Abstract

Introduction:

Mutations in the Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene cause autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease (PD) with the most common causative mutation being the LRRK2 p.G2019S within the kinase domain. LRRK2 protein is highly expressed in the human brain and also in the periphery, and high expression of dominant PD genes in immune cells suggest involvement of microglia and macrophages in inflammation related to PD. LRRK2 is known to respond to extracellular signalling including TLR4 resulting in alterations in gene expression, with the response to TLR2 signalling through zymosan being less known.

Methods:

Here, we investigated the effects of zymosan, a TLR2 agonist and the potent and specific LRRK2 kinase inhibitor MLi-2 on gene expression in microglia from LRRK2-WT and LRRK2 p.G2019S knock-in mice by RNA-Sequencing analysis.

Results:

We observed both overlapping and distinct zymosan and MLi-2 mediated gene expression profiles in microglia. At least two candidate Genome-Wide Association (GWAS) hits for PD, CathepsinB (Ctsb) and Glycoprotein-nmb (Gpnmb), were notably downregulated by zymosan treatment. Genes involved in inflammatory response and nervous system development were up and downregulated respectively with zymosan treatment while MLi-2 treatment particularly exhibited upregulated genes for ion transmembrane transport regulation. Furthermore, we observed the top twenty most significantly differentially expressed genes in LRRK2 p.G2019S microglia show enriched biological processes in iron transport and response to oxidative stress.

Discussion:

Overall, these results suggest that microglial LRRK2 may contribute to PD pathogenesis through altered inflammatory pathways. Our findings should encourage future investigations of these putative avenues in the context of PD pathogenesis.

Keywords: LRRK2, TLR2, G2019S knock-in, zymosan, MLi.2, RNA-Seq

1. Introduction

The etiopathology of PD is multifactorial with a complex interplay of genes and environmental triggers1,2. Over the past decades, research has increasingly provided evidence that links neuroinflammation to neurodegeneration in PD. For example, microglia positive for human leukocyte antigen D (HLA-DR) have been identified in the substantia nigra pars compacta of PD patients3. Furthermore, there is an increase in inflammatory biomarkers including tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of PD patients4,5. Similarly, increased IL-1β, IL-6 and gamma delta+ T cells, implicated in inflammation, occurs in blood and brain of PD patients6,7, supporting the potential involvement of immunological events in neurodegeneration.

Mutations in the LRRK2 gene cause autosomal dominant disease with clinical features that are indistinguishable from sporadic PD. The majority of the well characterized pathogenic mutations in LRRK2 are found in the two active catalytic domains (GTPase and kinase) of the encoded large multidomain protein. The common LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation is located within the kinase domain and increases LRRK2 kinase activity8. LRRK2 protein is expressed within the brain and in peripheral tissues with notably high expression in microglia and macrophages9. High expression of dominant PD genes within microglia and/or macrophages suggests that inflammation is relevant for PD development. Knockdown, knockout or pharmacological inhibition of LRRK2 functions results in a decrease in inflammatory responses10,11, further highlighting a potential role of LRRK2 in immune function12. Based on these observations, LRRK2 has been identified as potential therapeutic target for anti-inflammation strategies in PD13

Inflammatory pathways are typically organized where cell surface receptors respond to external signals to trigger intracellular signalling events that result in alterations in gene expression. Prior work has shown that LRRK2 is responsive to extracellular signalling including TLR414. Here, we have investigated the effects of the TLR2 agonist zymosan on gene expression in microglia from LRRK2 p.G2019S knock-in mice by RNA-Seq analysis. We demonstrate that zymosan triggered significant upregulation in LRRK2 phosphorylation which remained significantly inhibited with MLi-2 treatment. We also show that the two genotypes, wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2, and two treatments, zymosan and MLi-2, induced overlapping as well as distinct effects on gene expression profile of microglial cells. Zymosan consistently displayed a stronger effect on gene expression as compared to MLi-2 treatment and G2019S-LRRK2 genotype.

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Animals and primary microglia cultures and treatment

Homozygous LRRK2 G2019S knock-in mice15,16 and C67Bl/6J-wild-type mice were housed at NIH, and all animal procedures were carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines provided by the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of NIH as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the US National Institute on Aging (Approval number: 463-LNG-2018).

Primary mixed glial cultures were established from the brains of wild-type or from knock-in mice harbouring G2019S-LRRK2 mutation at postnatal days 1-2 (P1-2). After approximately 10 days, primary microglia were shaken from mixed glial cultures as described in Russo et al15. Purity of the obtained culture was verified using double immunofluorescence method by staining the culture with rabbit anti-Iba1 (Abcam #ab5076) for microglia, rabbit anti-Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) for astrocytes (Dako Omnis #GA524) and anti- 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Cell Signaling #4083). The primary microglial yield was approximately 5 x 105 cells/flask with minimal astrocyte contamination. For immunoblotting, microglia were seeded and treated with pro-inflammatory agents for 4 hours and 24 hours. For RNA-Seq, cells were seeded and treated with pro-inflammatory agents for 24 hours only. For immunoblottting, cells were lysed with the lysis buffer consisting of 10% cell lysis buffer (10x) (Cell Signaling #9803S), 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (100x) (Cell Signaling #5871S) and 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (100x) (Cell Signaling #5870S), centrifuged at 3200g for 5 min, collected and stored at −80°C for future use. For RNA-Seq collection, RNA was extracted from the primary microglia using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen #15596026) as per manufacturer’s protocol.

2.2. Protein assay

Protein levels were measured using the Thermofisher Pierce BSA Standard Pre-Diluted Set as per manufacturer’s instructions using BSA as standard.

2.3. Zymosan and MLi-2 treatment protocol

Zymosan A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sigma #Z4250) and MLi-2 from Merck (Tocris #5756) were used for these experiments as TLR2 inflammatory stimuli and LRRK2 kinase inhibitor respectively. For immunoblots, primary microglia from wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 Tg mice were treated with 200μg/ml zymosan and 1μM MLi-2 for 4 hours and 24 hours, and for RNA-Seq, they were treated for 24 hours only.

2.4. Immunoblots and fluorescent blots

Samples were heated to 95°C for 3 minutes in loading buffer NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (4x) (Invitrogen NP0008) with 5% β-Mercaptoethanol then loaded on 4-20% Criterion TGX Precast Midi protein gels (Bio-Rad #5671094). The gels were run in TGS buffer (1x) and transferred using Trans-Blot Turbo Mini 0.2μm Nitrocellulose Transfer Packs (Bio-Rad #1704158) using Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight and β-actin for 1 hour. After the membranes were incubated with the appropriate Fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies, protein bands were visualised using Odyssey CLx (Li-Cor) and quantified using Bio-Rad Lab Image (version 6.1) software.

2.5. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

RNA quality and integrity was measured using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Nano Chip (Agilent) and analysed on 2100 Expert Software. The samples were then stored at −80°C until further use. The RNA-Seq was carried out by Psomagen labs, whole-genome sequencing service providers in USA, through Illumina SBS technology using the Total RNA Ribo-Zero Gold Library Kit.

2.6. Analysing RNA-Seq data

RNA-Seq reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using STAR17 and expression counts per transcript was quantified using eXpress18 followed by using DESEQ219 to normalise data. Gene expression data was loaded into MATLAB version R2019b to identify up- and downregulated genes in different treatment and genotype groups through differential gene expression analysis. Subsequently, functional enrichment analysis tools FunRich version 3.1.3 and Hippie version 2.2 were used to perform functional enrichment and interaction network analysis on the identified up- and downregulated genes in different treatment groups, mapping genes

2.7. Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare the difference between the means of three or more treated and untreated independent groups. Unpaired two-tailed student’s t-tests were used to compare the difference between the means of any two normally distributed groups e.g. when determining the difference between non-stimulated cells and cells stimulated with zymosan. The statistical tests used for each data set are mentioned where appropriate in the legends of every experimental figure. All data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 5, R Studio version 1.3.1093, MATLAB version R2019b. All quantitative data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and represent in most cases at least three independent set of experiments. The exact number of experiments with internal replicates is mentioned in the legends of every experimental figure. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Zymosan induces phosphorylation of LRRK2 in microglia

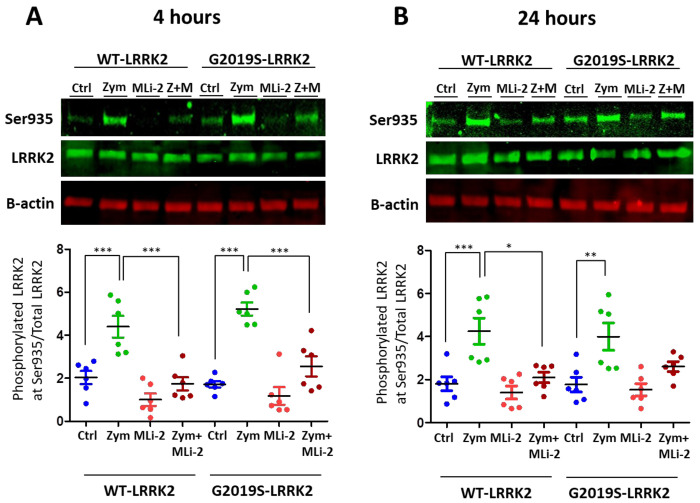

LRRK2 is phosphorylated at a series of residues between the ankyrin and leucine-rich repeat domains, including Serine93520. Phosphorylation of LRRK2 at S935 is controlled by other kinases, notably casein kinase 1α21, but is also responsive to inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity22. We therefore used pS935 as a proxy for LRRK2 activation. A significant upregulation of LRRK2 phosphorylation at Ser935 was observed with zymosan treatment at 4 hours and 24 hours (Figure 1) in wild-type or G2019S knock-in cells. Co-treatment of cells with zymosan and MLi-2 resulted in a significant decrease in pS935-LRRK2 levels at 4 hours in both genotypes and at 24 hours in wild type cells.

Figure 1:

LRRK2 phosphorylation evoked by zymosan is inhibited with MLi-2 treatment in wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. Wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 were treated with 1μM MLi-2 and 200μg/ml zymosan for 4h and 24h. Fluorescent immunoblots and corresponding quantifications are shown for (A) 4h and (B) 24h. Blots were probed with LRRK2 phosphorylation antibody pSer935 and total LRRK2. Controls contain media only. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. of 2 independent experiments (with internal triplicates in each experiment). * and ** and *** signify p<0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. Colours for graphs indicate: Blue: Control, Green: zymosan, Red: MLi-2, Dark red: zymosan+MLi2 treatments. Ctrl: Control, Zym/Z: zymosan, M: MLi-2

3.2. Differential gene expression between wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 with zymosan and MLi-2

Having established that zymosan treatment results in an increase in pS935 LRRK2, we next performed RNA-Seq to evaluate the effects of LRRK2 modulation on inflammatory signalling in two genotype groups (WT and G2019S) and four treatments (control, MLi-2, zymosan and zymosan plus MLi-2). Mean vs variance plots for gene expression after variance stabilizing transformation indicate that variance was consistent across gene expression levels in both genotypes (Supplementary Figure S1A,B).

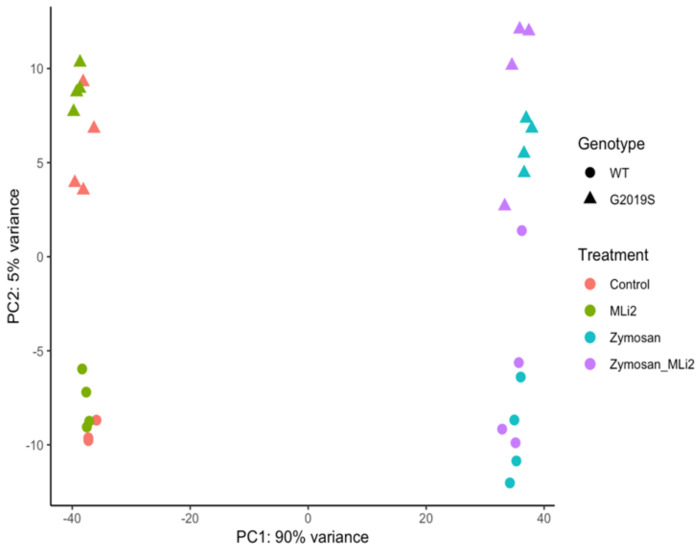

We next examined the first two principal components of the overall gene expression patterns against genotype and treatment groups. PC1, which explains ~90% of the variance, aligns with zymosan treatment, with or without the addition of MLi-2, while PC2, which captures ~ 5% of the variance, appears to be largely explained by genotype (Figure 2). Consistent with this overall view of the data, clustering of overall gene expression by Euclidean distance show a clear separation between zymosan treated samples and samples without zymosan, followed by separation by genotype and finally MLi-2 treatment (Figure 3A). Two additional heatmaps (Figure 3B) reveal the top twenty differentially expressed genes with the highest mean expression across all genotypes and treatments.

Figure 2:

RNA-Seq profiling showed by first two principal components of wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia after zymosan and MLi-2 stimulation. First two principal components, PC1 and PC2, of all samples used in the study. Data contains two biological variables, treatment with zymosan and MLi-2 and genotype (wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2). Note that samples separate largely by treatment and to a lesser extent by genotype.

Figure 3:

Heatmaps and clustering analysis of RNA-Seq profiling of wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia after zymosan and MLi-2 stimulation, Volcano plots highlighting significantly differentially expressed genes with zymosan treatment in wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 genotypes and Protein interaction maps. (A) Hierarchical clustering and heatmap of all samples used in this study. Colours in the heatmap represent the Euclidean distance between samples in a pairwise manner, scaled as shown on the upper right yellow-blue scale. Above the heatmap is a colour representation of the model variables, which included two biological variables, treatments with zymosan and MLi-2 and genotype (wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2). Note that samples separate largely by treatment and to a lesser extent by genotype. (B) Heatmaps for the top twenty most statistically significant genes with the highest mean expression across all samples. Each gene on the right side of each heatmap is coloured by Z (normalized standard deviations from the mean) for expression relative to the overall mean expression for that gene and samples are listed below each heatmap. (C) shows significantly differentiated genes with zymosan treatment in G2019S-LRRK2 and (D) shows genes in wild-type. Each point represents a significantly differentiated gene. Dark blue colour depicts genes which passed the thresholds for 2-Log Fold Change with upper right hand quadrant showing upregulated and upper left hand quadrant showing downregulated genes. The top twenty genes with the highest mean expression across all samples shown in (B) are shown in boxes in these volcano plots. (E) Protein interaction maps generated with Hippie software showing the interaction of Ctsb protein (blue) and Gpnmb protein (green) with other interacting proteins. Ctrl: Control, Zymo: Zymosan

We next examined gene expression between treatment groups. Volcano plots show significantly differentially expressed genes with zymosan treatments in both wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 genotypes (Figures 3C and 3D). There were abundant differences driven by zymosan treatment including Fth1 and lysosomal genes, which we have previously shown to be responsive to LPS-induced inflammation in microglia23. We also note that at least two candidate GWAS hits for PD, namely Ctsb) and Gpnmb, are downregulated by Zymosan treatment, irrespective of genotypes.

3.3. Functional enrichment analysis in wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 with zymosan and MLi-2

Two protein interaction maps generated with Hippie software show the interaction of Ctsb and Gpnmb proteins with other interacting proteins. Ctsb and Gpnmb from the list of top twenty genes (Figure 3E) are also GWAS hits for PD24 hence it is interesting to see their interacting proteins in the context of PD.

Ontological analysis of significant differentially expressed genes was performed using FunRich software (version 3.1.3). Figure 4 shows biological processes (A-B) and cellular components (C-D) significantly enriched in zymosan-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. The most enriched GO terms for biological processes in upregulated genes were inflammatory response and nervous system development in downregulated genes. The most enriched GO terms for cellular components were plasma membrane for upregulated genes and glutamatergic synapse for downregulated genes.

Figure 4:

GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in zymosan-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. GO (A-B) biological process and (C-D) cellular component enrichment analyses of (A,C) upregulated proteins and (B,D) downregulated proteins in zymosan-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglial cells were performed using FunRich functional enrichment analysis tool. Significantly enriched GO terms are shown with Benjamini-Hochberg and Bonferroni-corrected p-values. Statistical significance was taken at p < 0.05

Furthermore, Figure 5 show (A-B) biological processes and (C) cellular components significantly enriched in MLi-2 treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. The most enriched GO terms for biological processes in upregulated genes were regulation of ion transmembrane transport and positive regulation of apoptotic process in downregulated genes. The most enriched GO terms for cellular components were plasma membrane for downregulated genes and no significantly enriched cellular components terms for upregulated genes (Supplementary Table S1). Notably, Figure 6 shows (A) biological processes and (C) cellular components significantly enriched for top twenty most significantly differentially expressed genes in G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. The most enriched GO terms for biological processes in upregulated genes were iron ion transport and response to oxidative stress and extracellular space for the most enriched GO terms for cellular components.

Figure 5:

GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in MLi2-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglia. GO (A-B) biological process and (C) cellular component enrichment analyses of (A) upregulated proteins and (B,C) downregulated proteins in MLi2-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglial cells were performed using FunRich functional enrichment analysis tool. There were no significantly enriched GO terms with upregulated proteins in MLi2-treated wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 microglial cells in my data, hence no data for that is shown. Significantly enriched GO terms are shown with Benjamini-Hochberg and Bonferroni-corrected p-values. Statistical significance was taken at p < 0.05

Figure 6:

GO enrichment analysis of the top twenty most statistically significant genes with the highest mean expression across all treatments and genotype. GO (A) biological process and (B) cellular component enrichment analyses of top twenty most statistically significant differentially expressed genes across all samples (from Figure 5) were performed using FunRich functional enrichment analysis toolSignificantly enriched GO terms are shown with Benjamini-Hochberg and Bonferroni-corrected p-values. Statistical significance was taken at p < 0.05

4. Discussion:

Microglia are resident innate immune cells of the CNS, contributing neuroprotective characteristics during acute immune responses but are also implicated as mediators of cell loss in neurodegenerative disorders after chronic activation. Activated microglia have been found in SNpc of PD patients25 and are also implicated in causing damage to dopaminergic neurons26. The active role of microglia in neuroinflammation is also reviewed in a study by Perry et al27. Upon activation by inflammatory stimuli, microglia switch from resting to activated state, releasing pro-inflammatory and reactive oxygen species to mediate an inflammatory response28. LRRK2 is highly expressed in microglia9, indicating a possible role for LRRK2 and microglia in contributing to PD pathogenesis through altered inflammatory signalling. The inflammatory stimulus LPS is widely used to trigger microglial activation as previously carried out14, and are used to analyse the transcriptomic profile of primary microglial cells by various studies29,30. To our knowledge, transcriptomic data using zymosan as an inflammatory stimulus in the context of LRRK2 has not been investigated to date.

To dissect novel LRRK2-related biological processes in microglia, we performed RNA-Seq analysis of wild-type and G2019S-LRRK2 cells under basal conditions, or after stimulation with zymosan and in the presence of the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor, MLi-2. We observed various overlapping and individual effects on gene expression and induction of biological processes. Our data has shown zymosan to have a stronger effect on gene expression as compared to MLi-2 treatment or genotype. This was confirmed with first principle component of the overall gene expression profile which separated zymosan from MLi-2 and basal treatment groups, whereas genotype had a more subtle effect on overall gene expression. The results are unsurprising given that zymosan is a strong stimulator of immune signalling similar to LPS with LRRK2 likely playing a modulatory role through altered lysosomal responses23.

Enrichment analyses showed that some of the most enriched GO terms for biological processes in zymosan-treated wild-type microglial cells were inflammatory response, innate immune response and cytokine-mediated signalling pathways (Figure 4A). However, these GO terms were not significantly enriched in G2019S genotype, which is suggestive of the potential involvement of G2019S-LRRK2 (hyperkinetic) in inflammatory responses. Pathways significantly enriched with zymosan treatment in G2019S genotype involved adrenomedullin receptor signalling pathway, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) biosynthetic process, receptor guanylyl cyclase signalling pathway and neuropeptide signalling pathway which were not observed in wild-type cells (Figure 4A). Therefore, it may be important to investigate these pathways in the context of PD pathogenesis. Adrenomedullin has been recently discussed to be an important participant in neurological diseases and is seen to exhibit neuroprotective effect against brain insults31. Similarly, guanylyl cyclase-cGMP signalling and the neuropeptides and neurotransmitters are also known to play a role in PD pathogenesis32,33. GO enriched terms also indicate zymosan to be a positive regulator of ERK1 and ERK2 signalling cascade and apoptotic processes. ERK kinases belong to the MAPK superfamily of kinases which are known to be implicated in PD34. The most significantly enriched terms for biological processes for downregulated proteins with zymosan treatment in G2019S genotype cells include nervous system development, regulation of ion transmembrane transport and modulation of chemical synaptic transmission indicating these processes to perhaps be negatively affected in PD.

In terms of cellular processes, the most enriched terms for zymosan treatment in wild-type and G2019S genotype include plasma membrane, extracellular space and glutamatergic synapse. MLi-2 on the other hand seemed to have a more subtle effect on expressed genes and enriched GO terms. Interestingly, for enriched biological processes in G2019S, upregulated genes in MLi-2 seemed to only significantly enrich processes involved in myelination. However, the underlying mechanisms of the inflammatory effects and role of microglia is yet to be fully understood in the context of PD.

Furthermore, in basal G2019S condition, downregulated proteins were significantly enriched for chemotactic pathways such as natural killer cell, lymphocyte and eosinophil chemotaxis. This is suggestive of suppressed chemotactic abilities in PD pathogenesis and indeed a recent study has found lymphocyte chemotaxis to be impaired in PD patients35. Furthermore, it also suggests that microglia expressing G2019S have an inability to become recruited to areas of damage within the PD brain parenchyma. A similar microglial response is linked to the AD risk gene TREM236. Defence response to virus was also significantly enriched for downregulated proteins in G2019S genotype which is confirmative of impaired response to virus as one of the key contributors in PD pathogenesis. Previous studies have shown that systemic and local inflammatory responses to viruses have potential involvement in neuronal damage, even in the absence of neuronal cell death. Viruses are seen to evoke CNS inflammation either by entering the brain or by crossing a damaged BBB or along the peripheral nerves or by activating the peripheral innate and adaptive immune responses37,38. Cellular components most significantly enriched in upregulated proteins in G2019S genotype also consist of plasma membrane, myelin sheath and internode and paranode regions of axon, rendering investigating all these biological processes and cellular components important in the context of PD39,40.

The top twenty genes which showed the highest mean expression across all genotype and treatment conditions also revealed some intriguing aspects to the results. First, two of the twenty genes, Gpnmb and Ctsb, were reported as genetic risk loci for PD in a recent GWAS study24. Elevated expression of Gpnmb is associated with increased PD risk41 and through its interaction with alpha-synuclein, it may also confer increased disease risk42. It is noteworthy that CathepsinD (ctsd) gene is mutated in human neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 43,44. Interestingly, LRRK2 G2019S leads to suppression of lysosomal proteolytic activity in macropahges and it regulates the abundance of multiple lysosomal proteins45. Therefore, research on Ctsb, Ctsd and Gpnmb in relation to LRRK2 and their interacting proteins should be expanded in order to further elucidate the molecular underpinnings of PD. Enriched biological processes for the top twenty genes show most significantly enriched terms to be iron ion transport and response to oxidative stress and enriched cellular components show extracellular space and lysosomes to be most significantly enriched (Figure 6). These are indeed important biological processes and cellular components implicated in PD.

Summary/Conclusion:

With this data, our study is the first to report the identification of differential gene expression and dissection of novel biological pathways in response to zymosan and LRRK2 kinase inhibition with MLi-2 in G2019S-LRRK2 KI primary microglia cells. The data presented in this paper raise several interesting points and opens up new pathways of PD research that would be suitable for further investigation. In this study, we assessed LRRK2 activation via phosphorylation of Ser935 – an indirect measure, mediated by an upstream kinase. In future work, it will be important to assess direct measures of LRRK2 kinase activity such as LRRK2 Ser1292 phosphorylation 46, and phosphorylation of Rab proteins such as Rab10, Rab12 or Rab8a. One interesting future research direction could be to utilize human-derived cells with native LRRK2 expression. It would be necessary to understand whether human primary cells have the same phenotype as the mouse equivalents, or whether they diverge in phenotype. With the increasing use of stem cell derived human cells to model disease, assessing zymosan induced changes in expression in pluripotent stem cell derived macrophages and microglia with and without G2019S-LRRK2 mutations will be insightful for a deeper, and more human relevant, analysis. As noted above, the various enriched biological pathways discussed in this paper should be highlighted and prioritised for investigation in the context of PD pathogenesis – especially the regulation of genes implicated by genome wide association studies for PD that are linked to lysosomal function. Finally, it is hoped that the findings from the research conducted for this paper will help advance the understanding of PD pathogenesis and drug development towards new therapies for the millions of people world-wide living with PD47.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Standard deviation to visualise the variance of the data. The plots show the standard deviations of the transformed data, across all samples, against the mean, using the shifted logarithm transformation, the regularized log transformation and the variance stabilizing transformation. Each point represents a differentially expressed gene and (A) shows variance between this differential expression between genes in G2019S-LRRK2 and (B) shows variance in wild-type.

Supplementary Table S1. List of RNA Seq transcripts up and down regulated in WT and G2019S mice with Zymosan and MLi2 treatment.

Acknowledgements:

RB is funded by the Reta Lila Weston Trust for Neurological Studies. IN was a recipient of the Yule Bogue Fellowship (UCL) to carry out the experiments at NIA/NIH. This work was supported in part by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and the National Institutes of Health grants NS110188 and AG077269 to Adamantios Mamais. Anna Mallach was supported by BBSRC London Interdisciplinary Biosciences Consortium (LIDo; BB/M009513/1). CB is supported by Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK-RF2019B-005) and Multiple System Atrophy Trust.

References:

- 1.Johnson M. E., Stecher B., Labrie V., Brundin L. & Brundin P. Triggers, Facilitators, and Aggravators: Redefining Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci 42, 4–13, doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.09.007 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherian A. & Divya K. P. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Belg 120, 1297–1305, doi: 10.1007/s13760-020-01473-5 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGeer P. L., Itagaki S., Boyes B. E. & McGeer E. G. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38, 1285–1291, doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1285 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mogi M. et al. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha are elevated in the brain from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci Lett 180, 147–150, doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90508-8 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogi M. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) increases both in the brain and in the cerebrospinal fluid from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci Lett 165, 208–210, doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90746-3 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiszer U. et al. gamma delta+ T cells are increased in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 121, 39–45, doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90154-6 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum-Degen D. et al. Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s and de novo Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett 202, 17–20, doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12192-7 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren C. et al. G2019S Variation in LRRK2: An Ideal Model for the Study of Parkinson’s Disease? Front Hum Neurosci 13, 306, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00306 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thevenet J., Pescini Gobert R., Hooft van Huijsduijnen R., Wiessner C. & Sagot Y. J. Regulation of LRRK2 expression points to a functional role in human monocyte maturation. PLoS One 6, e21519, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021519 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moehle M. S. et al. LRRK2 inhibition attenuates microglial inflammatory responses. J Neurosci 32, 1602–1611, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5601-11.2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daher J. P., Volpicelli-Daley L. A., Blackburn J. P., Moehle M. S. & West A. B. Abrogation of alpha-synuclein-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration in LRRK2-deficient rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 9289–9294, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403215111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langston R. G. et al. Association of a common genetic variant with Parkinson’s disease is mediated by microglia. Sci Transl Med 14, eabp8869, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abp8869 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo I., Bubacco L. & Greggio E. LRRK2 as a target for modulating immune system responses. Neurobiol Dis 169, 105724, doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105724 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazish I. et al. Abrogation of LRRK2 dependent Rab10 phosphorylation with TLR4 activation and alterations in evoked cytokine release in immune cells. Neurochem Int 147, 105070, doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105070 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russo I. et al. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 controls protein kinase A activation state through phosphodiesterase 4. J Neuroinflammation 15, 297, doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1337-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pellegrini L. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals co-ordinated alterations in protein synthesis and degradation pathways in LRRK2 knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet 27, 3257–3271, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy232 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobin A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts A. & Pachter L. Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat Methods 10, 71–73, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2251 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love M. I., Huber W. & Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550, doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchand A., Drouyer M., Sarchione A., Chartier-Harlin M. C. & Taymans J. M. LRRK2 Phosphorylation, More Than an Epiphenomenon. Front Neurosci 14, 527, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00527 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chia R. et al. Phosphorylation of LRRK2 by casein kinase 1alpha regulates trans-Golgi clustering via differential interaction with ARHGEF7. Nat Commun 5, 5827, doi: 10.1038/ncomms6827 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols R. J. et al. 14-3-3 binding to LRRK2 is disrupted by multiple Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations and regulates cytoplasmic localization. Biochem J 430, 393–404, doi: 10.1042/BJ20100483 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mamais A. et al. Mutations in LRRK2 linked to Parkinson disease sequester Rab8a to damaged lysosomes and regulate transferrin-mediated iron uptake in microglia. PLoS Biol 19, e3001480, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001480 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nalls M. A. et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol 18, 1091–1102, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30320-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilms H. et al. Activation of microglia by human neuromelanin is NF-kappaB dependent and involves p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: implications for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J 17, 500–502, doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0314fje (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y., Le W. D. & Appel S. H. Role of Fcgamma receptors in nigral cell injury induced by Parkinson disease immunoglobulin injection into mouse substantia nigra. Exp Neurol 176, 322–327, doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7946 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry V. H. & Holmes C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 10, 217–224, doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.38 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garden G. A. & Moller T. Microglia biology in health and disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 1, 127–137, doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9015-5 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo I. et al. Transcriptome analysis of LRRK2 knock-out microglia cells reveals alterations of inflammatory- and oxidative stress-related pathways upon treatment with alpha-synuclein fibrils. Neurobiol Dis 129, 67–78, doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.05.012 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulido-Salgado M., Vidal-Taboada J. M., Barriga G. G., Sola C. & Saura J. RNA-Seq transcriptomic profiling of primary murine microglia treated with LPS or LPS + IFNgamma. Sci Rep 8, 16096, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34412-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li F. J., Zheng S. R. & Wang D. M. Adrenomedullin: an important participant in neurological diseases. Neural Regen Res 15, 1199–1207, doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.272567 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West A. R. & Tseng K. Y. Nitric Oxide-Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase-Cyclic GMP Signaling in the Striatum: New Targets for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease? Front Syst Neurosci 5, 55, doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00055 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li C. et al. Roles of Neuropeptide Y in Neurodegenerative and Neuroimmune Diseases. Front Neurosci 13, 869, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00869 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dzamko N., Zhou J., Huang Y. & Halliday G. M. Parkinson’s disease-implicated kinases in the brain; insights into disease pathogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci 7, 57, doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00057 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perner C. et al. Plasma VCAM1 levels correlate with disease severity in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 16, 94, doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1482-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Reitboeck P. et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell derived microglia-like cellsharbouring TREM2 missense mutations show specific deficits in phagocytosis. Cell Rep 24(9), 2300. doi: 10.1016/jcellrep.2018.07.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van den Pol A. N. Viral infections in the developing and mature brain. Trends Neurosci 29, 398–406, doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.002 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang T. et al. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med 10, 1366–1373, doi: 10.1038/nm1140 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herbst S. et al. LRRK2 activation controls the repair of damaged endomembranes in macrophages. EMBO J 39, e104494, doi: 10.15252/embj.2020104494 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weindel C. G. et al. LRRK2 maintains mitochondrial homeostasis and regulates innate immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Elife 9, doi: 10.7554/eLife.51071 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murthy M. et al. , Increased brain expression of GPNMB is associated with genome-wide significant risk for Parkinson’s disease on chromosome 7p15.3. Neurogenetics, 18 (3), 121. doi: 10.1007/s10048-017-0514-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diaz-Ortiz ME et al. GPNMB confers risk for parkinson’s disease through interaction with alpha-synuclein. Science, 377(6608). ebak0637.doi: 10.1126/science.abk0637.(2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinfeld R. et al. , Cathepsin D deficiency is associated with a human neurodegenerative disorder. Am J Hum Genet 78(6): 988–998. (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siintola E. et al. Cathepsin D deficiency underlies congenital human neuronal ceroid -lipofuscinosis. Brain 129(6)1438. Doi: 10.1093/brain/awhl107 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadavalli N., and Ferguson S.M. LRRK2 negatively regulates the abundance of multiple lysosomal proteins and the G2019S LRRK2 mutation suppresses lysosomal proteolytic activity in macrophages. PNAS, 120(31), e2303789120. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kluss J.H. et al. Detection of endogenous S1292 LRRK2 autophosphorylation in mouse tissue as a readout for kinase activity. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 4, 13, doi: 10.1038/s41531-018-0049-1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexander G. E. Biology of Parkinson’s disease: pathogenesis and pathophysiology of a multisystem neurodegenerative disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 6, 259–280, doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2004.6.3/galexander (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Standard deviation to visualise the variance of the data. The plots show the standard deviations of the transformed data, across all samples, against the mean, using the shifted logarithm transformation, the regularized log transformation and the variance stabilizing transformation. Each point represents a differentially expressed gene and (A) shows variance between this differential expression between genes in G2019S-LRRK2 and (B) shows variance in wild-type.

Supplementary Table S1. List of RNA Seq transcripts up and down regulated in WT and G2019S mice with Zymosan and MLi2 treatment.