Summary

Background

Patients established on thiopurines (e.g., azathioprine) are recommended to undergo three-monthly blood tests for the early detection of blood, liver, or kidney toxicity. These side-effects are uncommon during long-term treatment. We developed a prognostic model that could be used to inform risk-stratified decisions on frequency of monitoring blood-tests during long-term thiopurine treatment, and, performed health-economic evaluation of alternate monitoring intervals.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study set in the UK primary-care. Data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink Aurum and Gold formed development and validation cohorts, respectively. People age ≥18 years, diagnosed with an immune mediated inflammatory disease, prescribed thiopurine by their general practitioner for at-least six-months between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2019 were eligible. The outcome was thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal blood-test results. Patients were followed up from six-months after first primary-care thiopurine prescription to up to five-years. Penalised Cox regression developed the risk equation. Multiple imputation handled missing predictor data. Calibration and discrimination assessed model performance. A mathematical model evaluated costs and quality-adjusted life years associated with lengthening the interval between blood-tests.

Findings

Data from 5982 (405 events over 16,117 person-years) and 3573 (269 events over 9075 person-years) participants were included in the development and validation cohorts, respectively. Fourteen candidate predictors (21 parameters) were included. The optimism adjusted R2 and Royston D statistic in development data were 0.11 and 0.76, respectively. The calibration slope and Royston D statistic (95% Confidence Interval) in the validation data were 1.10 (0.84–1.36) and 0.72 (0.52–0.92), respectively. A 2-year period between monitoring blood-test was most cost-effective in all deciles of predicted risk but the gain between monitoring annually or biennially reduced in higher risk deciles.

Interpretation

This prognostic model requires information that is readily available during routine clinical care and may be used to risk-stratify blood-test monitoring for thiopurine toxicity. These findings should be considered by specialist societies when recommending blood monitoring during thiopurine prescription to bring about sustainable and equitable change in clinical practice.

Funding

National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Thiopurine, Drug toxicity prediction

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Patients established on a thiopurine (e.g., azathioprine) are recommended to undergo three-monthly monitoring blood tests for the early detection of blood, liver, or kidney toxicity even though these side-effects are uncommon during long-term treatment. Our review of research indexed in the PubMed between 1st January 1995 and 31st December 2022 using search terms: thiopurine AND monitoring AND cost-effective without any restrictions on language and study-design did not find any study that evaluated the effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness of blood-test monitoring stratified according to the individuals’ risk of toxicity during long-term thiopurine treatment.

Added value of this study

In this study we set out to find whether the risk of clinically significant liver, blood, or kidney toxicity during established thiopurine treatment can be predicted and the interval between monitoring blood-tests be increased cost-effectively. We found that in adults with a broad range of immune mediated inflammatory diseases, a prognostic model that included demographic and clinical features that are easily ascertained during clinic visits, predicted clinically-significant blood-test abnormalities with high calibration and discrimination. The model performance was comparable across age groups and in people with inflammatory bowel disease. It was also cost-effective to increase the interval between monitoring blood-tests.

Implications of all the available evidence

Patients and health professionals may decide the interval between monitoring blood-tests during long-term thiopurine treatment using this easy-to-use prediction model. Health policy makers may use the risk scores alongside the cost-effectiveness estimates to recommend the risk threshold at which the intervals between monitoring blood-tests may be increased. Future research is required to ascertain whether the addition of results of thiopurine methyl transferase testing and thiopurine therapeutic drug monitoring metabolites to the model would improve its performance.

Introduction

Thiopurines are a cornerstone glucocorticoid sparing drug for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), widely recommended globally for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD).1, 2, 3, 4 They are among first-line glucocorticoid sparing drugs for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and are used in the management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriasis ± arthritis.5,6 The usual recommended dose for the management of IBD and other inflammatory conditions is azathioprine 2.0–2.5 mg/kg/day, and 1.0–3.0 mg/kg/day, respectively, although lower doses may be effective.

Thiopurines can cause myelotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and, nephrotoxicity, mostly during the first few months of treatment, and dose-reduction is considered in severe renal impairment.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Concern about these issues led to recommendations to undertake two to four weekly monitoring blood-tests during the first few months of treatment followed by testing at three monthly intervals thereafter.4,6,13 Frequent monitoring blood-tests within the first few months of treatment are important due to the high risk of reversible target organ damage in this period. However, regular monitoring blood-tests during established long-term thiopurine treatment, a period when blood-test abnormalities are uncommon, seems unduly cautious and unnecessary. Whether routinely available clinical data can be used to ascertain those at low, medium, or high risk of toxicity in this period, and be used to inform risk-stratified monitoring has not been evaluated.

Avoidable testing is a wasteful use of healthcare resources. It would be beneficial to predict those at high risk of toxicity during long-term thiopurine treatment who continue to need monitoring at the current frequency while others have less frequent monitoring blood-tests. In order to inform such risk-stratified monitoring, we developed and validated a prognostic model for clinically-significant thiopurine toxicity detectable on monitoring blood-tests. We also undertook health economic analysis to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of different monitoring intervals.

Methods

Study setting

Data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Aurum and Gold were used for model development and validation, respectively.14,15 CPRD is an anonymised longitudinal database of electronic health records from primary care in the National Health Service. This study was approved by CPRD’s Research Data Governance (protocol: 20_000236R), which has overarching research ethics committee approval for studies using anonymous data (reference 05/MRE04/87). Practices that contributed data to the CPRD consented to using anonymized patient data for approved research projects and additional consent was not required prior to individual studies.

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective cohort study. Adults (age ≥18 years), newly diagnosed with either IBD, SLE, RA, psoriasis ± arthritis, or axial spondyloarthropathy between 01/01/2007 and 12/31/2019 and prescribed thiopurine (either azathioprine or mercaptopurine) by their general-practitioner for at-least six months were included. Additionally, they were required to have ≥1-year inflammatory disease-free registration at their general-practice to be considered as being newly diagnosed,16,17 and to receive their first thiopurine prescription either after this diagnosis or within the preceding 90-days to allow for recording of diagnoses lagging behind prescriptions. We did not include thioguanine in this study as it is rarely used to treat inflammatory conditions. Its use is restricted to specialist centres for the treatment of refractory IBD and it is not prescribed from primary care. In the UK, it is licenced for the treatment of acute or chronic myeloid leukaemia.

Patients with either severe chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4 or 5, or severe haematological disease prior to start of follow-up were excluded as the former two are relative contraindications for thiopurine and inclusion of severe haematological diseases would have caused uncertainty in outcome ascertainment. Any general-practices that contributed data to both CPRD Aurum and Gold were excluded from the development cohort using a bridging file provided by the CPRD.

In the UK, thiopurine initiation and initial monitoring are led by hospital out-patient clinics. Once disease control is achieved with a stable thiopurine dose, usually four to six months after treatment initiation, the responsibility for prescribing and monitoring is handed to the patients’ general practitioner (GP).18, 19, 20 During shared-care prescribing all treatment changes including for abnormal blood-test results are directed by the hospital specialist.

We followed-up patients from 180-days after the first primary-care thiopurine prescription until the earliest date of outcome, death, transfer out of practice, 90-day prescription gap, last data collection from practice, 31/12/2019 or five-years. Thiopurine-toxicity associated drug discontinuation defined as a prescription gap of ≥90 days with either an abnormal blood-test result or a diagnostic code within ±60 days of the last prescription date was the outcome of interest.21 The threshold for abnormal blood-test results were: total leucocyte count <3.5 × 109/l; neutrophil count <1.6 × 109/l; platelet count <140 × 109/l; ALT/AST >100 IU/ml; and kidney function decline defined as either CKD progression based on medical codes recorded by the GP, or a creatinine increase of >26 μmol/l, the threshold for consideration of acute kidney injury.18,22

Predictors were defined based on the latest record within 2 years of the start of follow-up except for prescriptions which were defined using the prior 6-months’ primary-care prescriptions. These were selected by clinical members of the team (Table 1). Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), alcohol intake, and, diabetes were included as they associate with drug induced liver injury.23 Smoking was included as it associates with active RA, CD, and, SLE that may require the use of higher thiopurine doses.24, 25, 26 CKD was included as it reduces thiopurine clearance.27 The mercaptopurine equivalent dose was included in the model as thiopurine toxicity is dose dependent.28,29 Statins and ACE inhibitors were included as their use is associated with target organ thiopurine toxicity.12 Allopurinol was included as it inhibits thiopurine metabolism by inhibiting xanthine oxidase and co-prescription can cause cytopenia if the dose of thiopurine is not reduced substantially e.g., to 25% of the regular dose.12 Additionally, low-dose allopurinol may be combined with low-dose azathioprine in patients with prior thiopurine induced hepatotoxicity to minimise the future risk of hepatotoxicity and myelotoxicity in hyper-methylators and this approach was shown to have greater likelihood of achieving remission in a clinical trial.30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA) and other immune-suppressing drugs were included as they can cause cytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, and, acute kidney injury. Additionally, 5-ASA drugs are associated with thiopurine induced myelotoxicity as they increase 6-thioguanine nucleotide (6-TGN) levels.35,36 Either cytopenia (neutrophil count <2 × 109/l, total leucocyte count <4 × 109/l, or platelet count <150 × 109/l) or elevated transaminase (ALT and/or AST >35 IU/l) during the first six months of primary-care prescription were included as they predicted cytopenia and/or transaminitis in other studies.37,38

Table 1.

Distribution of candidate predictors in development and validation cohorts.

| Predictora | Development cohort (CPRD Aurum) n = 5982 |

Validation cohort (CPRD Gold) n = 3573 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (standard deviation) year | 42 (17) | 43 (17) |

| Male sex | 2940 (49.1) | 1775 (49.7) |

| Female sex | 3042 (50.9) | 1798 (50.3) |

| Mercaptopurine equivalent dose (mg/day), median (IQR) | 48.1 (36.1, 72.1) | 48.1 (24.0, 72.1) |

| Missing | 627 (10.5) | 830 (23.2) |

| Body mass index | ||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 276 (4.6) | 136 (3.8) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 2178 (36.4) | 1274 (35.7) |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 1562 (26.1) | 955 (26.7) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 1155 (19.3) | 699 (19.6) |

| Missing | 811 (13.6) | 509 (14.3) |

| Current smoker | ||

| Nob | 5000 (83.6) | 2906 (81.3) |

| Yes | 982 (16.4) | 667 (18.7) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Non-user | 1106 (18.5) | 502 (14.1) |

| Low (1–14 units/week) | 2273 (38.0) | 1694 (47.4) |

| Moderate (15–21 units/week) | 293 (4.9) | 171 (4.8) |

| Hazardous (>21 units/week) | 374 (6.3) | 189 (5.3) |

| Ex-user | 500 (8.4) | 211 (5.9) |

| Missing | 1436 (24.0) | 806 (22.3) |

| Inflammatory conditions | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 5317 (88.9) | 3219 (90.1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 230 (3.8) | 130 (3.6) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 243 (4.1) | 109 (3.1) |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathyc | 192 (3.2) | 115 (3.2) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 457 (7.6) | 240 (6.7) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease stage-3d | 249 (4.2) | 148 (4.1) |

| Drugs | ||

| 5-aminosalicylatese | 2766 (46.2) | 1730 (48.4) |

| Sulfasalazine | 74 (1.2) | 47 (1.3) |

| Methotrexate/Leflunomide | 13 (0.2) | 17 (0.5) |

| Statins | 645 (10.8) | 398 (11.1) |

| Allopurinol | 160 (2.7) | 64 (1.8) |

| ACE inhibitors | 486 (8.1) | 280 (7.8) |

| At least mild cytopenia or liver enzyme elevation in six-months preceding start of follow-up | 785 (13.1) | 529 (14.8) |

| Number (%) of outcome events | 405 (6.8) | 269 (7.5) |

Values are numbers (percentage) unless stated otherwise.

Included non-smokers, ex-smokers, and smoking status not-available.

Seronegative spondarthritis included psoriasis (±arthritis), ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis.

Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease stages 4 and 5 were excluded from this study.

Included balsalazide, mesalazine, olsalazine.

Sample size

For model development, assuming an event rate of 17 per 1000-person years from previously published studies and an average follow-up of 3.19 years, the minimum sample size needed to minimise model overfitting (a target shrinkage factor of 0.9) and ensure precise estimation of overall risk was 1748 participants (95 outcomes) for a maximum of 25 parameters, Cox-Snell R2 value of 0.12, a 5-year time horizon, using the formulae of Riley et al.39,40 The sample size for external model validation was much larger than the typically recommended minimum sample size of 200 events.

Statistical analysis

Multiple imputation handled missing predictor data on BMI, alcohol intake, and, thiopurine dose using chained equations.41 Ten imputations were performed in the development dataset and five imputations in the validation dataset–a pragmatic approach considering the large size of CPRD. The imputation model included all candidate predictors, Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function and outcome variables. The data analysis was undertaken using the Stata command “mi estimate” in a combined dataset that included all imputations.

Model development

Fractional polynomial regression analysis was used to model non-linear risks with continuous predictors. Nested models were employed to test whether a first-order polynomial provided a better fit than the continuous variable as a linear term. Assumptions of Cox proportional hazards model were checked using log-log plots and Schoenfeld residuals. Next, all candidate predictors were included in the Cox model and coefficients of each predictor estimated and combined using Rubin’s rule across the imputed datasets. The risk equation for predicting an individual’s risk of thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal blood-test results by 5-years was formulated using the development data. The baseline survival function at t = 5 years (S0), where all predictor values are set to zero was estimated along with the estimated regression coefficients (β1x1 + β2x2 + … + βpxp) and the individual’s predictor values (X). This led to the equation for the predicted risk of discontinuation at 5-years of 1−S0(t = 5)exp(Xβ).42

Model internal validation and shrinkage

We bootstrapped with replacement 500 samples of the data.43 The full model was fitted in each bootstrap sample, with its performance quantified in the bootstrap sample (apparent performance) and the original sample (test model performance), and the optimism calculated (difference in test and apparent performance). The shrinkage for each imputation was estimated as the average of calibration slopes (test model) over all bootstrap samples. The final uniform shrinkage calculated by averaging the estimated shrinkage estimates over all imputations. Optimism-adjusted estimates of performance for the original model were calculated as the original apparent performance minus the optimism.

To account for overfitting during model development, the original β coefficients were multiplied by the final uniform shrinkage factor and the baseline hazards re-estimated conditional on the shrunken β coefficients to ensure that overall calibration was maintained. The D statistic, a measure of discrimination, interpreted as a log hazard ratio (HR), the exponential of which gives the HR comparing two groups defined by above/below the median of the linear predictor was calculated.44,45 R2 was calculated from D statistic.

External validation

The final developed model equation was applied to the validation dataset, and calibration and discrimination were examined as above.44,45 Calibration of 5-year risks was examined by plotting agreement between estimated risk from the model and observed outcome risks. Predicted and observed risks were divided into 10 equally sized groups. Additionally, pseudo-observations were used to construct smooth calibration curves across all individuals via a running non-parametric smoother. Separate calibration plots were provided for each imputation. Age-group, inflammatory disease type, and whether the patient was commenced on thiopurine after the year 2010, formed the basis of sub-group analyses. Stata-MP version 16 was used for all statistical analyses and data visualisation.

This study was reported in line with the transparent reporting of a multivariate prediction model for individual prediction or diagnosis (TRIPOD) guidelines.46

Health economics analysis

Our model was used to estimate the probability of outcome over a five-year period in 10 patients, one from each risk decile. They were selected by ranking the patients in terms of risk and selecting a random patient at the 5th percentile, 15th percentile, and so on until the 95th percentile (Supplementary Table S1). Patients were monitored according to each strategy for a period of five years (four years in the biennial strategy although the impact of missed abnormal blood tests spanned the five-year period). An additional monitoring appointment after cessation of treatment due to an abnormal blood test was assumed. The probability that an abnormal blood test would result in an illness because of the extended monitoring period was estimated by the clinical team members based on their experience, erring towards over estimating the risk (Supplementary Table S2). The costs and quality-adjusted life year (QALYs) losses associated with each condition was estimated following targeted literature reviews (Supplementary Table S3). Both probabilistic and deterministic analyses were performed. A monitoring appointment and blood-tests was estimated to cost £24.09 (See: Supplementary Methods). No disutility was assumed for attending a monitoring appointment.

The costs associated with monitoring and illness were estimated, as were the loss in QALYs. All values were discounted at 3.5%/annum as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.47 Results were presented in terms of incremental net monetary benefit (iNMB), assuming a cost per QALY threshold of £20,000, compared with monitoring every three months. Sensitivity analysis considered three-fold higher risks of illnesses than estimated by clinicians. Health economic data analysis and visualisation were undertaken using Microsoft Excel.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. GN and AA had access to the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Data for 5982 and 3573 participants that contributed 16,117 and 9075 person-years follow-up were included in the development and validation cohorts, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2). The distribution of disease and demographic factors were similar between cohorts (Table 1). The median mercaptopurine equivalent dose was 48.1 mg/day (100 mg/day azathioprine). Fourteen candidate predictors (21 parameters) were included in the model (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Population selection criteria for model development.

Fig. 2.

Population selection criteria for model validation.

Table 2.

Final model hazard ratios and β-coefficients.

| Predictors | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | Coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 0.0120654 |

| Female sex | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28) | 0.0348383 |

| Mercaptopurine equivalent dose, (mg/day) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | −0.0031592 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.0021012 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Non-smoker/not recorded/ex-smoker | Reference | – |

| Current smoker | 0.98 (0.75, 1.29) | −0.0161052 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Non-drinker | Reference | – |

| Low (1–14 units/week) | 0.99 (0.79, 1.29) | −0.0119396 |

| Moderate (15–21 units/week) | 0.86 (0.50, 1.47) | −0.1516204 |

| Hazardous (>21 units/week) | 1.24 (0.83, 1.86) | 0.215067 |

| Ex-drinker | 0.86 (0.57, 1.30) | −0.1501354 |

| Inflammatory conditions | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Reference | – |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.56 (1.01, 2.42) | 0.4467324 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2.18 (1.47, 3.24) | 0.7810266 |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathyb | 1.33 (0.80, 2.22) | 0.2838247 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) | −0.0919595 |

| Chronic kidney disease stage-3c | 1.52 (1.05, 2.20) | 0.4197865 |

| Other immunosuppressive drugs | ||

| None | Reference | – |

| 5-aminosalicylatesd | 1.11 (0.89, 1.37) | 0.1014151 |

| Sulfasalazine | 0.70 (0.26, 1.89) | −0.3581131 |

| Methotrexate/leflunomide | 0.89 (0.12, 6.44) | −0.1177929 |

| Other drugs | ||

| Statins | 1.06 (0.77, 1.48) | 0.0629356 |

| Allopurinol | 0.95 (0.50, 1.81) | −0.0473062 |

| ACE inhibitors | 1.05 (0.75, 1.46) | 0.0440477 |

| At-least mild cytopenia or liver enzyme elevation in six-months preceding start of follow-up | 2.70 (2.17, 3.37) | 0.9939685 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. The reported values are before shrinkage.

Seronegative spondarthritis included psoriasis (±arthritis), ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis.

Patients with chronic kidney disease stages 4 and 5 were excluded from this study.

Included balsalazide, mesalazine, olsalazine.

Model development

Continuous predictors were not transformed as first-degree non-linear risk relationships were no better than linear terms (p > 0.05). Assumptions of Cox proportional hazards model were met (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Figure S1). 405 outcomes occurred during follow-up at an incidence (95% CI) of 25.13 (22.80–27.70)/1000 person-years. CKD, SLE, RA and either cytopenia or elevated liver enzymes during the first six months of primary-care prescription were strong predictors (Table 2). From the bootstrap, a uniform shrinkage factor of 0.80 was applied to all predictor coefficients. The final model’s cumulative baseline survival function (S0) was 0.938 at 5-years (Table 3). A generous number of decimal places are presented for the model coefficients. This will enable application of our model with less rounding error.

Table 3.

Equation to predict the risk of thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal monitoring blood test results after six months of primary care prescription and within the next 5-years.

| Risk score = 1−0.938exp(0.80βX) | |

|---|---|

| βX= | −0.0031592∗mercaptopurine equivalent daily dose |

| +0.0120654∗age in years at first primary-care prescription | |

| +0.0348383∗female-sex | |

| +0.0021012∗body mass index | |

| −0.0161052∗current smoker | |

| −0.0119396∗low alcohol intake | |

| −0.1516204∗moderate alcohol intake | |

| +0.215067∗hazardous alcohol intake | |

| −0.1501354∗ex-alcohol intake | |

| +0.4467324∗rheumatoid arthritis | |

| +0.7810266∗systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| +0.2838247∗seronegative spondarthritis | |

| −0.0919595∗diabetes | |

| +0.4197865∗chronic kidney disease stage-3 | |

| +0.1014151∗5-aminosalicylate | |

| −0.3581131∗sulfasalazine | |

| −0.1177929∗methotrexate or leflunomide | |

| +0.0629356∗statin | |

| −0.0473062∗allopurinol | |

| +0.0440477∗ACE-inhibitors | |

| +0.9939685∗at-least mild cytopenia or liver enzyme elevation within six-months of primary care thiopurine prescription. | |

Variables are coded 0 if absent, and 1 if present, respectively, except for mercaptopurine equivalent dose, age, and body mass index. 0.938 is the baseline survival function at 5-years and 0.80 is the shrinkage factor. Seronegative spondarthritis included psoriasis (±arthritis), ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis. Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease stages 4 and 5 were excluded from this study. 5-aminosalicylate Included balsalazide, mesalazine, olsalazine. Blood test abnormality defined as either cytopenia (neutrophil count <2 × 109/l, total leucocyte count <4 × 109/l, or platelet count <150 × 109/l) or raised transaminase levels (alanine transaminase and/or aspartate transaminase >35 IU/l) during the first six months of a prescription for methotrexate in primary care.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

The average model predictions matched the average observed outcome probabilities across all 10 groups of patients, with 95% CIs overlapping the 45-degree line (Fig. 3). Most patients had low risk of outcome and majority of deciles of predicted risk clustered at the lower end of the distribution (Supplementary Figure S2). The calibration curve at 5-years showed some mis-calibration at the individual level in the higher risk patients, however there were less data at the higher risk probabilities with wide 95% CIs (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figure S3). Royston D statistic (95% CI) was 0.91 (0.75–1.07), corresponding to HR (95% CI) 2.48 (2.12–2.92). The optimism adjusted Royston D statistic was 0.76 corresponding to HR 2.13 (Table 4).

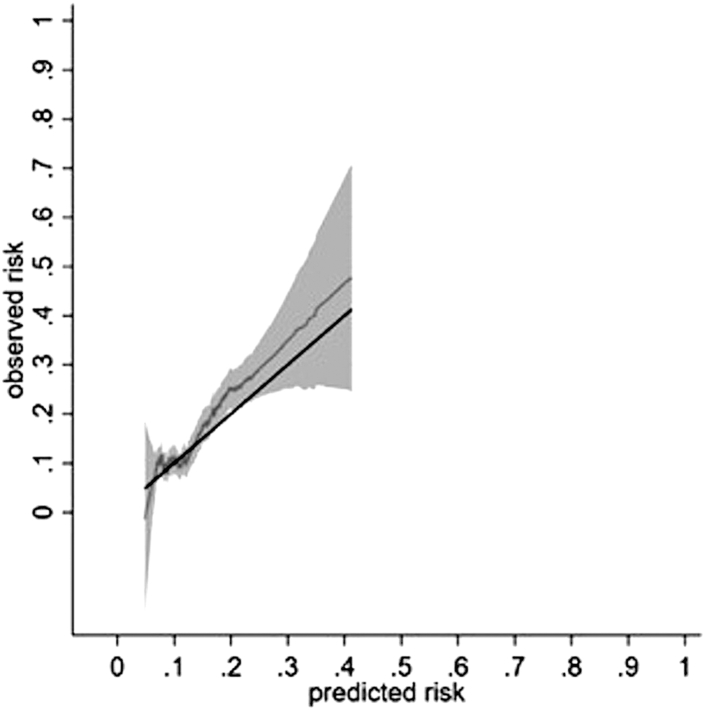

Fig. 3.

Calibration of a prognostic model for thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal monitoring blood-test results at 5 years in the development cohort. Data from a single imputed dataset was used for illustration; S0(t = 5) 0.938. Solid black line reflects perfect prediction.

Table 4.

Model diagnostics.

| Measure | Apparent performancea | Test performanceb | Average optimismc | Optimism corrected performanced | Performance in external validation (CPRD Gold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall calibration slope | 1.00 (0.84, 1.16) | 0.80 (0.64, 0.95) | 0.20 | 0.80 (0.64, 0.96) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.36) |

| R2 | 0.16 (0.12, 0.21) | 0.14 (0.10, 0.18) | 0.05 | 0.11 (0.07, 0.16) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.16) |

| Royston D statistic | 0.91 (0.75, 1.07) | 0.84 (0.68, 0.99) | 0.15 | 0.76 (0.60, 0.92) | 0.72 (0.52, 0.92) |

CPRD, Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Refers to performance (95% CI) estimated directly from the data that was used to develop the model.

Determined by executing full model in each bootstrap sample (500 samples with replacement), calculating bootstrap performance, and applying same model in original sample.

Average difference between model performance in bootstrap sample of the development dataset and performance in the development dataset.

Obtained by subtracting average optimism from apparent performance.

Model performance in the validation cohort

There were 269 outcomes incidence (95% CI) of 29.64 (26.30–33.40)/1000 person-years. The calibration slope (95% CI) across the 5-year follow-up period was 1.10 (0.84–1.36). The calibration plot showed reasonable correspondence between observed and predicted risk at 5-years across the tenths of risk (Supplementary Figure S4). Most predicted risk deciles clustered at lower end of the predicted risk distribution (Supplementary Figure S5). The smoothed calibration curve showed alignment of the predicted risk to the observed risk at low risk (Fig. 4). Model performance at years 1, 2, 3 and 4 showed a similar pattern (Supplementary Figures S6–S9). Model discrimination in the validation cohort was broadly similar to that in development cohort (Table 4). The Royston D statistic (95% CI) was 0.72 (0.52–0.92), corresponding to HR (95% CI) 2.05 (1.68–2.51). The model performed well across age-groups, in those with IBD, and in patients starting thiopurines in 2010 or later (Supplementary Figures S10 and S11).

Fig. 4.

Calibration of a prognostic model for thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal monitoring blood-test results at 5 years in the validation cohort. Data from a single imputed dataset was used for illustration; S0(t = 5) 0.938. Solid black line reflects perfect prediction.

Figs. 3 and 4 report the relationship between pseudo values of the observed risk and predicted risk via a running non-parametric smoother and therefore some values are less than zero. The pseudo values F1(t) are not constrained to fall within the range of 0–1, as they are jackknife quantitates that do not resemble individual event probabilities with the intention that E(F1(t)) = F1(t).48 None of the risks were less than zero when true values were used. Please see Supplementary Figures S3 and S5.

Cost-effectiveness

All extended monitoring periods were more cost-effective than three monthly monitoring (Fig. 5). Monitoring every two years was estimated to be most cost-effective, but at higher risks the difference between annual and biennial monitoring was moderate (estimated to be an iNMB <£60 per patient in the highest-risk decile). Probabilistic analyses provided results similar to deterministic analyses and results were robust to changes in key parameters. Supplementary Figure S12 shows the results when the risks of illnesses were assumed to be triple that estimated by the clinicians. In this sensitivity analysis, biennial monitoring was estimated to be most cost-effective up to decile 7, with annual monitoring most cost-effective for higher-risk deciles; all extended monitoring periods remained more cost-effective than 3-monthly monitoring. Disaggregated results for the base case are shown in Supplementary Table S5, with combined results in Supplementary Table S6.

Fig. 5.

The incremental net monetary benefit associated with extended monitoring periods compared to 3 monthly monitoring across deciles of predicted risk.

Discussion

We have developed and externally validated a prognostic model for clinically-significant thiopurine toxicity detected on monitoring blood-tests during long-term treatment. Our prognostic model performed well in predicting outcomes for up to five-years with excellent calibration and discrimination and in clinically relevant subgroups. It was cost-effective to increase the interval between monitoring blood-tests.

Target organ toxicity can occur several years after starting on thiopurines e.g., hepatotoxicity due to late metabolic shunting to 6-methylmercaptopurine ribonucleotide (6-MMPR) production occurred in 1.7% patients prescribed thiopurines after median 644 days of treatment.49 Another cohort study with long follow-up showed that adverse effects occur later in therapy, but are far less frequent in this period.11 It is in this later period that we propose our risk score has its utility. The risk-score output from the model may permit individualised monitoring strategies during long-term thiopurine treatment, with patients at low risk of toxicity undergoing less frequent blood-tests e.g., six monthly or annually. These findings should be considered by specialty guideline writing groups in order to modify their monitoring recommendations.

Nevertheless, regardless of the frequency of monitoring blood-tests undertaken, blood-test abnormalities should be should be acted upon as clinically appropriate. Due vigilance needs to be maintained for hepatic nodular regenerative hyperplasia which is indicated by thrombocytopenia and/or elevated liver enzymes and non-cirrhotic portal hypertension which may also manifest with anaemia, splenomegaly, variceal bleed, and/or ascites.50,51 The median time from starting azathioprine to hepatic nodular regenerative hyperplasia was 48 months in a large case-series.50

While our results indicate that the interval between monitoring blood-tests undertaken to screen for asymptomatic toxicity may be increased for the vast majority of patients prescribed thiopurines, blood-tests are an integral part of disease activity assessment in patients with many inflammatory conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Such blood tests should be undertaken when clinically indicated. For instance, it may be necessary to review a patient with active disease every three to six months with an updated full blood count, liver function tests, and urea, electrolytes and creatinine measurement in order to assess disease activity.

We did not have data on the date of first thiopurine prescription in the hospital clinic. As it typically takes four to six months to stabilise a patient on adequate dose of thiopurines in the UK, the model may be used to risk-stratify monitoring after six months of shared-care prescription or after one year from first thiopurine prescription in healthcare systems without shared care prescribing. As reported previously, increasing age, and prior blood-test abnormalities were strong predictors of thiopurine toxicity in the current study.52,53 The reduced thiopurine clearance in CKD and occurrence of renal involvement in SLE could also explain their being strong predictors of thiopurine toxicity in this study.12, 54

Genomic studies have established thiopurine methyl transferase (TPMT) activity prior to thiopurine prescription as a useful and cost-effective predictor of myelotoxicity, and though it has a clear place, TPMT testing cannot predict all myelosuppression.4,55, 56, 57 Unfortunately, the results of TPMT testing are not available in the CPRD and we were unable to include them in the prognostic model. For therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) there is uncertainty on how well it predicts future toxicity with 6-thioguanine nucleotides (6-TGN) and 6-MMPR. At treatment start TDM did not perform well in predicting hepatotoxicity and myelotoxicity in two studies but was a strong predictor of myelotoxicity in the TPOIC trial cohort.58, 59, 60 Another study reported more cases with leucopenia in the presence of high 6-TGN levels compared to low 6-TGN levels although the differences were not statistically significant.61 Reactive TDM during thiopurine treatment aids accurate ascertainment of toxicity, facilitates dose-reduction for dose-dependent side effects, and allows personalised dosing, thereby improving persistence on treatment and disease outcomes.62,63 TDM for thiopurines is not commonly performed in the UK and their results are not available in the CPRD. Further research is required to explore if the inclusion of TPMT, and TDM biomarkers at baseline would improve model performance. Future validation studies in Asian and Hispanic populations should also consider including polymorphisms in the nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety X-type motif (NUDT) 15 in the model as these polymorphisms are common in the Asian and Hispanic populations with a prevalence of 27%.64

There are several strengths of this study. We used a large real-world and nationally representative dataset for model development and a similar independent dataset for external validation allowing our results to have a high precision.14,15 We included a range of inflammatory diseases giving broad generalisability to the results. The outcome required the blood-test abnormality to be associated with thiopurine discontinuation, thereby predicting clinically relevant outcomes rather than minor or transient variations in blood parameters. Our health economic analysis provides evidence of cost efficacy for alternate monitoring strategies that were robust to changes in assumptions. Finally, as it is derived directly from available general practice data, the prognostic model could easily be built into GP electronic health records (e.g., as a calculator) to simplify its use.

However, several limitations of the study ought to be considered. First, we did not have data on concurrent use of biologics as these are hospital prescribed in the UK. However, there is no evidence that biologics increase the forms of thiopurine toxicity for which monitoring blood-tests are recommended.65,66 Second, the results of TPMT testing is not available in the CPRD. We do not believe that this is a major limitation as approximately 90% of Whites are not deficient in TPMT, and the vast majority of myelotoxicity due to TPMT deficiency occurs in the first few months of treatment.67,68 Participants included in our study were already prescribed thiopurines for at-least six months from primary-care after an initial period of prescription and monitoring from hospital outpatient clinic and most instances of myelotoxicity from thiopurine deficiency would have occurred before follow-up started and this prognostic model should not be used to replace the need for TPMT testing. Furthermore, the model performance was comparable in the years 2010 and after when TPMT testing became more widespread in the UK and in the entire cohort. Third, low numbers in the highest risk groups resulted in uncertainty regarding predictions for these groups. Fourth, the use of UK primary-care data for both model development and validation imply that further validation in other geographic regions may be required. Fifth, it might be argued that not performing competing risk regression is a weakness of our methodology, however, as there were very few (0.07%) deaths in the development cohort and no deaths in validation cohort during the 5-year follow-up period we do not believe this limits the validity of our findings. Sixth, patients that were prescribed thiopurines exclusively by a hospital specialist due to complex comorbidities and/or being at very high risk of toxicity were not included in this study. The prognostic model should not be used in this population. This is not a significant limitation as it is unusual to have such hospital prescribing and monitoring of thiopurines. Finally, as patients prescribed thioguanine were not included in this study, the results should not be extrapolated to this drug.

In conclusion, we developed an easy to use prognostic model for thiopurine discontinuation with abnormal monitoring blood-test results that may be used in clinical practice. It was cost-effective to monitor less frequently than is currently recommended. These findings should be of interest to guideline writing groups when considering recommendations upon the frequency of monitoring blood-tests during long-term thiopurine treatment.

Contributors

GN, MJG, HCW, TC, MWT, GPA, CPF, CDM, DAW, MDS, RDR, and AA designed the study. GN analysed the data supervised by MJG, RDR, and AA. GN and AA accessed and verified the underlying data. MDS performed health-economic analysis. GN, MJG, HCW, TC, MWT, GPA, CPF, CDM, DAW, MDS, RDR, and AA interpreted the data. AA and GN drafted the original submitted manuscript. AA led on the revision of the manuscript after peer review. All authors critically evaluated and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. AA is the guarantor.

Data sharing statement

Data used in the study are from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Due to CPRD licencing rules, we are unable to share data used in this study with third parties. The data used in this study may be obtained directly from the CPRD. Study protocol is available from www.cprd.com.

Declaration of interests

A.A. has received Institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotech; and personal fees from UpToDate (royalty), Springer (royalty), Cadilla Pharmaceuticals (lecture fees), NGM Bio (consulting), Limbic (consulting) and personal fees from Inflazome (consulting) unrelated to the work. GPA has received consulting fees from Abbott Products, Albireo Pharma, Amryth, AstraZeneca, BenevolentAI Bio, Clinipace, DNDI, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, NuCANA, Puretech, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, Servier Pharmaceuticals, W.L. Gore & Associates paid to the University of Nottingham unrelated to the work. CPF has received Consultancy/Advisory board fees from Abbvie, GenMab, Incyte, Morphosys, Roche, Takeda, Ono, Kite/Gilead, BMS/Celgene, BTG/Veriton and departmental research funding from BeiGene unrelated to the work. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Keele University has received research funding for CDM from NIHR, MRC, Versus Arthritis and BMS. CDM is Director of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research. HCW worked for the National Institute of Health Research 2015–2021. He had no part to play in the funding of this study.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) grant NIHR130580. The funders had no role in conducting and/or reporting this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102213.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Raine T., Bonovas S., Burisch J., et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(1):2–17. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feuerstein J.D., Ho E.Y., Shmidt E., et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(7):2496–2508. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feuerstein J.D., Isaacs K.L., Schneider Y., Siddique S.M., Falck-Ytter Y., Singh S. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450–1461. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb C.A., Kennedy N.A., Raine T., et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–s106. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanouriakis A., Tziolos N., Bertsias G., Boumpas D.T. Update οn the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(1):14–25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meggitt S.J., Anstey A.V., Mohd Mustapa M.F., et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of azathioprine 2011. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(4):711–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Rosa G.P., Marques S., Coelho F., et al. Azathioprine-induced interstitial nephritis in an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) myeloperoxidase (MPO) vasculitis patient. Eur J Rheumatol. 2018;5(2):135–138. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2017.17062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHenry P.M., Allan J.G., Rodger R.S., Lever R.S. Nephrotoxicity due to azathioprine. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(1):106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meys E., Devogelaer J.P., Geubel A., Rahier J., Nagant de Deuxchaisnes C. Fever, hepatitis and acute interstitial nephritis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Concurrent manifestations of azathioprine hypersensitivity. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(5):807–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parnham A.P., Dittmer I., Mathieson P.W., McIver A., Dudley C. Acute allergic reactions associated with azathioprine. Lancet. 1996;348(9026):542–543. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)64696-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis J.D., Abramson O., Pascua M., et al. Timing of myelosuppression during thiopurine therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: implications for monitoring recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.019. (quiz 1141–1192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Formulary Committee . BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2023. British national formulary. [85] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledingham J., Gullick N., Irving K., et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the prescription and monitoring of non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatology. 2017;56(6):865–868. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrett E., Gallagher A.M., Bhaskaran K., et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD) Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf A., Dedman D., Campbell J., et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD) Aurum. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(6) doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz034. 1740–1740g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis J.D., Bilker W.B., Weinstein R.B., Strom B.L. The relationship between time since registration and measured incidence rates in the general practice research database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(7):443–451. doi: 10.1002/pds.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abhishek A., Doherty M., Kuo C.F., Mallen C.D., Zhang W., Grainge M.J. Rheumatoid arthritis is getting less frequent-results of a nationwide population-based cohort study. Rheumatology. 2017;56(5):736–744. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledingham J., Gullick N., Irving K., et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the prescription and monitoring of non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatology. 2017;56(12):2257. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones S. 2018. METHOTREXATE (oral or subcutaneous) for psoriasis and other dermatological conditions.https://mm.wirral.nhs.uk/document_uploads/shared-care/Methotrexate_for_derm_diseases_shared_care_v2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHS England . 2022. National shared care protocol: methotrexate (oral and subcutaneous) for patients in adult services (excluding cancer care)https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/B1621_xvii_methotrexate-oral-and-subcutaneous-for-patients-in-adult-services-excluding-cancer-care.docx [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakafero G., Grainge M.J., Card T., et al. What is the incidence of methotrexate or leflunomide discontinuation related to cytopenia, liver enzyme elevation or kidney function decline? Rheumatology. 2021;60(12):5785–5794. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Section 2: AKI definition. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012;2(1):19–36. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalasani N., Björnsson E. Risk factors for idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2246–2259. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safy-Khan M., de Hair M.J.H., Welsing P.M.J., van Laar J.M., Jacobs J.W.G. Current smoking negatively affects the response to methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis in a dose-responsive way, independently of concomitant prednisone use. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(10):1504–1507. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkes G.C., Whelan K., Lindsay J.O. Smoking in inflammatory bowel disease: impact on disease course and insights into the aetiology of its effect. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(8):717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parisis D., Bernier C., Chasset F., Arnaud L. Impact of tobacco smoking upon disease risk, activity and therapeutic response in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(11) doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klotz U. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sulphasalazine, its metabolites and other prodrugs of 5-aminosalicylic acid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):285–302. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broekman M., Coenen M.J.H., van Marrewijk C.J., et al. More dose-dependent side effects with mercaptopurine over azathioprine in IBD treatment due to relatively higher dosing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(10):1873–1881. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandborn W.J. Rational dosing of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2001;48(5):591–592. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.5.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ansari A., Elliott T., Baburajan B., et al. Long-term outcome of using allopurinol co-therapy as a strategy for overcoming thiopurine hepatotoxicity in treating inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(6):734–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansari A., Patel N., Sanderson J., O'Donohue J., Duley J.A., Florin T.H. Low-dose azathioprine or mercaptopurine in combination with allopurinol can bypass many adverse drug reactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(6):640–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith M.A., Blaker P., Marinaki A.M., Anderson S.H., Irving P.M., Sanderson J.D. Optimising outcome on thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease by co-prescription of allopurinol. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiszka-Kanowitz M., Theede K., Thomsen S.B., et al. Low-dose azathioprine and allopurinol versus azathioprine monotherapy in patients with ulcerative colitis (AAUC): an investigator-initiated, open, multicenter, parallel-arm, randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;45 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warner B., Johnston E., Arenas-Hernandez M., Marinaki A., Irving P., Sanderson J. A practical guide to thiopurine prescribing and monitoring in IBD. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2016-100738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hande S., Wilson-Rich N., Bousvaros A., et al. 5-aminosalicylate therapy is associated with higher 6-thioguanine levels in adults and children with inflammatory bowel disease in remission on 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(4):251–257. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000206544.05661.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao X., Zhang F.B., Ding L., et al. The potential influence of 5-aminosalicylic acid on the induction of myelotoxicity during thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(8):958–964. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283545ae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meijer B., Wilhelm A.J., Mulder C.J.J., Bouma G., van Bodegraven A.A., de Boer N.K.H. Pharmacology of thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease and complete blood cell count outcomes: a 5-year database study. Ther Drug Monit. 2017;39(4):399–405. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dirven L., Klarenbeek N.B., van den Broek M., et al. Risk of alanine transferase (ALT) elevation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate in a DAS-steered strategy. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(5):585–590. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gisbert J.P., Niño P., Rodrigo L., Cara C., Guijarro L.G. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity and adverse effects of azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: long-term follow-up study of 394 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2769–2776. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley R.D., Ensor J., Snell K.I.E., et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schafer J.L. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steyerberg E.W. Springer International Publishing AG; Cham, Switzerland: 2019. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakafero G., Grainge M.J., Williams H.C., et al. Risk stratified monitoring for methotrexate toxicity in immune mediated inflammatory diseases: prognostic model development and validation using primary care data from the UK. BMJ. 2023;381 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-074678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royston P., Altman D.G. External validation of a Cox prognostic model: principles and methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox D.R. Note on grouping. J Am Stat Assoc. 1957;52(280):543–547. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moons K.G., Altman D.G., Reitsma J.B., et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):W1–W73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NICE . 2022. NICE health technology evaluations: the manual.https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/resources/nice-health-technology-evaluations-the-manual-pdf-72286779244741 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Royston P. Tools for checking calibration of a Cox model in external validation: approach based on individual event probabilities. Stata J. 2014;14(4):738–755. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munnig-Schmidt E., Zhang M., Mulder C.J., Barclay M.L. Late-onset rise of 6-MMP metabolites in IBD patients on azathioprine or mercaptopurine. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(4):892–896. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vernier-Massouille G., Cosnes J., Lemann M., et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine. Gut. 2007;56(10):1404–1409. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.114363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simsek M., Meijer B., Ramsoekh D., et al. Clinical course of nodular regenerative hyperplasia in thiopurine treated inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):568–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broekman M., Coenen M.J.H., Wanten G.J., et al. Risk factors for thiopurine-induced myelosuppression and infections in inflammatory bowel disease patients with a normal TPMT genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(10):953–963. doi: 10.1111/apt.14323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calafat M., Mañosa M., Cañete F., et al. Increased risk of thiopurine-related adverse events in elderly patients with IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(7):780–788. doi: 10.1111/apt.15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz-Irastorza G., Khamashta M.A., Castellino G., Hughes G.R. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2001;357(9261):1027–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fangbin Z., Xiang G., Minhu C., et al. Should thiopurine methyltransferase genotypes and phenotypes be measured before thiopurine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther Drug Monit. 2012;34(6):695–701. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3182731925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickson A.L., Daniel L.L., Zanussi J., et al. TPMT and NUDT15 variants predict discontinuation of azathioprine for myelotoxicity in patients with inflammatory disease: real-world clinical results. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(1):263–271. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winter J., Walker A., Shapiro D., Gaffney D., Spooner R.J., Mills P.R. Cost-effectiveness of thiopurine methyltransferase genotype screening in patients about to commence azathioprine therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(6):593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Moorsel S.A.W., Deben D.S., Creemers R.H., et al. Predictive algorithm for thiopurine-induced hepatotoxicity in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2022;44(6):747–754. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.González-Lama Y., Bermejo F., López-Sanromán A., et al. Thiopurine methyl-transferase activity and azathioprine metabolite concentrations do not predict clinical outcome in thiopurine-treated inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(5):544–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong D.R., Coenen M.J., Vermeulen S.H., et al. Early assessment of thiopurine metabolites identifies patients at risk of thiopurine-induced leukopenia in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(2):175–184. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boekema M., Horjus-Talabur Horje C.S., Roosenboom B., Roovers L., van Luin M. Therapeutic drug monitoring of thiopurines: effect of reduced 6-thioguanine nucleotide target levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(8):3741–3748. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnes A., Ooi S.J., Lynch K.D., et al. Proactive metabolite testing in patients on thiopurine may yield long-term clinical benefits in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(3):889–896. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07556-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meijer B., Kreijne J.E., van Moorsel S.A.W., et al. 6-methylmercaptopurine-induced leukocytopenia during thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(6):1183–1190. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desai D., Jena A., Sharma V., Hibi T. Time to incorporate preemptive NUDT15 testing before starting thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease in Asia and beyond: a review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2023;16(7):643–653. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2023.2232300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Labidi A., Hafi M., Ben Mustapha N., Serghini M., Fekih M., Boubaker J. Toxicity profile of thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. Tunis Med. 2020;98(5):404–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong D.R., Coenen M.J.H., Derijks L.J.J., et al. Early prediction of thiopurine-induced hepatotoxicity in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(3):391–402. doi: 10.1111/apt.13879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lennard L. TPMT in the treatment of Crohn's disease with azathioprine. Gut. 2002;51(2):143–146. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qasim A., Seery J., Buckley M., Morain C.O. TPMT in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease with azathioprine. Gut. 2003;52(5):767. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.767. (author reply 767–767) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.