Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma in humans and afflicts more than 58 million people worldwide. The HCV envelope E1 and E2 glycoproteins are essential for viral entry and comprise the primary antigenic target for neutralizing antibody responses. The molecular mechanisms of E1E2 assembly, as well as how the E1E2 heterodimer binds broadly neutralizing antibodies, remain elusive. Here, we present the cryo–electron microscopy structure of the membrane-extracted full-length E1E2 heterodimer in complex with three broadly neutralizing antibodies—AR4A, AT1209, and IGH505—at ~3.5-angstrom resolution. We resolve the interface between the E1 and E2 ectodomains and deliver a blueprint for the rational design of vaccine immunogens and antiviral drugs.

Despite the need for a hepatitis C virus (HCV) prophylactic vaccine, vaccine development has been limited by the extensive sequence diversity of the virus and the lack of structural information on the vaccine target: the envelope glycoprotein E1E2 complex (1, 2). Previous studies suggest that eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which target E1E2 during infection, correlates with viral clearance and protection in humans (3–5), whereas passively administered bNAbs protect against infection in animal models (6–8). These observations provide a motivation for the development of an HCV vaccine aimed at inducing bNAbs (1).

HCV is an enveloped, single-strand, positive-sense RNA virus from the Flaviviridae family. The RNA genome encodes a single polyprotein that is processed by host and viral proteases into three structural and seven nonstructural proteins (9). The E1 and E2 envelope proteins associate to form a glycoprotein complex located on the outside of the virus that drives entry into hepatocytes (9). The E2 subunit includes the receptor-binding domain and engages scavenger-receptor class B1 (SR-B1) and the tetraspanin CD81, whereas E1 is assumed to be the fusogenic subunit because it contains the putative fusion peptide (pFP) (10–12). Because the E1E2 complex is the only viral protein on the surface of the virus, it is the sole target for bNAbs and thus an attractive candidate for structure-based immunogen design.

High-resolution structure determination of the full-length E1E2 heterodimer has been hindered by intrinsic flexibility, conformational heterogeneity, disulfide-bond scrambling, and extensive glycosylation (2, 13–16). The glycan shield not only protects E1E2 from immune recognition but also facilitates assembly and viral infection (16–18). At the present time, structural information is limited to truncated versions of recombinant E1 or E2, or small peptides (20–28). Moreover, antigenic region 4 (AR4), which includes the epitopes of several broad and potent HCV bNAbs such as AR4A and AT1618, has eluded structural characterization (5, 28). Whereas membrane-associated E1E2 displays AR4 and binds bNAb AR4A efficiently, soluble HCV E1E2 glycoprotein complex usually does not, suggesting that AR4 represents a metastable domain (18, 29–31). Using an optimized expression and purification scheme, we discovered that the coexpression and binding of AR4A stabilized the assembly of the full-length E1E2 heterodimer, producing a promising sample for structure determination. We subsequently determined the cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the E1E2 heterodimer in complex with the fragment antigen binding (Fab) domain of AR4A and the Fabs of the bNAbs IGH505 and AT1209, providing a molecular description of three key neutralizing epitopes that pave the way for structure-based vaccine design.

Results

Purification and overall fold of E1E2

The full-length HCV envelope glycoprotein complex E1E2 described here is derived from the genotype 1a strain AMS0232, which was obtained from an HCV-infected individual enrolled in the MOSAIC cohort (32). The AMS0232-based pseudovirus (HCVpp) was more resistant to neutralization by polyclonal HCV-positive sera than the reference strain H77 but was sensitive to AR4A, making it suitable for pursuing a complex with this bNAb (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A).

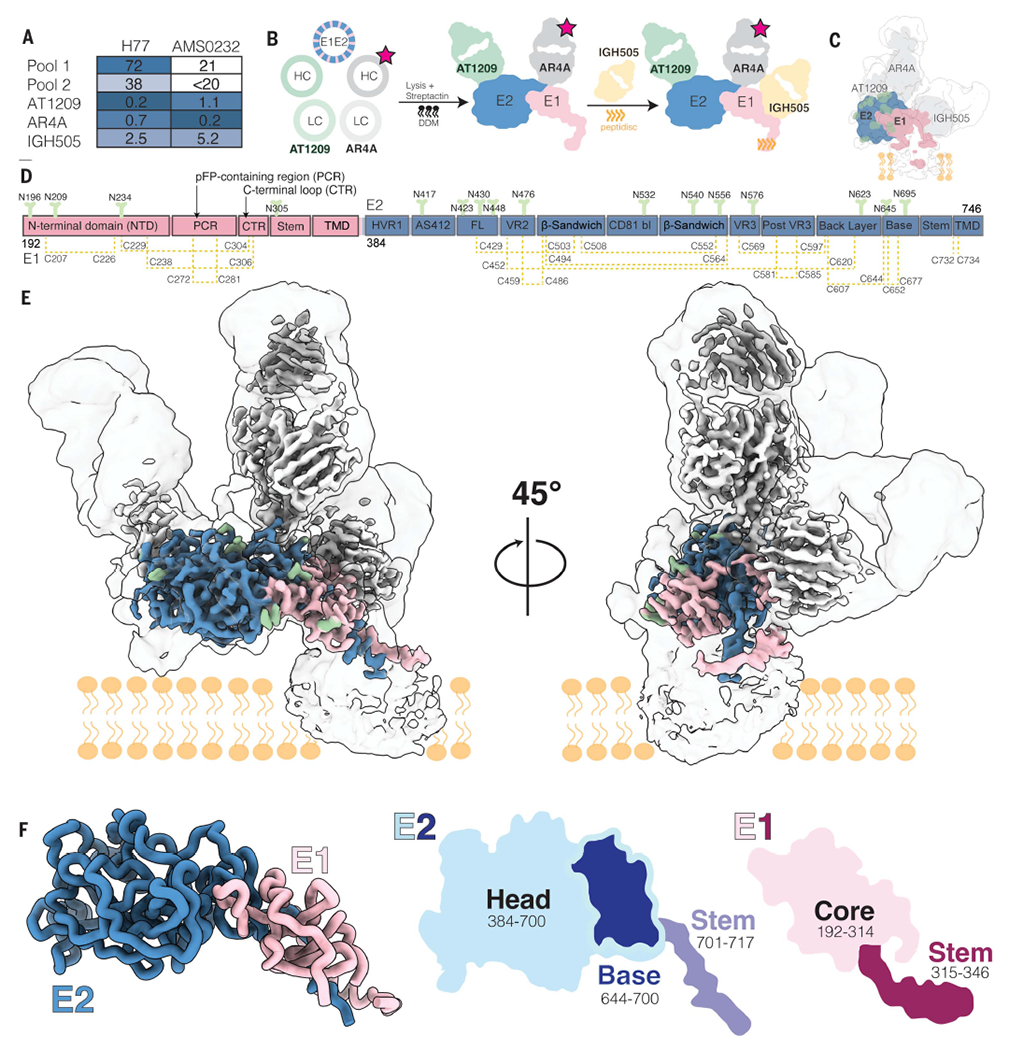

Fig. 1. Cryo-EM structure of the HCV E1E2 heterodimer in complex with bNAbs AT1209, IGH505, and AR4A.

(A) Sensitivity of AMS0232 and H77 pseudovirus to neutralization by polyclonal serum pools and bNAbs AT1209, IGH505, and AR4A. The serum dilutions and antibody concentrations (in μg/ml) at which HCV infectivity is inhibited by 50% (ID50 and IC50, respectively) are listed. Values are the mean of two or three independent experiments. Darker shading indicates increased sensitivity. (B) Schematic representation of the purification of full-length HCV E1E2. The stars indicate StrepII-tag. DDM, dodecyl-β-d-maltoside; HC, heavy chain; LC, light chain. (C) Cartoon representation of the cryo-EM map density of E1 and E2 in complex with AT1209, IGH505, and AR4A Fabs overlayed with the low-resolution cryo-EM map at a threshold of 0.1 in ChimeraX. (D) Schematic representation of the full-length E1E2 AMS0232 construct. The E1 and E2 subunits are shown in pink and blue, respectively, with the different subdomains indicated. N-linked glycans are shown in green and disulfide bonds in yellow. The same color coding is used in (E) and (F). (E) Cryo-EM map showing the density of the full-length E1E2 in complex with the three bNAbs. (F) View of E1E2 heterodimer. A cartoon representation of the head and stem regions of E2 with the newly resolved base region are highlighted.

We coexpressed StrepII-tagged AR4A Fab with the E1E2 heterodimer and used StrepTactin purification to produce E1E2 in complex with AR4A (Fig. 1B). Negative-stain electron microscopy (NS-EM) revealed that E1E2 glycoprotein in complex with AR4A is more homogeneous than unbound E1E2 glycoprotein complexes, making AR4A-bound E1E2 more suitable for high-resolution structural characterization using cryo-EM (fig. S1, B and C). Binding of monoclonal antibodies and CD81 to E1E2, unbound or in complex with AR4A, was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (fig. S1, D and E). Antibody binding correlated with neutralization of the parental pseudo-virus, suggesting that AR4A-extracted E1E2 glycoprotein complex is antigenically analogous to functional E1E2 (fig. S1F). Additionally, we observed low binding of non-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies CBH-4B, CBH-4D, and CBH-4G in AR4A-extracted E1E2 glycoprotein complex, likely because of the steric blockage of AR4A (33).

For cryo-EM studies, we coexpressed the full-length E1E2 glycoprotein complex with the AT1209 Fab (34) and the StrepII-tagged AR4A Fab to increase E1E2 stability. The complex was extracted from the membrane and reconstituted into peptidiscs before the addition of the IGH505 Fab (Fig. 1B) (35, 36). To prevent mispairing of the AR4A and AT1209 heavy and light chains during synthesis, we used a CrossMAb version of the AT1209 Fab (CrossFab) (37).

Although we were able to isolate a biochemically well-behaved complex of E1E2 bound to Fabs, the relatively small size and flexibility of the complex presented substantial challenges for high-resolution reconstruction. To overcome these challenges, we used 3D Variability Analysis in cryoSPARC (38) to resolve both discrete and flexible conformations of the E1E2 heterodimer bound to three Fabs. This strategy allowed us to determine the structures of the ectodomains at 3.5-Å resolution and the flexible domains at 3.8-Å resolution (fig. S2). This structure was sufficient to model 51% of E1 and 82% of E2, including the interface of these two envelope glycoproteins; the epitopes of bNAbs AR4A, AT1209, and IGH505; and the glycan shield (Fig. 1, C to E, and fig. S3). Regions that were not modeled in the E1E2 heterodimer bound to three Fabs included the disordered hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) in E2 (amino acids 384 to 410), amino acids 412 to 419 in antigenic site 412 (AS412, amino acids 412 to 423) in E2, the transmembrane domains (TMDs) in E1 and E2 (amino acids 350 to 382 and 718 to 746, respectively), and lastly, the pFP-containing region (PCR) in E1 (residues 257 to 294) (figs. S3 and S4A). Although the E1 and E2 TMDs were unresolved, we combined the AlphaFold-predicted structure of these domains with our experimentally derived model to gain insight into the positioning of E1E2 relative to the membrane (fig. S4D).

Subdomain organization of E1 and E2

E2 contains three subdomains—the head, stem, and TMD. Our structure of the E2 head domain in the E1E2 complex agrees well with previously reported crystal structures of recombinant E2, including the most complete crystal structure [root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.805 Å, Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 6MEI] (fig. S4A). However, our E1E2 structure reveals two previously unresolved regions of E2: (i) an extended loop interrupted by a small antiparallel β sheet in the E2 head that we term the “base” (residues 645 to 700) and (ii) the stem (residues 701 to 717), which connects the base with the TMD (amino acids 718 to 746; Figs. 1F and 2A). The E2 head consists of a central β-sandwich core (residues 484 to 517 and 535 to 568), a front layer and a back layer (residues 420 to 458 and 596 to 643, respectively), the apical CD81 binding site (amino acids 518 to 534), HVR1 (residues 384 to 410), AS412 (residues 412 to 423), variable regions 2 and 3 (VR2, residues 459 to 483; VR3, residues 569 to 579), and the newly resolved base (residues 645 to 700).

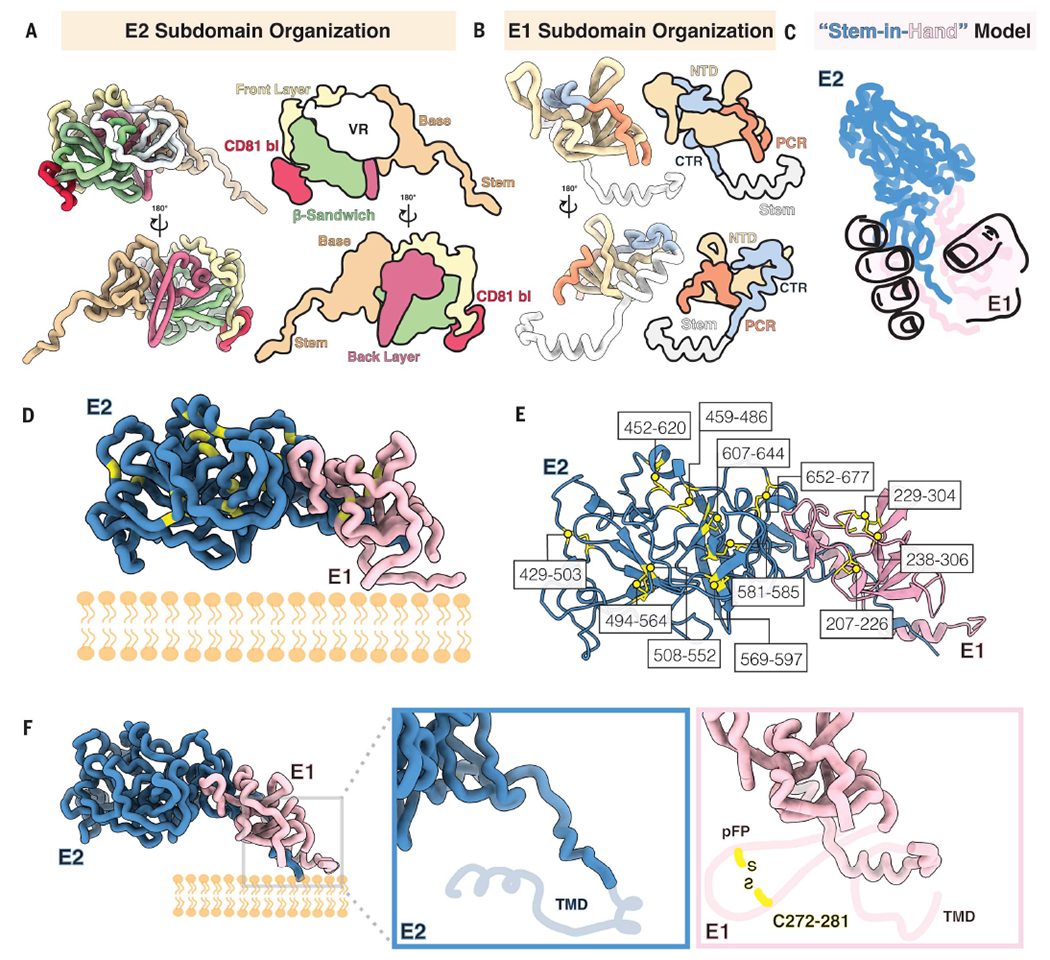

Fig. 2. Subdomain organization and disulfide bonds of E1 and E2.

(A to F) View of E1E2 subdomains. In (A), each domain in E2 is colored and represented as licorice and cartoon. The E2 stem and base are shown in tan, followed by the back layer in magenta, the β sandwich in green, the front layer in yellow, and the CD81 binding site in red; all variable regions (VR) are shown in white. In (B), the E1 NTD is shown in yellow, whereas the PCR is shown in orange, the CTR in shown in blue, and the stem region is colored white. Shown in (C) is a stem-in-hand model of E1 (hand) grasping the stem of E2. In (D), the location of each cysteine in E1E2 is highlighted in yellow and further outlined and numbered in (E). Shown in (F) are close-ups of the E1E2 C-terminal region to highlight the missing regions in this highly flexible region: the TMD in E2 and two helices in E1 that comprise the E1 pFP-containing region and contain a conserved disulfide bond as well as a TMD in E1 (indicated by the light pink cartoon line). The missing regions are depicted according to AlphaFold predictions.

In E1, our structure contains well-resolved density for the core (residues 192 to 314) and the stem (residues 315 to 346) (Fig. 1F). The E1 core includes the N-terminal domain (NTD; residues 192 to 248), the PCR (residues 249 to 299), and a C-terminal loop region (CTR; residues 300 to 314) that connects the PCR to the stem (Figs. 1F and 2B). The conformation of the E1 NTD differs substantially from that of a prior crystal structure of the soluble E1 NTD (25) (PDB ID 4UOI), suggesting that the presence of E2 is required for proper E1 folding. However, a prior crystal structure of 10 residues within the E1 stem (residues 314 to 324) aligns well with our atomic model of the E1 stem (residues 310 to 328) (RMSD = 0.254 Å) (fig. S4A) (27) (Figs. 1F and 2B and fig. S4, A and C).

Disulfide bond networks of E1 and E2

The cysteine residues in E1E2 are highly conserved, but disulfide-bond patterns differ between recombinant E2 structures (19–21, 39), whereas the disulfide bond network in E1 has remained largely elusive (40). In our cryo-EM structure, E2 is stabilized by nine disulfide bonds: C429-C503, C452-C620, C459-C486, C494-C564, C508-C552, C569-C597, C581-C585, C607-C644, and C652-C677 (Fig. 2, D to F) (C, Cys). Meanwhile, E1 is held together by four disulfide bonds: C207-C226, C229-C304, C238-C306, and C272-C281 (Fig. 2, D to F). The E2 disulfide network is consistent with that in previous crystal structures of the E2 ecto-domain in complex with HEPC3 or HEPC74, although the C652-C677 cysteine pair in the E2 base was missing from these structures (21). By contrast, in most recombinant E2 structures and a structure of E2 core in complex with AR3C (PDB ID 4MWF), the cysteines at positions C569, C581, C585, and C597 are paired differently (fig. S3). We directly observed three disulfide bonds in E1 (C207-C226, C229-C304, and C238-C306), and AlphaFold predicted the presence of a fourth disulfide bridge between C272 and C281, which would connect two amphipathic helices of the pFP. The proximity of the cysteine pairs C494-C564 to C508-C552, C452-C620 to C459-C486, and C581-C585 to C569-C597 and C607-C644 in E2, as well as the close proximity of the three observed disulfide bonds in E1, likely allows disulfide scrambling resulting in heterogeneous E1E2 proteins (Fig. 2, E and F) (19, 20, 39, 41, 42).

The E1E2 interface

To illustrate the E1E2 interface, we posit the “stem-in-hand” model, wherein the E1 ectodomain wraps around the E2 stem and interacts with the base of E2 with a total shared buried surface area of ~1879 Å2 (Fig. 2C). Consistent with earlier studies on intracellular E1E2 (43, 44), the interface interactions are non-covalent, comprising residues that mediate hydrophobic interactions or form hydrogen bonds. A highly conserved hydrophobic patch lines the E2 stem to stabilize the E1E2 heterodimer interface (Fig. 3 and fig. S5A). The E2 base contains a hydrophobic cavity involving residues F586, P590, F679, T681, L689, and I690, which interact with Y192, V194, Y201, and V203 on E1, whereas E655 and R659 form hydrogen bonds with L200 and G199 (Fig. 3A, i) (F, phenylalanine; I, isoleucine; L, leucine; P, proline; T, threonine; V, valine; Y, tyrosine). Within the hydrophobic stretch in the E2 stem, a region consisting of L654, Y701, and Y703 interacts with I308, Y309, P310, H312, V313, and M318 in E1 (Fig. 3A, ii and iv) and the stretch of residues Y703, V705, I709, and W716 pair with E1 residues V313, M318, S327, and I344 (Fig. 3A, iii) (H, histidine; M, methionine; S, serine; W, tryptophan).

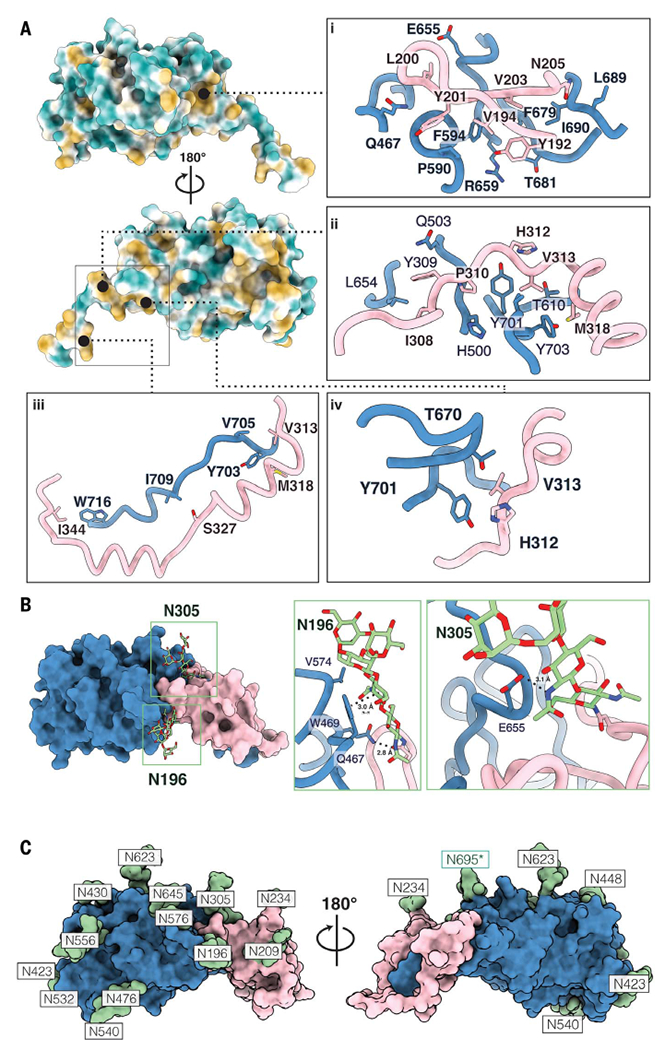

Fig. 3. The E1E2 interface and glycan shield.

(A) The newly characterized E1E2 interface is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions. E2 is colored by hydrophobicity, with green representing hydrophilic regions and yellow signifying hydrophobic patches. The first panel (i) showcases a deep hydrophobic cavity in the base of E2 against which E1 packs. The following panels (ii to iv) highlight additional hydrophobic interactions that we assert further stabilize the E1E2 interface. (B) Glycans buttress the E1E2 interface. Key interactions between glycans N196 and N305 are showcased. Glycan N196 is involved in hydrophobic interactions, including a π-π stacking interaction with W469, as well as a salt bridge with Q467. N305 forms a stabilizing salt bridge with E655. (C) Surface representation of the E1 and E2 model showing the glycan sites in green with their respective asparagine residues. The predominant glycoform identified by LC-MS at each PNGS was modeled using Coot (59). An asterisk indicates that the glycan at position N695 uses a noncanonical N-glycosylation motif, NXV. Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

The E1E2 interaction is further buttressed by two highly conserved glycans at N196 and N305 in E1 (Fig. 3B) (N, asparagine). The N305 glycan forms a salt bridge with E655 in E2, whereas the N196 glycan forms multiple interactions, including a salt bridge with Q467, π–π stacking interactions with the aromatic ring of W469, and hydrophobic packing interactions with V574 (Fig. 3B) (E, glutamate; Q, glutamine). To assess the relevance of this interface in infectivity, we measured viral entry of HCV pseudoparticles that contain amino acid mutations in the E1 NTD, E2 base, and E2 stem [Tyr201→Ala (Y201A), N205A, R659A, F679A, L689A, and Y703A; R, arginine] or glycan interface (N196 and/or N305: T198A, S307A, and T198A+S307A) (figs. S5A, and S6). Most viral mutants were noninfectious (<5% infectivity compared with wild type) except for T198A (~31% compared with wild type) (fig. S6). These data are consistent with and provide a structural basis for the results of a recent alanine scanning mutagenesis study on E1E2 pseudovirus (45), which also reported that amino acids R657, D658, L692, and Q700 in E2 and Y201, T204, N205, and D206 in E1 are crucial for infectivity (fig. S5, B to F) (D, aspartate).

The E1E2 glycan shield

All potential N-glycosylation sites (PNGSs) are located on one face of the E1E2 glycoprotein complex. The opposite face is hydrophobic and highly conserved (fig. S7A), consistent with an exposed neutralizing face subject to immune pressure and a non-neutralizing face that is likely inaccessible on the surface of the virion (22, 23, 46). We detected density for glycans at all PNGSs except N325 in E1, which is not glycosylated because of a proline at the fourth position within the N325 sequon (47)(fig. S7D). Interestingly, although N-glycans are usually located at NXT and NXS sequons, we also identified an N-glycan attached to a noncanonical NXV motif at N695 in E2 (Fig. 3C and fig. S7B) (X, any amino acid except for proline). Site-specific glycan analysis of the E1E2 heterodimer in complex with AR4A and AT1209 using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) confirmed the presence of glycans at all canonical PNGSs except N325, as well as at the noncanonical N695 site, which was glycan-occupied in 25% of the sample (Fig. 3C and fig. S7B). Further glycan analysis revealed that the occupancy of N695 remained unchanged when the E1E2 glycoprotein complex was not bound to AR4A and AT1209 Fabs (fig. S7, B and C). Additionally, the antigenicity of N695 mutants (N695A, N695Q, and V697T) was not substantially affected, whereas viral infectivity was slightly increased when the 695 glycan was removed (N695A and N695Q) (fig. S8, A and B). Moreover, the E1E2 heterodimer was highly enriched in oligomannose-type glycans (Man5-9GlcNAc2), except for N234 (fig. S7B). The oligomannose content is high likely because the transmembrane domain of E1 is a signal for static retention in the endoplasmic reticulum, where glycans remain oligomannose-type species, combined with purification from intracellular compartments, including the endoplasmic reticulum (48, 49).

Definition of three bNAb epitopes

Importantly, our full-length E1E2 structure delivers a structural description of three bNAb epitopes in their full quaternary context, including the previously ill-defined epitopes in AR4. Previous alanine-scanning mutagenesis studies suggested that AR4A recognizes an epitope on both E1 and E2 (28, 50). However, our model shows that AR4A targets the back layer and base regions of E2 but does not engage E1 (Fig. 4A). AR4A contacts E2 almost exclusively using its 25–amino acid–long CDRH3 through five hydrophobic interactions and four hydrogen bonds (AR4A - E2: T100c - G649, F100d - I696; L100e - D698, W646, P676; W100f - L667, Q671, I696) (Fig. 4A and figs. S9A and S12). AR4A contains a nine–amino acid insert in the CDRH2 (fig. S9), and this allows Y52i to electrostatically interact with R648 in the back layer of E2 (Fig. 4). Notably, one glycan in E2 (N623) interacts with the NTD of the light chain of the Fab (fig. S10A). Analysis of E1E2 glycoprotein mutants revealed that AR4A binding not only relied on direct amino acid contacts in E2 (R648 and D698) but was also affected by amino acid changes in the interface between E1 (Y201A, N205A, T198A, S307A, and T198A+S305A) and E2 (R659A, F679A, and L689A) (fig. S6, B and C). Moreover, the same mutants in a pseudovirus context were not infectious (fig. S6, A and C). Together, these data indicate that the epitope of AR4A on E2 is metastable and requires E1 for stable presentation (fig. S11). Hence, AR4A may neutralize the virus by stabilizing the prefusion state of E1E2 and impeding conformational changes needed for infection.

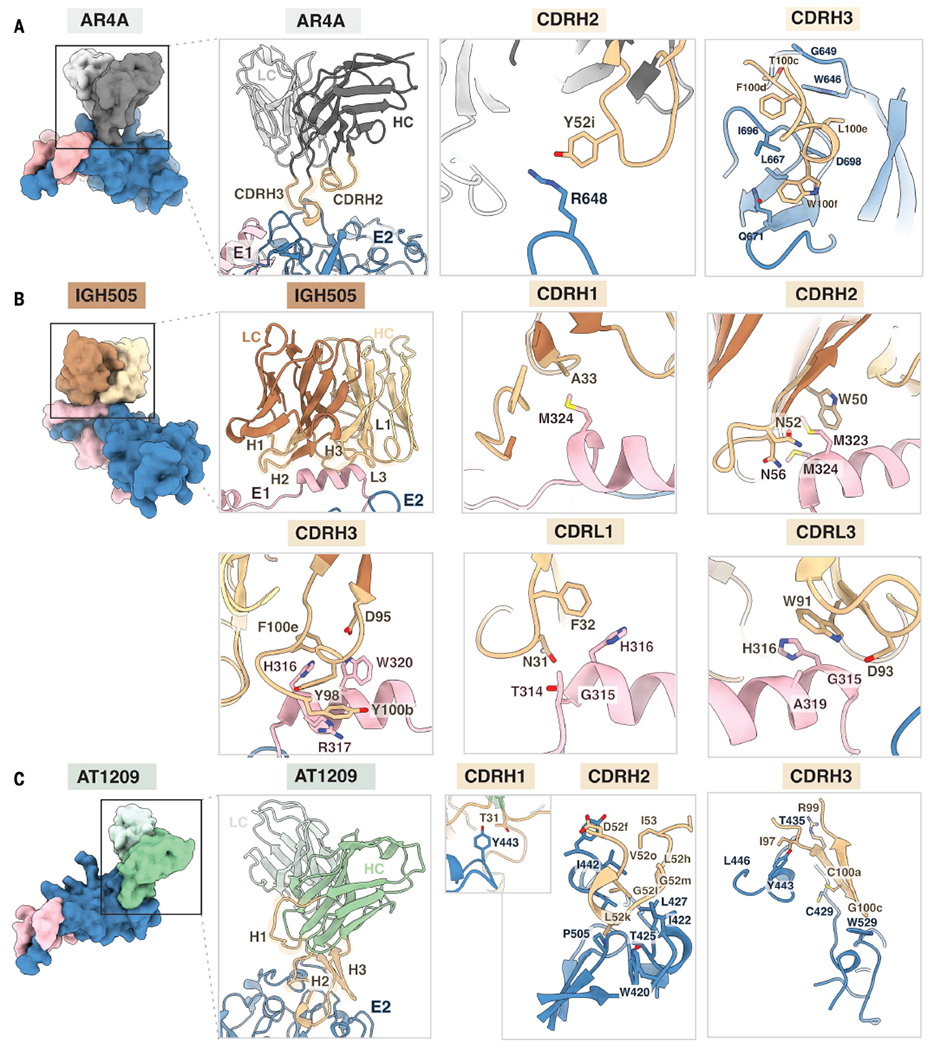

Fig. 4. Structural definition of the AR4A, IGH505, and AT1209 epitopes.

(A) The AR4A Fab recognizes protein elements in E2 (blue) near the interface with the E1 subunit (pink). Heavy and light chains are shown in dark and light gray, respectively, and CDRH2 and CDRH3 are highlighted in tan. Whereas the CDRH2 only interacts with the stem region of E2, the CDRH3 loop targets both the back layer and stem of E2. (B) The IGH505 Fab interacts with the surface-exposed α helix in E1 (pink). Heavy and light chains are shown in brown and yellow, respectively, and CDRH1 to CDRH3 and CDRL1 and CDRL3 are highlighted in tan. IGH505 encases the conserved α helix in E1 (amino acids 310 to 328) using the CDRH1 to CDRH3 and CDRL1 and CDRL3 regions of the Fab. (C) The AT1209 Fab binds the front layer of E2 (blue). Heavy and light chains are represented in green and light green, respectively, and CDRH1 to CDRH3 are highlighted in tan. All of the CDRH loops interact with the front layer of E2, near the CD81 binding site. Epitopes on E1 and E2 were defined as residues containing an atom within 4 Å of the bound Fab, and the amino acids present in the epitope are shown as sticks representations.

The bNAb IGH505 targets the surface-exposed conserved α helix in E1, which is positioned against the CDRH3 loop and inserted between the CDRH1, CDRH2, CDRL1, and CDRL3 loops with these five CDR loops making contact with the epitope (36). IGH505 targets H316 and W320 in E1, which bind to CDRH3, CDRL1, and CDRL3, likely through hydrogen bonds to D95 and π–π interactions with Y98, F100e (CDRH3), F32 (CDRL1), and W91 (CDRL3) (Fig. 4B and fig. S12). Also, M323 and M324, located at the C-terminal domain of the α helix in E1, are within hydrogen-bonding distance of A33 in CDRH1 and W50 and K58 in CDRH2 (K, lysine) (Fig. 4B and fig. S12). Although the latter interactions are not seen in the crystal structure of the E1 helix in complex with IGH526, both antibodies share similar footprints, indicating that they target an overlapping epitope at a very similar angle (figs. S9B and S10B) (27). Given the location of the IGH505 and IGH526 epitopes on E1, these antibodies likely neutralize the virus by impeding conformational changes of E1E2.

The bNAb AT1209 targets AR3, which involves the front layer and the CD81 binding loop in E2. AT1209 contains the longest CDRH3 loop among all known AR3-targeting bNAbs (25 amino acids) and shares a similar footprint with the previously described antibodies HEPC3, HEPC74, AR3C, AR3A, HC11, and AR3X (Fig. 4C and fig. S10C). The sequence signature of these VH1-69–derived bNAbs is a CDRH3 that contains a β hairpin–like structure stabilized by a disulfide bond (CXGGXC motif; G, glycine) (fig. S10D). The β-hairpin conformation adopted by the CDRH3 of AT1209 involves four hydrogen bond interactions between its CDRH3 and the front layer of E2 and the CD81 binding loop: I97-A248, R99-T435, C100a-C429, and G100c-W529 (Fig. 4C and figs. S10D and S12).

Although the CDRH3 dominates the paratope of most of the AR3-targeting bNAbs isolated to date, the unusually 32-residue-long CDRH2 (Kabat numbering) contributes substantially to the interaction of AT1209 with the front layer of E2, with nine residues within hydrogen-bonding distance (E52f, G52l, G52m, L52h, and I53) and burying similar surface area (493 Å2) to the CDRH3 (526 Å2) (Fig. 4C, figs. S10E and S12, and table S2). A similarly ultralong CDRH2 (31 residues) is present in AR3X (21). Additionally, functional and structural analyses reveal that the amino acids that are critical for host receptor CD81 engagement by E2 (I422, S424, L427, N430, S432, G436, W437, L438, G440, L441, F442, Y443, V515, T519, T526, Y527, W529, and W616) overlap with those located in the epitope of the AT1209 antibody (fig. S13). Collectively, these data give us comprehensive insights into the neutralizing face of E1 and E2 and facilitate structure-based vaccine design (fig. S14).

Discussion

The structure of the HCV envelope glycoprotein complex E1E2 proved challenging to resolve because of the need to coexpress E1 and E2 and their propensity to form heterogeneous complexes (29, 51–53). Previous studies showed that the E1E2 glycoprotein complex is a non-covalent heterodimer in infected cells and that it selectively forms disulfide-linked complexes on virions (48). Whether these disulfide-linked complexes present infectious E1E2 or misfolded noninfectious forms is unknown at the present time. Interestingly, a previous study showed that the neutralizing antibody AR4A only captures a small fraction of available virions (13), suggesting that a substantial portion of virion-associated E1E2 might be nonfunctional. Our studies demonstrate that the E1E2 interface is stabilized by glycans and hydrophobic patches as opposed to covalent disulfide bonds, providing insight into how to engineer stable immunogens for structure-based vaccine design (54–56).

Coexpression of the bNAb AR4A was key to stabilizing the metastable E1E2 complex, which we surmise is arrested in the prefusion conformation. Similarly, structures of prefusion HIV-1 Env and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F were solved using conformational prefusion-specific antibodies (54, 57). The viral entry pathway after CD81 binding likely involves a multistep process in which the interface of the E1E2 glycoprotein complex is destabilized and opens up upon low pH and/or receptor binding, triggering downstream conformational changes that expose the fusion peptide on E1 and induce viral fusion (24, 45). Neutralizing antibodies can therefore either block CD81 binding by direct competition—for example, AT1209—or, if bound outside the receptor binding site, can impede entry by blocking conformational changes required for fusion, for example, AR4A and IGH505.

Our cryo-EM structure elucidates the HCV E1E2 glycan shield that includes a rare glycan addition to a noncanonical NXV sequon at position 695. This glycan did not have a substantial impact on E1E2 function in vitro. However, it may have a role in vivo, for example, by creating additional heterogeneity and/or by shielding underlying protein epitopes. Where glycans usually play minor roles in the stability between interfaces in protein complexes, two glycans are critical for stabilizing the E1E2 interface. The E1E2 region that lacks glycans is primarily hydrophobic and therefore may be involved in oligomerization and/or interaction with the viral lipid bilayer (58). Overall, our cryo-EM study elucidates a full molecular description of E1E2, including three bNAb epitopes, and provides a long-sought-after blueprint for the design of a new generation of HCV glycoprotein immunogens and antiviral drugs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Anderson, H. L. Turner, and M. Wu for cryo-EM data collection support; C. Bowman and J. C. Ducom for computational support; and A. Antanasijevic, G. Ozorowski, P. Sauer, D. Montiel-Garcia, E. Watson, B. Basanta, and J. Yang for supportive discussions. We thank J. Koopsen for the sequence alignment used for generating fig. S5A, N. Zandhuis for performing pilot experiments on AR4A coexpression, and M. J. van Gils for supervising HCVpp assays. We also acknowledge the Scripps Research Institute CryoEM Facility and additional scientific resources at the Scripps Research Institute. We thank S. Foung for donating the 212.10 and 212.15 antibodies and T. Beaumont and S. Merat for donating the AT1209 and AT1618 antibodies and antibody plasmids. We also thank V. Eshun-Wilson for grammar and editing expertise.

Funding:

R.W.S. is a recipient of a Vici grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). J.S. is a recipient of a Vidi and Aspasia grant from the NWO (grant numbers 91719372 and 015.015.042). This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant 2109312 to L.E.-W., NWO Rubicon grant 45219118 to A.T.d.l.P., and an Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity Postdoctoral grant to K.S. Mass spectrometry was supported by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant INV-008352/OPP1153692 to M.C. M.C. is a supernumerary fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, and professor adjunct at the Scripps Research Institute, CA. G.C.L. is supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants GM143805 and GM142196.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

The GenBank entry for AMS0232 is OL855837.1. The PDB IDs and Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) IDs for the E1E2 maps have been deposited into the RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org) under accession number 7T6X and to the EMDB database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/) under the accession number EMD-25730. The EMDB for the NS-EM map has been deposited into the EMDB database under the accession number EMD-27578. The mass spectrometry RAW files have been deposited in the MassIVE server (https://massive.ucsd.edu) with accession number (MSV000088553). Materials are available from A.B.W. or R.W.S. upon request.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fuerst TR, Pierce BG, Keck ZY, Foung SKH, Front. Microbiol 8, 2692 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yost SA, Wang Y, Marcotrigiano J, Front. Immunol 9, 1917 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinchen VJ et al. Cell Host Microbe 24, 717–730.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pestka JM et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 104, 6025–6030 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merat SJ et al. J. Hepatol 71, 14–24 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law M et al. Nat. Med 14, 25–27 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Shea D et al. Liver Transpl. 22, 324–332 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jong YP et al. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 254ra129 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenbach BD, Rice CM, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 11, 688–700 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pileri P et al. Science 282, 938–941 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarselli E et al. EMBO J. 21, 5017–5025 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drummer HE, Boo I, Poumbourios P, J. Gen. Virol 88, 1144–1148 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catanese MT et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 9505–9510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieyres G, Dubuisson J, Pietschmann T, Viruses 6, 1149–1187 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stejskal L et al. PLOS Comput. Biol 16, e1007710 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavie M, Hanoulle X, Dubuisson J, Front. Immunol 9, 910 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goffard A et al. J. Virol 79, 8400–8409 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentoe J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116, 10039–10047 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong L et al. Science 342, 1090–1094 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan I et al. J. Virol 88, 12276–12295 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flyak AI et al. Cell Host Microbe 24, 703–716.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzarum N et al. Sci. Adv 5, eaav1882 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzarum N, Wilson IA, Law M, Front. Immunol 9, 1315 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A et al. Nature 598, 521–525 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Omari K et al. Nat. Commun 5, 4874 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter JA et al. J. Virol 86, 12923–12932 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong L et al. J. Mol. Biol 427, 2617–2628 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giang E et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 6205–6210 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruwona TB, Giang E, Nieusma T, Law M, J. Virol 88, 10459–10471 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao L et al. PLOS Pathog. 15, e1007759 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guest JD et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 118, e2015149118 (2021).33431677 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas XV et al. AIDS 29, 2287–2295 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierce BG et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, E6946–E6954 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merat SJ et al. PLOS ONE 11, e0165047 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson ML et al. eLife 7, e34085 (2018).30109849 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meunier JC et al. J. Virol 82, 966–973 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer W et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 11187–11192 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Punjani A, Fleet DJ, J. Struct. Biol 213, 107702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castelli M et al. Drug Discov. Today 19, 1964–1970 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wahid A et al. J. Virol 87, 1605–1617 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krey T et al. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1000762 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marín MQ et al. Vaccines 8, 440 (2020).32764419 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W et al. Virology 448, 229–237 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deleersnyder V et al. J. Virol 71, 697–704 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfaff-Kilgore JM et al. Cell Rep. 39, 110859 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Lorenzo C, Angus AGN, Patel AH, Viruses 3, 2280–2300 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meunier JC et al. J. Gen. Virol 80, 887–896 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vieyres G et al. J. Virol 84, 10159–10168 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cocquerel L et al. J. Virol 73, 2641–2649 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gopal R et al. PLOS Pathog. 13, e1006735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michalak JP et al. J. Gen. Virol 78, 2299–2306 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel J, Patel AH, McLauchlan J, Virology 279, 58–68 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brazzoli M et al. Virology 332, 438–453 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLellan JS et al. Science 340, 1113–1117 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Taeye SW et al. Cell 163, 1702–1715 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juraszek J et al. Nat. Commun 12, 244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JH, Ozorowski G, Ward AB, Science 351, 1043–1048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Falson P et al. J. Virol 89, 10333–10346 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emsley P, Crispin M, Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 256–263 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GenBank entry for AMS0232 is OL855837.1. The PDB IDs and Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) IDs for the E1E2 maps have been deposited into the RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org) under accession number 7T6X and to the EMDB database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/) under the accession number EMD-25730. The EMDB for the NS-EM map has been deposited into the EMDB database under the accession number EMD-27578. The mass spectrometry RAW files have been deposited in the MassIVE server (https://massive.ucsd.edu) with accession number (MSV000088553). Materials are available from A.B.W. or R.W.S. upon request.