Summary

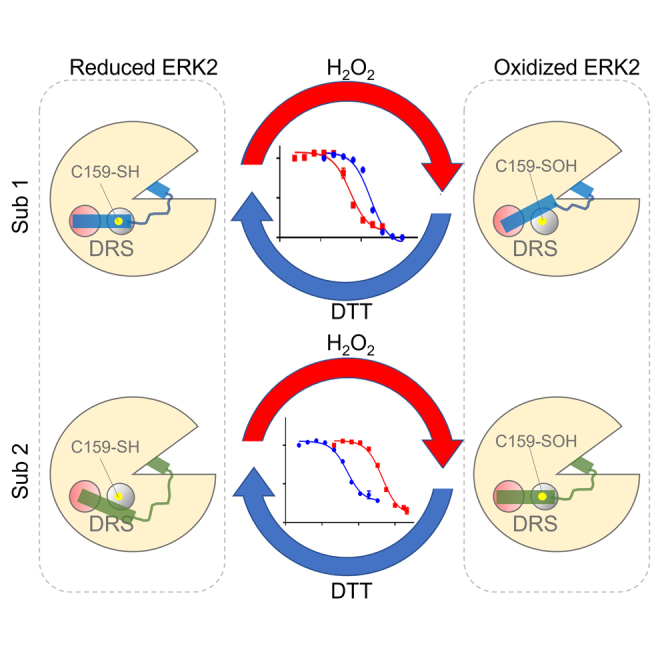

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) are dysregulated in many pervasive diseases. Recently, we discovered that ERK1/2 is oxidized by signal-generated hydrogen peroxide in various cell types. Since the putative sites of oxidation lie within or near ERK1/2’s ligand-binding surfaces, we investigated how oxidation of ERK2 regulates interactions with the model substrates Sub-D and Sub-F. These studies revealed that ERK2 undergoes sulfenylation at C159 on its D-recruitment site surface and that this modification modulates ERK2 activity differentially between substrates. Integrated biochemical, computational, and mutational analyses suggest a plausible mechanism for peroxide-dependent changes in ERK2-substrate interactions. Interestingly, oxidation decreased ERK2’s affinity for some D-site ligands while increasing its affinity for others. Finally, oxidation by signal-generated peroxide enhanced ERK1/2’s ability to phosphorylate ribosomal S6 kinase A1 (RSK1) in HeLa cells. Together, these studies lay the foundation for examining crosstalk between redox- and phosphorylation-dependent signaling at the level of kinase-substrate selection.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Biochemistry, Molecular biology, Cell biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

ERK2 is sulfenylated by H2O2 on Cys159 within its DRS ligand binding domain

-

•

Oxidation of ERK2 differentially alters its activity toward model ERK2 substrates

-

•

DRS ligands have alternate preferences for oxidized versus reduced ERK2

-

•

Signal-generated H2O2 promotes ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of RSK1

Biological sciences; Biochemistry; Molecular biology; Cell biology

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the collective term used to describe all highly reactive oxygen derivatives, including superoxide (O2.-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In addition to the incidental generation of ROS that occurs during cellular respiration, the regulated production of ROS by dedicated ROS-generating enzymes such as NADPH oxidase (NOX) is now recognized as an essential source of intracellular oxidants in normal and disease states.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Together with antioxidant enzymes involved in ROS degradation, such as catalase and members of the redoxin superfamily, the selective activation of NOX family members leads to the production of discrete pools of ROS that function as key second messengers in redox-dependent signaling pathways.1,3,7,8,9 Recently, redox-dependent signaling has been shown to play a critical role in physiological processes, such as aging, cell proliferation, immune response, and several pervasive diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.2,4,5,7,10,11 While our understanding of the mechanisms controlling ROS levels inside cells has grown considerably over the past two decades, less is known about the molecular signaling events that occur downstream of ROS generation.

Oxidation-induced changes in the size, charge, and chemical properties of redox-sensitive Cys residues can impact protein function in several ways. For instance, sulfenylation has been shown to alter the stability, localization, protein-protein interactions, and/or enzymatic activity of cellular proteins.4,5,7,12,13,14,15,16,17 In many cases, redox-dependent mechanisms directly influence other signaling pathways. For example, protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), perhaps the most well-studied downstream effectors of H2O2-mediated signaling, are inhibited by reversible modification of an active site Cys residue required for hydrolysis of the phosphate monoester bond.3,18 Likewise, a growing body of evidence suggests that protein kinases are also directly regulated by ROS.13,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 However, unlike PTPs, whose activity is universally inhibited by oxidation, the effect of oxidation on kinase function is more idiosyncratic, with both oxidation-induced activation and inactivation being reported (sometimes for the same kinase).12,20,21,23,26,27,30,31,32 Likewise, the positions of the redox-sensitive Cys residue(s) in the kinase sequence and the molecular consequences of oxidation are more varied in kinases than in PTPs.12,20,23,25,27,28,33,34 Interestingly, in several redox-sensitive kinases, the modified Cys is located in a region involved in substrate binding (e.g., the activation loop or docking regions).25,30,31,32,35 This raises the intriguing possibility that oxidation may shift the substrate preference of a given kinase such that distinct subsets of substrates are phosphorylated in the oxidized and reduced states.

Recently, using the sulfenylation-specific probe, DCP-Bio1, we discovered that the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family members, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), are oxidized by signal-generated H2O2 in several cell lines following treatment with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), or lysophosphatidic acid (LPA).36 ERK1/2, critical components of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling axis, are essential in regulating various cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis.37,38,39,40 As a consequence, dysregulation of ERK1/2 signaling has been implicated in many disorders, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegeneration.41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 While several reports suggest that the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling axis is modulated by both exogenous and endogenous H2O2, to date, most studies have focused on oxidation-dependent changes in enzymes that lie either upstream (e.g., activation of MAPK kinase kinases (MAP3Ks)) or downstream (e.g., inactivation of certain PTPs) of ERK1/2.50,51,52,53 The cumulative effect of redox regulation of these enzymes is an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation on T183 and Y185 (according to Rattus norvegicus ERK2 numbering), which leads to a dramatic increase in ERK1/2 activity. Thus, it is often assumed that oxidation leads to increased phosphorylation of substrates traditionally associated with ERK1/2-regulated processes, such as proliferation, migration, and the insulin response. However, in many cases, the phosphorylation status of downstream ERK1/2 substrates was not examined following oxidation-induced increases in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Here, we first investigated the effect of H2O2-dependent oxidation on the substrate selection of ERK2 using the model ERK2 substrates, Sub-D and Sub-F. We found that oxidation of ERK2 by H2O2 alters its activity toward Sub-D while having little effect on Sub-F. Computational modeling and mutational analysis suggest a plausible mechanism involving displacement of Sub-D from ERK2’s D-recruitment site (DRS). We then examined the effect of H2O2-dependent oxidation on ERK2’s interactions with other ligands using a fluorescence polarization-based binding assay. These studies suggest that oxidation of ERK2 by H2O2 alters its preference for some DRS ligands (both positively and negatively) while having little effect on others. Consistently, cell-based validation experiments in HeLa cells suggest that oxidation by signal-generated H2O2 promotes interactions between ERK1/2 and ribosomal S6 kinase A1 (RSK1), leading to increased phosphorylation of RSK1 under oxidizing conditions. Together, these studies offer new insights into crosstalk mechanisms between redox- and ERK-mediated signaling and lay a foundation to examine the impact of redox modification on the substrate selection of protein kinases in general, and MAPKs, in particular.

Results

Identification of putative sites of ERK1/2 oxidation

We previously demonstrated that signal-generated H2O2 oxidizes endogenous ERK1/2 during proliferative signaling in various cell types, including in growth factor-stimulated NIH3T3 fibroblasts, HeLa cervical epithelial cancer cells, and SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells.36 To identify putative sites of ERK1/2 oxidation, we first used the prediction tool, Cy-Preds, to determine which cysteine (Cys, C) residues on doubly-phosphorylated ERK1 (PDB: 6GES) and ERK2 (PDB: 2ERK) might be most susceptible to oxidation.54,55,56 Based on Cy-Preds predictions, which combine energy- and structure-based methods with similarity-based scoring algorithms, doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 was predicted to undergo oxidation on C159 (Figure 1A; according to Rattus norvegicus ERK2 numbering). Interestingly, in addition to C159, unphosphorylated ERK2 (PDB: 1ERK) was also predicted to be oxidized on C252 (Figure S1). In the case of ERK1, both C178 (which corresponds to ERK2C159) and C271 (corresponding to ERK2C252) are predicted to be oxidized regardless of the enzyme’s phosphorylation status (Figure S1). To test these predictions experimentally, we used the sulfenylation-selective probe, dimedone, and mass spectrometry-based analysis to identify sulfenylation (-SOH) sites at various H2O2 concentrations (Figures 1B and 1C). During these studies, we focused on doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 due to the wealth of biochemical and structural data available for this enzyme and the relative simplicity of its predicted oxidation profile. Consistent with the computational predictions, mass spectrometric analysis suggests that ERK2C159 is extremely susceptible to oxidation (even undergoing some degree of adventitious oxidation during mock treatment) while ERK2C252 is much less reactive, only forming dimedone conjugates at H2O2 concentrations over 500 μM (Figure 1C). Tracking reactivity of ERK2 with the fluorescent thiol alkylating agent, monobromobimane, across a pH range, the fit of the data to a single ionization site (cysteine thiol or thiolate) yields a pKa of 6.35 ± 0.09 (Figure S2). Pre-incubation of ERK2 with the C159-specific inhibitor, BI-78D3, completely abolished reactivity toward monobromobimane across our pH range.57 This, together with data in Figure 1C, suggests that the observed pKa corresponds to that of the reactive ERK2C159 residue. This value is more than two pH units lower than the pKa of free sulfhydryls, suggesting that most ERKC159 is the thiolate species under physiological conditions. This would make this residue more susceptible to oxidation since thiolates are significantly stronger nucleophiles than thiols and generally react more readily with H2O2. Oxidation does not appear to promote disulfide bond formation in vitro or in cells (Figure S3). This, coupled with its reactivity toward dimedone, suggests that ERK2C159 is likely to be sulfenylated at low concentrations of H2O2 and may form higher-order oxoforms at elevated H2O2 levels. Meanwhile, ERK2C252 can be sulfenylated but only at relatively high H2O2 concentrations.

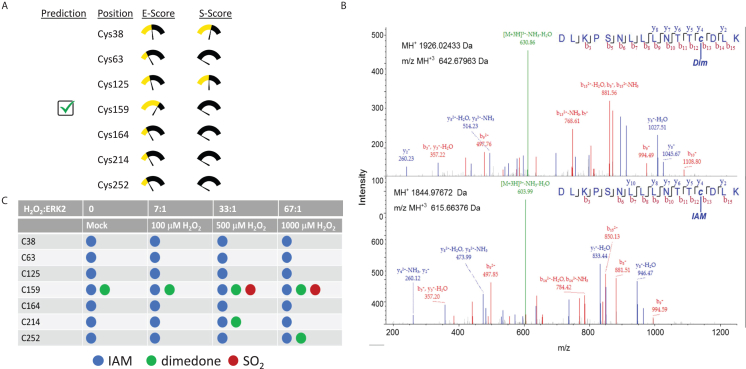

Figure 1.

Identification of ERK2 Cysteine Sensitivity to Sulfenylation by H2O2

(A) Putative sites of oxidation on ERK2 (PDB: 2ERK) predicted by Cy-Preds using the cysteine oxidation prediction algorithm (COPA). E-score: energy score; S-score: similarity score.

(B) Purified ERK2 (15 μM) was treated with either dH2O (mock) or 100 μM, 500 μM, or 1000 μM H2O2 (corresponding to H2O2-to-ERK2 molar ratios of ∼7:1, ∼33:1, and ∼67:1, respectively) for 1 h in the presence of 7 mM dimedone at room temperature. Free thiols were then alkylated by iodoacetamide (IAM), and the protein was precipitated and resuspended in 10% acetonitrile and 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate before being digested overnight with trypsin at 37°C. Peptides were then analyzed using a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL. The mass spectra for ERK2C159 following oxidation by 100 μM H2O2 are shown.

(C) Summary of mass spectrometry experiments showing conjugation of each Cys residue in ERK2 following treatment with the indicated concentration of H2O2. SO2: sulfinic acid. Note that dimedone can only be conjugated to sulfenylated Cys residues. See also Figures S1–S3.

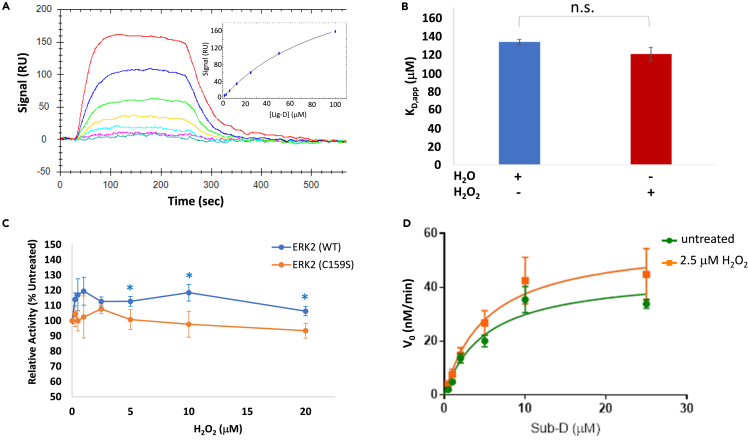

Oxidation of ERK2 affects its activity toward D- and F-site peptide substrates differently

Interestingly, C159 and C252 lie either within or close to ligand docking surfaces on ERK2 (Figure 2A). For instance, C159 is positioned on the ridge formed between the two hydrophobic binding pockets (ΦA and ΦB) in the DRS.58,59,60 Meanwhile, C252 is located just outside the FRS binding groove. Because sulfenylation alters the modified Cys residue’s size and chemical properties, we asked whether oxidation could disrupt, or otherwise perturb, ERK2-substrate interactions. To this end, we treated purified ERK2 with various concentrations of H2O2 and then, after scavenging excess H2O2 with catalase, measured its activity toward the DRS- and FRS-specific peptide substrates, Sub-D and Sub-F, respectively (Figures 2B and 2C).61 Consistent with the Cy-Preds predictions and our dimedone labeling experiments, H2O2-dependent oxidation had little effect on ERK2’s ability to phosphorylate the FRS substrate, Sub-F (Figure 2D). In contrast, oxidation of ERK2 led to a small (∼16%) but statistically significant increase in Sub-D activity at low H2O2 concentrations followed by a gradual decrease in Sub-D phosphorylation at higher peroxide concentrations (Figure 2D). While the decrease in activity toward Sub-D at elevated H2O2 concentrations is likely due to the formation of higher-order oxoforms such as sulfinic acid (e.g., see Figure 1C) that may only occur under extreme conditions inside the cell, we were intrigued by the apparent increase in activity toward Sub-D at low H2O2 concentrations. Therefore, we titrated over a narrower H2O2 concentration range that is more likely to be found under cellular conditions (Figure 2E).62,63,64 As before, ERK2 oxidation did not affect its ability to phosphorylate Sub-F. Notably, over this narrower concentration range, we observed a dose-dependent increase in ERK2 activity toward Sub-D that plateaued at 20% above the untreated control before decreasing slightly at 20 μM H2O2.

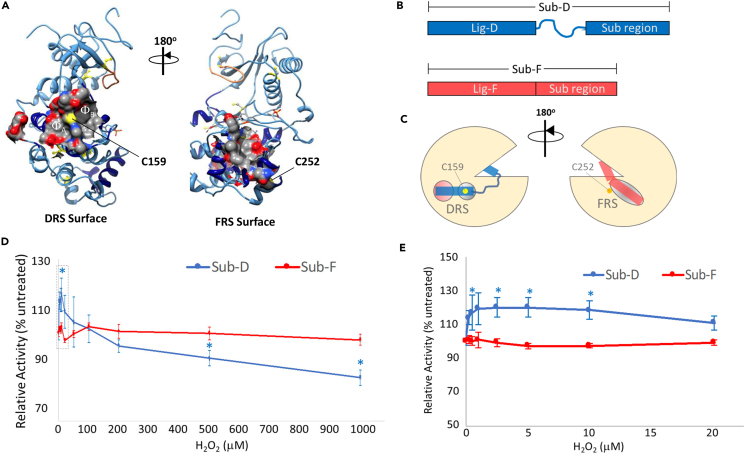

Figure 2.

Oxidation of ERK2 Selectively Affects Activity Toward a Model D-site Recruitment Surface (DRS) Substrate

(A) Ribbon diagram of ERK2 (PDB: 2ERK) highlighting the D-recruitment site (DRS) surface (left) and the F-recruitment site (FRS) surface (right) as electrostatic density maps. The hydrophobic A and B pockets (φA and φB, respectively) in the DRS are shown. C159 (yellow) lies between φA and φB within the DRS while C252 is positioned close to the FRS.

(B) The DRS-specific peptide substrate, Sub-D, is composed of the Lig-D ligand binding domain linked, via a 6-aminohexanoic acid linker, to the substrate region. Meanwhile, the FRS-specific peptide substrate, Sub-F, is composed of Lig-F linked to the same substrate region used by Sub-D.

(C) Schematic diagram illustrating how Sub-D and Sub-F are believed to bind ERK1/2 via the DRS and FRS, respectively.

(D and E) Relative activity of ERK2 toward Sub-D (blue) and Sub-F (red) following oxidation of ERK2 using the indicated concentrations of H2O2 over a broad (D) and a narrower (E) H2O2 range. Each data point represents the average of at least 4 independent experiments repeated in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard error about the mean. Average activities toward Sub-D that were significantly different from those toward Sub-F at the corresponding H2O2 concentration are indicated by an asterisk (∗; p < 0.05).

Oxidation of ERK2 alters its interactions with model DRS ligands

To better understand the impact that H2O2-dependent oxidation has on the activity of ERK2 toward Sub-D, we next used steady-state kinetic analysis to measure reaction parameters such as the initial velocity (v0), maximal velocity (Vmax), and the Michaelis constant, Km, under conditions similar to those used during the titration experiments. Kinetic analysis can reveal useful information about interactions between the kinase and a given substrate. For instance, for most kinases, the dissociation rate of the enzyme-substrate complex, k-1, is believed to be greater than the rate of product formation, k2. In the case of ERK2, this assumption has been verified experimentally for the model substrate, EtsΔ138.65 Under these circumstances, Km is a measure of the dissociation constant, KD, of the enzyme-substrate complex.66 Likewise, since each kinase molecule contains one active site, the kinetic constant, kcat (equivalent to k2 described above), can be calculated by dividing Vmax by the kinase concentration used during the reaction.

Using this strategy, we examined how H2O2-dependent oxidation affects ERK2 interactions with Sub-D (Figure 3). During these experiments, we chose to treat ERK2 with 2.5 μM H2O2 (corresponding to an ∼7:1 M ratio of H2O2-to-ERK2) because this concentration led to a maximal increase in ERK2’s activity toward Sub-D. It is also important to note that, at this molar ratio, we only observed sulfenylated and reduced forms of ERK2C159 by MS. These experiments suggest that oxidation of ERK2 affects its interaction with Sub-D in several related ways (Figure 3A; Table 1). For example, in the absence of H2O2 (i.e., the untreated control), ERK2 exhibited a Km,app toward Sub-D of 2.4 ± 0.3 μM, which is very similar to the value of 2.5 ± 1.5 μM reported previously for ERK2-Sub-D interactions.61 However, when the enzyme was pre-treated with 2.5 μM H2O2, the Km,app increased 2.4-fold to 5.8 ± 0.9 μM, suggesting that oxidation of ERK2 decreases its affinity for Sub-D. Interestingly, the decrease in affinity was accompanied by an ∼68% increase in kcat,app, indicating that oxidation also increases turnover. Such behavior will be expected if ERK2 oxidation increases Km without affecting its affinity for the transition state (TS).67 This is consistent with the notion that ERK2 recognizes Sub-D primarily via a docking site (i.e., the DRS) far removed from the active site where the TS is bound.61,65 Together, these effects led to an approximately 40% decrease in catalytic efficiency, defined as kcat/Km, following oxidation. Conversely, little to no difference was observed in either Km,app, or kcat,app when ATP levels were varied while holding Sub-D constant, suggesting that the kinase active site is mostly unaffected by oxidation (Figure 3B; Table 1).

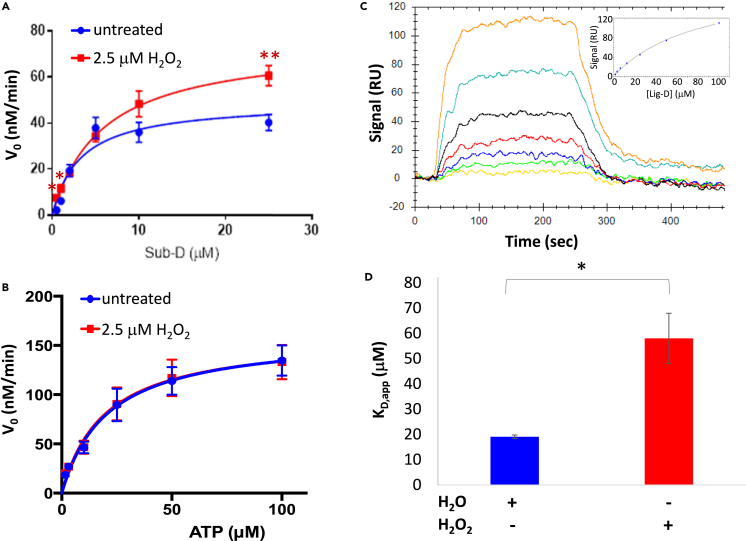

Figure 3.

Biochemical and Biophysical Analysis of ERK2-Sub-D Interactions

(A and B) Steady-state kinetics analysis of ERK2 toward Sub-D following pre-treatment of ERK2 with 2.5 μM H2O2 (red) or dH2O (untreated; blue). In (A), the concentration of Sub-D was varied while holding ATP constant at 20 μM while in (B), Sub-D was held constant at 1 μM while varying ATP levels. Error bars represent standard error about the mean (n > 3 independent experiments repeated in duplicate). Those points that exhibited a statistically significant difference in initial velocity (v0) between treated and untreated samples are indicated by an asterisk (∗; p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(C) Representative equilibrium binding experiment (from among 3 independent experiments done in duplicate) measuring the affinity of oxidized ERK2 for Lig-D using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) at Lig-D concentrations ranging from 1.6 to 100 μM. The binding curve is shown in the inset.

(D) Average KD,app for untreated ERK2 (blue) and ERK2 treated with 2.5 μM H2O2 before immobilization (n = 3 independent experiments repeated in duplicate). Error bars represent standard error about the mean. Statistically significant differences are indicated by an asterisk (∗, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

ERK2 steady-state kinetics vs. Sub-D or ATP

| WT ERK2 vs. Sub-D |

WT ERK2 vs. ATP |

ERK2(C159S) vs. Sub-D |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 2.5 μM H2O2 | Change (p value | Untreated | 2.5 μM H2O2 | Change (p value | Untreated | 2.5 μM H2O2 | Change (p value | |

| kcat,app(s−1) | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 1.68-f (0.02) | 53.3 ± 6.6 | 55.7 ± 6.7 | 1.05-f (0.2) | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 11.3 ± 2.6 | 1.35-f (0.4) |

| Km,app (μM) | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 2.43-f (0.02) | 19.9 ± 0.9 | 23.0 ± 2.6 | 1.15-f (0.2) | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | −1.07-f (0.5) |

| kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | 3.8 x 106 | 2.7 x 106 | −1.41-f (0.06) | 2.7 x 106 | 2.7 x 106 | −1.02-f(0.8) | 1.9 x 106 | 2.1 x 106 | 1.13-f (0.7) |

Sub-D is a modular peptide composed of a DRS-binding region, termed Lig-D, linked to a substrate region via a short 6-aminohexanoic acid linker (Figure 2B). Based on trans-phosphorylation assays and steady-state kinetics analysis, we suspected that oxidation primarily affects ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of Sub-D by altering binding interactions between ERK2 and Sub-D within the DRS. Therefore, to focus more directly on H2O2-dependent changes within the DRS itself, we treated ERK2 with or without H2O2 and measured its affinity for Lig-D using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Figure 3C). During these experiments, we were careful to maintain an H2O2:ERK2 ratio of ∼7:1, which corresponds to a molar ratio similar to that used during steady-state kinetics analysis. In the absence of H2O2 pre-treatment, ERK2 exhibited a KD,app for Lig-D of 19.1 ± 0.7μM under equilibrium conditions (Figure 3D). This is very similar to the Ki,app of 20 ± 4 μM reported for Lig-D acting as a competitive inhibitor toward Sub-D.68 In contrast, pre-incubation of ERK2 with H2O2 led to an ∼3-fold increase in KD,app to 58.0 ± 9.9 μM. These data, which are reminiscent of the increase in Km,app between ERK2 and Sub-D observed during steady-state kinetics analysis, suggest that oxidation of ERK2 disrupts its interactions with Lig-D within the DRS.

Computational analysis of H2O2-induced changes in ERK2-Lig-D interactions

To gain additional insights into the molecular factors that may be driving H2O2-induced changes in ERK2-Lig-D binding, we used computational modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to examine interactions between ERK2 and Lig-D (Figure 4). To this end, the ligand docking program, AutoDock, was used to model Lig-D interactions with ERK2 in the oxidized and reduced states.69 To assess changes in docking that may occur within the sulfenylated form of ERK2, the sulfhydryl group on C159 (PDB: 2ERK) was first converted to sulfenic acid (C159-SOH) using Chimera 1.12. Then the Lig-D peptide was introduced into the structure for docking.70 During docking, Lig-D was treated as a semi-rigid structure with most side chains flexible, while ERK2 structures were treated as rigid. A sufficiently large gridbox (74 × 74 × 74 Å) was created to allow space to search favorable interactions between Lig-D and ERK2. Finally, after docking, the top-ranked models were refined by MD simulations using GROMACS.71 The fidelity of the models generated during molecular dynamics simulations were evaluated based on several criteria, including reproducibility across multiple models, energetics, and consistency with existing biochemical data.

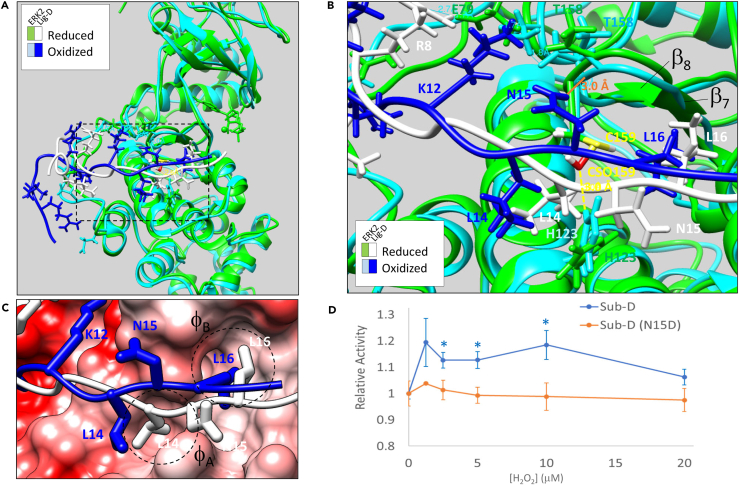

Figure 4.

Computational Modeling and Biochemical Investigation of ERK2-Lig-D Interactions

(A) Overlay of the final trajectories of 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations of the ERK2-Lig-D binding interaction with ERK2 in the oxidized (ERK2 in cyan; Lig-D in royal blue) and reduced (ERK2 in green; Lig-D in white) states.

(B) Close-up of the region boxed in A. Key residues in ERK2 and Lig-D are labeled in the color corresponding to the respective model. An H-bond that forms between Lig-DN15 and the backbone carbonyl of ERK2T158 in the oxidized state is shown (solid orange line). Likewise, the distance between the sulfenylated form of C159 (CSO159) and ERK2H123 in the oxidized state is shown (dashed yellow line).

(C) Coulombic surface representation of ERK2-Lig-D showing the positions of Lig-DL14 and Lig-DL16 relative to hydrophobic pockets A and B (φA and φB, respectively) in the DRS.

(D) Relative activity of ERK2 toward Sub-D (blue) or Sub-D(N15D) following oxidation of ERK2 with the indicated concentrations of H2O2. Data points and error bars are as in Figure 2E. Statistically significant differences between ERK2 activity toward Sub-D and Sub-D(N15D) are indicated by an asterisk (∗, p < 0.05). All structure images were generated using UCSF Chimera software (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/).

With respect to the reduced ERK2-Lig-D complex, MD simulations yielded 14,004 solutions that exhibited a root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of <2.5 Å. These solutions clustered into 9 distinct groups, with 10,615 solutions (76.8%) being found in the top-ranked cluster. The binding modes within the top-ranked cluster shared several key characteristics with both the crystal structure of the yeast ERK2 homolog, FUS3, bound to the MAPK docking segment from STE7 (PDB: 2B9H) and a previously reported model of the ERK2-Lig-D ternary complex generated using the software package, Modeler.68,72 For instance, similar to the other ERK2-Lig-D complexes, when ERK2 is in the reduced state, the side-chains of Lig-D residues R7 and R8 interact with negatively charged residues in the common docking motif while residues L14 and L16 insert into hydrophobic pockets, φA and φB, respectively, on the DRS (Figures 4A–4C). Likewise, Lig-DN15 lies just above ERK2H123 and points away from the DRS, preventing interactions between N15 and the kinase. Overall, the binding mode conforms to the STE7 sub-type of the greater HePTP class of MAPK docking motifs.73 This is not surprising given that Lig-D is derived from the DRS binding region of STE7.68 The high degree of similarity between our predicted structure of Lig-D and ERK2 in the reduced state and those obtained both experimentally (i.e., FUS3-pepSTE7) and using a different modeling platform (i.e., Modeler) suggest that the AutoDock predictions can capture salient features of the ERK2-Lig-D binding interaction.

In contrast to the model generated in the reduced state, sulfenylation of ERK2C159 causes subtle changes in the architecture within the DRS that affect interactions with Lig-D (Figures 4A–4C). For instance, ERK2His123 is rotated by ∼120° in the oxidized structure, bringing its δH within ∼3.0 Å of the εO of C159-SOH. In fact, in some models within the top-ranked cluster, these atoms formed a hydrogen bond (data not shown). Consequently, the loop between strands β7 and β8 is shifted downward, allowing the formation of an H-bond between Lig-DN15 and the backbone carbonyl of ERK2T158. The H-bond between these residues may constrain the peptide backbone, causing Lig-DL14 to be displaced from the φA binding pocket and potentially destabilizing the interaction (Figure 4C). Consistent with this hypothesis, if the H-bonding potential of N15 and ERK2T158 is disrupted by converting N15 to an aspartate residue in Sub-D (i.e., Sub-D(N15D)), no substantial changes in ERK2 activity are observed following H2O2 treatment (Figure 4D).

Mutation of ERK2C159 abolishes H2O2-induced changes in ERK2-Sub-D interactions

Our data suggested that ERK2C159 is sulfenylated at low H2O2 concentrations and that this modification disrupts interactions between ERK2 and the DRS-binding region of Sub-D. Therefore, to further explore the biochemical basis for H2O2-dependent changes in ERK2-Sub-D interactions, we generated a variant of ERK2 in which C159 was mutated to Ser (ERK2(C159S)) and tested both its affinity for Lig-D and its activity toward Sub-D. Though Ser is structurally very similar to Cys, the presence of a hydroxyl group in place of the thiol moiety of Cys effectively prevents Ser from oxidizing. Therefore, we predicted that ERK2(C159S) would not exhibit the same H2O2-induced changes observed for the wild-type (WT) enzyme. Indeed, no change in the affinity of ERK2(C159S) for Lig-D was observed by SPR following H2O2 treatment (Figures 5A and 5B). Likewise, even though the activity of untreated ERK2(C159S) toward Sub-D was almost identical to that of the wild-type (WT) enzyme, the H2O2-dependent increase in Sub-D phosphorylation that we had observed previously with WT ERK2 was largely abolished when the mutant enzyme was analyzed (Figure 5C). Similarly, ERK2(C159S) did not exhibit the same H2O2-dependent changes in Km,app that were observed for WT ERK2 (Figure 5D; Table 1). Interestingly, though not as pronounced as what was observed for the WT enzyme, ERK2(C159S) still exhibited a modest increase in kcat,app following treatment with 2.5 μM H2O2 (8.4 ± 0.9 s−1 vs. 10.7 ± 1.8 s−1) (Table 1). This may suggest that oxidation of other H2O2-sensitive residues could also somewhat affect catalysis. Nonetheless, taken in aggregate, these studies suggest that H2O2-dependent changes in ERK2 activity toward Sub-D are largely due to decreased affinity within the DRS caused by sulfenylation of C159.

Figure 5.

Analysis of ERK2(C159S)-Sub-D interactions

(A) Representative equilibrium binding experiment measuring the affinity of oxidized ERK2(C159S) for Lig-D using surface plasmon resonance imaging (SPRi) at Lig-D concentrations ranging from 1.6 to 100 μM. The binding curve is shown in the inset.

(B) Average KD,app for untreated ERK2(C159S) (blue) and ERK2(C159S) treated with 2.5 μM H2O2 prior to immobilization (red). N = 3 independent experiments repeated in duplicate. Error bars represent standard error about the mean. Statistically significant differences are indicated by an asterisk (∗, p < 0.05); n.s.: no significance.

(C) Relative activity of ERK2(C159S) (orange) and WT ERK2 (blue) toward Sub-D following oxidation of the kinase using the indicated concentrations of H2O2. Data points and error bars are as in Figure 2D. Asterisks indicate p < 0.01.

(D) Steady-state kinetics analysis of ERK2(C159S) vs. Sub-D following pre-treatment of ERK2(C159S) with 2.5 μM H2O2 (orange) or dH2O (green) (n > 3 independent experiments repeated in duplicate). Error bars represent standard error about the mean. No statistically significant differences in v0 were observed between treated and untreated ERK2(C159S) at any of the Sub-D concentrations tested.

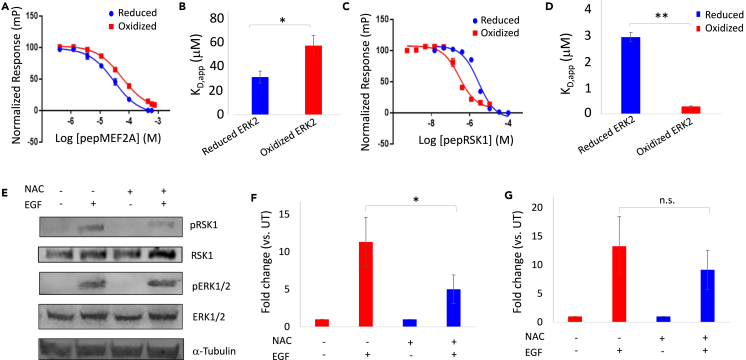

H2O2-dependent oxidation affects ERK2 interactions with other substrates

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that oxidation of C159 could affect ERK2 activity toward different substrates differently depending on the interaction context. For instance, we reasoned that sulfenylation of C159 could prevent ERK2 from interacting with some DRS binding partners (e.g., due to steric clashes, altered DRS architecture, or charge repulsion) while having little effect on others. Similarly, sulfenylation may also promote interactions with substrates that bind the sulfenylated oxoform better than the sulfhydryl moiety on unmodified Cys. Therefore, we asked what impact H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 had on its interactions with other ERK2 substrates. For instance, similar to Lig-D, fluorescence polarization competition assays using a peptide containing the DRS-binding region of the ERK2 substrate myocyte enhancer factor 2A (pepMEF2A) suggest that oxidation of ERK2 with a 7:1 M excess of H2O2 leads to an ∼2-fold increase in its KD,app toward pepMEF2A (Figures 6A and 6B).73,74 In contrast, ERK2’s KD,app toward a peptide containing the DRS-binding region of the MAPK-associated protein kinase, ribosomal S6 kinase A1 (pepRSK1), decreased over 10-fold relative to the untreated control following H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 (Figures 6C and 6D). ERK1/2 is known to phosphorylate RSK1 on T359 in the linker region connecting RSK1’s N- and C-terminal kinase domains (NTKD and CTKD), facilitating the recruitment of phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1) and activation of the NTKD.75 Consistent with the notion that H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 promotes interactions with RSK1, when HeLa cells were preincubated with the cellular reductant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) before stimulation with epidermal growth factor (EGF), we observed a significant decrease in RSK1 phosphorylation (Figures 6E and 6F). Though we also observed a modest decrease in ERK1/2 phosphorylation following NAC treatment, the difference in pERK1/2 levels between untreated and NAC-treated cells was insignificant (Figure 6G). Likewise, control experiments using the MAPK kinase (MAP2K) inhibitor UO126 suggest that EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of RSK1 in HeLa cells depends on the MAPK signaling axis (Figure S4). In contrast, ERK2(C159S) overexpression largely eliminated NAC-induced differences in RSK1 phosphorylation following EGF stimulation (Figure S5). Likewise, no significant change in ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of the F-site substrate, ETS2 repressor factor (ERF), was observed following EGF stimulation in the presence and absence of NAC (Figure S6).76 Though we cannot currently rule out the possibility that the decreased phosphorylation of RSK1 is due to derepression of S/T phosphatase activity in the presence of NAC, these data are consistent with the notion that oxidation of ERK1/2 following EGF stimulation increases its affinity for RSK1, leading to increased RSK1 phosphorylation in cells (it should also be noted that, unlike PTPs, the major S/T phosphatases, PP1, PP2A, and PP2B, appear to be resistant to H2O2-dependent inhibition).77

Figure 6.

H2O2-dependent changes in ERK2 interactions with other substrates

(A) Results of a representative fluorescence polarization (FP) competition assay following incubation of the indicated concentrations of unlabeled pepMEF2A with FITC-pepHePTP and ERK2 that had been pretreated with either a 7-fold molar excess of H2O2 (red squares) or dH2O (blue circles). Error bars represent standard error about the mean of two replicate experiments.

(B) Average apparent KD of oxidized (red) and reduced (blue) ERK2 for pepMEF2A. Error bars represent standard error about the mean of four independent experiments done in duplicate; ∗p < 0.05.

(C) Results of a representative FP competition assay following incubation of unlabeled pepRSK1 with FITC-pepHePTP and ERK2 that had been pretreated with either a 7-fold molar excess of H2O2 (red squares) or dH2O (blue circles). Error bars represent standard error about the mean of two replicate experiments.

(D) Average apparent KD of oxidized (red) and reduced (blue) ERK2 for pepRSK1. Error bars represent standard error about the mean of three independent experiments done in duplicate; ∗∗p < 0.01.

(E) Representative western blot following treatment of HeLa cells with or without 5 mM N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) for 45 min followed by stimulation with epidermal growth factor (EGF) or vehicle alone for 10 min. Lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies.

(F and G) Fold-change in the ratio of pRSK1(T359) to total RSK1 (F) and pERK1/2(T202/Y204) to total ERK1/2 (G) normalized to the untreated control. Error bars represent standard error about the mean of five independent experiments; ∗p < 0.05. See also Figures S4–S7.

Discussion

We have investigated the impact of H2O2-dependent oxidation on the interactions between the canonical MAPK, ERK2, and select ERK2 substrates. These studies revealed that ERK2 is sulfenylated on C159 in its DRS and that this modification differentially alters its activity toward DRS- and FRS-specific substrates. Indeed, biochemical and mutational analysis demonstrated that oxidation of ERK2 decreases its affinity for the model DRS peptide substrate, Sub-D, while simultaneously increasing the substrate’s turnover number. In contrast, oxidation did not affect ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of the F-site peptide substrate, Sub-F. Using fluorescence polarization binding assays, we subsequently found that H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 alters its interactions with the DRS-binding regions of other ERK2 substrates. Interestingly, ERK2 oxidation affected interactions with different D-site ligands differently, leading to both H2O2-dependent increases and decreases in its KD,app depending on the ligand under study. Importantly, cell-based assays demonstrated that oxidation by signal-generated H2O2 can alter ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of the endogenous D-site substrate, RSK1, while having no effect on the phosphorylation status of the Ets domain transcriptional repressor, ERF, which is recognized by ERK1/2 via F-site interactions.76 Likewise, ERK2(C159S) overexpression abolished oxidation-induced changes in RSK1 phosphorylation in situ. Together, these data suggest that redox modification of ERK2 on C159 within its DRS can differentially affect its substrate selection in situ.

Impact of H2O2-dependent oxidation on ERK1/2’s interactions with upstream regulatory factors

Our biochemical and mutational studies suggest that ERK2 is sulfenylated on C159 within the DRS ligand docking region under mildly oxidizing conditions and that this modification alters ERK2 interactions with D-site substrates while having little effect on F-site substrates. Interestingly, ERK1/2 also recognizes several important regulatory factors in addition to its downstream substrates via its DRS.73,74,78,79,80,81 For instance, ERK1/2’s upstream activating MAP2Ks, MEK1 and MEK2, utilize the DRS for binding. As alluded to earlier, the Lig-D binding domain in Sub-D is derived from the yeast MEK1 homolog, STE7.61,68 In this respect, it is important to note that we previously observed sulfenylation of both total and dually phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) in several cell lines.36 In NIH3T3cells, the extent of sulfenylation on pERK1/2 increased shortly after PDGF stimulation and continued to increase for 10 min after that, suggesting that either ERK1/2 is sulfenylated after being phosphorylated by MEK1 or that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 can be sulfenylated. Consistent with the latter, we observed substantial sulfenylation of total ERK1/2 in SK-OV3 ovarian cancer cells, even in unstimulated, serum-starved cells. Interestingly, in these cells, though the extent of sulfenylation observed in total ERK1/2 did not change significantly following lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) treatment, there was a marked increase in pERK1/2 levels (and sulfenylated pERK1/2) shortly after LPA stimulation. Though we cannot exclude the possibility that MEK1/2 preferentially phosphorylates reduced ERK1/2 molecules following LPA stimulation, MEK1/2 can likely phosphorylate both the oxidized and reduced forms of ERK1/2. This is consistent with our ERK2-Lig-D binding experiments, where oxidation decreased ERK2’s affinity for Lig-D but did not abolish it. Taken together, these data suggest that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK1/2 can be sulfenylated in situ and that sulfenylation does not abolish phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by MEK1/2. However, we did not explicitly measure the rate of ERK1/2 phosphorylation during these experiments. Therefore, it will be interesting to see what effect oxidation of ERK1/2 has on its activation profile. To this end, we are currently investigating the impact of ERK2 oxidation on its association with MAP2Ks and its effects on ERK2’s activation kinetics.

Impact of H2O2-dependent oxidation on ERK1/2’s interactions with downstream regulatory factors

Along these same lines, interactions between ERK1/2 and downstream phosphatases, such as protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 7 (PTPN7/HePTP) and dual specificity protein phosphatase 6 (DUSP6/MKP3), also rely on interactions with the DRS.73,74,80,81,82,83 Therefore, oxidation of ERK1/2 may alter interactions with these phosphatases, either positively or negatively. Consistent with this hypothesis, FP binding assays suggest that H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 leads to an ∼100-fold increase in its KD,app for a peptide containing the D-site of HePTP (pepHePTP; Figure S7). This, together with the potential effect on MEK1/2 activation kinetics alluded to above, raises the intriguing possibility that ERK1/2 activation dynamics may be altered during periods of oxidative stress. This is important because several studies suggest that prolonged exposure to oxidizing agents leads to sustained ERK1/2 activation and the induction of apoptosis.84 Therefore, it will be interesting to track spatiotemporal changes in ERK1/2 activity profiles in living cells under oxidizing and reducing conditions using molecular tools such as genetically targetable fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensors.85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92

Conservation of ERK2C159 among MAPK family members

Finally, it is interesting that ERK2C159 is conserved among all MAPK family members (Figure S8). This suggests that redox modification of this site might represent a general strategy to modulate MAPK substrate selection. Consistent with this notion, p38α (MAPK14) is known to be oxidized on C162.35 Our preliminary data suggest that pre-treatment of p38α with H2O2 alters its activity toward Sub-D but not Sub-F. Likewise, we and others have observed H2O2-dependent changes in the activity of JNK family members toward various substrates.25 In the future, it will be interesting to explore the impact of redox modification on the substrate selection of other MAPK family members and kinases from other families (e.g., SRC and EGFR).

In summary, we have explored the hypothesis that oxidation of ERK2 alters its substrate selection. These studies suggest that D- and F-site substrates are differentially phosphorylated following oxidation of ERK2 by H2O2. Biochemical and mutational analyses revealed a plausible mechanism for the observed changes in substrate selection that involves sulfenylation of C159 within ERK2’s DRS ligand binding region. Importantly, the modified Cys residue in ERK2 is highly conserved among other MAPK family members, suggesting that redox modification may be a general mechanism by which the substrate selection of MAPKs is modulated. Together, these studies lay the foundation for examining crosstalk between redox- and MAPK-dependent signaling pathways at the level of substrate selection.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we found that H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 can alter its substrate selection by differentially affecting interactions between ERK2 and its substrates. While computational modeling has provided clues about how H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 could disrupt its interactions with Lig-D, structural studies are necessary both to confirm the predictions and to provide additional molecular details about ERK2-Lig-D interactions in the oxidized and reduced states. Likewise, fluorescence polarization binding assays suggest that H2O2-dependent oxidation of ERK2 affects its interactions with different DRS ligands differently. However, the molecular basis for these changes is not currently clear. Therefore, it will be interesting to examine these interactions in more detail using complementary biochemical, mutational, structural, and computational strategies, in a manner similar to what has been done for Sub-D/Lig-D.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse Anti-ERK1/2 antibody (3A7) | Cell Signaling Technologies | #9107; RRID:AB_10695739 |

| Rabbit anti-phospho-[T183/Y185]-ERK1/2 antibody (197G2) | R&D Biosystems | #AF1018; RRID:AB_354539 |

| Mouse anti-RSK1 antibody | BD Biosciences | #610225; RRID:AB_399695 |

| Rabbit anti-phospho-[T359]-RSK1 antibody | Cell Signaling Technologies | #8753; RRID:AB_2783561 |

| Rabbit anti-ERF(phospho-T526) | Biorbyt | #orb393047 |

| Mouse anti-ERF (33L) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | #sc-130372; RRID:AB_2098313 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| BL21(λDE3) CodonPlus E. coli | Agilent Technologies | Cat#230240 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Sub-D peptide Ac-QRKTLQRRNLKGLNLNL-XXX-TGPLSPGPF-NH2 (where X = 6-aminohexanoic acid) |

Lee et al.61 | Synthesized in-house |

| Sub-F peptide Ac-YAEPLTPRILAKWEWPA-NH2 |

Lee et al.61 | Synthesized in-house |

| Lig-D peptide Ac-FQRKTLQRRNLKGLNLNL-NH2 |

Lee et al.61 | Synthesized in-house |

| Lig-D (N15D) peptide Ac-FQRKTLQRRNLKGLDLNL-NH2 |

This paper | Synthesized in-house |

| Catalase | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C9322 |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | Fisher BioReagents | Cat#BP2633 |

| Dimedone | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#D1553303; CAS: 126-81-8 |

| Iodoacetamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#I1149; CAS: 144-48-9 |

| SCH772984 ERK1/2 selective inhibitor | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S7101 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ADP-Glo assay | Promega | Cat#V6930 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Molecular dynamics simulations of interactions between reduced ERK2 and Lig-D. | This paper | https://figshare.com/s/db5a3019a8667bbc5932 |

| Molecular dynamics simulations of interactions between oxidized ERK2 and Lig-D. ERK2 is sulfenylated on C159. | This paper | https://figshare.com/s/0f997eba6849c87dc772 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| NIH-3T3 (M. musculus, male, embryonic) | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1658; RRID: CVCL_0594 |

| SK-OV3 (H. sapiens, female, 64 years) | ATCC | Cat#HTB-77; RRID: CVCL_0532 |

| HeLa (H. sapiens, female, 31 years) | ATCC | Cat#CCL-2; RRID: CVCL_0030 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| ERK2 (C159S) GeneBlock--WT ERK2 sequence with TCT (Ser) substituted for TGT (Cys) at the C159 codon | Genscript | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid NpT7-5-ERK2 | Robbins et al.93 | Addgene plasmid #39230; RRID:Addgene_39230 |

| Plasmid NpT7-5-ERK2(C159S) | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pcDNA3.1-ERK2(C159S) | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pRSETa-MKK-G7B | Mansour et al.94 | Natalie Ahn (Univ. Colorado at Boulder) |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism v7.0 | GraphPad | Version 7.0 |

| KaleidaGraph v4.5 | Synergy Software | Version 4.5 |

| TraceDrawer 1.11 | Ridgeview Instruments | Version 1.11 |

| Autodock | Morris et al.69 | N/A |

| ChimeraX 1.12 | Pettersen et al.; Univ. California San Francisco 70 | N/A |

| GROMACS | Pronk et al.71 | N/A |

| Proteome Discoverer v1.3 | Thermo Scientific | XCALI-97208 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Robert H. Newman (rhnewman@ncat.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell culture and treatments

Cell lines, along with corresponding Resource Identification Initiative accession numbers and sex, were: HeLa (RRID: CVL-0030; female), NIH3T3 (RRID: CVCL_0594; male), and SK-OV3 (RRID: CVCL_0532; female). All cell lines were obtained from ATCC-derived stocks from the Cell and Viral Vector Laboratory Shared Resource at Wake Forest School of Medicine, where they were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) analysis and verified to be mycoplasm-free. Cells were cultured in either DMEM (NIH3T3 and HeLa) or RPMI (SK-OV3) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2. Unless otherwise indicated, cells were serum starved prior to stimulation by transferring the cells into fresh, serum-free media for 18 h before addition of the stimulus. In the case of NAC treatment, serum-starved HeLa cells were incubated with 5 mM NAC or vehicle alone for 45 minutes prior to stimulation with EGF for 10 minutes. Following stimulation, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Millipore-Sigma) and protease inhibitors (Roche). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 4-15% SURE-PAGE gels before being transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for western blot analysis. To overexpress ERK2(C159S) in HeLa cells, polyethyleneimine (PEI) was used to transfect HeLa cells with a pcDNA3.1 vector encoding ERK2(C159S) under the control of the strong CMV promotor 18-24 hours before serum starvation.

Bacterial expression strain

Recombinant wild-type ERK2 and ERK2(C159S) were expressed in BL21 (λDE3) CodonPlus E. coli (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Transformed bacteria were grown overnight in Luria broth (LB) media supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37°C with vigorous shaking at 200 rpm. The following morning, the culture was sub-cultured into LB and grown to an OD600 between 0.8-1.0 OD. To induce expression of recombinant protein, isopropyl-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 μM, and the culture was incubated at 17°C overnight with vigorous shaking at 200 rpm.

Method details

Reagents and antibodies

ADP-Glo luminescence assay reagents, including ultrapure ATP and ultrapure ADP, were purchased from Promega. Catalase was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, while H2O2 was from Fluka. Mouse anti-ERK1/2 and rabbit anti-RSK1(phospho-T359) were from Cell Signaling Technologies, while mouse anti-RSK1 and rabbit anti-ERK1/2(phospho-T183/Y185) were from BD Biosciences and R&D Biosciences, respectively. Likewise, rabbit anti-ERF(phospho-T526) and mouse anti-ERF antibodies were purchased from Biorbyt and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, respectively. Dimedone and iodoacetamide (IAM) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Lig-D (Ac-FQRKTLQRRNLKGLNLNL-NH2), Sub-D (Ac-QRKTLQRRNLKGLNLNL-XXX-TGPLSPGPF-NH2 where X = 6-aminohexanoic acid), Sub-F (Ac-YAEPLTPRILAKWEWPA-NH2), and Sub-D(N15D) (Ac-QRKTLQRRNLKGLDLNL-XXX-TGPLSPGPF-NH2) peptides were synthesized, essentially as described previously61 and verified by mass spectrometry. The ERK1/2-selective inhibitor, SCH772984, was purchased from Selleck, Inc. (Houston, TX).

Cloning, expression, and purification of ERK2

Plasmid NpT7-5-ERK2, encoding wild-type rat ERK2 under the control of the T7 promotor, was obtained from Addgene (plasmid #39230).93 The ERK2(C159S) variant was generated from a DNA sequence synthesized by Genscript using the same nucleotide sequence as for WT rat ERK2 (in the NpT7 vector), except the C159 codon (TGT) was mutated to TCT (encoding Ser). A DNA fragment from the synthesized construct was generated by restriction digestion with ApaI and NotI and ligated into the same sites of the NpT7 ERK2-expression vector. The resulting plasmid, termed NpT7-5-ERK2(C159S), was verified by restriction digestion and by sequencing of the entire coding region of the construct. To purify the kinase-of-interest, either wild-type ERK2 and ERK(C159S) was expressed in BL21 (λDE3) CodonPlus E. coli and purified essentially as described.93,95,96 Briefly, proteins from bacterial lysates were first loaded onto a cobalt-NTA column (GE Healthcare) that had been preequilibrated in equilibration buffer (Buffer EQ: 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). The column was then washed with 4 column volumes of wash buffer (Buffer W: 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 50 mM Imidizole) before being eluted with 2.5 column volumes of elution buffer (Buffer EL: 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). Fractions containing ERK2 were verified by immunoblot against ERK2 and pooled together, dialyzed into Buffer S (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5 (adjusted at 4°C), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol) and concentrated using 3K MWCO Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (MilliporeSigma). Concentrated ERK2 (either WT or ERK2(C159S)) was then phosphorylated in vitro using a 20:1 molar ratio of ERK2-to-MKK-G7B, a constitutively active form of MEK1, for 6 hours at 30°C in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ATP, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, as described previously.97,94 The MKK-G7B plasmid (in pRSETa) was a kind gift from Natalie Ahn (University of Colorado at Boulder). After in vitro TEY-phosphorylation by MKK-G7B, ERK2 was applied to a 15 mL Source Q column to separate doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 from monophosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK2. Doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 was verified by immunoblot against TEY-phosphorylated ERK2 and by mass spectrometry. Finally, fractions containing doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 were pooled and dialyzed into Buffer S. The concentration was measured spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient (A280) of 52,067 cm-1M-1.98

Identification of redox-sensitive cysteines

Purified ERK2 (15 μM) was treated with 0, 100, 500, or 1000 μM H2O2 (corresponding to H2O2-to-ERK2 molar ratios of ∼7:1, ∼33:1, and ∼67:1, respectively) in the presence of 7 mM dimedone in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 for 1 hour at room temperature. Reactions were quenched by addition of 200 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) at room temperature in the dark for 10 minutes, followed by dilution into 6 M Guanidine-HCl. Denatured protein was incubated under these conditions with 50 mM IAM for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Samples were then precipitated in cold methanol overnight at -20°C. After washing, each sample was resuspended in 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10% acetonitrile and digested by trypsin at 37°C overnight.

Peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS using an Accela Open UPLC system coupled to a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap LTQ XL high-resolution mass spectrometer. Separations were achieved using a Thermo Hypersil GOLD C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) at ambient temperature with a gradient of buffer A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water) and buffer B (100% (v/v) methanol and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid) at a flow rate of 250 μl/min. Peptides were separated using a gradient elution of 5–95% (v/v) B over 18 minutes, holding at 100% B for 2 min, followed by a 2-minute wash at 100% B. The gradient was then decreased to 5% B over 0.1 minute and held at 5% B for 4.9 minutes for a total run time of 25 minutes. Eluant was introduced to the mass spectrometer via positive electrospray ionization with the following settings: sheath gas of 65, source voltage of 4.0 kV, capillary temperature of 325°C, capillary voltage of 38.5 V, and tube lens held at 68.0 V. The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent acquisition mode using Xcalibur v1.3 (Thermo Scientific). After a full scan (200–2000 m/z range) at high resolution (60,000), the top five most intense precursor ions were isolated and fragmented using collision-induced dissociation with the normalized collision energy set at 35%, activation Q at 0.25, and activation time at 30 ms. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat duration and exclusion duration of 30 s.

MS spectra were searched using the SEQUEST search algorithm with Proteome Discoverer v1.3 (Thermo Scientific) against the sequence for recombinant His-tagged rat ERK2. Search parameters were as follows: FT-trap instrument, parent mass error tolerance of 10 ppm, and fragment mass error tolerance of 0.8 Da (monoisotopic) with variable modifications that included methionine oxidation, cysteine iodoacetamide products, cysteine dimedone products, and cysteine dioxidation.

Non-reducing SDS-PAGE of purified ERK2

To determine whether recombinant ERK2 forms intramolecular and/or intermolecular disulfide bonds in vitro under our experimental conditions, ERK2 was treated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature. Excess H2O2 was then removed by incubation with catalase for 1 minute before the reaction was quenched by the addition of 6X SDS loading buffer containing either 10 mM DTT (i.e., reducing) or no reducing agent (i.e., non-reducing). Samples were then incubated at 95°C for 5 minutes before being resolved by SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, gels were analyzed by western blotting using anti-ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies).

Non-reducing SDS-PAGE of endogenous ERK1/2

To determine whether endogenous ERK1/2 forms intramolecular and/or intermolecular disulfide bonds following oxidation by signal-generated H2O2, serum-starved SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells, NIH3T3 fibroblasts, and HeLa cells were treated with either 100 nM LPA, 20 ng/mL PDGF, or 100 ng/mL EGF, respectively, for the indicated times, as described.36 Cells were then harvested in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 100 μM diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA), 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100 supplemented with freshly prepared 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 mM Sodium vanadate (Na3VO4), and 10 mM Sodium fluoride (NaF)) and total protein content quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal quantities of protein were denatured in 6X SDS loading buffer containing either 10 mM DTT (i.e., reducing) or no reducing agent (i.e., non-reducing), incubated at 100°C for 5 minutes, then resolved by SDS-PAGE on 10% PAGE gels. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Life Sciences), which was then blocked with 5% powdered milk in TBST and immunoblotted for total ERK1/2 using the anti-ERK1/2 primary antibody.

Monobromobimane assay

To determine the pKa of the reactive Cys residue in ERK2, purified ERK2 (4 μM) was incubated with 32 μM monobromobimane in 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH ranging from 2.2 - 7.4 for 60 minutes.27,99 After incubation, fluorescence of the thioether product was measured (Ex: 395 nm; Em: 475 nm). The average background-corrected fluorescence intensity (F-F0) in arbitrary units (AU) was plotted versus pH. The approximate pKa of the reactive C159 was determined using non-linear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism.

Trans-phosphorylation assays

For trans-phosphorylation assays, doubly-phosphorylated ERK2 was diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) to 465 nM before being treated with either deionized water (dH2O) or the indicated concentration of H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature. The concentration of ERK2 during peroxide treatment was 387.5 nM. Excess H2O2 was then scavenged by the addition of 1 U of catalase at room temperature for 1 minute. ERK2 was further diluted into Kinase Buffer A (2 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7.2, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM EGTA, 0.16 mM EDTA, 16 ng/μL BSA, 1.6% (w/v) glycerol, 20 μM ATP) supplemented with the substrate-of-interest (i.e., either Sub-D, Sub-F, or Sub-D(N15D)) at a final concentration of 1 μM. Sub-D is a modular peptide composed of Lig-D, which is derived from the DRS-binding region of the yeast MAP2K STE7, linked to a MAPK consensus phosphorylation site via a short 6-aminohexanoic acid linker.61 Meanwhile, Sub-F consists of a C-terminal FRS-binding region separated by five amino acids from a consensus MAPK substrate motif. The final concentration of ERK in the trans-phosphorylation reaction was 89 nM. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes before quenching the reaction with the ERK1/2 selective inhibitor, SCH772984. The extent of ERK-mediated phosphorylation was then assessed using the ADP-Glo luminescence assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, an equivalent volume of ADP-Glo reagent was added to each quenched trans-phosphorylation reaction and incubated at room temperature for 40 minutes at room temperature to deplete all remaining ATP.100 The ADP produced by ERK2-mediated phosphorylation of the substrate-of-interest was then converted to ATP by adding an equivalent volume of Kinase Detection Reagent and incubating for an additional 40 minutes at room temperature. Finally, luminescence was detected using an Infinite F500 microplate reader (Tecan, USA). Each set of reactions included a negative control in which TBS vehicle was substituted for ERK2. To determine the amount of ATP consumed during the trans-phosphorylation reaction, a standard curve was generated by measuring the luminescence of solutions with known ratios of ultrapure ATP and ultrapure ADP nucleotide concentrations used in the assay. All responses were background corrected by subtracting the negative control response and then normalized to the untreated control (i.e., ERK2 treated with dH2O). Control experiments verified that preincubation with H2O2, followed by removing excess peroxide by catalase, did not affect the ADP-Glo assay.

Steady-state kinetic analysis

During steady-state kinetic analysis, we mirrored the conditions used during the titration experiments. Briefly, the 387.5 nM of the kinase-of-interest (e.g., ERK2 or ERK2(C159S)) was pre-incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes with either dH2O (untreated) or 2.5 μM of H2O2 before excess H2O2 was removed by treatment with catalase for 1 minute. The treated kinase was then diluted in Kinase Reaction Buffer A containing the indicated substrate concentrations and incubated for 30 minutes at 30°C. To assess the impact of H2O2-dependent oxidation on ERK2’s interactions with Sub-D, the concentration of Sub-D was varied while holding ATP constant at 20 μM. Likewise, to assess the effect of oxidation on ERK2-ATP interactions, Sub-D was held constant at 1 μM while varying ATP levels. At the end of the experiment, the kinase activity was quenched by adding the ERK2-selective inhibitor, SCH772984, and the activity was measured using the ADP-Glo luminescence assay, as described above. Under these conditions, control experiments verified that <10% of the total substrate was consumed by the reaction, suggesting that the steady-state assumption was valid. The initial velocity (v0) was then plotted versus substrate concentration and the kinetic parameters, Vmax and Km, were determined by non-linear regression analysis using the Michaelis-Menten model in GraphPad Prism 7.0 (San Diego, CA). The apparent catalytic rate constant, kcat,app, was determined by dividing Vmax by the enzyme concentration during the reaction (i.e., 89 nM).

Surface plasmon resonance

To determine the effect of H2O2-dependent oxidation of wild-type ERK2 or ERK2(C159S) on its affinity for the DRS-specific ligand, Lig-D, interactions between immobilized ERK2 and Lig-D were investigated by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) using an OpenSPR-XT system (Nicoya Life Sciences, Kitchener, Ontario, CAN). To this end, 349 nM ERK2 was pre-incubated with either dH2O or 2.44 μM H2O2 (∼7:1 H2O2:ERK2 ratio) for 10 minutes at room temperature before excess H2O2 was removed by treatment with catalase for 1 minute at room temperature. The kinase was then immobilized to 1000-3000 response units (RU) on a Ni-NTA sensor equilibrated in degassed running buffer (20 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.005% Nonidet P-40) at a flowrate of 10 μL/min.101 Following ERK2 immobilization, increasing Lig-D (ranging from 1.5625-100 μM) diluted in running buffer were applied to the sensor surface at a flowrate of 20 μL/min. At the end of each injection, running buffer was applied for an additional 600 seconds (10 minutes) to allow Lig-D to dissociate from the immobilized ERK2. At all Lig-D concentrations tested, the signal returned to baseline before the next injection, suggesting that Lig-D had completely dissociated from ERK2 during the dissociation phase. At the beginning, middle, and end of each set of injections, buffer alone was injected to determine the background response. Each injection was repeated in duplicate. The resulting sensograms were background corrected and analyzed using the “Affinity/EC50” function in TraceDrawer analysis software (Ridgeview Instruments, Upsalla, Sweden).

Molecular modeling of ERK2-Lig-D interactions

The molecular modeling program, Autodock, was used to model interactions between Lig-D and either the reduced form of ERK2 or ERK2 that has been sulfenylated at C159 (ERK2(C159-SO)).69 To generate ERK2(C159-SO), the sulfhydryl group on C159 of ERK2 (PDB: 2ERK) was first converted to sulfenic acid and then the Lig-D peptide (adopted from PDB: 2B9H with modifications) was introduced into the structure for docking. The initial coordinate of Lig-D in the docking was decided based on the position of the STE7 peptide bound to the yeast ERK2 ortholog, FUS3. Lig-D was treated as semi-rigid with most of the side chains flexible while ERK2 structures were treated as rigid. A fairly large gridbox (74x74x74 Å) was created to give enough space to search favorable interactions between Lig-D and ERK2. Docking was performed with a medium level of maximum number of energy evaluations and 50 genetic algorithm runs were completed. Images were generated using ChimeraX 1.12. Finally, after docking, the top-ranked models were refined by MD simulations using GROMACS.71 The fidelity of the models generated during molecular dynamics simulations were evaluated based on several criteria, including reproducibility across multiple models, energetics, and consistency with existing biochemical data.

Fluorescence polarization binding assays

The affinity of oxidized and reduced forms of ERK2 for select ligands was determined using a fluorescence polarization (FP) binding assay essentially as described by Garai et al.74 Briefly, the affinity of oxidized and reduced forms of ERK2 for FITC-labeled pepHePTP (FITC- RLQERRGSNVALMLDV) was first determined by incubating various concentrations of ERK2, ranging from 0.16 nM to 82.5 μM ERK2, with 1 nM FITC-pepHePTP for 30 minutes at room temperature in FP binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05% Brij-35 supplemented with fresh 2 mM DTT when measuring the binding of reduced ERK2 and no reducing agent when measuring the binding of oxidized ERK2). Fluorescence polarization was measured in a 384-well black-walled plate using an Infinite F500 PRO multimodal microplate reader (Tecan, Inc.). The resulting binding curves were fit using non-linear regression analysis using the “log-agonist vs. normalized response—variable slope” module in GraphPad Prism 7.0. After determining the affinity of oxidized and reduced ERK2 for FITC-pepHePTP, the affinities of unlabeled ligands were determined using a steady-state competition assay where 1 nM FITC-pepHePTP was first incubated with a concentration of oxidized or reduced ERK2 sufficient to achieve 60-80% binding. Subsequently, increasing concentrations of unlabeled ligand were added and FP was measured as described for the direct binding assays. The KD for each ERK2-ligand interaction was determined by fitting the resulting binding curve using the ”One Site-Fit Ki” module in GraphPad Prism 7.0 (please note that, in the competition assays, the interaction profiles are based on Ki values because the assay is designed to measure the extent to which the unlabeled ligand inhibits the binding of the FITC-pepHePTP to oxidized and reduced forms of ERK2). All FP binding assays were duplicated, with at least three independent sets of experiments per condition.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

Statistical details of experiments are included in the figure legends. Unless stated otherwise, all data points represent the mean ± standard error. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s unpaired t-test in MS Excel, assuming a two-tailed distribution. P-values that were <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grants 5SC2GM113784 and 1SC1GM130545 (to R.H.N.), 1SC2GM139698 (to M.D.), R01GM119227 and R35GM135179 (to L.B.P.), R01GM123252 and R01CA262670 (to K.N.D.) as well as P30CA012197 to (D.P.) and T32AI007401 (to J.D.K.) and Wake Forest Center for Molecular Signaling support (to J.D.K.).

Author contributions

A.E.P. and L.L.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and helped write the manuscript; E.S.E., A.E.O., S.P., A.S.P., M.C., and A.K. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data; W.A.L., O.T., and A.J.W. synthesized, purified, and characterized peptides (i.e., Sub-D, Sub-D (N15D), Sub-F, and Lig-D); T.S.K. helped with BI-78D3 experiments; D.P., A.E.P., and L.L.A. expressed and purified ERK2 and ERK2(C159S); K.J.N. conducted mass spectrometry experiments; J-S.J. conducted experiments, analyzed data, and helped with manuscript development; M.D. and D.B.K. conducted computational modeling experiments and molecular dynamics simulations and helped with manuscript development; J.N. and H.Z. helped with manuscript development; C.M.F. helped guide mass spectrometry experiments and manuscript development; K.N.D. helped with computational modeling experiments, BI-78D3 experiments, and manuscript development; L.B.P., J.D.K., and R.H.N. conceived the project, designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

L.B.P. and C.M.F. are cofounders of Xoder Technologies, LLC, through which chemical probes to assess protein oxidation are available. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in their field of research or within their geographical location. One or more of the authors of this paper received support from a program designed to increase minority representation in their field of research.

Published: September 2, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107817.

Contributor Information

Leslie B. Poole, Email: lbpoole@wakehealth.edu.

Jeremiah D. Keyes, Email: jkeyes@psu.edu.

Robert H. Newman, Email: rhnewman@ncat.edu.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Data are freely available at Figshare (www.figshare.org) and can be accessed for review at the following sites: https://figshare.com/s/0f997eba6849c87dc772 (molecular dynamics simulations of sulfenylated ERK2-Lig-D); and https://figshare.com/s/db5a3019a8667bbc5932 (molecular dynamics simulations of reduced ERK2-Lig-D). This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Brown D.I., Griendling K.K. Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:1239–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gostner J.M., Becker K., Fuchs D., Sucher R. Redox regulation of the immune response. Redox Rep. 2013;18:88–94. doi: 10.1179/1351000213Y.0000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gough D.R., Cotter T.G. Hydrogen peroxide: a Jekyll and Hyde signalling molecule. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e213. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison I.P., Selemidis S. Understanding the biology of reactive oxygen species and their link to cancer: NADPH oxidases as novel pharmacological targets. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014;41:533–542. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klomsiri C., Karplus P.A., Poole L.B. Cysteine-based redox switches in enzymes. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011;14:1065–1077. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marinho H.S., Real C., Cyrne L., Soares H., Antunes F. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2014;2:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miki H., Funato Y. Regulation of intracellular signalling through cysteine oxidation by reactive oxygen species. J. Biochem. 2012;151:255–261. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole L.B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;80:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travasso R.D.M., Sampaio Dos Aidos F., Bayani A., Abranches P., Salvador A. Localized redox relays as a privileged mode of cytoplasmic hydrogen peroxide signaling. Redox Biol. 2017;12:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klomsiri C., Rogers L.C., Soito L., McCauley A.K., King S.B., Nelson K.J., Poole L.B., Daniel L.W. Endosomal H2O2 production leads to localized cysteine sulfenic acid formation on proteins during lysophosphatidic acid-mediated cell signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;71:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lugrin J., Rosenblatt-Velin N., Parapanov R., Liaudet L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biol. Chem. 2014;395:203–230. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgoyne J.R., Madhani M., Cuello F., Charles R.L., Brennan J.P., Schröder E., Browning D.D., Eaton P. Cysteine redox sensor in PKGIa enables oxidant-induced activation. Science. 2007;317:1393–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.1144318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgoyne J.R., Oka S.i., Ale-Agha N., Eaton P. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling by protein kinases in the cardiovascular system. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013;18:1042–1052. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devarie-Baez N.O., Silva Lopez E.I., Furdui C.M. Biological chemistry and functionality of protein sulfenic acids and related thiol modifications. Free Radic. Res. 2016;50:172–194. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1090571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hempel N., Melendez J.A. Intracellular redox status controls membrane localization of pro- and anti-migratory signaling molecules. Redox Biol. 2014;2:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole L.B., Nelson K.J. Discovering mechanisms of signaling-mediated cysteine oxidation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J., Wang X., Vikash V., Ye Q., Wu D., Liu Y., Dong W. ROS and ROS-Mediated Cellular Signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016;2016:4350965. doi: 10.1155/2016/4350965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng J., Hotard A.L., Currier M.G., Lee S., Stobart C.C., Moore M.L. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Attachment Glycoprotein Contribution to Infection Depends on the Specific Fusion Protein. J. Virol. 2016;90:245–253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02140-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins J.A., Wood S.T., Bolduc J.A., Nurmalasari N.P.D., Chubinskaya S., Poole L.B., Furdui C.M., Nelson K.J., Loeser R.F. Differential peroxiredoxin hyperoxidation regulates MAP kinase signaling in human articular chondrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;134:139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corcoran A., Cotter T.G. Redox regulation of protein kinases. FEBS J. 2013;280:1944–1965. doi: 10.1111/febs.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditch S., Paull T.T. The ATM protein kinase and cellular redox signaling: beyond the DNA damage response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012;37:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dustin C.M., Heppner D.E., Lin M.C.J., van der Vliet A. Redox regulation of tyrosine kinase signalling: more than meets the eye. J. Biochem. 2020;167:151–163. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvz085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannoni E., Taddei M.L., Chiarugi P. Src redox regulation: again in the front line. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heppner D.E., van der Vliet A. Redox-dependent regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Redox Biol. 2016;8:24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson K.J., Bolduc J.A., Wu H., Collins J.A., Burke E.A., Reisz J.A., Klomsiri C., Wood S.T., Yammani R.R., Poole L.B., et al. H2O2 oxidation of cysteine residues in c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 (JNK2) contributes to redox regulation in human articular chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:16376–16389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piwkowska A. Role of Protein Kinase G and Reactive Oxygen Species in the Regulation of Podocyte Function in Health and Disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017;232:691–697. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truong T.H., Ung P.M.U., Palde P.B., Paulsen C.E., Schlessinger A., Carroll K.S. Molecular Basis for Redox Activation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Kinase. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016;23:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wani R., Qian J., Yin L., Bechtold E., King S.B., Poole L.B., Paek E., Tsang A.W., Furdui C.M. Isoform-specific regulation of Akt by PDGF-induced reactive oxygen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10550–10555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011665108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y., Hu X., Liu Y., Dong S., Wen Z., He W., Zhang S., Huang Q., Shi M. ROS signaling under metabolic stress: cross-talk between AMPK and AKT pathway. Mol. Cancer. 2017;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0648-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphries K.M., Juliano C., Taylor S.S. Regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity by glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43505–43511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kambe T., Song T., Takata T., Hatano N., Miyamoto Y., Nozaki N., Naito Y., Tokumitsu H., Watanabe Y. Inactivation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I by S-glutathionylation of the active-site cysteine residue. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2478–2484. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takata T., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y. 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase 1 is inhibited by S-glutathionylation of its active-site cysteine residue during oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1681–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heppner D.E., Dustin C.M., Liao C., Hristova M., Veith C., Little A.C., Ahlers B.A., White S.L., Deng B., Lam Y.W., et al. Direct cysteine sulfenylation drives activation of the Src kinase. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4522. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06790-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoo S.K., Starnes T.W., Deng Q., Huttenlocher A. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature. 2011;480:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Templeton D.J., Aye M.S., Rady J., Xu F., Cross J.V. Purification of reversibly oxidized proteins (PROP) reveals a redox switch controlling p38 MAP kinase activity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]