Abstract

Background:

Repetitive negative thinking (RNT) is a frequent symptom of depression (MDD) associated to poor outcomes and treatment resistance. While most studies on RNT have focused on structural and functional characteristics of gray matter, this study aimed to examine the association between white matter (WM) tracts and interindividual variability in RNT.

Methods:

A probabilistic tractography approach was used to characterize differences in the size and anatomical trajectory of WM fibers traversing psychosurgery targets historically useful in the treatment of MDD (anterior capsulotomy, anterior cingulotomy, and subcaudate tractotomy), in patients with MDD and low (n = 53) or high RNT (n = 52), and healthy controls (HC, n = 54). MDD samples were propensity matched on depression and anxiety severity and demography.

Results:

WM tracts traversing left-hemisphere targets and reaching the ventral anterior body of the corpus callosum (thus extending to contralateral regions) were larger in MDD and high RNT compared to low RNT (effect size D = 0.27, p = 0.042) and HC (D = 0.23, p = 0.02). MDD was associated to greater size of tracts that converge onto the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, regardless of RNT intensity. Other RNT-nonspecific findings in MDD involved tracts reaching the left primary motor and the right primary somatosensory cortices.

Conclusions:

This study provides the first evidence that WM connectivity patterns, which could become targets of intervention, differ between high- and low-RNT MDD participants. These WM differences extend to circuits that are not specific to RNT, possibly subserving reward mechanisms and psychomotor activity.

Keywords: Depression, repetitive negative thinking, white matter tracts, probabilistic tractography, psychosurgery, diffusion tensor imaging

INTRODUCTION

Remission rates achieved by first-line treatments in Major Depression (MDD) are unsatisfactory. Lack of meaningful improvement affects a third of all patients after four consecutive, adequate treatment attempts (1,2), resulting in persistent residual symptoms and functional disability after assertive antidepressant treatment (3). Converging lines of evidence suggest that Repetitive Negative Thinking (RNT; often referred to as rumination in the depression literature, but demonstrated to be a largely transdiagnostic clinical phenomenon (4)) might account for a substantial disease burden in MDD. First, RNT, defined as negative, repetitive, and uncontrollable thoughts that are intrusive and difficult to disengage from (4), is itself associated with a series of adverse prognostic outcomes in affective disorders that overlap with treatment resistance in MDD, namely residual symptoms after treatment response, higher rate of recurrences, greater functional compromise, and suicide (5–7). Second, one of the most consistent neurobiological findings in treatment resistant MDD has been the presence of functional abnormalities in the Default Mode Network (DMN)(8,9). Such alterations have been frequently hypothesized to underlie rumination in MDD (9,10) given the role of DMN in self-referential mentation in general (8). In fact, given that dysfunction of DMN nodes and edges are a feature of treatment resistant MDD, it has been proposed that RNT needs to be explored as a potential major behavioral mediator of this clinical phenomenon (9).

Studies that searched for functional and structural correlates of treatment resistance in MDD have nonetheless resulted in inconsistent findings (9–15). These inconclusive results are unfortunate, because the detection of abnormal patterns of white matter (WM) tract disposition associated with treatment resistance and RNT in MDD would help to define neural targets for effective neuromodulation. In fact, specific engagement of WM tracts has been observed to be necessary for therapeutic response to neuromodulation in other settings (16,17). For example, whereas there is a paucity of studies specifically focusing in ablative procedures, it has been proposed that beneficial effects of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in MDD show some degree of symptom specificity, namely subgenual cingulate DBS mostly ameliorating helplessness and anhedonia, and DBS of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum helping with motivation and psychomotor energy (18). To the extent of our knowledge, effects of psychosurgical procedures on RNT in MDD have not been specifically measured. In the case of RNT, specific definition of underlying brain mechanisms of clinical significance can be difficult for diverse reasons. First, patients with more intense RNT tend to have more severe MDD, and this overlap makes it challenging to parse the neural mechanisms specific to RNT in MDD, as separate from other symptoms. Second, whereas an “agnostic,” data-driven whole-brain search for WM tracts associated with RNT intensity may have some advantages, including unbiased search for disease mechanisms, it might be difficult to immediately infer the therapeutic meaning of any detected differences, as these could be epiphenomenal and not necessarily relevant to clinical management. To address these problems, in this study we 1) used a propensity scoring to discern the specific contribution of RNT, independent from MDD severity and demographic characteristics that could correlate with it, and 2) specifically focused on WM tracts traversing historical psychosurgical targets that have long been used in treatment-resistant MDD, and presumably due their effectiveness to engaging large-scale brain circuits involved in MDD pathogenesis.

The propensity score is defined as the probability of assigning a vector of observed covariates to a particular group (19,20). By applying propensity score matching, it was possible to control for the fact that RNT might covary with a series of sample characteristics (especially depressive symptom severity, but also anxiety, age, sex, education, ethnicity, and income), and in this way we controlled for these biases in a quasi-experimental design, comparing individuals with MDD who differ in the intensity of RNT but are similar in clinical and demographic characteristics, and healthy subjects (21,22). In addition -as previously stated- hypothesizing that effective approaches to treatment-resistant MDD would exert their effect at least in part by targeting and ameliorating RNT, we specifically focused on WM tracts traversing simulated lesions of anterior capsulotomy (ACtx), anterior cingulotomy (ACgtx), and subcaudate tractotomy (SCT; Figure 1)(23–26). In this work, we performed probabilistic tractography (27) to delineate reconstructed WM fiber trajectories by processing diffusion MRI (dMRI) data, and obtaining metrics of size and geometry of WM fibers traversing the simulated psychosurgical lesions. We hypothesized that, if the prediction of the present study and others (9) that treatment resistance in MDD is in part explained by RNT were correct, then those converging WM pathways could conceivably be related to the intensity of RNT in MDD as well. Moreover, we hypothesized that such surgical procedures are useful because they affect WM pathways that participate in MDD symptom formation (24) and are thus responsible for their beneficial effects.

Figure 1:

Anatomical location of studied psychosurgical targets. All simulated targets were 10mm-diameter spheres over a T1 template built with all subject groups. ACtx: anterior capsulotomy; ACgtx: anterior cingulotomy; SCT: subcaudate tractotomy.

Methods and Materials

Participants

In this study we examined a propensity-matched sample consisting of 158 subjects with MDD and healthy controls (HC) from the Neuroscience-Based Mental Health Assessment and Prediction (NeuroMAP, P20GM121312) – Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (CoBRE) at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research (LIBR) (28). The MDD and HC diagnoses were based on an abbreviated version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI V.6.0 or 7.0) (29), followed by a clinical case conference by a board-certified psychiatrist. The study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Our final propensity matched sample included 52 High-RNT, 53 Low-RNT and 54 HC with both MRI acquisition (DWI and T1-weigthed images) required for this study. In Supplemental Material we present details of the propensity matched sample, and MRI data acquisition parameters.

T1 Images Processing

T1 images were processed as described in detail in the Supplement, employing the Desikan-Killiany atlas (33), and following guidelines of a previous report for the placement of spheres simulating the psychosurgical lesions (24).

Tractography Processing

Details of the preprocessing of diffusion images are provided in the Supplemental Material. After preprocessing, to reconstruct the WM tracts, and employing MRtrix3 software (30) we applied a default probabilistic algorithm, Second-Order Integration over Fiber Orientation Distributions (iFOD2) in a whole-brain tractography approach (30–32). Once a tractogram per subject was generated, we selected those streamlines that traversed at least one of three historical psychosurgical targets long known to be efficacious in the treatment of MDD, namely ACgtx, ACtx, and SCT (Figure 1; see T1 Images Processing in the Supplement section for details). This analysis was made for each hemisphere, thus obtaining six subtractograms for each participant (3 simulated ablation lesions × 2 hemispheres). To observe the specificity of any surgical target-related abnormalities, we also explored WM tracts connecting the right superior temporal sulcus with the ipsilateral anterior insular cortex, observed to display greater connectivity in relation to the intensity of RNT in a similar sample (22).

From Tractograms to Voxels in WM parcels

Once a sub-tractogram per hemisphere was obtained for each subject, we transformed it to a streamline-mapped image, containing colored voxels with at least one streamline. Then, this streamline-mapped image was binarized (i.e. containing any streamlines or containing no streamlines in each voxel). Finally, every binary map was multiplied by each of the 75 WM-parcel masks. Therefore, the outcome of the last step was a binary image of each WM-parcel mask, with voxels whose intensity were equal to one (if there was at least one streamline that traversed at least one psychosurgical target), or zero (if no streamlines were generated in a voxel). We used these outcomes to define 1) the number of voxels with intensity equal to one within a WM-parcel mask and 2) the mass center of voxels counted in 1), as described in detail in Supplemental information.

Statistical Analysis

A Kruskal-Wallis (KW) procedure (implemented in Matlab R2022a) was employed to test inter-group differences, followed by a post hoc Fisher’s LSD test. A Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare specifically the two groups of MDD participants. We also report raw FDR (34,35) p values (pFDR). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test was used to estimate the effect size (D) of independent variables on the target variables.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the three groups, confirming adequate score propensity matching.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Propensity Score-Matched Samples.

| HC | Low-RNT | High-RNT | Statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 54) | (n = 53) | (n = 52) | |||

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 27.28 (8.46) | 28.62 (8.11) | 27.08 (7.61) | F = 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Female (%) | 48 (89) | 42 (79) | 42 (80) | X2 = 2.04 | 0.36 |

| Race/Ethnicity: Non-White (%) | 25 (45) | 25 (47) | 17 (33) | X2 = 2.83 | 0.24 |

| Asian | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | ||

| Black | 6 (11) | 8 (15) | 2 (4) | ||

| Hispanic | 8 (15) | 8 (15) | 1 (2) | ||

| Native American | 1 (2) | 7 (13) | 8 (15) | ||

| Other | 6 (9) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | ||

| White | 29 (55) | 28 (53) | 35 (67) | ||

| Annual Income (dollars) | 74189 (14892) | 56199 (36652) | 65494 (53747) | F = 1.60 | 0.21 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.88 (5.11) | 26.28 (4.90) | 28.04 (6.02) | F = 4.70 | 0.01 * |

| HAM-D | 1.96 (2.10) | 14.18 (4.34) | 14.05 (4.68) | F = 167 | < 0.001 * |

| PHQ-9 | 0.96 (1.63) | 12.05 (4.80) | 13.56 (4.79) | F = 157 | < 0.001 * |

| OASIS | 1.03 (1.43) | 9.87 (2.40) | 10.28 (4.05) | F = 182 | < 0.001 * |

| RRS | 30.83 (9.55) | 48.42 (8.01) | 69.41 (7.30) | F = 290 | < 0.001 ** |

| SDS | 0.31 (0.65) | 4.36 (1.74) | 5.63 (2.15) | F = 155.3 | <0.001** |

| Psychotropic Medication (%) | – | 11 (21) | 8 (15) | X2 = 0.22 | 0.64 |

| First Depressive Episode | – | 15 (28) | 11 (21) | X2 = 0.52 | 0.45 |

BMI: Body Mass Index; HC: Healthy Controls; Low-RNT: MDD participants with RRS < 59; High-RNT: MDD participants with RRS score ≥ 59 HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; OASIS: Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; RRS: Ruminative Response Scale score. SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale. No participants had prior psychiatric inpatient admissions

: Low-RNT and High-RNT different from HC.

: all groups different from each other.

Number of Voxels Analysis

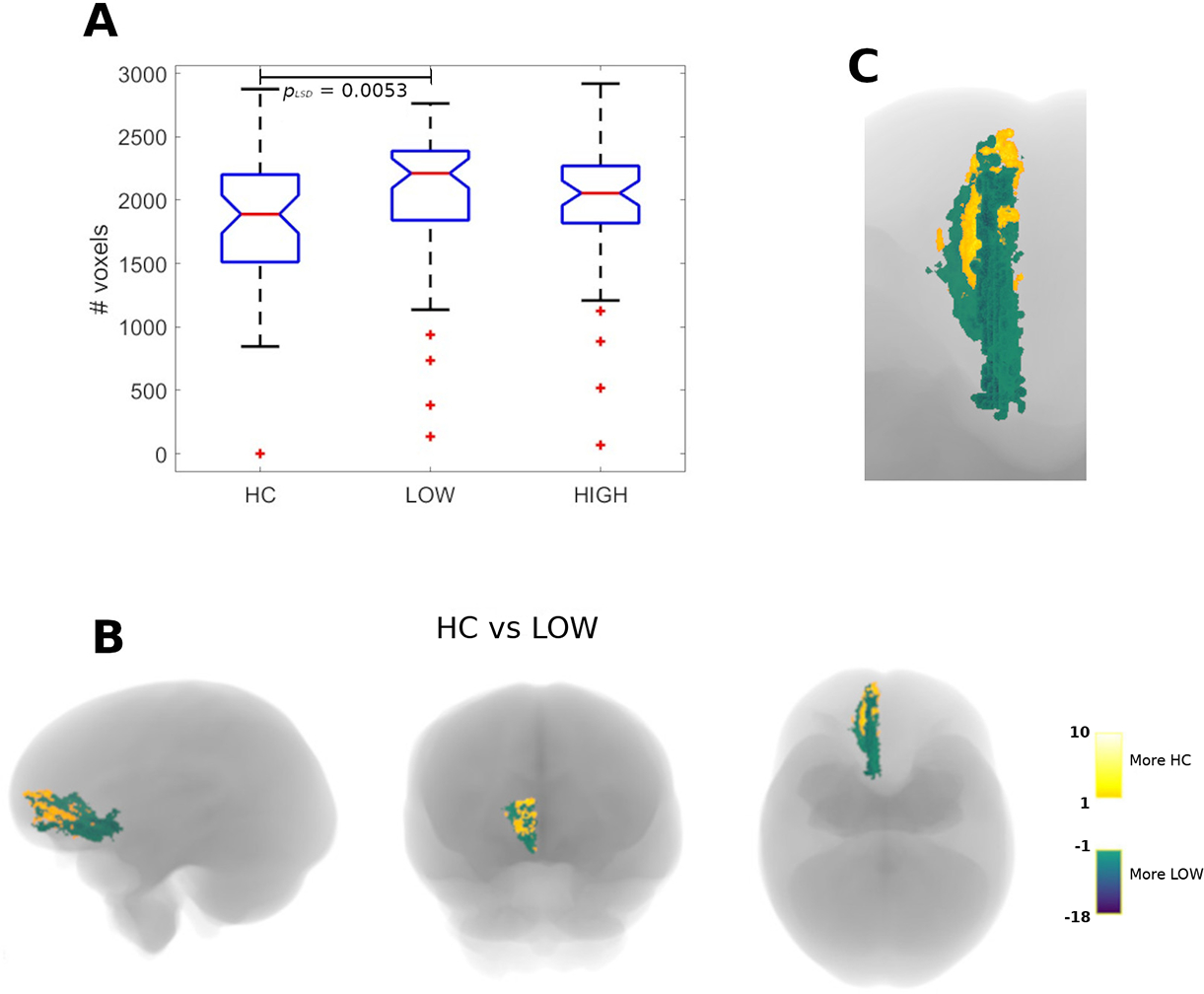

There were significant group differences in the number of voxels containing streamlines traversing left-sided surgical targets and involving the ventral anterior body of the corpus callosum (vabCC; Figure 2, panel A). High-RNT MDD had significantly more voxels containing streamlines than both Low-RNT MDD (effect size D = 0.27) and HC (effect size D = 0.23) (Figure 2, Panel A). Panels B and C show the regional distribution of excess vabCC fibers in three groups in the CC. High-RNT MDD participants had larger WM tracts traversing left hemisphere simulated surgical targets and reaching the right cuneus (uncorrected pMW = 0.046; not shown).

Figure 2:

Number of voxels containing streamlines originated in left-hemisphere psychosurgical targets and traversing the anterior body of the corpus callosum. Shown are the total number of voxels for the three groups (panel A) and the actual anatomical distribution of voxels in the intergroup comparison, both in the whole brain (panel B) and in a detailed sagittal view of the corpus callosum (panel C). Excess fibers in high-RNT MDD patients mainly involve the ventral portion of the anterior body of the corpus callosum (vabCC). pLSD denotes a Fisher’s LSD (pLSD) post-hoc procedure applied after a Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

There were significant intergroup differences in the number of voxels containing streamlines traversing surgical targets in either left (Figure 3, panel A) or right (Figure 4, panel A) hemispheres, and reaching the right medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC). Both MDD groups showed larger WM tracts reaching this cortical region compared to HC. Figures 3 and 4 also show the anatomical location of tract destinations in the three groups (panels B and C).

Figure 3:

Number of voxels containing streamlines originated in the left-hemisphere psychosurgical targets and converging onto the contralateral, right medial orbitofrontal cortex (r-mOFC) and part of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Shown are the total number of voxels for the three groups (panel A), and the actual anatomical distribution of voxels in the comparison between healthy controls (yellow) and MDD participants with low RNT (green), both in the whole brain (panel B) and in a detailed axial view of the r-mOFC. pLSD denotes a Fisher’s LSD (pLSD) post-hoc procedure applied after a Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

Figure 4:

Number of voxels containing streamlines originated in the right-hemisphere psychosurgical targets and converging onto the ipsilateral, right medial orbitofrontal cortex (r-mOFC) and part of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Shown are the total number of voxels for the three groups (panel A), and the actual anatomical distribution of voxels in the comparison between healthy controls (yellow) and MDD participants with either low (green) or high (blue) RNT, both in the whole brain (panel B) and in a detailed axial view of the r-mOFC. Please see the text for details. pLSD denotes a Fisher’s LSD (pLSD) post-hoc procedure applied after a Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

There were intergroup differences in size for WM tracts involving surgical targets in the left hemisphere and reaching ipsilateral precentral (primary motor) cortex (Figure 5, panel A). HC displayed larger WM tracts than both High-RNT and Low-RNT MDD groups. Panels B and C show the destination of fibers in the three groups within the precentral gyrus.

Figure 5:

Excess fibers traversing left-hemisphere psychosurgical targets and reaching the ipsilateral primary motor cortex. Panel A shows the intergroup comparisons. Shown also are the anatomical distribution of excess fibers for healthy controls (yellow) or either low (green) or high (blue) RNT MDD participants, both in a whole-brain location (panel B) and in a detailed axial view of the left primary motor cortex (panel C). pLSD denotes a Fisher’s LSD (pLSD) post-hoc procedure applied after a Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

Supplemental Figure 2 shows intergroup differences involving WM tracts reaching left middle frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and superior frontal gyrus.

Mass Center Coordinates Analysis

Supplemental Tables 1 to 3 show uncorrected quantitative intergroup differences in anatomical trajectories as assessed by mass center coordinate comparisons in axes x, y, and z in specific WM trajectories. Tracts traversing psychosurgical targets and reaching diverse regions of the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, cuneus, and insula showed intergroup differences in at least one spatial dimension (Supplemental Table). The only projections exhibiting significant intergroup differences in all three space axes involved WM tracts originating in left hemisphere simulated lesions, and reaching the contralateral postcentral gyrus (right primary somatosensory cortex). These differences remained significant (p < 0.05) after FDR correction. Post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences between HC and both Low-RNT (pLSD = 0.016) and High-RNT (pLSD = 0.00007) groups.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to quantify differences between individuals with MDD and either high or low RNT, compared with HC, in WM tracts that pass through surgical targets which have been previously shown to be useful in the management of treatment resistant MDD (ACtx, ACgtx, SCT). The main findings are that 1) MDD patients with more intense RNT have larger WM tracts originated in left hemisphere simulated surgical targets that traverse the vabCC (i.e., reaching contralateral, right hemisphere tissue destinations), as compared with both MDD patients with lower RNT and healthy controls; 2) WM projections traversing surgical targets in both hemispheres and converging onto the right mOFC are larger in patients with MDD than in healthy controls, regardless of the intensity of RNT; and 3) WM tracts traversing left-sided targets and involving the left primary motor cortex, are smaller in MDD patients compared with healthy controls, again with no influence of RNT. Other potentially relevant findings include smaller tracts originating from left-sided targets and involving ipsilateral mid-frontal gyrus (in its caudal portion) and PCC in patients with MDD compared to controls. Last, intergroup differences in WM fiber anatomical trajectories include different prefrontal regions, anterior cingulate cortex, left postcentral gyrus and temporal pole, and left insula (Supplemental Tables 1 to 3), although only WM tracts originated in the left hemisphere and reaching the right primary somatosensory cortex showed highly significant differences in all three spatial dimensions in patients with MDD compared to HC. The alterations described herein -along with preliminary evidence from our group and others- suggest diverse symptom-specific and treatment-relevant abnormalities in WM tracts in depression, potentially relevant to neuromodulation approaches to MDD management.

Ventral anterior body of the corpus callosum and right cuneus

Individuals with MDD and High-RNT displayed a larger contribution of WM fibers originated in any of the probed psychosurgical targets in the left hemisphere and traversing an area in the ventral half of the anterior body of the corpus callosum (vabCC, Figure 2), and those reaching the right cuneus. Given the role and anatomical constitution of the CC, those fibers would have, as their contralateral destination, subcortical structures of the right hemisphere (36–39). Specifically, the vabCC contains fibers that are directed to subcortical structures including the thalamus, and that conform in part the anterior limb of the internal capsule (36). This observation agrees with previous evidence supporting excess interhemispheric WM connections in discrete CC regions in some groups of patients with MDD. Thus, patients with MDD and comorbid anxiety disorders display an excess of CC volume in the isthmus (40). Whereas we can only speculate on the similarities between such patients and our own sample, RNT is a transdiagnostic symptom affecting anxiety disorders in the form of worry (4). If the MDD patients with comorbid anxiety in the sample of Walterfang and coworkers (40) displayed a significant degree of rumination and worry, their study would be an important antecedent supported by present findings. Also, volumetric differences in the CC characteristic of depression appear to be largely heritable (41), especially in the region that contains the vabCC. This is compatible with our observation on the relationship between RNT (a trait-like characteristic usually preexisting MDD onset (42)), and excess fibers in the vabCC. Last, a recent study (39) reported functional abnormalities related to RNT in MDD that were explained by structural abnormalities in the CC. Albeit in all cases focused on structural callosal abnormalities, the differences between our study and that of Zhang and coworkers (39) and Walterfang and coworkers (40) could be due in part to the fact that we specifically focused on tracts involved in psychosurgical procedures, thus possibly underestimating RNT-related callosal structural abnormalities in other CC subregions. The cuneus is a cortical area concerned with mental imagery, and as such it displays a physiological relationship with the DMN, active during self-referential processing (43). In fact, graph-based analysis revealed aberrant structural connectivity between DMN nodes in the first such study in MDD (44). Our observation of decreased size of WM tracts reaching the left PCC (a prominent DMN node) supports the findings of that pioneering study. More recent data suggest, in fact, that trait rumination in MDD is largely unrelated to DMN connectivity (45). On the other hand, we recently observed that modulation of this region via real-time neurofeedback results in less ruminative thinking (46), further supporting the potential role of this area in successful RNT-specific neuromodulation in MDD.

Right Medial Orbitofrontal Cortex

The OFC has long been recognized as a structure that is highly relevant to the pathophysiology of MDD (47–49). Chronic stress resulting in depression-like states, is known to induce increased dendritic spine growth and arborization in this cortical region (50,51). Also, disruption of connectivity between OFC and mediodorsal thalamus, by both long-term depression (52) and ketamine administration (53) seems to have significant, reward-related antidepressant effects. Coincidentally, clinical stimulation of the right OFC has been observed to induce global alleviation of depressive symptoms (54). The mechanisms whereby OFC function manipulations affect mood are less well understood. In this regard, the OFC is conceptualized as a major mediator of reward responses in humans and nonhuman primates (48), and its medial portion more specifically is purported to signal reward (49,55). In agreement with this hypothesis and with our present results, different authors have observed distinctly increased cortical thickness in the right mOFC in community-dwelling adults as a function of anhedonia (56), in persons at-risk for MDD (57), and in first-episode, treatment-naïve patients with MDD (58) (but see also (59)). Last, we have recently observed that reward deficits are widespread in patients with MDD regardless of their level of RNT, further suggesting that MDD-related structural WM connectivity characteristics observed herein, represent an abnormality that is not related to RNT (21). Whether the beneficial role of surgical interruption of projections to the right mOFC in MDD is related to the modulation of reward mechanisms, however, remains open to further investigation.

Left primary motor cortex

Functional motor cortex abnormalities in mood disorders including MDD have been extensively documented in the literature (60,61). In MDD, the motor cortex has been proposed to represent a final common pathway for a variety of neurobiological mechanisms explaining abnormalities of psychomotor behavior, prominent in MDD (61), but purportedly present in a continuum between normal motor activity and extreme clinical situations, represented by the transdiagnostic syndrome of catatonia (62). Subcortical systems of motor control including dopaminergic (63,64) and serotonergic (63–65), as well as cortico-cortical regulation (including reciprocal control exerted on the motor system by the salience and executive control networks) (39,66) are thus proposed to converge on the primary motor cortex to produce prominent clinical manifestations of psychomotor retardation across diagnoses (61,67). Our finding of a deficit of WM connections converging onto the left, or dominant, motor cortex as affected by psychosurgical lesions useful in the treatment of MDD support this view, and that direct modulation of the motor cortex has been proposed as a potential therapeutic mechanism in MDD (61).

Other relevant anatomical findings

Whereas not exhibiting directional changes regarding the size of the involved WM tracts, the finding of aberrant anatomical disposition of tracts reaching the right primary somatosensory cortex, deserve consideration in the pathophysiology of MDD. The postcentral gyrus, encompassing areas 3, 2, and 1 of Brodmann, is the primary somatosensory cortex, receiving projections from the thalamus and integrating information from the body. However, the postcentral gyrus is also a site that contributes to sensing internal bodily responses (68) and in the right hemisphere specifically, it has long been noted to be a critical area in the recognition of emotional face expression (69), suggesting that this region is critically involved in emotional regulation (70). Furthermore, changes in structure and function of the postcentral gyri have been documented in MDD and anxiety disorders in several studies (71–73). A recent communication has described the right somatosensory cortex, along with the posterior insula, as a critical hub mediating abnormal reactions to social touch and interpersonal distance in persons subjected to severe childhood adversity (74). These abnormalities are shared by MDD patients, and in fact childhood adversity is a frequent complicating factor in MDD, conditioning in part treatment resistance in this disorder (3).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study, which limits the inferences that can be drawn regarding causal relationships between WM tract characteristics and levels of RNT.

Second, any tractography method could yield results not entirely overlapping with actual anatomical findings, despite major recent advances in translatability (75), with strong evidence for accurate depiction of WM anatomy predicting the actual position of surgical brain targets (e.g. (76)) including tract-specific clinical efficacy in the treatment of depression (54,77).

Third, structural definition of connections does not imply changes in the direction of functional connectivity. For example, in the landmark study of Kargaonkar and coworkers (44), fewer connections between components of the default mode network (DMN) were observed, which was associated with the hypothesis that DMN functional connectivity is increased in this disorder. Also, in a preliminary analysis we compared MDD patients and HC regarding tracts linking the superior temporal sulcus and the anterior insula, which exhibit increased functional connectivity in relation to intensity of RNT (22) and found no structural differences (not shown). Therefore, the finding of structural correlates of MDD and its symptoms can be considered as a first step to direct further inquiry into their role in the production of disease and its treatment.

Fourth, whereas simulated lesion areas as defined in this study approach actual psychosurgical lesions (24), real surgical lesions may engage a larger number, and a more variable distribution of WM connections, than those observed in our simulation. This is especially true for SCT, which was originally defined as a non-spherical radiation lesion extending beyond the caudate head into the gyrus rectus (23).

As stated above, the symptom specificity of these lesions was only tested for RNT, and some of the RNT-unrelated WM tract differences respect of HC may well be related to other symptom dimensions, including anhedonia and psychomotor retardation, as suggested by the involvement of brain regions implicated in those symptoms in previous studies. Unfortunately, the study was not originally designed to probe those behavior dimensions, and we lack specific behavioral measures of reward and psychomotor activity. The relationship between intergroup WM differences and symptom dimensions other than RNT, remains unsettled and open to further investigation, as does any gender specificity of the present findings. Whereas the present study was not designed with this purpose, there is evidence that women tend to ruminate more than men and that this might be one of the factors explaining their higher prevalence of MDD (78). Further, in alignment on prior literature, participants with higher RNT were also more functionally impaired despite similar depression severity, as shown in Table 1 (4–7,9). In fact, while the comparison method chosen (propensity score matching) has certain advantages (including no assumptions of linearity between variables and outcomes, and a quasi-randomized design without model selections that could be biased by the researcher (79)), this method yielded a smaller sample, which in turn could lead to a loss of information compared to a regression model using a bigger sample.

Conclusion

We partially confirmed the initial hypothesis of the present study, namely, that psychosurgical targets useful in the treatment of depression engage brain anatomical circuits associated with intensity of RNT. RNT was specifically associated with excess WM fibers originated in left-hemisphere targets and traversing the vabCC. However, MDD was also associated to excess fibers originated in both hemispheres and converging onto the right mOFC, and smaller left WM tracts reaching ipsilateral primary motor, middle frontal, and posterior cingulate cortices, regardless of RNT. Our observation of MDD association to both increased and decreased size of WM tracts can be best appreciated considering previous results on structural connectivity in MDD (44, 80). The first description of WM connectivity in MDD (44) observed a decrease in the number of streamlines between DMN nodes, and between thalamus and frontal gyri. A recent study comparing HC and psychiatric patients with mood disorders and schizophrenia, did not detect absolute changes in the number of streamlines between HC and MDD (80). Our observation of variable WM tract size depending upon the connection considered, suggests a general assertion on increased or decreased WM connectivity in MDD cannot be made. Nonetheless, as explained above, our observation of smaller WM tracts reaching the PCC in MDD, coincides with the original description of structural DMN connectivity in this disorder (44).

Whereas in this study we focused on MDD, the same psychosurgical targets have been successfully used in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and in fact burgeoning literature on surgical neuromodulation addresses both disorders jointly (81). Further studies would be necessary to establish the specificity of the present structural findings. A recent comprehensive review failed to observe consistent, transdiagnostic correlates of RNT (82). Nevertheless, an emerging concept to be confirmed is the laterality of disease-specific findings, especially right-sided structural findings in both MDD and OCD (83,84).

While in the present study we chose to focus on psychosurgery targets on the hope to detect WM tracts relevant to MDD pathogenesis and treatment, further studies will be necessary to confirm a causal role for our observations, and in this regard, the present study is not necessarily better than a whole-brain, data-driven approach. Moreover, our sample of MDD participants was not entirely composed of individuals who display treatment resistance, and therefore our results might not be immediately generalizable to this group with possible neurobiological peculiarities (9). Nonetheless, by defining specific brain circuit-symptom relationships, our results might be a steppingstone to detect patterns of brain connectivity whose modulation could be used to improve prognosis in MDD (10).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported in part by the William K. Warren Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Center Grant Award Number 1P20GM121312. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The funder had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The ClinicalTrials.gov identifier for the clinical protocol associated with data published in the current paper is NCT02450240, “Latent Structure of Multi-level Assessments and Predictors of Outcomes in Psychiatric Disorders” (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02450240).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Paulus is an advisor to Spring Care, Inc., a behavioral health startup, and he has received royalties for an article about methamphetamine in UpToDate. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. (2006): Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STARD*D report. Am J Psychiatry 163:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaynes BN, Asher G, Gartlehner G, Hoffman V, Green J, Boland E, et al. (2018): Definition of treatment resistant depression in the Medicare population. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 Feb 9. AHRQ Technology Assessments. Bookshelf ID: NBK526366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemeroff CB (2020): The state of our understanding of the pathophysiology and optimal treatment of depression: Glass half full or half empty? Am J Psychiatry 177(8):671–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEvoy PM, Watson H, Watkins ER, Nathan P (2013): The relationship between worry, rumination, and comorbidity: evidence for repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic construct. J Affect Disord 151(1):313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinhoven P, Drost J, van Hemert B, Penninx BW (2015): Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. J Anxiety Dis 33:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law KC, Tucker RP (2018): Repetitive negative thinking and suicide: a burgeoning literature with need for further exploration. Curr Opin Psychol 22:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers ML, Joiner TE (2018): Suicide-specific rumination relates to lifetime suicide attempts above and beyond a variety of other suicide risk factors. J Psychiatr Res 98:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves PN, Foulon C, Karolis V, Bzdok D, Margulies DS, Volle E, et al. (2019): An improved neuroanatomical model of the default-mode network reconciles previous neuroimaging and neuropathological findings. Comm Biol 2:370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Runia N, Yuecel DE, Lok A, de Jong K, Denys DAJP, van Wingen GA, Bergfeld IO (2022): The neurobiology of treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 132:433–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Ball TM, Samara S, Staveland BR, Keller AS, Fleming SL, et al. (2021): Mapping neural circuit biotypes to symptoms and behavioral dimensions of depression and anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 91:561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah P, Glabus M, Goodwing G, Ebmeier K (2002): Chronic, treatment-resistant depression and right fronto-stiatal atrophy. Br J Psychiatry 180:434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Qin LD, Chen J, Qian LJ, Tao J, Fang YR, Xu JR (2011): Brain microstructural abnormalities revealed by diffusion tensor images in patients with treatment-resistant depression compared with major depressive disorder before treatment. Eur J Radiol 80(2):450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma C, Ding J, Li J, Guo W, Long Z, Liu F, et al. (2012): Resting-state functional connectivity bias of middle temporal gyrus and caudate with altered grey matter volume in major depression. PLoS One 7(9):e45263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serra-Blasco M, Portella MJ, Gomez Anson B, de Diego-Adelino J, Vives-Gilaber Y, Puigdemont D, et al. (2013): Effects of illness duration and treatment resistance on grey matter abnormalities in major depression Br J Psychiatry 202:434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Diego-Adelino J, Pires P, Gomez-Anson B, Serra-Blasco M, Vives-Gilabert Y, Puigdemont D, et al. (2014): Microstructural white matter abnormalities associated with treatment resistance, severity and duration of illness in major depression. Psychol Med 44(6):1171–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riva-Posse P, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, McIntyre CC, Gross RE, Chaturvedi A, et al. (2014): Defining critical white matter pathways mediating successful subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 76(12):963–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riva-Posse P, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, Crowell AL, Garlow SJ, Rajendra JK, et al. (2018): A connectomic approach for subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation surgery: prospective targeting in treatment-resistant depression. Mol Psychiatry 23:843–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth SA, Bijanki KR, Metzger B, Allawala A, Pirtle V, Adkinson JA, et al. (2022): Deep brain stimulation for depression informed by intracranial recordings. Biol Psychiatry 92(3):246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983): The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum PR (2015): Observational studies: Overview. In Wright JD (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Oxford: Elsevier Ltd. pp. 107–112 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H, Kirlic N, Kuplicki R, Tulsa 1000 Investigators, Paulus M, Guinjoan SM (2022): Neural processing dysfunctions during fear learning but not reward-related processing characterize depressed individuals with high levels of repetitive negative thinking. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimag 7(7):716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuchiyagaito A, Sanchez SS, Misaki M, Kuplicki R, Park H, Paulus MP, Guinjoan SM (2022): Intensity of repetitive negative thinking in depression is associated to greater functional connectivity between semantic processing and emotion regulation areas. Psychol Med, in press. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722002677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bridges PK, Bartlett JR, Hale AS, Poynton AM, Malizia AL, Hodgkiss AD (1994): Psychosurgery: stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. An indispensable treatment. Br J Psychiatry 165:599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoene-Bake JC, Parpaley Y, Weber B, Panksepp J, Hurwitz TA, Coenen VA (2010): Tractographic analysis of historical lesion surgery for depression. Neuropsychopharmacol 35:2553–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolomeo S, Christmas D, Jentzsch I, Johnston B, Sprengelmeyer R, Matthews K, Steele JD (2016): A causal role for the anterior mid-cingulate cortex in negative affect and cognitive control. Brain 139:1844–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avecillas-Chasin JM, Hurwitz TA, Bogod NM, Honey CR (2019): An analysis of clinical outcome and tractography following bilateral anterior capsulotomy for depression. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 97:369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez SM, Duarte-Abritta B, Abulafia C, De Pino G, Bocaccio H, Castro MN, et al. (2020): White matter fiber density abnormalities in cognitively normal adults at risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatr Res 122:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuplicki R, Touthang J, Al Zoubi O, Mayeli A, Misaki M, NeuroMAP Investigators, et al. (2021): Common data elements, scalable data management infrastructure, and analytics workflows for large-scale neuroimaging studies. Front Psychiatry 12:682495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. (1998): The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59 (Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tournier JD, Calamante F, Connelly A (2007): Robust determination of the fibre orientation distribution in diffusion MRI: non-negativity constrained super-resolved spherical deconvolution. Neuroimage 35(4):1459–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeurissen B, Leemans A, Jones DK, Tournier JD, Sijbers J (2011): Probabilistic fiber tracking using the residual bootstrap with constrained spherical deconvolution. Hum Brain Mapp 32:461–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith RE Tournier JD Calamante F Connelly A (2013): SIFT: spherical-deconvolution informed filtering of tractograms. Neuroimage 67:298–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. (2006): An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31(3):968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald JH (2014): Handbook of Biological Statistics (3rd ed.). Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore. pp. 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995): Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B (Methodological) 57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang H, Zhang J, Jiang H, Wakana S, Poetscher L, Miller MI, et al. (2005): DTI tractography based parcellation of white matter: application to the mid-saggital morphology of corpus callosum. NeuroImage 26:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofer S, Frahm J (2006): Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited - comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage 32:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedrich P, Forkel SJ, Thiebaut de Schotten M (2020): Mapping the principal gradient onto the corpus callosum. NeuroImage 223:117317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang R, Tam SKTS, Wong NML, Wu J, Tao J, Chen L, et al. (2022): Aberrant functional metastability and structural connectivity are associated with rumination in individuals with major depressive disorder. NeuroImage Clin 33:102916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walterfang M, Yuecel M, Barton S, Reutens DC, Wood AG, Chen J, et al. (2009): Corpus callosum size and shape in individuals with current and past depression. J Affect Dis 115:411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woldehawariat G, Martinez PE, Hauser P, Hoover DM, Drevets WWC, McMahon FJ (2014): Corpus callosum size is highly heritable in humans, and may reflect distinct genetic influences on ventral and rostral regions. PLOS One 9(6):e99980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw ZA, Hild LM, Starr LR (2019): The developmental origins of ruminative response style: an integrative view. Clin Psychol Rev 74:101780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J (2019): The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nat Rev Neurosci 20(10): 624–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korgaonkar MS, Fornito A, Williams LM, Grieve SM (2014): Abnormal structural networks characterize major depressive disorder: a connectome analysis. Biol Psychiatry 76: 567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tozzi L, Zhang X, Chesnut M, Holt-Gosselin B, Ramirez CA, Williams LM (2021): Reduced functional connectivity of default mode network subsystems in depression: meta-analytic evidence and relationship with trait rumination. Neuroimage Clin 30: 102570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuchiyagaito A, Misaki M, Kirlic N, Yu X, Sanchez SM, Cochran G, et al. (2022): Real-time fMRI functional connectivity neurofeedback reducing repetitive negative thinking in depression: a double-blind randomized sham controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kringelbach M (2005): The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:691–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rolls ET (2019): The orbitofrontal cortex and emotion in health and disease, including depression. Neuropsychologia 128:14–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pizzagalli DA, Roberts AC (2021): Prefrontal cortex and depression. Neuropsychopharmacol 47:225–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyman SE (2012): Revolution stalled. Sci Transl Med 4(155):155cm11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pizzagalli DA (2014): Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10:393–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kangas BD, Wooldridge LM, Luc OT, Bergman J, Pizzagalli DA (2020): Empirical validation of a touchscreen probabilistic reward task in rats. Transl Psychiatry 10(1):285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Der-Avakian A, D’Souza MSS, Pizzagalli DAA, Markou A (2013): Assessment of reward responsiveness in the response bias probabilistic reward task in rats: implications for cross-species translational research. Transl Psychiatry 3(8):e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scangos KW, Makhoul GS, Sugrue LP, Chang EF, Krystal AD (2021): State-dependent responses to intracranial brain stimulation in a patient with depression. Nat Med 27(2):229–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rolls ET, Cheng W, Feng J (2020): The orbitofrontal cortex: reward, emotion and depression. Brain Comm 2(2):fcaa196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dotson VM, Taiwo Z, Minto LR, Bogoian HR, Gradone AM (2021): Orbitofrontal and cingulate thickness asymmetry associated with depressive symptom dimensions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 21:1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peterson BS, Warner V, Bansal R, Zhu H, Hao X, Liu J, et al. (2009): Cortical thinning in persons at increased familial risk for major depression. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 106(15):6273–6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qiu L, Lui S, Kuang W, Huang X, Li J, Li J., et al. (2014): Regional increases of cortical thickness in untreated, first-episode major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry 4:e378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang XH, Wang Y, Huang J, Zhu CY, Liu XQ, Cheung EF, et al. (2015): Increased prefrontal and parietal cortical thickness does not correlate with anhedonia in patients with untreated first-episode major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res 234(1):144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernard JA, Mittal VA (2015): Updating the research domain criteria: the utility of a motor dimension. Psychol Med 45:2685–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Northoff G, Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Magioncalda P, Martino M (2021): All roads lead to the motor cortex: psychomotor mechanisms and their biochemical modulation in psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry 26:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirjak D, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Fritze S, Sambataro F, Kubera KM, Wolf RC (2018): Motor dysfunction as research domain across bipolar, obsessive-compulsive and neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 95:315–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anand A, Jones SE, Lowe M, Karne H, Koirala P (2018): Resting state functional connectivity of dorsal raphe nucleus and ventral tegmental area in medication-free young adults with major depression. Front Psychiatry 9:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wohlschlager A, Karne H, Jordan D, Lowe MJ, Jones SE, Anand A (2018): Spectral dynamics of resting state fMRI within the ventral tegmental area and dorsal raphe nuclei in medication-free major depressive disorder in young adults. Front Psychiatry 9:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han S, He Z, Duan X, Tang Q, Chen Y, Yang Y, et al. (2019): Dysfunctional connectivity between raphe nucleus and subcortical regions presented opposite differences in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 92:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martino M, Magioncalda P, Yu H, Li X, Wang Q, Meng Y, et al. (2018): Abnormal resting-state connectivity in a substantia nigra-related striato-thalamo-cortical network in a large sample of first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 44:419–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Northoff G, Wiebking C, Feinberg T, Panksepp J (2011): The ‘resting state hypothesis’ of major depressive disorder-a translational subcortical-cortical framework for a system disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:1929–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ (2004): Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci 7:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adolphs R, Damasio H, Tranel D, Cooper G, Damasio AR (2000): A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of emotion as revealed by three-dimensional lesion mapping. J Neurosci 20:2683–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Satpute AB, Kang J, Bickart KC, Yardley H, Wager TD, Barrett LF (2015): Involvement of sensory regions in affective experience: A meta-analysis. Front Psychol 6:1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi H, Ning Y, Li J, Guo S, Chi M, Gao M, et al. (2014): Gray matter volume abnormalities in depressive patients with and without anxiety disorders. Medicine (Baltimore) 93(29):e345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tadayonnejad R, Yang S, Kumar A, Ajilore O (2015): Clinical, cognitive, and functional connectivity correlations of resting-state intrinsic brain activity alterations in unmedicated depression. J Affect Disord 172: 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmaal L, Hibar DP, Sämann PG, Hall GB, Baune BT, Jahanshad N, et al. (2016): Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry 22(6):900–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maier A, Gieling C, Heinen-Ludwig L, Stefan V, Schultz J, Gunturkun O, et al. (2020): Association of childhood maltreatment with interpersonal distance and social touch preferences in adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 177:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wende T, Hoffmann KT, Meixensberger J (2020): Tractography in neurosurgery: a systematic review of current applications. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 81(5):442–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jacquesson T, Cotton F, Attye A, Zaouche S, Tringali S, Bosc J, et al. (2019): Probabilistic tractography to predict the position of cranial nerves displaced by skull base tumors: value for surgical strategy through a case series of 62 patients. Neurosurgery 85(10):E125–E136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Riva-Posse P, Inman CS, Choi KS, Crowell AL, Gross RE, Hamann S, Mayberg HS (2019): Autonomic arousal elicited by subcallosal cingulate stimulation is explained by white matter connectivity. Brain Stimul 12(3):743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson DP, Whisman MA (2013): Gender differences in rumination: a meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif 55(4): 367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benedetto U, Head SJ, Angelini GD, Blackstone EH (2018): Statistical primer: propensity score matching and its alternatives. Eur J Cardiothor Surg 53(6): 1112–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Repple J, Gruber M, Mauritz M, de Lange SC, Winter NR, Opel N, et al. (2023): Shared and specific patterns of structural brain connectivity across affective and psychotic disorders. Biol Psychiatry 93: 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davidson B, Eapen-John D, Mithani K, Rabin JS, Meng Y, Cao X, et al. (2022): Lesional psychiatric neurosurgery: meta-analysis of clinical outcomes using a transdiagnostic approach. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 93: 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Demnitz-King H, Goehre I, Marchant NL (2021): The neuroanatomical correlates of repetitive negative thinking: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 316: 111353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lippitz BE, Mindus P, Meyerson B, Kihlstrom L, Lindquist C (1999): Lesion topography and outcome after thermocapsulotomy or gamma knife capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: relevance of the right hemisphere. Neurosurgery 44(3): 452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baldermann JC, Melzer C, Zapf A, Kohl S, Timmermann L, Tittgemeyer M, et al. (2019): Connectivity profile of effective deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 85: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.