Abstract

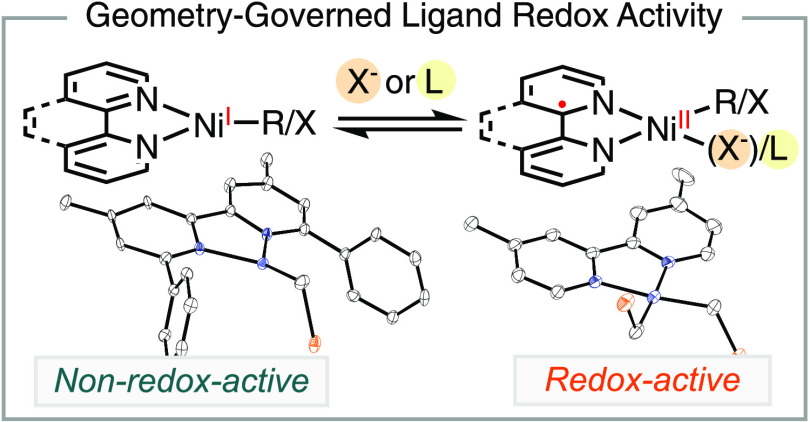

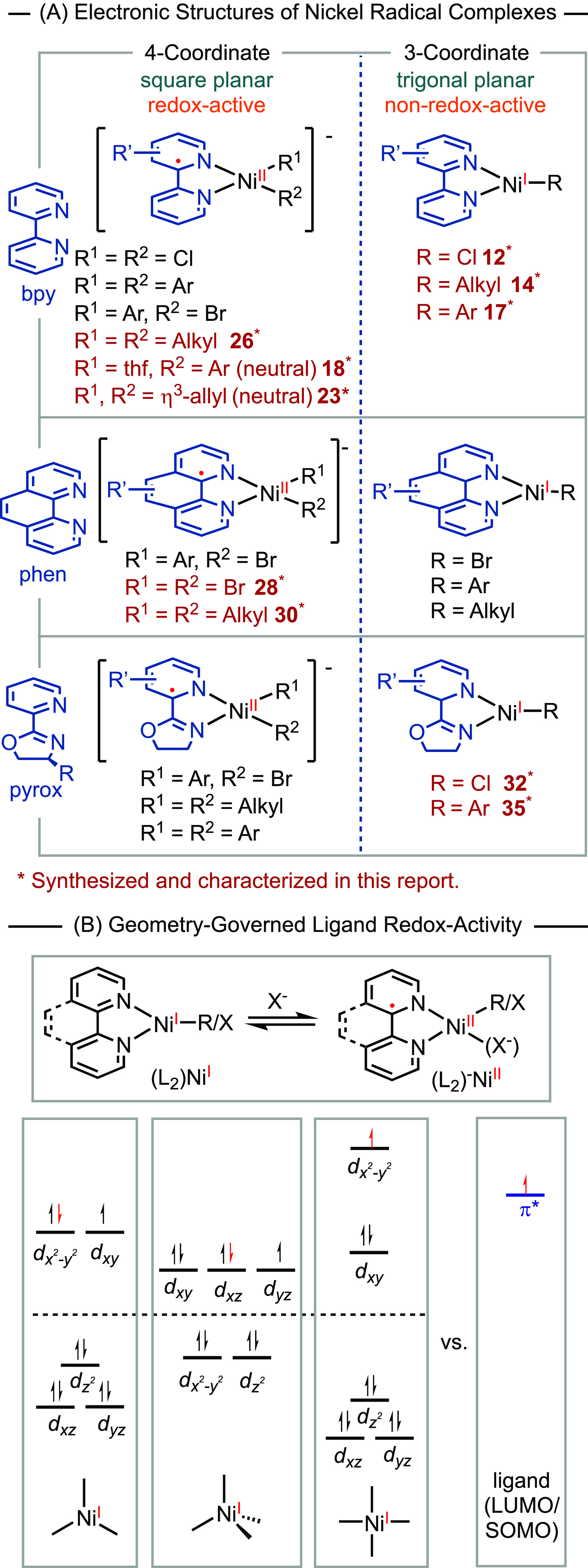

Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions often employ bidentate π-acceptor N-ligands to facilitate radical pathways. This report presents the synthesis and characterization of a series of organonickel radical complexes supported by bidentate N-ligands, including bpy, phen, and pyrox, which are commonly proposed and observed intermediates in catalytic reactions. Through a comparison of relevant analogues, we have established an empirical rule governing the electronic structures of these nickel radical complexes. The N-ligands exhibit redox activity in four-coordinate, square-planar nickel radical complexes, leading to the observation of ligand-centered radicals. In contrast, these ligands do not display redox activity when supporting three-coordinate, trigonal planar nickel radical complexes, which are better described as nickel-centered radicals. This trend holds true irrespective of the nature of the actor ligands. These results provide insights into the beneficial effect of coordinating salt additives and solvents in stabilizing nickel radical intermediates during catalytic reactions by modulating the redox activity of the ligands. Understanding the electronic structures of these active intermediates can contribute to the development and optimization of nickel catalysts for cross-coupling reactions.

Introduction

Recent advancements in the field of cross-coupling reactions have harnessed the reactivity of nickel catalysts to initiate and propagate radical reactions1−6 facilitated by nickel radical intermediates.7−9 Radical pathways involving nickel(I) and (III) intermediates for generating and regulating carbon radicals have paved the way for the application of nickel catalysts in stereo-convergent coupling,10 photoredox, and electrocatalytic reactions,11 significantly broadening the scope and application of cross-coupling reactions. Notably, the cross-electrophile coupling reaction exemplifies the crucial role of distinct nickel(I)-halide12 and nickel(I)-aryl13 species in activating C(sp2) and C(sp3) electrophiles, respectively, through diverse mechanisms (Scheme 1).14,15 Recent research has also revealed the formation of nickel(III) intermediates through the rapid capture of carbon radicals by nickel(II) complexes, with a barrier of 7–9 kcal/mol, enabling efficient reductive elimination.16

Scheme 1. Mechanism of Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions, Key Nickel(I) Radical Intermediates, and Their Stabilization by Halide Coordination.

The development of transition metal-catalyzed reactions relies on the careful selection of appropriate ligands to enhance reactivity and stabilize intermediates. In many cross-coupling reactions, strong σ-donor and π-acceptor ligands, such as terpyridine (terpy),17 bipyridine (bpy),18−20 1,10-phenanthroline (phen),18 pyridine-bis(oxazoline) (pybox),21 α-diimine,22 and pyridine-oxazoline (pyrox),23 have proven instrumental. These ligands can be redox-active, allowing for the stabilization of low-valent nickel radical species by delocalizing the unpaired electron into the π* orbital of the ligand.24 This redox activity plays a pivotal role in promoting radical pathways and differentiates the reactivity of nickel catalysts from the traditional two-electron pathways mediated by palladium catalysts. The lack of redox activity in ligands can lead to significant differences in the redox potentials of the nickel intermediates, resulting in notable changes in the reaction mechanism.25 Therefore, it is crucial to characterize the redox activity of ligands with respect to various nickel intermediates for comprehensive understanding of the reaction mechanism and informing catalyst optimization.

Moreover, the presence of anionic ligands can influence the speciation, complexation, and electronic structure of catalytic nickel intermediates, adding complexity to the catalyst effect and the mechanistic profile (Scheme 1). Additives such as MgCl2 and KI have proven crucial in promoting catalytic reactions, such as cross-electrophile coupling reactions.14 While recent studies have started to elucidate the beneficial effects of additives on these reactions,26 the influence of anionic ligands on the electronic structure of nickel radical species and, consequently, the stability and reactivity of nickel intermediates remains unexplored.

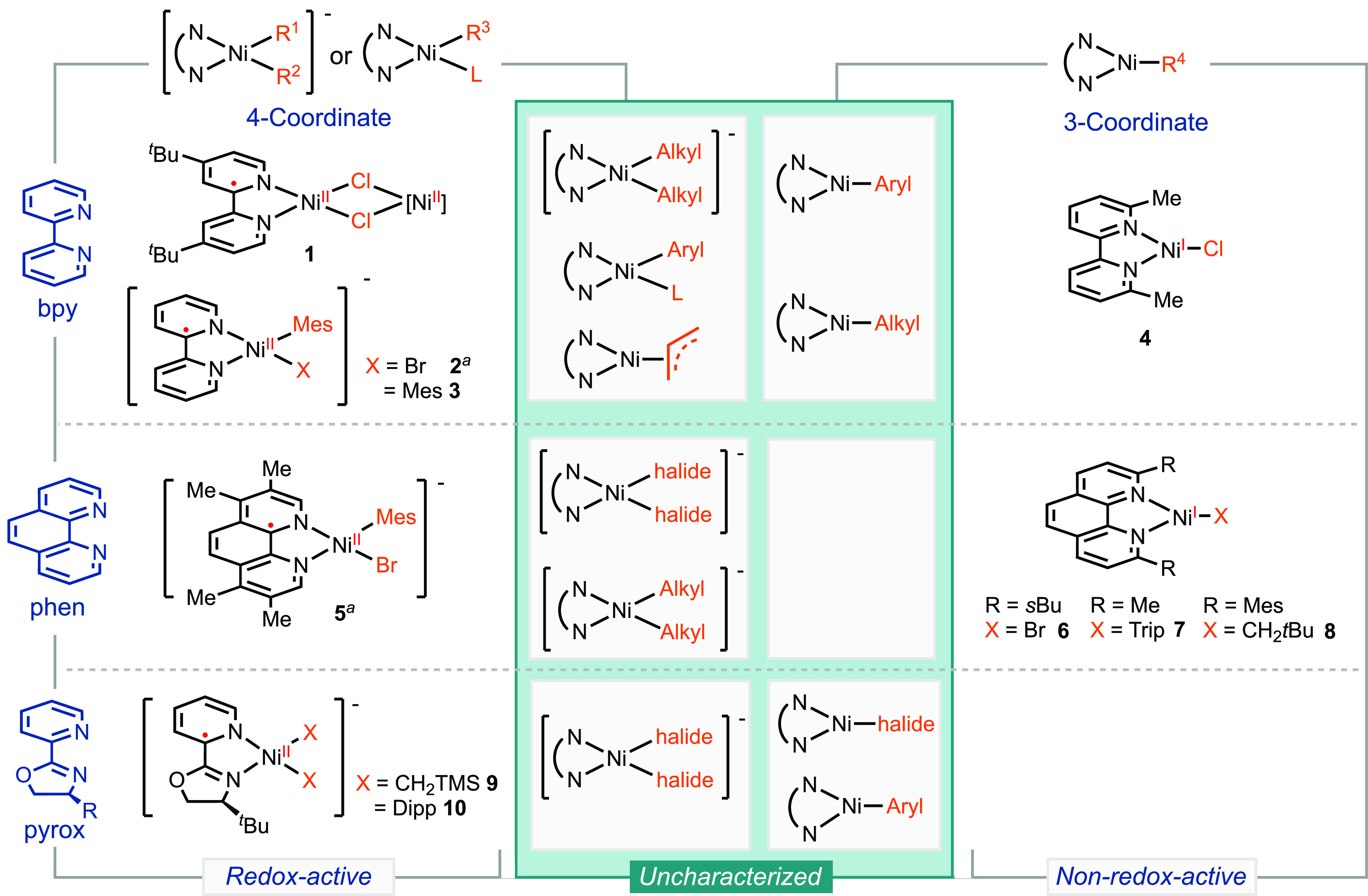

Surveying organometallic studies on nickel radical complexes ligated with bidentate N-ligands reveals that the redox activity of a ligand can vary among different complexes (Scheme 2, Table S1). The well-defined four-coordinate [(dtbpy)Ni(μ-Cl)]21 (dtbpy = 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine) adopts a distorted square-planar geometry with a dihedral angle of 26.3° (0° for square planar and 90° for tetrahedral) and has been characterized as a Ni(II) complex ligated with [dtbpy]•–.18 Similarly, two other four-coordinate nickel radical complexes, [(bpy)Ni(Mes)(Br)]− (Mes = 2,4,6-mesityl) 2(19) and [(bpy)Ni(Mes)2]−3,20 feature redox-active ligands. In contrast, the three-coordinate (Mebpy)NiCl 4 (Mebpy = 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bpy) exhibits a nickel-centered radical, with Mebpy being non-redox-active.27 In other examples, the formation of oligomers can alter the geometry of the complexes and impact the assignment of the electronic structure.13,28

Scheme 2. Electronic Structures of Precedent and Uncharacterized Organonickel Radical Complexes.

Structure characterization by X-ray crystallography is not available.

Phen-ligated nickel complexes also display variations in redox activity. [(Tmphen)Ni(Mes)Br]−5 (tmphen = 3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10-phenanthroline) has been characterized as redox-active based on electrochemical and spectroscopic studies,19,29 while three-coordinate nickel complexes, such as 6,147,30 and 8,18 exhibit nickel-centered radicals. However, the investigation of pyrox complexes remains limited, with only (pyrox)Ni complexes, 9 and 10,27 having been fully characterized as ligand-centered radicals. A comprehensive study on three-coordinate (pyrox)Ni-halide and -aryl/alkyl complexes is still lacking.

A common perception is that the redox activity of a ligand is influenced by the nature of the actor ligands. Strong-field ligands, such as alkyl and aryl groups, can promote redox activity of the auxiliary ligands, whereas weak-field ligands, such as halides, are expected to result in nonredox activity of the auxiliary ligands.31,32 Data summarized in Scheme 2, however, reveal a potential correlation between the redox activity of a ligand and the coordination number and geometry of the complexes. Four-coordinate, square-planar complexes demonstrate ligand redox activity, whereas the same ligands in three-coordinate complexes do not display redox activity. Nevertheless, several classes of nickel radical complexes lack structural characterization, which prevents the verification and generalization of this postulate. Such uncharacterized molecules include three-coordinate (bpy)Ni-aryl and -alkyl complexes, four-coordinate (phen)Ni-dihalide and -dialkyl complexes, and three-coordinate (pyrox)Ni-halide and -aryl complexes (Scheme 2).

To address this knowledge gap, this report presents a synthesis and spectroscopic study focused on the electronic structures of nickel radical complexes. By completing the missing pieces and expanding the series of organonickel radical complexes, we provide compelling evidence that establishes the correlation between the redox activity of the ligand and the geometry and coordination number of nickel radical complexes bearing bidentate N-ligands. This finding is significant as the coordination number and geometry of nickel complexes can be modulated by the selection of reaction conditions and additives. Insights into the electronic structures of the active intermediates will inform the development and optimization of catalysts.

Results

Bpy-Ligated Nickel Radical Complexes

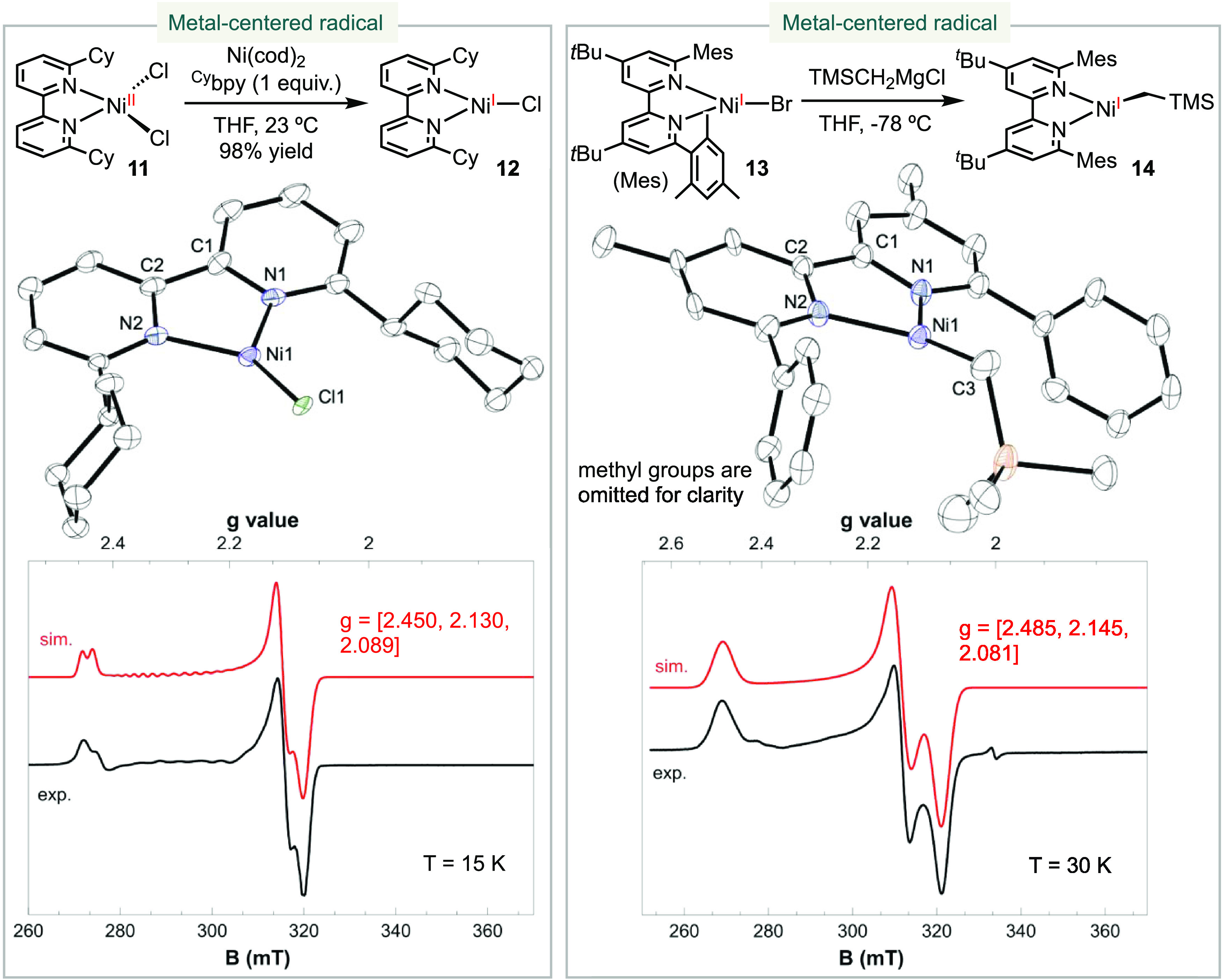

Our investigation focused on characterizing the electronic structures of three-coordinate (bpy)Ni(I)-halide, -alkyl, and -aryl complexes. We first synthesized 6,6′-dicyclohexyl-2,2′-bpy (Cybpy) and the corresponding (Cybpy)NiCl211, with the hypothesis that the steric bulkiness of Cybpy could stabilize a three-coordinate Ni(I) halide (Scheme 3). Comproportionation of (Cybpy)NiCl211 with Ni(cod)2 in the presence of Cybpy generated (Cybpy)NiCl 12 as an emerald crystalline solid in 98% yield. Single-crystal X-ray crystallography analysis confirmed a trigonal planar geometry, similar to the previously reported analogous complex (Mebpy)NiCl 4.27 The bond angles of N1–Ni–Cl and N2–Ni–Cl were determined to be 136.99(13) and 139.58(13)°, respectively, indicating a symmetrical structure. However, the dihedral angel of N1–Ni–N2–Cl was measured to be 170.8°, revealing a slight deviation from perfect trigonal planar geometry. The EPR spectrum of 12 at 15 K exhibited a rhombic signal with g values of [2.450, 2.130, 2.089], consistent with a nickel-centered radical.

Scheme 3. Synthesis and Characterization of Three-Coordinate (bpy)Ni(I)-Halide and -Alkyl Complexes.

Subsequently, we synthesized (Mesbpy)Ni(I) bromide 13 (Mesbpy = 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-6,6′-dimesityl-2,2′-bpy) as a dark yellow-green complex through the same comproportionation reaction between Ni(cod)2 and (Mesbpy)NiBr2. While 13 decomposed upon storage at room temperature, immediate transmetalation of TMSCH2MgCl with 13 led to the formation of (Mesbpy)Ni(CH2TMS) 14 as an orange solid (Scheme 3). The dihedral angles of N1–N2–Ni–C3 were 165.70 and 165.99°. Despite the disorder, both dihedral angles are comparable and suggest a slightly distorted trigonal planar geometry. This geometry resembles that of compound 7, which exhibited a N1–N2–Ni–C3 dihedral angle of 167.84°.30 The EPR spectrum of 14 at 30 K displayed a rhombic signal with g values of [2.485, 2.145, 2.081], indicating a nickel-centered radical.

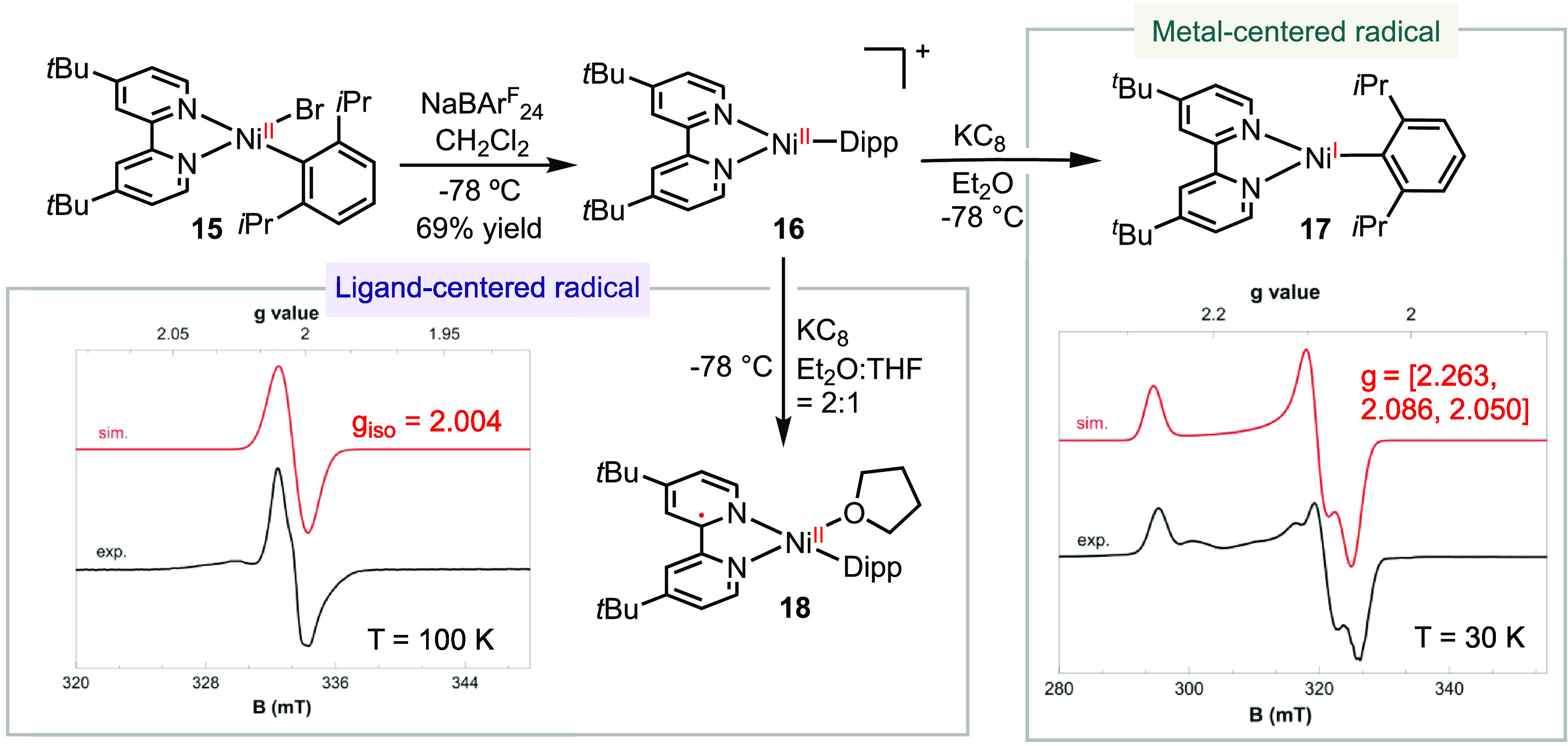

We then investigated the electronic structure of radical (bpy)Ni-aryl derivatives. Previous electrochemical and spectrochemical studies suggested the formation of four-coordinate, halide-bound species from the one-electron reduction of Ni(II) aryl halide complexes, but structural characterization was insufficient.19 Our attempts to isolate such an intermediate by chemically reducing (bpy)Ni(Mes)Br or (dtbpy)Ni(Mes)Br resulted in decomposition, leading to the formation of bis-mesityl Ni(II) complexes. Therefore, we adopted a different approach by abstracting the halide from nickel(II) aryl halide complexes prior to reduction. By oxidative addition of DippBr (Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl) to Ni(cod)2 in the presence of dtbpy, we successfully generated (dtbpy)Ni(Dipp)(Br) 15 as a dark red complex with a yield of 66% (Scheme 4). Alternatively, 15 could be synthesized through transmetalation of DippMgBr with (dtbpy)Ni(acac)2, resulting in a similar yield. Treatment of 15 with NaBAr24F (BAr24F = tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)borate) in dichloromethane resulted in bromide abstraction and the formation of the cationic [(dtbpy)Ni(II)Dipp]+[BAr24F]− complex 16. This assignment was supported by observed shifts in the 1H NMR resonances (Figure S29) and HRMS data, confirming the absence of bromide in the resulting molecule.

Scheme 4. Electronic Structures of [(bpy)Ni(I)-Aryl] Radical Complexes and the Effect of Solvent Coordination.

The reduction of 16 with KC8 at −78 °C in Et2O generated an olive-green species 17 (Scheme 4). The EPR spectrum of 17 at 30 K exhibited a rhombic signal with g values of [2.263, 2.086, 2.050]. In contrast, when the reduction by KC8 was conducted in the presence of THF as a cosolvent, the resulting product 18 appeared as a darker forest green solution compared to 17. The EPR spectrum of 18 displayed an isotropic signal with a giso value of 2.004 at 100 K. These distinct EPR data suggest that 17 corresponds to a nickel-centered radical, while 18 is a ligand-centered radical.

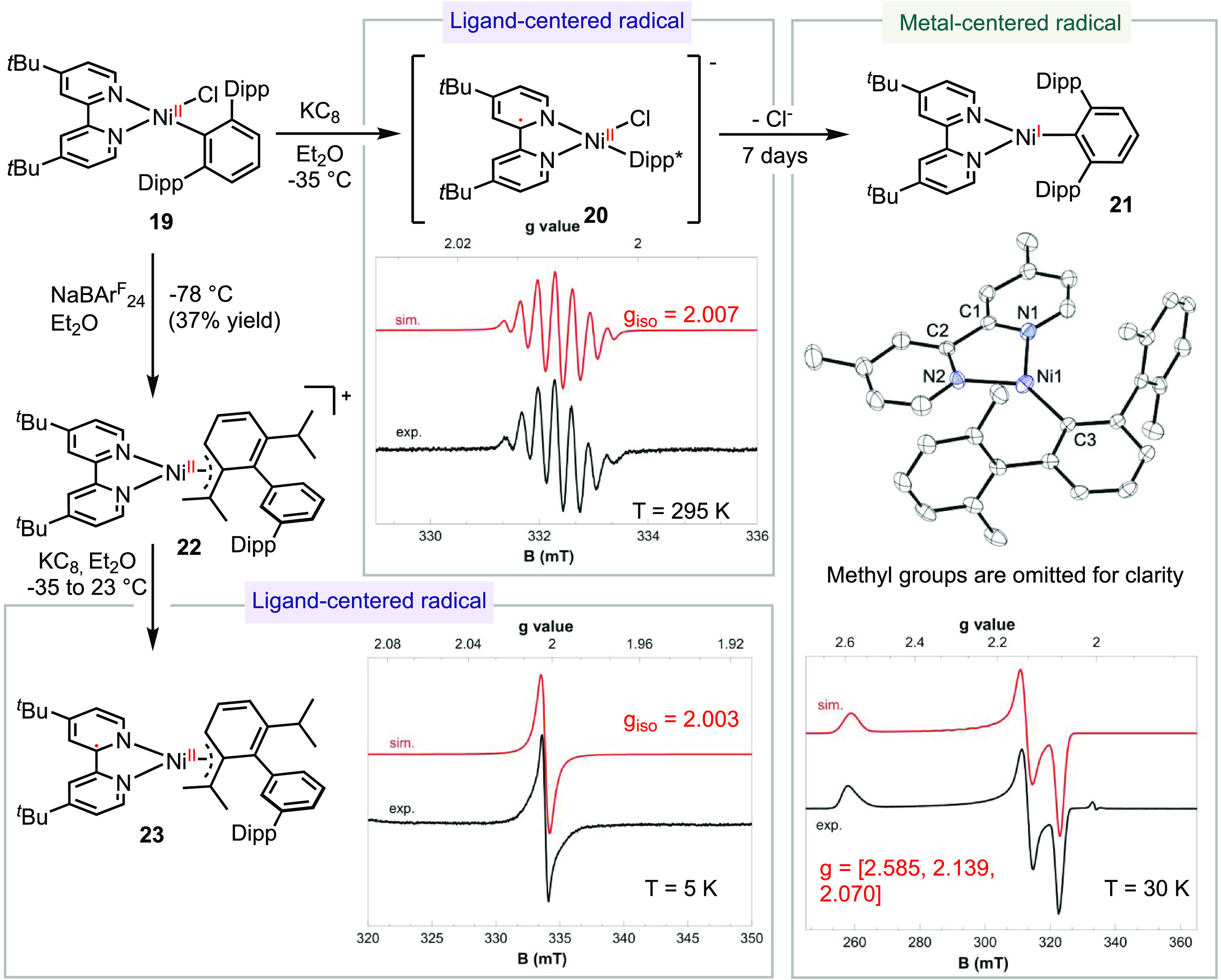

To further investigate the electronic structures of (dtbpy)Ni-aryl radical complexes, we employed a bulkier aryl ligand, 2,6-bis-Dipp-phenyl (Dipp*), to stabilize the complexes without introducing substituents on dtbpy (Scheme 5). We successfully synthesized (dtbpy)Ni(Dipp*)Cl 19 by adding (Dipp*)Li to [(dtbpy)Ni(μ-Cl)]2.12,33 Reduction of 19 with KC8 yielded intermediate 20, as a forest green solution. The EPR spectrum of 20 exhibited an isotropic signal at 295 K with a giso value of 2.007, indicating a ligand-centered radical. The observed hyperfine splitting was attributed to the coupling of the radical with two N- and two H-atoms on the dtbpy ligand. Further crystallization of a solution of 20 in pentane led to the formation of a new species 21. X-ray crystallography established that 21 was a tri-coordinate (dtbpy)Ni(Dipp*) complex with a trigonal planar geometry (Scheme 5). The dihedral angles of N1–N2–Ni–C3 in the two crystallographically unique molecules were measured to be 171.12° and 158.37°. The EPR spectrum of 21 at 30 K exhibited a rhombic signal with g values of [2.585, 2.139, 2.070]. Based on the structure of 21 and a comparison of the EPR spectra of 20 and 21, we assigned the structure of 20 as the (dtbpy)Ni(Dipp*)Cl radical anion, featuring a ligand-centered radical coordinated to a Ni(II) center.

Scheme 5. Synthesis and Characterization of Three- and Four-Coordinate (bpy)Ni(I)-Aryl and -Allyl Complexes.

Our attempt to abstract chloride from 19 using 1 equiv of NaBAr24F resulted in the formation of a π-allyl Ni(II) cationic species 22. The structure of 22 was determined through single-crystal X-ray crystallography, revealing that Dipp* underwent a rearrangement to form η3-coordination, possibly via a 1,5-H shift (cf. Figure S69). Reduction of 22 with KC8 generated complex 23. The isotropic EPR signal of 23, with a giso value of 2.003, led us to assign its electronic structure as a π-allyl Ni(II) complex coordinated by [dtbpy]•–.

We also investigated the electronic structure of (bpy)Ni-dialkyl radical complexes by conducting the reduction of their Ni(II) analogues (Scheme 6). By adding 2 equiv of TMSCH2Li to (dtbpy)NiBr224 in a mixture of THF and pentane, we obtained (dtbpy)Ni(CH2TMS)225 in a yield of 62% as a dark green solid. Further reduction of 25 with KC8 in THF in the presence of 18-crown-6 furnished [(dtbpy)Ni(CH2TMS)2]-[18-crown-6(K)]+26 as a dark red crystalline solid. The single-crystal X-ray structure of 26 displayed a square-planar geometry, reminiscent of a previously reported analogous complex, [(tBupyrox)Ni(CH2TMS)2]-[18-crown-6(K)]+9.23 The EPR spectrum of complex 26 exhibited an isotropic signal with a giso value of 2.006 and showed hyperfine splitting, which was attributed to the interaction of the radical with two N- and two H-atoms. Therefore, we assigned the electronic structure of complex 26 as a ligand-centered radical coordinated to a Ni(II) center.

Scheme 6. Electronic Structure of the Four-Coordinate (dtbpy)Ni-Dialkyl Radical Anion Complex.

The collective analysis of EPR data and single-crystal X-ray diffraction crystallography allowed for the unambiguous assignment of the electronic structures of a series of (bpy)Ni radical complexes (Table 1). Complexes 12, 14, 17, and 21, characterized as three-coordinate trigonal planar complexes, exhibited rhombic EPR signals at low-temperatures, with g values reflecting nickel-centered radicals. The bond lengths of the Cpy–Npy and the Cpy–Cpy bonds in these complexes were similar to those observed in the (bpy)Ni(II) complex 19, indicating the lack of redox activity of the bpy ligands in 12, 14, 17, and 21. In contrast, complexes 18, 20, 23, and 26, identified as four-coordinate square-planar complexes, displayed EPR spectra indicative of organic radicals at higher temperatures, suggesting the presence of ligand-centered radicals. Notably, the Cpy–Npy bond lengths in 26 were elongated compared to the nickel(I) complexes, while the Cpy–Cpy bond length was considerably shorter. Based on these observations, we assigned the electronic structures of 18, 20, 23, and 26 as nickel(II)-ligated with [bpy]•–.

Table 1. EPR and Single-Crystal X-ray Structure Parameters of (bpy)Nickel Complexes.

| complex | g values of the EPR signal | C1–N1 and C2–N2 (Npy–Cpy) (Å) | C1–C2 (Cpy–Cpy) (Å) | location of the radical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 2.450, 2.130, 2.089 | 1.359(6), 1.361(6) | 1.466(7) | metal |

| 14 | 2.485, 2.145, 2.081 | 1.364(2), 1.364(2) | 1.484(3) | metal |

| 17 | 2.263, 2.086, 2.050 | metal | ||

| 18 | 2.004 | ligand | ||

| 19a | 1.364(3), 1.348(3); 1.364(3), 1.341(3) | 1.472(3); 1.473(3) | ||

| 20 | 2.007 | ligand | ||

| 21a | 2.585, 2.139, 2.070 | 1.354(5), 1.342(5); 1.353(5), 1.343(5) | 1.470(5); 1.472(6) | metal |

| 23 | 2.003 | ligand | ||

| 26 | 2.006 | 1.387(3), 1.383(4) | 1.414(4) | ligand |

Two crystallographically independent molecules.

Phen-Ligated Nickel Radical Complexes

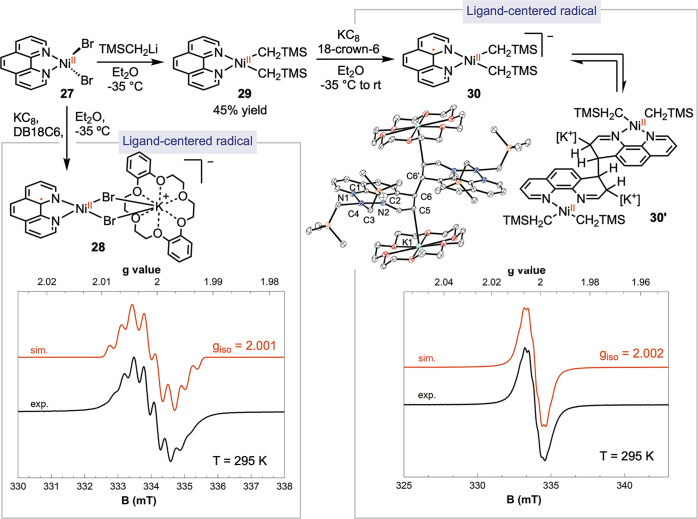

Phen has commonly been considered as a bpy analogue in the advancement of catalytic reactions. However, the conjugation between the two pyridine rings in phen can substantially influence its redox potentials.34 While a few examples of three-coordinate phen-ligated Ni(I) complexes have been documented,12,18,30 our investigation focused on the relatively unexplored four-coordinate phen radical complexes (Scheme 7). The reduction of (phen)NiBr227 with KC8 in the presence of dibenzo-18-crown-6 (DB18C6) yielded a dark violet species, 28. The EPR spectrum displayed the presence of an organic radical with a giso value of 2.001 and hyperfine couplings corresponding to the interaction of the radical with two N- and one H-atoms. Despite some similarities with [phen]•–, the EPR signal of 28 exhibited more pronounced line-broadening, which can be attributed to the quadrupole moment of bromide, leading to faster relaxation.35 The EPR signal, including both intensity and hyperfine pattern, was significantly influenced by the nature of the crown ether, suggesting the association of [crown]K+ with 28 (cf. Figures S58 and S59). The stability of 28 closely correlated with the nature of the halide, as the complex rapidly decomposed when bromide was replaced with chloride. Unfortunately, our attempts to obtain a single crystal of 28 were unsuccessful due to its instability. Based on the analysis of the available evidence, we tentatively propose the structure of 28 as a four-coordinate complex, [K(DB18C6)]+[(phen)NiBr2]−, where the Ni(II) complex is ligated with a phen-centered radical.

Scheme 7. Synthesis and Electronic Structures of Four-Coordinate (phen)Nickel Radical Complexes.

The transmetalation of 27 with TMSCH2Li resulted in the formation of (phen)Ni(CH2TMS)229, a navy blue solid with a yield of 47%. Reduction of 29 with 1 equiv of KC8 in the presence of 18-crown-6 in Et2O produced a dark teal solution, 30. The EPR spectrum of 30 in THF at 295 K displayed an isotropic signal with a giso value of 2.002, accompanied by hyperfine coupling corresponding to the interaction of the radical with two N- and two H-nuclei. We assigned the structure of 30 as [(18-crown-6)K]+[(phen)Ni(CH2TMS)2]−. Single-crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed a dimeric structure, 30′, where a single bond was formed between the carbons at the 4-positions of two phen ligands (C6–C6′ = 1.594(7) Å). Additionally, there was a close interaction between the carbon at the 3-position (C5) of phen and [K(18-crown-6)]+, evidenced by a C–K distance of 3.105(4) Å. The formation of bonds between C6, C5, and K disrupted aromaticity, resulting in a puckered geometry of the pyridine ring involved in the bond formation, reflecting sp3 hybridization of C5 and C6.

The presence of a spin = 1/2 nickel species and the X-ray structure of the dimer indicated an equilibrium between 30 and 30′. The facile formation and cleavage of the C–C bond between the two phen ligands at the 4-position align with the electronic structure of [phen]•– Ni(II) and highlight the significant population of the radical at the 4-position of phen.

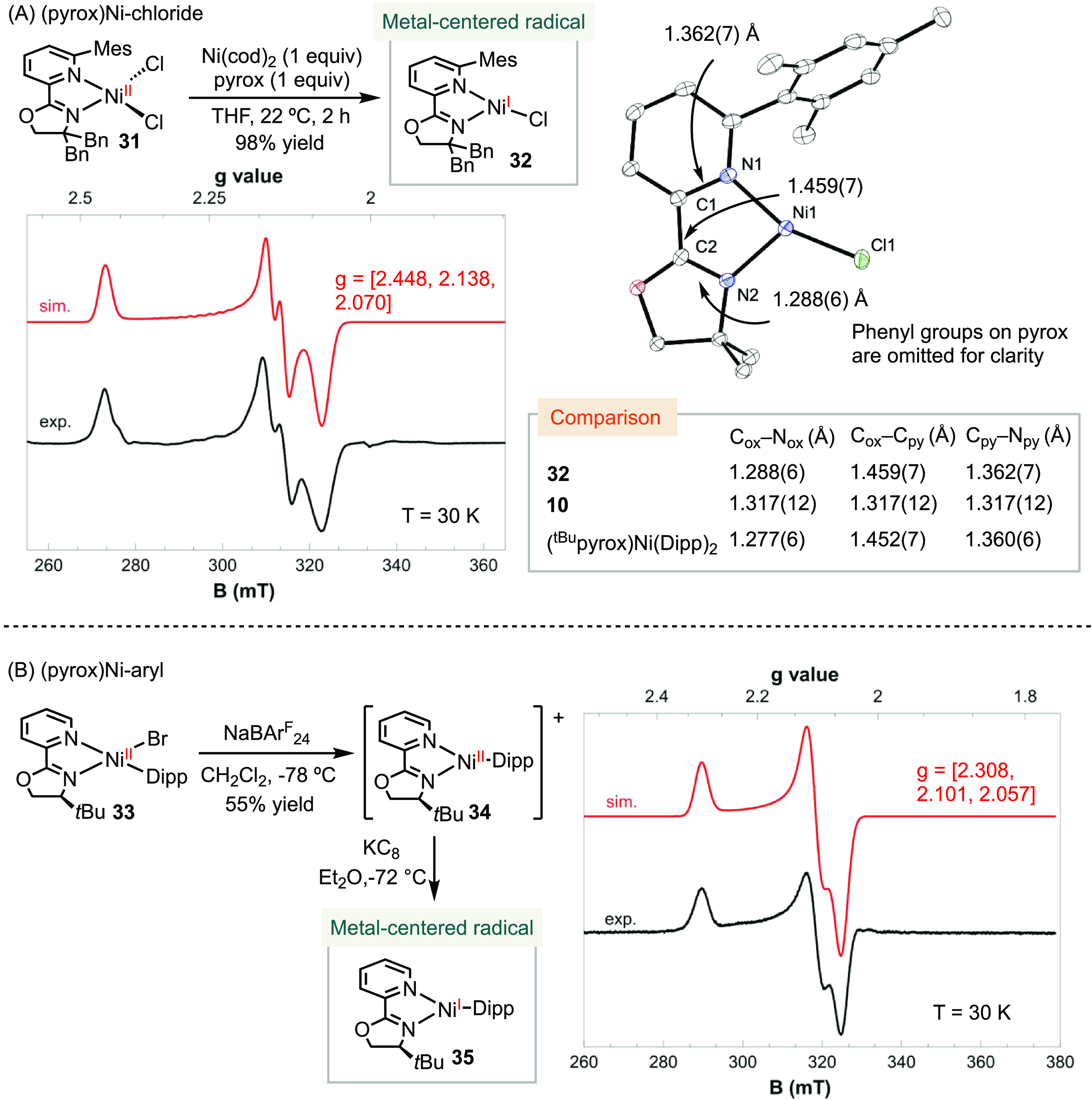

Pyrox-Ligated Nickel Radical Complexes

We conducted further investigations on tri-coordinate (pyrox)Ni radical complexes, which have received limited attention in previous studies.23 Our previous attempts in their synthesis encountered challenges due to the relatively facile dissociation of pyrox compared to bpy or phen, resulting in the formation of undesired (pyrox)2Ni complexes. To stabilize the molecules, we introduced di-benzyl substituents on the oxazoline and a mesityl group on the pyridine to increase the steric bulk of the pyrox ligand (Scheme 8A). By comproprotionation of (pyrox)NiCl231 and Ni(cod)2, we successfully synthesized (pyrox)NiCl 32 in 98% yield as a forest green crystalline solid. The X-ray crystal structure of 32 revealed an intriguing T-shape geometry with bond angles of N1–Ni–Cl of 118.07(13)° and N2–Ni–Cl of 158.38(14)°, which can be attributed to the unsymmetrical trans-influence of the pyridine and oxazoline motifs. The Cox–Nox, Cox–Cpy, and Cpy–Npy bond lengths were determined as 1.288(6), 1.459(7), and 1.362(7) Å, respectively, comparable to those observed in (tBupyrox)Ni(Dipp)2.23 In contrast, the Cox–Nox and Cpy–Npy bonds of 10, a pyrox radical anion, are notably longer, while the Cox–Cpy bond is shorter compared to those in 32. The EPR spectrum of 32 exhibited a rhombic signal at 30 K, with g values of [2.448, 2.138, 2.070]. By comparing the bond lengths of 32 to (tBupyrox)Ni(Dipp)2 and 10 and considering the observation of a nickel(I) radical in EPR spectroscopy, we concluded that 32 is best described as a nickel-centered radical with a non-redox-active pyrox ligand.

Scheme 8. Synthesis and Characterization of Three-Coordinate (pyrox)Ni Radical Complexes.

Lastly, we employed NaBAr24F to abstract the bromide from (tBupyrox)Ni(Dipp)(Br) 33, resulting in the formation of complex 34 using a similar synthetic protocol as in the preparation of 16 (Scheme 8B). The reaction led to a color change from maroon to amber. The 1H NMR spectra of 34 exhibited upfield shifts compared to those of 33 (Figure S45). HRMS analysis of 34 revealed an exact mass of 424.2081 (M-BAr24F + H), indicating the absence of the bromide ion. In contrast, HRMS of 33 displayed a mass of 525.1379 (M + Na). Based on these findings, we assigned complex 34 as the cationic [(tBupyrox)Ni(Dipp)]+[BAr24F]−. Further reduction of 34 with KC8 yielded a dark green solution, and the corresponding EPR spectrum displayed a rhombic signal with g values of [2.308, 2.101, 2.057]. We assigned the structure of 35 to a three-coordinate [(tBupyrox)Ni(Dipp)] complex as a nickel-centered radical.

DFT Calculations

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations on the electronic structures of the nickel radical complexes described in this study. The geometry optimization was found to be highly sensitive to the functional and the basis set. While the commonly used basis set, (U)B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVPP, was successful in reproducing the experimental geometries of [NiR2]− and NiX complexes, it performed poorly with Ni–Ar and [NiX]2 complexes. As a result, we applied the combination of (U)B3LYP//m6-31g* for the Ni–Ar complexes.31 In general, the electronic structures obtained from DFT calculations are consistent with experimental data. The four-coordinate complexes were computed to be square planar with highly delocalized spin density on the ligands, and the ligand C=N bonds were elongated (Figures S75 and S77–S80). Among the three-coordinate Ni(I) complexes, the Ni(I)-halide and Ni(I)-phenyl complexes were computed to be trigonal planar with localized spin density on the Ni centers (Figures S73, S74, S76, S81, and S82).

Discussion

In this study, we synthesized a series of nickel radical complexes and characterized their electronic structures using NMR, EPR, mass spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography. These new complexes highlighted in red in Scheme 9A, complete the range of nickel radical analogues, allowing us to draw empirical conclusions regarding the correlation between coordination geometry and redox activity of the ligand. In general, four-coordinate nickel radical complexes adopting a square-planar geometry can be best described as low-spin nickel(II) complexes coordinated with ligand radical anions. In contrast, three-coordinate nickel-halide, -alkyl, and -aryl complexes adopt trigonal planar or distorted trigonal planar geometries. These molecules are characterized as nickel(I) centers coordinated with non-redox-active ligands. This pattern remains consistent regardless of the identity of the X-ligands.

Scheme 9. Electronic Structures of Nickel Radical Complexes (A) and the Comparison of SOMO Energy Levels in Different Geometries (B).

While tetrahedral nickel radical complexes are beyond the scope of this study, several such molecules have been reported within the α-diimine ligand framework, including [(α-diimine)Ni(μ-H)]2 and [(α-diimine)Ni(μ-halide)]2 complexes.22 In contrast to square-planar nickel complexes, most of these tetrahedral molecules are characterized as nickel-centered radicals, where the α-diimine ligand does not exhibit redox activity.

Based on the data presented in this report and literature precedents, we propose that the redox activity of bidentate N-ligands in low-valent organonickel radical complexes is dependent on the geometry and coordination number. The redox activity of the ligand is determined by the relative energy levels of the unfilled d orbital and the π* orbital of the ligand (Scheme 9B). Molecules of trigonal planar and tetrahedral geometries have relatively low-energy antibonding d orbitals, which can be lower than the π* orbital of the ligand. Consequently, the unpaired electron tends to occupy the d orbital, resulting in a d9 electronic configuration. In contrast, square-planar complexes have high-energy dx2–y2 orbitals. In this geometry, the unpaired electron prefers to occupy the π* orbital of the ligand, leading to a nickel(II) center coordinated with a radical anion ligand.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting this hypothesis is the contrasting electronic structures of 17 and 18 (Scheme 4). Introducing a coordinating solvent to shift the coordination number from three to four resulted in changes in both the redox activity of the ligand and the oxidation state of the nickel center. These results have significant implications for catalyst optimization. In nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, various additives such as MgCl2 and KI, have been extensively employed. Besides their role in modulating the speciation of active nickel catalysts, which has recently been elucidated,26 the presence of coordinating anions may also play a crucial role in stabilizing nickel(I) intermediates and tuning the redox potentials by inducing ligand redox activity. Furthermore, our data suggest that the use of coordinating solvents may benefit the reaction by exerting a similar stabilization effect.

An exception to this postulate has been reported before: a square-planar (terpy)Ni-methyl complex exhibits a ligand-centered radical, whereas square-planar (terpy)Ni-bromide31 and (terpy)Ni-phenolate32 complexes display metal-centered radicals. This observation may be attributed to various factors, including a relatively low-lying dx2-y2 orbital with weak-field ligands, the rigid geometry of terpy that precludes alternative geometries other than square-planar, or potential π-stacking effects caused by the planar terpy ligand. Ongoing research endeavors aim to further elucidate the underlying factors governing ligand redox activity of tridentate ligands.

Conclusions

We have synthesized and characterized a series of nickel radical complexes that hold significant catalytic relevance. This comprehensive collection of complexes includes various (bpy), (phen), and (pyrox)nickel radical analogues, which enable us to establish a clear correlation between the coordination geometry and the redox activity of the ligands. Specifically, the four-coordinate square-planar nickel radical complexes are low-spin nickel(II) centers coordinated with radical anion ligands. In contrast, the three-coordinate nickel radical complexes exhibit a trigonal planar geometry, featuring nickel(I) centers coordinated with ligands that do not display redox activity. This trend remains consistent regardless of the identity of the X-ligands. These findings provide an account for the important role of coordinating salt additives and solvents in modulating the stability and redox potentials of nickel intermediates by altering the coordination number and inducing ligand redox activity. This understanding of the relationship between the coordination environment and ligand redox properties is crucial for the design and optimization of catalysts in the development of nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

Acknowledgments

G.A.D. is grateful for the NYU X-ray diffraction facility for determining several crystal structures. This work is supported by the National Science Foundation under Award Number 2032664. Q.L. thanks the Margaret and Herman Sokol Fellowship and the Dean’s Dissertation Fellowship. T.D. acknowledges the Camille-Dreyfus Teacher Scholar Award (TC-19-019) and the NSF (CHE-1827902) for funding to acquire the EPR spectrometer. The X-ray diffractometer at Hunter College has been funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under Award Number FA9550-20-1-0158. The DFT calculations received support from the NYU IT High Performance Computing resources, services, and staff expertise.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c07031.

Detailed experimental procedures; characterization data, such as NMR, EPR, and UV–Visible spectra; details of DFT calculations; and spin density plots (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ Department of Process Research & Development, Merck & Co., lnc., 126 E. Lincoln Avenue, Rahway, New Jersey 07065, United States

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hu X. Nickel-catalyzed cross coupling of non-activated alkyl halides: A mechanistic perspective. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1867–1886. 10.1039/c1sc00368b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Z.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.; Fu G. C. Transition metal–catalyzed alkyl-alkyl bond formation: Another dimension in cross-coupling chemistry. Science 2017, 356, eaaf7230 10.1126/science.aaf7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G. C. Transition-Metal Catalysis of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: A Radical Alternative to SN1 and SN2 Processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 692–700. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diccianni J. B.; Diao T. Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 830–844. 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diccianni J.; Lin Q.; Diao T. Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions and Applications in Alkene Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 906–919. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-Y.; Power P. P. Complexes of Ni(I): A ″rare″ oxidation state of growing importance. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5347–5399. 10.1039/C7CS00216E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P.; Limberg C. Activation of Small Molecules at Nickel(I) Moieties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4233–4242. 10.1021/jacs.6b12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuto A.; Finkelstein P.; Müller P.; Morandi B. The Journey of Ni(I) Chemistry. Helv. Chim. Acta 2021, 104, e2100177 10.1002/hlca.202100177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Cherney A. H.; Kadunce N. T.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective and Enantiospecific Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organometallic Reagents To Construct C–C Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9587–9652. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lucas E. L.; Jarvo E. R. Stereospecific and stereoconvergent cross-couplings between alkyl electrophiles. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0065. 10.1038/s41570-017-0065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. Y.; Perry I. B.; Bissonnette N. B.; Buksh B. F.; Edwards G. A.; Frye L. I.; Garry O. L.; Lavagnino M. N.; Li B. X.; Liang Y.; Mao E.; Millet A.; Oakley J. V.; Reed N. L.; Sakai H. A.; Seath C. P.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox: The Merger of Photoredox and Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1485–1542. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ting S. I.; Williams W. L.; Doyle A. G. Oxidative Addition of Aryl Halides to a Ni(I)-Bipyridine Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5575–5582. 10.1021/jacs.2c00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tang T.; Hazra A.; Min D. S.; Williams W. L.; Jones E.; Doyle A. G.; Sigman M. S. Interrogating the Mechanistic Features of Ni(I)-Mediated Aryl Iodide Oxidative Addition Using Electroanalytical and Statistical Modeling Techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 8689–8699. 10.1021/jacs.3c01726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mohadjer Beromi M.; Banerjee G.; Brudvig G. W.; Hazari N.; Mercado B. Q. Nickel(I) Aryl Species: Synthesis, Properties, and Catalytic Activity. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2526–2533. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Diccianni J. B.; Katigbak J.; Hu C.; Diao T. Mechanistic Characterization of (Xantphos)Ni(I)-Mediated Alkyl Bromide Activation: Oxidative Addition, Electron Transfer, or Halogen-Atom Abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1788–1796. 10.1021/jacs.8b13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lin Q.; Fu Y.; Liu P.; Diao T. Monovalent Nickel-Mediated Radical Formation: A Concerted Halogen-Atom Dissociation Pathway Determined by Electroanalytical Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14196–14206. 10.1021/jacs.1c05255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Weix D. J. Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp2 Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1767–1775. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xue W.; Jia X.; Wang X.; Tao X.; Yin Z.; Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed formation of quaternary carbon centers using tertiary alkyl electrophiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4162–4184. 10.1039/D0CS01107J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q.; Diao T. Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Reductive 1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17937–17948. 10.1021/jacs.9b10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q.; Spielvogel E. H.; Diao T. Carbon-centered radical capture at nickel(II) complexes: Spectroscopic evidence, rates, and selectivity. Chem 2023, 9, 1295–1308. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T. J.; Jones G. D.; Vicic D. A. Evidence for a NiI Active Species in the Catalytic Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8100–8101. 10.1021/ja0483903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MohadjerBeromi M.; Brudvig G. W.; Hazari N.; Lant H. M. C.; Mercado B. Q. Synthesis and Reactivity of Paramagnetic Nickel Polypyridyl Complexes Relevant to C(sp2)–C(sp3)Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6094–6098. 10.1002/anie.201901866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A.; Kaiser A.; Sarkar B.; Wanner M.; Fiedler J. The Electrochemical Behaviour of Organonickel Complexes: Mono-, Di- and Trivalent Nickel. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 965–976. 10.1002/ejic.200600865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M.; Doyle L. R.; Krämer T.; Herchel R.; McGrady J. E.; Goicoechea J. M. A Homologous Series of First-Row Transition-Metal Complexes of 2,2′-Bipyridine and their Ligand Radical Derivatives: Trends in Structure, Magnetism, and Bonding. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 12301–12312. 10.1021/ic301587f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schley N. D.; Fu G. C. Nickel-Catalyzed Negishi Arylations of Propargylic Bromides: A Mechanistic Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16588–16593. 10.1021/ja508718m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shao Q.; Sun H.; Shen Q.; Zhang Y. Bis{[diacetyl-bis(2,6-isopropylphenylimine)]nickel(I)(μ-chloro)}. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 18, 289–290. 10.1002/aoc.624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dong Q.; Zhao Y.; Su Y.; Su J.-H.; Wu B.; Yang X.-J. Synthesis and Reactivity of Nickel Hydride Complexes of an α-Diimine Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 13162–13170. 10.1021/ic301392p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kuang Y. L.; Anthony D.; Katigbak J.; Marrucci F.; Humagain S.; Diao T. Ni(I)-Catalyzed Reductive Cyclization of 1,6-Dienes: Mechanism-Controlled trans Selectivity. Chem 2017, 3, 268–280. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Zarate C.; Yang H.; Bezdek M. J.; Hesk D.; Chirik P. J. Ni(I)–X Complexes Bearing a Bulky α-Diimine Ligand: Synthesis, Structure, and Superior Catalytic Performance in the Hydrogen Isotope Exchange in Pharmaceuticals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5034–5044. 10.1021/jacs.9b00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C. L.; Herrera G.; Lin Q.; Hu C. T.; Diao T. Redox activity of Pyridine-Oxazoline Ligands in the Stabilization of Low-Valent Organonickel Radical Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5295–5300. 10.1021/jacs.1c00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lu C. C.; Bill E.; Weyhermüller T.; Bothe E.; Wieghardt K. Neutral Bis(α-iminopyridine)metal Complexes of the First-Row Transition Ions (Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn) and Their Monocationic Analogues: Mixed Valency Involving a Redox Noninnocent Ligand System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3181–3197. 10.1021/ja710663n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chirik P. J.; Wieghardt K. Radical Ligands Confer Nobility on Base-Metal Catalysts. Science 2010, 327, 794–795. 10.1126/science.1183281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chirik P. J. Preface: Forum on Redox-Active Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9737–9740. 10.1021/ic201881k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Luca O. R.; Crabtree R. H. Redox-active ligands in catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1440–1459. 10.1039/C2CS35228A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e de Bruin B.; Gualco P.; Paul N. D.. Redox Non-innocent Ligands. In Ligand Design in Metal Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, 2016; pp 176–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ju L.; Lin Q.; LiBretto N. J.; Wagner C. L.; Hu C. T.; Miller J. T.; Diao T. Reactivity of (bi-Oxazoline)organonickel Complexes and Revision of a Catalytic Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14458–14463. 10.1021/jacs.1c07139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C. S.; Rentería-Gómez Á.; Ton S. J.; Gogoi A. R.; Gutierrez O.; Martin R. Elucidating electron-transfer events in polypyridine nickel complexes for reductive coupling reactions. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 244–253. 10.1038/s41929-023-00925-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey E. L. B. J.; Kennedy A. R.; Sproules S.; Nelson D. J. Evaluating a Dispersion of Sodium in Sodium Chloride for the Synthesis of Low-Valent Nickel Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101006 10.1002/ejic.202101006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R.; Qin Y.; Ruccolo S.; Schnedermann C.; Costentin C.; Nocera D. G. Elucidation of a Redox-Mediated Reaction Cycle for Nickel-Catalyzed Cross Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 89–93. 10.1021/jacs.8b11262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakhvarov D. G.; Petr A.; Kataev V.; Büchner B.; Gómez-Ruiz S.; Hey-Hawkins E.; Kvashennikova S. V.; Ganushevich Y. S.; Morozov V. I.; Sinyashin O. G. Synthesis, structure and electrochemical properties of the organonickel complex [NiBr(Mes)(phen)] (Mes = 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl, phen = 1,10-phenanthroline). J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 750, 59–64. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville R. J.; Odena C.; Obst M. F.; Hazari N.; Hopmann K. H.; Martin R. Ni(I)–Alkyl Complexes Bearing Phenanthroline Ligands: Experimental Evidence for CO2 Insertion at Ni(I) Centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10936–10941. 10.1021/jacs.0c04695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciszewski J. T.; Mikhaylov D. Y.; Holin K. V.; Kadirov M. K.; Budnikova Y. H.; Sinyashin O.; Vicic D. A. Redox Trends in Terpyridine Nickel Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 8630–8635. 10.1021/ic201184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuto A.; Müller P.; Finkelstein P.; Trapp N.; Jeschke G.; Morandi B. One to Find Them All: A General Route to Ni(I)–Phenolate Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10642–10648. 10.1021/jacs.1c03763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski C. A.; Bungum D. J.; Baldwin S. M.; Del Ciello S. A.; Iluc V. M.; Hillhouse G. L. Synthesis and Reactivity of Two-Coordinate Ni(I) Alkyl and Aryl Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18272–18275. 10.1021/ja4095236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q.; Dawson G.; Diao T. Experimental Electrochemical Potentials of Nickel Complexes. Synlett 2021, 32, 1606–1620. 10.1055/s-0040-1719829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandleben A.; Vogt N.; Hörner G.; Klein A. Redox Series of Cyclometalated Nickel Complexes [Ni((R)Ph(R′)bpy)Br]+/0/–/2– (H–(R)Ph(R′)bpy = Substituted 6-Phenyl-2,2′-bipyridine). Organometallics 2018, 37, 3332–3341. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.