Abstract

Background

Donor human milk banks use Holder pasteurization (HoP; 62.5°C, 30 min) to reduce pathogens in donor human milk, but this process damages some bioactive milk proteins.

Objectives

We aimed to determine minimal parameters for high-pressure processing (HPP) to achieve >5-log reductions of relevant bacteria in human milk and how these parameters affect an array of bioactive proteins.

Methods

Pooled raw human milk inoculated with relevant pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Cronobacter sakazakii) or microbial quality indicators (Bacillus subtilis and Paenibacillus spp. spores) at 7 log CFU/mL was processed at 300–500 MPa at 16–19°C (due to adiabatic heating) for 1–9 min. Surviving microbes were enumerated using standard plate counting methods. For raw milk, and HPP-treated and HoP-treated milk, the immunoreactivity of an array of bioactive proteins was assessed via ELISA and the activity of bile salt-stimulated lipase (BSSL) was determined via a colorimetric substrate assay.

Results

Treatment at 500 MPa for 9 min resulted in >5-log reductions of all vegetative bacteria, but <1-log reduction in B. subtilis and Paenibacillus spores. HoP decreased immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin M (IgM), immunoglobulin G, lactoferrin, elastase and polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) concentrations, and BSSL activity. The treatment at 500 MPa for 9 min preserved more IgA, IgM, elastase, lactoferrin, PIGR, and BSSL than HoP. HoP and HPP treatments up to 500 MPa for 9 min caused no losses in osteopontin, lysozyme, α-lactalbumin and vascular endothelial growth factor.

Conclusion

Compared with HoP, HPP at 500 MPa for 9 min provides >5-log reduction of tested vegetative neonatal pathogens with improved retention of IgA, IgM, lactoferrin, elastase, PIGR, and BSSL in human milk.

Keywords: breast milk, mother’s milk, thermal processing, infant nutrition, preterm infant, premature infant, antibody, microbial inactivation, protease, enzyme

Introduction

Premature infant’s lack of physiological development at birth leaves them at increased risk for poorer growth, suboptimal neurological developmental outcomes and infection given their lack of physiological development at birth. Compared with formula, feeding preterm infants human milk reduces risk of necrotizing enterocolitis [1], sepsis [2], abnormal brain development [3] and features predictive of high blood pressure [4]. Part of human milk functionality is derived from its complex array of hundreds of proteins, which have been identified in proteomic studies [[5], [6], [7]]. Many of these identified proteins have known functions, at least in vitro and, in some cases, animal and human studies. For example, lactoferrin [8] and α-lactalbumin [[9], [10]] can enhance mineral absorption. Likewise, bile salt-stimulated lipase (BSSL) [11], milk proteases and antiproteases [12] are involved in fat and protein digestion, respectively. Lactoferrin [[13], [14], [15]], lysozyme [16], Ig [17], and haptocorrin [18] defend against bacterial and viral pathogens. Cytokines [19] and osteopontin [20] modulate the immune system. Epidermal growth factor [21], transforming growth factor β1, transforming growth factor β2 [22], and lactoferrin [23] can influence the development of the gastrointestinal system. A small number of these proteins (for example, lactoferrin, secretory IgA and lysozyme) have been shown to survive digestion in infants to at least a small degree [24,25], which may allow them to exert activity within the infant.

Though parent own milk is preferred for preterm infants, the majority of lactating parents of very low birth weight infants are unable to provide an adequate supply of milk, making supplementation with donor human milk necessary [26,27]. Given this limitation, preterm infants are often fed donor human milk during their hospitalization [28]. Pathogens can be present in raw human milk, either from the parent (from the mammary gland or skin) or from environmental contamination (from pumps, bottles, etc.) that could harm a preterm infant. Pathogens that can be present in human milk include Salmonella, Group B Streptococcus, Staphylococcus [29,30] (and specifically S. aureus [31], Listeria monocytogenes [32], Cronobacter sakazakii [33], and Enterococcus faecium [34]. Aerobic endospore-forming bacteria of the genera Bacillus and Paenibacillus are also common members of the human milk microbiome [35]. To reduce risk of the transmission of pathogens to infants via donor human milk, nonprofit milk banks apply Holder pasteurization (HoP) (62.5 ºC, 30 min), which causes a >5-log reduction of many of the key human milk bacterial and viral pathogens [36]; however, this treatment is ineffective against bacterial spores (i.e., Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp.) [[37], [38], [39]]. HoP completely or partially inactivates an array of bioactive milk proteins, including enzymes (for example, BSSL) [40], lactoferrin [41,42]), immune proteins (for example, IgA [43] and IgG [44] and others [45]).

The degradation of bioactive proteins by HoP could preclude preterm infants from gaining the health advantages of those proteins’ bioactivities in donor human milk. For example, human milk BSSL assists in fat digestion in the infant and the loss of BSSL in HoP-treated milk may be partially responsible for the observed lower fat absorption, weight gain, and length gain in infants fed HoP-treated milk in comparison with those fed unheated human milk [[46], [47], [48], [49]]. Clearly, investigation of alternative nonthermal processing methods to better preserve milk bioactive proteins is warranted.

High-pressure processing (HPP) is a nonthermal technology currently used in the food industry to inactivate microorganisms. HPP uses water as a medium to transmit pressure (100–800 MPa) without applying heat [50]. The applied pressure inactivates microorganisms by creating temporary porosity of cell membranes, which causes leakages of intracellular molecules and disrupts ion/pH gradients, and by denaturing some microbial proteins, particularly enzymes, which can alter biochemical reactions in the cell and disrupt genetic mechanisms [51,52].

Applying 400–800 MPa for a brief period of time (<5–10 min) to human milk reduces selected pathogenic microorganisms by a >5-log [50]. HPP at 500 MPa for 8 min reduced the viable bacteria in donor human milk from samples originally containing >7.7 log CFU/L to <3 log CFU/L (i.e., <1 CFU/mL, the microbial safety threshold commonly used by milk banks) in 71% of samples tested (a percentage efficacy that was not significantly different from that for HoP) [53]. Moreover, 500 MPa for 8 min caused less degradation of BSSL and lactoferrin in those donor human milk samples than those after HoP treatment [53]. Likewise, in our own recent study, HPP treatment at 550 MPa for 5 min resulted in less decrease in BSSL activity than HoP treatment [40]. However, systematically identifying the minimum processing conditions required for HPP to achieve a >5-log reduction in spiked pathogenic bacteria has not been carried out, including which conditions better preserve a larger array of milk proteins. Before the implementation of a new technology like HPP in donor human milk processing, it is critical to obtain data on preservation of milk protein components and microbial inactivation. These data will be helpful to make improvements to donor human milk processing and supply infants with milk that better matches parent’s own milk. The aim of this study was to determine the minimal HPP parameters that allow a >5-log reduction of key pathogens while preserving bioactive proteins in donor human milk. Our hypotheses are that: 1) specific HPP treatment parameters will allow >5-log reduction of key pathogens; 2) specific HPP treatments will not cause a significant decrease in bioactive protein retention compared with raw milk; and 3) specific HPP treatments will allow a higher bioactive protein retention compared with HoP.

Methods

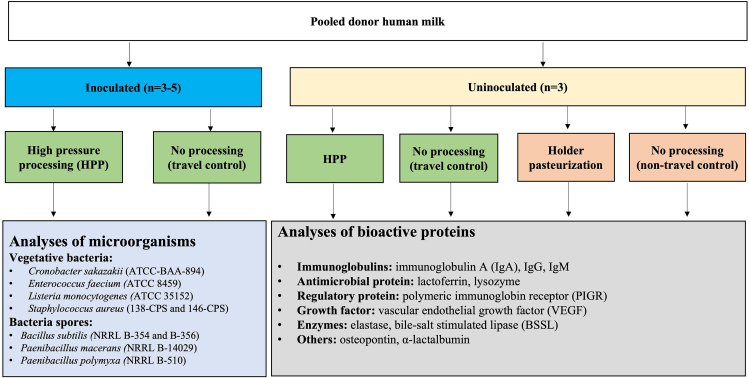

The overall study design is summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overall experimental design. A large volume (>50 L) of donor human milk was collected from a large number of donors and separated into two arms of the study. One division was inoculated with bacterial species of interest and the other remained uninoculated. Milk was aliquoted into plastic pouches and inoculated on three separate occasions with various pathogenic bacteria at a concentration of 7 log CFU/mL. Uninoculated milk was similarly aliquoted into pouches. Samples were shipped on dry ice to the HPP processing facility and returned after HPP treatments (HPP: 300–500 MPa, 1–9 min; n = 3–5 processing trials per treatment). Concurrently, the same pool of milk was treated by HoP (n = 3) in our laboratory. Samples from the inoculated arm of the study were enumerated for surviving bacteria, whereas the concentrations of bioactive proteins were measured in samples from the uninoculated arm. HoP, Holder pasteurization; HPP, high-pressure processing.

Donor human milk

A large volume (>50 L) of frozen, untreated, human milk was collected and provided by Northwest Mothers Milk Bank (Portland, OR). The informed consent procedure was managed by the Northwest Mothers Milk Bank. The donated human milk samples were stored at –20 °C. Individual bags of frozen donor human milk were placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 48 h to thaw. After thawing, individual bags were pooled and frozen immediately at –20 °C for storage until needed for experimentation. The same pooled human milk was used throughout the entire study to minimize potential confounding factors associated with differences in milk composition. In total, the pooled milk samples went through two freeze–thaw cycles before being analyzed.

Preparation of bacterial cultures and spore suspensions for human milk inoculation

Vegetative bacterial strains and spore-forming bacteria were selected for inoculation in this study based on their potential presence in donor human milk and/or the detection of their species or genera in donor human milk as contaminants (Supplemental Table 1) [54]. All bacteria were maintained cryogenically by the Food Safety Systems Lab (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR). Individual bacterial strains were revived from frozen stock culture (−80 °C) by inoculating into Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; Neogen, Lansing, MI) except for L. monocytogenes, which was cultured in TSB supplemented with 0.6% yeast extract (Neogen). Paenibacillus spp. were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, whereas all other cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The morphology of each vegetative bacteria was verified using selective agar specified in Table 1. A single representative colony was transferred from the selective media of each bacterium to 10 mL of TSB and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h until a concentration of 8 log CFU/mL was achieved. Spore suspensions were prepared separately for the B. subtilis strains and Paenibacillus species. Spore-forming bacterial strains were individually sporulated by surface plating on specific sporulation agar and incubated according to Supplemental Table 1. Sporulation was confirmed by light microscopy using spore staining [55].

TABLE 1.

Recovery rate of spiked proteins in human milk

| Targeted protein | ELISA Kit manufacturer (catalog number) | Type of the capture antibody | Type of the detection antibody | Dilution of the milk sample | Spiked protein concentration | Average of the detected total target protein concentration | Target protein concentration in nonspiked samples | Detection efficacy (%) (average ± SD)1 | Detection limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgA | Invitrogen (BMS2096) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 4000 | 50 ng/mL | 96.5 ng/mL | 59.4 ng/mL | 74.2 ± 1.7 | 1.562 ng/mL |

| IgG | Invitrogen (BMS2091) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 200 | 50 ng/mL | 67.7 ng/mL | 36.6 ng/mL | 62.1 ± 1.8 | 1.562 ng/mL |

| IgM | Invitrogen (BMS2098) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 100 | 500 ng/mL | 491.2 ng/mL | 103.4 ng/mL | 77.6 ± 0.7 | 15.62 ng/mL |

| Lactoferrin | Invitrogen (EH309RB) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 10,000 | 91 ng/mL | 200.6 ng/mL | 116.7 ng/mL | 116.7 ± 0.7 | 1.966 ng/mL |

| Lysozyme | Mybiosource (MBS164375) | Monoclonal | Polyclonal | 500 | 40 ng/mL | 73.4 ng/mL | 28.7 ng/mL | 111.7 ± 19.6 | 1.250 ng/mL |

| α-lactalbumin | Mybiosource (MBS2702818) | Polyclonal | Polyclonal | 5000 | 25 ng/mL | 26.5 ng/mL | 3.2 ng/mL | 93.2 ± 18.8 | 0.781 ng/mL |

| PIGR | Mybiosource (MBS2022400) | Polyclonal | Polyclonal | 10 | 400 pg/mL | 647.0 pg/mL | 316.2 pg/mL | 82.7 ± 2.4 | 12.5 pg/mL |

| Osteopontin | Invitrogen (BMS2066) | Polyclonal | Polyclonal | 2500 | 15 ng/mL | 15.5 ng/mL | 8.6 ng/mL | 91.9 ± 2.3 | 0.468 ng/mL |

| VEGF | Invitrogen (KHG0111) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 50 | 375 pg/mL | 353.2 pg/mL | 45.2 pg/mL | 82.2 ± 1.5 | 23.4 pg/mL |

| Elastase | Invitrogen (BMS269) | Monoclonal | Monoclonal | 50 | 2.5 ng/mL | 3.6 ng/mL | 0.9 ng/mL | 101.9 ± 6.8 | 0.156 ng/mL |

PIGR, polymeric immunoglobulin receptor; VEGF, vascular/endothelial growth factor.

The detection efficiency (%) was calculated as (average of detected bioactive protein concentration in the diluted raw milk samples spiked with the bioactive protein—average of detected bioactive protein concentration in the diluted raw milk samples without spiking)/spiked bioactive protein concentration × 100.

Human milk inoculation

The bacterial suspensions grown to 8 log CFU/mL were centrifuged at 6000 × g, and the pellets were resuspended into 10 mL of thawed pooled human milk. The total bacterial count was determined in the milk by serial dilution. An aliquot of the spiked human milk was added to a final volume of 10 mL of additional pooled human milk to achieve a final concentration of 7 log CFU/mL. A cocktail of the 2 strains of S. aureus were prepared by mixing equal volumes of the 2 strains after resuspension in human milk. Two spore cocktails [B. subtilis (2 strains) and Paenibacillus spp. (2 strains)] were prepared. An aliquot (10 mL) of each of the previously prepared spore preparations was centrifuged at 6000 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of human milk. Five mL of each relevant resuspended spore preparation were mixed to prepare the spore cocktails. These spore suspension cocktails were inoculated into human milk to obtain a final spore density of 6 log CFU/mL.

Human milk HPP

Inoculated and noninoculated pooled human samples were aliquoted (2 mL) into high-barrier bags (Vacuum Sealers Unlimited, CA), vacuum-sealed, and shipped overnight on dry ice for HPP treatment. Inoculated travel-control samples were shipped with those processed by HPP but not treated. Uninoculated milk samples were also packaged for HPP processing and shipped with inoculated samples (Figure 1). The inoculation of human milk and HPP treatment was repeated three times for all bacteria except for S. aureus for which the treatment was repeated on five separate occasions. Additional processing replicates were required for S. aureus to achieve a >95% statistical confidence of a >5-log reduction. HPP treatment was conducted using a production-scale HPP instrument using water as the pressure transmission medium (2–6 °C) (Avure AV-10, Avure Technologies, Middletown, OH, USA) at the Avure Food Lab (Erlanger, KY). Inoculated pooled milk samples and travel controls were thawed under cold running water for 30 min and processed sequentially thereafter. All samples were kept at 4 °C before and after processing. The inoculated and uninoculated samples were processed at the following pressure–time combinations: 300, 350, 400, 450, and 500 MPa for 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 min. The vessel temperature during HPP ranged from 16 to 19 °C due to adiabatic heating (proportional to pressure) [50]. Pressurization time ranged from 49 to 78 s and depressurization ranged from 11 to 15 s, with times positively correlating with target pressure. Following HPP treatment, samples were frozen and immediately packed in dry ice and shipped to the Food Safety Systems Laboratory via next day air. Upon delivery, the samples were kept frozen at –20 °C and analyzed for bacterial and spore counts within 16 h of arrival. Uninoculated samples for bioactive protein analysis were kept frozen at −80 °C for later analysis.

Human milk HoP

For HoP, 50 mL of thawed, uninoculated human milk was placed in a water bath set to 62.5 °C. The temperature of the human milk was monitored, and when the temperature of the milk samples reached 62.5 °C, the samples were held in the water bath for 30 min to mimic HoP treatment at nonprofit donor milk banks. After HoP, the samples were immediately transferred to an ice bath to support rapid cooling. Heat-treated samples were frozen at −80 °C for later analysis of bioactive proteins. The entire HoP method was repeated on three separate days with aliquots from the same pooled human milk.

Quantification of surviving bacteria

HPP-treated and travel-control samples were thawed at room temperature for 30 min. Microorganisms were enumerated using standard tenfold serial dilution with spread-plating (with 100 μL per plate) trypticase soy agar with 0.6% yeast extract following incubation at 30 °C (Paenibacillus spp.) or 37 °C (all other bacteria) for 48 h. The quantification of surviving bacteria was determined in untreated and HPP-treated milk, but not in HoP-treated human milk because HoP is the current standard of practice for the treatment of human milk, and it is well known to allow >5-log reduction in vegetative bacteria.

Detection and quantification of bioactive proteins by ELISA

Bioactive protein concentrations were determined in untreated, HPP-treated, and HoP-treated human milk samples. Concentrations of IgA, IgG, IgM, lactoferrin, lysozyme, α-lactalbumin, polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR), osteopontin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and elastase in each human milk sample were determined using the ELISA kits listed in Table 1 following the manufacturer’s protocol. As specified in the protocols, centrifugal delipidation was carried out for α-lactalbumin (10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C), elastase (1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), VEGF (1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), PIGR (1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), lactoferrin (1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), lysozyme (5000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C), but not for osteopontin, IgA, IgG, and IgM. Centrifugation steps were carried out after making appropriate dilutions (described in Table 1) to minimize bioactive protein loss. For kits that did not provide specific instructions for handling human milk (osteopontin, IgA, IgG, and IgM), sample preparation with and without centrifugal delipidation after making their corresponding dilutions was carried out in preliminary tests (data not shown). As it did not impact detection at the optimized dilutions, centrifugation was not used in further experiments. Standard curves were created for each analyte. Preliminary tests were performed to determine the optimal dilution values for detection and quantification of each protein (Table 1). Each ELISA kit was validated for use in human milk via spiking experiments to determine the detection efficiency of each protein in human milk at specific dilution levels (Table 1). The targeted bioactive protein standard was spiked into diluted untreated human milk to reach a specific final concentration. The detection efficiency (%) was calculated as (average of detected bioactive protein concentration in the diluted raw milk sample spiked with the bioactive protein – average of detected bioactive protein concentration in the diluted raw milk sample without spiking)/spiked bioactive protein concentration × 100. All measured bioactive protein concentrations were normalized using the detection efficiency of the ELISA (value / detection efficiency %) and expressed as the retention percentage compared with raw milk.

Detection and quantification of BSSL activity

To determine BSSL activity, the concentration of p-nitrophenol cleaved from p-nitrophenyl myristate by BSSL was measured spectrophotometrically using a published method [40] with modifications. Specifically, the dilution of the initial milk samples into distilled water was 1:200. Production of p-nitrophenol was measured by a spectrophotometer (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland) monitoring absorbance at 405 nm at 0 and 15 min with incubation at a constant temperature of 37 °C. The R2 values for the standard curves were in the range 0.991–0.994. The 15-min timepoint was selected because the curve of detected p-nitrophenol over time was linear across this period. The BSSL activity was calculated using the difference of the concentration of the p-nitrophenol (in mM) at 15 min and 0 min divided by the reaction time (15 min) and is expressed as mM p-nitrophenol/min.

Data analysis

Counts of surviving bacterial populations were converted to log CFU/mL prior to statistical analyses. Counts below the limit of detection were assigned a value of 0.5 CFU/mL for statistical purposes. Reductions for each microorganism after HPP treatment were calculated in comparison with the travel-control samples. The 95% CIS were calculated for each processing pressure–time combination for each bacterium. Pressure–time combinations for which the 95% CI was completely above the 5-log CFU/mL reduction threshold were identified. For specific bacteria, if >5-log reductions were not achieved at any pressure–time combination, one-sided t-tests were performed to determine whether any significant log CFU/mL reduction was observed in comparison with the travel control (significance at P < 0.05). A mixed model ANOVA was performed using JMP Pro version 16 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to compare the efficacy of HPP treatment parameters (fixed effects: time, pressure, time∗pressure, trial) for each microorganism. The Tukey Honest Significant Difference procedure was used to determine the differences between mean reduction values of each microorganism, and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

One-sided t-tests were performed (GraphPad Prism software, version 8.2) to determine: 1) whether bioactive protein retention was significantly lower after HoP compared with raw milk; 2) whether bioactive protein retention was significantly lower after specific HPP treatments compared with raw milk; and 3) whether bioactive protein retention was significantly higher after specific HPP treatments compared with HoP. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

HPP efficacy to inactivate vegetative bacteria and spore-forming bacteria in human milk

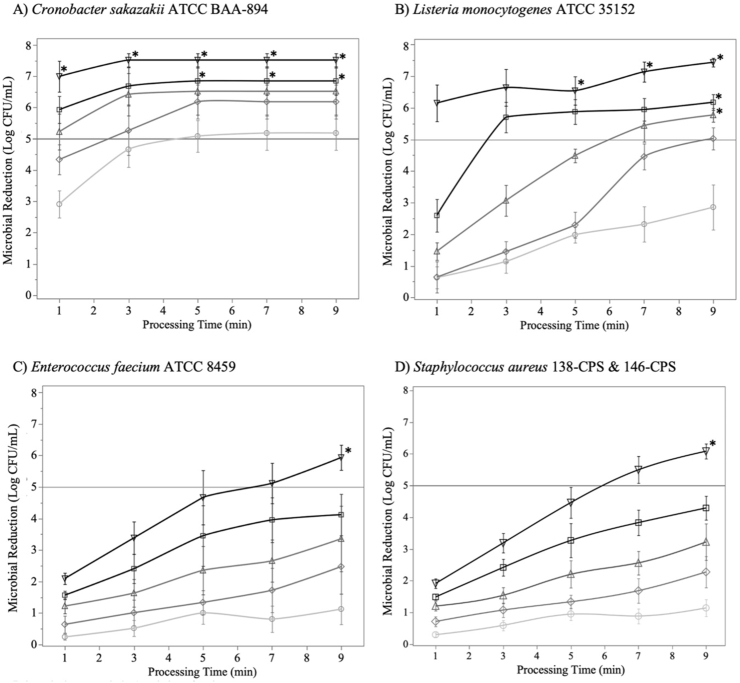

The efficacy of HPP on the inactivation of vegetative bacteria (C. sakazakii, L. monocytogenes, E. faecium and S. aureus) at different doses were determined (Figure 2). Log CFU/mL in the raw milk travel-control samples were 7.52 ± 0.37 for C. sakazakii, 7.45 ± 0.24 for L. monocytogenes, 7.37 ± 0.09 for E. faecium, and 7.63 ± 0.22 for S. aureus. Bacterial strains significantly differed in their sensitivity to HPP processing. C. sakazakii showed high sensitivity to HPP treatment in human milk with 8 of the HPP treatment combinations (450 MPa at 5 min and longer; all 500 MPa treatments) achieving a >5-log reduction with 95% statistical confidence (Figure 2A). Treatments at 500 MPa for 3 min or longer resulted in >7-log reduction of C. sakazakii from the human milk. L. monocytogenes was more resistant to HPP compared with C. sakazakii, particularly at lower pressure (300–400 MPa)—holding time (5 min and less) combinations (Figure 2). The targeted 5-log reduction of L. monocytogenes was consistently achieved for pressure treatments of 400 and 450 MPa at 9 min as well as at 500 MPa with holding time of 5 min or greater (Figure 2B). The gram-positive cocci E. faecium and S. aureus were more resistant to HPP than C. sakazakii and L. monocytogenes (based on the higher pressure and time combinations required for a >5-log reduction of E. faecium and S. aureus, Figure 2). The extent of inactivation of S. aureus and E. faecium increased with increasing pressures and holding times (Figure 2C and D). The targeted 5-log reductions of the S. aureus cocktail and E. faecium were only achieved with statistical confidence at the most extreme HPP treatment (500 MPa, 9 min).

FIGURE 2.

Microbial inactivation (log CFU/mL) of vegetative bacteria in human milk treated with high-pressure processing [HPP: 300–500 MPa (circle represents 300 MPa, diamond represents 350 MPA, triangle represents 400 MPa, square represents 450 MPa, and inverted triangle represents 500 MPa), 1–9 min]. The concentrations of each bacterium were measured in both raw and processed samples. (A) Cronobacter sakazakii ATCC BAA-894. (B) Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 35152, (C) Enterococcus faecium ATCC 8459, and (D) Staphylococcus aureus cocktail (138-CPS and 146-CPS). Data represented as the mean ± standard error (n = 3–4 independent replicates). ∗ indicates that the 95% CI was above the 5-log reduction target.

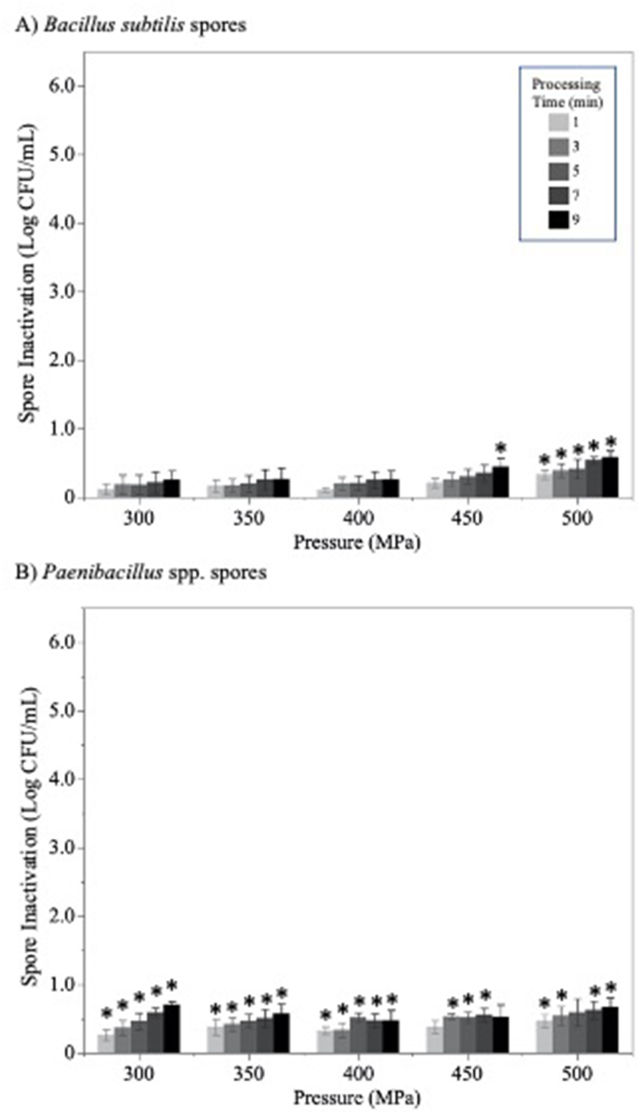

Log CFU/mL in the raw milk travel-control samples were 6.62 ± 0.11 for B. subtilis and 6.35±0.22 for Paenibacillus spp. Bacterial spores were resistant to HPP processing (Figure 3), with none of the pressure–time combinations achieving >1-log reduction. The B. subtilis spore cocktail was more pressure-resistant than the Paenibacillus spp. spore cocktail: minimal, but statistically significant, reductions were achieved for Paenibacillus spores in nearly all pressure treatments (Figure 3B), whereas B. subtilis spores showed significant inactivation following only the most extreme HPP treatments (450 MPa, 9 min and all 500 MPa treatments).

FIGURE 3.

Bacterial spore inactivation (log CFU/mL) in human milk treated with high-pressure processing (HPP: 300–500 MPa, 1–9 min). (A) Bacillus subtilis spore cocktail (NRRL B-354 and NRRLB-356) and (B) Paenibacillus spp. spore cocktail (P. macerans NRRL B-14029 and P. polymyxa NRRL B-510). Data represented as the mean ± standard error (n = 3 independent replicates). ∗ indicates significantly (P < 0.05) different from the travel control based on one-sided t-tests.

Effect of HPP and HoP on bioactive human milk proteins measured by ELISA or activity assay

Dilution factors were independently optimized for the quantification of each target protein and ranged between 10-1 and 10-4 (Table 1). The detection limit for each targeted protein is listed in Table 1. The detection efficiency (%) ranged from 62% to 116%. The data of the bioactive proteins in raw milk, and HPP-, and HoP-treated human milk are presented in Supplemental Table 2. In the current study, the bioactive protein concentration in both travel control (raw milk sample shipped to the HPP facility on dry ice without HPP treatment) and nontravel control (raw milk sample kept in the lab freezer) were analyzed, and the data are presented in Supplemental Table 3. No significant difference was observed in the bioactive protein concentration between travel-control samples and nontravel control samples. For the following comparison, only nontravel control samples, which are referred to as Raw, were used.

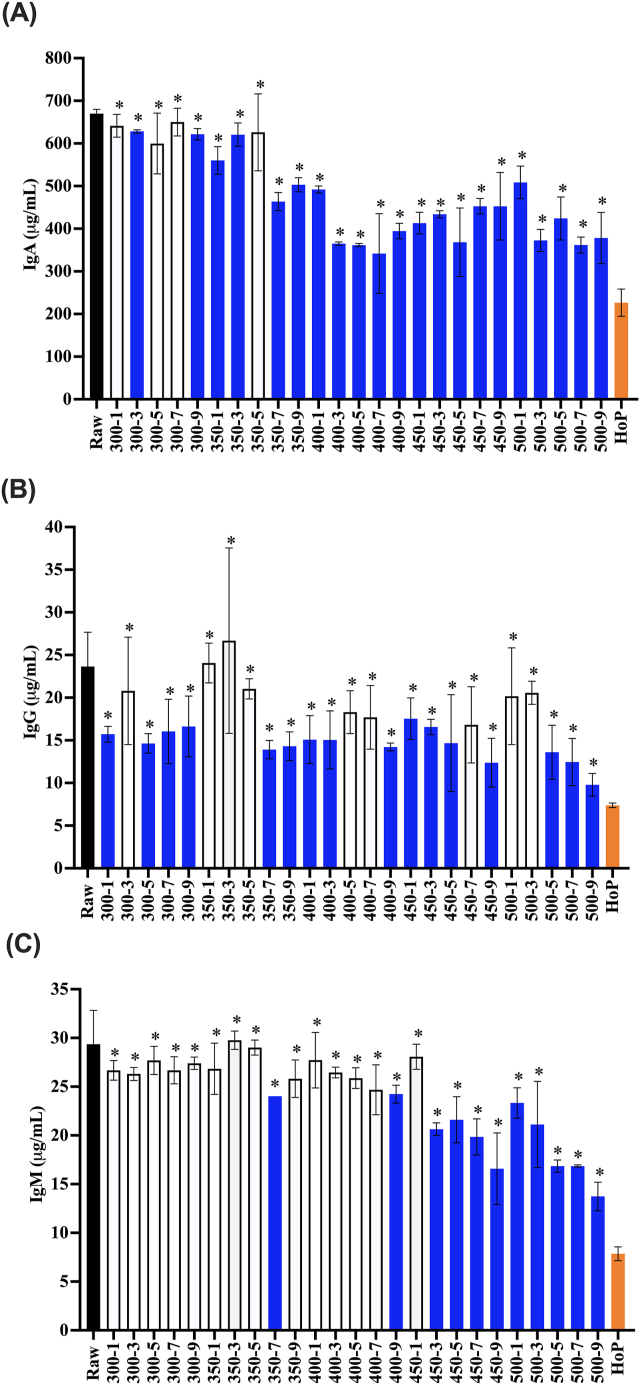

ELISA-detectable levels of IgA in human milk were significantly reduced by HoP, with only 33.8 ± 4.8% retention following the thermal treatment (Figure 4A). ELISA-detectable IgA levels were not impacted by HPP treatments at 300 MPa for 1, 5, and 7 min or 350 MPa for 5 min (Figure 4A). IgA levels were significantly reduced compared with raw milk by the majority of HPP treatments, including those with longer holding times (300 MPa, 9 min and 350 MPa, 7 min and beyond) as well as at all higher pressures (400 MPa and higher). The retention of IgA was significantly higher for all HPP treatments compared with HoP, with 56.4 ± 9.0% retention following the most extreme HPP treatment (500 MPa, 9 min).

FIGURE 4.

Antibody concentrations ((A): IgA, (B): IgG, and (C): IgM) in raw, HPP (300–500 MPa, 1–9 min), and HoP-treated donor milk. HPP treatments are labeled on the x-axis with the pressure followed by treatment time (for example, 300-1 indicates 300 MPa, 1 min). Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± SD. The black bar represents the raw milk. The orange bar represents the HoP-treated milk. Blue bars indicate HPP treatments that resulted in a significantly reduced concentration of detectable antibody compared with raw milk (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05). ∗ indicates donor milk treated with HPP with significantly higher retention of antibodies compared with HoP (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05).

Compared with raw milk, the HoP treatment significantly reduced native IgG. IgG concentrations were more variable in their response to the HPP treatment (Figure 4B). Though the 500 MPa for 9 min HPP treatment reduced IgG in comparison with the raw milk (41.4±5.6% retention), this retention was significantly higher than that with HoP (31.2 ± 1.2%).

The IgM concentration in HoP-treated milk was significantly lower than that in raw milk. The HoP treatment retained 26.7 ± 2.4% of IgM, which was significantly lower than raw milk. The concentrations of IgM were comparable to raw donor milk after nearly all treatments at 300 MPa, 350 MPa up to 5 min, and 400 MPa up to 7 min (Figure 4C). HPP treatments at 500 MPa significantly reduced IgM concentrations compared with raw milk; however, these treatments afforded significantly more retention (46.8±5.0% after 500 MPa, 9 min) compared with HoP (26.7 ± 2.4% retention).

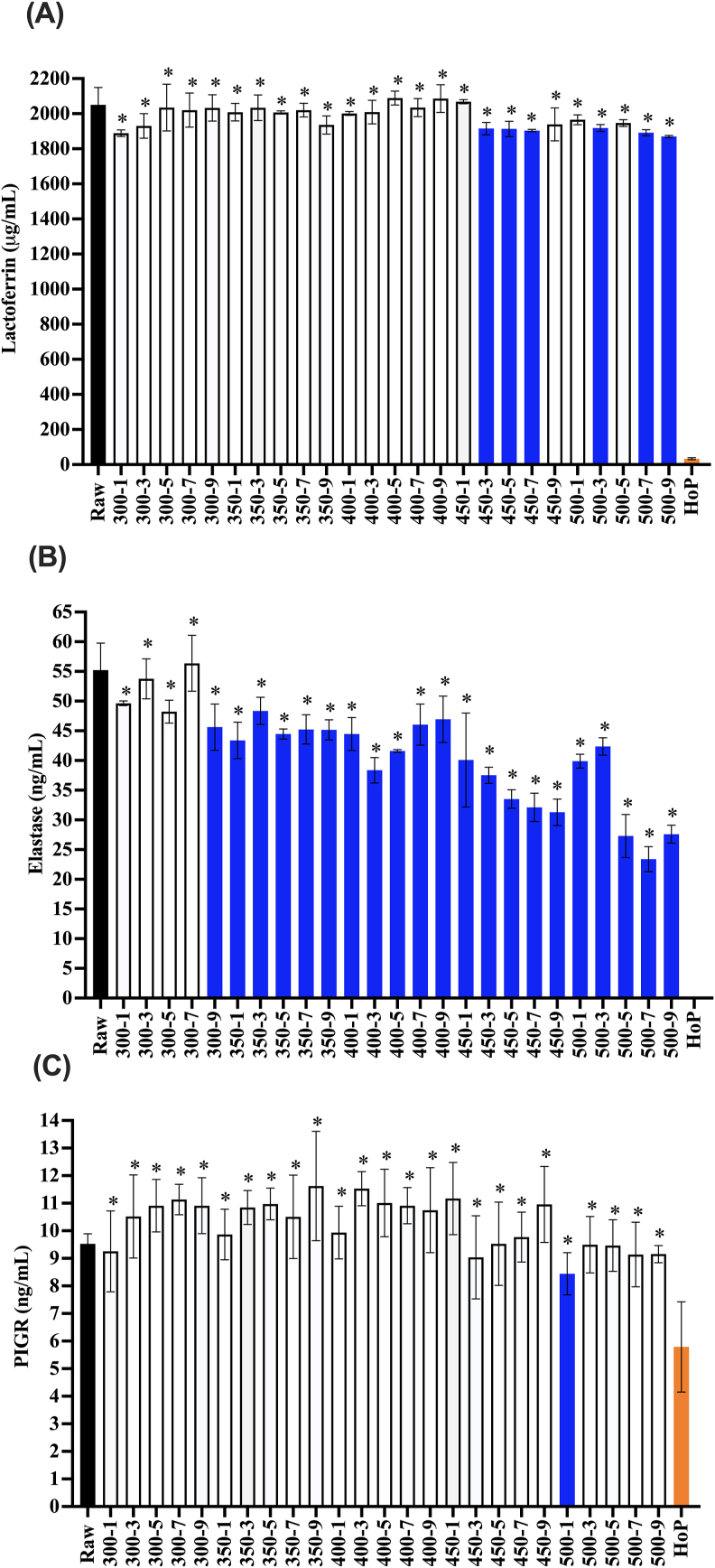

The HoP treatment retained 1.63 ± 0.27% ELISA-detectable lactoferrin (Figure 5A) compared with raw milk. Across all HPP treatments, there were only six treatments (450 MPa for 3, 5, and 7 min, 500 MPa for 3, 7, and 9 min), which caused a significant reduction in the lactoferrin concentration. The retention of ELISA-detectable lactoferrin in the milk sample was significantly higher after all HPP treatments tested than that after HoP (for example, 91.2 ± 0.32% after 500 MPa, 9 min).

FIGURE 5.

Lactoferrin (A), elastase (B), and polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) (C) concentration in raw milk, HPP-treated donor milk (300–500 MPa, 1–9 min), and HoP-treated donor milk. These proteins were grouped together because they were preserved better by HPP than HoP. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± SD. The black bar represents the raw milk. The orange bar9 represents the HoP-treated milk. Blue bars indicate HPP treatments that resulted in a significantly reduced concentration of detectable protein compared with raw milk (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05). ∗ indicates donor milk treated with HPP with significantly higher retention of proteins compared with HoP (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05).

Elastase was undetectable by ELISA after the HoP treatment in human milk samples (Figure 5B). HPP treatments at 300 MPa up to 7 min did not reduce elastase. The 500 MPa for 9 min treatment retained 50.0 ± 2.7% of elastase, which was significantly more than that retained by HoP.

The HoP treatment retained 60.8 ± 17.2% PIGR immunoreactivity in the milk samples (Figure 5C). Nearly all HPP treatments retained levels of PIGR immunoreactivity comparable to that of raw human milk with the exception being milk treated at 500 MPa, 1 min. All HPP treatments retained significantly more PIGR than that was retained by HoP.

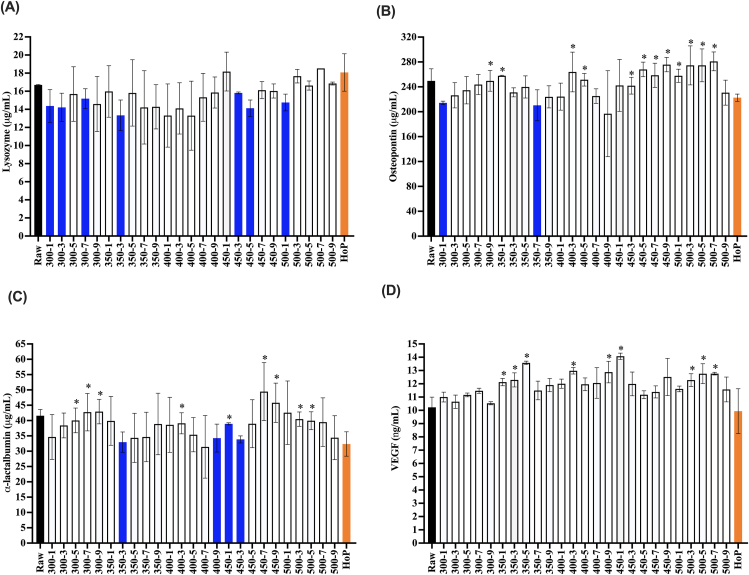

The HoP treatment retained all lysozyme (Figure 6A). Several HPP processing conditions (300 MPa for 1, 3, and 7 min, 350 MPa for 3 min, 450 MPa for 3 and 5 min, and 500 MPa for 1 min) resulted in moderately lower lysozyme retention (79.7–90.9%) compared with raw milk. The 500 MPa, 9 min treatment had no difference in lysozyme retention compared with that in raw milk (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Lysozyme (A), osteopontin (B), α-lactalbumin, (C) vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and (D) concentration in raw milk, HPP-treated donor milk (300–500 MPa, 1–9 min), and HoP-treated donor milk. These proteins are grouped together because they were preserved similarly by HoP and HPP. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± SD. The black bar represents the raw milk. The orange bar represents the HoP-treated milk. Blue bars indicate HPP treatments that resulted in a significantly reduced concentration of detectable protein compared with raw milk (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05). ∗ indicates donor milk treated with HPP with significantly higher retention of protein compared with HoP (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05).

The HoP treatment retained 89.2 ± 2.3% osteopontin immunoreactivity in the milk sample, which is significantly lower than that present in raw milk samples (Figure 6B). Only two HPP processing conditions (300 MPa for 1 min and 350 MPa for 7) caused moderate, but significant reduction in osteopontin immunoreactivity compared with that in raw milk. The strongest HPP treatment (500 MPa, 9 min) did not significantly reduce osteopontin immunoreactivity in human milk. The 500 MPa, 9 min treatment did not retain significantly more osteopontin than that was retained by HoP.

The HoP treatment retained 77.8 ± 9.6% α-lactalbumin immunoreactivity in the milk sample, which is significantly lower than that present in raw milk samples (Figure 6C). Only four HPP processing conditions (350 MPa, 3 min, 400 MPa, 9 min, and 450 MPa, 1 and 3 min) caused moderate, but significant reductions in α-lactalbumin retention (92.4 ± 9.8%, 82.4 ± 11.0%, 93.6 ± 0.8%, and 81.4 ± 2.8% retention) compared with that in raw milk. The strongest HPP treatment (500 MPa for 9 min) did not significantly reduce α-lactalbumin immunoreactivity in the milk sample. α-lactalbumin immunoreactivity was comparable after HoP and HPP at 500 MPa, 9 min.

HoP did not significantly reduce VEGF in comparison with raw milk (Figure 6D). No HPP processing condition caused significant decrease in VEGF in comparison with raw milk. A number of HPP processing conditions retained more VEGF immunoreactivity (17.4–37.6% higher; 350 MPa for 1, 3, 5, and 9 min, 400 MPa for 3 and 9 min, 450 MPa for 1 min, and 500 MPa for 3, 5, and 7 min) compared with HoP. For VEGF, HoP did not significantly differ from HPP at 500 MPa, 9 min (Figure 6D).

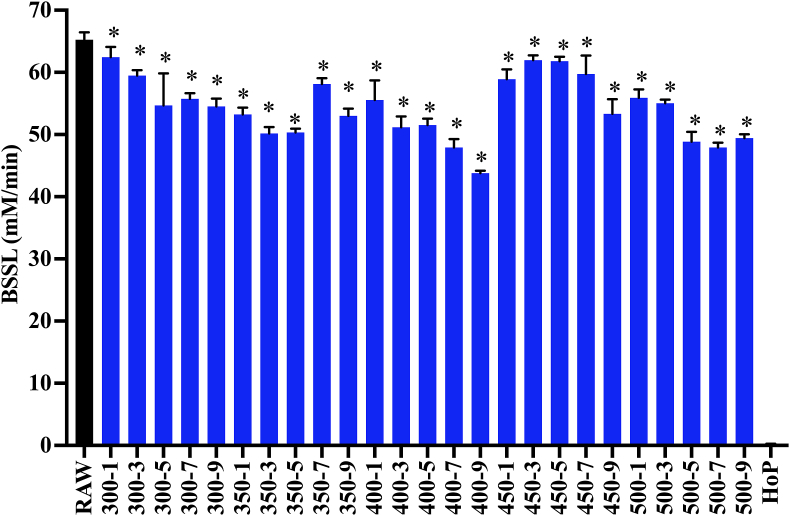

Our results indicate that the HoP treatment retained <1% of the BSSL activity in the milk sample (Figure 7). A small, but significant decrease in the BSSL activity was measured after the HPP treatment at 300 MPa for 3 min compared with the nontravel control (91.1 ± 1.3% retention). Extending the treatment time from 3 min to 5, 7, and 9 min did not cause further decrease in the BSSL activity. The lowest retention of the BSSL activity among the HPP treatments was observed at 400 MPa for 9 min (67.1 ± 0.6% retention). No further decrease in the BSSL activity was observed when increasing the pressure from 400 MPa to 500 MPa. 500 MPa for 9 min retained 75.7 ± 0.9% BSSL activity, which is significantly higher than that retained by HoP (<1%).

FIGURE 7.

Bile salt-stimulated lipase (BSSL) activity in samples in raw milk, HPP-treated donor (300–500 MPa, 1–9 min), and HoP-treated donor milk. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± SD. The black bar represents the raw milk. The orange bar represents the HoP-treated milk. Blue bars indicate HPP treatments that resulted in a significantly reduced concentration of detectable BSSL activity compared with raw milk (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05). ∗ indicates donor milk treated with HPP with significantly higher retention of BSSL activity compared with HoP (one-sided t-test; P < 0.05).

Discussion

This study is novel in that it is the first to inoculate bacteria and spores of interest into human milk followed by an array of HPP conditions to define specific log reductions and characterize the effects of these conditions on a large array of bioactive milk proteins.

Bacterial species differed in their sensitivities to HPP in human milk with C. sakazakii as the most pressure-sensitive and S. aureus as the most pressure-resistant. Our findings align with the general consensus that gram-positive bacteria are more resistant to the HPP treatment than gram-negative bacteria [[56], [57], [58]]. Others have reported that gram-type is less important than the cell shape with cocci being more resistant than bacilli [59]; however, these generalizations may be confounded by the limited studies on gram-negative cocci due to their limited significance in food systems. Regardless, there is consensus that gram-positive cocci are consistently the vegetative bacteria that are most resistant to HPP, which is further supported in this study by the comparable pressure resistance of E. faecium to S. aureus.

The lethal effect of HPP is considered to be predominantly a function of disruption of the selective permeability properties of the cellular membrane [60]. In bacteria, the cellular membrane is supported by an exterior peptidoglycan layer that dictates the shape and physical strength of the cell. This structure allows the bacteria to cope with stressors that impact the integrity of the cellular membrane [61], such as osmotic stress and pressure. A strong peptidoglycan layer may support the cellular membrane and prevent or limit changes in membrane permeability and/or pressure-induced phase inversions associated with HPP inactivation [62]. Gram-positive bacteria, especially S. aureus, possess thick (19–33 nm) peptidoglycan layers that likely play an important role in their increased resistance to HPP compared with gram-negative bacteria that have only a thin peptidoglycan layer (2.5–6.5 nm) [56,61,63]. HPP treatments are designed to compress every portion of the treated system in a uniform and hydrostatic manner, which results in an overall volume reduction due to the compressibility of the bulk pressure transducing fluid (typically a water–glycol mixture). Molecules and structures differ in their compressibility, but the cellular interior (i.e., cytoplasm) will likely decrease in a comparable manner. The decreased internal volume is predicted to result in a pressure decrease across the cell wall (due to loss of the sufficient turgor pressure) [59]. At pressures sufficient to cause changes in membrane permeability (>250 MPa), the cellular volume does not completely recover after the pressure is released, indicating a mass transfer to the exterior of the cell. This difference in the cellular volume pre- and post-HPP treatment has been demonstrated in S. aureus [64]. At higher pressures (500 MPa), the cell wall of S. aureus will eventually collapse [65], likely due to the difference in pressure between the interior and exterior of the cell. Further research is needed to thoroughly understand the physical properties that contribute to the HPP resistance of gram-positive cocci.

The HPP treatment of human milk at 500 MPa, 9 min resulted in >5-log reduction of all the vegetative neonatal pathogens tested in this study (C. sakazakii, L. monocytogenes, E. faecium, and S. aureus). As expected, bacterial spore populations were mostly unaffected (<1-log reduction) by the HPP treatment, even at the most extreme treatment (500 MPa, 9 min). This finding does not demonstrate inferiority to the standard HoP treatment used in donor milk banks as HoP is also ineffective at reducing bacterial spores. This ineffectiveness is evidenced by their common detection in human donor milk after pasteurization [37]. If sterility (i.e., spore inactivation) is a desired outcome of future donor milk processing, combinations of processing interventions and/or novel technologies would need to be evaluated. Pressure-assisted thermal processing (PATP; 70°C to >100°C) has been shown to effectively inactivate spores and can achieve sterility in low-acid food products, including milk [66]. However, PATP does result in the degradation of key vitamins, most significantly ascorbic acid, in bovine milk samples [67] and would likely cause the loss of many bioactive milk proteins. UV-C has also shown promise in its ability to sterilize foods. Historically, UV-C treatments have been applied to translucent liquids, primarily water and fruit juice; however, recent studies by our laboratory have found UV-C (8200 J/L) to be effective against bacterial spores in human milk when the treatment system is designed to maximize product exposure [40]. The efficacy of these processing approaches and their impact on the donor milk quality is being actively studied. Processing human milk with HPP at 500 MPa for 9 min would result in a comparable hazard reduction to that of HoP and reduce risk of infections associated with the feeding of contaminated donor milk, including neonatal sepsis associated with C. sakazakii and L. monocytogenes [68].

Food processing conditions should be validated using the pathogen of concern for that food matrix that demonstrates the highest degree of resistance to the chosen process [69,70]. Because of its demonstrated pressure resistance in human milk, S. aureus should be considered a suitable candidate target microorganism for the validation of future HPP treatments. Multiple studies have demonstrated comparable pressure resistance of S. aureus in human milk treated with HPP, further supporting this bacterium as a target pathogen. Windyga et al. [71] demonstrated minimal reductions (<2 log CFU/mL) of S. aureus ATCC 6538 in human milk treated with pressures of <400 MPa and significant reductions (>5 log CFU/mL) with pressure treatments at >500 MPa. Comparable results for the inactivation of S. aureus by HPP in human milk were reported with >500 MPa being necessary to achieve a >5-log reduction [72]. Longer holding times (>10 min) may support the use of lower pressures to inactivate S. aureus in human milk. Viazis et al. [50] and Jarzynka et al. [73] identified 400 MPa for 30 min and 450 MPa for 15 min as effective treatments for achieving the targeted >5-log reduction of S. aureus (ATCC 6538 and ATCC 33862, respectively) in human milk.

HPP induces conformational changes in proteins directly by the compression of proteins and indirectly via compression-induced changes in the properties of the bulk system that can interact with the conformation of proteins. Protein conformational changes due to the HPP treatment may be reversible or irreversible upon depressurization. In the current study, we quantified multiple key proteins in HPP-treated human milk using antibody-based methods (ELISA). After the application of our most extreme HPP treatment (500 MPa, 9 min), quantities of lysozyme, osteopontin, α-lactalbumin, VEGF, and PIGR remained similar to levels in raw donor milk, indicating minimal or reversible impact of pressure on these proteins. Previous studies have reported high barostability of lysozyme in human milk [53] and α-lactalbumin in bovine milk [74]. This study is the first to report the barostability of osteopontin, VEGF, and PIGR in human milk. Lactoferrin was significantly, but only minimally impacted by the HPP treatment (500 MPa, 9 min), with a reduction of only 9% compared with raw human milk. The barosensitivy of lactoferrin in human milk has been reported previously [53].

In contrast, following HPP (500 MPa, 9 min), antibodies (IgA, IgG, and IgM) and elastase were detectable by ELISA at approximately half (43–59%) of the quantity measured in raw human milk. Previous studies have reported similar reductions in antibodies following the HPP treatment of human milk [[75], [76], [77]]. No previous literature has examined the effect of HPP on human milk elastase. As the HPP treatment is not expected to cleave primary amino acid sequences, reductions in ELISA-detectable proteins demonstrates irreversible and sufficient changes in the conformational structure (because the specific antibodies used for capture and detection for each assay are specific for the intact structure of each protein) or aggregation (because the protein is either no longer present in the soluble protein fraction or no longer accessible to both antibodies due to complex formation). The retention of a protein observed via ELISA is an indicator that the structure is similar to the native form; however, the retention may not translate to a preserved function. Previous literature suggests that ELISA measurements often correlate with the retained protein function [78]; however, follow-up activity assays would be required for confirmation. Specific activity assays for many of the proteins examined herein have not been developed nor validated for use in human milk. The determination of protein-specific functions is complicated by the fact that multiple proteins in human milk can contribute to the same function. For example, many milk proteins (for example, lactoferrin, lysozyme, immunoglobulins) can contribute to the antimicrobial activity. Another approach would be the isolation and evaluation of specific proteins; however, extraction processes may alter the protein structure, thus limiting the ability of this approach to isolate the impact of milk processing technologies.

To evaluate the impact of HPP on BSSL, we took a different strategy to evaluate changes in the functionality of this enzyme using an activity assay. The BSSL assay is based on enzyme activity on a synthetic colorimetric probe (p-nitrophenyl myristate) [79]. Because of the specificity of the probe, this assay does not require extraction of BSSL from milk. The BSSL activity was significantly diminished following the HoP treatment; however, the activity of this nutritionally critical enzyme was highly retained at 70% or higher after all HPP treatments. This moderate loss in the BSSL activity following HPP was comparable to our previous study using a treatment of 550 MPa, 5 min [40].

Proteins differ in their resiliency to HPP depending on their physical structure and volumetric density [80]. Voids (empty space in the interior of a protein that are inaccessible to solvent) and cavities (empty space that is accessible to solvent) in the native protein structure can influence the sensitivity of a protein to pressure-induced unfolding [81]. The presence of large voids and cavities reduces a protein’s barostability [82]. Secondary structures of proteins also play a role in the barostability of proteins. Specifically, pressure treatments cause more disruption to α-helices than to β-sheets; therefore, the proportion of β-sheets to α-helices may be a decent predictor of barostability [83]. Predicting the pressure sensitivity of a protein is complex, as this sensitivity is affected by many other factors, such as intramolecular hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions and disulfide bond formation [84]. As conformational changes occur under pressure, newly exposed portions of the protein may interact with other proteins or bulk system components, which may lead to aggregation or other phenomena that impact their detection and/or functionality [85]. Further research is warranted to better understand and predict the impact of pressure on protein folding and function.

An overarching aim of this study was to identify an HPP treatment for human milk that would result in comparable safety and improved nutritional quality compared with the industry standard HoP treatment. Thermal treatments are well known for their ability to denature proteins, and proteins differ in their denaturation temperature. There are databases and tools available for predicting the protein response to the thermal treatment [86]. The HoP treatment effectively eliminates lactoferrin, elastase, and BSSL in human milk and causes significant decreases in antibodies (IgA, IgG, and IgM) and PIGR. This reduction of antibodies, BSSL, and elastase in human milk treated with HoP has been previously demonstrated [40,50,75,87,88]. Prior studies have observed reductions in lactoferrin [53,88], however, not as extreme as in the current study.

The HPP processing condition achieving targeted safety goals (500 MPa, 9 min) resulted in significantly improved retention of antibodies (IgA, IgG, and IgM), lactoferrin, elastase, PIGR, and BSSL. Lysozyme and osteopontin levels were unaffected by HoP or HPP treatment, confirming their thermal resistance reported in previous studies [88,89]. α-lactalbumin and VEGF levels were also unaffected by HoP in the current study. However, a previous study reported a significant reduction of osteopontin and an increased detection of α-lactalbumin in vat pasteurized human milk [88]. Previous studies have reported improved protein retention for HPP compared with HoP for lactoferrin [53] and BSSL [40]. Contador et al. demonstrated significant improvements in IgA and IgM retention for human milk treated at 400 MPa (3 and 6 min) compared with HoP; however, human milk treated at higher pressure (600 MPa) had antibody levels that were comparable to HoP. IgM levels in that study were the lowest for HoP; however, there was not a statistical improvement in retention for any of the HPP treatments [75]. This study is the first to compare the retention of elastase, osteopontin, α-lactalbumin, VEGF, and PIGR in human milk treated with HPP and HoP. These data provide strong evidence that HPP-treated human milk could enhance infant health outcomes. Improved immunoglobulin and lactoferrin levels could enhance protection of the infant against pathogenic bacteria and viruses [17,90]. Higher retention of elastase could enhance protein digestion and the production of bioactive peptides within the infant gut [91] and help protect against microbial pathogens [92]. Improved BSSL activity in donor human milk could enhance infant lipid digestion, absorption, and growth [40].

A potential limitation of this study is that we used a single large pool of donor human milk. The effects of processing could vary between milk samples and thus should be examined in future studies. However, the milk used herein was collected from a large number of donors to ensure that it was representative of typical donor milk. Moreover, we also conducted both our HPP and HoP treatments in triplicate on different days to account for potential interday variability. Using a single pool of milk also minimized any variation in the bioactive components that were measured, allowing for better detection of differences among treatments.

Currently, donor milk banks lack processing strategies for processing human milk to enhance safety while maintaining the bioactive protein structure. Overall, the current study addressed this critical knowledge gap by examining the extent to which the HPP treatment of milk can inactivate pathogens and preserve bioactive proteins compared with HoP. Our systematic analysis of a large array of bioactive proteins provides information on the impact of HPP on these components. This work also provides evidence suggesting that the HPP treatment at 500 MPa for 9 min of milk can result in a >5-log reduction in vegetative neonatal pathogens while preserving some key bioactive proteins (IgA, IgG, IgM, lactoferrin, elastase, PIGR, and BSSL) better than HoP. Future studies should investigate other alternative processing methods that can inactivate spore-forming bacteria. Producing donor human milk with preserved bioactivity may provide additional benefits to the recipient preterm infants compared with the current HoP treatment. This information will be valuable for neonalogists and donor milk processors and could support regulatory approval and commercial implementation of HPP for this critical infant food. Future clinical trials are warranted to further investigate the potential benefits of HPP-treated milk in terms of digestibility and health outcomes (i.e., growth, fat absorption, better protection against infection).

Author contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—All authors: contributed to the design of experiments; NL, HMHM, BJK, SB, AL: conducted the physical research; NL, HMHM, JW-C: analyzed data; NL, HMHM, BJK, JW-C, DCD: drafted and edited the paper and had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

NL, HMHM, BJK, SB, AL, JW-C, and DCD declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (grant no. 5R01HD106140).

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Michael A. Pitino and Md. Abdul Wazed for their thoughtful comments toward improving out manuscript. This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (grant no. 5R01HD106140). The Northwest Mother’s Milk Bank provided all donor milk used in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.07.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Arslanoglu S., Ziegler E.E., Moro G.E. World Association of Perinatal Medicine Working Group on Nutrition. Donor human milk in preterm infant feeding: evidence and recommendations. J. Perinat. Med. 2010;38(4):347–351. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menon G., Williams T.C. Human milk for preterm infants: why, what, when and how? Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 2013;98(6):F559–F562. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vohr B.R., Poindexter B.B., Dusick A.M., McKinley L.T., Higgins R.D., Langer J.C. Persistent beneficial effects of breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of age. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e953–e959. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singhal A., Cole T.J., Lucas A. Early nutrition in preterm infants and later blood pressure: two cohorts after randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357(9254):413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck K.L., Weber D., Phinney B.S., Smilowitz J.T., Hinde K., Lönnerdal B. Comparative proteomics of human and macaque milk reveals species-specific nutrition during postnatal development. J. Proteome. Res. 2015;14(5):2143–2157. doi: 10.1021/pr501243m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer D.J., Kelly V.C., Smit A.M., Kuy S., Knight C.G., Cooper G.J. Human colostrum: identification of minor proteins in the aqueous phase by proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6(7):2208–2216. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picariello G., Ferranti P., Mamone G., Klouckova I., Mechref Y., Novotny M.V. Gel-free shotgun proteomic analysis of human milk. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1227:219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidsson L., Kastenmayer P., Yuen M., Lönnerdal B., Hurrell R.F. Influence of lactoferrin on iron absorption from human milk in infants. Pediatr. Res. 1994;35(1):117–124. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199401000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lönnerdal B., Glazier C. Calcium binding by alpha-lactalbumin in human milk and bovine milk. J. Nutr. 1985;115(9):1209–1216. doi: 10.1093/jn/115.9.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren J., Stuart D.I., Acharya K.R. Alpha-lactalbumin possesses a distinct zinc binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268(26):19292–19298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindquist S., Hernell O. Lipid digestion and absorption in early life: an update. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2010;13(3):314–320. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328337bbf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demers-Mathieu V., Nielsen S.D., Underwood M.A., Borghese R., Dallas D.C. Changes in proteases, antiproteases, and bioactive proteins from mother’s breast milk to the premature infant stomach. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018;66(2):318–324. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold R.R., Brewer M., Gauthier J.J. Bactericidal activity of human lactoferrin: sensitivity of a variety of microorganisms. Infect. Immun. 1980;28(3):893–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.893-898.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bullen J.J., Rogers H.J., Leigh L. Iron-binding proteins in milk and resistance to Escherichia coli infection in infants. Br. Med. J. 1972;1(5792):69–75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5792.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel H.J. Lactoferrin, a bird’s eye view. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012;90(3):233–244. doi: 10.1139/o2012-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maga E.A., Cullor J.S., Smith W., Anderson G.B., Murray J.D. Human lysozyme expressed in the mammary gland of transgenic dairy goats can inhibit the growth of bacteria that cause mastitis and the cold-spoilage of milk. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2006;3(4):384–392. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lönnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in human milk: health, nutrition, and implications for infant formulas. J. Pediatr. 2016;173(Suppl):S4–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adkins Y., Lönnerdal B. Potential host-defense role of a human milk vitamin B-12-binding protein, haptocorrin, in the gastrointestinal tract of breastfed infants, as assessed with porcine haptocorrin in vitro. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;77:1234–1240. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe M., Oliveira G., Oda J., Ono M., Guembarovski R. Cytokines in human breast milk: immunological significance for newborns. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012;8(1):2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashkar S., Weber G.F., Panoutsakopoulou V., Sanchirico M.E., Jansson M., Zawaideh S., et al. Eta-1 (osteopontin): an early component of type-1 (cell-mediated) immunity. Science. 2000;287(5454):860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dvorak B., Fituch C.C., Williams C.S., Hurst N.M., Schanler R.J. Concentrations of epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha in preterm milk. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2004;554:407–479. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito S., Yoshida M., Ichijo M., Ishizaka S., Tsujii T. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) in human milk. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1993;94(1):220–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb06004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brock J.H. Lactoferrin in human milk: its role in iron absorption and protection against enteric infection in the newborn infant. Arch. Dis. Child. 1980;55(6):417–421. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donovan S.M., Atkinson S.A., Whyte R.K., Lönnerdal B. Partition of nitrogen intake and excretion in low-birth-weight infants. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1989;143(12):1485–1491. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150240107029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schanler R.J., Goldblum R.M., Garza C., Goldman A.S. Enhanced fecal excretion of selected immune factors in very low birth weight infants fed fortified human milk. Pediatr. Res. 1986;20(8):711–715. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unger S., Gibbins S., Zupancic J., O’Connor D.L. DoMINO: Donor milk for improved neurodevelopmental outcomes. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill P.D., Aldag J.C., Chatterton R.T., Zinaman M. Comparison of milk output between mothers of preterm and term infants: the first 6 weeks after birth. J. Hum. Lact. 2005;21(1):22–30. doi: 10.1177/0890334404272407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wight N.E. Donor human milk for preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2001;21(4):249–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delgado S., Arroyo R., Jiménez E., Marin M.L., del Campo R., Fernández L. Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from breast milk of women suffering infectious mastitis: potential virulence traits and resistance to antibiotics. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang M.S., Cheng C.C., Tseng S.Y., Lin Y.L., Lo H.M., Chen P.W. Most commensally bacterial strains in human milk of healthy mothers display multiple antibiotic resistance. Microbiologyopen. 2019;8 doi: 10.1002/mbo3.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heikkilä M.P., Saris P.E.J. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by the commensal bacteria of human milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;95(3):471–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Togo A.H., Dubourg G., Camara A., Konate S., Delerce J., Andrieu C., et al. Listeria monocytogenes in human milk in Mali: a potential health emergency. J. Infect. 2020;80(1):121–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lachowska M., Izdebski R., Urbanowicz P., Żabicka D., Królak-Olejni B. Infection of Cronobacter sakazakii ST1 producing SHV-12 in a premature infant born from triplet pregnancy. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1878. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wajda Ł., Ostrowski A., Błasiak E., Godowska P. Enterococcus faecium isolates present in human breast milk might be carriers of multi-antibiotic resistance genes. Bacteria. 2022;1(2):66–87. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin-Gómez W.M., Grande J., Pérez-Pulido R., Galvez A., Lucas R. Changes in the bacterial diversity of human milk during late lactation period (weeks 21 to 48) Foods. 2020;9(9):1184. doi: 10.3390/foods9091184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kontopodi E., Hettinga K., Stahl B., van Goudoever J.B., van Elburg R.M. Testing the effects of processing on donor human milk: analytical methods. Food Chem. 2022;373:131413. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landers S., Updegrove K. Bacteriological screening of donor human milk before and after Holder pasteurization. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:117–121. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jandová M., Měřička P., Fišerová M., Landfeld A., Paterová P., Hobzová L., et al. Bacillus cereus as a major cause of discarded pasteurized human banked milk: a single human milk bank experience. Foods. 2021;10:2955. doi: 10.3390/foods10122955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanson M.L., Wendorff W.L., Houck K.B. Effect of heat treatment of milk on activation of Bacillus spores. J. Food Prot. 2005;68:1484–1486. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.7.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh J., Victor A.F., Howell M.L., Yeo J.G., Qu Y., Selover B., et al. Bile salt-stimulated lipase activity in donor breast milk influenced by pasteurization techniques. Front. Nutr. 2020;7:552362. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.552362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silvestre D., Miranda M., Muriach M., Almansa I., Jareño E., Romero F.J. Antioxidant capacity of human milk: effect of thermal conditions for the pasteurization. Acta. Paediatr. 2008;97(8):1070–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulaviciene I.J., Liubsys A., Eidukaite A., Molyte A., Tamuliene L., Usonis V. The effect of prolonged freezing and Holder pasteurization on the macronutrient and bioactive protein compositions of human milk. Breastfeed. Med. 2020;15:583–588. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demazeau G., Plumecocq A., Lehours P., Martin P., Couëdelo L., Billeaud C. A new high hydrostatic pressure process to assure the microbial safety of human milk while preserving the biological activity of its main components. Front. Public Health. 2018;6:306. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Espinosa-Martos I., Montilla A., de Segura A.G., Escuder D., Bustos G., Pallás C., et al. Bacteriological, biochemical, and immunological modifications in human colostrum after Holder pasteurisation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013;56:560–568. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31828393ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guerra A.F., Mellinger-Silva C., Rosenthal A., Luchese R.H. Hot topic: Holder pasteurization of human milk affects some bioactive proteins. J. Dairy Sci. 2018:2814–2818. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson Y., Sävman K., Bläckberg L., Hernell O. Pasteurization of mother’s own milk reduces fat absorption and growth in preterm infants. Acta. Paediatr. 2007;96(10):1445–1449. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brownell E.A., Matson A.P., Smith K.C., Moore J.E., Esposito P.A., Lussier M.M. Dose-response relationship between donor human milk, motherʼs own milk, preterm formula, and neonatal growth outcomes. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018;67:90–96. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colaizy T.T., Carlson S., Saftlas A.F., Morriss F.H. Growth in VLBW infants fed predominantly fortified maternal and donor human milk diets: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montjaux-Régis N., Cristini C., Arnaud C., Glorieux I., Vanpee M., Casper C. Improved growth of preterm infants receiving mother’s own raw milk compared with pasteurized donor milk. Acta. Paediatr. 2011;100:1548–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viazis S., Farkas B.E., Jaykus L.A. Inactivation of bacterial pathogens in human milk by high pressure processing. J. Food Prot. 2008;71:109–118. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farkas D.F., Hoover D.G. High pressure processing. J. Food Sci. 2000;65(s8):47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peila C., Emmerik N.E., Giribaldi M., Stahl B., Ruitenberg J.E., van Elburg R.M., et al. Human milk processing: a systematic review of innovative techniques to ensure the safety and quality of donor milk. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017;64:353–361. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pitino M.A., Unger S., Doyen A., Pouliot Y., Aufreiter S., Stone D., et al. High hydrostatic pressure processing better preserves the nutrient and bioactive compound composition of human donor milk. J. Nutr. 2019;149(3):497–504. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durak M.Z., Fromm H.I., Huck J.R., Zadoks R.N., Boor K.J. Development of molecular typing methods for Bacillus spp. and Paenibacillus spp. Isolated from fluid milk products. J. Food Sci. 2006;71(2):M50–M56. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iida K.I., Amako K., Takade A., Ueda Y., Yoshida S.I. Electron microscopic examination of the dormant spore and the sporulation of Paenibacillus motobuensis strain MC10. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;51(7):643–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arroyo G., Sanz P.D., Préstamo G. Effect of high pressure on the reduction of microbial populations in vegetables. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1997;82(6):735–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell N.J. Bacterial membranes: the effects of chill storage and food processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002;79(1–2):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.G. Ramanna, P.P. Srivastav, Chapter 14. Non-thermal food processing by high hydrostatic pressure and pulse electric field: microbiology. Recent Advances in Microbiology. 1:261–286. Editors: S. P. Tiwari, R. Sharma, R. K. Singh. Nova Biomedical. India.

- 59.Hartmann C., Mathmann K., Delgado A. Mechanical stresses in cellular structures under high hydrostatic pressure. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2006;7(1–2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patterson M.F., Ledward D.A., Rogers N. In: Food Processing Handbook. Brennam J.G., editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheins, Germany: 2006. High Pressure Processing, chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 61.A. Walter, C. Mayer, Peptidoglycan structure, biosynthesis, and dynamics during bacterial growth, In: E. Cohen, H. Merzendorfer, Extracellular Sugar-Based Biopolymers Matrices. Biologically-Inspired Systems, vol. 12. Springer Nature. Switzerland.

- 62.Kato M., Hayashi R. Effects of high pressure on lipids and biomembranes for understanding high-pressure-induced biological phenomena. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999;63(8):1321–1328. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Auer G.K., Weibel D.B. Bacterial cell mechanics. Biochemistry. 2017;56(29):3710–3724. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pilavtepe-Celik M., Balaban M.O., Alpas H., Yousef A.E. Image analysis based quantification of bacterial volume change with high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Sci. 2008;73(9):M423–M429. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang B., Shi Y., Xia X., Xi M., Wang X., Ji B., et al. Inactivation of foodborne pathogens in raw milk using high hydrostatic pressure. Food Control. 2012;28(2):273. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang D., Zhang L., Wang X., Wang P., Liao X., Wu X., et al. Building of pressure-assisted ultra-high temperature system and its inactivation of bacterial spores. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1275. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de la Cruz Quiroz R., Chotyakul N., Saraiva J.A., Lamela C.P., Torres J.A. Retention of ascorbic acid, retinol, β-carotene, and α-tocopherol in milk subjected to pressure-assisted thermal processing (PATP) Food Eng. Rev. 2021;13:634–641. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zou M., Yang J., Wiechers C., Huehn J. Acute neonatal Listeria monocytogenes infection causes long-term, organ-specific changes in immune cell subset composition. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp). 2020;10(2):98–106. doi: 10.1556/1886.2020.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods Parameters for determining inoculated pack/challenge study protocols. J. Food Prot. 2010;73(1):140–203. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-73.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ceylan E., Amezquita A., Anderson N., Betts R., Blayo L., Garces-Vega F., et al. Guidance on validation of lethal control measures for foodborne pathogens in foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20(3):2825–2881. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Windyga B., Rutkowska M., Sokołowska B., Skąpska S., Wesołowska A., Wilińska M., et al. Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and native microflora in human milk by high pressure processing. High Press Res. 2015;35(2):181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rocha-Pimienta J., Martillanes S., Ramírez R., Garcia-Parra J., Delgado-Adamez J. Bacillus cereus spores and Staphylococcus aureus sub. aureus vegetative cells inactivation in human milk by high-pressure processing. Food Control. 2020;113:107212. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jarzynka S., Strom K., Barbarska O., Pawlikowska E., Minkiewicz-Zochniak A., Rosiak E., et al. Combination of high-pressure processing and freeze-drying as the most effective techniques in maintaining biological values and microbiological safety of donor milk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(4):2147. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marciniak A., Suwal S., Britten M., Pouliot Y., Doyen A. The use of high hydrostatic pressure to modulate milk protein interactions for the production of an alpha-lactalbumin enriched-fraction. Green Chem. 2018;20(2):515–524. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Contador R., Delgado-adámez J., José F., Cava R., Ramírez R. Effect of thermal pasteurisation or high pressure processing on immunoglobulin and leukocyte contents of human milk. Int. Dairy J. 2013;32(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Permanyer M., Castellote C., Ramirez-Santana C., Audi C., Pérez-Cano F.J., Castell M., et al. Maintenance of breast milk immunoglobulin A after high-pressure processing. J. Dairy Sci. 2010;93:877–883. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wesolowska A., Sinkiewicz-Darol E., Barbarska O., Strom K., Rutkowska M., Karzel K., et al. New achievements in high-pressure processing to preserve human milk bioactivity. Front. Pediatr. 2018;6:323. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sah B.N.P., Lueangsakulthai J., Kim B.J., Hauser B.R., Woo Y., Olyaei A., et al. Partial degradation of recombinant antibody functional activity during infant gastrointestinal digestion: implications for oral antibody supplementation. Front. Nutr. 2020;7:130. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Albro P.W., Hall R.D., Corbett J.T., Schroeder J. Activation of nonspecific lipase (EC 3.1.1.–) by bile salts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;835:477–490. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roche J., Royer C. Lessons from pressure denaturation of proteins. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2018;15(147):180244. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2018.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen C.R., Makhatadze G.I. Protein volume: calculating molecular van der Waals and void volumes in proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:101. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0531-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nucci N., Fuglestad B., Athanasoula E., Wand A. Role of cavities and hydration in the pressure unfolding of T4 lysozyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(38):13846–13851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410655111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gross M., Jaenicke R. Proteins under pressure: the influence of high hydrostatic pressure on structure, function, and assembly of proteins and protein complexes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;221:617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Galazka B., Dickinson E., Ledward D. Influence of high pressure processing on protein solutions and emulsions. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 2000;5(3–4):182–187. [Google Scholar]

- 85.G. Hummer, S. Garde, A. García, M.E. Paulaitis, L. Pratt, The pressure dependence of hydrophobic interactions is consistent with the observed pressure denaturation of proteins, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95(4) 1552–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Ku T., Lu P., Chan C., Wang T., Lai S., Lyu P., et al. Predicting melting temperature directly from protein sequences, Comput. Biol. Chem. 2009;33(6):445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koenig A., de Albuquerque Diniz E.M., Barbosa S.F.C., Vaz F.A.C. Immunologic factors in human milk: the effects of gestational age and pasteurization. J. Hum. Lact. 2005;21(4):439–443. doi: 10.1177/0890334405280652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liang N., Koh J., Kim B.J., Ozturk G., Barile D., Dallas D.C. Structural and functional changes of bioactive proteins in donor human milk treated by vat-pasteurization, retort sterilization, ultra-high-temperature sterilization, freeze-thawing and homogenization. Front. Nutr. 2022;9:926814. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.926814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dussault N., Cayer M.-P., Landry P., de Grandmont M.-J., Cloutier M., Thibault L., Girard M. Comparison of the effect of Holder pasteurization and high-pressure processing on human milk bacterial load and bioactive factors preservation. 2021;72(5):756–762. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kell D.B., Heyden E.L., Pretorius E. The biology of lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein that can help defend against viruses and bacteria. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1221. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abdul Wazed M., Farid M. Denaturation kinetics and storage stability of osteopontin in reconstituted infant milk formula. Food Chem. 2022;379:132138. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Belaaouaj A., Kim K.S., Shapiro S.D. Degradation of outer membrane protein A in Escherichia coli killing by neutrophil elastase. Science. 2000;289(5482):1185–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.