Abstract

Using internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region ribosomal DNA sequences from 37 stock strains and clinical isolates provisionally termed Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex in Japan, we demonstrated the mutual phylogenetic relationships of these strains. Members of this complex were classified into 3 ITS1-homologous groups and 13 ITS1-identical groups by their sequences. ITS1-homologous group I consists of Arthroderma vanbreuseghemii, T. mentagrophytes human isolates, and several strains of T. mentagrophytes animal isolates. Five strains of Arthroderma simii form a cluster comprising ITS1-homologous group II. The Americano-European and African races of Arthroderma benhamiae, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei, and one strain of a T. mentagrophytes animal isolate constitute ITS1-homologous group III. According to the phylogenetic tree constructed with Trichophyton rubrum as an outgroup, ITS1-homologous groups I and II comprised a monophyletic cluster and ITS1-homologous group III constituted another cluster which was rather distant from the others in the complex. This system was applicable to the phylogenetic analysis of closely related strains. Using this technique, human and animal isolates of T. mentagrophytes were also clearly distinguishable from each other.

Dermatophytes have the capacity to invade keratinized tissues, that is, the skin, hair, and nails, of humans and other animals to produce an infection, dermatophytosis, referred to as ringworm or tinea. Trichophyton mentagrophytes (8) is known as a complex species (22) and is one of the major pathogens causing this infection (23). Using mating tests and microscopic observation of ascospores, three perfect fungal states of T. mentagrophytes have been identified in this imperfect or conidial “species.” They are Arthroderma vanbreuseghemii, Arthroderma simii, and Arthroderma benhamiae (1, 20, 22), the latter being classified into two races, American-European and African (21). The phylogeny of T. mentagrophytes, however, remains unclear because the phenotypic features of members of the T. mentagrophytes complex are poor and many isolates from medical and veterinary samples have lost their sexual activity (22). From a clinical point of view, because the T. mentagrophytes complex includes both anthrophilic and zoophilic species (23), it is important to have a reliable method of identifying the human-pathogenic species of the complex. Establishment of the phylogenetic classification of this complex has been achieved by molecular biological studies on the phylogeny of pathogenic fungi, primarily using the G+C content of chromosomal DNA (5), total DNA homology (6), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (7, 13, 17, 18), and the base sequence of the 18S (11) or 28S (14) rRNA or rRNA gene (rDNA). However, for dermatophytes, including T. mentagrophytes, the phylogenic relationship or species-specific sequences cannot be defined by these methods, because the members of this group of fungi are phylogenetically and taxonomically very closely related. Specific DNA sequences of the internal transcribed spacer 1 region (ITS1) of the rDNA in the T. mentagrophytes complex, mainly of strains stocked in Japan, were therefore determined and phylogenetically analyzed. ITS1 is located between the 18S and 5.8S rDNAs. As reported previously, the variable ITS regions have proven useful in resolving relationships between close taxonomic relatives (2, 3, 15). We were able to successfully differentiate between members of the T. mentagrophytes complex and a related species, Trichophyton rubrum, and to demonstrate their phylogenetic relationship by base pair comparisons of ITS1 regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

Standard strains of members of the T. mentagrophytes complex—A. vanbreuseghemii (two strains), A. simii (five strains), A. benhamiae (Americano-European race, two strains; African race, two strains), T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei (two strains)—and clinical isolates of T. mentagrophytes (five strains of human isolates and eight strains of animal isolates) were used in this study (Table 1). Clinical isolates of T. rubrum (eight strains of human isolates and three strains of animal isolates) were used as the outgroup. Six other pathogenic fungi, Microsporum canis TIMM0765, Penicillium marneffei IFM41707, Candida albicans ATCC10231, Candida glabrata TIMM1062, Trichosporon beigelii TIMM3140, and Mucor circinelloides TIMM1325, were used to show the wide applicability of the PCR primers described below. Clinical isolates were isolated in Japan and identified by their morphological features (for molds) or by using the Vitek Yeast Biochemical Card bioMerieux Vitek Inc.) (for yeasts).

TABLE 1.

Strains of T. mentagrophytes complex and T. rubrum used in this study

| Species | Straina | Source |

|---|---|---|

| A. vanbreuseghemii | VUT77007←SM110←RV27960 | |

| VUT77008←SM111←RV27961 | ||

| A. benhamiae | SM103←RV26678 | |

| Americano-European race | SM104←RV26680 | |

| African race | SM165←RV30000 | |

| SM166←RV30001 | ||

| A. simii | VUT77009←IMI101694 | |

| VUT77010←IMI101695 | ||

| SM160←CBS44865←IMI101693 | ||

| CBS520.75 | ||

| SM161←CBS150.66 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes | SM162←CBS34479 | |

| var. erinacei | SM163←CBS67786 | |

| Human clinical isolate | TIMM1187 | Janssen Pharmaceutical Research Laboratories |

| TIMM3246 | Nihon University Hospital | |

| TIMM3258 | Showa University Fujigaoka Hospital | |

| TIMM3282 | Showa University Hospital | |

| TIMM3295 | Showa University Fujigaoka Hospital | |

| Animal isolate | TLD0015←VUT75023 | Japanese deer |

| TLD0014←VUT74023 | Djungarian hamster | |

| TLD0017←VUT76001 | Rat | |

| TLD0019←VUT85002 | Golden hamster | |

| TLD0020←VUT4013 | Dog | |

| TLD0021 | Sea lion | |

| TLD0027 | Dog | |

| TLD0329 | Rabbit | |

| T. rubrum | ||

| Human clinical isolate | TIMM3223 | |

| TIMM3224 | ||

| TIMM3231 | ||

| TIMM3232 | ||

| TIMM3276 | ||

| TIMM3286 | ||

| TIMM3288 | ||

| TIMM3620 | ||

| Animal isolate | TLD0070 | Dog |

| TLD0078 | Dog | |

| TLD0080 | Dog |

All clinical isolates from humans and animals were obtained in Japan. CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands; IMI, International Mycological Institute, Surrey, United Kingdom; RV, Institute de Medicine Tropicale, Antwerp, Belgium; SM, Department of Dermatology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan; TIMM, Teikyo University Institute of Medical Mycology, Tokyo, Japan; TLD, Laboratory of Dermatology, School of Medical Science, Teikyo University; VUT, Department of Veterinary Internal Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

Preparation of DNA from fungal cells.

All fungal strains were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar (1% [wt/vol] peptone, 1% [wt/vol] glucose, 1.5% [wt/vol] agar) at 27 or 37°C for 1 to 5 days. Rapid preparation of DNA from molds was performed by a modification of the method described by Cenis (4). A small amount of mycelium grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar was placed in lysis buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA) and crushed with a conical grinder. It was incubated at 100°C for 15 min, mixed with 150 μl of 3.0 M sodium acetate, kept at −20°C for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was extracted once with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol) and subsequently extracted once with chloroform. DNA was precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol at −20°C for 10 min, washed with 0.5 ml of 99% ethanol, dried, and suspended in 50 μl of ultrapure water (Milli-Q Synthesis A10; Millipore). One microliter of the resulting solution was used as a template for PCR. The total time required to prepare the DNA was 80 min.

DNA from yeasts was rapidly prepared by a modification of the method described by Makimura et al. (16). A small part of a yeast colony was suspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer. After being mixed with a vortex mixer for 5 s, the sample was incubated at 100°C for 15 min. One hundred microliters of 3.0 M sodium acetate was added, and after being mixed, the preparation was incubated at −20°C for 10 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min, after which the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. DNA was precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol, washed with 0.5 ml of 99% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 100 μl of ultrapure water. One microliter of the resulting DNA solution was used as a PCR template.

Oligonucleotide design.

All oligonucleotides used in this study were designed based on comparison with the sequences of 18S and 5.8S rDNAs in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database (accession numbers of 18S rDNA sequences, M60302 [C. albicans], V01335 [Saccharomyces cerevisiae], M55625 [Cryptococcus neoformans], M55626 [Aspergillus fumigatus], X54863 [Mucor racemosus], M10098 [Homo sapiens); accession numbers of 5.8S rDNA sequences, U09327 [S. cerevisiae], J01359 [Schizosaccharomyces pombe], X02447 [Neurospora crassa], and AA470820 [H. sapiens]). The highly conserved sequences of all organisms were analyzed with GENETYX-MAC version 9.0 software (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and our newly designed oligonucleotide primers 18SF1 (5′-AGGTTTCCGTAGGTGAACCT-3′, bp 1764 to 1783 of the S. cerevisiae 18S rDNA) and 58SR1 (5′-TTCGCTGCGTTCTTCATCGA-3′, bp 53 to 34 of the S. cerevisiae 5.8S rDNA) were made by Pharmacia Biotech Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

PCR.

Each PCR mixture contained 10 μl of 10× reaction buffer (Pharmacia); 100 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (Pharmacia); 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Pharmacia); 30 pmol of each primer; and DNA template solution. Ultrapure water was added to increase the volume to 100 μl. Each mixture was heated to 94°C for 5 min, and PCR was then performed under the following conditions: 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s. Thermal cycling was terminated by polymerization at 72°C for 10 min. Two percent agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to examine the quality of the PCR products. These products were then stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV irradiation.

ITS1 DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Both strands of the PCR products were directly sequenced by using a DNA sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) with primers 18SF1 and 58SR1 and an automatic sequencer (ABI Genetic Analyzer 310; Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ITS1 sequences were aligned by using the Clustal W computer program (12), and the base positions with gaps were excluded. The phylogenetic tree was then constructed by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (19), using the NJPLOT program (10). Bootstrap analysis (9) was performed with Clustal W, using 1,000 random samples from the multiple alignment. This provided a measure of how well supported parts of the tree are, given the data set and the method used to construct the tree. The tree was rooted with T. rubrum as an outgroup.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

ITS1-homologous and -identical groups of T. mentagrophytes complex and T. rubrum, based on this study

| ITS1-homologous group | ITS1-identical group

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Straina | Accession no. | |

| rubrumI | A. vanbreuseghemii | VUT77007 | AB011466 |

| A. vanbreuseghemii | VUT77008 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (human isolate) | TIMM1187 | AB011463 | |

| T. mentagrophytes (human isolate) | TIMM3246 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (human isolate) | TIMM3258 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (human isolate) | TIMM3282 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (human isolate) | TIMM3295 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 1) | TLD0015 | AB011465 | |

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 2) | TLD0014 | AB011462 | |

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 3) | TLD0017 | AB011464 | |

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 3) | TLD0019 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 3) | TLD0020 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 3) | TLD0021 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 3) | TLD0027 | ||

| II | A. simii (type 1) | VUT77010 | AB011461 |

| A. simii (type 2) | SM160 | AB011460 | |

| A. simii (type 2) | VUT77009 | ||

| A. simii (type 3) | CBS520.75 | AB011459 | |

| A. simii (type 4) | SM161 | AB011458 | |

| III | A. benhamiae (Americano-European race) | SM103 | AB011457 |

| A. benhamiae (Americano-European race) | SM104 | ||

| A. benhamiae (African race) | SM165 | AB011454 | |

| A. benhamiae (African race) | SM166 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei | SM162 | AB011455 | |

| T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei | SM163 | ||

| T. mentagrophytes (animal type 4) | TLD0329 | AB011456 | |

| T. rubrum | T. rubrum | TIMM3223 | AB011453 |

| T. rubrum | TIMM3224 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3231 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3232 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3276 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3286 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3288 | ||

| T. rubrum | TIMM3620 | ||

| T. rubrum | TLD0070 | ||

| T. rubrum | TLD0078 | ||

| T. rubrum | TLD0080 | ||

CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands; IMI, International Mycological Institute, Surrey, United Kingdom; RV, Institute de Medicine Tropicale, Antwerp, Belgium; SM, Department of Dermatology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan; TIMM, Teikyo University Institute of Medical Mycology, Tokyo, Japan; TLD, Laboratory of Dermatology, School of Medical Science, Teikyo University; VUT, Department of Veterinary Internal Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

RESULTS

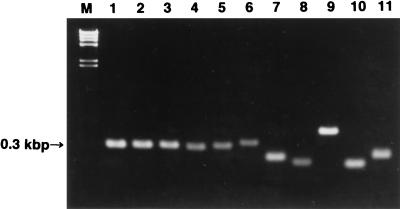

An ethidium bromide-stained gel image of PCR products prepared from various fungi by using the primer pair 18SF1 and 58SR1 is shown in Fig. 1. Clear single bands are seen in each sample lane. The size of specific bands among members of the T. mentagrophytes complex, however, was always 0.3 kbp, while those from other species of fungi differed from each other.

FIG. 1.

Gel image of PCR products prepared with primer pair 18SF1 and 58SR1 from DNA of various species of fungi. To determine the DNA sequence of the ITS1 region, a specific primer pair, 18SF1 and 58SR1, was used to amplify by PCR a DNA fragment from genomic DNA isolated from fungal cells. The PCR products were electrophoresed, and after being stained, the gel was visualized under UV irradiation. Lanes: M, HindIII-digested lambda phage DNA; 1, A. vanbreuseghemii VUT77008; 2, T. mentagrophytes human clinical isolate TIMM3295; 3, A. simii VUT77010; 4, A. benhamiae, Americano-European race, SM103; 5, T. rubrum TIMM3231; 6, Microsporum canis TIMM0765; 7, P. marneffei IFM41707; 8, C. albicans ATCC10231; 9, C. glabrata TIMM1062; 10, Trichosporon beigelii TIMM3140; 11, Mucor circinelloides TIMM1325.

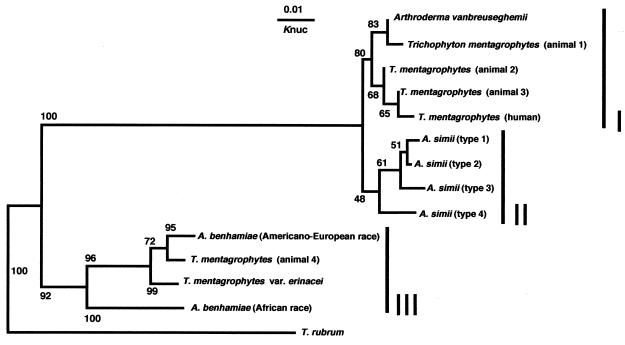

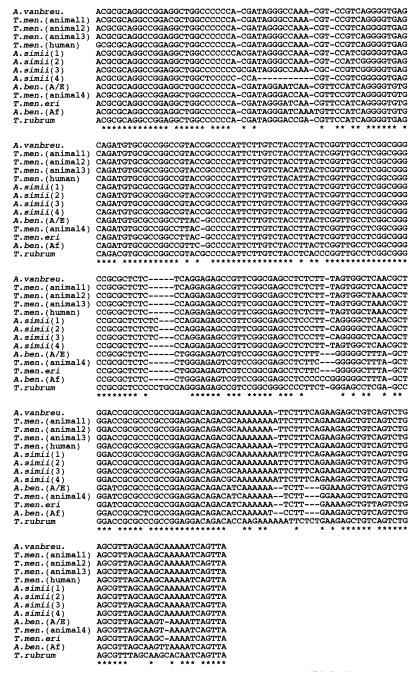

A phylogenetic tree, prepared by the NJ method, was constructed from 26 strains of T. mentagrophytes complex and 11 strains of T. rubrum (Fig. 2). Their ITS1 region sequences are shown in Fig. 3; the sizes of these regions ranged from 246 to 259 bp. The evolutionary distances between organisms are indicated by the horizontal branch lengths, which reflect the number of nucleotide substitutions per site along the branches from node to endpoint. The percentages of bootstrap samplings supporting the interior branches are noted. Members of the T. mentagrophytes complex were classified into three ITS1-homologous groups (I, II, and III) and 13 ITS1-identical individual groups by the DNA sequences of their ITS1 regions. ITS1-homologous groups I and II comprised a monophyletic cluster (100% bootstrap support), and ITS1-homologous group III comprised another cluster (92% bootstrap support). ITS1-homologous group I was 80% bootstrap supported, but for ITS1-homologous group II the support was 48%. ITS1-homologous group I is composed of A. vanbreuseghemii, T. mentagrophytes human isolates, and several strains of T. mentagrophytes animal isolates. Five strains of A. simii form a cluster in ITS1-homologous group II. Both of the A. benhamiae races, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei, and one strain of a T. mentagrophytes animal isolate are members of ITS1-homologous group III. The base sequences of the following strains were identical: both strains of A. vanbreuseghemii, 5 of 8 strains of T. mentagrophytes animal isolates (animal type 3), all 5 strains of T. mentagrophytes human isolates, A. simii SM160 and VUT77009, both strains of A. benhamiae Americano-European race, both strains of A. benhamiae African race, both strains of T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei, and all 11 strains of T. rubrum human and animal isolates. Each of the remaining strains (T. mentagrophytes animal type 1, TLD0015; T. mentagrophytes animal type 2, TLD0014; T. mentagrophytes animal type 4, TLD0329; A. simii type 1, VUT77010; A. simii type 3, CBS520.75; and A. simii type 4, SM161) was shown to have unique ITS1 base sequences (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

T. mentagrophytes complex and T. rubrum phylogenetic tree, based on ITS1 rDNA sequences. The NJ tree was constructed by using ITS1 sequence data for strains T. mentagrophytes complex and 11 T. rubrum (Table 1). The evolutionary distances between organisms are indicated by the horizontal branch lengths, which reflect the numbers of nucleotide substitutions per site along the branches from node to endpoint. The percentages of bootstrap samplings, derived from 1,000 samples which were supporting the interior branches, are noted. Members of the T. mentagrophytes complex were classified into 3 ITS1-homologous groups and 13 ITS1-identical groups (Table 2), and all strains of T. rubrum had identical ITS1 sequences. I, ITS1-homologous group I; II, ITS1-homologous group II; III, ITS1-homologous group III.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of ITS1 sequences of T. mentagrophytes complex and T. rubrum. The ITS1 rDNA sequences of 13 ITS1-identical individual groups of the T. mentagrophytes complex (Table 2) and of T. rubrum were aligned by using the Clustal W computer program (11). Hyphens designate gaps added to permit alignment; asterisks indicate conserved bases. A. vanbreu., A. vanbreuseghemii; T.men. (animal1) to T.men. (animal4), T. mentagrophytes animal type 1 to 4 isolates, respectively; T.men.(human), T. mentagrophytes human isolate; A.simii(1) to A.simii(4), A. simii type 1s to 4, respectively; A.ben.(A/E) and A.ben.(Af), A. benhamiae Americano-European and African races, respectively; T.men.eri, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei.

DISCUSSION

Using ITS1 rDNA sequences from 37 strains of fungi, we demonstrated the phylogeny of members of the T. mentagrophytes complex. The phylogenetic relationship based on the alignment of the ITS1 DNA sequences of perfect and imperfect states of the complex agreed with the proposed taxonomic connection in its sexual compatibility (22) and RFLP analysis of mtDNA (17). However, because of their highly variable ITS1 sequences, strains of A. simii and asexual strains of T. mentagrophytes could be distinguished from each other in more detail.

Earlier in this paper, we stated that there are three ITS1-homologous groups and 13 ITS1-identical individual groups in the complex. Clusters of ITS1-homologous group I (which includes A. vanbreuseghemii, animal isolates of T. mentagrophytes, and a human isolate of T. mentagrophytes) and of ITS1-homologous group III (which includes both races of A. benhamiae, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei, and an animal isolate of T. mentagrophytes) were supported by bootstrap analysis, although ITS1-homologous group II (which includes all five strains of A. simii) was not properly supported by a percentage of bootstrap sampling. The clustering of A. simii, however, was supported by another phenotypic character, concerning mating ability, and so it was proven to be a unique species. It is suggested that the speed of base substitution of ITS1 sequences in A. simii is high enough to construct a unique cluster, although the bootstrap value is apparently low. Because ITS1-homologous group I was supported as a monophyletic group, the human isolate of T. mentagrophytes, animal isolates of T. mentagrophytes, and A. vanbreuseghemii seemed to have diverged from the same origin.

According to the phylogenic tree shown in Fig. 2, in the complex, ITS1-homologous groups I and II are closely related but ITS1-homologous group III is related to groups I and II only distantly. This phylogenetic relationship was also revealed by Nishio and colleagues in their RFLP analysis of mtDNAs of Trichophyton spp. (18). T. mentagrophytes strains fall into six groups having different ITS1 sequences. Four of them, the T. mentagrophytes animal type 1 to 3 strains and the human T. mentagrophytes isolate, belong to ITS1-homologous group I, as does A. vanbreuseghemii, while two, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei and the T. mentagrophytes animal type 4 strain, belong to ITS1-homologous group III, as does A. benhamiae. The ITS1 sequences of all 11 strains of T. rubrum are identical, as are those of all 5 human isolates of T. mentagrophytes.

We demonstrated the applicability of ITS1 DNA sequences to phylogenetic analysis of closely related strains of the T. mentagrophytes complex. This ITS1-based system will prepare the way for the more complicated phylogenetic classification of dermatophytes and other fungi.

Using the information from these short (approximately 100 to 400 bp), specific, and wide-ranging ITS1 rDNA sequences (as shown in Fig. 1) would be beneficial not only for phylogenic study but also for species identification. It enables speedy (2 to 3 days) and accurate identification of pathogenic fungi to the species level. The classical method of species identification takes at least several weeks and then is sometimes unsuccessful. The method described in the present paper would allow medical doctors to determine the involved pathogen and to advise the patient of the proper way to control against infection by the fungus, epidemiologically or etiologically. For example, as we stated earlier, human and animal isolates of T. mentagrophytes were clearly distinguishable.

Further evaluation of the phylogenic analysis and identification systems, both of which are based on ITS1 rDNA sequences, is under way in our laboratory, with other species and strains being employed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Takashi Sugita, Department of Microbiology, Meiji College of Pharmacy, for technical advice and Yoshiko Tamura, Teikyo University Institute of Medical Mycology, for research assistance.

This study was partly supported by the Proposal-Based Advanced Industrial Technology R & D Program (no. B-276) of the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajello L, Cheng S-L. The perfect state of Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Sabouraudia. 1967;5:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berbee M L, Yoshimura A, Sugiyama J, Taylor J W. Is Penicillium monophyletic? An evaluation of phylogeny in the family Trichocomaceae from 18S, 5.8S and ITS ribosomal DNA sequence data. Mycologia. 1995;87:210–222. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbone I, Kohn L M. Ribosomal DNA sequence divergence within internal transcribed spacer 1 of the Sclerotiniaceae. Mycologia. 1993;85:415–427. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cenis J L. Rapid extraction of fungal DNA for PCR amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2380. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.9.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson F D, Mackenzie D W R, Owen R J. Deoxyribonucleic acid base compositions of dermatophytes. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;118:465–470. doi: 10.1099/00221287-118-2-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson F D, Mackenzie D W R. DNA homology studies in the taxonomy of dermatophytes. J Med Vet Mycol. 1984;2:117–123. doi: 10.1080/00362178485380191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bièvre C, Dauguet C, Nguyen V H, Iburahim-Granet O. Polymorphism in mitochondria DNA of several Trichophyton rubrum isolates from clinical specimens. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1987;138:719–727. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emmons C W. Dermatophytes. Natural grouping based on the form of the spores and accessory organs. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1934;30:337–362. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouy M. NJPLOT. Lyon, France: University of Lyon 1; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmsen D, Schwinn A, Weig M, Bröcker E-B, Heesemann J. Phylogeny and dating of some pathogenic keratinophilic fungi using small subunit ribosomal RNA. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;33:299–303. doi: 10.1080/02681219580000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins D. Clustal W, version 1.6. Cambridge, United Kingdom: The European Bioinformatics Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki M, Aoki M, Ishizaki H, Nishio K, Mochizuki T, Watanabe S. Phylogenetic relationships of the genera Arthroderma and Nanizzia referred from mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mycopathologia. 1992;118:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00442537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leclerc M C, Philippe H, Guého E. Phylogeny of dermatophytes and dimorphic fungi based on large subunit ribosomal RNA sequence comparisons. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:331–341. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobuglio K, Pitt J I, Taylor J W. Phylogenetic analysis of two ribosomal DNA regions indicates multiple independent losses of a sexual Talaromyces state among asexual Penicillium species in subgenus Biverticillium. Mycologia. 1993;85:592–604. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makimura K, Murayama S Y, Yamaguchi H. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungi by the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:358–364. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-5-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mochizuki T, Takada K, Watanabe S, Kawasaki W, Ishizaki H. Taxonomy of Trichophyton interdigitale (Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitale) by restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:191–196. doi: 10.1080/02681219080000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishio K, Kawasaki M, Ishizaki H. Phylogeny of the genera Trichophyton using mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mycopathologia. 1992;117:127–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00442772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockdale P M, Mackenzie D W R, Austwick P K C. Arthroderma simii sp. nov., the perfect state of Trichophyton simii (Pinoy) comb. nov. Sabouraudia. 1965;4:112–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takashio M. Observations on African and European strains of Arthroderma benhamiae. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974.tb01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takashio M. The Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex. In: Iwata K, editor. Recent advances in medical and veterinary mycology. Tokyo, Japan: University of Tokyo Press; 1977. pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weitzman I, Summerbell R C. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:240–259. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]