black arrows; 2JCH correlations are denoted by blue arrows; the single, weak 4JCH correlation observed is denoted by the dashed red arrow. b) Aliphatic moiety correlations in the multiplicity-edited HSQC spectrum of the M11 metabolite. c) Correlations observed in the 8 Hz optimized HMBC spectrum. Chemical shift labels are color-coded as a function of the long-range heteronuclear correlation pathway involved. The very weak 4JCH correlation from the proton resonating at 5.49 ppm to the methyl doublet is enclosed in the red box. It is interesting to note that no HMBC correlations were observed from the H3 proton resonating at 5.14 ppm to any of the aliphatic carbon resonances in the HMBC spectrum.

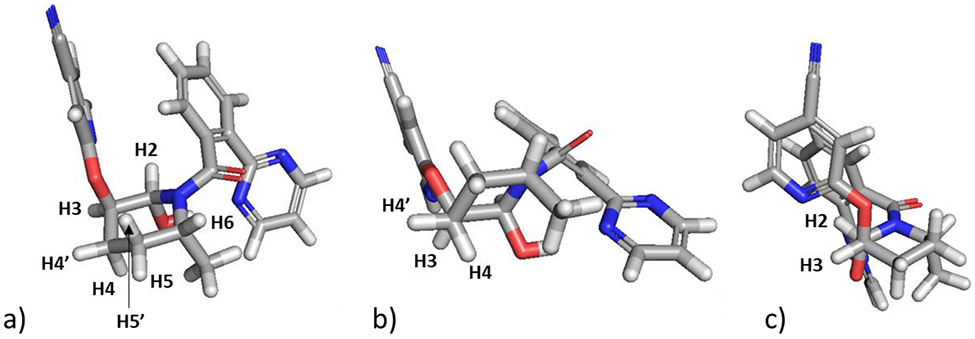

Analysis of a resolution enhanced 1H NMR spectrum of the M11 metabolite revealed the H2 methine proton as a doublet JHH = 2.5 Hz; the H3 methine proton was observed as an apparent quartet due to the three equivalent homonuclear couplings of JHH = 2.6 Hz. These homonuclear coupling constants are consistent with the gauche relationship between the H2 and the H4′ and H4″ protons with the H3 resonance, which can be seen looking along the C2-C3 bond axis of the energy-minimized structure of the M11 metabolite shown in Figure 4c. Further confirmation of the orientation of the 2-hydroxyl substituent was afforded by an observed NOE correlation between the 2-hydroxyl proton and the 6-methyl group in a NOESY spectrum (see Figure S10, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

a) Energy-minimized structure of the M11 metabolite of MK-8133. The orientation of the H3 resonance relative to the H2 and H4′ and H4″ resonances lead to dihedral angles that are consistent, based on the Karplus relationship, with the observed three small coupling constants exhibited by the H3 resonance. b) View along the C-4-C3 bond axis showing the gauche relationship of the H3 resonance to both H4 protons. c) View along the C2-C3 bond axis of the piperidine ring showing the gauche relationship of the H2 and H3 protons (see computational details below).

Electrochemical oxidation of MK-6096 to produce M10

Following the success in obtaining desired M11 metabolite from electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133, electrochemical oxidation of another parent compound, MK-6096, was investigated to determine whether the selective oxidation is broadly applicable and capable of producing the desired metabolite M10 (structure is shown in Scheme 1). As shown in Figure S3-a (Supporting Information), with no potential applied to the thin-layer μ-PrepCell™ flow cell, the protonated and sodiated MK-6096 ions were observed at m/z 421 and 443, respectively, when 100 μM MK-6096 in acetonitrile/water (50:50; v/v) containing10 mM ammonium formate and 1% formic acid (pH 2.2) was passed through the cell at a flow rate of 10 μL/min. When 1.8 V was applied to the BDD working electrode, two new ions were detected at m/z 437 and 459 (Figure S3-b, Supporting Information), corresponding to the protonated and sodiated oxidation products of MK-6096, respectively. Based on the relative intensities of the remaining MK-6096 peaks and the product peak, the yield for electrosynthesis of the oxidative metabolite M10 was estimated to be ≈40%. MS/MS of the m/z 459 ion predominantly afforded fragment ions at m/z 143, 169, 197 and 346, consistent with the sodium adduct of M10 structure (Figure S3-c, Supporting Information).

Based on the success of small-scale electrochemisty, the reaction was scaled up in an effort to produce usable quantities; mg quantities were obtained by using electrolysis in the SynthesisCell™. For the mg scale electrosynthesis experiment, 0.5 mg/mL solution of MK-6096 dissolved in acetonitrile/water (50:50; v/v) containing 10 mM ammonium formate and 1% formic acid (pH 2.2) was prepared and 80 mL of this solution was added to the SynthesisCell™. Conversion to the desired hydroxylated metabolite, M10, from MK-6096 was monitored by LC/MS. As shown in Figure S4 (Supporting Information), optimal conversion at about 14% occurred when the duration of the reaction was approximately 3.5 h. The desired hydroxylated metabolite was isolated (5.6 mg) and characterized by NMR analysis, which established the structure of the metabolite as M10. Detailed NMR analysis is shown in Figures 11S-16S and Table S3 (Supporting Information). Characterization of the structure of the isolated product of the electrochemical reaction confirmed that selective oxidation occurs at the C2 position of the MK-6096 piperidine ring.

Elucidation of electrochemical oxidation regioselectivity and stereoselectivity

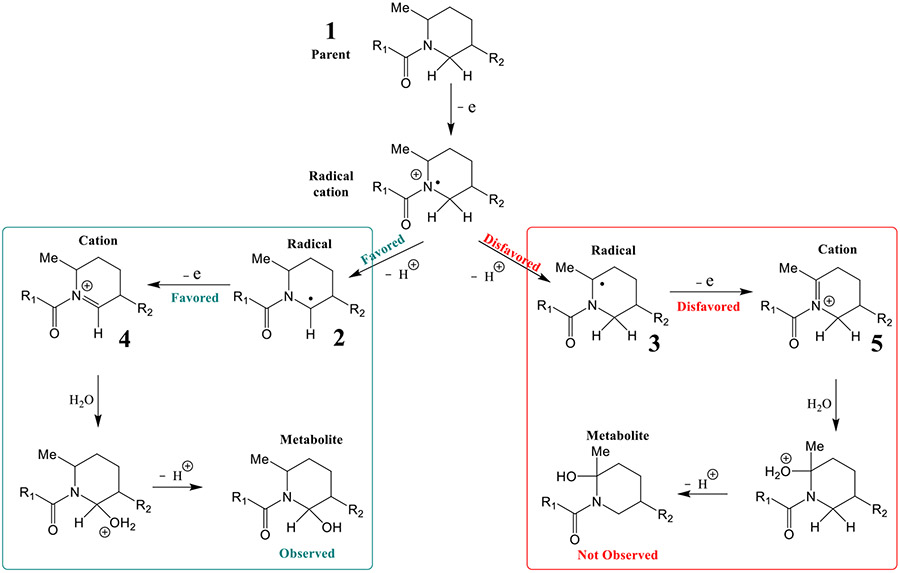

Scheme 4 shows the proposed mechanism for the electrochemical hydroxylation of MK-8133, which is similar to the anodic oxidation of an amide (Scheme 2). Hydroxylation on the tertiary carbon alpha to the nitrogen atom should be the predominant product since tertiary carbon radicals are normally more stable than secondary carbon radicals (3 in Scheme 4). However, our results indicate that the electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133 and MK-6096 yielded primarily hydroxylation products on the secondary carbon, alpha to the nitrogen atom.

Scheme 4.

The proposed mechanism for the electrochemical hydroxylation of MK-8133 and MK-6096.

A desire to rationalize this unexpected regioselectivity prompted further investigation using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Conformational space was exhaustively sampled using three conformer generators (a combination of rules-based and distance geometry-based methods) followed by molecular mechanics minimization using MMFF94, a workflow that has been previously published.80 Initial mechanistic rationale was explored based on comparing energies of the penultimate iminium cations, however, the relative energies of the cations predicted the formation of 5 and not 4 (Scheme 4). The relative stability of the iminium cations has, however, been used to rationalize the experimentally observed regioselectivity for a related series of compounds.81 Libendi, et al. proposed that the regioselectivity for a cyano or ester-substituted piperidine could be attributed to the relative stability of the LUMO energies of the cations (Figure S17 and additional discussion in the SI), however, as will be shown here, we propose that the regioselectivity for this class of reactions was instead governed by kinetic control of the deprotonation step.

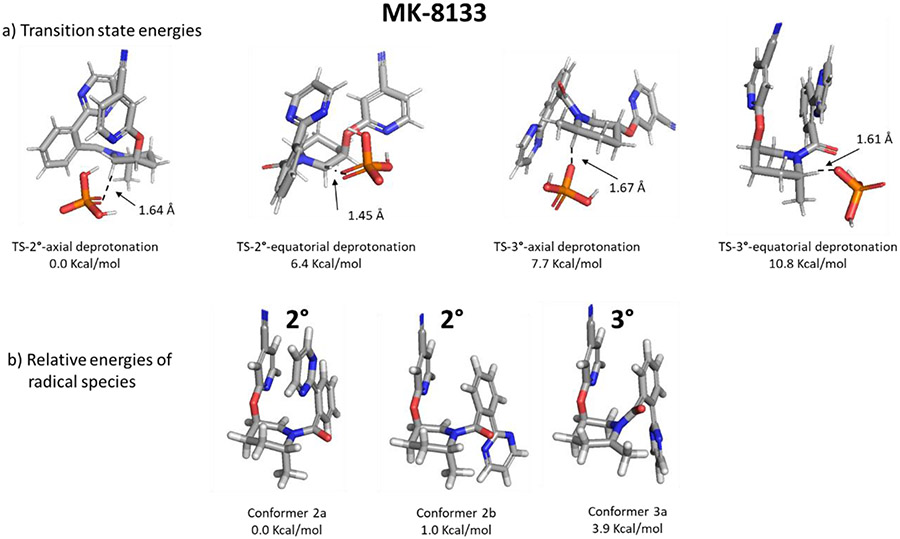

Transition states for the deprotonation step forming radical 2 from the radical cation of 1 were identified for MK-8133 (Figure 5). While there are several possibilities for what base may be deprotonating the intermediate radicals, we have selected to model a dihydrogen phosphate anion as the probable base present in the reaction solution. In the presence of an implicit solvent model, the preferred (quasiharmonic corrected Gibbs energy at 298 K) kinetic pathway is favored by 7.7 kcal/mol in support of formation of the observed product (see additional details in SI including Table S4). The lowest energy transition state for the observed secondary radical pathway derives from deprotonation of the axial proton from the lowest energy conformation of the MK-8133 starting material which adopts a chair conformation of the central piperidine core. Deprotonation of the axial proton allows for optimal overlap of the resultant p-orbitals of the carbon being deprotonated and the piperidine nitrogen, driving stabilization of the observed pathway. The higher energy of the TS for the analogous axial deprotonation at the tertiary α-carbon may be explained by steric strain from the equatorial methyl group with the carbonyl group bonded to N. The same steric and electronic factors are proposed to account for the selectivity observed with MK-6096.

Figure 5.

(a) Transition states for deprotonation, by a dihydrogen phosphate anion, of the radical cation leading to either the secondary or tertiary radicals. (b) Low energy conformations of the secondary and tertiary radicals for MK-8133. Carbon = grey, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue, hydrogen = white, phosphorous = orange.

Figure 5b depicts the three energetically significant conformers of the secondary and tertiary radicals of MK-8133. Conformer 2a (conformers of secondary radical are denoted “2°” while conformers of the tertiary radical are denoted “3°” in Figure 5) dominates the free energy surface and exhibits an intramolecular stacking interaction between the pyridine and biaryl systems as in the preferred transition state. Rotation about the amide-biaryl dihedral angle leads to conformer 2b of MK-8133 which is 1.0 Kcal/mol higher in energy. The tertiary radical is sterically unfavored owing to the methyl substituent at the radical center wanting to sit in the same space as the amide carbonyl which is not possible (this same steric argument explains why Libendi, et al., observed different regioselectivity for the less sterically bulky cyano moiety compared to the ester functionality81). Annotated as conformer 3a, the conformation of the tertiary radical is 3.9 Kcal/mol higher in energy than the lowest energy secondary radical conformer 2a. Additional steric repulsion eliminates the amide-biaryl rotamer equivalent to conformer 2b from consideration for the tertiary radical. In Figure S18, a series of calculations was performed on model systems containing either a truncated amide substituted piperidine or a modification of this core where the carbonyl was replaced with a methylene (shifts sp2 amide geometry to one that allows the piperidine nitrogen to be more pyramidal). Calculations indicate that the methylene species allows for a more stable tertiary radical compared to the secondary; when the carbonyl is in place, the secondary radical is preferred for reasons specified above.

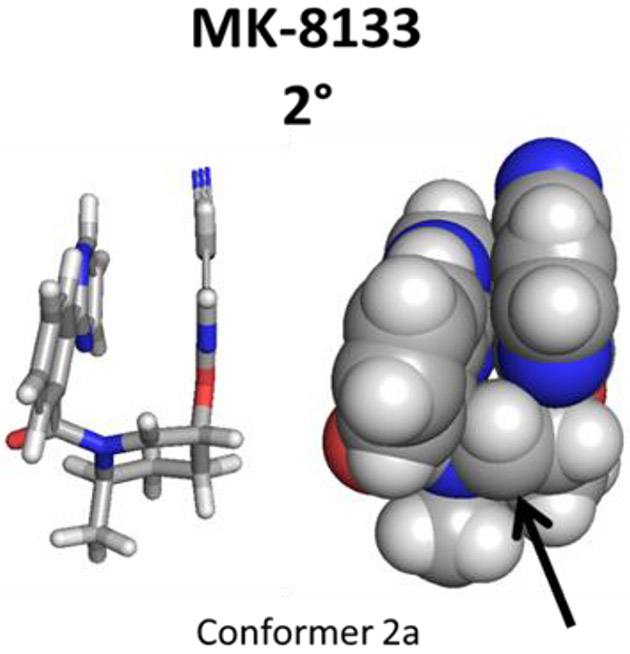

Following a second one-electron oxidation, 2 is converted to an iminium cation 4 (Scheme 4), which undergoes nucleophilic addition in the presence of water to give the 2-hydroxypiperidine product. It can be seen from Figure 6, that the global minima of the MK-8133 iminium cation generated from the radical precursor adopts a U-shaped conformation. Steric hindrance caused by the 2-phenylpyrimidine ring and cyanopyridine directs the nucleophilic attack to the bottom (re face) of N-acyl iminium ion in the axial position of the piperidine chair conformation. This is consistent with complete stereoselectivity observed during the electrochemical oxidation of MK-8133. Based on relative kinetic barrier heights and low energy conformations, we propose that the high regio- and stereoselectivity observed during electrochemical oxidation is driven by initial oxidation of the piperidine nitrogen of MK-8133, which then follows a reaction cascade driven largely by the steric properties of the piperidine exocyclic methyl group with a significant preference for deprotonation along the pathway towards the secondary radical derived product.

Figure 6.

Global minima conformation of the MK-8133 iminium cation 4 (derived from the secondary (2°) radical) shown in both a stick and space-filling representation. The arrow indicates favorable ‘bottom’ side approach in the axial position for the nucleophile whereas nucleophilic approach from the ‘top’ side is sterically blocked. Carbon = grey, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue, hydrogen = white.

Verification of the proposed factors governing selectivity observed with MK-8133 was conducted through electrochemical oxidation of a second orexin receptor antagonist, MK-6096, which possesses a similar molecular scaffold. As mentioned above, the product M10 from electrolytic oxidation of MK-6096 was isolated and characterized by NMR, which established the metabolite to be M10 with complete regio- and stereoselectivity similar to that of M11. Similar in vacuo radical stability calculations were carried out for MK-6096. Figure S19 shows the relative stabilities of transient radicals with the 2° α-carbon radicals having lower conformational energies compared to the 3° α-carbon radicals. Though the energy difference (1.0 Kcal/mol) is smaller compared to those calculated for MK-8133 (3.9 Kcal/mol), the MK-6096 carbon radical should predominantly form on the secondary α-carbon given the transition states identified for MK-8133 deprotonation. A larger number of conformers are energetically accessible for MK-6096, likely due to the methylene-spaced ether linkage, which affords more flexibility to the pyridine ring. This flexibility provides additional space for the biaryl to be positioned closing the gap on the energetic preference of the secondary radical. Experimentally, high regioselectivity was again observed. It can be seen in Figure S20 that MK-6096 possesses the same sterically blocked U-shaped conformation for the iminium cation generated from the secondary radical. For MK-6096, owing to similar conformer energies, two conformations must be considered, but as seen in Figure S20, it is evident that both conformations are more accessible for bottom side (as depicted) attack in the axial position of the chair conformation of the central piperidine. Transition states for the deprotonation step of MK-6096 were not undertaken as it is expected that the energetic preferences will mirror that of MK-8133.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the one-step electrochemical synthesis of milligram quantities of α-hydroxyl amide metabolites of MK-8133 and MK-6096 with exclusive regio- and stereoselectivity in aqueous media, the structures and stereochemical features confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. Based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the reaction regio- and stereoselectivity is governed by the relative stability of the transition states for deprotonation of the transient radical cations and steric hindrance directing axial addition experienced by the subsequent iminium species, respectively. Finally, it is shown that online EC/MS is a powerful tool in quickly identifying and optimizing the reaction conditions for desired products. Adapting this tool in the process can shorten the time cycle for electrochemical synthesis greatly.

Experimental Section

Electrochemical Synthesis

Small-scale reaction screening was undertaken using a lab-built EC/MS apparatus (Scheme 3) which consisted of a thin-layer electrochemical flow cell coupled with a Waters Xevo QTof mass spectrometer. Liquid sample desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) was used the EC/MS interface, as described previously in detail.82-84 The thin-layer μ-PrepCell™ (ANTEC BV, Netherlands) equipped with a glassy carbon working electrode (30x12 mm2) was used for oxidizing MK-8133; a BDD working electrode (30x12 mm2) was used to oxidize MK-6096. A HyREF™ electrode was used as a reference electrode and titanium was used as the counter electrode. The electrochemical reaction product flowed out of the cell via a short piece of fused silica connection capillary (i.d., 0.1 mm, length 4.0 cm) and underwent interactions with the charged microdroplets from DESI solvent spray for ionization. The capillary outlet was placed about 1 mm downstream from the DESI spray probe tip and kept in-line with the sprayer tip and the mass spectrometer’s inlet. The spray solvent for DESI was methanol/water (1:1 by volume) containing 1% acetic acid and a high voltage of 5 kV was applied to the spray probe. The flow rates for both the DESI probe solvent and the sample solutions passing through the electrochemical cell for electrolysis were 10 μL/min. The EC/MS setup allowed direct online monitoring of the electrosynthetic product or offline collection of the product from the μ-PrepCell™.

Large-scale electrochemical synthesis was undertaken using an apparatus consisting of a ROXY potentiostat (ANTEC BV, Netherlands) with an extended current range (up to 20 mA), controlled by Antec Dialogue software, and a bulk SynthesisCell™ (80 mL volume, ANTEC BV, Netherlands). The SynthesisCell™ was equipped with a flat smooth BDD working electrode (30x30 mm2), a HyREF™ reference electrode and an auxiliary electrode without a frit. The reaction solution consisted of 80 mL of 0.5 mg/mL of MK-8133 dissolved in DMSO/20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (40:60; v/v) or 80 mL of 1.2 mM of MK-6096 dissolved in acetonitrile/water (50:50; v/v) containing 10 mM ammonium formate and 1% formic acid. A square-wave pulse potential was applied to the SynthesisCell™ for oxidizing both MK-8133 and MK-6096. Under the optimized conditions, the potentials were +2.6 V (E1) and +2.2 V(E2) for oxidizing MK-8133 and the potentials were +1.8 V (E1) and +1.4 V (E2) for oxidizing MK-6096. Time intervals were 1,990 ms (t1) and 1,010 ms (t2). The progress of the synthesis was checked every 10 min by taking an aliquot of 1 μL from the SynthesisCell™ solution. The sample was diluted by a factor of 1000 prior to liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis (see details in Supporting Information). Both M11 obtained from MK-8133 electrolysis (6.9 mg, 17% yield) and M10 obtained from MK-6090 electrolysis (5.6 mg, 14% yield) were white powder solid.

NMR Characterization

High resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data were collected on either Bruker Avance III HD 700 MHz or Bruker Avance III HD 600 MHz NMR spectrometers (Bruker BioSpin Corporation, Billerica, MA); both spectrometers were equipped with a 1.7 mm HCN TCI MicroCryoProbe™. Approximately 50 μg of the purified hydroxylated metabolite of MK-6096 was dissolved in 35 μL of CD3CN and used for solution NMR experiments utilizing standard pulse sequences (proton, COSY, ME-HSQC, 8 Hz optimized HMBC, and ROESY with mixing times of 400 msec and 500 msec). Comparable NMR experiments were performed on a 50 μg of the purified hydroxylated M11 metabolite of MK-8133 dissolved in 35 μL of d6-DMSO.

Computational chemistry

Conformational searches were performed according to a computational workflow that combined several conformer generators with energetic evaluation using a series of force field and low level density functional methods.80 After identification of an initial conformer ensemble, more accurate Boltzmann distributions based on free energies (298K) were calculated using M06-2X/6-31G** for conformer distributions with diffuse functions added when calculating transition states for deprotonation. (see additional computational details in SI including quasiharmonic corrections to the transition state free energies).85 Stationary points were confirmed by vibrational frequency analysis. Transition states were confirmed with IRC (intrinsic reaction coordinate) following and confirmed minimizations to reactants and products. All calculations were run using Gaussian g09.d01 or g16.a03.86 Implicit solvation was modeled using SMD.87 For ground state species, analysis was focused on conformers contributing >2% to the overall ensemble for each species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF (CHE-2203284) and NIH (1R15GM137311-01) grants. The authors also wish to acknowledge the continuing support of this work by Kevin Bateman of the Department of Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug Metabolism, MRL, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ 07065, USA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supporting Information

Additional experimental procedure, MS, MS/MS, NMR and computational data are included. The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material.

References

- 1.Benca RM, Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Insomnia: A Review. Psych. Serv 2005, 56 (3), 332–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compernolle F; Saleh MA; Van den Branden S; Toppet S; Hoornaert G, Regioselective oxidation of piperidine-3 derivatives: a synthetic route to 2,5-substituted piperidines. J. Org. Chem 1991, 56 (7), 2386–2390. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelkonen O; Turpeinen M; Uusitalo J; Rautio A; Raunio H, Prediction of drug metabolism and interactions on the basis of in vitro investigations. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2005, 96 (3), 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plant N, Strategies for using in vitro screens in drug metabolism. Drug Discov. Today 2004, 9 (7), 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandon EFA; Raap CD; Meijerman I; Beijnen JH; Schellens JHM, An update on in vitro test methods in human hepatic drug biotransformation research: pros and cons. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2003, 189 (3), 233–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baillie TA, Metabolism and Toxicity of Drugs. Two Decades of Progress in Industrial Drug Metabolism. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2008, 21 (1), 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obach SR; Dalvie DK; Walker GS In Identification of drug metabolites, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 2012; pp 121–175. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stepan AF; Mascitti V; Beaumont K; Kalgutkar AS, Metabolism-guided drug design. MedChemComm 2013, 4 (4), 631–652. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusack KP; Koolman HF; Lange UEW; Peltier HM; Piel I; Vasudevan A, Emerging technologies for metabolite generation and structural diversification. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 23 (20), 5471–5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherry BD; Yin J; Fleitz FJ, Enantioselective Synthesis of a DualOrexin Receptor AntagonistIan K. Mangion. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 3458–3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schäfer HJ, Comparison of Chemical and Electrochemical Methods in Organic Synthesis. In Encyclopedia of Electrochemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyatt PB, Organic Electrochemistry (4th Edition), Edited by H. Lund and O. Hammerich, Marcel Decker, 2001, 1393. Electrochim. Acta 2002, 47, 1163. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn EJ; Rosen BR; Chen Y; Tang J; Chen K; Eastgate MD; Baran PS, Scalable and sustainable electrochemical allylic C-H oxidation. Nature 2016, 533 (7601), 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badalyan A; Stahl SS, Cooperative electrocatalytic alcohol oxidation with electron-proton-transfer mediators. Nature 2016, 535 (7612), 406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz L; Enders M; Elsler B; Schollmeyer D; Dyballa KM; Franke R; Waldvogel SR, Reagent- and Metal-Free Anodic C-C Cross-Coupling of Aniline Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56 (17), 4877–4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan M; Kawamata Y; Baran PS, Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev 2017, 117 (21), 13230–13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada Y; Chiba K, Redox-Tag Processes: Intramolecular Electron Transfer and Its Broad Relationship to Redox Reactions in General. Chem. Rev 2018, 118 (9), 4592–4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moeller KD, Using Physical Organic Chemistry To Shape the Course of Electrochemical Reactions. Chem. Rev 2018, 118 (9), 4817–4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francke R; Little RD, Redox catalysis in organic electrosynthesis: basic principles and recent developments. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43 (8), 2492–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu N; Sauer GS; Lin S, A general, electrocatalytic approach to the synthesis of vicinal diamines. Nature Protocols 2018, 13 (8), 1725–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahanty K; Maiti D; De Sarkar S, Regioselective C─H Sulfonylation of 2H-Indazoles by Electrosynthesis. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85 (5), 3699–3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan Y; Lei A, Is electrosynthesis always green and advantageous compared to traditional methods? Nature Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schotten C; Nicholls TP; Bourne RA; Kapur N; Nguyen BN; Willans CE, Making electrochemistry easily accessible to the synthetic chemist. Green Chem. 2020, 22 (11), 3358–3375. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leech MC; Lam K, A practical guide to electrosynthesis. Nature Rev. Chem 2022, 6 (4), 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elsler B; Schollmeyer D; Dyballa KM; Franke R; Waldvogel SR, Metal- and reagent-free highly selective anodic cross-coupling reaction of phenols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 5210–5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer HJ, CC bonds at anodes and cathodes. Angew. Chem 1981, 93, 978–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang F; Moeller KD, Intramolecular Anodic Olefin Coupling Reactions: The Effect of Polarization on Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12414–12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H-C; Moeller KD, Intramolecular Anodic Olefin Coupling Reactions: Use of the Reaction Rate To Control Substrate/Product Selectivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49, 8004–8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morofuji T; Shimizu A; Yoshida J. i., Metal- and Chemical-Oxidant-Free C-H/C-H Cross-Coupling of Aromatic Compounds: The Use of Radical-Cation Pools. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 7259–7262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leow WR; Lum Y; Ozden A; Wang Y; Nam D-H; Chen B; Wicks J; Zhuang T-T; Li F; Sinton D; Sargent EH, Chloride-mediated selective electrosynthesis of ethylene and propylene oxides at high current density. Science 2020, 368, 1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu X; Nie L; Zhang G; Lei A, Electrochemical Oxidative [4+2] Annulation for the π-Extension of Unfunctionalized Hetero-biaryl Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 15238–15243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattler LE; Otten CJ; Hilt G, Alternating Current Electrolysis for the Electrocatalytic Synthesis of Mixed Disulfide via Sulfur-Sulfur Bond Metathesis towards Dynamic Disulfide Libraries. Chem. - Eur. J 2020, 26 (14), 3129–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W; Carpenter KL; Lin S, Electrochemistry Broadens the Scope of Flavin Photocatalysis: Photoelectrocatalytic Oxidation of Unactivated Alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng 2020, 59, 409–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu X; Zhou X; Jing Y; Li Y, Electrochemical synthesis of urea on MBenes. Nature Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu C; Ma B; Gao Z; Dong X; Zhao C; Liu H, Electrochemical DNA synthesis and sequencing on a single electrode with scalability for integrated data storage. Science Adv. 2021, 7 (46), eabk0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shono T; Matsumura Y; Tsubata K, Electroorganic chemistry. 46. A new carbon-carbon bond forming reaction at the .alpha.-position of amines utilizing anodic oxidation as a key step. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 1172. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F; Rafiee M; Stahl SS, Electrochemical Functional-Group-Tolerant Shono-type Oxidation of Cyclic Carbamates Enabled by Aminoxyl Mediators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6686 –6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones AM; Banks CE, The Shono-type electroorganic oxidation of unfunctionalised amides. Carbon─carbon bond formation via electrogenerated N-acyliminium ions Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2014, 10, 3056–3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diehl G; Karst U, On-line electrochemistry – MS and related techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2002, 373, 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Permentier HP; Bruins AP; Bischoff R, Electrochemistry-mass spectrometry in drug metabolism and protein research. Mini Rev. Med. Chem 2008, 8, 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J; Dewald HD; Chen H, Online Coupling of Electrochemical Reactions with Liquid Sample Desorption Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 9716–9722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao P; Wang Q; Kaur M; Kim Y-I; Dewald HD; Mozziconacci O; Liu Y; Chen H, Absolute Quantitation of Proteins by Coulometric Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2020, 92, 7877–7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chintalapudi K; Badu-Tawiah AK, An integrated electrocatalytic nESI-MS platform for quantification of fatty acid isomers directly from untreated biofluids. Chem. Sci, 2020, 11, 9891–9897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang S; Fan L; Cheng H; Yan X, Incorporating electro-epoxidation into electrospray ionization mass spectrometry for simultaneous analysis of negatively and positively charged unsaturated glycerophospholipids. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2020, 32 (9), 2288–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu J; Zhang N; Zhang P-K; Chen Y; Xia X-H; Chen H-Y; Xu J-J, Coupling a Wireless Bipolar Ultramicroelectrode with Nano-electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: Insights into the Ultrafast Initial Step of Electrochemical Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2020, 59, 18244–18248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown TA; Chen H; Zare RN, Identification of Fleeting Electrochemical Reaction Intermediates Using Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 7274–7277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown TA; Chen H; Zare RN, Detection of the Short-Lived Radical Cation Intermediate in the Electrooxidation of N,N-Dimethylaniline by Mass Spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2015, 54, 11183–11185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiu R; Zhang X; Luo H; Shao Y, Mass spectrometric snapshots for electrochemical reactions. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 6684–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu J; Zhou Y; Hua X; Liu S; Zhu Z; Yu X-Y, Capturing the transient species at the electrode–electrolyte interface by in situ dynamic molecular imaging. Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 10952–10955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Z; Zhang Y; Liu B; Wu K; Thevuthasan S; Baer DR; Zhu Z; Yu X-Y; Wang F, In Situ Mass Spectrometric Monitoring of the Dynamic Electrochemical Process at the Electrode–Electrolyte Interface: a SIMS Approach. Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 960–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khanipour P; Löffler M; Reichert AM; Haase FT; Mayrhofer KJJ; Katsounaros I, Cover Picture: Electrochemical Real-Time Mass Spectrometry (EC-RTMS): Monitoring Electrochemical Reaction Products in Real Time (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 22/2019). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 7145–7145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hasa B; Jouny M; Ko BH; Xu B; Jiao F, Flow Electrolyzer Mass Spectrometry with a Gas-Diffusion Electrode Design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (6), 3277–3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu J; Yu K; Zhang H; He J; Jiang J; Luo H, Mass spectrometric detection of fleeting neutral intermediates generated in electrochemical reactions. Chem. Sci 2021, 12 (27), 9494–9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu J; Wang T; Zhang WJ; Hao H; Yu Q; Gao H; Zhang N; Chen Y; Xia XH; Chen HY, Dissecting the Flash Chemistry of Electrogenerated Reactive Intermediates by Microdroplet Fusion Mass Spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 133 (34), 18642–18646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan Q; Chen S; Badu-Tawiah AK, An integrated mass spectrometry platform enables picomole-scale real-time electrosynthetic reaction screening and discovery. Chem. Sci, 2018, 9, 5724–5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q; Wang Q; Zhang Y; Mohamed YM; Pacheco C; Zheng N; Zare RN; Chen H, Electrocatalytic redox neutral [3 + 2] annulation of N-cyclopropylanilines and alkenes. Chem. Sci 2020, 12 (3), 969–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng H; Yang T; Edwards M; Tang S; Xu S; Yan X, Picomole-Scale Transition Metal Electrocatalysis Screening Platform for Discovery of Mild C─C Coupling and C─H Arylation through in Situ Anodically Generated Cationic Pd. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 1306–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jurva U; Wikstrom HV; Weidolf L; Bruins AP, Comparison between electrochemistry/mass spectrometry and cytochrome P450 catalyzed oxidation reactions. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2003, 17 (8), 800–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karst U, Electrochemistry/mass spectrometry (EC/MS)--a new tool to study drug metabolism and reaction mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43 (19), 2476–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansson Mali'n T; Weidolf L; Castagnoli N Jr; Jurva U, P450-catalyzed vs. electrochemical oxidation of haloperidol studied by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2010, 24 (9), 1231–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nouri-Nigjeh E; Bischoff R; Bruins AP; Permentier HP, Electrochemistry in the mimicry of oxidative drug metabolism by cytochrome P450s. Curr. Drug Metab 2011, 12 (4), 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lohmann W; Baumann A; Karst U, Electrochemistry and LC-MS for metabolite generation and identification: Tools, technologies, and trends. LCGC North Am. 2010, 28 (6), 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stalder R; Roth GP, Preparative Microfluidic Electrosynthesis of Drug Metabolites. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 4 (11), 1119–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mautjana NA; Estes J; Eyler JR; Brajter-Toth A, Antioxidant Pathways and One-Electron oxidation of Dopamine and Cysteine in Electrospray and On-line Electrochemistry Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Electroanalysis 2008, 20, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Permentier HP; Bruins AP; Bischoff R, Electrochemistry-mass Spectrometry in drug metabolism and protein research. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem 2008, 8, 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gun J; Bharathi S; Gutkin V; Rizkov D; Voloshenko A; Shelkov R; Sladkevich S; Kyi N; Rona M; Wolanov Y; Rizkov D; Koch M; Mizrahi S; Pridkhochenko PV; Modestov A; Lev O, Highlights in Coupled Electrochemical Flow Cell-Mass Spectrometry, EC/MS. Israel J. Chem 2010, 50, 360–373. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jurva U; Wikstrom HV; Bruins AP, In vitro mimicry of metabolic oxidation reactions by electrochemistry/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2000, 14, 529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karst U, Electrochemistry/mass spectrometry (EC/MS)-A new tool to study drug metabolism and reaction mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 2476–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bussy U; Boujtita M, Advances in the Electrochemical Simulation of Oxidation Reactions Mediated by Cytochrome P450. Chem. Res. Toxico 2014, 27, 1652–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nowak P; Woźniakiewicz M; Kościelniak P, Simulation of drug metabolism. TrAC 2014, 59, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuan T; Permentier H; Bischoff R, Surface-modified electrodes in the mimicry of oxidative drug metabolism. TrAC 2015, 70, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedersen A; Ambach L; König S; Weinmann W, Electrochemical simulation of Phase I metabolism for 21 drugs using four different working electrodes in an automated screening setup with MS detection. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 2607–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shono T., Synthesis of alkaloidal compounds using an electrochemical reaction as a key step. Top. Curr. Chem 1988, 148 (Electrochemistry 3), 131–51. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siu T; Li W; Yudin AK, Parallel Electrosynthesis of α-Alkoxycarbamates, α-Alkoxyamides, and α-Alkoxysulfonamides Using the Spatially Addressable Electrolysis Platform (SAEP). J. Combin. Chem 2000, 2 (5), 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yudin AK; Siu T, Combinatorial electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2001, 5 (3), 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng Q; Chen H, Development and Applications of Liquid Sample Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Ann. Rev. Anal. Chem 2016, 9 (1), 411–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu P; Zheng Q; Dewald HD; Zhou R; Chen H, The study of electrochemistry with ambient mass spectrometry. TrAC 2015, 70, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou F; Berkel GJV, Electrochemistry Combined Online with Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 1995, 67 (97), 3643–3649. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Golub T; Becker JY, Electrochemical oxidation of amides of type Ph 2 CHCONHAr. Org. Biomol. Chem 2012, 10 (19), 3906–3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sherer EC; Lee CH; Shpungin J; Cuff JF; Da C; Ball R; Bach R; Crespo A; Gong X; Welch CJ, Systematic Approach to Conformational Sampling for Assigning Absolute Configuration Using Vibrational Circular Dichroism. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57 (2), 477–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Libendi SS; Demizu Y; Matsumura Y; Onomura O, High regioselectivity in electrochemical α-methoxylation of N-protectedcyclic amines. Tetrahedron 2008, 64 (18), 3935–3942. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu M; Liu Y; Helmy R; Martin GE; Dewald HD; Chen H, Online Investigation of Aqueous-Phase Electrochemical Reactions by Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 1676–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cai Y; Zheng Q; Chen H; Liu Y; Helmy R; Loo JA, Integration of electrochemistry with ultra-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Mass. Spectrom 2015, 21, 341–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng Q; Zhang H; Tong L; Wu S; Chen H, Cross-Linking Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry for Probing Protein Three-Dimensional Structures. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 8983–8991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao Y; Truhlar DG, The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Mennucci B; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Caricato M; Li X; Hratchian HP; Izmaylov AF; Bloino J; Zheng G; Sonnenberg JL; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd J; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Rega N; Millam NJ; Klene M; Knox JE; Cross JB; Bakken V; Adamo C; Jaramillo J; Gomperts R; Stratmann RE; Yazyev O; Austin AJ; Cammi R; Pomelli C; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Zakrzewski VG; Voth GA; Salvador P; Dannenberg JJ; Dapprich S; Daniels AD; Farkas Ö; Foresman JB; Ortiz JV; Cioslowski J; Fox DJ Gaussian 09, Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marenich AV; Cramer CJ; Truhlar DG, Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Chem. Phys. B 2009, 113 (18), 6378–6396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.