Abstract

The treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has always been a real challenge for dermatologists; to date, the only biologic drugs approved for HS are adalimumab, an anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α drug, authorized in 2015, and secukinumab, recently licensed. The management of this condition is challenging as the available treatments show variable results, and the course of the condition is often chronic-recurrent; therefore, it will be necessary for the future to identify new therapeutic targets for HS. In recent years, studies have focused on the development towards new therapeutic targets. The purpose of our review was to perform a comprehensive literature review of real-life data on anti-IL23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab) in HS to summarize the existing evidence on the efficacy and safety of these drugs. We selected 64 articles, among which 32 had the characteristics that we were looking for in our review. To date, the positive data expressed in real-life experiences contrast with the three existing Phase 2 studies conducted so far, where it seems that these drugs may be useful only for a subgroup of patients with HS whose features need to be elucidated. Data from Phase 3 studies and other real-life experiences, perhaps more detailed and with higher numbers, will certainly be needed to fully understand the efficacy and safety of this class of drugs.

Keywords: hidradenitis suppurativa, anti-IL23, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab, real life evidence

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa or Verneuil’s disease, is a chronic, inflammatory, recurrent, and debilitating skin disease of the hair follicles, characterized by inflammatory, painful, and deep-rooted lesions in body areas characterized by the presence of apocrine glands.1,2 Although the exact mechanism of HS has not been entirely elucidated, lesion formation is believed to be centered around follicular hyperkeratosis within the pilosebaceous-apocrine unit.3,4 Recent research has provided new insights into the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of HS, helping close existing knowledge gaps in the development of this condition.3,4 In particular, several pro-inflammatory mediators have been reported to play a key role in the formation of inflammatory nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and sinus tracts such as Interferon (IFN)-γ, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-17, and IL-12/23.4 Moreover, several comorbidities are often associated with HS including obesity, metabolic syndrome, and autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s disease, which negatively affect both the treatment of this pathology and the quality of life of patients with HS.5,6 The treatment of HS has always been a real challenge for dermatologists. Historically, the only biologic drug approved for HS is adalimumab, an anti-TNF-α drug, approved in 2015.7–10 The results of this drug in real life evidence have been discussed for years where it would seem that this drug can achieve a success rate of about 70%.7–10 Recently, Secukinumab, an anti-IL 17 drug, has been approved, showing effective results in clinical trials, improving the signs and symptoms of HS with a good safety profile and response for up to 52 weeks.11 Real-life data were also in line with the studies carried out.11 The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has approved secukinumab for use in adults with active moderate-to-severe HS and an inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy.12

Globally, the management of HS is very difficult as the treatments available to date show variable results, and the course of the condition is often chronic-recurrent; therefore, it will be necessary for the future to identify new therapeutic targets for HS. In recent years, studies have focused on the development towards new therapeutic targets.13

Bimekizumab, the latest available IL-17 inhibitor on the market, is a humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F,14 and has shown promising results in a recently published phase 2 study.15 Among the new therapeutic targets, there has been much discussion in recent years regarding the role of anti-interleukin-23 drugs and their use in the treatment of HS. To date, there have been few phase 2 studies on these drugs and various case reports and case series with highly variable results. The purpose of our review was to perform a comprehensive literature review of real-life data on anti-IL23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab) in HS to summarize the existing evidence on the efficacy and safety of these drugs.

Methods

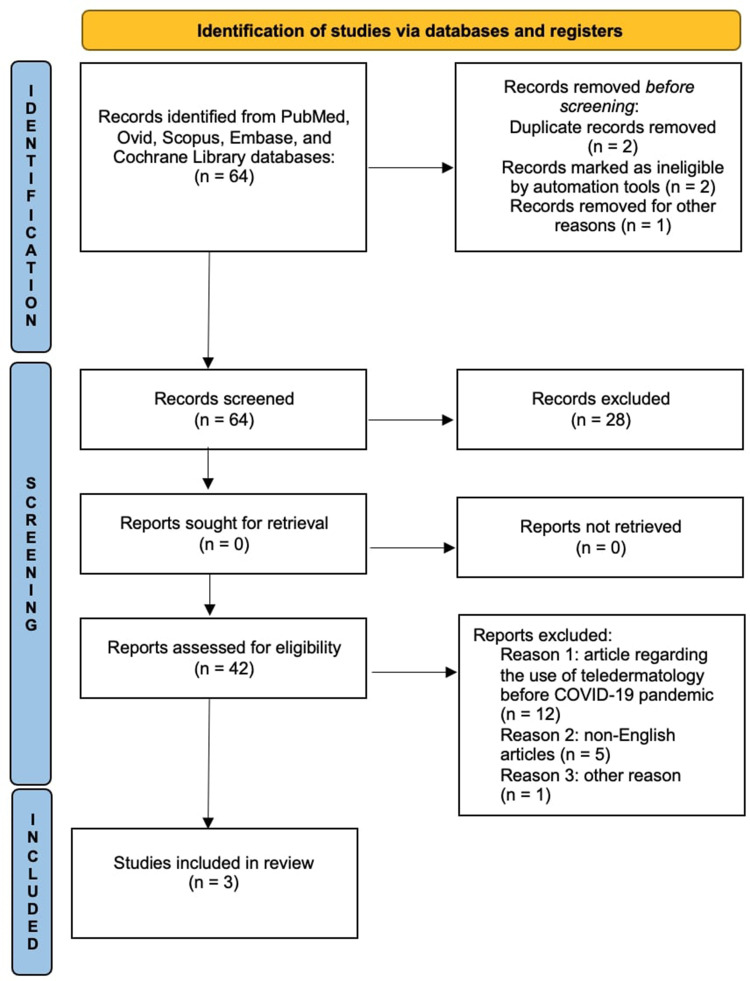

A comprehensive review of the English-language medical literature was performed using the PubMed, Ovid, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases from their inception until May 2023 using Medical Subject Headings (mesh) (if applicable) and medical terms for the concepts of guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab use in a real-life setting. The search strategy to identify articles was performed using the following search terms: “IL-23 inhibitors”, “guselkumab”, “tildrakizumab”, “risankizumab”, AND “real life”, AND “real world evidence”, AND “hidradenitis suppurativa”, hidradenitis suppurativa. The search involved all fields, including the title, abstract, keywords, and full-text. Clinical and epidemiological studies, reviews, and systematic reviews of the use of guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab in real-world settings were included. Only English language manuscripts were included in this study. This article is based on previous studies and does not include any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Manuscripts were identified, screened, and extracted for relevant data following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines16 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma checklist.

Notes: PRISMA figure adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. Creative Commons.17

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) placebo- or active comparator-controlled human studies; (2) trials focusing on the efficacy and safety of IL-23 inhibitors in HS; (3) randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with at least one of the following outcomes reported: Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and adverse events; and real-life evidence has been includedin particular, letters to editors, case reports, and case series, as there are still very few reports in the literature. The quality of the enrolled studies was evaluated using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs.16

Results

We selected 64 articles, among which 32 had the characteristics that we were looking for in our review. This section will be divided into subparagraphs in which the efficacy and safety data present in the literature on IL-23 will be reported.

Tildrakizumab

Tildrakizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG1-k) against interleukin-23, particularly with a high affinity for the p19 subunit, and is approved for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.18,19

To date, no clinical trials or large-scale studies have reported on the use of tildrakizumab in HS. There were two case series with a total of nine patients and two case reports of tildrakizumab treatment for HS.

Kot et al20 published a case series of 5 patients with HS treated with tildrakizumab. Four patients had Hurley stage III disease, and one patient had Hurley stage II disease. Assessments were performed at weeks 8 and 20 with registered data according to the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and number of lesions; however, there were no data on the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4) or Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR). The authors reported a mean reduction in abscess and nodule count of 16.8 (P=0.04) at week 8 from baseline; data were confirmed at week 20. In addition, all patients reported improvement in their quality of life. There were no reported side effects reported, but one patient had to discontinue treatment at week 8 due of pregnancy.20

The same authors21 published other data with a total of 9 HS patients also including five patients from their previous case series with up to 15 months of treatment. Of these nine patients, only four had 15 months of treatment with tildrakizumab alone, while the other subjects received antibiotic therapies with clindamycin, rifampicin, or resorcinol for 15 months. Only 1 patient underwent corticosteroid therapy (prednisone) because of pyoderma gangrenosum as a comorbidity. Two patients required deroofing procedures, and two patients underwent incision and drainage. According to the authors, this does not affect the treatment outcomes. Moreover, the authors only evaluated the DLQI and the number of lesions, while there were no more precise data on IHS4 and HiSCR. The authors reported a statistically significant reduction in mean abscess and nodule count of 23.50 (P = 0.032) at month 15.21 Regarding the DLQI, the authors reported that the data did not reach statistical significance because the initial DLQI was low. No adverse events were reported, and the only report was a non-drug-related diarrhea episode lasting 3 days, which did not affect treatment, while the patient who discontinued treatment for pregnancy at week 8 did not report pregnancy sequelae or fetal abnormalities.21

Dasmin22 recently described the case of a 38-year-old patient with HS and psoriasis who had previously failed adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab, and was therefore switched to tildrakizumab. Prior to treatment, the patient had Hurley stage 2 and a Hidradenitis Suppurativa-Physician Global Assessment (HS-PGA) score of 4 (ie, severe). HiSCR was achieved at week 40 with complete remission of psoriasis (PASI100), Hurley stage 2, and HS-PGA score 2 (mild). The results were confirmed at week 52, and the authors reported no side effects.22

The other case described in the literature concerns a case of a 50-year-old patient affected by PASH syndrome who had had a significant worsening of HS;23 the patient had practiced in the past with only limited benefit unspecified antibiotic therapy and adalimumab (interrupted for ineffectiveness); therefore, the authors report having started treatment with tildrakizumab. At baseline, the patient had an abscess and nodule count of 45, DLQI score of 26, and visual analog scale (VAS) pain score of 10 was reported.23 After 5 months of treatment, the patient presented with an abscess and nodule count of 5 and a VAS score of 7 but a DLQI score of 19. No side effects during the treatment were reported by the authors during treatment.23

We believe that there are still insufficient data to express an opinion on the efficacy of tildrakizumab in HS. The lack of large-scale data or more accurate evaluation parameters, such as IHS4 and HiSCR, represents a real limitation of existing literature. In the future, we hope to review other more detailed articles, such as psoriasis.24–29

Risankizumab

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that specifically inhibits interleukin 23 (IL-23) by binding to its p19 subunit. Risankizumab has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and Crohn’s disease.30 Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of this drug in these conditions.31–36 However, there are few reports on the use of this drug in HS. In particular, there has been a recently published phase 2 study and some case reports.

Kimball et al37 recently conducted a Phase II multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to investigate the efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe HS. A total of 243 patients were enrolled in this study. There were two treatment periods in this study. The first ranged from week 0 to week 16, which was randomized in a double-blind study in which patients received a 1:1:1 ratio of placebo, risankizumab 180 mg, and risankizumab 360 mg. The second period ranged from week 16 to week 68, when treatment was open-label with risankizumab. The primary endpoint was the achievement of HiSCR after the first double-blind period after 16 weeks of treatment, and the data were compared after week 68 of risankizumab open-label treatment.37 The proportion of patients who met the endpoint after week 16 was very similar for patients who received risankizumab 180 mg or risankizumab 360 mg versus those who received placebo (46.8% vs 43.4% vs 41.5%); therefore, not having reached the planned endpoint, the study was terminated early.37 In this study, as in other studies performed on HS, a high placebo effect was reported, probably because of the chronic relapsing course of HS.38 Additional efficacy and safety data from this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Risankizumab from Clinical Trial

| Authors | Study Design | Patient Enrolled | Effectiveness | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kimball et al37 | Phase II multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03926169) |

A total of 243 patients were randomized (risankizumab 180 mg, n = 80; risankizumab 360 mg, n = 81; placebo, n = 82) | HiSCR was achieved by 46.8% of patients with risankizumab 180 mg, 43.4% with risankizumab 360 mg, and 41.5% with placebo at week 16 |

Double-blind period: headache (10.6%), nasopharyngitis (8.1%), back pain (4.4%), urinary tract infection (4.4%), fatigue (3.8%), nausea (3.1%), upper respiratory tract infection (3.1%), and worsening of hidradenitis suppurativa (3.1%) Open label period: worsening of hidradenitis suppurativa (11.0%), headache (5.5%), and diarrhea (3.7%) No deaths were reported. |

Repetto et al39 conducted a retrospective study from November 2020 to December 2021 with 6 patients enrolled, 4 with Hurley Stage III and two patients had Hurley Stage II. All patients had previously received adalimumab treatment, and none were bionaived. No concomitant treatment with risankizumab has been described. The HS was evaluated using IHS4 and HiSCR. Of the six patients, three achieved HiSCR at month 3, and all patients achieved HiSCR at month 6. There were no statistically significant data instead regarding IHS4, all patients reported a marked improvement in their quality of life. The authors concluded that none of the patients experienced adverse events.39

Licata et al40 described the case of a 50-year-old patient with psoriasis and HS who had previously failed cyclosporine and adalimumab therapies. The patient was staged as Hurley stage 2 with a PASI of 25 and a BSA of 20, and after 16 weeks of treatment, the authors reported complete resolution of both pathologies. There are no detailed data on HS in this article from the authors; IHS4 or HiSCR are missing, and it is not clear whether there were any side effects.40

Marques et al41 described two cases of patients who first achieved HiSCR with adalimumab and then discontinued therapy due to loss of efficacy. The two patients were staged before risankizumab treatment with Hurley III scores, IHS4 scores of 28 and 43, DLQI scores of 19 and 25, VAS of 5.9 and 7.5, respectively. The results after 4 months of therapy were as follows: for patient 1: reduction of IHS4 from 28 to 4, DLQI from 19 to 5, and VAS from 5.9 to 2, whereas for patient 2, reduction of IHS4 from 43 to 6, DLQI from 25 to 9, and VAS from 7.5 3.1.41

No adverse events other than one episode of tonsillitis were reported in patient 1, which did not affect the treatment.41 Caro et al42 reported the case of a 39-year-old female with HS, psoriasis vulgaris, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. He had undergone various antibiotic therapies and surgery for recurrence, and biological therapy with adalimumab and secukinumab was interrupted due to lack of efficacy. Therefore, the treatment with risankizumab was initiated with the addition of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole 160 + 800 mg twice a day for 1 month. The authors reported an improvement at week 4 (no data of IHS4 or HiSCR), whereas at week 16, they reported a reduction in IHS4 from 18 to 4 and a reduction in DLQI from 20 to 2.42 The results were maintained for 24 weeks. The therapy was well tolerated, and no adverse events were observed.42

The data reported for risankizumab were more consistent than those for tildrakizumab, involving a higher number of subjects. Although good results have been reported in case reports and case series, the only existing phase 2 study concluded that risankizumab does not appear to be an effective treatment for moderate-to-severe HS. Further phase 3 studies with a higher sampling will be needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this drug for the treatment of HS, as well as for other drugs currently under discussion.43–47

Guselkumab

Guselkumab is a human monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) lambda antibody directed against IL-23 that has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and PsA.48,49 Several studies of psoriasis and PsA have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of this drug.50,51 There are also several reports in the literature regarding HS, in particular, there have been two recent phase 2 studies and several case reports and/or case series.

Dudink et al52 recently conducted an open-label, multicentre, phase IIa trial, 20 patients were enrolled, and the study lasted 24 weeks divided into 16 weeks of treatment and 8 weeks of follow-up; the primary endpoint was achievement of HiSCR at week 16. Almost 65% of patients (n = 13/20) achieved HiSCR and 35% (n = 7/20) achieved a 75% improvement in HiSCR.48 The authors conclude the study stating that IL-23 inhibition does not appear to be central to the pathophysiology of HS and that guselkumab has been shown to be effective only in certain subtypes of HS patients.52

Additional study data regarding efficacy, safety, and study limitations are reported in Table 2

Table 2.

Data Guselkumab from Clinical Trial

| Authors | Study Design | Patient Enrolled | Effectiveness | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dudink et al52 | An open-label, multicentre, phase IIa trial | 20 patients enrolled. 2 drop out. Limitation of study: Low sampling and lack of a placebo arm |

65% of patients (n = 13/20) achieved HiSCR and 35% (n = 7/20) reached a 75% improvement in HiSCR. The median IHS4 and AN count decreased significantly between baseline and week 16, from 8.5 (IQR 4.3–16.0) to 5.0 |

The most common adverse events were headache, infections (most frequently upper respiratory tract infections), and nausea. The only serious adverse event was a myocardial infarction that occurred after 16 weeks of treatment. This event was not related to current therapy |

| Kimball et al53 | A phase 2, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study | 184 patients enrolled 3 drop out Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive: 1) guselkumab 200 mg by subcutaneous (SC) injection every 4 weeks (q4w) through Week 36 (the guselkumab SC group); 2) guselkumab 1200 mg intravenously (IV) every q4w for 12 weeks, then guselkumab 200 mg SC q4w from Weeks 12–36 (the guselkumab IV group); or 3) placebo IV or SC q4w for 12 weeks, with re- randomization to guselkumab 200 mg SC q4w at Weeks 16–36 (the placebo→guselkumab 200 mg group) or guselkumab 100 mg SC at Weeks 16, 20, 28, and 36 and placebo at Weeks 24 and 32 (the placebo→guselkumab 100 mg group). |

At Week 16, the proportions of patients who achieved HiSCR were numerically higher in the guselkumab SC (50.8%, p=0.166) and guselkumab IV (45.0%, p=0.459) groups versus the placebo group (38.7%); however, the differences were not statistically significant. At Week 40, HiSCR response rates were 45.8% and 48.3% in the guselkumab SC and IV groups, respectively, and 46.4% and 53.6% in the placebo→guselkumab 100 mg and placebo→guselkumab 200 mg groups, respectively. |

Serious adverse events (SAEs): 1 patient in guselkumab group had anemia and nephrolithiasis. 1 patient had cholelithiasis. No patients experienced a major adverse cardiovascular event, malignancy, anaphylactic reaction, or serum sickness reaction; there were no deaths. |

Kimball et al53 recently conducted a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 184 enrolled patients. The study was set up for 36 weeks of treatment and included 4 arms: guselkumab, intravenous guselkumab, guselkumab from weeks 12 to 36, and the placebo group. The primary endpoint was HiSCR 16, 40, and 4 weeks after the end of treatment. The secondary endpoints were IHS4 and AN counts at weeks 16 and 40.53

Although guselkumab SC or IV resulted in numerically higher HiSCR than the placebo at week 16 (50.8%, 45.0%, and 38.7%, respectively), statistical significance was not achieved.53 The results did not improve at week 40, and the authors concluded that the primary endpoint was not met; therefore, guselkumab did not appear to be effective.53 Additional data regarding safety and efficacy are presented in Table 2.

Casseres et al54 conducted a retrospective chart review of eight patients, four patients with Hurley stage III and four patients with Hurley stage II, who had previously failed therapies with adalimumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab, and ixekizumab. The authors reported an improvement in five patients (63%) after 4 months of therapy but did not provide precise score data.

Jorgensen et al55 described the case of a young patient with HS and Crohn’s disease who failed adalimumab and ustekinumab therapies. The authors speak of a marked improvement after 7 months of therapy without providing detailed data on IHS4 or HiSCR but confirmed this improvement even after 12 months.55

Vilchez et al56 described a case series of four patients treated with guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks, and all patients had been previously treated with either adalimumab, secukinumab, or ustekinumab. The authors reported a moderate reduction in the IHS4, VAS for pain, and DLQI after 12 weeks of treatment.56

No guselkumab-related adverse events were observed in any patient.56 Another interesting case was described by Kearney et al,57 the authors reported a case of a 28-year-old female patient with a history of latent tuberculosis who had been treated for HS. The authors did not report other treatments but reported that they started treatment with guselkumab, reporting a clear clinical and pain improvement after 12 weeks of therapy. No therapy-related adverse events.57

Kovac et al58 reported a case series of three patients, of whom two had already failed adalimumab, while adalimumab was contraindicated for the third patient because of cardiovascular concerns. All the patients were assessed for IHS4, DLQI, and VAS pain at week 12. The mean IHS4 was 21.3 before treatment and decreased to 9.3 after 12 weeks of treatment.58 The authors reported a reduction in the DLQI and VAS scores. No side effects reported.58

Burzi et al59 reported a case of concomitant HS and paradoxical psoriasiform reaction to adalimumab that was successfully treated with guselkumab.59 Before treatment, the patient was staged with an IHS4 of 50. After 4 weeks of therapy with guselkumab, he had an IHS4 of 9 with a VAS score of 0 and a DLQI score of 6. (There were no data before DLQI treatment.)

Other reports concern paradoxical HS reactions successfully treated with guselkumab,60–62 which is very important, as it reinforces the usefulness of this drug in some subgroups of patients, such as those suffering from paradoxical HS.63 In conclusion, among the anti-interleukin-23 drugs, guselkumab has the most numerous reports on HS. Again, the data from the case reports and case series were positive, while the phase 2 studies did not confirm this positive trend that had been described. All studies conducted so far have concluded that this drug would not seem to be effective in all patients, but only in a subgroup of HS patients.

Miscellaneous

Repetto et al conducted a pilot study with 26 patients in whom adalimumab therapy failed. Of these 26, 10 patients started treatment with IL23 drugs (7 risankizumab and 3 guselkumab), while the other 16 started treatment with Secukinumab.1 patient among the IL23 group discontinued due to ineffectiveness.64

The authors reported a significant difference in HiSCR (p=0.0272) between the two groups, with better rates in the IL23 group after 6 months of treatment.64

IHS4 was 17.1 (range 8–40) at baseline; at 12 months, mean IHS4 scores of 5.1 (range 0–20) and 14.1 (range 0–30) were recorded in the anti-IL-23 and anti-IL-17 groups, respectively, with a significant improvement compared with baseline achieved only in the IL-23 group (p=0.0027 vs p=0.0926). No severe side effects were observed in either group.64

Discussion

Patients with HS require long-term management and frequent follow-up owing to the highly recalcitrant nature of the disease, and first-line therapies such as antibiotics fail to guarantee severe forms of HS.65–67 Biologic drugs have certainly been a positive breakthrough for HS; these drugs have already been used for other conditions such as psoriasis, where they have shown excellent results in terms of efficacy and safety, even during the years of the COVID-19 pandemic.65–84

To date, adalimumab has been approved for the treatment of HS, and its efficacy and safety have been proven in several clinical trials and in real life.7–9 The future scenario features secukinumab, which has shown promising results in clinical trials and real life in several published studies83 and recently European Commission approved its use in adults with active moderate-to-severe HS and an inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy.12

The efficacy of these drugs has not achieved complete resolution of the disease; therefore, new therapeutic targets need to be identified in the future. In recent years, there has been much discussion about the role of IL 23 in this pathology, and several published papers have reported how the IL23/TH17 pathways could play a role in the pathogenesis of HS, particularly because IL-23 is overexpressed in the lesions of HS patients along with increased serum levels of IL-23 in HS subjects.84–90

This has been the main reason supporting the use of these drugs in recent years, as we reported, the early data seemed very promising; however, the published phase 2 studies confirmed that there is less effective absorption of these drugs toward HS lesions than, for example, psoriasis, which results in a more modest therapeutic response. To date, phase 2 studies, particularly those by Kimball et al53 showed only modest effects on the serum proteins associated with the IL-23 pathway. This confirms how it is necessary in the future studies using lesional tissue from HS patients will be crucial in this regard in order to understand the real role these drugs may play in HS. None of the three phase 2 studies published thus far (two guselkumab studies and one risankizumab study) reached their target endpoints, and even the risankizumab study ended early; therefore, the results of the phase 3 studies will be needed to understand where to place these drugs in the management of HS.

The number of therapies available for HS will certainly increase in the coming years to be able to choose a personalized approach for each patient based on comorbidities. In addition to the drugs described in our review, there are reports on the use of spesolimab (anti-IL-36 receptor) and JAK inhibitors, whose clinical trials are ongoing; thus far, there have been very few reports expressing a definitive opinion.91,92

Strengths and Limitations

The main focus was a systematic and detailed review of the articles. However, adalimumab is the only approved drug; therefore, there are still few reports with other drugs, and the lack of phase 3 studies is certainly another important limitation in the final complex.

Conclusion

New knowledge of HS pathogenesis, particularly on the ILs involved, is leading to the development of new, selective, and effective drugs with a high safety profile. In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first review that brings together all case reports, case series, and trials conducted so far for anti-interleukin-23 in HS. To date, the positive data expressed in real-life experiences contrast with the three existing phase 2 studies conducted so far, where it seems that these drugs may be useful only for a subgroup of patients with HS whose features need to be elucidated. Data from Phase 3 studies and other real-life experiences, perhaps more detailed and with higher numbers, will certainly be needed to fully understand the efficacy and safety of this class of drugs.

Data Sharing Statement

Data are reported in the current study and are on request by the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas, took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chiricozzi A, Veraldi S, Fabbrocini G, et al. The Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) “multidisciplinary unit”: a rationale and practical proposal for an organised clinical approach. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(2):274–275. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2018.3254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martora F, Martora L, Fabbrocini G, Marasca C. A case of pemphigus vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa: may systemic steroids be considered in the standard management of hidradenitis suppurativa? Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8(3):265–268. doi: 10.1159/000521712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1045–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephan C, Kurban M, Abbas O. Reply to: hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):e371. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen TV, Damiani G, Orenstein LAV, Hamzavi I, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on epidemiology, phenotypes, diagnosis, pathogenesis, comorbidities and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(1):50–61. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martora F, Ruggiero A, Battista T, Potestio L, Megna M. Comment on: associations between hidradenitis suppurativa and dermatological conditions in adults: a national cross-sectional study by Brown et al. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;2023:llad156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):422–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemec GBE, Okun MM, Forman SB, et al. Adalimumab medium-term dosing strategy in moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: integrated results from the Phase III randomized placebo-controlled PIONEER trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(5):967–975. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term Adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):60–69.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martora F, Megna M, Battista T, et al. Adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the real-life experience. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:135–148. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S391356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimball AB, Jemec GBE, Alavi A, et al. Secukinumab in moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa (SUNSHINE and SUNRISE): week 16 and week 52 results of two identical, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10378):747–761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novartis Europharm Limited. Cosentyx® (secukinumab): summary of product characteristics. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cosentyx-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2023.

- 13.Camela E, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Ruggiero A, Megna M. New frontiers in personalized medicine in psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(12):1431–1433. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2022.2113872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggiero A, Potestio L, Martora F, et al. Bimekizumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a drug safety evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(5):355–362. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2023.2218086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glatt S, Jemec GBE, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of bimekizumab in moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(11):1279–1288. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276–288. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31279-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinclair R, ThirtharPalanivelu V. Tildrakizumab for the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1544493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Howard A, Varigos G, Kern J, Dolianitis C. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(4):e488–e490. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Dolianitis C. Tildrakizumab as a potential long-term therapeutic agent for severe Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a 15 months experience of an Australian institution. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62(2):e313–e316. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damsin T. A case of concurrent psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa successfully treated with tildrakizumab. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13:1611–1615. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00940-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, Howard A, Dolianitis C. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(3):e373–e374. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potestio L, Piscitelli I, Fabbrocini G, et al. Efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in a patient with chronic HBV infection. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16(16):369–373. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S403294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galluzzo M, D’adamio S, Bianchi L, Talamonti M. Tildrakizumab for treating psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17(5):645–657. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1304537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggiero A, Potestio L, Cacciapuoti S, et al. Tildrakizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: results from a single center preliminary real-life study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(12):e15941. doi: 10.1111/dth.15941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Megna M, Tommasino N, Potestio L, et al. Real-world practice indirect comparison between guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab: results from an Italian 28-week retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(6):2813–2820. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2081655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blauvelt A, Chiricozzi A, Ehst BD, Lebwohl MG. Safety of IL-23 p19 inhibitors for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2023;40(8):3410–3433. doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02568-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campione E, Lambiase S, Gaeta Shumak R, et al. A real-life study on the use of tildrakizumab in psoriatic patients. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(4):526. doi: 10.3390/ph16040526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skyrizi (risankizumab-rzaa). Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 KEEPsAKE 1 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):225–231. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Megna M, Camela E, Battista T, et al. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecules for psoriasis in pediatric and geriatric populations. Part I: focus on pediatric patients. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(1):25–41. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2023.2173170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaçi D, et al. Risankizumab compared with Adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10198):576–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30952-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Megna M, Ruggiero A, Battista T, Marano L, Cacciapuoti S, Potestio L. Long-term efficacy and safety of risankizumab for moderate to severe psoriasis: a 2-year real-life retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(9):3233. doi: 10.3390/jcm12093233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650–661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31713-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martora F, Villani A, Ocampo-Garza SS, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Alopecia universalis improvement following risankizumab in a psoriasis patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(7):e543–e545. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimball AB, Prens EP, Passeron T, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13(5):1099–1111. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00913-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amir Ali A, Seng EK, Alavi A, Lowes MA. Exploring changes in placebo treatment arms in hidradenitis suppurativa randomized clinical trials: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(82):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Repetto F, Burzi L, Ribero S, Quaglino P, Dapavo P. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case series. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00780. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.2926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Licata G, Gambardella A, Buononato D, et al. A case of moderate hidradenitis suppurativa and psoriasis successfully treated with risankizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(4):e126–e129. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marques E, Arenberger P, Smetanová A, Gkalpakiotis S, Zimová D, Arenbergerová M. Successful treatment of recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa with risankizumab after failure of anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(5):966–967. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caposiena Caro RD, Pensa C, Lambiase S, Candi E, Bianchi L. Risankizumab effectiveness in a recalcitrant case of hidradenitis suppurativa after anti-TNF and anti-interleukin-17 failures. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6):e15116. doi: 10.1111/dth.15116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martora F, Scalvenzi M, Ruggiero A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and JAK inhibitors: a review of the published literature. Medicina. 2023;59(4):801. doi: 10.3390/medicina59040801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Genco L, Martora F, Potestio L, Patruno C. Rapid improvement in pruritus in atopic dermatitis patients treated with upadacitinib: a real-life experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(9):1497–1498. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, Puig L. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi: 10.1177/20406223211055920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markota Čagalj A, Marinović B, Bukvić Mokos Z. New and emerging targeted therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3753. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Megna M, Camela E, Battista T, et al. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecules for psoriasis in pediatric and geriatric populations. Part II: focus on elderly patients. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(1):43–58. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2023.2173171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blauvelt A, Burge R, Gallo G, et al. A retrospective cohort analysis of treatment patterns over 1 year in patients with psoriasis treated with ixekizumab or guselkumab. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(3):701–714. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00686-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruggiero A, Picone V, Martora F, et al. Guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab in the management of psoriasis: a review of the real-world evidence. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1649–1658. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S364640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the Phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):418–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reich K, Armstrong AW, Langley RG, et al. Guselkumab versus secukinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis (ECLIPSE): results from a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10201):831–839. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31773-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dudink K, Bouwman K, Chen Y, et al. Guselkumab for hidradenitis suppurativa: a Phase II, open-label, mode-of-action study. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(5):601–609. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimball AB, Podda M, Alavi A, et al. Guselkumab for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a phase 2 randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Casseres RG, Kahn JS, Her MJ, Rosmarin D. Guselkumab in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):265–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jørgensen AR, Holm JG, Thomsen SF. Guselkumab for hidradenitis suppurativa in a patient with concomitant Crohn’s disease: report and systematic literature review of effectiveness and safety. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8(12):2874–2877. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montero-Vilchez T, Martinez-Lopez A, Salvador-Rodriguez L, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. The use of guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks on patients with hidradenitis suppurativa and a literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13456. doi: 10.1111/dth.13456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kearney N, Byrne N, Kirby B, Hughes R. Successful use of guselkumab in the treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45(5):618–619. doi: 10.1111/ced.14199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kovacs M, Podda M. Guselkumab in the treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):e140–e141. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burzi L, Repetto F, Ramondetta A, et al. Guselkumab in the treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa, a promising role? Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(3):e14930. doi: 10.1111/dth.14930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Croitoru DO, Seigel K, Nathanielsz N, et al. Treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa and fistulizing Crohn’s disease with guselkumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(7):e563–e565. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garcia-Melendo C, Vilarrasa E, Cubiró X, Bittencourt F, Puig L. Sequential paradoxical psoriasiform reaction and sacroiliitis following Adalimumab treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa, successfully treated with guselkumab. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14180. doi: 10.1111/dth.14180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martora F, Fabbrocini G, Marasca C, et al. Paradoxical hidradenitis suppurativa induced by Adalimumab biosimilar successfully treated with guselkumab in a patient with psoriasis. Comment on ‘Paradoxical hidradenitis suppurativa due to anti-interleukin-1 agents for mevalonate kinase deficiency successfully treated with the addition of ustekinumab’. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48(6):701–703. doi: 10.1093/ced/llad082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruggiero A, Martora F, Picone V, et al. Paradoxical hidradenitis suppurativa during biologic therapy, an emerging challenge: a systematic review. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2):455. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Repetto F, Roccuzzo G, Burzi L, et al. Drug survival of anti interleukin-17 and interleukin −23 agents after adalimumab failure in hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103(103):adv5278. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v103.5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martora F, Marasca C, Picone V, et al. How adalimumab impacts antibiotic prescriptions in patients affected by hidradenitis suppurativa: a 1-year prospective study and retrospective analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):837. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian hidradenitis suppurativa foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martora F, Villani A, Battista T, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. COVID-19 vaccination and inflammatory skin diseases. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(1):32–33. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martora F, Villani A, Marasca C, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. Skin reaction after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines Reply to ‘cutaneous adverse reactions following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose: a real-life multicentre experience’. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(1):e43–e44. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu JJ, Liu J, Thatiparthi A, et al. The risk of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;S0190–9622(22):2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martora F, Fabbrocini G, Nappa P, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions of patients with rare diseases: an experience of a Southern Italy referral center. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(7):e237–e238. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Megna M, Potestio L, Battista T, et al. Immune response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in patients with psoriasis undergoing treatment with biologics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(47):2310–2312. doi: 10.1111/ced.15395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martora F, Fabbrocini G, Nappa P, et al. Reply to Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV −2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(10):e750–e751. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mintoff D, Benhadou F. Guselkumab does not appear to influence the IgG antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(2):e15246. doi: 10.1111/dth.15246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ruggiero A, Martora F, Picone V, et al. The impact of COVID-19 infection on patients with psoriasis treated with biologics: an Italian experience. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2280–2282. doi: 10.1111/ced.15336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marasca C, Fornaro L, Martora F, Picone V, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Onset of vitiligo in a psoriasis patient on ixekizumab. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5):e15102. doi: 10.1111/dth.15102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martora F, Marasca C, Battista T, et al. Management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa during COVID-19 vaccination: an experience from southern Italy. Comment on: ‘Evaluating the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa’. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(11):2026–2028. doi: 10.1111/ced.15306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pakhchanian H, Raiker R, DeYoung C, Yang S. Evaluating the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(6):1186–1188. doi: 10.1111/ced.15090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Bettoli V, Jemec GBE, et al. Anti-COVID-19 measurements for hidradenitis suppurativa patients. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(Suppl 1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/exd.14339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martora F, Marasca C, Fabbrocini G, et al. Strategies adopted in a southern Italian referral centre to reduce Adalimumab discontinuation: comment on ‘Can we increase the drug survival time of biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa?’. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(10):1864–1865. doi: 10.1111/ced.15291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Picone V, Martora F, Fabbrocini G, et al. “Covid arm”: abnormal side effect after Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(1):e15197. doi: 10.1111/dth.15197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, D’Agostino M, et al. Cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination: the evidence says “less fear”. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(1):28–29. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Potestio L, Villani A, Fabbrocini G, et al. Cutaneous reactions following booster dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination: what we should know? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(11):5339–5340. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ring HC, Frew JW, Thyssen JP, Egeberg A, Thomsen SF. Can we increase the drug survival time of biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(8):1585–1586. doi: 10.1111/ced.15232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(181):609–611. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ribero S, Ramondetta A, Fabbrocini G, et al. Effectiveness of Secukinumab in the treatment of moderate-severe hidradenitis suppurativa: results from an Italian multicentric retrospective study in a real-life setting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(35). doi: 10.1111/jdv.17178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marasca C, Megna M, Balato A, Balato N, Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G. Secukinumab and hidradenitis suppurativa: friends or foes? JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(2):184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thorlacius L, Theut Riis P, Jemec GBE. Severe hidradenitis suppurativa responding to treatment with secukinumab: a case report. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(1):182–185. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang CH, Huang IH, Tai CC, Chi CC. Biologics and small molecule inhibitors for treating hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2022;10(6):1303. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10061303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Frew JW. In search of therapeutic biomarkers to interleukin-23 antagonism in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(5):588–589. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zouboulis CC, Frew JW, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. Target molecules for future hidradenitis suppurativa treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(Suppl 1):8–17. doi: 10.1111/exd.14338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maarouf M, Clark AK, Lee DE, Shi VY. Targeted treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the current literature and ongoing clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(5):441–449. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1395806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]