Abstract

Background and Purpose.

In the chronic phase after a stroke, limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) initially plateau before steadily increasing. However, the benefits of pre-stroke levels of physical activity on these limitations remain unclear. To clarify this relationship, this study compares the effect of physical activity on the long-term evolution of I/ADL limitations between stroke survivors and stroke-free controls.

Methods.

Longitudinal data from 2,143 stroke survivors and 10,717 matched stroke-free controls aged 50 and over were drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE; 2004–2020). Physical activity was assessed on the wave preceding the stroke event and number of I/ADL limitations during the post-stroke chronic phase. Each stroke survivor was matched with 5 stroke-free controls who had similar propensity scores that were computed based on key covariates. The effect of pre-stroke physical activity on I/ADL limitations in stroke survivors was compared to its effect in stroke-free controls with a similar time lag between physical activity and I/ADL assessments using linear mixed-effects models adjusted for age, sex, education level, and the number of chronic conditions.

Results.

In stroke survivors, the beneficial effect of pre-stroke physical activity on ADL limitations after stroke is significantly stronger than its effect in stroke-free controls matched for baseline age, sex, body mass index, limitations in I/ADL, chronic conditions, and country of residence, before any of the participants had experienced a stroke.

Conclusions.

Physical activity is an effective preventive intervention that reduces the risk of functional dependence after stroke. In addition, pre-stroke level of physical activity is an important variable in the prognosis of functional dependence after stroke.

Keywords: Cohort studies, Comorbidity, Disability, Exercise, Functional status, Health behavior, Longitudinal studies, Prognosis, Prospective studies, Stroke survivors

Each year, the prevalence of stroke exceeds 100 million cases worldwide. On average, each of these cases is associated with a loss of 1.4 year of full health1,2. Over the past three decades, the number of years of full health lost to stroke has increased by an average of 1.2 million per year1. This burden on stroke survivors is reflected in their functional limitations. Specifically, one year after a stroke, 59%3–17, 33%13–28, and 23%11–13,15–20 of survivors experience at least slight, moderate, or severe dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs), respectively, such as dressing, walking, bathing, eating, and toileting (Table 1–3). Regarding instrumental ADLs (IADLs), 40%9,10,16,19,20 of stroke survivors are moderately active and 41%16,17,19–21 are inactive in domestic chores, leisure, work, and outdoor activities at one year (Table 4–5). Whether limitations in I/ADLs plateau10,13,21,28,29 or increase11,12,19 in subsequent years depends on several factors, including age11,12,29,30, type of health insurance11, and severity of disability 1 to 2 years after stroke12.

Table 1.

Stroke survivors with at least slight dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs) at 1 year follow-up.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Threshold | Sample Size (n) | Dependent Survivors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Appelros (2007) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 246 | 39.0 |

| Ayerbe (2011) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 1732 | 67.0 |

| Carolei (1997) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 517 | 61.7 |

| Dhamoon (2009) | Barthel Index | <95/100 | 525 | 48.1 |

| Gil-Salcedo (2022) | Modified Ranking Scale | >1/6 | 3718 | 63.8 |

| Hartman-Maeir (2007) | FIM motor scale | <91/91 | 56 | 68.0 |

| Leśniak (2008) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 80 | 43.7 |

| Mar (2015) | Barthel Index | <100/100 | 250 | 47.2 |

| Minelli (2007) | Barthel Index | <100/100 | 79 | 57.0 |

| Skånér (2007) | Katz ADL | <6/6 | 135 | 31.9 |

| Sveen (1996) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 74 | 58.1 |

| Taub (1994) | Barthel Index | <20/20 | 225 | 34.0 |

| van de Port (2006) | Barthel Index | <19/20 | 264 | 40.1 |

| Willey (2010) | Barthel Index | <95/100 | 246 | 44.7 |

| Wong (2014) | Modified Ranking Scale | >1/6 | 194 | 64.4 |

|

| ||||

| Total n | 8341 | |||

| Weighted mean (%) | 59.2 | |||

Note. FIM, Functional Independent Measure.

Table 3.

Stroke survivors with severe or total dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs) at 1 year follow-up.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Threshold | Sample Size (n) | Dependent Survivors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Appelros (2007) | Barthel Index | <12/20 | 246 | 16.0 |

| Broussy (2019) | Barthel Index | <12/20 | 161 | 12.7 |

| Dhamoon (2009) | Barthel Index | <60/100 | 525 | 18.0 |

| Gil-Salcedo (2022) | Modified Ranking Scale | >3/6 | 3718 | 27.3 |

| Mar (2015) | Barthel Index | <60/100 | 250 | 20.4 |

| Patel (2002) | Barthel Index | <10/20 | 619 | 9.4 |

| Patel (2003) | Barthel Index | <10/20 | 136 | 15.4 |

| Willey (2010) | Barthel Index | <60/100 | 246 | 15.9 |

| Wong (2014) | Modified Ranking Scale | >3/6 | 194 | 19.6 |

|

| ||||

| Total n | 6095 | |||

| Weighted mean (%) | 22.6 | |||

Table 4.

Stroke survivors who are moderately active in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) at 1 year follow-up.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Threshold | Sample Size (n) | Dependent Survivors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Appelros (2007) | Frenchay Activities Index | <30/45 | 246 | 78.8 |

| Ayerbe (2011) | Frenchay Activities Index | <30/45 | 1403 | 79.7 |

| Patel (2002) | Frenchay Activities Index | <30/45 | 619 | 85.7 |

| Patel (2003) | Frenchay Activities Index | <30/45 | 136 | 88.2 |

| Sveen (1996) | Frenchay Activities Index | <29/45 | 74 | 75.6 |

|

| ||||

| Total n | 2478 | |||

| Weighted mean (%) | 81.5 | |||

Table 5.

Stroke survivors who are inactive in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) at 1 year follow-up.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Threshold | Sample Size (n) | Dependent Survivors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Appelros (2007) | Frenchay Activities Index | <15/45 | 246 | 46.3 |

| Patel (2002) | Frenchay Activities Index | <15/45 | 619 | 40.4 |

| Patel (2003) | Frenchay Activities Index | <15/45 | 136 | 72.7 |

| van de Port (2006) | Frenchay Activities Index | <15/45 | 264 | 35.2 |

| Wolfe (2011) | Frenchay Activities Index | <15/45 | 1578 | 38.8 |

|

| ||||

| Total n | 2843 | |||

| Weighted mean (%) | 41.1 | |||

The level of physical activity has been suggested as one of the factors influencing functional limitations after stroke31. Regarding ADLs, some studies have found an association between higher prestroke physical activity and lower post-stroke disability in ADLs22,32–37. Specifically, higher pre-stroke physical activity was associated with higher independence in ADLs during the first22, 32–36 and second year37 after stroke. However, other studies found no evidence of this association between physical activity and functional independence in ADLs38–41. These mixed results could be explained by the use of a single-item rating scale22,32,33,35–41, the Modified Rankin Scale, which has been shown to be less reliable and more subjective than questionnaires assessing specific I/ADLs42. In addition, only one prospective study has examined the effect of physical activity before stroke on IADLs30. This study focused on vigorous physical activity and was based on a cohort of adults who were stroke-free at baseline. The results showed that higher vigorous physical activity at baseline was associated with a higher probability of being independent in I/ADLs after stroke, but this difference was similar before stroke. This result led the authors to conclude that “being physically active does not protect against the disabling effects of a stroke” on I/ADLs. Building on this previous study, we used a different approach by comparing the effect of physical activity on I/ADLs in a larger sample of stroke survivors (n = 2,143 vs. 1,374) with a sample of stroke-free controls matched for key covariates (n = 10,717). Moreover, because it has been suggested that moderate-intensity physical activity is at least as beneficial to brain plasticity as vigorous-intensity physical activity43,44, we included both intensities.

In this prospective cohort study, we hypothesized that the beneficial effect of pre-stroke moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on I/ADL limitations after stroke would be significantly stronger than its effect in stroke-free controls matched for baseline (i.e., before any of the participants had experienced a stroke) age, sex, body mass index, I/ADL limitations, and country of residence over a similar number of follow-up years.

Methods

Study Sample and Design

Data were drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a longitudinal population-based study on adults 50 years of age or older living in 28 European countries and one Middle East country45. Data were collected every two years between 2004 and 2020 for a total of 8 measurement waves using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in participants’ homes. Physical activity, stroke events, and functional independence (ADLs, IADLs) were assessed at all measurement waves except wave 3 (2008–2009). To be included in the present study, participants had to be 50 years of age or older, have never reported having a stroke before entering the study, and have participated in at least 4 waves. SHARE was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Mannheim (waves 1–4) and the Ethics Council of the Max Plank Society (waves 4–8). All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Outcome variable: Functional limitations

Functional dependence was assessed using the number of functional dependencies in six ADLs (dressing, walking, bathing, eating, getting in or out of bed, and using the toilet) and seven IADLs (using a map, preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making telephone calls, taking medication, gardening or doing housework, and managing money)46,47. Higher scores were indicative of higher functional dependence.

Explanatory variables: Stroke and physical activity

Information on stroke status during follow-up was collected at each wave using the following question: “Has a doctor told you that you have any of the conditions on this card [indicating history of health conditions including stroke]?”12.

The level of physical activity at entry in SHARE was derived from two questions: “How often do you engage in vigorous physical activity, such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labor?” and “How often do you engage in activities that require a low or moderate level of energy such as gardening, cleaning the car, or doing a walk?”47–52. Participants answered using a four-point scale: 1 = Hardly ever or never; 2 = One to three times a month; 3 = Once a week; 4 = More than once a week. Participants who answered “more than once a week” to at least one of the questions were classified as physically active, whereas the other participants were classified as physically inactive to reduce a potential misclassification bias in which physically inactive participants would be wrongly classified as physically active.

Covariates

Models were adjusted for baseline age, sex (male, female), time (survey waves), quadratic time, number of chronic conditions (none or 1 vs. 2 or more), and level of education, which has shown to be associated with the level of physical activity48,51,53–57.

Data Preprocessing

Matching procedure

To select matched samples of stroke survivors and stroke-free participants with similar distributions of key covariates, a matching procedure based on the nearest neighbor method was conducted using the MatchIt R package58,59 with propensity scores obtained with a generalized linear model. This matching process used a 1:5 ratio to create groups including one stroke survivor and five stroke-free controls with similar propensity scores, thereby reducing the potential bias introduced by covariates. Propensity scores were calculated using characteristics of the participants at their first interview for the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), i.e., when none of them had experienced a stroke: Age, sex, number of chronic conditions (none or 1 vs. 2 or more), limitations in I/ADL, body mass index category [underweight (below 18.5 kg/m2), normal (reference; 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25 to 29.9 kg/m2), obese (30 kg/m2 and above)], country of residence, number of measurement waves, and wave number of the first interview.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models that account for the nested structure of the data (i.e., repeated measurement over time within a single participant) and provide acceptable Type I error rates60. The models were built and fit by maximum likelihood in R programming language61 using the lme462 and lmerTest63 packages. P-values were approximated using the Satterthwaite’s method64. Specifically, to investigate the effect of pre-stroke physical activity on functional independence in stroke survivors and stroke-free controls, two dependent variables were tested: ADL and IADL limitations. The fitted models included stroke (stroke vs. no stroke), physical activity (active vs. inactive at baseline), linear time, quadratic time, and the covariates as fixed effects. The random structure encompassed random intercepts for participants and for participants grouped together by the matching process as well as random linear and quadratic slopes for the repeated measurements at the level of participants. These random effects estimated each participant’s and each matching group’s functional independence as well as the rate of change of this independence over time. The quadratic effect of age was added to account for the potential accelerated (or decelerated) decline of functional independence across time. An interaction terms between stroke and physical activity was added to formally test the moderating effect of stroke on the association between physical activity and functional dependence.

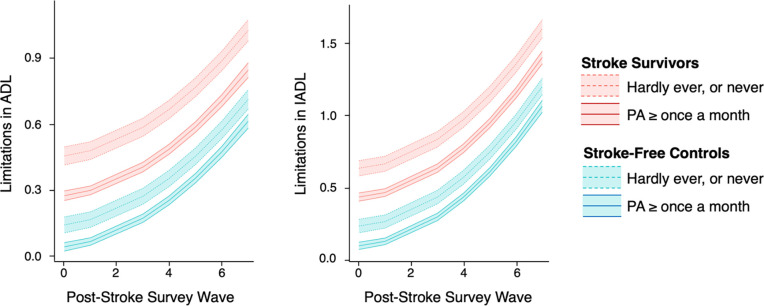

Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, participants who answered “hardly ever or never” to one of the two questions related to the level of physical activity were classified as physically inactive, whereas the other participants were classified as physically active. This categorization reduced a potential misclassification bias in which physically active participants would wrongly be classified as physically inactive.

Results

The study sample included 2,143 stroke survivors (mean age: 66.9 ± 9.1 years; 1,052 females) and 10,717 stroke-free controls (mean age: 66.9 ± 9.3 years, 5,126 females) whose characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Baseline characteristics of the participants at their first interview for the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), when none of them had experienced a stroke, stratified by stroke-related status in the following waves.

| Variables | Stroke Survivors (N = 2,143) | Stroke-Free Controls (N = 10,717) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.9 (9.1) | 66.9 (9.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Female, n (%) | 1052 (49.1) | 5126 (47.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 1091 (50.9) | 5591 (52.2) |

| Physical Activity | ||

| Hardly ever or never, n (%) | 1193 (55.7) | 6311 (58.9) |

| ≥ Once a month, n (%) | 950 (44.3) | 4403 (41.1) |

| < Once a week, n (%) | 1553 (72.5) | 8014 (74.8) |

| ≥ Once a week, n (%) | 590 (27.5) | 2703 (25.2) |

| Functional Limitations | ||

| ADL, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.7) |

| IADL, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.9) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | ||

| < 18.5 – Underweight, n (%) | 155 (1.5) | 590 (1.1) |

| 18.5–24.9 – Normal, n (%) | 3445 (33.9) | 16275 (31.7) |

| 25–29.9 – Overweight, n (%) | 4176 (41.0) | 22856 (44.5) |

| ≥ 30 – Obese, n (%) | 2401 (23.6) | 11647 (22.7) |

| Chronic Condition | ||

| < 2, n (%) | 3423 (32.7) | 22807 (43.5) |

| ≥ 2, n (%) | 7053 (67.3) | 29676 (56.5) |

| Education | ||

| Primary, n (%) | 666 (31.1) | 3027 (28.2) |

| Secondary, n (%) | 1081 (50.4) | 5415 (50.5) |

| Tertiary, n (%) | 396 (18.5) | 2275 (21.2) |

| Country | ||

| Austria, n (%) | 147 (6.9) | 764 (7.1) |

| Belgium, n (%) | 193 (9.0) | 965 (9.0) |

| Czech Republic, n (%) | 160 (7.5) | 818 (7.6) |

| Denmark, n (%) | 170 (7.9) | 810 (7.6) |

| Estonia, n (%) | 154 (7.2) | 870 (8.1) |

| France, n (%) | 161 (7.5) | 815 (7.6) |

| Germany, n (%) | 153 (7.1) | 831 (7.8) |

| Greece, n (%) | 106 (4.9) | 506 (4.7) |

| Israel, n (%) | 95 (4.4) | 460 (4.3) |

| Italy, n (%) | 161 (7.5) | 768 (7.2) |

| Luxembourg, n (%) | 20 (0.9) | 94 (0.9) |

| Netherlands, n (%) | 81 (3.8) | 384 (3.6) |

| Poland, n (%) | 73 (3.4) | 368 (3.4) |

| Slovenia, n (%) | 76 (3.5) | 379 (3.5) |

| Spain, n (%) | 141 (6.6) | 673 (6.3) |

| Sweden, n (%) | 167 (7.8) | 812 (7.6) |

| Switzerland, n (%) | 85 (4.0) | 404 (3.8) |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living, SD = standard deviation.

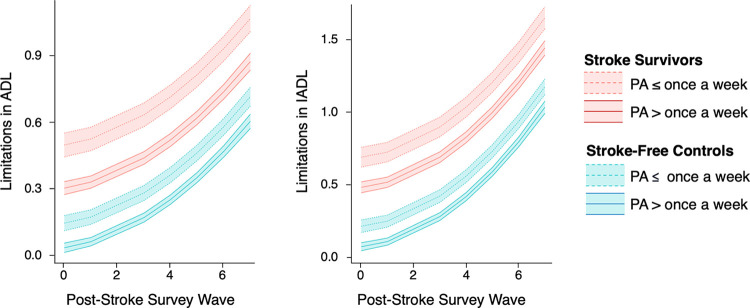

Results of the mixed-effects models showed an interaction effect between stroke and physical activity on limitations in ADL (b = 0.083, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.018 to 0.148, p = 0.013; Table 7, Figure 1). The simple effects of the terms of this interaction confirmed that the effect of physical activity was stronger in stroke survivors (b = 0.268, 95% CI: 0.241 to 0.296, p < 2.0 × 10−16) than in stroke-free controls (b = 0.351, 95% CI: 0.292 to 0.411, p < 2.0 × 10−16).

Table 7.

Results of the mixed-effects models testing the interaction between stroke-related status and physical activity (once a week or less vs. more than once a week) on limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

| ADL | IADL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Exposures | b (95 CI) | p | b (95 CI) | p |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | −0.563 (−0.655 to −0.470) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | −1.298 (−1.415 to −1.182) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Stroke | −0.111 (−0.144 to −0.078) | 4.2 × 10−11 | 0.141 (0.100 to 0.182) | 1.9 × 10−11 |

| Physical Activity | 0.351 (0.292 to 0.411) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.410 (0.375 to 0.444) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Wave | 0.018 (0.008 to 0.028) | 3.5 × 10−4 | 0.018 (0.006 to 0.031) | 0.004 |

| Wave2 | 0.009 (0.008 to 0.010) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.017 (0.151 to 0.189) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Age | 0.008 (0.007 to 0.009) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.014 (0.013 to 0.016) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Sex | 0.072 (0.050 to 0.094) | 1.5 × 10−10 | 0.203 (0.174 to 0.231) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary (vs. Secondary) | 0.115 (0.090 to 0.140) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.219 (0.187 to 0.251) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Tertiary (vs. Secondary) | −0.025 (−0.054 to 0.003) | 0.081 | −0.044 (−0.080 to −0.008) | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| Chronic Conditions | 0.121 (0.106 to 0.136) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.188 (0.170 to 0.206) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Stroke × Physical Activity | −0.083 (−0.149 to −0.018) | 0.012 | 0.067 (−0.016 to 0.149) | 0.116 |

Note. 95CI = 95% confidence interval, ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Figure 1.

Effect of physical activity (PA: once a week or less vs. more than once a week) on limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in stroke survivors and matched stroke-free controls over time.

For IADL, results showed no evidence of an interaction effect between stroke and physical activity on limitations in IADL (b = 0.067, 95% CI: −0.016 to 0.149, p = 0.149; Table 7, Figure 1).

Results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with the results to the main analyses (Table 8; Figure 2).

Table 8.

Results of the sensitivity analyses testing the interaction between stroke-related status and physical activity (hardly ever or never vs. at least once a month) on limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

| Exposures | ADL | IADL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| b (95CI) | p | b (95CI) | p | |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | −0.494 (−0.589 to −0.399) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | −1.042 (−1.168 to −0.917) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Stroke | −0.096 (−0.133 to −0.058) | 6.2 × 10−7 | −0.130 (−0.177 to −0.082) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Physical Activity | 0.309 (0.256 to 0.362) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.382 (0.314 to 0.449) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Wave | 0.019 (0.009 to 0.029 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 0.021 (0.008 to 0.033) | 0.001 |

| Wave2 | 0.009 (0.007 to 0.010) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.017 (0.015 to 0.019) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Age | 0.007 (0.005 to 0.008) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.012 (0.011 to 0.014) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Sex | 0.062 (0.040 to 0.084) | 4.2 × 10−8 | 0.192 (0.163 to 0.221) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary (vs. Secondary) | 0.119 (0.104 to 0.133) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.185 (0.167 to 0.203) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Tertiary (vs. Secondary) | 0.116 (0.091 to 0.141) | < 2.0 × 10−16 | 0.223 (0.191 to 0.255) | < 2.0 × 10−16 |

| Chronic Conditions | −0.027 (−0.056 to 0.002) | 0.064 | −0.049 (−0.085 to −0.012) | 0.009 |

| Stroke × Physical Activity | −0.086 (−0.144 to −0.028) | 0.004 | −0.065 (−0.138 to 0.009) | 0.086 |

Note. 95CI = 95% confidence interval, ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Figure 2.

Result of the sensitivity analysis showing the effect of physical activity (PA: Hardly ever or never vs. at least once a month) on limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in stroke survivors and matched stroke-free controls over time.

Discussion

Main Results

The results of this large cross-national longitudinal study suggest that the beneficial effect of pre-stroke physical activity on in ADL limitations after stroke is significantly stronger than its effect in stroke-free controls matched for age, sex, body mass index, limitations in I/ADLs, chronic conditions, and country of residence, before any of the participants had experienced a stroke.

Comparison With Other Studies

Our results showed that higher levels of pre-stroke physical activity were associated with fewer ADL limitations. These fin dings are in line with the existing literature showing that an association between higher pre-stroke physical activity and lower post-stroke disability in ADLs22,32–37. Our findings support these results. Most importantly, they reveal that the effect of pre-stroke physical activity on in ADL limitations after stroke is significantly stronger than its effect in matched stroke-free controls. While the study by Ris et al.30 also examined the effect of physical activity on both stroke survivors and stroke-free controls (without the matching procedure we conducted), this potential interaction effect was not considered.

Several mechanisms could explain how physical activity enhances post-stroke functional independence. This effect could be explained by an association between pre- and post-stroke physical activity as previous studies showed that this level was similar in 41 to 42% of stroke survivors activity65,66. This post-stroke engagement in physical activity could increase brain plasticity processes such as angiogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis, primarily through the upregulation of growth factors (e.g., brain-derived neuro- trophic factor; BDNF)67–69. However, the same studies also showed that 33 to 39% of stroke survivors reported lower physical activity after compared to before stroke, and 20 to 25% reported higher physical activity65,66. Another explanation could be the protective effect of pre-stroke physical activity on depression65, which has shown to be associated with ADL limitations47,70,71.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has several strengths including results presented for a long follow-up period (up to 16 years) and a large international post-stroke population (17 countries), which allowed us to robustly examine the effects of physical activity on I/ADL limitations. The number of I/ADL limitations used to evaluate changes in functional limitation over time, which are more reliable than single-item rating and more sensitive to identify differences in functional trajectory between stroke cases and controls. The sensitivity results using different categories for physical activity were consistent with the main results.

However, our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. (1) There was a lack of information on stroke subtypes, which is common in and inherent to large-scale longitudinal studies. Future studies should be supported by medical records to provide a more specific understanding of the relationship between physical activity and functional independence in stroke survivors. (2) The outcome (i.e., stroke) was self-reported. Therefore, a memory bias cannot be excluded. However, the agreement between self-reported stroke and medical records ranges from 79%72 to 96%73. (3) Physical activity was self-reported, which may not have accurately captured the actual levels of physical activity, as correlations between self-report and direct measures of physical activity are low to moderate74,75. Future studies should assess physical activity using device-based measures, as they have shown greater validity and reliability76.

Conclusion

Our findings support a stronger long-term beneficial effect of physical activity on independence in ADLs in stroke survivors compared with stroke-free adults. These findings underscore the essential preventive role of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in mitigating stroke-related limitations in ADLs. In addition, these findings highlight the need to consider the pre-stroke levels of physical activity in the prognosis of stroke-related functional independence.

Table 2.

Stroke survivors with at least moderate dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs) at 1 year follow-up.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Threshold | Sample Size (n) | Dependent Survivors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Appelros (2007) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 246 | 31.2 |

| Broussy (2019) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 161 | 29.6 |

| De Campos (2017) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 287 | 16.4 |

| Jokinen (2015) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 364 | 44.0 |

| López-Cancio (2017) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 143 | 53.8 |

| Mar (2015) | Barthel Index | <90/100 | 250 | 40.4 |

| Patel (2002) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 619 | 36.2 |

| Patel (2003) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 136 | 36.0 |

| Santus (1990) | Barthel Index | <75/100 | 76 | 46.1 |

| Taub (1994) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 225 | 11.0 |

| Urbanek (2018) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 1119 | 41.6 |

| Verhoeven (2011) | Barthel Index | <18/20 | 92 | 38.0 |

| Wafa (2020) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 1961 | 24.1 |

| Wolfe (2011) | Barthel Index | <15/20 | 1578 | 13.1 |

| Wong (2014) | Modified Ranking Scale | >2/6 | 194 | 33.0 |

|

| ||||

| Total (n) | 7451 | |||

| Weighted mean (%) | 32.9 | |||

Acknowledgements

Based on the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT)77,78, individual author contributions to this work are as follows:

• Zack Van Allen: Writing – Review and Editing.

• Dan Orsholits: Methodology; Formal Analysis; Visualization; Data Curation; Writing – Review and Editing.

• Matthieu P. Boisgontier: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Visualization; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing; Supervision; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition.

Funding

Dr Boisgontier is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), Mitacs, and the Banting Research Foundation. Zack Van Allen is supported by a Mitacs-Banting Discovery Postdoctoral Fellowship. The SHARE data collection was primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001–00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006–062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005–028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006–028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: no.211909, SHARE-LEAP: no.227822, SHARE M4: no.261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740–13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553–01, IAG_BSR06–11, OGHA_04–064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The other authors declare that they have no financial conflict of interest related to the content of this article. Matthieu P. Boisgontier is the founder, representative, and manager of Peer Community In (PCI) Health & Movement Sciences (https://healthmovsci.peercommunityin.org/about), a free and transparent peer review service provided by a community of researchers who review and recommend preprints. He is a former co-chair and current member of the Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology (STORK; https://storkinesiology.org), current editor-in-chief for Communications in Kinesiology (https://storkjournals.org/index.php/cik), and associate editor for the European Rehabilitation Journal (https://rehab-journal.com), both of which are Diamond Open Access journals publishing articles in the field of health and rehabilitation sciences.

Code and supplemental material are publicly available online: https://github.com/matthieu-boisgontier/Stroke_Physical-Activity

Data and Code Sharing

The SHARE dataset is available at http://www.share-project.org/data-access.html and the DOIs for the waves used in the current study are: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w1.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w2.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w7.711, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w8cabeta.001.

References

- 1-.GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(10):795–820. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2-.World Health Organization. Indicator metadata registry list: Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). Accessed January 29, 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/158

- 3-.Carolei A, Marini C, Di Napoli M, et al. High stroke incidence in the prospective community-based L’Aquila registry (1994–1998). First year’s results. Stroke. 1997;28(12):2500–2506. 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4-.Hartman-Maeir A, Soroker N, Ring H, Avni N, Katz N. Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(7):559–566. 10.1080/09638280600924996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5-.Leśniak M, Bak T, Czepiel W, Seniów J, Człon-kowska A. Frequency and prognostic value of cognitive disorders in stroke patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(4):356–363. 10.1159/000162262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6-.Minelli C, Fen LF, Minelli DP. Stroke incidence, prognosis, 30-day, and 1-year case fatality rates in Matão, Brazil: a population-based prospective study. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2906–2911. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.484139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7-.Skånér Y, Nilsson GH, Sundquist K, Hassler E, Krakau I. Self-rated health, symptoms of depression and general symptoms at 3 and 12 months after a first-ever stroke: a municipality-based study in Sweden. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:61. 10.1186/1471-2296-8-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8-.van de Port IG, Kwakkel G, van Wijk I, Lindeman E. Susceptibility to deterioration of mobility long-term after stroke: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2006;37(1):167–171. 10.1161/01.STR.0000195180.69904.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9-.Sveen U, Wyller TB, Ljunggren AE, Bautz-Holter E. Predictive validity of early cognitive assessment in stroke rehabilitation, Scand J Occup Ther. 1996;3(1):20–27. 10.3109/11038129609106678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10-.Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Rudd AG, Heuschmann PU, Wolfe CD. Natural history, predictors, and associations of depression 5 years after stroke: the South London Stroke Register. Stroke. 2011;42(7):1907–1911. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11-.Dhamoon MS, Moon YP, Paik MC, et al. Long-term functional recovery after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2805–2811. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.549576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12-.Gil-Salcedo A, Dugravot A, Fayosse A, et al. Long-term evolution of functional limitations in stroke survivors compared with stroke-free controls: findings from 15 years of follow-upacross 3 international surveys of aging. Stroke. 2022;53(1):228–237. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13-.Willey JZ, Disla N, Moon YP, et al. Early depressed mood after stroke predicts long-term disability: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study (NOMASS). Stroke. 2010;41(9):1896–1900. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14-.Taub NA, Wolfe CD, Richardson E, Burney PG. Predicting the disability of first-time stroke sufferers at 1 year. 12-month follow-up of a population-based cohort in southeast England. Stroke. 1994;25(2):352–357. 10.1161/01.str.25.2.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15-.Wong GK, Lam SW, Wong A, et al. MoCA-assessed cognitive function and excellent outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage at 1 year. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(5):725–730. 10.1111/ene.12363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16-.Appelros P. Characteristics of the Frenchay Activities Index one year after a stroke: a population-based study. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(10):785–790. 10.1080/09638280600919715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17-.Mar J, Masjuan J, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Outcomes measured by mortality rates, quality of life and degree of autonomy in the first year in stroke units in Spain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:36. 10.1186/s12955-015-0230-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18-.Broussy S, Saillour-Glenisson F, García-Lorenzo B, et al. Sequelae and quality of life in patients living at home 1 year after a stroke managed in stroke units. Front Neurol. 2019;10:907. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19-.Patel MD, Coshall C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Cognitive impairment after stroke: clinical determinants and its associations with long-term stroke outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(4):700–706. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20-.Patel M, Coshall C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Natural history of cognitive impairment after stroke and factors associated with its recovery. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(2):158–166. 10.1191/0269215503cr596oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21-.Wolfe CD, Crichton SL, Heuschmann PU, et al. Estimates of outcomes up to ten years after stroke: analysis from the prospective South London Stroke Register. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1001033. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22-.Urbanek C, Gokel V, Safer A, et al. Low self-reported sports activity before stroke predicts poor one-year-functional outcome after first-ever ischemic stroke in a population-based stroke register. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):181. 10.1186/s12883-018-1189-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23-.Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(9):1288–1294. 10.1111/ene.12743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24-.López-Cancio E, Jovin TG, Cobo E, et al. Endovascular treatment improves cognition after stroke: A secondary analysis of RE-VASCAT trial. Neurology. 2017;88(3):245–251. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25-.Santus G, Ranzenigo A, Caregnato R, Inzoli MR. Social and family integration of hemiplegic elderly patients 1 year after stroke. Stroke. 1990;21(7):1019–1022. 10.1161/01.str.21.7.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26-.Verhoeven CL, Post MW, Schiemanck SK, van Zandvoort MJ, Vrancken PH, van Heugten CM. Is cognitive functioning 1 year poststroke related to quality of life domain? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20(5):450–458. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebro-vasdis.2010.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27-.Wafa HA, Wolfe CDA, Bhalla A, Wang Y. Long-term trends in death and dependence after ischaemic strokes: a retrospective cohort study using the South London Stroke Register (SLSR). PLoS Med. 2020;17(3):e1003048. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28-.de Campos LM, Martins BM, Cabral NL, et al. How many patients become functionally dependent after a stroke? A 3-year population-based study in Joinville, Brazil. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170204. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29-.Rejnö Å, Nasic S, Bjälkefur K, Bertholds E, Jood K. Changes in functional outcome over five years after stroke. Brain Behav. 2019;9(6):e01300. 10.1002/brb3.1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30-.Rist PM, Capistrant BD, Mayeda ER, Liu SY, Glymour MM. Physical activity, but not body mass index, predicts less disability before and after stroke. Neurology. 2017;88(18):1718–1726. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31-.Viktorisson A, Reinholdsson M, Danielsson A, Palstam A, S Sunnerhagen K. Pre-stroke physical activity in relation to post-stroke outcomes - linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): A scoping review. J Rehabil Med. 2022;54:jrm00251. 10.2340/jrm.v53.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ursin MH, Ihle-Hansen H, Fure B, Tveit A, Bergland A. Effects of premorbid physical activity on stroke severity and post-stroke functioning. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(7):612–617. 10.2340/16501977-1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deplanque D, Masse I, Lefebvre C, Libersa C, Leys D, Bordet R. Prior TIA, lipid-lowering drug use, and physical activity decrease ischemic stroke severity. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1403–1410. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240057.71766.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroud N, Mazwi TM, Case LD, et al. Prestroke physical activity and early functional status after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(9):1019–1022. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.170027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen CP, Liu CH, Jeng JS, et al. Pre-stroke physical activity is associated with fewer post-stroke complications, lower mortality and a better long-term outcome. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(12):1525–1531. 10.1111/ene.13463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricciardi AC, López-Cancio E, Pérez de la Ossa N, et al. Prestroke physical activity is associated with good functional outcome and arterial recanalization after stroke due to a large vessel occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37(4):304–311. 10.1159/000360809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krarup LH, Truelsen T, Gluud C, et al. Prestroke physical activity is associated with severity and long-term outcome from first-ever stroke. Neurology. 2008;71(17):1313–1318. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327667.48013.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morovatdar N, Di Napoli M, Stranges S, et al. Regular physical activity postpones age of occurrence of first-ever stroke and improves long-term outcomes. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(8):3203–3210. 10.1007/s10072-020-04903-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rist PM, Lee IM, Kase CS, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Physical activity and functional outcomes from cerebral vascular events in men. Stroke. 2011;42(12):3352–3356. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.619544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damsbo AG, Mortensen JK, Kraglund KL, Johnsen SP, Andersen G, Blauenfeldt RA. Prestroke physical activity and poststroke cognitive performance. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;49(6):632–638. 10.1159/000511490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Decourcelle A, Moulin S, Sibon I, et al. Influence of previous physical activity on the outcome of patients treated by thrombolytic therapy for stroke. J Neurol. 2015;262(11):2513–2519. 10.1007/s00415-015-7875-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe CD, Taub NA, Woodrow EJ, Burney PG. Assessment of scales of disability and handicap for stroke patients. Stroke. 1991;22(10):1242–1244. 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;60:56–64. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marin Bosch B, Bringard A, Logrieco MG, Lauer E, Imobersteg N, Thomas A, Ferretti G, Schwartz S, Igloi K. A single session of moderate intensity exercise influences memory, endocannabinoids and brain derived neurotrophic factor levels in men. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14371. 10.1038/s41598-021-93813-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, et al. Data Resource Profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):992–1001. 10.1093/ije/dyt088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landös A, von Arx M, Cheval B, et al. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: a European cohort study. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(1):50–58. 10.1093/eurpub/cky166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boisgontier MP, Orsholits D, von Arx M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, depressive symptoms, Functional Dependence, and physical activity: A moderated mediation model. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(8):790–799. 10.1123/jpah.2019-0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheval B, Maltagliati S, Saoudi I, Fessler L, Farajzadeh A, Sieber S, Cullati S, Boisgontier MP. Physical activity mediates the effect of education on mental health trajectories in older age. J Affect Disord. 2023;336:64–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheval B, Orsholits D, Sieber S, Courvoisier D, Cullati S, Boisgontier MP. Relationship between decline in cognitive resources and physical activity. Health Psychol. 2020;39(6):519–528. 10.1037/hea0000857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheval B, Rebar AL, Miller MW, Sieber S, Orsholits D, Baranyi G, Courvoisier D, Cullati S, Sander D, Chalabaev A, Boisgontier MP. Cognitive resources moderate the adverse impact of poor perceived neighborhood conditions on self-reported physical activity of older adults. Prev Med. 2019;126:105741. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheval B, Saoudi I, Maltagliati S, Fessler L, Farajzadeh A, Sieber S, Cullati S, Boisgontier MP. Initial status and change in cognitive function mediate the association between academic education and physical activity in adults over 50 years of age. Psychol Aging. 2023. 10.1037/pag0000749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheval B, Sieber S, Guessous I, Orsholits D, Courvoisier DS, Kliegel M, Stringhini S, Swinnen SP, Burton-Jeangros C, Cullati S, Boisgontier MP. Effect of early- and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances on physical inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(3):476–485. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beenackers MA, Kamphuis CB, Giskes K, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in occupational, leisure-time, and transport related physical activity among European adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:116. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clouston SA, Richards M, Cadar D, Hofer SM. Educational inequalities in health behaviors at midlife: is there a role for early-life cognition? J Health Soc Behav. 2015;56(3):323–340. 10.1177/0022146515594188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Droomers M, Schrijvers CT, Mackenbach JP. Educational level and decreases in leisure time physical activity: predictors from the longitudinal GLOBE study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(8):562–568. 10.1136/jech.55.8.562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kari JT, Viinikainen J, Böckerman P, et al. Education leads to a more physically active lifestyle: Evidence based on Mendelian randomization. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30(7):1194–1204. 10.1111/sms.13653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Donoghue G, Kennedy A, Puggina A, et al. Socio-economic determinants of physical activity across the life course: A “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella literature review. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190737. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal. 2007;15(3):199–236. 10.1093/pan/mpl013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho D, Imai K, King G, Stuart E, Whitworth A, Greife N. MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference [R package]. Version 4.5.4; 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MatchIt/MatchIt.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boisgontier MP, Cheval B. The anova to mixed model transition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:1004–1005. 10.1016/j.neubio-rev.2016.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. https://www.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, Dai B, Scheipl F, Grothendieck G, Green P, Fox J, Bauer A, Krivitsky PN. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using ‘eigen’ and S4 [R package]. Version 1.1–27.1; 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/lme4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest: tests in linear mixed effects models [R package]. Version 3.1–3; 2016. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/lmerTest.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bovim MR, Indredavik B, Hokstad A, Cumming T, Bernhardt J, Askim T. Relationship between pre-stroke physical activity and symptoms of post-stroke anxiety and depression: an observational study. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(10):755–760. 10.2340/16501977-2610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viktorisson A, Andersson EM, Lundström E, Sunnerhagen KS. Levels of physical activity before and after stroke in relation to early cognitive function. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9078. 10.1038/s41598-021-88606-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(9):464–472. 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gibbons TD, Cotter JD, Ainslie PN, Abraham WC, Mockett BG, Campbell HA, Jones EMW, Jenkins EJ, Thomas KN. Fasting for 20 h does not affect exercise-induced increases in circulating BDNF in humans. J Physiol. 2023;601(11):2121–2137. 10.1113/JP283582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):58–65. 10.1038/nrn2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hadidi N, Treat-Jacobson DJ, Lindquist R. Poststroke depression and functional outcome: a critical review of literature. Heart Lung. 2009;38(2):151–162. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai SM, Duncan PW, Keighley J, Johnson D. Depressive symptoms and independence in BADL and IADL. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39(5):589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engstad T, Bonaa KH, Viitanen M. Validity of self-reported stroke: the Tromso Study. Stroke. 2000;31(7):1602–1607. 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van den Akker M, van Steenkiste B, Krutwagen E, Metsemakers JF. Disease or no disease? Disagreement on diagnoses between self-reports and medical records of adult patients. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015;21(1):45–51. 10.3109/13814788.2014.907266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:115. 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:56. 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dowd KP, Szeklicki R, Minetto MA, Murphy MH, Polito A, Ghigo E, van der Ploeg H, Ekelund U, Maciaszek J, Stemplewski R, Tomczak M, Donnelly AE. A systematic literature review of reviews on techniques for physical activity measurement in adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):15. 10.1186/s12966-017-0636-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Allen L, O’Connell A, Kiermer V. How can we ensure visibility and diversity in research contributions? How the Contributor Role Taxonomy (CRediT) is helping the shift from authorship to contributorship. Learn Publ. 2019;32(1):71–74. 10.1002/leap.1210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brand A, Allen L, Altman M, Hlava M, Scott J. Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit. Learn Publ. 2015;28:151–155. 10.1087/20150211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The SHARE dataset is available at http://www.share-project.org/data-access.html and the DOIs for the waves used in the current study are: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w1.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w2.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w7.711, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w8cabeta.001.