Abstract

Background

Adenoid ameloblastoma (AdAM) is a frequently recurrent tumor that shows hybrid histological features of both ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT). AdAM is expected to be classified as a new subtype of ameloblastoma in the next revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) odontogenic tumor classification. However, whether AdAM is a histologic variant of ameloblastoma or AOT remains unclear. To establish a new category, genetic evidence indicating the tumor category is necessary.

Methods

We present a case of a 23-year-old Japanese woman with AdAM who underwent genetic/DNA analysis for ameloblastoma-related mutation using immunohistochemical staining, Sanger sequencing, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses with reliable clinicopathological evidence.

Results

Immunohistochemical expression of BRAF p.V600E was diffusely positive for both ameloblastoma- and AOT-like components. Sanger sequencing and NGS analyses showed missense mutations in BRAF p.V600E (c.1799T > A), a gene that is commonly altered in ameloblastomas but not in KRAS, another gene associated with AOT.

Conclusion

This case report is the first to provide genetic evidence on the ameloblastomatous origin of AdAM with a BRAF p.V600E mutation. A larger series of AdAM groups’ molecular testing is needed to aptly classify them and prognosticate the best treatment.

Keywords: Adenoid ameloblastoma, Next-generation sequencing, Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, BRAF p.V600E, KRAS

Introduction

Adenoid ameloblastoma (AdAM) is a unique type of tumor that shows hybrid histological features of both ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) but has higher recurrence rate than ameloblastoma and AOT [1, 2]. The latest WHO odontogenic tumor classification indicated that AdAM might be included in the subtype of ameloblastoma in revised version [2]. However, genetic mutation usually identified in ameloblastoma, have not been previously detected in AdAM [1–3]. Therefore, it remained unclear whether AdAM is a unique standalone tumor or a histologic variant of ameloblastoma or AOT. In order to establish a new category, make an accurate diagnosis, and improve therapeutic management, genetic evidence for AdAM indicating the tumor category is necessary.

Case Presentation

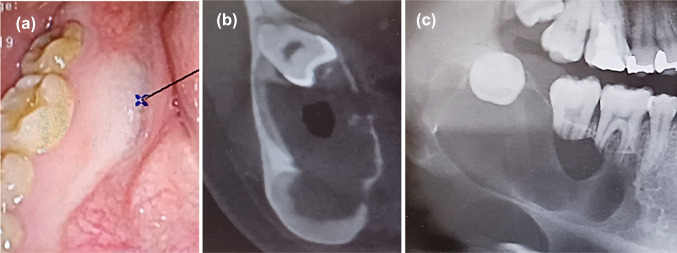

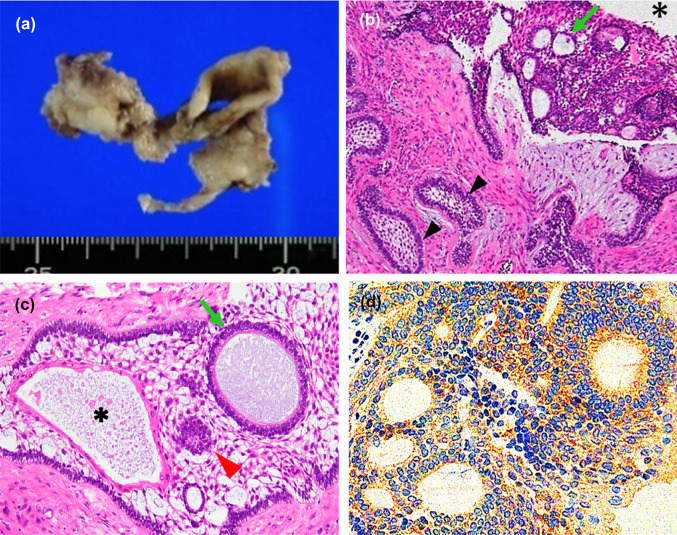

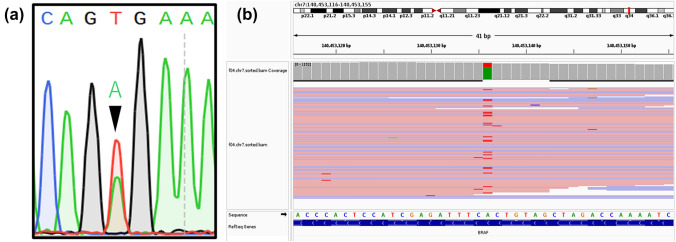

A 23-year-old Japanese woman presented with a right submandibular painless mass, mental nerve palsy, and numbness 1 year prior to admission. Intraoral examination revealed a swollen mass at the mandibular first to third molar region covered by white to red gingival mucosa (Fig. 1a). Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a multi-lobulated mass on the right side with extensive destruction of the angle of the mandible (Fig. 1b). Panoramic CT revealed an ill-defined mass in the right mandibular bone involving an impacted third molar and the roots of the first and second molars (Fig. 1c). The lesion was diagnosed as ameloblastoma after performing biopsy and enucleated. Macroscopically, the tumor appeared as a white solid cystic mass (Fig. 2a). Histologically, the tumor showed a cystic space and plexiform to solid nests infiltrating the surrounding tissues (Fig. 2b). The cyst walls and nests consisted of satellite-like, polygonal, clear cells lined by columnar cells and included some gland-like structures, epithelial whorls, and microcytic spaces lined by eosinophilic cells showing squamous metaplasia (Fig. 2c). The gland-like structures included myxoid to eosinophilic materials and were lined by columnar epithelium, with the nuclei tending to be displaced away from the lumen (Fig. 2c). The connective tissues showed deposition of some immature dentinoid material. No cell atypia or mitosis was observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor nest was diffusely positive for BRAF p.V600E, CK14, and CK19, while the palisading cells at the peripheral nest were positive for podoplanin (Fig. 2d). Moreover, p53 was not overexpressed, and the Ki-67 index was 10%. Additionally, Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses using cancer hotspot panel v2 revealed missense mutations in BRAF p.V600E (c.1799 T > A), a gene that is commonly altered in ameloblastomas, but not in KRAS, genetic alterations of which are associated with AOT (Fig. 3a and b). Therefore, the patient was re-diagnosed with AdAM. Mental nerve palsy still persisted six months after surgery. However, radiological imaging showed absence of disease recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Intraoral examination showing a swelling mass in the first to third molar region of the mandibular bone covered by white to red gingival mucosa (a). Computed tomography imaging showing the thinning of the lingual border of the right mandible due to tumor growth (b). Panoramic computed tomography showing an ill-defined lobulated mass showing resorbed roots of the first and second molars and impacted right third molar (c)

Fig. 2.

White solid cystic mass (a). Tumor with cystic space (*) and plexiform to solid nests including gland-like structures (b arrowhead, follicular nest; arrows, gland-like structures; H&E × 10). Gland-like structures (arrows), epithelial whorls (arrowhead), and microcytic spaces lined by squamous metaplastic cells (*) were observed in the nest comprising satellite-like polygonal cells (c H&E × 10). Immunohistochemical staining showing diffusely positive BRAF p.V600E (d × 10). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin

Fig. 3.

Sanger sequencing (a) and next-generation sequencing (b) revealing BRAF p.V600E mutation (c.1799 T > A). The green-labeled “A” nucleotides are from AdAM, while the red-labeled “T” nucleotides are from the non-tumor components

Discussion

Although 40 cases of AdAM have been reported, mutations of odontogenic origin have not yet been detected [1–3]. To the best of our knowledge, this case report is the first to present the molecular aspects of AdAM supported by genetic and clinicopathologic evidence.

Genetically, majority of ameloblastomas exhibit BRAF p.V600E (maxilla, 20%; mandible, 72%) and SMO L412F (maxilla, 55%; mandible, 5%) mutations, while AOT exhibits KRAS codon 12 (p.G12V or p.G12R) mutation [1–4]. Our patient showed presence of BRAF p.V600E mutation on Sanger sequencing and NGS, but KRAS mutations were not detected. In the present case report, the DNA and RNA were extracted from non-decalcified formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded materials, preserving the quality of the nucleic acid. Moreover, various NGS techniques, which are more sensitive than Sanger sequencing [5], were also employed, instead of using Sanger sequencing alone as in previous studies [3, 5]. Thus, this case report provides reliable genetic evidence on the ameloblastomatous origin of AdAM.

Clinically, AdAMs occur in the posterior jaw (35.3%) and mandible (64.7%) in middle age (range 15–82 years, mean 39 years, male:female proportion = 0.9:1). Patients usually complain of swelling followed by paranesthesia and numbness [6]. Radiologically, AdAM appears as an ill-defined radiolucent lesion with recurrence rates ranging from 45.4 to 70%, which are higher than those of ameloblastoma (12% to 35%). Currently, AdAM is recognized as a new frequently recurrent subtype of ameloblastoma [1, 2, 7–9]. Our case fits nicely within the spectrum of AdAM as it appears in the most recent WHO classification. Although the differential diagnosis includes AOT, it typically occurs in the maxillary cuspids of teenage females and is usually self-limited [4, 10].

Histologically, AdAMs may show overlapping features associated with both ameloblastoma and AOT [1, 2], such as a satellite reticulum-like nest similar to traditional ameloblastoma and dentinoid deposition (100%), glandular structures (95.9%), epithelial whorls (29.2%), and rosettes (12.5%) [1]. Squamous metaplasia and ghost cell differentiation are also observed [6, 11].

Immunohistochemically, AdAM is diffusely positive for CK14 and CK19, indicating odontogenic and ameloblastic differentiation [11]. Although the immunohistochemical expression of BRAF p.V600E and podoplanin had not been examined in AdAM, BRAF p.V600E [VE1], also evaluated in the present case, was highly specific in odontogenic tumor with BRAF p.V600E mutation but not in AOT [12, 13]. Podoplanin was observed in the peripheral cells of conventional ameloblastoma and gland structures of AOT [14, 15]. These features are consistent with that of the present case and suggested an ameloblastic origin with glandular differentiation. Moreover, AdAM does not demonstrate overexpression of p53 but shows a variable Ki-67 index [6, 11]. Notably, the present case might have an aggressive potential as the Ki-67 index (10%) was slightly higher than that of conventional AOT (1%) and ameloblastoma (4%) [16].

To diagnose AdAM, three histological criteria are required: (1) at least one feature of ameloblastoma, such as any subtype and satellite reticulum-like cells; (2) at least one feature of AOT, such as duct-like structures, glandular differentiation, or epithelial whorls; and (3) presence of dentinoid in the mature fibrous stroma [1]. The present case fulfilled all three criteria. The differential histological diagnosis was odontogenic tumors with BRAF p.V600E mutation such as ameloblastoma, ameloblastic-fibroma, ameloblastic-fibro-odontoma, and a hybrid tumor composed of ameloblastoma and AOT. Ameloblastoma, ameloblastic-fibroma, and ameloblastic-fibro-odontoma show absence of glandular structures. BRAF p.V600E was diffusely positive even in the AOT-like component, which was the same as that in the ameloblastoma-like component; this finding indicated that the present case was not a hybrid tumor as the mutation was part of the process of tumor formation. Thus, these clinicopathological features supported the diagnosis of AdAM in addition to the genetic evidence.

An independent classification of AdAM has not been made; thus, it is not well recognized, and no standard strategy for treatment has been established. For local AdAM, a more aggressive treatment might be required, such as wide excision, compared with that used for ameloblastoma and AOT [1, 2]. Neoadjuvant anti-BRAF targeted therapy remains the novel treatment for ameloblastoma [17]. Using BRAF inhibitor for AdAM with BRAF p.V600E mutation could help preserve the maxillofacial functions and improve the patients’ outcome. Thus, recognizing AdAM is crucial for its accurate diagnosis and better therapeutic management. Some cases of AdAM, especially in the mandibular molar region similar to the present case, may be reported as a unicystic ameloblastoma associated with AOT or follicular AOT [1, 18]. Therefore, in the revised version of the WHO odontogenic tumor classification [2], AdAM should be categorized as an aggressive subtype of ameloblastoma.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this case report is the first to provide genetic evidence that AdAM is in line with other reported ameloblastomas, particularly associated with the BRAF p.V600E mutation. Given our report, with classic AdAM morphology and diffuse expression of BRAF p.V600E among architectural patterns, a review of a larger series of these tumors to affirm the genetic basis for neoplasia will be needed, along with clinical features, to best classify these tumors and ultimately develop adequate treatment protocols and follow-up strategy.

Author Contributions

YN, KH and KT diagnosed the patient reported in this case study. SS, TS and YK treated the patient clinically.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Consent for publication was obtained for ORCAD every individual person’s data included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jayasooriya PR, Abeyasinghe WAMUL, Liyanage RLPR, Uthpali GN, Tilakaratne WM. Diagnostic enigma of adenoid ameloblastoma: literature review based evidence to consider it as a new subtype of ameloblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16:344–352. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01358-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vered MA, John MW. Update from the 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumours. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;1:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01404-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coura BP, Dos Santos JN, Fonseca FP, et al. Adenoid ameloblastoma with dentinoid is molecularly different from ameloblastomas and adenomatoid odontogenic tumors. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;50:1067–1071. doi: 10.1111/jop.132434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Naggar CJKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg P (2017) Odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumours. In: Name of editor (ed) WHO classification of head and neck tumours, 4th edn. IARC, Lyon

- 5.Almomani R, Marchi M, Sopacua M, et al. Evaluation of molecular inversion probe versus TruSeq® custom methods for targeted next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0238467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachdev SS, Chettiankandy TJ, Sardar MA, Adhane Y, Shah AM, Grace AE. Adenoid ameloblastoma with dentinoid: a systematic review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2022;22:325–338. doi: 10.18295/squmj.9.2021.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiao X, Shi J, Liu J, Liu J, Guo Y, Zhong M. Recurrence rates of intraosseous ameloblastoma cases with conservative or aggressive treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:647200. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.647200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hresko A, Palyvoda R, Burtyn O, et al. Recurrent ameloblastoma: clinical manifestation and disease-free survival rate. J Oncol. 2022;2022:2148086. doi: 10.1155/2022/2148086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loyola AM, Cardoso SV, de Faria PR, et al. Adenoid ameloblastoma: clinicopathologic description of five cases and systematic review of the current knowledge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2015;120:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siriwardena BS, Udagama MN, Tennakoon TM, Athukorala DA, Jayasooriya PR, Tilakaratne WM. Clinical and demographic characteristics of adenomatoid odontogenic tumors: analysis of 116 new cases from a single center. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;88:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adorno-Farias D, Muniz VR, Soares AP, et al. Ameloblastoma with adenoid features: a series of eight cases. Acta Histochem. 2018;120:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo E, Khalili P, Beuhler K, Siddiqi I, Vasef MA. BRAF V600E mutation across multiple tumor types: correlation between DNA-based sequencing and mutation-specific immunohistochemistry. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018;26:709–713. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh KY, Cho SD, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Hong SD. Discrepancy between immunohistochemistry and sequencing for BRAF V600E in odontogenic tumours: comparative analysis of two VE1 antibodies. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;50:85–91. doi: 10.1111/jop.13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhal N, Khanduri N, Kurup D, Gupta B, Mitra P, Chawla R. Immunohistochemical evaluation of podoplanin in odontogenic tumours & cysts using anti-human podoplanin antibody. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2017;7:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Khongkhunthian P, Sciubba JJ. Immunoprofile of the adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Oral Dis. 2017;23:731–736. doi: 10.1111/odi.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razavi SM, Tabatabaie SH, Hoseini ST, Hoseini ET, Khabasian A. A comparative immunohistochemical study of Ki-67 and Bcl-2 expression in solid ameloblastoma and adenoid odontogenic tumor. Dent Res J. 2012;9:192–197. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.95235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschhorn A, Campino GA, Vered M, et al. Upfront rational therapy in BRAF V600E mutated pediatric ameloblastoma promotes ad integrum mandibular regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;15:1155–1161. doi: 10.1002/term.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raubenheimer EJ, van Heerden WF, Noffke CE. Infrequent clinicopathological findings in 108 ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.