Abstract

This study examines the association between the Canadian wildfires that occurred in summer 2023 with emergency department visits for asthma symptoms in New York City.

The wildfires in Canada in 20231 deteriorated air quality locally and distantly. For example, the smoke of wildfires in Quebec drifted into New York City (NYC), hundreds of kilometers away, and caused increased ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on June 6 to 8, 2023. Wildfire PM2.5 has been shown to affect respiratory health, cardiovascular health, birth outcomes, and mental health.2 However, previous work has mostly focused on populations residing near and affected directly by wildfires.3,4 We examined the association between the 2023 Canadian wildfires and asthma syndrome emergency department (ED) visits in NYC.

Methods

Deidentified asthma syndrome ED visits were obtained from the NYC syndromic surveillance system,5 which records information on patients’ visits, age, and residential zip code each day from all 53 EDs in the city. Asthma syndrome includes ED chief complaint mention of asthma, wheezing, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and was identified by a text-processing algorithm.5 Ambient PM2.5 concentrations from 10 local monitoring stations were obtained from the US Environmental Protection Agency. This study used public surveillance data and was exempt from further ethical review by the Yale University institutional review board.

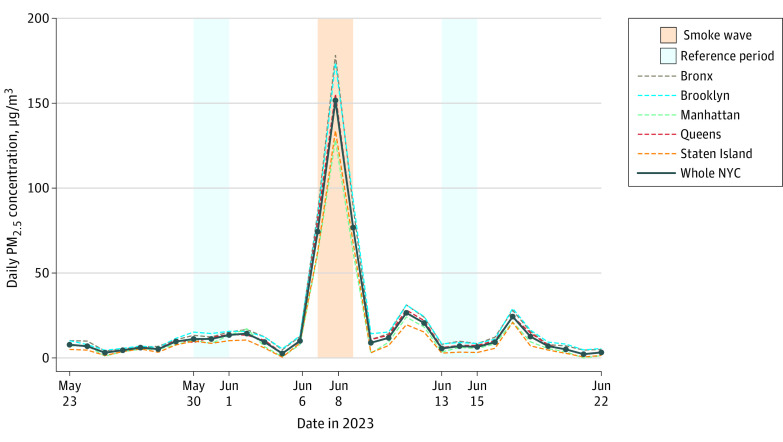

We defined the wildfire smoke wave as at least 2 consecutive days with daily mean PM2.5 exceeding the maximum level (56.8 μg/m3) during a baseline period of January 2021 to May 2023, which was June 6 to 8, 2023. To control for the day-of-the-week effect, we used 2 adjacent, nonsmoke periods with the same days of the week as the smoke wave as the reference period: May 30 to June 1 and June 13 to 15. To estimate the association between the smoke wave and asthma syndrome ED visits, we calculated the incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CIs of visits between the smoke wave and reference period. We also conducted subgroup analyses by age groups and boroughs and sensitivity analyses using alternative reference periods (May 30-June 1 and June 13-15 separately, or May 23-25 and June 20-22) and excluding visits with missing zip code (3.8% [30/783] and 5.1% [55/1089] during smoke wave and reference period). The short study period helped mitigate potential population-level confounding. Analyses were conducted using the fmsb package in R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and statistical significance was defined as a 95% CI not crossing 1.

Results

During the smoke wave, citywide daily mean PM2.5 levels reached 100.9 μg/m3 (reference, 9.0 μg/m3) and asthma syndrome ED visits increased to 261 per day (reference, 181.5 per day), both peaking on June 7, 2023 (Figure and Table). In contrast, daily mean temperature was generally similar during the smoke wave and the reference period (22.6 vs 24.8 °C).

Figure. Daily Fine Particulate Matter Concentration Before, During, and After the 2023 June Wildfire Smoke Wave in New York City.

NYC indicates New York City; PM2.5, fine particulate matter.

Table. Asthma Syndrome ED Visits by Age Groups and Boroughs in New York City Before, During, and After the Wildfire Smoke Wave in June 2023a.

| Population | No. of ED visits | IRR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before smoke wave (May 30-June 1) | Smoke wave (June 6-8) | After smoke wave (June 13-15) | |||

| New York City | |||||

| All age groups | 8 335 897 | 523 | 783 | 566 | 1.44 (1.31-1.58) |

| Age 0-4 y | 516 826 | 19 | 28 | 31 | 1.12 (0.71-1.78) |

| Age 5-17 y | 1 225 377 | 87 | 112 | 83 | 1.32 (1.04-1.67) |

| Age 18-64 y | 5 334 974 | 344 | 562 | 394 | 1.52 (1.36-1.70) |

| Age ≥65 y | 1 258 720 | 73 | 81 | 58 | 1.24 (0.94-1.63) |

| Borough | |||||

| Bronx | 1 379 946 | 146 | 215 | 156 | 1.42 (1.20-1.70) |

| Brooklyn | 2 590 516 | 173 | 247 | 192 | 1.35 (1.15-1.59) |

| Manhattan | 1 596 273 | 97 | 138 | 93 | 1.45 (1.17-1.81) |

| Queens | 2 278 029 | 69 | 128 | 89 | 1.62 (1.28-2.05) |

| Staten Island | 491 133 | 13 | 25 | 6 | 2.63 (1.45-4.78) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

The New York City (New York, New York) population in total and for each age group and each borough is assumed to have remained the same before, during, and after the smoke wave in June 2023. Borough-specific IRRs were not adjusted for age.

We estimated significant increases in asthma syndrome ED visits during the smoke wave compared with nonsmoke periods in NYC overall (IRR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.31-1.58) and all of its 5 boroughs (Table). We also estimated significant increases in visits among groups aged 5 to 17 years (IRR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.04-1.67) and 18 to 64 years (IRR = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.36-1.70). Similar IRRs were estimated using the alternative reference periods (May 30-June 1, 1.50 [95% CI, 1.34-1.67]; June 13-15, 1.38 [95% CI, 1.24-1.54]; and May 23-25 and June 20-22, 1.52 [95% CI, 1.39, 1.67]) or excluding visits with missing zip code (1.46; 95% CI, 1.33-1.60).

Discussion

Despite being located hundreds of kilometers away, the Canadian wildfires were associated with increased asthma syndrome ED visits in NYC during the June 2023 smoke wave. This association was acute (highest in the second day of the smoke wave) and affected individuals aged 5 to 64 years and all boroughs. Study limitations include the ecologic study design, study area restricted to NYC, examination of only one acute outcome based on syndromic surveillance, and lack of accounting for changes in population activity patterns or movement. Given the findings and that wildfires have become more frequent and larger in recent years as a result of a warming climate, timely communication about limiting wildfire smoke exposure is needed to protect vulnerable populations.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Karen Lasser, MD, and Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editors.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Natural Resources Canada . National wildland fire situation report. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/report

- 2.Reid CE, Brauer M, Johnston FH, Jerrett M, Balmes JR, Elliott CT. Critical review of health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(9):1334-1343. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu JC, Wilson A, Mickley LJ, et al. Wildfire-specific fine particulate matter and risk of hospital admissions in urban and rural counties. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):77-85. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doubleday A, Sheppard L, Austin E, Busch Isaksen T. Wildfire smoke exposure and emergency department visits in Washington State. Environ Res Health. 2023;1(2):025006. doi: 10.1088/2752-5309/acd3a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lall R, Abdelnabi J, Ngai S, et al. Advancing the use of emergency department syndromic surveillance data, New York City, 2012-2016. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(1 suppl):23S-30S. doi: 10.1177/0033354917711183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement