Abstract

Youth (aged 15 to 29 years) account for one quarter of new HIV cases in Canada. Of those, men-who-have-sex-with-men make up one third to one half of new cases in that age range. Moreover, Indigenous youth are over-represented in the proportion of new cases. The use of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) significantly reduces the risk of HIV acquisition in adults. Its use was expanded to include youth over 35 kg by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018. However, PrEP uptake remains low among adolescents. Prescriber-identified barriers include lack of experience, concerns about safety, unfamiliarity with follow-up guidelines, and costs. This article provides an overview of PrEP for youth in Canada, and its associated safety and side effect profiles. Hypothetical case vignettes highlight some of the many demographics of youth who could benefit from PrEP. We present a novel flow diagram that explains the baseline workup, prescribing guidelines, and follow-up recommendations in the Canadian context. Additional counselling points highlight some of the key discussions that should be elicited when prescribing PrEP.

Keywords: Adolescent health, Counselling, HIV, Pre-exposure prophylaxis

BACKGROUND

HIV infection rates have remained stable in Canada in recent decades with youth (aged 15 to 29 years) accounting for 24% (531 cases, in 2011) of all new cases (1). Men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) make up over one third of new positive cases among youth aged 15 to 19 years, and more than half among youth aged 20 to 29 years (1). Moreover, the proportion of new HIV cases is overrepresented among Indigenous youth, who make up 3.5% of the population, but 34.3% of new cases, in 2011 (1).

The use of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TruvadaTM) as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV in adults by over 95% when taken consistently (2,3). Its use was expanded to include youth weighing >35 kg by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as announced in 2018 (4). Despite its proven efficacy and safety, the use of and/or access to PrEP has been relatively low among adolescents, and specifically those of racial and ethnic minorities (5). Other studies show that past negative interactions with physicians and skepticism about the healthcare system pose significant barriers to equitable access to PrEP (6).

Surveys of North American adult health care providers (HCPs) and adolescent medicine physicians reveal that the majority of practitioners are aware of PrEP, most are generally willing to prescribe it, but far fewer have actually ever done so (7,8). The main barriers preventing HCPs from prescribing PrEP include lack of experience in prescribing PrEP, concerns about safety and side effects, unfamiliarity with the guidelines for follow-up, and medication costs (9–11).

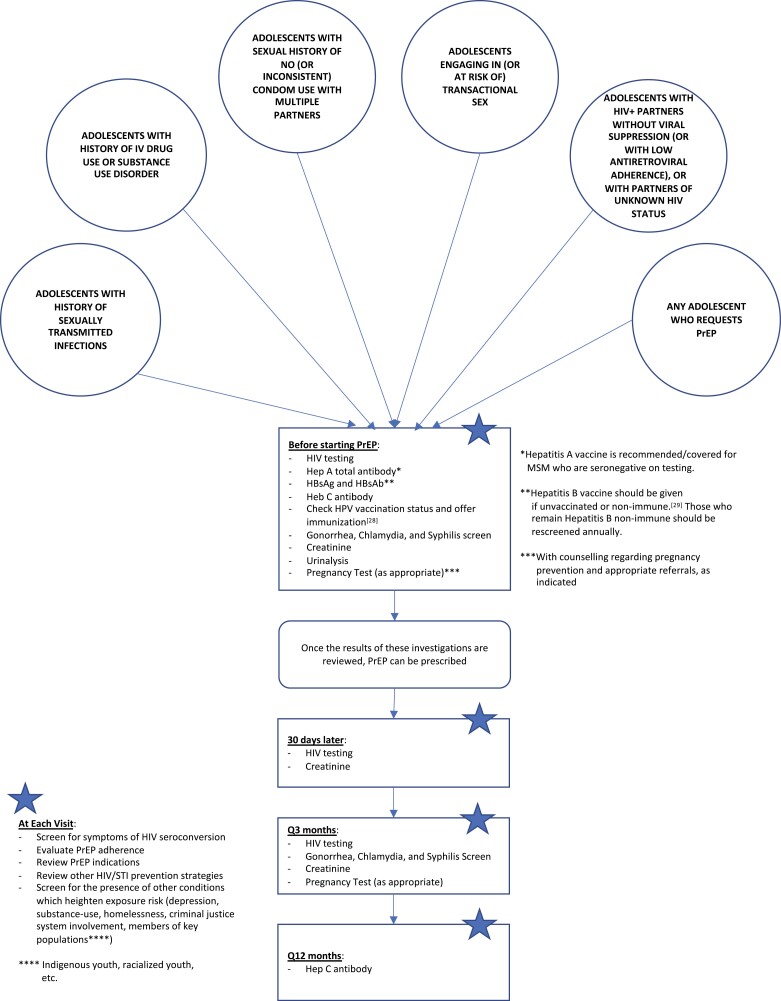

PrEP has mostly been targeted toward the adult MSM population, therefore information has not been directed at HCPs caring for adolescents, such as paediatricians and adolescent medicine providers. Given low awareness of PrEP amongst young people, emphasis should be placed on engaging adolescents in discussions around PrEP when assessing their sexual health needs. This is important for many adolescents (Figure 1), and particularly for high-risk groups including 2SLGBTQIA+ (two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual, non-binary and gender non-conforming) and racialized adolescents (1,12,13). The following vignettes provide some examples of adolescents from different demographics who could benefit from the use of PrEP:

Figure 1.

Algorithm for consideration of PrEP based on American (25,26) and Canadian (27) Guidelines for Eligibility, Initiation, and Monitoring.

Case #1: JOSEPH.

Joseph is a 16-year-old male who presents to his paediatrician for a vaccination visit without his parents. He shares that he identifies as bisexual or gay (he is unsure) and has been sexually active in the past year with multiple partners, aged 16 to 19 years, whom he had met online. Joseph is concerned about his risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). He discloses that he’s had several sexual encounters where condoms were not used. Although these were consensual encounters and he was not coerced to not use condoms, alcohol was involved, and he found it difficult to ‘keep track’ of condom use. He is requesting STI testing but is also interested in hearing about a medication he had read about online that could ‘stop me from getting HIV’. He asks if that is something he could get prescribed by the paediatrician but worries about his parents finding out, as they are not aware of him being sexually active or identifying as bisexual/gay. The paediatrician is unfamiliar with HIV PrEP, but recommends they start with STI screening and safer sex counseling. They offer Joseph a follow up appointment to provide him with more information about PrEP. They also connect him with the clinic social worker to discuss his concerns about sharing his sexuality with his parents.

Case #2: BELLA .

Bella is a 15-year -old youth who identifies as non-binary (assigned female at birth) who is seen in the Emergency Department (ED) of a children’s hospital following a sexual assault (SA). They report being assaulted by a man they met at a party, whom they had observed injecting drugs. This is Bella’s third such incident and they had previously been prescribed HIV and STI post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Bella is assessed by the social worker who is concerned that they may be a victim of sex trafficking and contacts Child Protection Services. The worker asks if there were any STI harm reduction measures available for Bella other than condoms. The ED physician recommends HIV and STI PEP and emergency contraception for today’s assault. They ask if Bella would be interested in a daily medication to reduce their risk of HIV infection. Bella is interested to hear more, though worries about how they would be able to access and adhere to it. The physician provides them with information and refers them back to Adolescent Health clinic for SA follow-up and further counselling regarding PrEPincluding adherence and privacy with respect to taking medication.

Case #3: DAKOTA.

Dakota is a 17-year-old Indigenous youth who comes in to see his family doctor for assessment. He identifies as two-spirit (born male, prefers he/him pronouns) and has sex with both males and females. A female partner had contacted him recently to inform him that she was diagnosed with gonorrhea. Dakota is experiencing dysuria and penile discharge and is concerned he has acquired gonorrhea. He reports feeling ‘freaked out’ as this is his second STI in the past two years, having been diagnosed with chlamydia last year. Additionally, his best friend was recently diagnosed with HIV, and he keeps hearing about the increased number of HIV cases in his community over the past few years. Dakota’s uncle died of HIV, and it left a big impression on him. The family doctor makes plans to test Dakota for gonorrhea and other STIs, provides empiric treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and asks him if he would like to hear more about a daily medication he can use to reduce his risk of HIV infection. Dakota is relieved and says he would like to hear more.

CURRENT OPTIONS

Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF)/Emtricitabine (FTC) 300/200 mg PO once daily (14)

Brand name: TruvadaTM (multiple generic formulations also available)

While the Canadian product labeling was not updated by the manufacturer following the FDA approval, the use of TDF/FTC as PrEP in adolescents is supported by two open label trials: ATN 113 (15) and CHAMPS PlusPills (16). Gilead’s decision was to not apply for Health Canada indication change, as it had already become generic by that point. It is also routinely used for the treatment of paediatric HIV infection.

Cost coverage varies across provinces and territories, but all regions have some degree of publicly funded coverage, as outlined by the table of coverage cited here (17). Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, Yukon, and those receiving Non-Insured Health Benefits all receive universal coverage, with the other provinces and territories full or shared coverage based on the rules of individual drug plans.

In Ontario, the list price for a month of TDF/FTC is approximately $220 (18).

An alternative schedule of on-demand dosing (two pills as a loading dose 2 to 24 hours before a sexual encounter, followed by another pill 24 hours later, and another pill 24 hours after that) has also been shown to be effective in preventing HIV infection (19), and may be considered an alternative PrEP option for certain youth. When compared with placebo, the point estimate for efficacy seen with on-demand dosing in the IPERGAY trial was similar to that seen in trials of daily dosing (19). However, no head-to-head comparison of the two regimens has been done. This schedule would be considered off-label use for adolescents. As this strategy has only been studied and shown to be effective in adult MSM, it cannot yet be recommended for use in people assigned female at birth.

*During ATN 113, more than 95% of participants had detectable drug levels over the first 12 weeks of treatment, but levels declined in the participant body, thereafter. While three participants acquired HIV during the trial, all were found to have sub-therapeutic drug levels (15). Eighteen percent of participants in the CHAMPS PlusPills trial stopped PrEP at 12 weeks and by 36 weeks 43% had stopped. In this trial, only one participant acquired HIV, but this participant had stopped PrEP 24 weeks prior to diagnosis (16).

**PEP ‘in pocket’ may be a suitable option for some youth with infrequent but high-risk exposures, but there is thus far relatively little published experience with this approach.

SAFETY IN ADOLESCENTS

TDF/FTC has been shown to be safe and well tolerated as PrEP for adolescents at risk of HIV acquisition in the aforementioned trials (15,16). Additionally, there were no safety concerns identified for the use of TDF/FTC during pregnancy (14).

Side effects and toxicity risks associated with TDF/FTC include:

Headache, abdominal pain, and decreased weight (14)

-

Risks of renal and skeletal toxicities (renal tubular dysfunction; reduced bone mineral density):

In adult PrEP trials, risk of renal impairment with TDF/FTC was not significantly increased compared to placebo and serum creatinine changes were reversed upon medication discontinuation (20). It is recommended that TDF/FTC should only be prescribed if the patient has normal baseline creatinine clearance (>60 mL/min or normal for age/sex) (14).

Prolonged treatment with TDF has been shown to reduce bone mineral density in adolescents living with HIV, though the impact of HIV itself on bone and whether there is greater drug toxicity on growing bone are not entirely clear. Bone mineral density decreases associated with PrEP were reversed upon medication discontinuation (21,22). The impact of specific interventions like vitamin D and calcium supplementation in adolescents are under active study. It is the authors’ view that radiographically assessing bone mineral density be reserved for those with other risk factors for osteopenia or those who develop fractures.

If concerns for bone health due to concurrent conditions and/or treatments (i.e., Depo-Provera, Lupron), consider pre-emptive bone health preservation strategies such as vitamin D supplementation of 400 to 1,000 IU per day.

ALTERNATIVE/FUTURE OPTIONS

-

Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF)/Emtricitabine (FTC) 25/200 mg PO once daily

Brand name: DescovyTM (23)

TAF is an alternative antiretroviral agent that leads to equivalent intracellular tenofovir concentrations but lower plasma exposure, resulting in reduced incidence of bone and renal toxicity.

Per Canadian product monograph: ‘The safety and efficacy of DESCOVY for HIV-1 PrEP in at-risk adolescents weighing ≥ 35 kg (excluding individuals at risk from receptive vaginal sex) is supported by data from an adequate and well-controlled trial of DESCOVY for HIV-1 PrEP in adults’ (23).

TAF/FTC is likely to gain popularity in the future as a PrEP option for youth.

At this point in time, cost remains a barrier to accessing Descovy. If patients are accessing PrEP via provincial funding (17) then generic TDF/FTC will be covered over Descovy.

-

Cabotegravir extended-release injectable suspension IM monthly ×2, then every 2 months (24)

Brand name: ApretudeTM

In December 2021, the FDA approved ApretudeTM for use in at-risk adults and adolescents weighing at least 35 kg (77 pounds) for PrEP to reduce the risk of sexually acquired HIV (24). It is not yet approved for use in Canada but will likely be approved in the coming few years. Once approved, this injectable form given every 2 months could be expected to improve adherence.

COUNSELLING POINTS

-

Regarding confidentiality, providers do NOT need to disclose prescription of PrEP to the adolescent’s parents/guardians

Be aware of the possibility of pharmacies calling parents/guardians regarding prescription medication coverage; alternative options for PrEP coverage should be explored with pharmacists and local PrEP providers to try to preserve confidentiality.

Some adolescents may be agreeable to their parents’ awareness and involvement in decision-making, which could simplify the drug coverage process for them.

Counsel that PrEP does not prevent against other sexually transmitted infections or pregnancy. Encourage consistent and correct condom use to help prevent STIs and/or pregnancy. Explore other contraception options (e.g., injectable, IUD) if there are challenges with consistent condom use for pregnancy prevention.

Adequate adherence is needed for PrEP to be efficacious. Providers should consider more frequent (e.g., monthly) follow-up for support, on a case-by-case basis, if there are concerns regarding potential low adherence. Decreased adherence has been demonstrated with decreased visit frequency (16).

If adolescents decide to continue using PrEP, it is recommended to screen for barriers to adherence (such as transportation issues and insurance changes) and to work with them to mitigate these barriers (30).

Employ substance use-related harm reduction measures as appropriate. Discuss the importance of not sharing drug injection equipment, provide information about needle exchange programs/safe injection sites, and provide referrals for addictions/detox programs if the patient is interested.

Trauma-informed care, gender-affirming care, and culturally safe care are paramount in discussions around PrEP and should inform discussions during ongoing care.

WHAT’S NEW.

Any licensed prescriber can prescribe HIV PrEP to adolescents. In fact, in the United States, paediatricians are the leading prescribers of PrEP for adolescents (31). However, it is reasonable to obtain advice from experienced PrEP providers if there are questions or concerns.

Daily oral Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine is indicated for any sexually active adolescent weighing at least 35 kg, who is at risk of HIV acquisition.

Baseline testing and monthly follow-up/monitoring are recommended for youth starting PrEP (Figure 1).

Adolescents should be engaged in discussion about their sexual practices and overall sexual health, including age-appropriate anticipatory guidance.

While MSM are the population in whom HIV infection rates are highest in Canada, racialized, Indigenous, and other high-risk youth must be identified and engaged in PrEP discussion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network Prevention Core’s National Adolescent PrEP Working Group who provided critical review of this document. Working group members include: Camille Arkell, Jason Brophy, Megan Cooney, Lindsay Fleming, Rosheen Grady, Megan Harrison, Allison Kirschbaum, Simone Lebeuf, Sean Leonard, Carmen Logie, Joshua Nash, Nancy Nashid, Vandana Rawal, Amy Robinson, Laura Sauvé, Tatiana Sotindjo, Darrell Tan, Ashley Vandermorris, Ellie Vyver, and Karla Wentzel. This work was provided in-kind administrative support by the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network.

Contributor Information

Sean Leonard, Department of Paediatrics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

Tatiana Sotindjo, Division of Adolescent Medicine and Division of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Jason Brophy, Division of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Darrell H S Tan, Division of Infectious Diseases, St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Nancy Nashid, Division of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

JB is Chair of the AIDS Committee of Ottawa and has a consulting contract with Merck Canada Inc. DHST’s institution has received investigator-initiated research grants from Abbvie and Gilead, and he is a Site Principal Investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Glaxo Smith Kline. He is also supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in HIV Prevention and STI Research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Public Health Agency of Canada. Population-Specific Status Report. HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted and blood borne infections among youth in CANADA. 2014: 33–38

- 2. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016;387(10013):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(10):1601–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Food and Drug Administration. HIV-1 PrEP drug can be part of a strategy to prevent infection in at-risk adolescents. AAP News 2018;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Mera Giler R, et al. The prevalence of PrEP use and the PrEP-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28(12):841–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Zarwell M, Pearson B, Lewis M.. “A gay man and a doctor are just like, a recipe for destruction”: How racism and homonegativity in healthcare settings influence PrEP uptake among young Black MSM. AIDS Behav 2019;23(7):1951–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: Implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019;33(12):507–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hart-Cooper GD, Allen I, Irwin CE Jr, Scott H.. Adolescent health providers’ willingness to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to youth at risk of HIV infection in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2018;63(2):242–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bekker LG.. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: Observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pina P, Taggart T, Sanchez Acosta M, Eweka I, Muñoz-Laboy M, Albritton T.. Provider comfort with prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2021;35(10):411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mullins TLK, Idoine CR, Zimet GD, Kahn JA.. Primary care physician attitudes and intentions toward the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in adolescents in one metropolitan region. J Adolesc Health 2019;64(5):581–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kann L, O’Malley Olsen E, McManus T, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12 — United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65(9):46–53. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/pdfs/ss6509.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) [Package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences Inc.; 2018. https://www.gilead.com/~/media/files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/truvada/truvada_pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hosek SG, Landovitz RJ, Kapogiannis B, et al. Safety and feasibility of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for adolescent men who have sex with men aged 15 to 17 years in the United States. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:1063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gill K, Dietrich J, Gray G, et al. PlusPills: An open label, safety and feasibility study of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 15–19 year old adolescents in two sites in South Africa [Abstract]. Presented at the 9th IAS Conference on HIV Science, Paris, France; July 23–26, 2017

- 17. Yoong, D. (2022, January). Provincial/Territorial Coverage of ARV drugs for HIV prevention across Canada: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). University Health Network Toronto General Hospital. https://hivclinic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022-Jan_ARV-access-for-PrEP.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). Ontario drug benefits formulary search: Emtricitabine & tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. 2018b. https://www.formulary.health.gov.on.ca/formulary/results.xhtml?q=truvada&type=2. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

- 19. Molina, JM, Capitant, C, Spire, B, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Allen E, Gordon A, Krakower D, Hsu K.. HIV preexposure prophylaxis for adolescents and young adults. Curr Opin Pediatr 2017;29:399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glidden DV, Mulligan K, McMahan V, et al. Brief report: Recovery of bone mineral density after discontinuation of tenofovir-based HIV preexposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kasonde M, Niska RW, Rose C, et al. Bone mineral density changes among HIV-uninfected young adults in a randomised trial of preexposure prophylaxis with tenofovir-emtricitabine or placebo in Botswana. PLoS One 2014;9:e90111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Descovy (emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) [Product Monograph]. Mississauga, ON: Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc.; 2020. https://www.gilead.ca/-/media/gilead-canada/pdfs/medicines/descovy_english_pm_e177688-gs-006.pdf?la=en&hash=2AA8C9ED288EBE387214CD5C5B6E2EB3 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Apretude (cabotegravir extended-release injectable suspension) [Package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215499s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). US public health service. preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 Update: A clinical practice guideline. pp. 13–7.

- 26. Whelihan JT, Novak M.. Pre-exposure prophylaxis—preventing HIV in adolescents. JAMA pediatrics 2021;175(12):1300–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan, DH, Hull, MW, Yoong, D, et al. Canadian guideline on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. CMAJ 2017;189(47):E1448–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Derstenfeld A, Cullingham K, Ran ZC, Litvinov IV.. Review of evidence and recommendation for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination of Canadian males over the age of 26 years. J Cutan Med Surg 2020;24(3):285–91. doi: 10.1177/1203475420911635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Public Health Agency of Canada. Hepatitis B vaccine: Canada immunization guide (2017).

- 30. Tanner MR, Miele P, Carter W, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for prevention of HIV acquisition among adolescents: Clinical considerations, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020;69(3):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hosek S, Henry-Reid L.. PrEP and adolescents: The role of providers in ending the AIDS epidemic. Pediatrics 2020;145(1):3–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]