Abstract

Objective:

Suicide is a leading cause of death among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) young people aged 10-19 years in the United States, but data collection and reporting in this population are lacking. We examined results of an oversample project in New Mexico to determine the association between resiliency factors and suicide-related behaviors among AI/AN middle school students.

Methods:

We conducted analyses using data from the 2019 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey for students in grades 6 through 8. An oversampling method was used to increase the sample size of AI/AN students. We used logistic regression to determine the association between resiliency factors and suicide indicators among AI/AN students, stratified by sex.

Results:

Among female AI/AN students, community support had the strongest protective effect against having seriously thought about suicide (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.14-0.38), while family support was significantly associated with the lowest odds of having made a suicide plan (aOR = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.28) and having attempted suicide (aOR = 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.34) (P < .001 for all). Among male AI/AN students, school support had the strongest protective effect against all 3 outcomes: seriously thought about suicide (aOR = 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19-0.62; P < .001), having made a suicide plan (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.39; P < .001), and having attempted suicide (aOR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.12-0.65; P = .003).

Conclusions:

Oversampling AI/AN young people can help accurately quantify and understand health risk behaviors and strengths of this population, leading to improved health and wellness. Family, community, and school-based support should be considered in interventions geared toward suicide prevention among AI/AN young people.

Keywords: adolescent health, risk/risk behaviors, American Indian or Alaska Native, research methods, prevention

In discussing health disparities, it is essential to address the extent to which lack of data contributes to the inability to accurately quantify health behaviors in small racial and ethnic groups, such as American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) people.1 -3 Often, this racial and ethnic group is underrepresented in large datasets with sample sizes that are perceived to be too small to produce reliable data results and/or findings that are considered meaningful according to Western standards.1 -3 Often, the AI/AN category is suppressed for privacy protection or combined with other racial and ethnic minority groups to increase sample size. 4 Suppressing these data can result in either missing AI/AN data or unrepresentative data, with both instances contributing to an inability to accurately quantify, understand, and address health issues among AI/AN populations through analytic studies. 1

Oversampling has been found to be an effective strategy for improving the accuracy and availability of AI/AN health-related data collected through large surveillance systems.1,3,5 In an effort to produce data that are both robust and representative of AI/AN populations, the Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center (AASTEC), in partnership with state and academic entities, launched an AI/AN oversample project in 2011 as a component of the New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (NMYRRS). The NMYRRS is a state-level version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), the largest public health surveillance system in the United States, which monitors health behaviors, conditions, and experiences of students in grades 6-12. 6 Through the AI/AN oversample project, the number of AI/AN students participating in the NMYRRS has increased. This increase in AI/AN students allows for both complex and granular, school-level analysis to be performed for AI/AN students independently of other racial and ethnic groups, resulting in reliable and pragmatic results that can be used to inform interventions.

High-quality data are essential for all populations and subgroups but especially as the data pertain to young people’s health, because adolescence is a pivotal time in which lifelong health behaviors are often established.7,8 Accurate identification of areas of concern and resilience is key to establishing interventions to either curb risky health behaviors or build on sources of strength that can then be carried forward into adulthood.8 -10 Through the NMYRRS AI/AN oversample project, health behaviors of AI/AN young people in New Mexico can reliably be characterized for students in grades 6-12. The robust NMYRRS AI/AN student sample obtained through oversampling methods allows for in-depth investigation into areas of concern for this population such as suicide, which is reported in the United States at a disproportionately higher rate among AI/AN people than among all other racial and ethnic groups and is the second leading cause of death for AI/AN young people aged 10-19 years.11 -13

In the past 2 decades, suicide attempt rates have been consistently higher in New Mexico than in the United States overall. 14 In New Mexico, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 23% from 2010 to 2020, and the state ranked fourth in the nation for suicide in 2020.15,16 The New Mexico Department of Health reported that one-quarter of all suicide deaths in the state during 2019-2020 were among children and adolescents aged <18 years. 15 As of 2020, suicide was the leading cause of death in New Mexico among children and adolescents aged 10-14 years and the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults aged 15-19 years. 17 Suicide rates in New Mexico are highest among AI/AN people, and suicide rates increased in this group by 58% from 2011 to 2020. 16 Considering that the strongest risk factor for death by suicide is a prior suicide attempt, identifying protective factors that decrease the odds of suicide-related behaviors and suicide attempt early in life is key in establishing effective suicide interventions that benefit both AI/AN young people and adults.18 -20 Currently, a lack of understanding of suicide risk and prevention exists among middle school students because most of the literature focuses only on high school students. Incorporating protective factors and strength-based approaches that promote the resilience of AI/AN communities is known to be effective in mitigating AI/AN suicide incidence.10,21 -23 If the relationship between protective factors and suicide incidence, which is well-established among AI/AN adults and older teens, holds true for AI/AN students in middle school, such a finding could provide clear direction for suicide prevention programs to provide support and interventions even earlier in life.

Previous studies have found that resiliency factors are protective against suicide attempt among AI/AN high school students in New Mexico and that the strength of this association differs by location of school and gender.24,25 Whether these findings hold true for AI/AN middle school students in New Mexico is unknown. Our study had 2 objectives: (1) provide information on the background, process, and successes of the AASTEC NMYRRS AI/AN oversample project and (2) demonstrate the benefit of having AI/AN oversample data by examining the association between resiliency factors and suicide-related behaviors as reported among AI/AN middle school students.

Methods

Data Source

We used data from the 2019 NMYRRS to complete this analysis. The NMYRRS is a voluntary, anonymous survey administered in New Mexico schools biennially among students in grades 6-12 as part of the CDC YRBSS.26,27 The study team obtained parental permission prior to survey administration via a passive consent process and deployed the 2019 NMYRRS as a self-administered questionnaire that students completed in school during a single class period and recorded their responses via scantron booklet. The NMYRRS contains questions that pertain to adolescent health and risk behaviors, along with questions adapted from the California Healthy Kids Survey that measure sources of resiliency in various domains of students’ lives. 28

The New Mexico Department of Health, University of New Mexico, the New Mexico Public Education Department, and AASTEC collected the 2019 NMYRRS data from August through December 2019. The survey epidemiologist weighted these data to adjust for nonresponse and distribution of students by demographic characteristics. 13 Our analysis focused on data from the 2019 NMYRRS for middle school students only (ie, students in grades 6-8). Students in the middle school sample ranged in age from 10 to 16 years. The Southwest Tribal Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Sampling Method and AI/AN Oversample Protocol

Schools in New Mexico are chosen to administer the NMYRRS based on a modified CDC YRBSS sampling protocol, which involves a stratified, 2-stage cluster sample design where the probability of a school being chosen to administer the survey is proportional to the size of the school, based on student enrollment.18,25 Within each school chosen to administer the survey, only students enrolled in certain classes (chosen at random) complete the survey.18,25 AASTEC draws an additional sample to obtain robust data for AI/AN students in which certain schools that enroll a high proportion of AI/AN students are oversampled at the classroom level, meaning that every class in schools that are included in the AI/AN oversample administers the survey.

The oversample protocol used in 2019 was developed and refined during several survey cycles. Starting in 2007, a test sample of 3 high schools that served exclusively AI/AN students on Tribal lands was invited to participate. AASTEC developed its protocol for school recruitment, teacher incentives, and data dissemination with the approval of the Southwest Tribal Institutional Review Board and its project partners. The response rate among the first 3 schools in 2007 was 70%. Based on this successful pilot, 23 additional middle schools and high schools with at least 75% AI/AN student enrollment were included in the subsequent sample in 2009. Thereafter, and in consultation with Tribal leadership, all middle schools and high schools located within or adjacent to the 27 Tribal communities served by AASTEC were invited to participate, regardless of the percentage of AI/AN student enrollment. In 2019, 54 schools were invited to administer the NMYRRS as part of the AI/AN oversample; 44 of these schools (18 high schools, 26 middle schools) opted to participate, and the AI/AN oversample had an overall response rate of 78%. Statewide, 2843 AI/AN high school and middle school students were administered the 2019 NMYRRS under the standard sampling framework. An additional 3193 AI/AN high school and middle school students completed the 2019 NMYRRS as part of the AI/AN oversample project, resulting in a total of 6036 AI/AN high school and middle school students represented in the 2019 NMYRRS data (unpublished data, 2007-2019 AASTEC NMYRRS AI/AN oversample project). We analyzed data for the 3018 AI/AN middle school students in grades 6-8 who completed the 2019 NMYRRS, 1548 of whom were administered the survey under the standard sampling framework and 1470 of whom completed the survey as part of the AI/AN oversample project.

Measures

We categorized students as AI/AN if they indicated “American Indian or Alaska Native” in response to the survey question, “Which one of these groups best describes you?” If the response to this question was missing, we considered students to be AI/AN if they answered “no” to the question “Are you Hispanic or Latino” AND indicated “American Indian or Alaska Native” only to the question “What is your race?” (This question allowed for multiple responses.)

The middle school NMYRRS instrument includes 3 questions related to suicidality: “Have you ever seriously thought about killing yourself?” “Have you ever made a plan about how you would kill yourself?” and “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” These questions measure suicide-related behaviors across students’ lifetime and allow for a binary yes/no response.

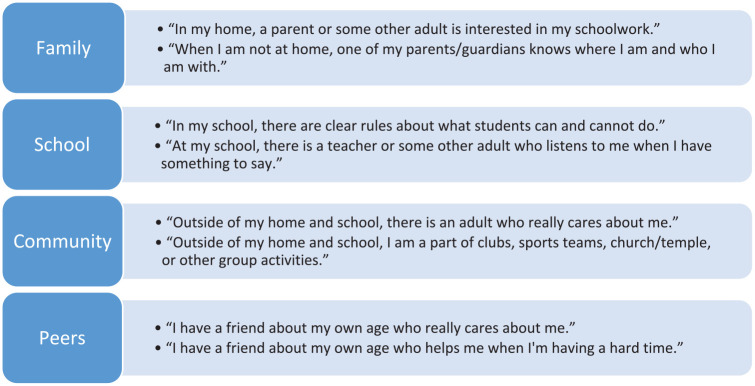

Resiliency is measured via 8 indicators related to relationships and support in 4 domains of students’ lives: family, school, community, and peers (Figure). Within each domain, 2 statements are provided that allow for a single response on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = not true at all to 4 = very much true. We created composite scores for each domain by totaling the numeric value of the 2 statements. We created a single variable for each domain based on the composite score with 3 categories: 1-4 = low level of support, 5-7 = moderate level of support, and 8 = high level of support.

Figure.

Resiliency measures, by domain, included in the 2019 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (NMYRRS) Middle School Survey Instrument. Each statement within the 4 domains of support allows for a single response on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 4 (very much true). The numeric value of the 2 statements was combined to form a single composite score ranging from 1 to 8 for each domain. The composite score was quantified into a single indicator of support within each domain by 3 levels: 1-4 (low level of support), 5-7 (moderate level of support), and 8 (high level of support). Data source: 2019 NMYRRS. 27

Statistical Analysis

The survey epidemiologist weighted data to account for nonresponse bias and differences in distribution of students by sex, grade, and race and ethnicity. 29 We reported prevalence estimates and 95% CIs for demographic characteristics, suicide indicators, and resiliency factors for AI/AN students. We also calculated prevalence estimates and 95% CIs for AI/AN students stratified by sex.

We constructed logistic regression models for male and female AI/AN students separately to determine the association between resiliency factors and suicide indicators. The primary predictor in each model was the presence of high level of support (a composite score of 8) for each of the 4 resiliency domains, and the reference category was the lowest level of support (a composite score of 1-4). We excluded moderate level of support from analysis to examine the greatest extent to which resiliency factors may be protective against suicide-related outcomes. By using high level of support in each of the 4 resiliency domains (family, school, community, and peer support) as the primary predictor, we created separate univariate models to predict the odds of each of the 3 suicide-related outcomes among male and female students. We adjusted models for grade, rural location of school, and location of school in relation to the nearest Tribal lands, all of which have been found to be associated with suicidality among AI/AN young people.24,30,31 We did not include resiliency construct variables in regression models together to avoid overfitting and in an attempt to identify the independent protective effect of each resiliency factor on suicide-related outcomes. We reported adjusted odds ratios (aORs), 95% CIs, and P values for each model. We used the Pearson χ2 test and set significance at α = .05. We conducted all analyses using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

A total of 19 677 students participated in the 2019 middle school NMYRRS, for a response rate of 81.0%; 15.3% (n = 3018) of middle school students identified as AI/AN (Table 1). Among AI/AN students, the average age was 12 years (SD = 1.01), nearly half (47.8%; 95% CI, 45.3%-50.4%) were female, two-thirds (67.6%; 95% CI, 60.9%-73.7%) attended a school in a rural location, 58.0% (95% CI, 51.0%-64.7%) attended a school on or near Tribal lands, and 5.8% (95% CI, 2.6%-12.6%) attended a Bureau of Indian Education school. Almost one-third of AI/AN students (30.5%; 95% CI, 28.3%-32.8%) reported that they had thought about suicide at some point in their life, 18.8% (95% CI, 17.0%-20.7%) reported that they had made a suicide plan, and 15.3% (95% CI, 13.6%-17.2%) reported having attempted suicide (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and key health indicators among American Indian/Alaska Native middle school students (N = 3018), 2019 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (NMYRRS) a

| Variable | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 12 (1.01) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 52.2 (49.6-54.7) |

| Female | 47.8 (45.3-50.4) |

| School located in rural location | 67.6 (60.9-73.7) |

| School located on or near Tribal lands | 58.0 (51.0-64.7) |

| Attends Bureau of Indian Education school | 5.8 (2.6-12.6) |

| Unstable housing, past 30 d | 4.1 (3.0-5.6) |

| Seriously thought about suicide | 30.5 (28.3-32.8) |

| Made a suicide plan | 18.8 (17.0-20.7) |

| Has attempted suicide | 15.3 (13.6-17.2) |

| Family support level b | |

| High | 32.2 (29.6-35.0) |

| Moderate | 57.1 (54.7-59.5) |

| Low | 10.7 (9.1-12.5) |

| School support level b | |

| High | 32.4 (29.5-35.4) |

| Moderate | 55.7 (53.1-58.2) |

| Low | 12.0 (9.4-15.1) |

| Community support level b | |

| High | 27.3 (25.2-29.4) |

| Moderate | 55.2 (52.8-57.5) |

| Low | 17.6 (15.0-20.5) |

| Peer support level b | |

| High | 45.1 (42.6-47.6) |

| Moderate | 36.8 (34.2-39.6) |

| Low | 18.1 (16.4-20.0) |

Data source: 2019 NMYRRS. 28

Created by averaging response values for questions in each support category, yielding a possible range of 1 to 8 for the created construct variable: 1-4 = low level of support, 5-7 = moderate level of support, and 8 = high level of support.

Suicide Indicators and Resiliency Factors Among AI/AN Students

Among AI/AN students, female students reported significantly higher rates across all 3 suicide indicators compared with males (seriously thought about suicide: 42.6% vs 19.4%; made a suicide plan: 27.5% vs 10.7%; attempted suicide: 23.6% vs 7.7%; P < .001 for all) (Table 2). We found no significant differences in rates of reported resiliency factors between male and female AI/AN students except for peer support, where female AI/AN students reported a significantly higher rate than male AI/AN students (56.2% vs 34.7%; P < .001).

Table 2.

Suicide indicators and resiliency factors among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) middle school students (N = 3018), by sex, 2019 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (NMYRRS) a

| Variable | Male students, % (95% CI) | Female students, % (95% CI) | P value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide indicators | |||

| Seriously thought about suicide | 19.4 (16.7-22.4) | 42.6 (39.5-45.9) | <.001 |

| Made a suicide plan | 10.7 (8.8-13.1) | 27.5 (24.6-30.7) | <.001 |

| Has attempted suicide | 7.7 (6.1-9.7) | 23.6 (20.5-27.0) | <.001 |

| Resiliency factors | |||

| Family support level c | .50 | ||

| High | 31.2 (28.2-34.4) | 33.5 (30.0-37.2) | |

| Moderate | 58.2 (55.1-61.3) | 55.8 (52.6-59.0) | |

| Low | 10.6 (8.6-13.0) | 10.7 (8.7-13.1) | |

| School support level c | .19 | ||

| High | 34.5 (30.0-38.8) | 30.2 (26.7-34.0) | |

| Moderate | 53.6 (50.0-57.2) | 57.9 (54.2-61.6) | |

| Low | 11.9 (8.7-16.1) | 11.9 (9.5-14.7) | |

| Community support level c | .34 | ||

| High | 26.5 (23.5-29.8) | 28.1 (25.2-31.3) | |

| Moderate | 54.6 (50.8-58.3) | 55.8 (52.6-58.9) | |

| Low | 18.9 (15.4-23.0) | 16.1 (13.5-19.2) | |

| Peer support level c | <.001 | ||

| High | 34.7 (31.1-38.2) | 56.2 (52.7-59.7) | |

| Moderate | 42.6 (39.2-46.1) | 30.7 (27.2-34.3) | |

| Low | 22.7 (20.0-25.7) | 13.1 (11.3-15.2) | |

Data source: 2019 NMYRRS. 27

Using the Pearson χ2 test to examine differences in the distribution of variables among AI/AN students stratified by sex, with significance set at α = .05.

Created by averaging response values for questions in each support category, yielding a possible range of 1 to 8 for the created construct variable: 1-4 = low level of support, 5-7 = moderate level of support, and 8 = high level of support.

Association Between Resiliency Factors and Suicide Indicators Among AI/AN Students

Among female AI/AN students, family, school, and community support were all significantly associated with decreased odds of all 3 suicide-related behaviors (Table 3). Among female AI/AN students, community support had the strongest protective effect against having seriously thought about suicide (aOR = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.14-0.38), while family support was significantly associated with the lowest odds of having made a suicide plan (aOR = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.28) and having attempted suicide (aOR = 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.34) (P < .001 for all).

Table 3.

Association between resiliency factors and suicide-related behaviors among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) middle school students (N = 3018), by sex, 2019 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (NMYRRS) a

| Resiliency factor b | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR c (95% CI) | P value d | aOR c (95% CI) | P value d | |

| Having seriously thought about suicide | ||||

| Family support level | .005 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.41 (0.22-0.76) | 0.24 (0.14-0.40) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| School support level | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.34 (0.19-0.62) | 0.36 (0.21-0.61) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Community support level | .16 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.64 (0.34-1.19) | 0.23 (0.14-0.38) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | .06 | |

| Peer support level | .40 | |||

| High | 0.82 (0.53-1.29) | 0.62 (0.38-1.02) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Having made a suicide plan | ||||

| Family support level | .02 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.40 (0.19-0.87) | 0.15 (0.08-0.28) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| School support level | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.19 (0.09-0.39) | 0.26 (0.14-0.49) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Community support level | .36 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.71 (0.34-1.48) | 0.20 (0.12-0.35) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Peer support level | .94 | .12 | ||

| High | 0.98 (0.51-1.87) | 0.67 (0.41-1.11) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Having attempted suicide | ||||

| Family support level | .02 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.42 (0.19-0.89) | 0.21 (0.13-0.34) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| School support level | .003 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.27 (0.12-0.65) | 0.31 (0.17-0.58) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Community support level | .07 | <.001 | ||

| High | 0.46 (0.20-1.05) | 0.31 (0.20-0.49) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Peer support level | .02 | .03 | ||

| High | 0.47 (0.25-0.87) | 0.54 (0.31-0.95) | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

Data source: 2019 NMYRRS. 27

Levels of support were quantified by averaging response values for questions in each support category, yielding a possible range of 1 to 8 for the created construct variable: 1-4 = low level of support, 5-7 = moderate level of support, and 8 = high level of support.

Logistic regression models for male and female students were created separately to determine the association between level of support and suicide indicators. Models were adjusted for grade, rural location of school, and location of school in relation to the nearest Tribal lands.

Using the Pearson χ2 test to examine differences in the distribution of variables among AI/AN students stratified by sex, with significance set at α = .05.

Among male AI/AN students, family and school support were significantly associated with decreased odds of each suicide outcome: having seriously thought about suicide, having made a suicide plan, and having attempted suicide (Table 3). Among male AI/AN students, school support had the strongest protective effect against all 3 outcomes: seriously thought about suicide (aOR = 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19-0.62; P < .001), having made a suicide plan (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.39; P < .001), and having attempted suicide (aOR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.12-0.65; P = .003). Community support was not significantly associated with any of the 3 suicide-related behaviors for male AI/AN students. For both male and female AI/AN students, the only suicide-related behavior that peer support was significantly protective against was having attempted suicide (males: aOR = 0.47 [95% CI, 0.25-0.87]; P = .02; females: aOR = 0.54 [95% CI, 0.31-0.95]; P = .03).

Discussion

This analysis demonstrates the value of AI/AN oversampling in public health surveillance systems, where we were able to double the overall number of AI/AN students participating in the biennial NMYRRS in 2019. With this increased sample size, we were sufficiently powered to perform in-depth analyses that resulted in several significant findings. This methodology has also enabled the production of unpublished Tribe- and school-specific reports, not presented here, which have been broadly used by Tribal and educational leaders to set priorities, make decisions, and monitor trends.

At the same time, the findings of our key analyses suggest that male and female AI/AN middle school students benefit from several sources of support when it comes to mitigating the odds of suicide-related behaviors. For female AI/AN middle school students, high levels of family support, school support, and community support were effective in mitigating the odds of having seriously thought about suicide, having made a suicide plan, and having attempted suicide. For male AI/AN middle school students, high levels of family and school support were protective against having seriously thought about suicide, having made a suicide plan, and having attempted suicide. These findings are consistent with patterns seen in New Mexico AI/AN high school students, although among male high school students, only support in the family/home was associated with decreased odds of suicide attempt. 25 This finding suggests that male AI/AN middle school students may be more open and responsive to multiple sources of support in middle school than in high school, possibly because sociocultural factors influence male AI/AN young people to become resistant to the acceptance, and benefits, of social support as they mature. This finding highlights the need for suicide intervention efforts tailored toward male AI/AN middle school students and points to the utility of school-based suicide interventions, which may be easier to implement than attempting to improve support in individual households.

Of note, peer support did not mitigate suicidal thoughts or plans among AI/AN students, although it was protective against suicide attempt among both male and female AI/AN students. The relationship between peer support and suicidality among AI/AN middle school students is not well understood, because most of the existing literature pertains to students in high school. These findings indicate that further study is warranted to understand the mechanism through which peer support mitigates suicide attempt among AI/AN middle school students.

Strengths

This study had several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first analysis to focus on identifying strength-based approaches to mitigating suicide-related behaviors among AI/AN middle school students. The results may help to inform more targeted studies to explore differential protective factor pathways by sex among AI/AN young people and the complex influence of peer support related to suicidality in this population.

Second, this analysis used data from a robust sample of AI/AN middle school students and highlights a novel approach to ensuring that AI/AN young people are routinely and accurately represented in a large, state-level surveillance system. To our knowledge, New Mexico is the only state that has created and added an AI/AN oversample protocol in its state-specific version of the CDC YRBSS. The creation and success of the AI/AN oversample project depend greatly on partnerships among Tribal, state, and academic partners, through which the NMYRRS is continuously calibrated to serve the unique culturally, racially, and ethnically diverse population of New Mexico. Such models can be used to increase AI/AN representation in other public health surveillance systems and to produce meaningful Tribe- and school-specific estimates.

Limitations

This study also had several limitations. First, all data included in this analysis were self-reported and may be subject to reporting bias. Second, the middle school NMYRRS contains fewer demographic variables than what is captured in the high school NMYRRS, which limited our ability to include more covariates in the logistic regression models. Of note, the middle school NMYRRS does not capture information related to gender, so the results of this analysis were based on sex assigned at birth.

Third, suicide-related behaviors are measured over the lifetime in the middle school NMYRRS, while resiliency factors are captured as current measures. This inconsistency in reporting periods should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings of this study.

Fourth, the authors acknowledge that analysis of resiliency factors within independent models does not address the potential interaction between protective factors across various domains of life (family, school, community, and peer relations), which requires more sophisticated analysis to fully understand. Fifth, measures of resiliency that are included in the NMYRRS instrument have been developed according to a Western model and might not fully capture what are considered to be sources of strength in Tribal communities.

Lastly, the 2019 NMYRRS was administered via scantron in schools, so these results are not applicable to young people who are homeschooled or who do not attend in-person school.

Conclusion

Oversampling allows schools and Tribal communities to more accurately characterize health risks and sources of strength that are unique to AI/AN young people and translate these data into responsive action. Through implementation of a robust AI/AN oversampling approach, we were able to produce meaningful, precise, and representative findings for this population. Family and school-based social support among male and female AI/AN middle school students and community support among female AI/AN students can mitigate suicide-related behaviors. However, more research is needed to understand the role of peer support as a potential protective factor against suicide attempt in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cynthia Garcia, BS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Liyanna Lee, BS, Northern Arizona University, for their assistance in conducting the literature review and formatting and reviewing this article. We also thank our partners at the University of New Mexico, the New Mexico Public Education Department, and Dan Green, MPH, at the New Mexico Department of Health for their support and collaboration on the NMYRRS project.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Indian Health Service Cooperative Agreement U1B1IHS0013.

ORCID iD: Carolyn Parshall, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5413-7246

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5413-7246

References

- 1. Langwell K, Helba C, Love C. Gaps and Strategies for Improving American Indian/Alaska Native/Native American Data. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. Accessed November 18, 2021. http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/07/AI-AN-NA-data-gaps

- 2. Waksberg J, Levine D, Marker D. Assessment of Major Federal Data Sets for Analyses of Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander Subgroups and Native Americans: Inventory of Selected Existing Federal Databases. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/reports/assessment-major-federal-data-sets-analyses-hispanic-asian-or-pacific-islander-subgroups-native

- 3. Watanabe-Galloway S, Duran T, Stimpson JP, Smith C. Gaps in survey data on cancer in American Indian and Alaska Native populations: examination of US Population Surveys, 1960-2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:120258. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strong DA, Del Grosso P, Burwick A, Jethwani V, Ponza M. Rural Research Needs and Data Sources for Selected Human Services Topics. Volume 1: Research Needs—Final Report. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files/113596/vol1.pdf

- 5. Elliott MN, Finch BK, Klein D, et al. Sample designs for measuring the health of small racial/ethnic subgroups. Stat Med. 2008;27(20):4016-4029. doi: 10.1002/sim.3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Underwood JM, Brener N, Thornton J, et al. Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020;69(1):1-10. doi: 10.15585/mwwr.su6901a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Massetti GM, Thomas CC, King J, Ragan K, Buchanan Lunsford N. Mental health problems and cancer risk factors among young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S30-S39. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiium N, Breivik K, Wold B. Growth trajectories of health behaviors from adolescence through young adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(11):13711-13729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121113711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mmari KN, Blum RW, Teufel-Shone N. What increases risk and protection for delinquent behaviors among American Indian youth? Findings from three Tribal communities. Youth Soc. 2010;41(3):382-413. doi: 10.1177/0044118X09333645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Henson M, Sabo S, Trujillo A, Teufel-Shone N. Identifying protective factors to promote health in American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents: a literature review. J Prim Prev. 2017;38(1-2):5-26. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying cause of death, 1999-2020. Updated November 3, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- 12. Ivanich JD, O’Keefe V, Waugh E, et al. Social network differences between American Indian youth who have attempted suicide and have suicide ideation. Community Ment Health J. 2022;58(3):589-594. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00857-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leavitt RA, Ertl A, Sheats K, Petrosky E, Ivey-Stephenson A, Fowler KA. Suicides among American Indian/Alaska Natives—National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 states, 2003-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(8):237-242. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Epidemiology and Response Division, New Mexico Department of Health. Youth who attempted suicide in the past year, by year, grades 9-12, New Mexico and U.S., 2001. to 2019. Updated March 5, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://ibis.doh.nm.gov/indicator/view/MentHlthYouthSuicAtt.Year.NM_US.html

- 15. New Mexico Department of Health. New Mexico suicide deaths increase in 2020. December 6, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.nmhealth.org/news/information/2021/12/?view=1739

- 16. Epidemiology and Response Division, New Mexico Department of Health. Suicide is preventable. July 2022. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.nmhealth.org/publication/view/general/6535

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 leading causes of death, United States, 2020, both sexes, all ages, all races. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home

- 18. New Mexico Department of Health. Mental health—youth attempted suicide. March 28, 2022. Updated March 5, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://ibis.doh.nm.gov/indicator/summary/MentHlthYouthSuicAtt.html

- 19. Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed suicide in adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:237-266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization. Suicide. June 17, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- 21. Borowsky IW, Resnick MD, Ireland M, Blum RW. Suicide attempts among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: risk and protective factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):573-580. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hummingbird LM. The public health crisis of Native American youth suicide. NASN Sch Nurse. 2011;26(2):110-114. doi: 10.1177/1942602X10397551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoder KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, LaFromboise T. Suicidal ideation among American Indian youths. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(2):177-190. doi: 10.1080/13811110600558240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bush A, Qeadan F. Social support and its effects on attempted suicide among American Indian/Alaska Native youth in New Mexico. Arch Suicide Res. 2020;24(suppl 1):337-359. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1577779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. FitzGerald CA, Fullerton L, Green D, Hall M, Peñaloza LJ. The association between positive relationships with adults and suicide-attempt resilience in American Indian youth in New Mexico. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2017;24(2):40-53. doi: 10.5820/aian.2402.2017.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) overview. Updated August 20, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2022. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm

- 27. New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey. What is the NM-YRRS? Updated 2022. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://youthrisk.org/#who-we-are

- 28. Constantine NA, Benard B. California Healthy Kids Survey Resilience Assessment Module: Technical Report. Public Health Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—2013 [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69(5152):1663]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-1):1-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freedenthal S, Stiffman AR. Suicidal behavior in urban American Indian adolescents: a comparison with reservation youth in a southwestern state. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(2):160-171. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.160.32789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manzo K, Hobbs GR, Gachupin FC, Stewart J, Knox SS. Reservation–urban comparison of suicidal ideation/planning and attempts in American Indian youth. J Sch Health. 2020;90(6):439-446. doi: 10.1111/josh.12891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]