This randomized clinical trial evaluates whether a biomarker-driven, risk-directed approach to thromboprophylaxis would prevent thromboembolism among adults with lung and gastrointestinal (GI) cancers receiving anticancer therapies in ambulatory treatment settings.

Key Points

Question

Can a biomarker-driven, risk-directed approach to thromboprophylaxis prevent thromboembolism among individuals with lung and gastrointestinal cancers receiving anticancer therapies in ambulatory treatment settings?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 328 adults, thromboembolism and death were significantly reduced among individuals with high-risk biomarker profiles receiving enoxaparin vs those not receiving thromboprophylaxis. Risk-directed thromboprophylaxis mitigated thrombosis rates among individuals with high-risk profiles to those comparable to rates among individuals with low-risk profiles, without safety concerns.

Meaning

The findings support a biomarker-driven, risk-directed primary thromboprophylaxis approach in adults with lung and gastrointestinal cancers with high-risk profiles as routine care for maximal clinical benefit.

Abstract

Importance

Thromboprophylaxis for individuals receiving systemic anticancer therapies has proven to be effective. Potential to maximize benefits relies on improved risk-directed strategies, but existing risk models underperform in cohorts with lung and gastrointestinal cancers.

Objective

To assess clinical benefits and safety of biomarker-driven thromboprophylaxis and to externally validate a biomarker thrombosis risk assessment model for individuals with lung and gastrointestinal cancers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This open-label, phase 3 randomized clinical trial (Targeted Thromboprophylaxis in Ambulatory Patients Receiving Anticancer Therapies [TARGET-TP]) conducted from June 2018 to July 2021 (with 6-month primary follow-up) included adults aged 18 years or older commencing systemic anticancer therapies for lung or gastrointestinal cancers at 1 metropolitan and 4 regional hospitals in Australia. Thromboembolism risk assessment based on fibrinogen and d-dimer levels stratified individuals into low-risk (observation) and high-risk (randomized) cohorts.

Interventions

High-risk patients were randomized 1:1 to receive enoxaparin, 40 mg, subcutaneously daily for 90 days (extending up to 180 days according to ongoing risk) or no thromboprophylaxis (control).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was objectively confirmed thromboembolism at 180 days. Key secondary outcomes included bleeding, survival, and risk model validation.

Results

Of 782 eligible adults, 328 (42%) were enrolled in the trial (median age, 65 years [range, 30-88 years]; 176 male [54%]). Of these participants, 201 (61%) had gastrointestinal cancer, 127 (39%) had lung cancer, and 132 (40%) had metastatic disease; 200 (61%) were high risk (100 in each group), and 128 (39%) were low risk. In the high-risk cohort, thromboembolism occurred in 8 individuals randomized to enoxaparin (8%) and 23 control individuals (23%) (hazard ratio [HR], 0.31; 95% CI, 0.15-0.70; P = .005; number needed to treat, 6.7). Thromboembolism occurred in 10 low-risk individuals (8%) (high-risk control vs low risk: HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.58-6.99; P = .002). Risk model sensitivity was 70%, and specificity was 61%. The rate of major bleeding was low, occurring in 1 participant randomized to enoxaparin (1%), 2 in the high-risk control group (2%), and 3 in the low-risk group (2%) (P = .88). Six-month mortality was 13% in the enoxaparin group vs 26% in the high-risk control group (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24-0.93; P = .03) and 7% in the low-risk group (vs high-risk control: HR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.13-10.42; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial of individuals with lung and gastrointestinal cancers who were stratified by risk score according to thrombosis risk, risk-directed thromboprophylaxis reduced thromboembolism with a desirable number needed to treat, without safety concerns, and with reduced mortality. Individuals at low risk avoided unnecessary intervention. The findings suggest that biomarker-driven, risk-directed primary thromboprophylaxis is an appropriate approach in this population.

Trial Registration

ANZCTR Identifier: ACTRN12618000811202

Introduction

Cancer-associated thromboembolism contributes to substantial adverse health burden for individuals and the health care system.1,2 Despite many prior trials,3,4,5,6,7 evidence-based guidelines,8,9 and extensive clinical experience using antithrombotic agents for primary prophylaxis, clinical application remains a significant challenge among individuals receiving systemic anticancer therapies in ambulatory settings. This is largely due to the heterogeneity and dynamic nature of risk profiles among individuals as well as concerns for bleeding.10

Benefits and feasibility of risk stratification and risk-directed (targeted) thromboprophylaxis have been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials.6,7 However, findings may not be applicable to all tumor groups given use of a risk assessment model (RAM) heavily weighted for tumor type11 and thus with limited stratification within tumor types10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 as well as residual risk masked by exclusion of individuals designated as low risk. Alternate RAMs are available19,20,21,22 but remain limited by low sensitivity or specificity, nonroutine tests, and/or lack of ability to stratify risk within tumor groups. This trial aimed to bridge this gap by evaluating the efficacy and safety of thromboprophylaxis targeted to individuals designated as high risk by a simple biomarker-based RAM (d-dimer and fibrinogen levels before and during treatment), with inclusion of a low-risk cohort to address residual risk and RAM performance.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

Targeted Thromboprophylaxis in Ambulatory Patients Receiving Anticancer Therapies (TARGET-TP) was an open-label, phase 3 randomized clinical trial that included an observational arm (low thromboembolic risk) and randomized arms (high thromboembolic risk). The trial was conducted from June 2018 to July 2021, with 6-month primary follow-up. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are given in Supplement 1, and trial schema are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. Data are reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. Trial design, protocol development, and implementation were overseen by the trial steering committee, and review of trial conduct and safety data was assessed by a data safety monitoring board. The trial was conducted using the networked teletrial methods23 (eMethods in Supplement 2). The trial protocol was ethically approved by the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Human Research Ethics Committee and prospectively registered (ACTRN12618000811202). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Individuals aged 18 years or older with clinician-estimated life expectancy of at least 6 months were enrolled prior to commencement of systemic anticancer therapies with or without radiotherapy for gastrointestinal or lung cancer (newly diagnosed or relapsed or progressive disease, curative or palliative intent) at 5 hospitals in Australia (1 metropolitan, 4 regional). Those with contraindication to enoxaparin, including conditions placing them at high risk of bleeding or requiring therapeutic anticoagulation, were ineligible. Full criteria are given in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Thromboembolism Risk Assessment

Thromboembolic risk was classified according to a RAM incorporating fibrinogen and d-dimer levels that was previously developed in a cohort with lung cancer and validated in a small, prospective cohort with gastrointestinal cancer.10 Fibrinogen and d-dimer levels, assessed by standard assay at 4 local diagnostic pathology laboratories, were measured prior to initiating cancer treatment (to assess individual and tumor-driven thromboembolic risk profiles) and again after 1 cycle of treatment (month 1; to assess treatment and tumor breakdown thromboembolic risk profiles). Three d-dimer assays (INNOVANCE D-Dimer Assay [Innovance], DDHS500 [HemosIL], and STA-Liatest D-Di [Stago]) approved by the Australian National Association of Testing Authorities were used. High-risk status was assigned for individuals with (1) pretreatment fibrinogen level of 400 mg/dL or more (to convert to g/L, multiply by 0.01) and d-dimer level of 0.5 μg/mL or more (to convert to nmol/L, multiply by 5.476), (2) pretreatment d-dimer level of 1.5 μg/mL or more, or (3) month 1 d-dimer level of 1.5 μg/mL or more.10 In all cohorts, time at risk commenced at baseline risk assessment.

Randomization and Interventions

Individuals classified at high risk (baseline or month 1) were randomized 1:1 to enoxaparin, 40 mg, subcutaneously daily for a minimum of 90 days (extended up to 180 days according to ongoing risk) or no thromboprophylaxis (control) (eMethods in Supplement 2). Participants were randomized in blocks according to site of enrollment, treatment intent (curative or palliative), and cancer diagnosis. For individuals classified at low risk, anticancer treatment continued without randomization and thromboprophylaxis (observational cohort). For primary outcome measures, participants were followed up to 180 days (±30 days) regardless of cohort assignment or duration of enoxaparin therapy.

End Points and Assessments

The primary outcome was objectively confirmed symptomatic or incidental thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis [DVT], pulmonary embolism [PE], and arterial thromboembolism) within 180 days after randomization (full definitions are given in the eMethods in Supplement 2). Events were confirmed by clinically indicated routine diagnostic imaging, with no routine surveillance for incidental events. Events were diagnosed as part of standard clinical care and reviewed by an independent data safety monitoring committee. Post hoc analysis of the primary outcome was conducted for the intervention period (duration of enoxaparin therapy) to align with CASSINI trial reporting.6

Secondary outcomes included major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor (CRNM) bleeding related to enoxaparin. Major and CRNM bleeding were defined according to standard criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (eMethods in Supplement 2).24 Severity was assigned according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.25 Enoxaparin treatment adherence was estimated by device count of returned product and by self-report at routine visits.

A secondary objective was to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the thromboembolism RAM based on observed thromboembolism events among individuals not receiving enoxaparin (high-risk control arm vs low-risk observational arm). Other secondary objectives, ongoing and/or not reported here, include response to cancer therapies, 2-year progression-free survival, 2-year overall survival, patient-reported outcomes (quality of life, clot awareness, and anticlot treatment evaluation), and health care resource utilization associated with thromboprophylaxis and thromboembolism. Race was reported by participants according to investigator-defined options given evidence of disparate thrombosis risk. Categories were Asian, White, and other (not reported because unspecified in electronic case report form).

Statistical Analysis

A target of 200 high-risk individuals (100 per randomized arm) provided more than 80% power to detect a 4-fold reduction in thromboembolic risk (2-sided α = 5%; 5% vs 20%), allowing for 10% dropout. Expected rates were based on the BIOTEL trial, in which the RAM was developed.10 The primary end point was cumulative incidence of objectively confirmed venous or arterial thromboembolism at 180 days (30-day window) in randomized arms, analyzed by cause-specific Cox proportional hazards regression with intention to treat. Exploratory analyses were predefined for the assessment of cumulative incidence of thromboembolism and bleeding according to cancer type, stage, anticancer therapy, and trial recruitment site by inclusion of these factors in multivariable cause-specific Cox proportional hazards regression models. The cumulative incidence functions for thromboembolism were used to estimate thromboembolism incidence at 180 days after baseline risk assessment, noting that the cumulative incidence function depends on the cause-specific hazards of both thromboembolism and the competing event of death. As for thromboembolism, bleeding risk was assessed using univariable case-specific Cox proportional hazards regression models with separate analyses for major, CRNM, and major or CRNM bleeding. Adverse events other than bleeding that were probably or definitely related to the study drug were categorized and graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.25

Among individuals not receiving thromboprophylaxis, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and C statistic for performance of the RAM were assessed by cause-specific analyses using standard methods further described in the eMethods in Supplement 2. Best overall response was reported based on standard-of-care imaging by the treating clinician guided by RECIST, version 1.1 definitions.26 Follow-up time was estimated by the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Progression-free survival and overall survival were assessed in interim analyses by Kaplan-Meier methods, with a closeout date of last follow-up for the primary end point. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA/IC, version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC) with a significance level of 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Participants

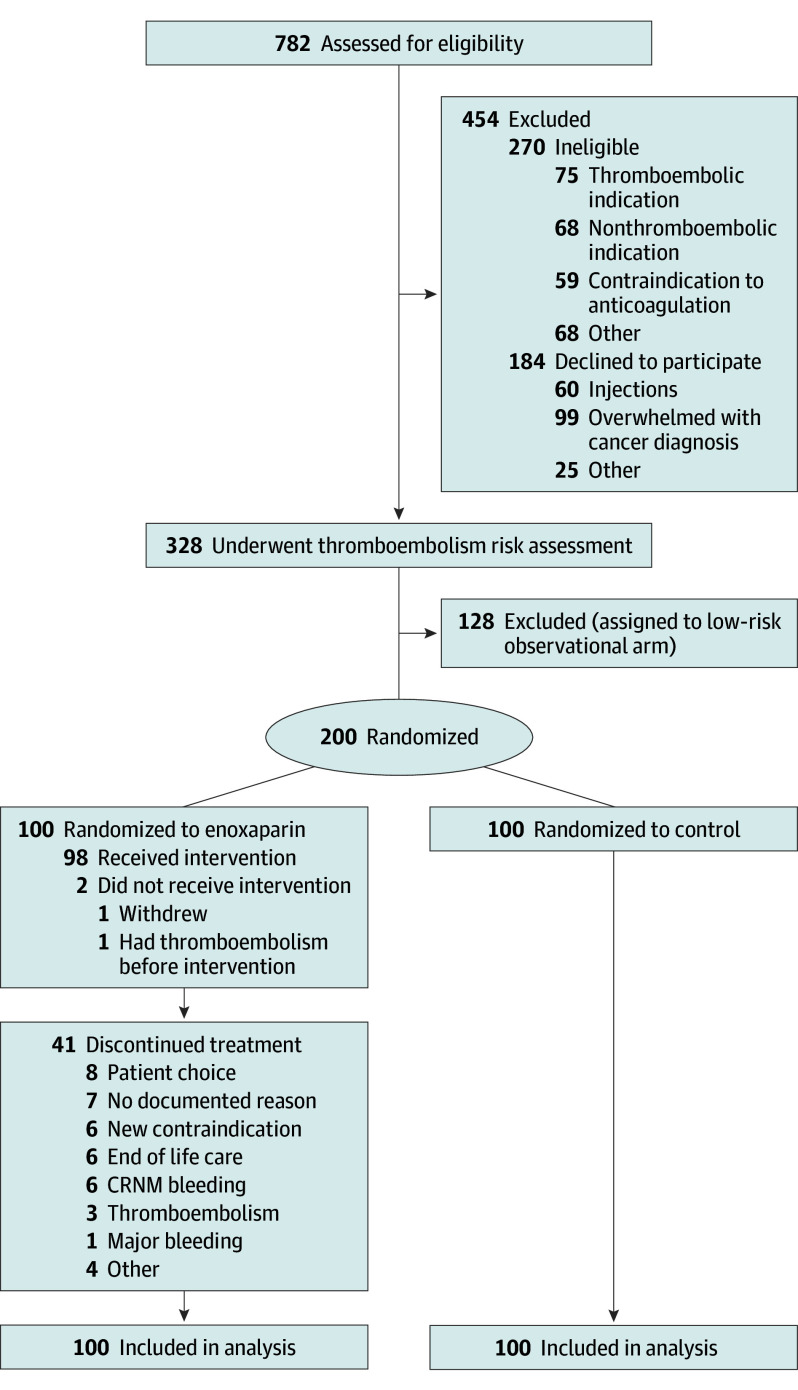

Of 782 eligible participants who were screened, the study cohort included 328 (median age, 65 years [range, 30-88 years]; 152 [46%] female; 176 [54%] male) enrolled across 5 Australian hospitals between June 2018 and July 2021: 176 at the metropolitan primary site (54%) and 152 at 4 regional networked satellite sites (46%). Of the total participants, 18 (6%) were Asian; 303 (92%), White; and 7 (2%), other race. A total of 201 participants (61%) had gastrointestinal cancer, 127 (39%) had lung cancer, and 132 (40%) had metastatic disease. Among the participants, 200 classified as high risk (61%) underwent randomization, and 128 individuals with low risk (39%) were enrolled in the observational arm. All individuals randomized were included in the intention-to-treat primary end point analysis cohort (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Of the 270 participants who were ineligible, 5 were excluded after signing consent (before randomization) due to demonstrable indications for therapeutic anticoagulation, including detected thromboembolism (n = 3) or known cardiac conditions (n = 2). Of the 128 participants in the low-risk observational arm, 35 had lung cancer and 93 had gastrointestinal cancer. Of the 200 participants in the high-risk arm, 92 had lung cancer and 108 had gastrointestinal cancer. Of the 100 participants assigned to receive enoxaparin and the 100 in the control group, each arm included 46 participants with lung cancer and 54 with gastrointestinal cancer. CRNM indicates clinically relevant nonmajor.

Participant characteristics were balanced across the randomized arms. Low-risk individuals were more likely to have gastrointestinal cancer diagnoses and nonmetastatic disease (Table). Most participants (306 [93%]) were treated with chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy or immunotherapy). Stage, predominant sites of disease, and other key demographics are given in the Table.

Table. Characteristics of Enrolled Participantsa.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 328) | Low risk (n = 128) | High-risk enoxaparin (n = 100) | High-risk control (n = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 65 (30-88) | 64 (33-88) | 67 (30-87) | 66 (31-85) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 152 (46) | 69 (54) | 38 (38) | 45 (45) |

| Male | 176 (54) | 59 (46) | 62 (62) | 55 (55) |

| Weight, median (range), kg | 74 (42-130) | 73 (42-130) | 75 (52-109) | 73 (46-116) |

| Creatinine clearance, <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 18 (6) | 9 (7) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) |

| White | 303 (92) | 118 (92) | 93 (93) | 92 (92) |

| Otherb | 7 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Thoracic | 127 (39) | 35 (27) | 46 (46) | 46 (46) |

| NSCLC nonsquamous | 79 (24) | 23 (18) | 26 (26) | 30 (30) |

| NSCLC squamous | 27 (8) | 6 (5) | 13 (13) | 8 (8) |

| SCLC | 15 (5) | 6 (5) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Pleural mesothelioma | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 201 (61) | 93 (73) | 54 (54) | 54 (54) |

| Colon | 67 (20) | 31 (24) | 15 (15) | 21 (21) |

| Rectum | 32 (10) | 17 (13) | 5 (5) | 10 (10) |

| Pancreas | 36 (11) | 19 (15) | 9 (9) | 8 (8) |

| Esophagus | 31 (9) | 10 (8) | 14 (14) | 7 (7) |

| Stomach | 11 (3) | 4 (3) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Appendix | 8 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Anus | 8 (2) | 8 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| Otherc | 8 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 312 (96) | 124 (97) | 96 (96) | 92 (92) |

| ≥2 | 12 (4) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) |

| Unknown | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Treatment site | ||||

| Metropolitan | 176 (54) | 62 (48) | 58 (58) | 56 (56) |

| Regional | 152 (46) | 66 (52) | 42 (42) | 44 (44) |

| Diagnosis presentation | ||||

| New diagnosis | 253 (77) | 99 (77) | 76 (76) | 84 (84) |

| Recurrent disease | 75 (23) | 29 (23) | 24 (24) | 16 (16) |

| Metastatic disease | 132 (40) | 36 (28) | 52 (52) | 44 (44) |

| Anticancer treatment at enrollment | ||||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 72 (22) | 34 (27) | 18 (18) | 20 (20) |

| Chemotherapy | 210 (64) | 83 (65) | 63 (63) | 64 (64) |

| Chemotherapy and immunotherapy | 24 (7) | 8 (63) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) |

| Immunotherapy | 21 (6) | 3 (2) | 11 (11) | 7 (7) |

| Targeted therapy | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Prior thromboembolism | 14 (4) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 7 (7) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

SI conversion: To convert creatinine clearance to milliliters per second per square meter, multiply by 0.0167.

Data are reported as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Other race was not reported because unspecified in electronic case report form.

Included cancer of the small intestine (n = 5), liver (n = 2), and gallbladder (n = 1).

Enoxaparin Thromboprophylaxis

Among individuals randomized to enoxaparin, 98 of 100 (98%) received enoxaparin; of the 2 who did not receive treatment, 1 developed PE before initiating anticancer therapy and study drug and 1 withdrew consent before initiating study drug. Median duration of enoxaparin therapy was 90 days (range, 3-210 days), with 74 of 98 participants (75%) receiving enoxaparin for 70 days or more and 57 of 98 (58%) for 90 days or more. Reasons for cessation prior to 90 days are given in Figure 1.

Thromboembolism

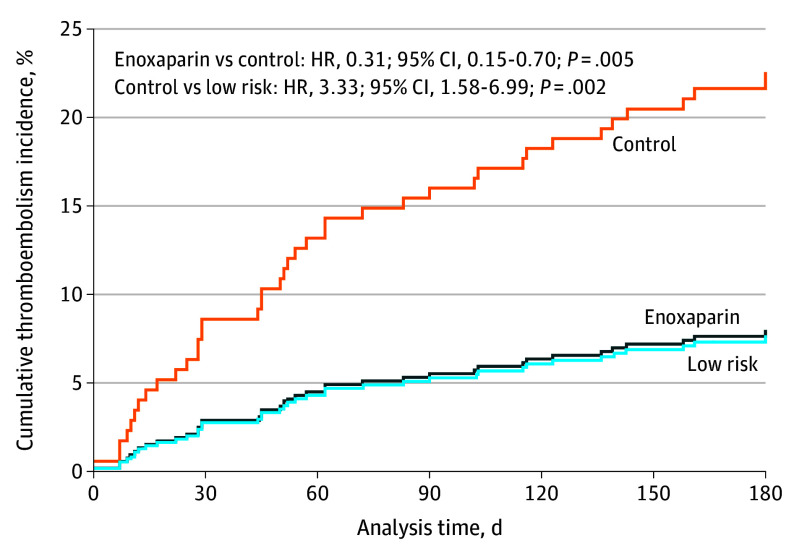

Of the 44 thromboembolic events, 41 (93%) were reported in the 6-month primary analysis period: DVT (21 events, including 4 upper-extremity catheter-related events), PE (14 events), DVT and PE (3 events), and myocardial infarction (3 events). Three individuals experienced recurrent events during follow-up: DVT followed by catheter-related thrombosis (n = 1) and DVT followed by PE (n = 2). Myocardial infarction occurred in 2 individuals during hospitalization for sepsis and 1 older individual in the context of underlying cardiac disease. Median time to thromboembolism was 52 days (range, 1-190 days). Median follow-up in the group randomized to enoxaparin was 180 days (range, 6-262 days), to control was 180 days (range, 0.5-231 days), and in the low-risk group was 183 days (range, 10-245 days). Cumulative incidence of thromboembolism to 180 days is presented by cohort in Figure 2. Events by race are described in the eResults in Supplement 2.

Figure 2. Cumulative Thromboembolism Incidence Within 180 Days According to Thromboembolism Risk Classification and Randomization.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

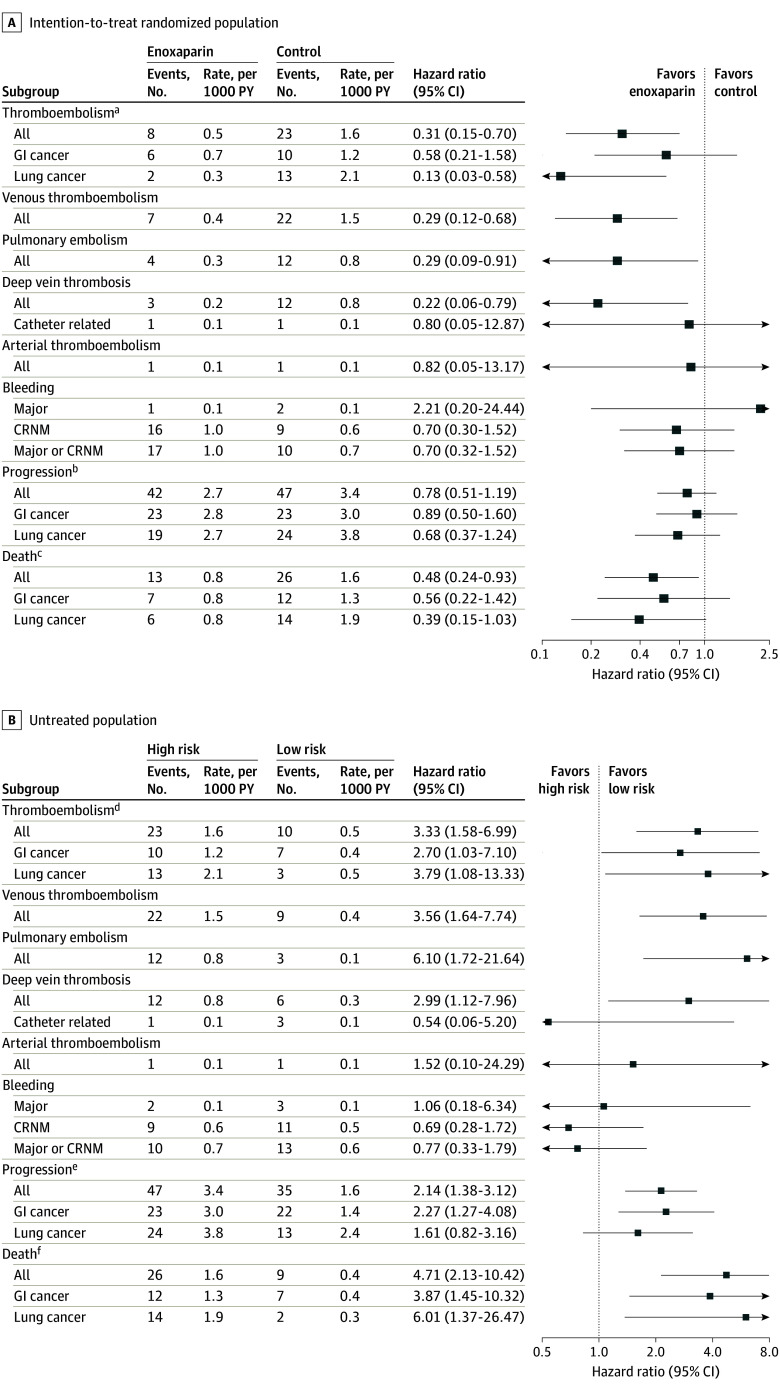

Thromboembolism occurred in 8 of 100 individuals randomized to enoxaparin (8%) and in 23 of 100 randomized to control (23%) (hazard ratio [HR], 0.31; 95% CI, 0.15-0.70; P = .005) (Figure 3A). This represents an absolute risk reduction of 15% and relative risk reduction of 65%. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent a thromboembolic episode was 6.7. Thromboembolism occurred in 10 of 128 low-risk individuals (8%) (high-risk control vs low risk: HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.58-6.99; P = .002) (Figure 3B). Venous thromboembolism (excluding arterial events) occurred in 7 of 100 in the enoxaparin group (7%), 22 of 100 in the control group (22%), and 9 of 128 in the low-risk group (7%). Analyses by cohort and for predefined subgroups of interest with univariable and multivariable analyses are given in eTable 1 and eFigures 2 and 3 in Supplement 2.

Figure 3. Thromboembolism, Bleeding, Cancer Progression, and All-Cause Mortality Within 180 Days in the Intention-to-Treat Randomized Population and Low-Risk Population According to Subgroup.

The intention-to-treat population included all eligible participants classified as being at high risk of thromboembolism who underwent randomization and eligible participants classified as low risk. Markers indicate hazard ratios, and horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. CRNM indicates clinically relevant nonmajor; GI, gastrointestinal; PY, person-years.

aP = .10 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

bP = .65 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

cP = .52 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

dP = .63 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

eP = .29 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

fP = .93 for interaction (GI vs lung cancer).

Among those randomized to enoxaparin, 6 of 8 thromboembolic events (75%) occurred without active enoxaparin therapy. In a post hoc intervention period analysis, thromboembolism occurred in just 2 of 98 individuals randomized to enoxaparin (2%) and 23 of 100 in the control group (23%) (HR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02-0.44; P = .002; NNT, 4.8). All 6 individuals who developed thromboembolism in the absence of active enoxaparin therapy had gastrointestinal cancer: 2 events occurred shortly after completing protocol-planned prophylaxis, 2 individuals ceased therapy due to bleeding events, 1 individual ceased therapy for end-of-life care, and 1 event occurred shortly after randomization prior to initiation of anticancer and enoxaparin therapy (median time to event, 128 days [range, 7-158 days]). Among 2 individuals with lung cancer (1 with metastatic disease undergoing systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy and 1 with locally advanced disease undergoing curative chemoradiotherapy), events occurred during enoxaparin treatment (time to event, 70 days [range, 57-83 days]). The thromboembolism rate in the TARGET-TP lung cancer control population with lung cancer was 28% (13 of 46) and with gastrointestinal cancer was 19% (10 of 54). In the low-risk cohort, 3 events were catheter-related, 1 arterial, and 6 lower-limb DVT or PE (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Among the low-risk cohort, the rate of thromboembolism, excluding catheter-related and arterial events, was 5% (with a net 0 target).

There was no statistical evidence of differing treatment effect with the applied risk-directed strategy between lung and gastrointestinal subtypes (eResults in Supplement 2). Thromboembolism rates, according to the Khorana RAM, of individuals in the nonintervention arms were 17% (13 of 76) for high risk and 13% (20 of 152) for low risk, with no difference between the groups (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.74-3.02).

Bleeding and Other Adverse Events

Bleeding occurred in 40 of all 328 individuals (12%), including 6 (2%) with major bleeding (1 of 100 in the enoxaparin group [1%], 2 of 100 in the high-risk control group [2%], and 3 of 128 in the low-risk group [2%]; P = .88) and 36 (11%) with CRNM bleeding (2 had both major and CRNM events). Major and CRNM bleeding were not statistically different across the groups (major bleeding enoxaparin vs control: HR, 2.21; 95% CI, 0.20-24.44) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Nonbleeding events occurred in 13 of 100 individuals (13%) in the enoxaparin arm and included bruising (n = 12), hematoma (n = 2), and thrombocytopenia (n = 1) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Risk Classification and Risk Model Performance

High-risk classification for 200 individuals occurred at baseline (183 [91%]) and month 1 (17 [9%]), with 2 of 17 (12%) classified at month 1 subsequently developing thromboembolism. Among 228 individuals who did not receive thromboprophylaxis (high-risk control [n = 100] and low-risk observational [n = 128]), thromboembolism incidence was 23% (23 in high-risk control group) and 8% (10 in low-risk group) (HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.58-6.99). Risk assessment model sensitivity was 70%; specificity, 61%; positive predictive value, 23%; negative predictive value, 92%; and C statistic, 0.64. A greater proportion of high-risk individuals compared with low-risk individuals were male (117 [59%] vs 59 [46%]) and had a diagnosis of lung cancer (92 [46%] vs 35 [27%]) and metastatic disease (96 [48%] vs 36 [28%]). A maximum of 149 TARGET-TP high-risk individuals (75%) were classified as low risk, and 73 low-risk individuals (57%) were classified as high risk by other published RAMs.11,20,21,22 Among 228 individuals who did not receive thromboprophylaxis (high-risk control [n = 100] and low-risk observational [n = 128]), thromboembolism incidence at Khorana risk-score thresholds, as applied in the AVERT7 and CASSINI6 trials, was 17% (13 of 76 with a Khorana score of ≥2) and 13% (20 of 152 with a Khorana score of 0-1) (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.74-3.02).

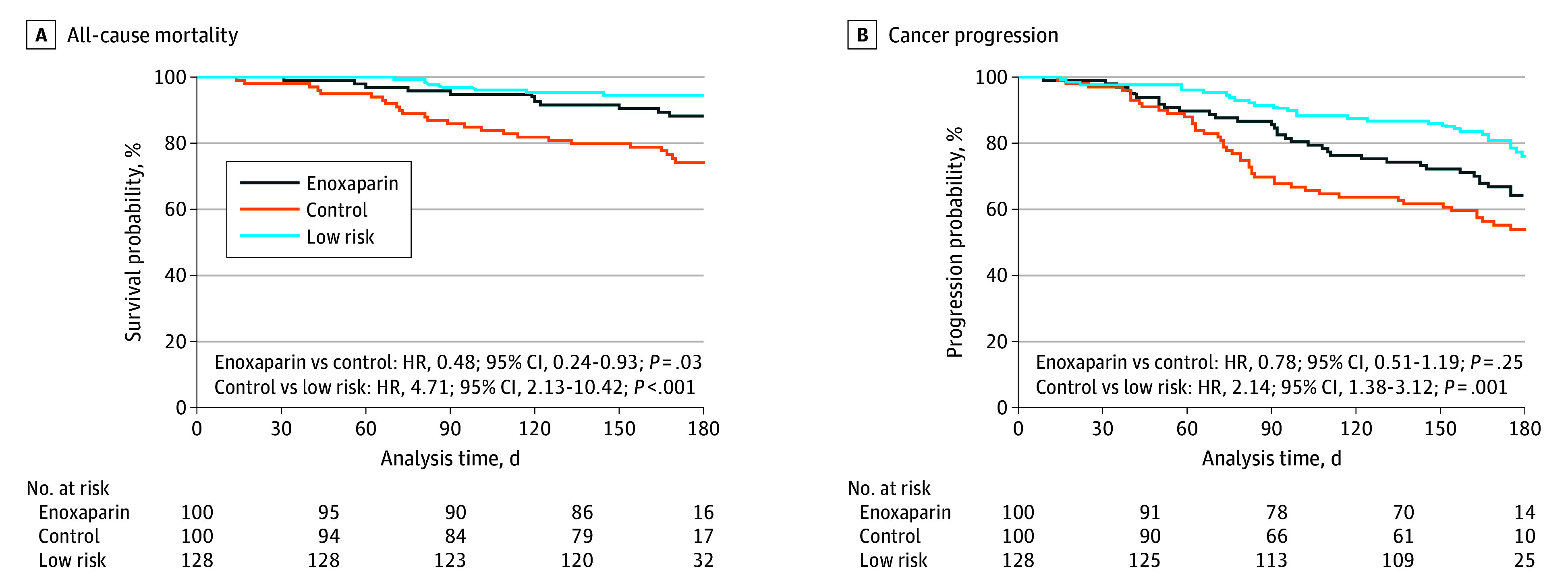

Survival and Response to Anticancer Treatment

For enoxaparin use compared with high-risk control, there was a significant reduction in 6-month all-cause mortality (13% vs 26%; HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24-0.93; P = .03) but not in cancer progression (42% vs 47%; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.51-1.19; P = .25). Among low-risk individuals, 6-month all-cause mortality was 7% (high-risk control vs low risk: HR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.13-10.42; P < .001) and 6-month cancer progression was 27% (high-risk control vs low risk: HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.38-3.12; P = .001). Estimated overall survival and progression-free survival by cohort are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Cumulative Incidence of All-Cause Mortality and Cancer Progression Within 180 Days According to Thromboembolism Risk Classification and Randomization.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

Discussion

The TARGET-TP trial provided external validation of a biomarker-driven approach to thromboembolism risk stratification and demonstrated significant reduction in thromboembolism and mortality with ambulatory thromboprophylaxis targeted to high-risk individuals with lung or gastrointestinal cancer. This trial builds on 2 previous trials of apixaban-targeted (AVERT)7 and rivaroxaban-targeted (CASSINI)6 thromboprophylaxis that reported benefits for a personalized approach to primary clot prevention.

We reported a 15% absolute difference in thromboembolism rates with an NNT of 6.7 (NNT of 4.8 within the intervention period) and 13% absolute difference in mortality rates with an NNT of 8 between randomized cohorts. Comparatively, the NNT for thromboembolism risk reduction was 17 in AVERT (apixaban, Khorana RAM, and mixed cancers),7 36 in CASSINI overall and 26 in the CASSINI intervention period analysis (rivaroxaban, Khorana RAM, and mixed cancers),6 24 in FRAGMATIC (low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH], no RAM, and lung cancer),5 45 in SAVE-ONCO (LMWH, no RAM, and mixed cancers),4 and 54 in PROTECHT (LMWH, no RAM, and mixed cancers).3 Survival benefit was not demonstrated in any of these trials3,4,5,6,7; thus, results of the present study should be cautiously considered to be a chance finding until further validated.

The improved magnitude of thrombosis risk reduction and new finding of mortality risk reduction are likely explained by selection of different treatment groups (better risk stratification) compared with prior trials.3,4,5,6,7 The control group in the present trial had a significantly higher rate of thromboembolism compared with unselected lung or gastrointestinal cancer cohorts or with the Khorana-stratified cohort with lung and gastrointestinal cancers, and we identified significant cohort migration with application of other RAMs to this cohort (full comparisons with other RAMs are forthcoming in future studies). The expected rate of thromboembolism among unselected individuals with lung cancer undergoing anticancer therapies is approximately 15%.10,27 The lower rate of just 5% (5 of 100) in combined AVERT and CASSINI control populations with lung cancer6,28 indicates inappropriateness of the applied RAM for these individuals. The thromboembolism rate in the TARGET-TP control population with lung cancer was 28% (13 of 46). Similarly, combined AVERT and CASSINI control populations with pancreatic and gastric cancer had a thromboembolism rate of 6% (11 of 179) and 10% (11 of 106), respectively,6,7,28,29 compared with 19% (256 of 1336) and 16% (124 of 787) in large, unselected populations with pancreatic and gastric cancer.27 The thromboembolism rate in the TARGET-TP control population with mixed gastrointestinal cancer was 19% (10 of 54; 25% [2 of 8] with pancreatic cancer, 33% [1 of 3] with stomach cancer).

Given established safety and efficacy data, we believe that the choice of an anticoagulant is less important than appropriate cohort selection and acknowledge that we are unlikely to see head-to-head trials of LMWH vs oral agents. TARGET-TP used LMWH as the gold standard at the time of trial commencement prior to availability of safety data of oral anticoagulants,6,7 for which potential drug interactions and bleeding risks have yet to be fully detailed in subgroup analyses. Despite the lack of comprehensive safety data, oral agents have several advantages, particularly related to individuals’ preferences and adherence. Future application of the TARGET-TP RAM should consider use of oral agents or LMWH according to the aforementioned considerations and individual preferences.

In TARGET-TP, biomarker assessments (fibrinogen and d-dimer) were conducted in routine care diagnostic laboratories at participating centers, demonstrating a feasible approach for clinical translation beyond the trial. Importantly, conduct of this trial across 5 sites using 4 pathology services and 3 d-dimer assays approved by the Australian National Association of Testing Authorities gives confidence that specified cutoff values would maintain reliability in clinical practice settings.

By following outcomes in individuals designated to be at low risk for thromboembolism, we were able to validate the RAM and found a risk reduction for high-risk individuals treated with enoxaparin compared with low-risk individuals (8% vs 8%), demonstrative of effective risk mitigation (high-risk group) and appropriate treatment avoidance (low-risk group). While exploratory subgroup analyses appeared to show a more potent effect in patients with lung cancer, we detected no difference of treatment effect by tumor type (interaction model P = .10), and as a next step, we suggest expanded application and evaluation in a broader range of tumor groups.

An 8% thromboembolism rate (5% excluding catheter-related and arterial events) for the low-risk cohort remained higher than the idealistic net 0 target. However, it represents a clinically acceptable risk threshold in the absence of a treat-all approach, which aims to maximize the risk-to-benefit ratio. In the present population, the rate represented a 65% relative risk reduction and was improved compared with the rate from the multiguideline-endorsed Khorana RAM (13% thromboembolism rate among individuals from the high-risk control and low-risk groups of this study with a Khorana score of 0 to 1). The rate was also similar to the 6% to 7% rate reported in cohorts with lung and gastrointestinal cancer classified as low and intermediate risk by the Khorana RAM across multiple studies pooled within 2 meta-analyses.12,13

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths. The lack of a systematic approach and common treat-none approach, which is the current global mainstay of practice, resulted in high rates of potentially preventable thromboembolic events.27 A targeted prevention approach has not yet been adopted despite positive trials,6,7 likely due to limitations. Data from this trial support not only improved risk stratification for a targeted approach but also simple integration to facilitate adoption into routine clinical care. We recognize that the 70% sensitivity and 61% specificity of the RAM ideally should have been higher; however, relative to published RAMs,10,19 it is potent and ready for scaled implementation with a routine test available in diagnostic pathology laboratories.

The TARGET-TP RAM may be preferred compared with other RAMs due to improvements in cohort selection (NNT, 4.8-6.7) and negligible risk of harm (major bleeding: HR, 2.21; 95% CI, 0.20-24.44). The model mitigates the need for an opt-out approach in individuals unlikely to benefit from treatment or with a less favorable risk-to-benefit ratio. Broad eligibility criteria, metropolitan and regional locations, and enrollment of participants with different races support generalizability (eMethods in Supplement 2). This trial was open label in consideration of the substantial participant burden of administering placebo injections.

This study also has limitations. While inferior to a double-blind, placebo-controlled design with objective end points of radiologically confirmed thromboembolism and all-cause mortality, we believe that there was minimal risk of bias for the key primary outcomes. Risk assessment model validation is thus far limited to lung and gastrointestinal cancers.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial found that administration of prophylactic enoxaparin using a biomarker-driven approach significantly reduced incidence of thromboembolism and all-cause mortality within the 180-day trial period. The fibrinogen and d-dimer RAM identified individuals with lung and gastrointestinal cancers who would most benefit from thromboprophylaxis and those who could avoid intervention. Future investigations in expanded tumor groups that incorporate clinician and consumer preference for choice of anticoagulant are warranted.

Trial Protocol and SAP

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Trial Schema

eResults.

eFigure 2. Thromboembolism in the Intention-to-Treat Randomized Population, According to Subgroup

eFigure 3. Thromboembolism in the Intention-to-Treat Untreated Population, According to Subgroup

eTable 1. Efficacy and Safety Outcomes Within 180 Days According to Thromboembolism Risk Classification and Randomization: Univariable and Multivariable Analyses

eTable 2. Nonbleeding Adverse Events Among Patients Randomized to Enoxaparin

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Kourlaba G, Relakis J, Mylonas C, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(1):13-31. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah S, Rubin N, Khorana AA. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients—a comparative analysis between matched patients with cancer with and without a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-99-113581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnelli G, Gussoni G, Bianchini C, Verso M, Tonato M. A Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study on nadroparin for prophylaxis of thromboembolic events in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: the PROTECHT study. Blood. 2008;112(11):6. doi: 10.1182/blood.V112.11.6.6 18574036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agnelli G, George DJ, Kakkar AK, et al. ; SAVE-ONCO Investigators . Semuloparin for thromboprophylaxis in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):601-609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macbeth F, Noble S, Evans J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of standard therapy plus low molecular weight heparin in patients with lung cancer: FRAGMATIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):488-494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khorana AA, Soff GA, Kakkar AK, et al. ; CASSINI Investigators . Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):720-728. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrier M, Abou-Nassar K, Mallick R, et al. ; AVERT Investigators . Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):711-719. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Key NS, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(5):496-520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falanga A, Ay C, Di Nisio M, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: ESMO clinical practice guideline. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(5):452-467. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander M, Ball D, Solomon B, et al. Dynamic thromboembolic risk modelling to target appropriate preventative strategies for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(1):50. doi: 10.3390/cancers11010050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111(10):4902-4907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Es N, Ventresca M, Di Nisio M, et al. ; IPDMA Heparin Use in Cancer Patients Research Group . The Khorana score for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1940-1951. doi: 10.1111/jth.14824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulder FI, Candeloro M, Kamphuisen PW, et al. ; CAT-prediction collaborators . The Khorana score for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica. 2019;104(6):1277-1287. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.209114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansfield AS, Tafur AJ, Wang CE, Kourelis TV, Wysokinska EM, Yang P. Predictors of active cancer thromboembolic outcomes: validation of the Khorana score among patients with lung cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(9):1773-1778. doi: 10.1111/jth.13378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noble S, Alikhan R, Robbins A, Macbeth F, Hood K. Predictors of active cancer thromboembolic outcomes: validation of the Khorana score among patients with lung cancer: comment. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(3):590-591. doi: 10.1111/jth.13594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibata K, Tokushige A, Imamura M, Ikeda Y, Ohishi M. Evaluating the Khorana risk score of gastrointestinal cancer patients during initial chemotherapy as a predictor of patient mortality: a retrospective study. J Cardiol. 2022;79(5):655-663. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barni S, Rosati G, Lonardi S, et al. Khorana score and thromboembolic risk in stage II-III colorectal cancer patients: a post hoc analysis from the adjuvant TOSCA trial. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835919899850. doi: 10.1177/1758835919899850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Es N, Franke VF, Middeldorp S, Wilmink JW, Büller HR. The Khorana score for the prediction of venous thromboembolism in patients with pancreatic cancer. Thromb Res. 2017;150:30-32. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ay C, Dunkler D, Marosi C, et al. Prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Blood. 2010;116(24):5377-5382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelzer U, Sinn M, Stieler J, Riess H. [Primary pharmacological prevention of thromboembolic events in ambulatory patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with chemotherapy?]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138(41):2084-2088. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verso M, Agnelli G, Barni S, Gasparini G, LaBianca R. A modified Khorana risk assessment score for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: the Protecht score. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7(3):291-292. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0784-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pabinger I, van Es N, Heinze G, et al. A clinical prediction model for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a development and validation study in two independent prospective cohorts. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(7):e289-e298. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30063-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins IM, Burbury K, Underhill CR. Teletrials: implementation of a new paradigm for clinical trials. Med J Aust. 2020;213(6):263-265.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. November 27, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2018. https://www.academia.edu/45128044/Common_Terminology_Criteria_for_Adverse_Events_CTCAE_Common_Terminology_Criteria_for_Adverse_Events_CTCAE_v5_0#:~:text=Common%20Terminology%20Criteria%20for%20Adverse%20Events%20%28CTCAE%29%20Version,Grade%20refers%20to%20the%20severity%20of%20the%20AE

- 26.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khorana AA, Dalal M, Lin J, Connolly GC. Incidence and predictors of venous thromboembolism (VTE) among ambulatory high-risk cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in the United States. Cancer. 2013;119(3):648-655. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nayak AL, Zahrai A, Mallick R, et al. Efficacy of primary prevention of venous thromboembolism among subgroups of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a post- hoc analysis of the AVERT trial. Thromb Res. 2021;208:79-82. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vadhan-Raj S, McNamara MG, Venerito M, et al. Rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis in ambulatory patients with pancreatic cancer: results from a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the randomized CASSINI study. Cancer Med. 2020;9(17):6196-6204. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and SAP

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Trial Schema

eResults.

eFigure 2. Thromboembolism in the Intention-to-Treat Randomized Population, According to Subgroup

eFigure 3. Thromboembolism in the Intention-to-Treat Untreated Population, According to Subgroup

eTable 1. Efficacy and Safety Outcomes Within 180 Days According to Thromboembolism Risk Classification and Randomization: Univariable and Multivariable Analyses

eTable 2. Nonbleeding Adverse Events Among Patients Randomized to Enoxaparin

Data Sharing Statement