Abstract

Nausea and vomiting are cardinal symptoms affecting many patients with delayed or normal gastric emptying. The current therapies are very limited and less than optimal. Therefore, gastrointestinal symptoms persist despite using all the standard approaches for gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, or unexplained nausea and vomiting. It is well established that gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is effective in reducing nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis, but there are essentially no data available that detail the efficacy of GES in symptomatic patients without gastroparesis. We present a unique case of a female patient diagnosed with functional dyspepsia, whose nausea and vomiting which were refractory to all standard therapies were successfully addressed with the implantation of a GES system.

Keywords: gastric electrical stimulation, nausea, vomiting, functional dyspepsia

Introduction

The prevalence of dyspepsia in the general population is approximately 20%. 1 Characteristic symptoms include epigastric pain and burning, postprandial fullness and nausea, or early satiety occurring for at least 6 months. Rome IV criteria are used in diagnosing functional dyspepsia (FD), and this is divided into 2 subgroups: epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome. 2 Gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved bioelectric therapy used for drug-refractory gastroparesis due to diabetes or from an idiopathic origin. 3 Off-label uses of GES have been published in symptomatic patients with postsurgical gastroparesis, and also there are a few reports in the setting of normal gastric emptying. 3 Herein, we present a case of a 29-year-old female with refractory nausea and vomiting which were treated with the implantation of a GES system.

Case Presentation

Our patient is a 29-year-old white female who initially developed intractable nausea and vomiting occurring essentially every day for 1 year prior to presentation. Further history elucidated she had significant stressors in her personal life which led to treatment by a psychiatrist for anxiety and depression. Due to an ongoing weight loss of 60 lbs, a J tube was placed laparoscopically at an external facility to aid in nutrition in addition to a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube for gastric decompression. Weight stabilized but nausea and vomiting continued despite medical therapy and antiemetics over the next 8 months. Her antiemetic regimen included metoclopramide up to 60 mg daily, ondansetron, and promethazine. She was subsequently referred to our institution for further workup and management.

Upon admission in August 2022, vital signs were within normal limits, and an abdominal examination revealed hyperactive bowel sounds and a positive Carnett’s sign, which is specific for rectus abdominis muscle pain attributed to retching and vomiting. Laboratory results showed hypokalemia at 3.2. She was started on intravenous metoclopramide and a scopolamine patch. Her anxiety was addressed by lorazepam and a tricyclic antidepressant (amitriptyline). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no abnormalities including a negative Helicobacter pylori test. The findings on the endoluminal functional lumen imaging probe (ENDOFLIP) performed during the endoscopy were consistent with a widely patent pylorus with a diameter of 15.7 mm. A 4-hour scintigraphy radioisotope–labeled egg meal (Tc99) indicated that the gastric emptying was normal with a 10% retention at the 4 hours mark. In this setting of no gastroparesis and intractable nausea and vomiting, a gastric electrical pacemaker was placed laparoscopically and the J tube was removed (The G tube had been previously removed 3 months prior.). The GES parameters were an impedance of 500 Ohms, voltage of 4 V, and current of 7.2 mA. She did not have any intraoperative or postoperative complications and was subsequently discharged on the third postoperative day. On follow-up after 4 months, the patient’s weight had recovered by 35 lbs, and she was tolerating a regular diet with no vomiting and essentially complete resolution of nausea. She reported a significant improvement in her quality of life when compared with her pre-GES status.

Discussion

Functional dyspepsia is clinically diagnosed based on symptoms that include postprandial epigastric pain, epigastric burning and discomfort, and bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiation, and nausea with no evidence of any structural disease including findings on endoscopy. 2 These symptoms should be active in the past 3 months with onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. Functional dyspepsia is divided into 2 subgroups according to the Rome IV criteria: epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome. Epigastric pain syndrome involves experiencing epigastric pain and/or burning occurring at least 1 day a week for more than 1 week. Postprandial distress syndrome involves experiencing bothersome postprandial fullness and/or early satiety or nausea affecting usual daily activities at least 3 days a week. Intractable nausea and vomiting are part of the clinical spectrum of FD. Numerous epidemiological studies show that being female, smoking, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and H. pylori infection increases the risk of developing FD of the epigastric pain subtype. 1 In the postprandial category, it has been proposed that symptom generation is a complex relationship between the gut and the brain, with triggering factors such as food, stress, gut microbiota, and psychosocial comorbidities. 1 Treatment involves the eradication of H. pylori, acid suppression therapy in the epigastric pain subgroup, whereas the use of prokinetics and/or antiemetics as well as the use of central neuromodulators was the treatment pathway in the postprandial distress group.

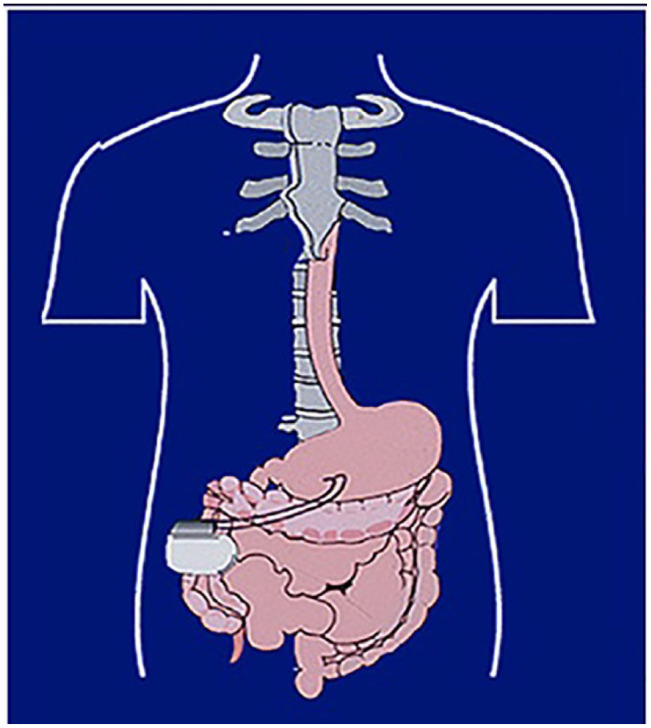

The idea of GES was based on the knowledge that the gastrointestinal tract has a network of pacemaker cells termed the Interstitial cells of Cajal which in the stomach consists of a series of electrical potentials propagated aborally in the smooth muscle of the stomach toward the pylorus at a rate of 3 cycles per minute. The GES is implanted via laparotomy or laparoscopy surgery with the leads being placed in the muscularis propria of the greater curvature of the stomach about 9 to 10 cm proximal to the pylorus (Figure 1). The GES device does not accelerate gastric emptying or “pace” the stomach by inducing a new electrical signal or induce contractions of the smooth muscle. Its mechanism of action is to stimulate afferent pathways to the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the medulla, an area including the tractus solitarius and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Nausea and vomiting are reduced by the activation of these central control mechanisms. In addition, increasing the vagal output improves the accommodation and relaxation of the proximal stomach, resulting in more oral intake. Adverse events of placement of the GES system include dislodgement and migration of the electrodes into the gastric lumen and trauma to the pulse generator pocket resulting in a hematoma or infection. 4

Figure 1.

Placement of GES system. Leads are placed 9 to 10 cm proximal to the pylorus, whereas the pulse generator is in the right or left upper quadrants of the abdomen.

Conclusions

Gastric electrical stimulation is an FDA-approved treatment for the symptoms of gastroparesis, particularly nausea and vomiting. However, there are essentially no data for its use in treatment for intractable nausea and vomiting in the setting of normal gastric emptying. Our patient is a unique example demonstrating that GES is a safe and effective treatment modality for intractable nausea and vomiting, not explained by a severe functional motility disorder.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from the patient for her anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iDs: Jeff Angelo Taclob  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7757-9087

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7757-9087

Andrew J. Ortega  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6925-9884

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6925-9884

References

- 1. Ford AC, Mahadeva S, Carbone MF, et al. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1689-1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1380-1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abell TL. Gastric electrical stimulation: overview and summary. J Transl Int Med. 2023;10(4):286-289. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2022-0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atassi H, Abell TL. Gastric electrical stimulator for treatment of gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019;29(1): 71-83. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2018.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]