Abstract

Parasitic nematodes infect and cause morbidity in over one billion people worldwide, with current anthelmintic drugs decreasing in efficacy. To date, nematodes produce more types of neuropeptides than any other animal. We are interested in the role of neuropeptide signaling systems as a possible target for new anthelmintic drugs. Although FMRFamide-related peptides are found throughout the animal kingdom, the number of these peptides in nematodes greatly exceeds that of any other phylum. We are using Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for examining FMRFamide-like peptides, all of which share a C-terminal Arg-Phe-amide and which are known as FLPs in nematodes. Our previous work indicated interactions between the daf-10 , tax-4 , and flp-1 signaling pathways. In this paper, we further explore these interactions with chemotaxis and dispersal assays.

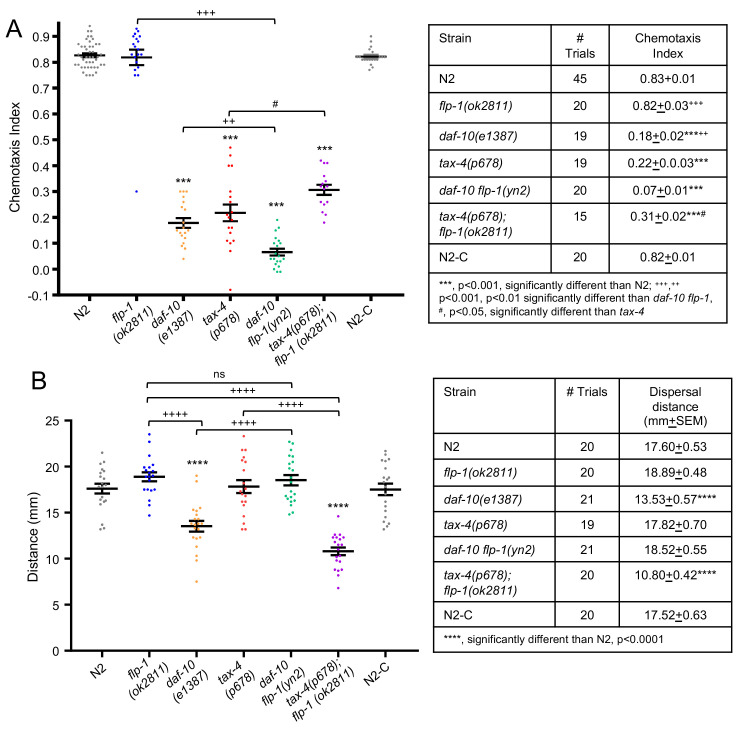

Figure 1. flp-1 signaling is not required for chemosensation, but its signaling can affect the chemosensory and dispersal responses .

Similar to wild type, flp-1 mutants chemotax towards benzaldehyde (A) and disperse in the absence of food (B). However, loss of flp-1 enhances or slightly suppresses the chemosensory defects of daf-10 and tax-4 mutants, respectively (A)(***, p<0.001, significantly different than N2 ; +++ , ++ p<0.001, p<0.01 significantly different than daf-10 flp-1 , # , p<0.05, significantly different than tax-4 ) . By contrast, loss of flp-1 suppresses or causes dispersal defects in daf-10 or tax-4 mutants, respectively (B) (****, p<0.0001, significantly different than N2 , ++++, p<0.0001). Methods: Chemotaxis assays were performed and the chemotaxis index was calculated as described (Bargmann & Horvitz, 1991); each trial had at least 60 animals. For the dispersal assay, L4 animals were picked for use the following day. Six 1-day adults were transferred to a plate without food before transferring to a new plate without food; the locations of the six animals after 15 min were averaged for each plate and constituted one trial. The phenotypes were unknown to the scorers on the chemotaxis and dispersal assays. An unknown, which corresponded to N2 (N2-C), was included in all assays.

Description

An estimated 1.5 billion people, comprising 24% of the world’s population, are infected with soil-transmitted helminths (World Health Organization; Gang & Hallem, 2016). Parasitic nematodes also adversely affect livestock (Whittaker et al., 2017; Strydom et al., 2023) and crops (Sikora et al., 2023) . Of the existing eight classes of anthelmintic therapies, resistance to three classes of anthelmintics have cropped up in livestock (Shalaby, 2013; Abongwa et al., 2017) , suggesting that resistance in humans will soon follow, such as has been found with ivermectin (Weeks et al., 2018; Hahnel et al., 2020; Panda et al., 2022) . These twin challenges, anthelmintic resistance and changing disease patterns, strongly require the need for new anthelmintic therapies.

One possible target for new anthelmintic therapies are neuropeptides and their signaling pathways. Neuropeptides are neuromodulators that influence the strength of synaptic activity. They are derived from large precursor molecules, which undergo post-translational cleavage and modifications in dense core vesicles to form active peptides, whose release can occur at synaptic and extra-synaptic sites. Nematodes contain a significantly larger number of neuropeptides than mammals (Li & Kim, 2014) . The significance of this diverse variety of nematode neuropeptides is still unclear; however, this diversity of neuropeptides provides the animals with a rich peptide toolbox to affect synaptic activity and, ultimately, behavior. Roughly one quarter of all nematodes are parasitic nematodes, an equal number of which infect animals or plants (Al-Banna & Gardner, 2022) . Understanding the functions of these nematode neuropeptides may provide insights into understanding the behavior of parasitic nematodes and into their control.

Although the synaptic connectivity of all neurons within the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been determined (White et al., 1986) , this information only includes direct synaptic connections and gap junctions. The complete connectome, one which also includes extra-synaptic connections, is slowly being elucidated. The task, however, is complicated by the modulatory and overlapping functions of neuropeptides. For instance, a large family of FMRFamide-like peptides, all of which share a C-terminal Arg-Phe-amide, is present in C. elegans ; these peptides are collectively referred to as the FLPs. Each flp gene encodes a unique set of peptide(s). The flp-1 gene encodes multiple peptides that share a C-terminal FLRFamide (Rosoff et al, 1992) . The gene is alternatively spliced and expressed in few neurons (Rosoff et al., 1992; Nelson et al., 1998) . Loss of different FLP-1 peptides results in several behavioral phenotypes, such as defects in locomotion, nose touch sensitivity, and egg laying (Nelson et al., 1998; Waggoner et al., 1998; Buntschuh et al., 2018) .

The double mutant of daf-10 flp-1 ( yn2 ) shows an extreme wandering behavior, which is a synthetic phenotype due to the loss of the two genes; loss of either flp-1 or daf-10 alone does not cause this wandering phenotype (Nelson et al., 1998; Buntschuh et al., 2018) . The flp-1 gene lies within the first intron of daf-10 ; the yn2 deletion removes sequences between introns 1 and 2 of daf-10 and exons 1-3 and part of exon 4 of flp-1 (Buntschuh et al., 2018) . daf-10 encodes a component of the intraflagellar transport complex A, which is necessary for sensory reception of ciliated sensory neurons (Bell et al., 2006) . Loss of both flp-1 and tax-4 , which encodes a subunit of a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel homologous to the vertebrate rod photoreceptor cGMP-gated channel (Komatsu et al., 1996) , also caused a wandering phenotype, although not as severe as that of the daf-10 flp-1 double mutant (Buntschuh et al., 2018) . We wondered whether the synthetic wandering defect occurred because flp-1 mutants have a chemosensory defect, which enhances the chemosensory defect of daf-10 and tax-4 mutants, thereby causing them to wander.

To assess chemosensation in the different strains, we performed assays with the chemoattractant benzaldehyde (Bargmann et al., 1993) . As previously reported, daf-10 and tax-4 mutants showed severe, but not total loss of chemotaxis, because of a lack of sensory perception via the ciliated neurons in daf-10 mutants or loss of downstream receptor signaling in response to the benzaldehyde odorant in tax-4 mutants ( Fig. 1A ) (Albert et al., 1981; Komatsu et al., 1996; Bell et al., 2006) . Residual chemotaxis response in daf-10 and tax-4 mutants suggests that a secondary pathway allows for a minimal benzaldehyde response ( Fig. 1A ). flp-1 mutants showed no chemotaxis defect to benzaldehyde and performed comparably to wild-type animals ( Fig. 1A ). Hence, we expected that the double mutants, daf-10 flp-1 and tax-4 ; flp-1 , would show decreased chemotaxis responses similar to the daf-10 and tax-4 single mutants. Instead, we found that the daf-10 flp-1 double mutant showed more severe chemotaxis defects than daf-10 mutants alone ( Fig. 1A ), suggesting that activity from a FLP-1 circuit can affect the chemotaxis circuit. By contrast, the tax-4 ; flp-1 double mutants showed slightly better chemotaxis relative to tax-4 mutants alone ( Fig. 1A ), suggesting that an alternative pathway that is inhibited by the FLP-1 circuit is employed.

In the absence of food, C. elegans undergoes two successive behaviors: if the period of starvation is short (e.g., less than 10 minutes), animals will show localized search behavior for food; after 10 minutes, animals begin to show dispersal behavior, whereby animals make less turns, allowing them to move forward for longer runs (Gray et al., 2005) . Inactivation of the AVK interneurons, which release FLP-1 peptides, results in localized searching behavior, suggesting that tonic release of FLP-1 peptides from the AVK neurons is necessary for dispersal behavior (Oranth et al., 2018) . We examined dispersal behavior in the different strains to determine whether this could explain the wandering phenotype. Using a modified dispersal assay, we found that flp-1 mutants dispersed in search of food similar to wild-type animals ( Fig. 1B ). By contrast, daf-10 mutants had a significantly reduced dispersal compared to wild type ( Fig. 1B ). This decreased dispersal was suppressed in a flp-1 mutant background ( Fig. 1B ), suggesting that a FLP-1 signaling circuit over-rides the sluggish sensory response of daf-10 mutants. Surprisingly, although flp-1 and tax-4 mutants had similar dispersal rates as wild type ( Fig. 1B ) (Oranth et al., 2018) , the double tax-4 ; flp-1 mutant shows a severely compromised dispersal defect ( Fig. 1B ).

Discussion

flp-1 encodes multiple peptides of the FLRFamide family and is the only flp gene that has been found in all parasitic and non-parasitic nematodes to date (Li & Ki, 2014) . Loss of flp-1 causes several defects, including locomotory and reproductive defects (Nelson et al., 1999; Buntschuh et al., 2018) . In particular, flp-1 mutants are hyperactive with an exaggerated waveform, suggesting that the normal function of flp-1 signaling is to inhibit locomotory and waveform circuits, which are the output of integrating multiple environmental cues. Loss of flp-1 and daf-10 or tax-4 leads to a synthetic wandering phenotype, which we suggested may be due to loss of chemosensory responses in flp-1 mutants. While loss of daf-10 or tax-4 causes chemotaxis defects, loss of flp-1 had no effect on the chemotaxis response. By contrast, loss of flp-1 in daf-10 and tax-4 mutants enhanced or partially suppressed the chemotaxis effects, respectively. daf-10 is expressed in all amphidial, phasmid, cephalic, labial, mechanosensory, and BAG neurons (Perkins et al., 1986; Starich et al., 1995) , whereas tax-4 is expressed in a subset of the amphidial neurons as well as the BAG, AUA, and URX neurons (Komatsu et al., 1996) . Hence, chemosensation of other chemicals and osmolarity responses are present in tax-4 mutants, but not in daf-10 mutants. We suggest that when flp-1 is knocked out in an animal with severe sensory defects, such as daf-10 mutants, these double mutants are hyperactive and will travel in a random, non-directed migration pattern, resulting in a low chemotaxis index ( Fig. 1A ). In tax-4 mutants, however, some sensory responses are still present, driving a slightly larger number of tax-4 ; flp-1 double mutants to the odorant than tax-4 mutants alone.

In the absence of food for extended periods (e.g., over 10 minutes), wild-type animals switch from localized search forays for food to longer runs with less turns, a behavior called dispersal (Gray et al. 2005) . daf-10 mutants did not disperse in the absence of food ( Fig. 1B ), perhaps because of its compromised sensory response. However, tax-4 mutants also have a compromised sensory response, yet they dispersed similar distances as wild type ( Fig. 1B ), as other researchers have reported (Oranth et al., 2018) . Although flp-1 mutants are hyperactive, they did not disperse significantly further than wild type, suggesting that speed and dispersal are unlinked. daf-10 flp-1 mutants were able to disperse, suggesting that daf-10 mutants are able to disperse when a flp-1 - mediated inhibition is lifted. We suggest that the lack of dispersal when AVK was optogenetically inhibited was not due to lack of FLP-1 peptide release, but the lack of release of a different neuropeptide expressed in AVK (Taylor et al., 2021) . Perhaps FLP-1 peptides act to inhibit release of this dispersal neuropeptide(s) or the levels of the dispersal neuropeptide(s) rise during starvation to over-ride the inhibitory activity of the FLP-1 peptides.

Although flp-1 and tax-4 single mutants did not have a dispersal defect, the tax-4 ; flp-1 double mutants had a dispersal defect and remained in a dwelling state. Dispersal behavior is the result of several factors, including food scarcity and population density. Hence, the dispersal is an integration of many sensory cues, such as olfactory, gustatory, mechanosensory, pheromone, etc., that eventually lead to a motor response. Chemosensors, which detect immediate food deprivation, are dependent on tax-4 signaling (Komatsu et al., 1996; Coates & deBono, 2002) , whereas prolonged starvation is more dependent on mechanosensation and other signaling pathways (Oranth et al., 2018) . Both of these pathways feed onto the AVK circuit (White et al., 1986) . We suggest that FLP-1 peptides are involved in dispersal activity through a second mechanism, perhaps through effects on PDE. We propose that during starvation, FLP-1 peptides can inhibit PDE activity so that dispersal behavior is promoted. In the tax-4 ; flp-1 double mutants, the lack of sensory signaling and the lack of PDE inhibition decreases dispersal rates.

Methods

Strains. C. elegans strains were grown and maintained at 20°C according to Brenner (1974). The wild-type strain used was N2 var. Bristol. Mutations used are as described in Wormbase (www.wormbase.org) and Buntschuh et al. (2018): LGIII: tax-4 ( p678 ) ; LGIV: flp-1 ( ok2811 ), daf-10 ( e1387 ), daf-10 flp-1 ( yn2 ) .

Chemotaxis index (CI) assays. Assays with a minimum of 60 worms each were conducted as described (Bargmann and Horvitz, 1991) . At least 15 trials were performed for each strain.

Dispersal assays. Fourth stage larval animals were picked for use the following day. 1-day adults were transferred to a plate without food; six animals were then transferred to the test plate, which had no food. The distance each animal traveled after 15 min were averaged and considered one trial. At least 19 trials were conducted for each strain.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Li lab members, past and present, for helpful advice and discussions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH R21AG065890.

References

- Abongwa M, Martin RJ, Robertson AP. A BRIEF REVIEW ON THE MODE OF ACTION OF ANTINEMATODAL DRUGS. Acta Vet (Beogr) 2017 Jun 26;67(2):137–152. doi: 10.1515/acve-2017-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Banna L, Gardner SL. 2022. The phylum Nemata. In Reference Module in Life Sciences. Elsevier, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-822562-2.00028-1

- Albert PS, Brown SJ, Riddle DL. Sensory control of dauer larva formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol. 1981 May 20;198(3):435–451. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Horvitz HR. Control of larval development by chemosensory neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1991 Mar 8;251(4998):1243–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.2006412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell. 1993 Aug 13;74(3):515–527. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80053-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell LR, Stone S, Yochem J, Shaw JE, Herman RK. The molecular identities of the Caenorhabditis elegans intraflagellar transport genes dyf-6, daf-10 and osm-1. Genetics. 2006 Apr 30;173(3):1275–1286. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974 May 1;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntschuh I, Raps DA, Joseph I, Reid C, Chait A, Totanes R, Sawh M, Li C. FLP-1 neuropeptides modulate sensory and motor circuits in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2018 Jan 2;13(1):e0189320–e0189320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates JC, de Bono M. Antagonistic pathways in neurons exposed to body fluid regulate social feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2002 Oct 31;419(6910):925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang SS, Hallem EA. Mechanisms of host seeking by parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2016 May 17;208(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JM, Hill JJ, Bargmann CI. A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Feb 2;102(9):3184–3191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409009101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahnel SR, Dilks CM, Heisler I, Andersen EC, Kulke D. Caenorhabditis elegans in anthelmintic research - Old model, new perspectives. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2020 Oct 2;14:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Mori I, Rhee JS, Akaike N, Ohshima Y. Mutations in a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel lead to abnormal thermosensation and chemosensation in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996 Oct 1;17(4):707–718. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Kim K. Family of FLP Peptides in Caenorhabditis elegans and Related Nematodes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014 Oct 14;5:150–150. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LS, Rosoff ML, Li C. Disruption of a neuropeptide gene, flp-1, causes multiple behavioral defects in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1998 Sep 11;281(5383):1686–1690. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oranth A, Schultheis C, Tolstenkov O, Erbguth K, Nagpal J, Hain D, Brauner M, Wabnig S, Steuer Costa W, McWhirter RD, Zels S, Palumbos S, Miller Iii DM, Beets I, Gottschalk A. Food Sensation Modulates Locomotion by Dopamine and Neuropeptide Signaling in a Distributed Neuronal Network. Neuron. 2018 Nov 1;100(6):1414–1428.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins LA, Hedgecock EM, Thomson JN, Culotti JG. Mutant sensory cilia in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1986 Oct 1;117(2):456–487. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda SK, Daemen M, Sahoo G, Luyten W. Essential Oils as Novel Anthelmintic Drug Candidates. Molecules. 2022 Nov 29;27(23) doi: 10.3390/molecules27238327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosoff ML, Bürglin TR, Li C. Alternatively spliced transcripts of the flp-1 gene encode distinct FMRFamide-like peptides in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1992 Jun 1;12(6):2356–2361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02356.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby HA. Anthelmintics Resistance; How to Overcome it? Iran J Parasitol. 2013 Jan 1;8(1):18–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora RA, Helder J, Molendijk LPG, Desaeger J, Eves-van den Akker S, Mahlein AK. Integrated Nematode Management in a World in Transition: Constraints, Policy, Processes, and Technologies for the Future. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2023 May 15;61:209–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-021622-113058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starich TA, Herman RK, Kari CK, Yeh WH, Schackwitz WS, Schuyler MW, Collet J, Thomas JH, Riddle DL. Mutations affecting the chemosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995 Jan 1;139(1):171–188. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strydom T, Lavan RP, Torres S, Heaney K. The Economic Impact of Parasitism from Nematodes, Trematodes and Ticks on Beef Cattle Production. Animals (Basel) 2023 May 10;13(10) doi: 10.3390/ani13101599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SR, Santpere G, Weinreb A, Barrett A, Reilly MB, Xu C, Varol E, Oikonomou P, Glenwinkel L, McWhirter R, Poff A, Basavaraju M, Rafi I, Yemini E, Cook SJ, Abrams A, Vidal B, Cros C, Tavazoie S, Sestan N, Hammarlund M, Hobert O, Miller DM 3rd. Molecular topography of an entire nervous system. Cell. 2021 Jul 7;184(16):4329–4347.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner LE, Zhou GT, Schafer RW, Schafer WR. Control of alternative behavioral states by serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron. 1998 Jul 1;21(1):203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JC, Robinson KJ, Lockery SR, Roberts WM. Anthelmintic drug actions in resistant and susceptible C. elegans revealed by electrophysiological recordings in a multichannel microfluidic device. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2018 Oct 30;8(3):607–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JH, Carlson SA, Jones DE, Brewer MT. Molecular mechanisms for anthelmintic resistance in strongyle nematode parasites of veterinary importance. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jun 15;40(2):105–115. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986 Nov 12;314(1165):1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO | Soil-transmitted helminth infections. In: WHO [Internet]. [cited 25 Feb 2017]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs366/en/