Abstract

Radiotherapy is one of the cornerstone of the glioblastoma treatment paradigm. However, the resistance of tumor cells to radiation results in poor survival. The mechanism of radioresistance has not been fully elucidated. This study aimed to screen the differential expressed genes related with radiosensitivity. The differentially expressed genes were screened based on RNA sequencing in 15 pairs of primary and recurrent glioblastoma that have undergone radiotherapy. Candidate genes were validated in 226 primary and 134 recurrent glioblastoma (GBM) obtained from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) database. RNA and protein expression were verified by Quantitative Real-time PCR (qPCR) and western blot in irradiated GBM cell lines. The candidate gene was investigated to explore the relationship between mRNA levels and clinical characteristics in the CGGA and The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox regression analysis were used for survival analysis. Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analysis were used for bioinformatics analysis. Four genes (TMEM59L, Gelsolin, ZBTB7A and ATX) were screened. TMEM59L expression was significantly elevated in recurrent glioblastoma and lower in normal brain tissue. We selected TMEM59L as the target gene for further study. The increasing of TMEM59L expression induced by radiation was confirmed by mRNA and western blot in irradiated GBM cell. Further investigation revealed that high expression of TMEM59L was enriched in IDH mutant and MGMT methylated gliomas and associated with a better prognosis. Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analysis revealed that TMEM59L was closely related to the DNA damage repair and oxidative stress respond process. We speculated that the high expression of TMEM59L might enhance radiotherapy sensitivity by increasing ROS-induced DNA damage and inhibiting DNA damage repair process.

Keywords: radiotherapy, radiosensitive, glioblastoma, TMEM59L

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most prevalent and lethal tumor of the central nervous system [1, 2]. There is level 1 evidence that RT provided a clear survival benefit, which has been proved by numerous randomized controlled trials. Despite elevated radiation dose and the improvement of RT equipment, the survival of GBM has not been significantly improved over the past 30 years. The resistance to the cytotoxic effects of RT is increasingly recognized as a significant impediment to effective radiotherapy. Currently, the median survival of GBM is still <15 months [3]. It is urgently needed to identify reliable molecular targets and improve the effect of radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy potently induces massive cell death by triggering the activation of death signaling in cancer cells through direct or indirect DNA damage [4, 5]. However, a small portion of cancer cells may survive by activating compensatory survival signaling, involving damage-repair signaling and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging. Cancer cells that survived after radiotherapy may exhibit radioresistance and lead to rapid tumor recurrence within the radiation field, which was the most common clinical recurrence pattern. We assumed that the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after radiotherapy might be a key factor to elucidate the molecular mechanism of radioresistance.

Transmembrane protein 59-like (TMEM59L) is a newly identified brain-specific membrane-anchored protein that belongs to a large family of genes encoding transmembrane (TMEM) proteins [6, 7]. Many TMEMs function as channels to permit the transport of specific substances across the biological membrane and fulfill important physiological functions such as mediating cell chemotaxis, inflammatory signaling pathways, apoptosis, autophagy, etc. [8–12]. TMEM59 and its homolog TMEM59L do not have any known functional domains apart from the signal peptide and the TMEM domain. Both proteins have not yet been functionally described [13]. Recent studies have demonstrated that the downregulation of TMEM59L can protect neurons from oxidative stress [7].

In this study, we aim to investigate the function and expression characteristics of TMEM59L in GBM and radiotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples

RNA sequencing data from the 15 paired datasets and the validation dataset, consisting of 226 primary GBMs 134 recurrent GBMs, were obtained from Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) (http://www.cgga.org.cn/). As a control group, mRNA sequencing data from 20 cases non-glioma classes were downloaded from the CGGA database to compare the expression of TMEM59L in glioma and normal brain tissues. The RNA-sequencing data and corresponding clinical information, including age, gender, histology, pathological subtype, MGMT promoter methylation, IDH status and survival information were downloaded from the CGGA database and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov) as training cohort and validation cohort, respectively.

Cell culture

Three human GBM cell lines, including U87, U251 and LN229 purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank were applied to cytological experiments in vitro. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Humidified incubators were supplied with an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C.

Cell irradiation

Irradiation methods were as follows: Precision X-ray Irradiator (America) was used. Culture dishes were placed under a collimator at a source-to-surface distance of 50 cm, ensuring that the field size covered the culture dish, and the dose rate was 200 cGy/min. The total radiation dose was 36Gy, divided into three fractions of 12 Gy each, administered over three consecutive days.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted after irradiation using a total RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA intensity was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The expression levels of the target genes were analyzed using an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR System. Transcript levels of GAPDH were normalized. The relative mRNA expression levels of the target genes were calculated using the comparative CT method, and the following TMEM59L primer sequences were used:

Forward, 5′- AGT CTC CCT ATG ACA GAG CCG −3′,

Reverse, 5′- GCT TCA CAC TCA GTT TGG GTG −3′.

The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primer sequences were used:

Forward, 5′- UGACCUCAACUACAUGGUUTT −3′.

Reverse, −5′- AACCAUGUAGUUGAGGUCATT −3′.

Western blot analysis

In this study, the following antibodies were used:

Rabbit anti-TMEM59L monoclonal antibody (1500, ab250825,abcam).

Mouse anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (13 000, ab8245,abcam).

Total protein was extracted from cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The protein concentration was measured using Coomassie Brilliant Blue (APPLYGEN A1011). In total, 30 μg protein was subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Cat. No. IPVH00010; EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk (BD Biosciences) in a shaker at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibodies were mixed into the milk according to the manufacturer’s specifications, and this milk was added to the membranes and kept overnight at 4°C. After washing the membrane three times for 10 min each, secondary antibodies were added, and the membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. This experiment was repeated three times. The results were analyzed using an enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Bioinformatics analysis

The correlationship between TMEM59L mRNA expression and other genes was verified by Pearson’s correlation analysis (|R| > 0.5, P < 0.05) and was selected for analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to investigate the biological processes closely associated with TMEM59L expression in the CGGA and TCGA sequencing datasets. Genes that showed significant correlation with TMEM59L expression (Pearson |R| > 0.4, P < 0.05) in the CGGA and (Pearson |R| > 0.5, P < 0.05) TCGA were used for KEGG pathway and Gene ontology analysis with DAVID [14].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 16.0 software, the R programming language 3.2.5 and the Graph Pad Prism 7.0 software. Student’s t-test was used to compare the expression of TMEM59L in normal brain and glioma tissues, the differential expression after radiotherapy and the different expression levels between grades or subtypes. The prognostic significance was assessed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and univariate as well as multivariate Cox regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TMEM59L expression is increased in recurrent GBM and irradiated GBM cells

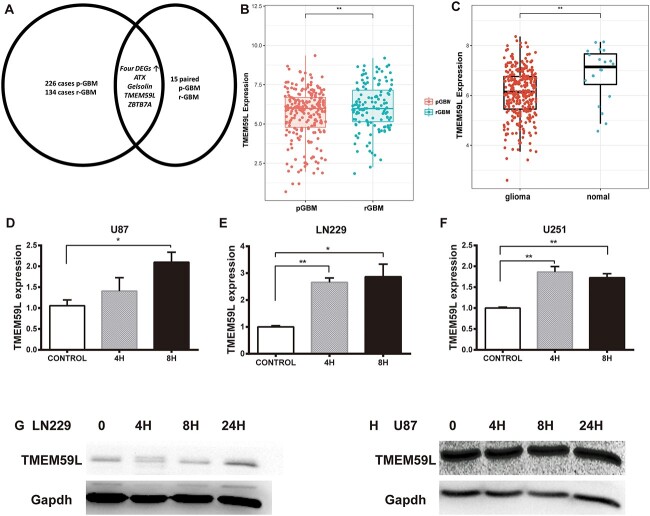

Student’s t-test was performed on the 15 paired data and CGGA database to identify DEGs after radiotherapy. We next validated the candidate genes in 226 primary and 134 recurrent GBM obtained from CGGA database (Fig. 1A). During the screening process, we found four DEGs after RT, including TMEM59L, Gelsolin,ZBTB7A and ATX. The screening process is shown in Fig. 1A. TMEM59L expression was significantly elevated both in the paired data (P = 0.04) and validation dataset (P < 0.001) and was selected as the target gene for this study (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig. 1.

TMEM59L expression is increased in recurrent GBM and irradiated GBM cells. (A) As shown in the screening process, four DEGs including TMEM59L, Gelsolin, ZBTB7A and ATX were upregulated in recurrent GBM. (B) The expression levels of TMEM59L were analyzed in 15 paired pGBM and rGBM of the CGGA mRNA Sequencing datasets. (C) The upregulation of TMEM59L in recurrent GBM was verified in 226 primary and 134 recurrent sample of the CGGA mRNA sequencing datasets. The RNA expression of TMEM59L is increased in (D) U87 cell line, (E) LN229 cell line and (F) U251 cell line after radiation. The protein expression of TMEM59L increased in (G) LN229 and (H) U87 cell lines after irradiation. pGBM = primary GBM, rGBM = recurrent GBM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

We also analyzed the expression of TMEM59L in normal brain and glioma tissue using CGGA non-glioma mRNA sequencing data. The results showed that the expression of TMEM59L in glioma was significantly lower than that in normal brain tissue (Supplemental Fig. 1). To determine the relationship between TMEM59L expression and RT, we measured TMEM59L mRNA and protein expression in irradiated GBM cell lines. The expression of TMEM59L was analyzed by qPCR (U87, U251, and LN229) and western blot (U87 and LN229) at 0, 4 and 8 h after radiation, respectively. The results showed that TMEM59L expression was significantly upregulated (Fig. 1D–H).

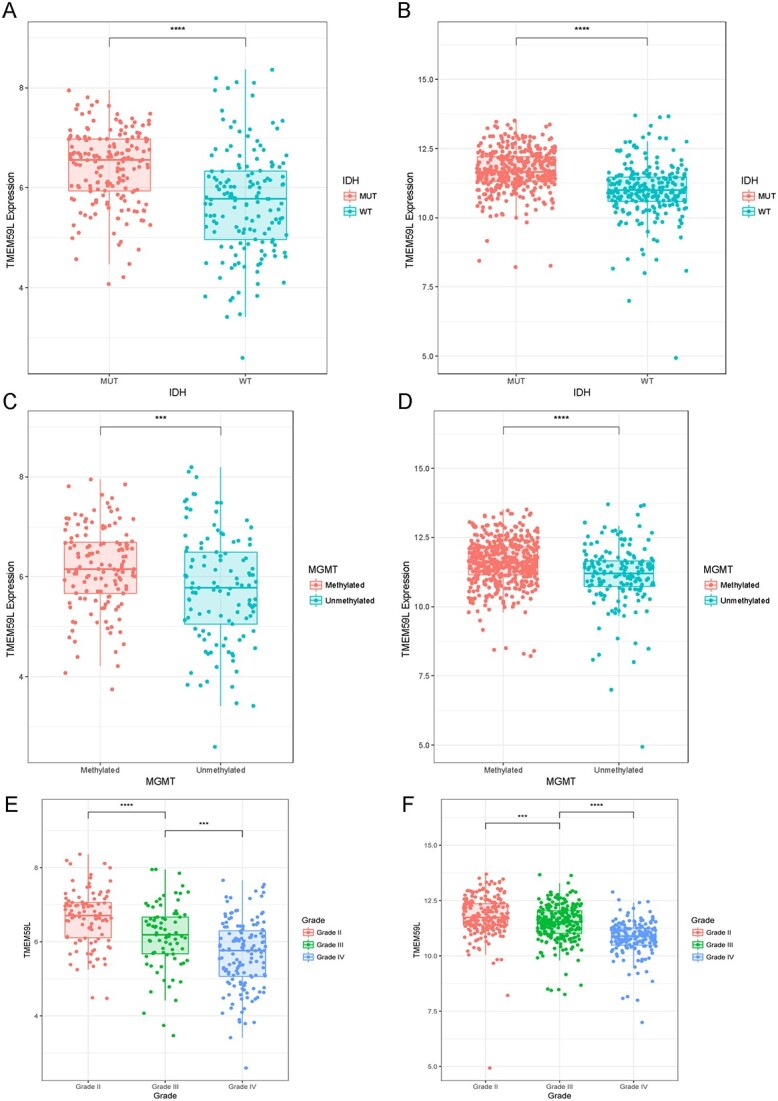

TMEM59L expression level shows a subtype preference

Next, we invested the clinical prognostic significance of the TMEM59L in glioma. The high-expression of TMEM59L was enriched in IDH mutant and MGMT methylated glioma (Table 1, Fig. 2A–D). MGMT methylation is considered as an important biomarker to determine whether patients benefit from chemotherapy. To determine the effect of chemotherapy on TMEM59L expression, we compared the TMEM59L expression between patients who received chemotherapy or those who did not (Supplemental Fig. 2). The results showed that the expression of TMEM59L was lower in patients who received chemotherapy. In addition, the TMEM59L expression level was negatively correlated with tumor grade (Fig. 2E and F) and significantly upregulated in the favorable neural subtype [15, 16]. The ROC curves showed that the area under the curve was up to 80.2 and 89.6% in the CGGA and TCGA sequencing dataset, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients with glioma in CGGA and TCGA stratified by TMEM59L level

| TCGA (699) | CGGA (325) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Low (349) | High (350) | Low (162) | High (163) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 192 | 176 | 106 | 97 |

| Female | 135 | 133 | 56 | 66 |

| NA | 22 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤40 | 101 | 145 | 57 | 86 |

| >40 | 226 | 164 | 105 | 77 |

| Na | 22 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade | ||||

| 2 | 76 | 147 | 27 | 76 |

| 3 | 110 | 135 | 36 | 43 |

| 4 | 141 | 27 | 99 | 44 |

| Na | 22 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| IDH mutation | ||||

| Mutant | 158 | 285 | 62 | 114 |

| Wild type | 184 | 62 | 100 | 49 |

| NA | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| MGMT-status | ||||

| Methylated | 209 | 283 | 66 | 73 |

| Unmethylated | 109 | 59 | 75 | 42 |

| NA | 31 | 8 | 21 | 48 |

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneity of TMEM59L expression in glioma. (A, C) TMEM59L expression with different IDH status in CGGA and TCGA databases. (B, D) TMEM59L expression according to MGMT status in CGGA and TCGA databases. (E–F) TMEM59L expression in different grades in CGGA (left) and TCGA (right) databases. ****P < 0.001, ***P < 0.05.

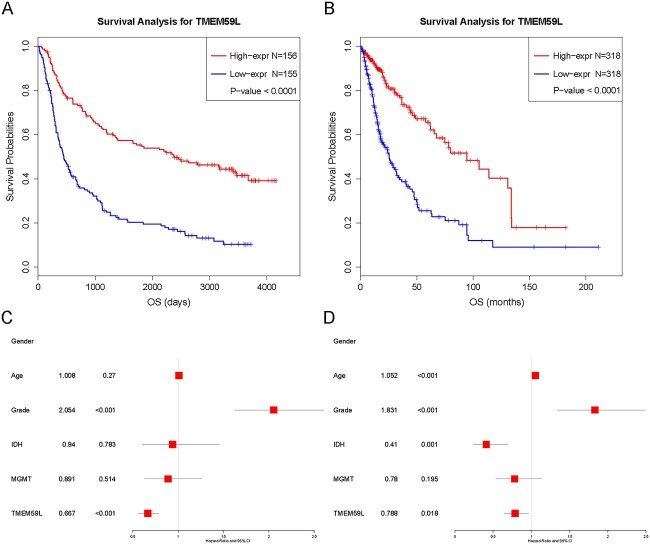

The high expression of TMEM59L was associated with a better prognosis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed to determine the prognosis value and evaluate the association between TMEM59L expression and survival in glioma patients. TMEM59L expression level was divided into low/high groups according to the median value of TMEM59L mRNA expression in 325 patients from the CGGA dataset. The results showed that high expression of TMEM59L was related to longer overall survival than low expression in the CGGA dataset (Fig. 3A and C). Since IDH mutant and MGMT subtypes are commonly considered as two subtypes correlated with better therapeutic outcomes in glioma patients, we performed further survival analysis according to IDH mutation and MGMT methylation status using the CGGA database. Consistent with the above results, high expression of TMEM59L was associated with a better prognosis in the two subgroups (Supplemental Fig. 4). Multivariate Cox analyses showed that TMEM59L expression (HR: 0.667, 95% CI: 0.56–0.79, P <0.001) was an independent predictor of longer survival (Fig. 3A and C). Similar results were validated in a cohort of 699 patients from the TCGA dataset (Fig. 3B and D). The results suggested that TMEM59L might be a novel independent prognostic biomarker for glioma and GBM patients.

Fig. 3.

The survival analysis in glioma from the CGGA and TCGA databases according to TMEM59L expression. (A, B) Kaplan–Meier curves of glioma survival based on the expression level of CGGA and TCGA database fenbied. (C, D) Forest plot in CGGA and TCGA dataset.

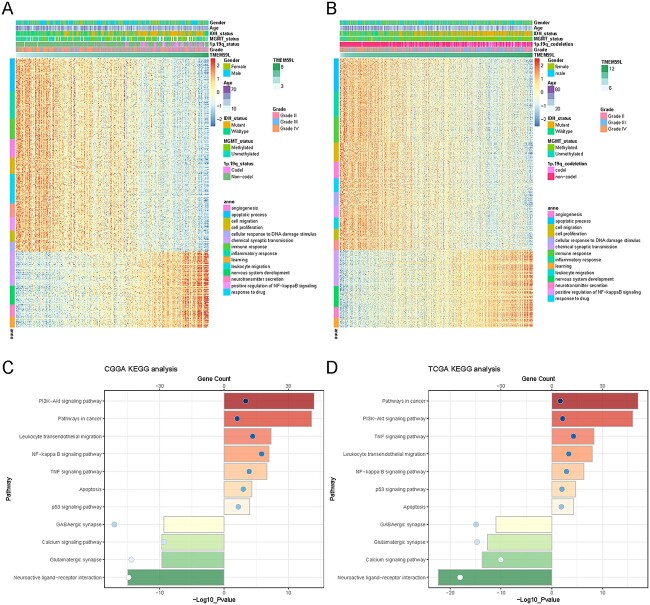

TMEM59L-related biological process

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to investigate the biological process tightly associated with TMEM59L expression as well as several classical immune checkpoints and Glioma stem cells-related genes in the CGGA and TCGA sequencing datasets. It is shown that the negative correlation genes with TMEM59L expression are highly enriched in the immune and inflammatory response, cell proliferation and migration, apoptosis process, response to drug and DNA damage. The positive correlation genes tended to be enriched in biological processes that are normal and indispensable, such as neurotransmitter secretion and nervous system development. In addition, TMEM59L expression was negatively related to CD44, STAT3, IL6 and FUT4 and positively related to L1CAM (Supplemental Fig. 5). TMEM59L expression was tightly related to the PD1 family, B7 family, LAG3, TIM3, CTIL4 and IDO in the context of the immune system. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the negatively related genes with TMEM59L expression were enriched in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, the NF-kappa B (NF-κB), P53 signaling pathway, and the positively related genes were enriched in the GABAergic synapse, Glutamatergic synapse. The two datasets shared all the results mentioned above (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Biological function and pathway analysis in CGGA and TCGA datasets. (A, B) Gene ontology analysis of TMEM59L expression in glioma. The samples were ranked according to TMEM59L expression from low to high. The high expression of TMEM59L was enriched in IDH mutant, MGMT methylated, 1p/19q co-deletion glioma and was negatively correlated with tumor grade. (C, D) KEGG analysis of TMEM59L expression in glioma. The bar charts represented the count and the circle represented the P-value. The color also represented the count.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified and verified the increased expression of TMEM59L after radiotherapy through a public database and in vitro experiment. Our results show that the expression of TMEM59L is higher in glioma tissue compared to normal brain tissue. Importantly, the TMEM59L expression showed great value in the prognosis of glioma patients. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that TMEM59L was closely related to the DNA damage and repair process. Through these results, we may infer that the high expression of TMEM59L might enhance tumor radiosensitivity. These findings provide an important reference for the study of GBM radiosensitivity.

The expression of TMEM59L showed predictive value for prognosis in glioma and GBM. It is well established that radiation executes anti-tumor DNA damaging effects through direct or indirect DNA damage. About two-thirds of DNA damage attributed to radiotherapy is caused by indirect effects via the generation of ROS. Interestingly, high expression of TMEM59L is concentrated in IDH mutation-type glioma. Previous studies have reported that the IDH1 mutation makes cells more vulnerable to radiation [17, 18]. Several studies have highlighted the important role of IDH in defense against radiation-induced oxidative injury [19]. The IDH mutation can change the metabolic state of the cell and increase the oxidation of NADPH, rendering the affected GBM cells more vulnerable to ROS induced by irradiation. Recent studies have demonstrated that TMEM59L can mediate oxidative stress-induced cell death through autophagy and apoptosis pathway. Downregulation of TMEM59L protects neurons against oxidative stress [7]. These results indicated that the high expression of TMEM59L might increase radiosensitivity by downregulating ROS scavenging and increasing oxidative damage of tumor cells [20, 21]. In addition, the correlation analysis displayed TMEM59L showing well consistency in two GCS markers related with radiosensitivity. TMEM59L expression was negatively related to CD44, which has been reported as radioresistance markers and positively related with L1CAM, which is inversely correlated with radioresistance.

Radiation-induced damages could also trigger a large network of intracellular signaling events. Multiple studies have reported that overactivation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway after RT is closely related to tumor radioresistance. The activation of NF-κB and mTOR could promote cell survival by enhancing the DDR and mediating autophagy and apoptosis [22, 23]. Several studies have proven that targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway by specific repressors in association with radiation appears to enhance radiosensitization [24, 25]. NF-κB was found to be activated and associated with a higher grade of astrocytic tumors [26]. The activation of NF-κB could occur in response to DNA damaging agents and provoke multiple radioresistance signals, which attenuate the lethal effects of radiation. Inhibition of NF-κB was proved to be an effective strategy to enhance tumor radiosensitivity [27, 28]. It can be inferred that TMEM59L might enhance radiosensitivity by inhibiting PI3K/AKT and NF-κB activation.

Regarding the immune system, the expression of immune checkpoint molecules in the tumor microenvironment can affect the efficiency of the immune response. Evidence accumulated over recent years has revealed that exposure of cancer cells to radiation may cause upregulation of PD-L1, leading to resistance to radiotherapy. Abrogation of both CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways has been associated with higher radiosensitivity [29]. Our result displayed a negative correlation between TMEM59L and immune checkpoints, suggesting that that upregulated TMEM59L expression might be important in maintaining immune response activity.

CONCLUSION

The increased expression of TMEM59L after irradiation might enhance radiosensitivity by increasing ROS-induced DNA damage and inhibiting DNA damage repair. However, the specific mechanism is still unclear. Further research may help delineate processes that contribute to the radiosensitive and improve the efficacy of radiotherapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the grants from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 82001778, 82003192).

PRESENTATION AT A CONFERENCE

Not applicable.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Dezhi Gao, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Gamma-Knife Center, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

Peng Wang, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Radiation Oncology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

Lin Zhi, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Radiation Oncology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

Shibin Sun, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Gamma-Knife Center, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

Xiaoguang Qiu, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Radiation Oncology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

Yanwei Liu, Department of Molecular Neuropathology, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China; Department of Radiation Oncology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 119 South Fourth Ring West Road, Fengtai District, Beijing 100070, China.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jiang T, Mao Y, Ma W et al. Chinese glioma cooperative group (CGCG) CGCG clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult diffuse gliomas. Cancer Lett 2016;375:263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med 2008;359:492–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fine HA. Bevacizumab in glioblastoma - still much to learn. New Engl J Med 2014;370:764–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schafer N, Gielen GH, Rauschenbach L et al. Longitudinal heterogeneity in glioblastoma: moving targets in recurrent versus primary tumors. J Transl Med 2019;17:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim J, Lee IH, Cho HJ et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of the primary glioblastoma genome. Cancer Cell 2015;28:318–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vinothkumar KR, Henderson R. Structures of membrane proteins. Q Rev Biophys 2010;43:65–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zheng Q, Zheng X, Zhang L et al. The neuron-specific protein TMEM59L mediates oxidative stress-induced cell death. Mol Neurobiol 2017;54:4189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayez A, Malaisse J, Roegiers E et al. High TMEM45A expression is correlated to epidermal keratinization. Exp Dermatol 2014;23:339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas-Gatewood C, Neeb ZP, Bulley S et al. TMEM16A channels generate ca(2)(+)-activated cl(−) currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;301:H1819–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foulquier F, Amyere M, Jaeken J et al. TMEM165 deficiency causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malhotra K, Luehrsen KR, Costello LL et al. Identification of differentially expressed mRNAs in human fetal liver across gestation. Nucleic Acids Res 1999;27:839–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang KY, Huang RY, Tong XZ et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of TMEM71 expression at the transcriptional level in glioma. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019;25:965–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elson GCA, de Coignac AB, Aubry JP et al. BSMAP, a novel protein expressed specifically in the brain whose gene is localized on chromosome 19p12. Biochem Bioph Res Co 1999;264:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu HM, Wang Z, Li MY et al. Gene expression and methylation analyses suggest DCTD as a prognostic factor in malignant glioma. Sci Rep 2017;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin N, Yan W, Gao KM et al. Prevalence and clinicopathologic characteristics of the molecular subtypes in malignant glioma: a multi-institutional analysis of 941 cases. PLoS One 2014;9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhat KPL, Balasubramaniyan V, Vaillant B et al. Mesenchymal differentiation mediated by NF-kappa B promotes radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2013;24:331–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li SC, Chou AP, Chen WD et al. Overexpression of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutant proteins renders glioma cells more sensitive to radiation. Neurooncology 2013;15:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juratli TA, Lautenschlager T, Geiger KD et al. Radio-chemotherapy improves survival in IDH-mutant, 1p/19q non-codeleted secondary high-grade astrocytoma patients. J Neuro Oncol 2015;124:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ying WH. NAD(+)/ NADH and NADP(+)/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Sign 2008;10:179–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molenaar RJ, Botman D, Smits MA et al. Radioprotection of IDH1-mutated cancer cells by the IDH1-mutant inhibitor AGI-5198. Cancer Res 2015;75:4790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rivera AL, Pelloski CE, Gilbert MR et al. MGMT promoter methylation is predictive of response to radiotherapy and prognostic in the absence of adjuvant alkylating chemotherapy for glioblastoma (vol 12, pg 116, 2010). Neuro Oncol 2010;12:617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Naderali E, Valipour B, Khaki AA et al. Positive effects of PI3K/Akt Signaling inhibition on PTEN and P53 in prevention of acute lymphoblastic Leukemia tumor cells. Adv Pharm Bull 2019;9:470–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Price JM, Prabhakaran A, West CML. Predicting tumour radiosensitivity to deliver precision radiotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023;20:83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xia S, Zhao Y, Yu SY, Zhang M. Activated PI3K/Akt/COX-2 pathway induces resistance to radiation in human cervical cancer HeLa cells. Cancer Biother Radio 2010;25:317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang L, Graham PH, Ni J et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in the treatment of prostate cancer radioresistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;96:507–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS Jr. TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science 1996;274:784–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Didelot C, Barberi-Heyob M, Bianchi A et al. Constitutive NF-kappa B activity influences basal apoptosis and radiosensitivity of head-and-neck carcinoma cell lines. Int J Radiat Oncol 2001;51:1354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang CR, Wilson-Van Patten C, Planchon SM et al. Coordinate modulation of Sp1, NF-kappa B, and p53 in confluent human malignant melanoma cells after ionizing radiation. FASEB J 2000;14:379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res 2014;74:5458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.