Abstract

Background:

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), an inhibitor of fibrinolysis that is associated with adiposity, has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. However, whether circulating PAI-1 levels are altered during preclinical AD remains unclear.

Objective:

To measure plasma PAI-1 levels in cognitively normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarker positive and biomarker negative participants and to examine the association of plasma PAI-1 levels with CSF AD biomarkers and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, plasma PAI-1 levels were measured in 155 cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating, CDR 0) non-obese older adults. 29 men and 26 women were classified as preclinical AD by previously established CSF tau/Aβ42 criteria. All analyses were sex stratified due to reported sex differences in PAI-1 expression.

Results:

Plasma PAI-1 levels were associated with body mass index (BMI) but not age in men and women. In men, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were lower in preclinical AD compared to control. Plasma PAI-1 levels were positively associated with CSF amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 and negatively associated with CSF tau/Aβ42, while BMI was positively associated with CSF Aβ42 and negatively associated with CSF p-tau181 and CSF tau/Aβ42. In women, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were similar between preclinical AD and control and were not associated with CSF AD biomarkers. For men and women, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were not associated with MMSE scores.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that there are significant sex differences in the systemic metabolic changes seen in the preclinical stage of AD.

Keywords: Adipokines, Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid beta-peptides, body weight, body mass index, biomarker, immunoassay, PAI-1, sexual dimorphism, tau proteins

INTRODUCTION

The ability to identify the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), in which amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins pathologically accumulate over a period of years to decades before the onset of cognitive decline, using positron emission topography (PET) imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers offers a window of opportunity to investigate the early pathobiology of AD [1, 2]. Accumulating evidence suggests that deficits in systemic metabolism such as weight loss may be an important non-cognitive manifestation of preclinical AD that can contribute to AD pathogenesis [3, 4]. Since systemic metabolic dysfunction is often reflected and caused by alterations in the levels of circulating adipocyte hormones or adipokines, circulating adipokines could serve as peripheral biofluid markers or therapeutic targets early in the pathogenesis of AD [4, 5].

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), a serine protease, is a primary inhibitor of fibrinolysis by acting as the endogenous inhibitor for tissue-type plasminogen activator [6]. In the periphery, PAI-1 is expressed in a wide variety of tissues and cell types including platelets, liver, endothelial cells, and macrophages [6]. PAI-1 is also secreted by adipose tissue as an adipokine with circulating PAI-1 levels significantly associated with adiposity, body mass index (BMI), peripheral insulin resistance, and diabetes [7–9]. Therefore, PAI-1 is well-positioned to serve as an important link between vascular disease and systemic metabolism, both of which can significantly contribute to AD pathogenesis [10]. However, studies investigating circulating levels of PAI-1 in AD have been conflicting with published reports of both increased and decreased levels of circulating PAI-1 during the various clinical stages of AD [11–17]. Furthermore, there have been no studies to date investigating circulating PAI-1 levels during preclinical AD, as classified by CSF AD biomarkers. Our present study sought to clarify the role of circulating PAI-1 in preclinical AD by determining if plasma PAI-1 levels are altered in the preclinical stage of AD and examining the associations of plasma PAI-1 levels with AD pathology and global cognitive function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

All participants were research volunteers enrolled in cohort studies at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis [18–20]. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) community-dwelling adults age 50 years or older (mean 68.7, range 51.1 to 86.3); 2) normal cognitive function as defined by Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] of 0 [21]; 3) no other known medical illness that could contribute to dementia; 4) and fasting biospecimen samples of suitable quality for analyses [19, 20]. Study exclusion criteria was BMI greater than or equal to 30 to exclude obesity as a possible confounder [4, 19, 20].

CSF levels of Aβ42, Aβ40, total tau, and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau181) were measured by chemiluminescent enzyme linked immunoassay using a fully automated platform (LUMIPULSE G1200, Fujirebio) as previously described [22]. Positive AD pathology was defined using the previously established cutoff of CSF tau/Aβ42 level > 0.54 [22]. Genotypes of Apolipoprotein E (APOE) were obtained as described [18]. Global cognitive function was tested using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [23]. Preclinical AD was defined as cognitively normal (CDR 0) study participants with positive CSF AD pathology, while control was defined as cognitively normal (CDR 0) study participants with negative CSF AD pathology [1].

This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the Institutional Review Board at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and their informants.

Plasma samples and immunoassay measurement of PAI-1

Fasting plasma samples stored in aliquots at −80°C were sent de-identified to Weill Cornell Medicine for analysis. Total levels of PAI-1 were measured in the plasma using the MAGPIX system (Luminex Corporation) and a commercially available immunoassay (Catalog Number HADK1MAG-61K; Millipore Sigma) following the manufacturers’ protocols [19]. Diluted (1 : 400) plasma samples were run in duplicates. All values used are the mean values of the duplicates with the mean %CV of replicates 5.0%. No sample values used in this study were found outside of the standard curve.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using a commercial software (Stata version 13.1, StataCorp, TX). Plasma PAI-1 levels were natural logarithmic transformed to normalize the data. Variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation). For comparisons between groups with continuous measures, t-test was used. For comparisons between groups with categorical measures, Fisher’s exact test was used. Spearman’s correlations were used to examine associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI or age in years. Associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and the individual CSF AD biomarkers as continuous measures were examined by linear regression and adjusted for age, APOE genotype (E4 to non-E4 carriers), and BMI, as there were significant differences in these variables between preclinical AD and control groups, while associations between BMI and the individual CSF AD biomarkers as continuous measures were adjusted for age and APOE genotype (E4 to non-E4 carriers). Associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and MMSE scores as continuous measures were examined by linear regression and adjusted for the age, BMI, and years of education, while associations between BMI and MMSE scores as continuous measures were adjusted for the age and years of education. All tests were two-tailed. p < 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Demographics of study participants

155 study participants (64 men and 91 women) met all study criteria. Using a previously defined CSF tau/Aβ42 criterion for preclinical AD [22], 55 study participants (29 men and 26 women) were categorized as preclinical AD, and 100 study participants (35 men and 65 women) were categorized as CSF biomarker-negative controls. Due to reported differences in the biology of PAI-1 between men and women [24], all data were sex stratified and analyzed separately for men and women. Compared to control study participants, both men and women with preclinical AD had significantly lower CSF Aβ42 levels, higher CSF tau levels, higher CSF p-tau181 levels, lower CSF Aβ42/Aβ40, and higher CSF tau/Aβ42 (Table 1). Additionally, women with preclinical AD had higher CSF Aβ40 levels than control study participants (Table 1). As expected, for both men and women, preclinical AD study participants were older with an increased percentage of carriers for the APOE E4 allele as compared to the control study participants (Table 1). In men but not women, BMI was significantly lower in preclinical AD study participants compared to control study participants (Table 1). Race and years of education were similar between preclinical AD and control study participants in both men and women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study demographics and characteristics

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Preclinical AD | P | Control | Preclinical AD | p | |

| (N=35) | (N=29) | (N=65) | (N=26) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 68.2 (6.7) | 76.1 (5.7) | *** | 64.6 (8.1) | 71.3 (5.1) | *** |

| Caucasian, number (%) | 34 (97.1) | 29 (100) | >0.99 | 63 (96.9) | 26 (100) | >0.99 |

| CSF Aβ42, mean (SD), pg/mL | 886.5 (274.5) | 482.0 (154.5) | *** | 928.0 (355.8) | 586.3 (208.6) | *** |

| CSF Aβ40, mean (SD), pg/mL | 10,946.8 (3077.3) | 11,188.2 (2738.3) | 0.74 | 10,652.3 (3294.2) | 12,611.7 (4096.1) | 0.036 |

| CSF tau, mean (SD), pg/mL | 267.7 (76.3) | 560.4 (224.2) | *** | 248.9 (97.5) | 534.8 (223.4) | *** |

| CSF p-tau181, mean (SD), pg/mL | 35.6 (9.2) | 75.8 (31.0) | *** | 32.2 (10.0) | 70.5 (32.6) | *** |

| CSF Aβ42/A040, mean (SD) | 0.081 (0.013) | 0.044 (0.014) | *** | 0.086 (0.013) | 0.047 (0.012) | *** |

| CSF tau/Aβ42, mean (SD) | 0.31 (0.07) | 1.23 (0.55) | *** | 0.28 (0.08) | 0.96 (0.38) | *** |

| APOE E4 isoform carrier, number (%) | 10 (28.6) | 17 (58.6) | 0.02 | 14 (21.5) | 13 (50.0) | 0.01 |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 16.5 (2.6) | 16.1 (2.5) | 0.55 | 15.9 (2.5) | 15.3 (2.7) | 0.39 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.4 (1.7) | 25.0 (2.1) | 0.005 | 24.0 (3.0) | 23.5 (3.4) | 0.49 |

p < 0.001; SD, standard deviation.

Plasma PAI-1 levels are associated with BMI but not age in older non-obese men and women

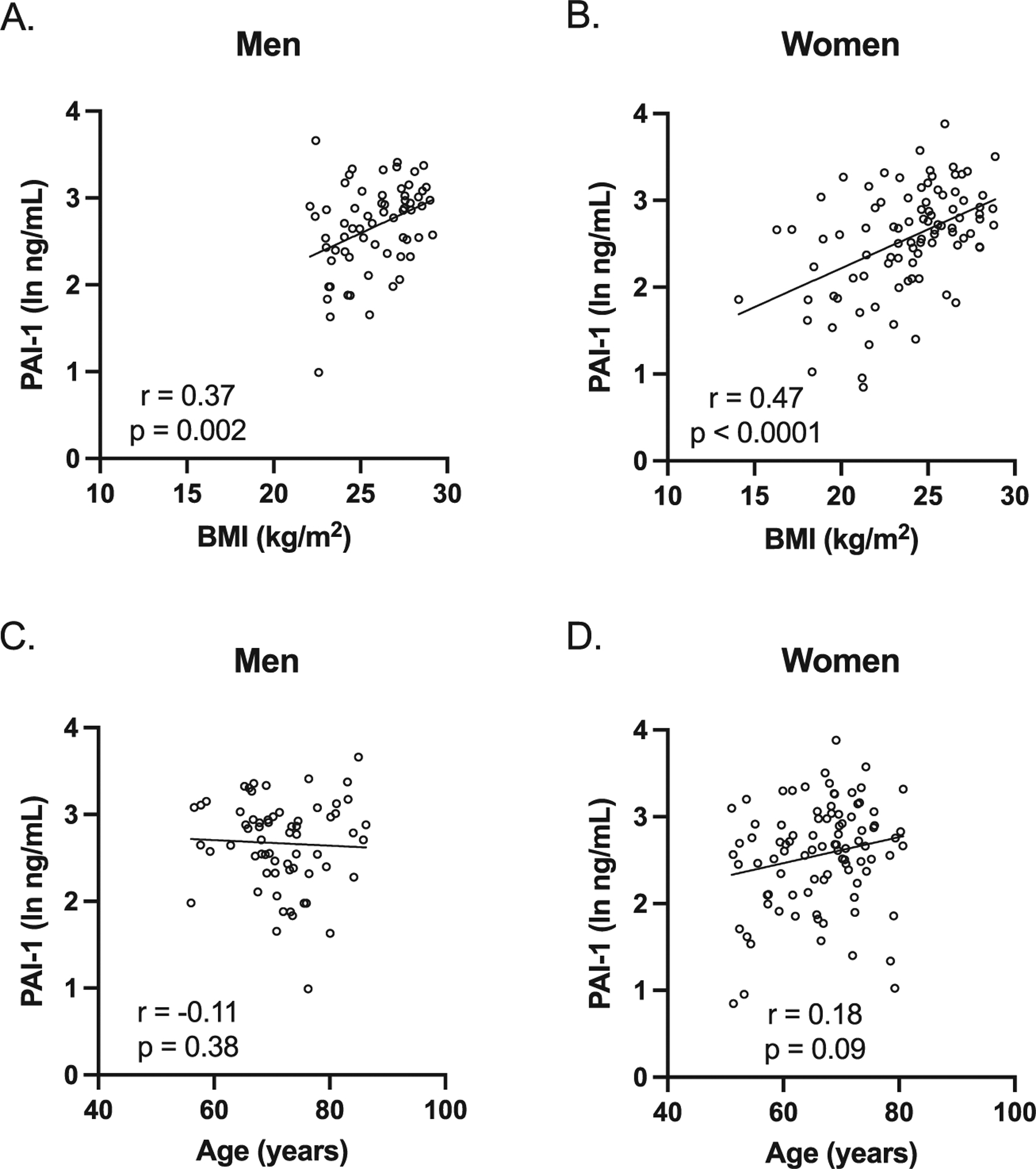

As circulating PAI-1 levels have been reported to be associated with increasing adiposity, BMI, and age [7, 24], these relations were examined in our cohort. Plasma PAI-1 levels were significantly associated with BMI in both men and women (Fig. 1A, B). However, plasma PAI-1 levels were not associated with age in both men and women (Fig. 1C, D), although these analyses are not conclusive given the restricted age range to older adults in our study.

Fig. 1.

Plasma PAI-1 levels were associated with BMI but not with age in both men and women. A, B) PAI-1 levels were positively associated with BMI in both men and women (men: Spearman r = 0.37, p = 0.002; women; Spearman r = 0.47, p < 0.0001). C, D) PAI-1 levels were not associated with age in both men and women (men: Spearman r = −0.11, p = 0.38; women; Spearman r = 0.18, p = 0.09). Individual values with unadjusted regression lines are shown in the scatterplots.

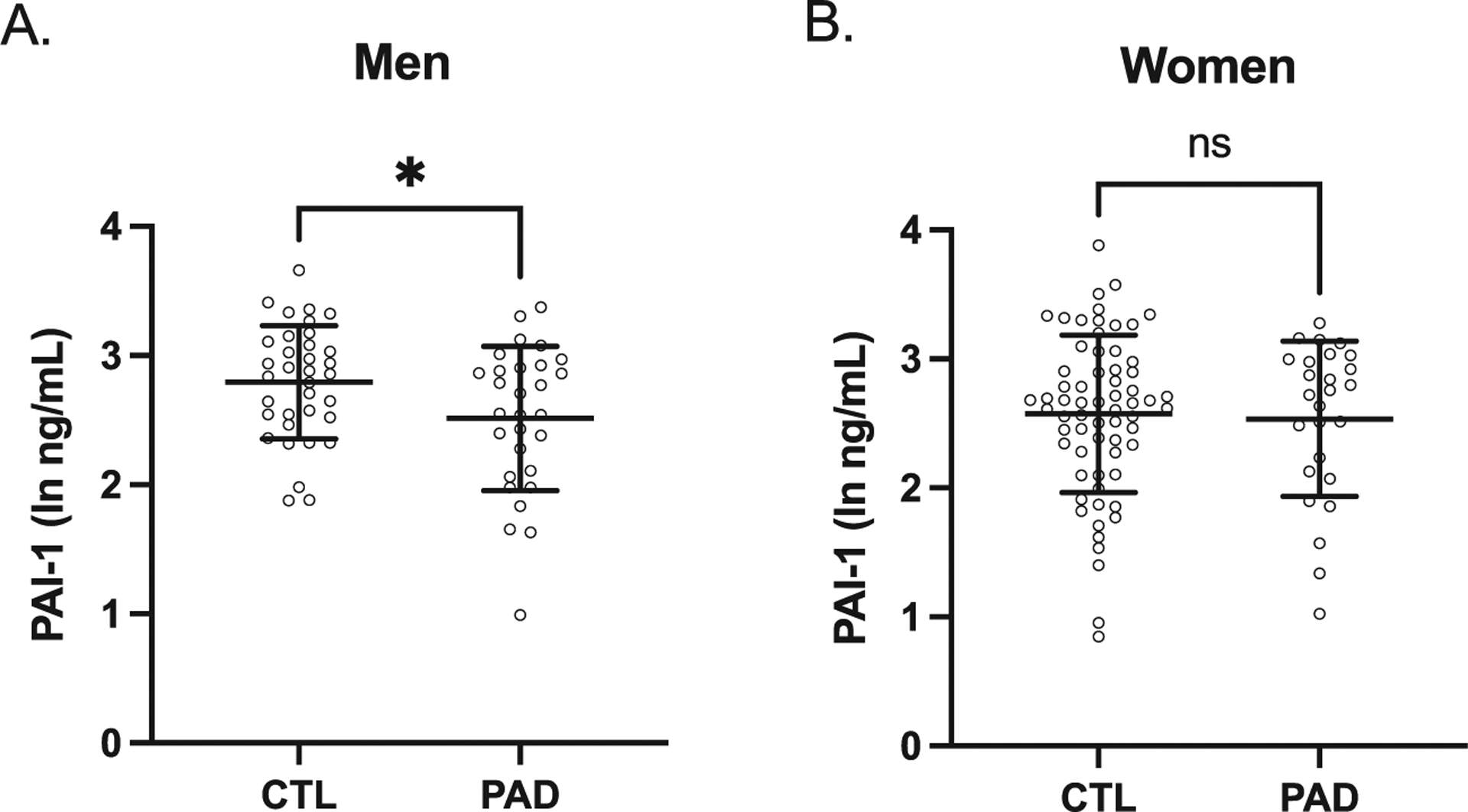

Plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI are lower in preclinical AD and associated with AD pathology in men but not women

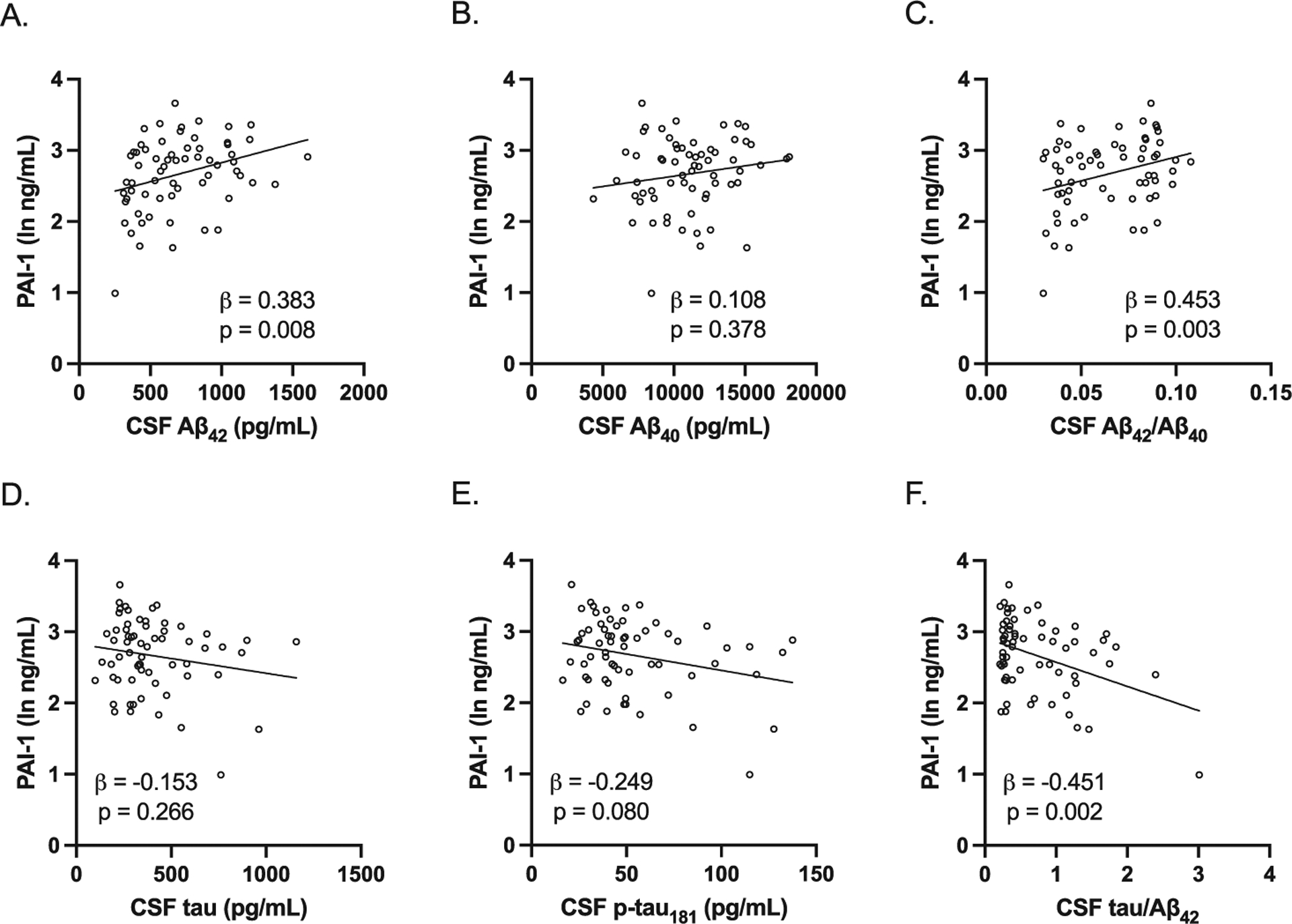

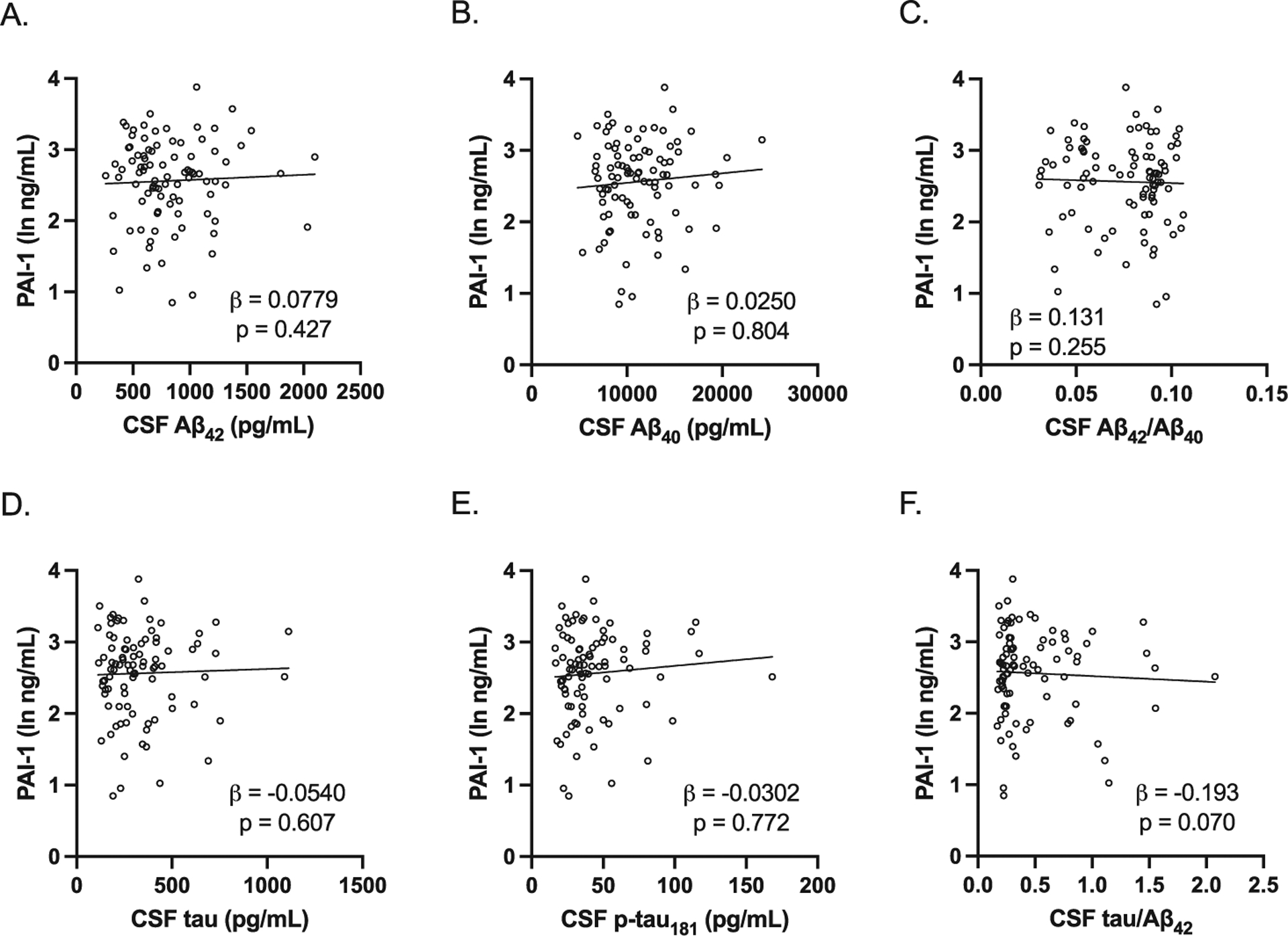

We next determined if there were any differences in plasma PAI-1 levels between preclinical AD and control study participants. In men, plasma PAI-1 levels were significantly lower in preclinical AD compared to control study participants (Fig. 2A); however, in women, there was no difference in plasma PAI-1 levels between preclinical AD and control study participants (Fig. 2B). We then examined the associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and CSF AD biomarkers adjusting for age, BMI, and APOE E4 carrier status, as these were found to be significantly different between preclinical AD and control study participants. In men, plasma PAI-1 levels were positively associated with CSF Aβ42 levels and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 and negatively associated with CSF tau/Aβ42 (Fig. 3). However, in women, plasma PAI-1 levels were not significantly associated with any of the CSF AD biomarkers (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained when plasma PAI-1 levels were combined for men and women and sex used as an additional covariate (Supplementary Figure 1).

Fig. 2.

Plasma PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD group were lower than the CSF biomarker-negative control group in men but not women. A) In men, plasma PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD group were significantly lower than the control group (ln-PAI1 ng/mL: control 2.79±0.44, preclinical AD 2.52±0.56, p = 0.03, n = 35 control and 29 preclinical AD study participants). B) In women, plasma PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD group were similar to the control group (ln-PAI1 ng/mL: control 2.57±0.61, preclinical AD 2.54±0.60, p = 0.79, n = 65 control and 29 preclinical AD study participants). Individual values are shown with bars depicting means and standard deviations. CTL, control study participants; PAD, preclinical AD study participants; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Fig. 3.

Association between plasma PAI-1 levels and CSF AD biomarkers in men. All study participants were included in the analysis. All were adjusted for age, BMI, and APOE E4 carrier status. A–C) Plasma PAI-1 levels were positively associated with CSF Aβ42 levels (adjusted beta coefficient 0.383, p = 0.008) and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 (adjusted beta coefficient 0.453, p = 0.003) but not CSF Aβ40 levels (adjusted beta coefficient 0.108, p = 0.378). D–F) Plasma PAI-1 levels were negatively associated with CSF tau/Aβ42 (adjusted beta coefficient −0.451, p = 0.002) but not CSF tau levels (adjusted beta coefficient −0.153, p = 0.266) and CSF p-tau181 levels (adjusted beta coefficient −0.249, p = 0.080). Individual values with unadjusted regression lines are shown in the scatterplots.

Fig. 4.

Association between plasma PAI-1 levels and CSF AD biomarkers in women. All study participants were included in the analysis. All were adjusted for age, BMI, and APOE E4 carrier status. There were no significant associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and the CSF AD biomarkers (A, CSF Aβ42 adjusted beta coefficient 0.0779, p = 0.427; B, CSF Aβ40 levels adjusted beta coefficient 0.0250, p = 0.804; C, CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 adjusted beta coefficient 0.131, p = 0.255; D, CSF tau adjusted beta coefficient −0.0540, p = 0.607; E, CSF p-tau181 adjusted beta coefficient −0.0302, p = 0.772; F, CSF tau/Aβ42 adjusted beta coefficient −0.193, p = 0.070). Individual values with unadjusted regression lines are shown in the scatterplots.

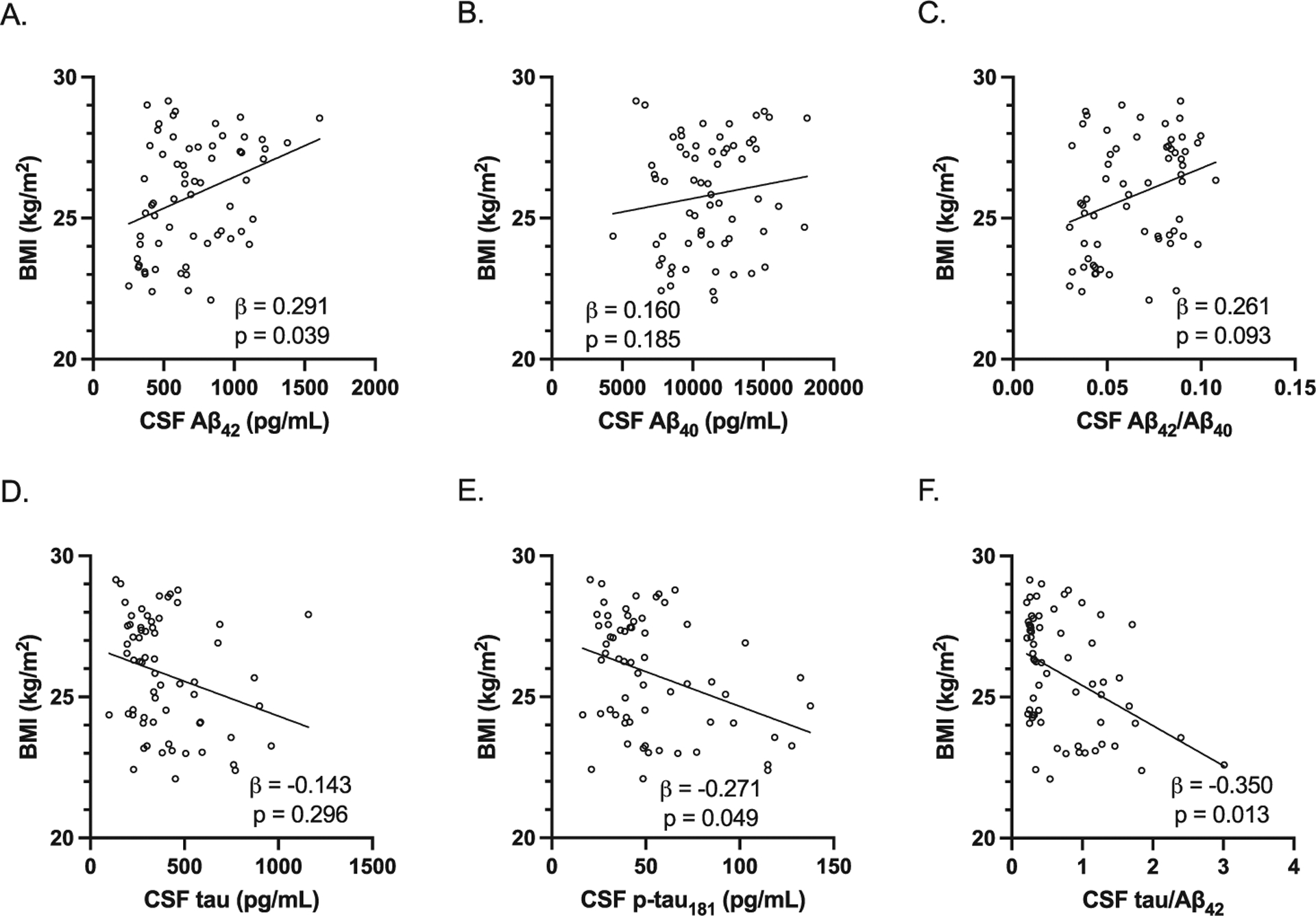

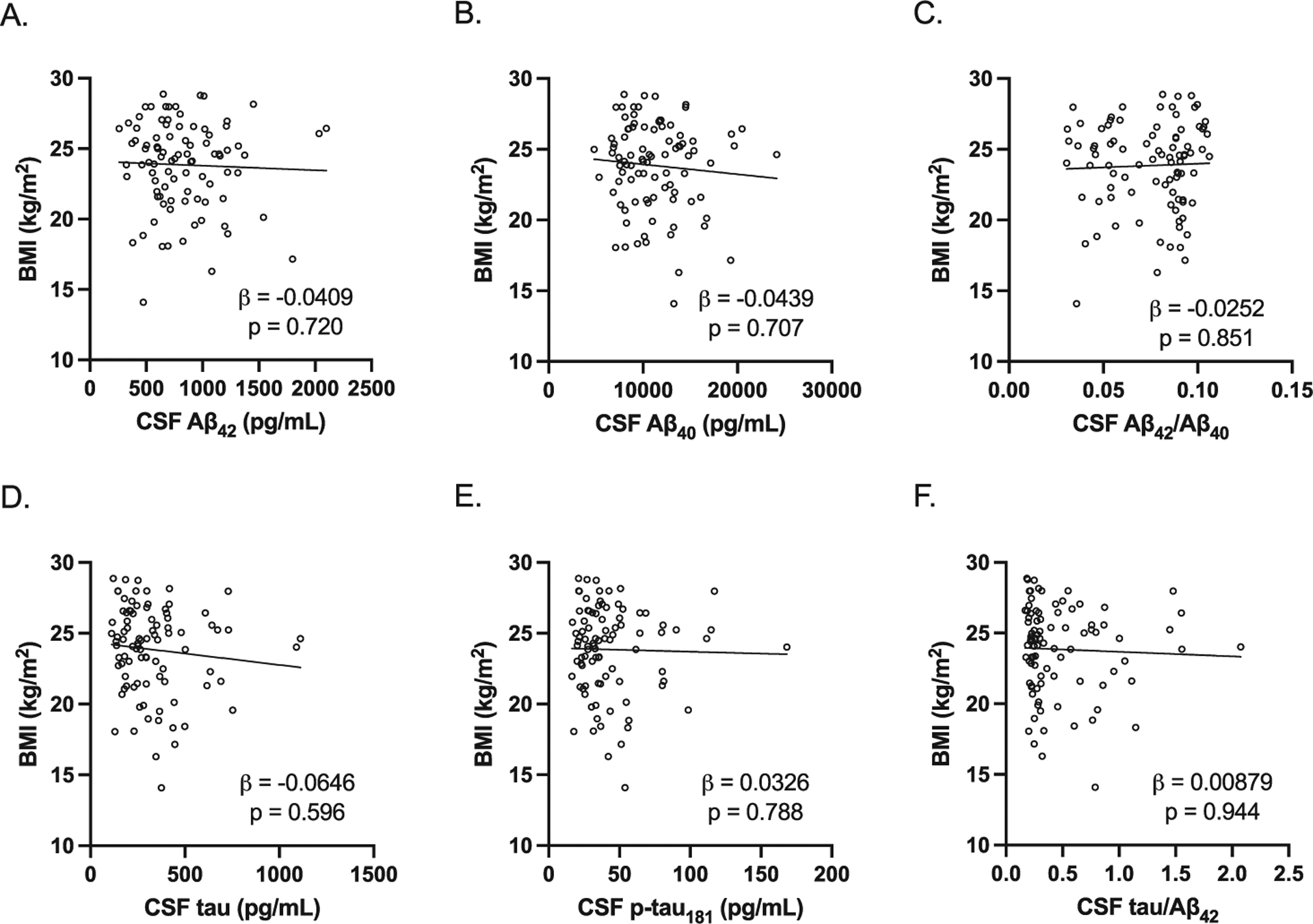

As BMI was significantly lower in preclinical AD compared to control study participants in men, we also examined the association between BMI and CSF AD biomarkers adjusting for age and APOE E4 carrier status. In men, BMI was positively associated with CSF Aβ42 levels and negatively associated with CSF p-tau181 levels and CSF tau/Aβ42 (Fig. 5). However, in women, BMI was not significantly associated with any of the CSF AD biomarkers (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Association between BMI and CSF AD biomarkers in men. All study participants were included in the analysis. All were adjusted for age and APOE E4 carrier status. A–C) BMI was positively associated with CSF Aβ42 levels (adjusted beta coefficient 0.291, p = 0.039) but not CSF Aβ40 levels (adjusted beta coefficient 0.160, p = 0.185) and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 (adjusted beta coefficient 0.261, p = 0.093). D–F) BMI was negatively associated with CSF p-tau181 levels (adjusted beta coefficient −0.271, p = 0.049) and CSF tau/Aβ42 (adjusted beta coefficient −0.350, p = 0.013) but not CSF tau levels (adjusted beta coefficient −0.143, p = 0.296). Individual values with unadjusted regression lines are shown in the scatterplots.

Fig. 6.

Association between BMI and CSF AD biomarkers in women. All study participants were included in the analysis. All were adjusted for age and APOE E4 carrier status. There were no significant associations between BMI and CSF AD biomarkers (A, CSF Aβ42 adjusted beta coefficient −0.0409, p = 0.720; B, CSF Aβ40 levels adjusted beta coefficient −0.0439, p = 0.707; C, CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 adjusted beta coefficient −0.0252, p = 0.851; D, CSF tau adjusted beta coefficient −0.0646, p = 0.596; E, CSF p-tau181 adjusted beta coefficient 0.0326, p = 0.788; F, CSF tau/Aβ42 adjusted beta coefficient 0.00879, p = 0.944). Individual values with unadjusted regression lines are shown in the scatterplots.

Plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI are not associated with MMSE scores

There have been conflicting reports regarding the association of circulating PAI-1 levels and cognitive function with studies showing both positive and negative associations with MMSE scores [12, 16]. Therefore, we examined whether plasma PAI-1 levels were associated with MMSE scores in our cohort. In both men and women, as expected, MMSE scores were within normal range with no significant difference between preclinical AD and control study participants (men: control 29.1±1.3, preclinical AD 28.5±1.4, p = 0.093; women: control 29.5±0.9, preclinical AD 29.3±0.9, p = 0.35). In both men and women, there were no significant associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and MMSE scores (men: adjusted beta coefficient −0.155, p = 0.184; B, women: adjusted beta coefficient 0.068, p = 0.586). Similarly, in both men and women, BMI was not associated with MMSE scores (men: adjusted beta coefficient −0.223, p = 0.053; women: adjusted beta coefficient −0.0334, p = 0.754).

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study of cognitively normal older adults, we found significant differences in plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI between preclinical AD and CSF biomarker-negative control study participants in a sexually dimorphic manner. In men, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were significantly lower in preclinical AD compared to control study participants, while in women, there was no difference in plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI between preclinical AD and control study participants. Furthermore, in men, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were significantly associated with several key CSF AD biomarkers. However, in women, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were not significantly associated with CSF AD biomarkers. For both men and women, cognitive function as measured by MMSE was not associated with plasma PAI-1 levels or BMI. These findings support a role for circulating PAI-1 early in the pathogenesis of AD and may reflect early systemic metabolic changes in men but not women with preclinical AD.

The lower plasma PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD are consistent with prior studies finding lower circulating PAI-1 levels in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia cohorts [11–15]. However, some studies have reported higher circulating levels in MCI and AD dementia cohorts [16, 17]. The conflicting results from the various studies could be due to relatively small number of study participants, demographic difference in study cohorts, and differences in sample collection that could influence circulating PAI-1 levels (e.g., nutritional status or time of day when samples were collected) [6, 25]. Of note, most studies reporting PAI-1 levels did not use AD biomarkers to classify individuals. Therefore, it is possible that there was misclassification in these studies and included individuals with MCI and dementia due to non-AD etiologies. It may be particularly important to distinguish cognitive impairment primarily due to AD pathology from those with significant contributions from vascular pathology, as increased PAI-1 levels can result in a thrombotic state promoting cardiovascular and cerebrovascular injury that could contribute to vascular cognitive impairment [6].

Two prior studies have examined plasma PAI-1 levels in CSF or PET AD biomarker defined cohorts [11, 12]. In 41 participants from the FINGER PET substudy, plasma PAI-1 levels were lower in PiB-PET amyloid positive compared to amyloid negative study participants [11]. In a larger cohort of 972 participants from the EMIF-AD MBD study with biofluid and imaging biomarkers to classify individuals as positive for amyloid pathology (A), tau pathology (T), and or neurodegeneration (N) using the ATN framework [2], plasma PAI-1 levels were significantly lower in those with AD pathology (A + TN+) and amyloid pathology (A + TN-) compared to those with no pathology (A-TN-) [12]. Furthermore, when this cohort was classified by clinical diagnosis, plasma PAI-1 levels were lower in MCI and AD study participants compared to cognitively normal study participants. Therefore, our results finding lower plasma PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD would be consistent with these two studies that used established AD biomarkers. Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to report plasma PAI-1 levels in CSF biomarker defined preclinical stage of AD and the association of plasma PAI-1 levels to CSF AD biomarkers in cognitively normal older adults, as the EMIF-AD MBD study cohort did not examine the preclinical stage of AD [12].

While our study focused on circulating or peripheral PAI-1, the changes in circulating levels of PAI-1 may not necessarily reflect what is happening in the brain, as PAI-1 can be produced centrally by astrocytes and other brain cells [6, 26]. Postmortem studies of AD brains have reported increased PAI-1 mRNA and protein levels in brain regions containing plaques and tangles [27–29]. Therefore, in the AD brain, increased PAI-1 levels may play a pathological role by inhibiting plasminogen activation and decreasing the formation of the protease plasmin, which can degrade aggregated Aβ, resulting in further accumulation of Aβ [29, 30]. Conversely, in the periphery, lower circulating PAI-1 levels may reflect a different physiological process, as PAI-1 is produced by several peripheral cell types including platelets, adipocytes, hepatocytes, and macrophages [6]. Since circulating PAI-1 levels are significantly associated with BMI (Fig. 1) and adiposity [7], the lower circulating PAI-1 levels may reflect, at least in part, a negative energy balance as seen by the low BMI in the men with preclinical AD (Table 1), which is consistent with the weight loss and lower BMI reported in the preclinical or prodromal stages of AD [31–34].

An interesting finding from our study was the sexual dimorphism in circulating PAI-1 levels, where men, but not women, with preclinical AD had significantly lower PAI-1 levels compared to controls. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no prior studies in AD that examined circulating PAI-1 levels stratified by sex. While there is evidence for sex differences contributing to differential PAI-1 expression [24], a possible reason for the sex difference in circuating PAI-1 levels in preclinical AD could be due to increased susceptibility of men with preclinical AD to systemic metabolic changes. Recent studies support this possibility. A population-based prospective study from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging found that the loss of body weight was greater in men who developed incident MCI compared to those that did not, but changes in body weight were similar for women who developed incident MCI and those that did not [35]. In another study examining the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort, individuals with lower BMI and higher polygenic risk factor were more likely to convert from MCI to AD compared to those with higher BMI; however, this relationship was significant only in men [36]. Our findings would be consistent with men being more susceptible to systemic metabolic changes including in adipokines such as PAI-1 during the preclinical or prodromal stages of AD. An increased susceptibility to systemic metabolic changes in men during the early preclinical or prodromal stages of AD could also explain why the association between CSF AD biomarkers and plasma PAI-1 and BMI were seen in men but not in women in our study of preclinical AD. However, why women might be protected from systemic metabolic changes during the early stages of AD is not clear. Nevertheless, other factors such as contributions from various hormonal states that can influence PAI-1 expression cannot be excluded [37]. Furthermore, it is not known if the sexual dimorphism seen in this study would persist in later stages of AD.

Whether circulating PAI-1 levels are associated with cognitive function remains controversial [12, 16]. In our study cohort, there was no significant association between plasma PAI-1 levels and MMSE. However, it will be difficult to discern any association in our study cohort, as all study participants had MMSE scores well within normal limits, and the MMSE is not a highly specific cognitive measure in high functioning individuals such as those in our study (all CDR 0).

A major strength of our study is the use of a well-characterized study cohort with established CSF AD biomarkers, which enabled for the investigation of plasma PAI-1 levels in CSF biomarker defined individuals with preclinical AD and the examination of the associations between plasma PAI-1 levels and established CSF AD biomarkers in cognitively normal older adults. Furthermore, by sex-stratifying, we have been able to identify potential sex differences during the preclinical stage of AD that may have been missed otherwise. A limitation of this study is that due to the cross-sectional nature we are unable to determine the temporal relationships between plasma PAI-1 levels and the CSF AD biomarkers. Moreover, as we did not measure CSF PAI-1 levels, it is not known if these changes in peripheral PAI-1 are associated with corresponding changes in the central nervous system during preclinical AD. Finally, selection bias is a possible concern as the study cohort is relatively small and racially homogenous from a single academic medical center.

In summary, in men, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were significantly lower in preclinical AD compared to CSF AD biomarker negative controls. Additionally, plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI were associated with key CSF AD biomarkers in men. Interestingly, in women, there was no difference in plasma PAI-1 levels and BMI between preclinical AD and control and no significant association with the CSF AD biomarkers. The exact mechanism for the sex difference is not clear. One possibility is that circulating PAI-1 levels may be reflecting early systemic metabolic changes as seen in the low BMI in men, but not women, with preclinical AD. Our study highlights the critical need to examine sex as a distinct biological variable, as important sex differences may be missed otherwise. Collectively, the results of our study suggest that alterations in circulating PAI-1 levels reflect systemic metabolic changes seen early in AD pathogenesis in a sexually dimorphic manner. Additional studies will be needed to verify and validate these results, to investigate the underlying mechanisms for any sex differences in AD, and to elucidate the clinical utility of PAI-1 as a blood biomarker of AD pathology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the volunteers from which these data were obtained. We would like to acknowledge Drs. Anne Fagan, Krista Moulder, David Holtzman, and Betsy Grant, the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50AG05681), Adult Children Study (P01AG026276), and Healthy Aging and Senile Dementia (P01AG03991) for providing the biospecimens and associated data used in this study.

This research study was supported by K08AG051179, R01AG070868, and UL1TR002384 from the National Institutes of Health and A2015485S and A2020363S from the BrightFocus Foundation. The sponsors did not have any role in the study design and conduct; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; and preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/22-0686r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-220686.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, Bakardjian H, Benali H, Bertram L, Blennow K, Broich K, Cavedo E, Crutch S, Dartigues JF, Duyckaerts C, Epelbaum S, Frisoni GB, Gauthier S, Genthon R, Gouw AA, Habert MO, Holtzman DM, Kivipelto M, Lista S, Molinuevo JL, O’Bryant SE, Rabinovici GD, Rowe C, Salloway S, Schneider LS, Sperling R, Teichmann M, Carrillo MC, Cummings J, Jack CR Jr., Proceedings of the Meeting of the International Working G, the American Alzheimer’s Association on “The Preclinical State of AD, July, Washington Dc USA (2016) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 12, 292–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors (2018) NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ishii M, Iadecola C (2015) Metabolic and non-cognitive manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease: The hypothalamus as both culprit and target of pathology. Cell Metab 22, 761–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ishii M, Iadecola C (2016) Adipocyte-derived factors in age-related dementia and their contribution to vascular and Alzheimer pathology. Biochim Biophys Acta 1862, 966–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kiliaan AJ, Arnoldussen IA, Gustafson DR (2014) Adipokines: A link between obesity and dementia? Lancet Neurol 13, 913–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tjarnlund-Wolf A, Brogren H, Lo EH, Wang X (2012) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases. Stroke 43, 2833–2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Kotani K, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Miura M, Fukuda Y, Takemura K, Tokunaga K, Matsuzawa Y (1996) Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: Possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat Med 2, 800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vague P, Juhan-Vague I, Aillaud MF, Badier C, Viard R, Alessi MC, Collen D (1986) Correlation between blood fibrinolytic activity, plasminogen activator inhibitor level, plasma insulin level, and relative body weight in normal and obese subjects. Metabolism 35, 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Alessi MC, Poggi M, Juhan-Vague I (2007) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol 18, 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Knopman DS, Amieva H, Petersen RC, Chetelat G, Holtzman DM, Hyman BT, Nixon RA, Jones DT (2021) Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pekkala T, Hall A, Mangialasche F, Kemppainen N, Mecocci P, Ngandu T, Rinne JO, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Kivipelto M, Solomon A (2020) Association of peripheral insulin resistance and other markers of type 2 diabetes mellitus with brain amyloid deposition in healthy individuals at risk of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 76, 1243–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shi L, Winchester LM, Westwood S, Baird AL, Anand SN, Buckley NJ, Hye A, Ashton NJ, Bos I, Vos SJB, Kate MT, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE, Vandenberghe R, Gabel S, Meersmans K, Engelborghs S, De Roeck EE, Sleegers K, Frisoni GB, Blin O, Richardson JC, Bordet R, Molinuevo JL, Rami L, Wallin A, Kettunen P, Tsolaki M, Verhey F, Lleo A, Sala I, Popp J, Peyratout G, Martinez-Lage P, Tainta M, Johannsen P, Freund-Levi Y, Frolich L, Dobricic V, Legido-Quigley C, Barkhof F, Andreasson U, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Streffer J, Lill CM, Bertram L, Visser PJ, Kolb HC, Narayan VA, Lovestone S, Nevado-Holgado AJ (2021) Replication study of plasma proteins relating to Alzheimer’s pathology. Alzheimers Dement 17, 1452–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yu S, Liu YP, Liu HL, Li J, Xiang Y, Liu YH, Jiao SS, Liu L, Wang Y, Fu W (2018) Serum protein-based profiles as novel biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 55, 3999–4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shen XN, Lu Y, Tan CTY, Liu LY, Yu JT, Feng L, Larbi A (2019) Identification of inflammatory and vascular markers associated with mild cognitive impairment. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 2403–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trollor JN, Smith E, Baune BT, Kochan NA, Campbell L, Samaras K, Crawford J, Brodaty H, Sachdev P (2010) Systemic inflammation is associated with MCI and its subtypes: The Sydney Memory and Aging Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 30, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oh J, Lee HJ, Song JH, Park SI, Kim H (2014) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 as an early potential diagnostic marker for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol 60, 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marksteiner J, Imarhiagbe D, Defrancesco M, Deisenhammer EA, Kemmler G, Humpel C (2014) Analysis of 27 vascular-related proteins reveals that NT-proBNP is a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A pilot-study. Exp Gerontol 50, 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vos SJ, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, Cairns NJ, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM (2013) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12, 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Eruysal E, Ravdin L, Kamel H, Iadecola C, Ishii M (2019) Plasma lipocalin-2 levels in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 11, 646–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ishii M, Kamel H, Iadecola C (2019) Retinol binding protein 4 levels are not altered in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and not associated with cognitive decline or incident dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 67, 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kaplow J, Vandijck M, Gray J, Kanekiyo M, Huyck E, Traynham CJ, Esquivel R, Fagan AM, Luthman J (2020) Concordance of Lumipulse cerebrospinal fluid t-tau/Abeta42 ratio with amyloid PET status. Alzheimers Dement 16, 144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Asselbergs FW, Williams SM, Hebert PR, Coffey CS, Hillege HL, Navis G, Vaughan DE, van Gilst WH, Moore JH (2006) The gender-specific role of polymorphisms from the fibrinolytic, renin-angiotensin, and bradykinin systems in determining plasma t-PA and PAI-1 levels. Thromb Haemost 96, 471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kluft C, Jie AF, Rijken DC, Verheijen JH (1988) Daytime fluctuations in blood of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) and its fast-acting inhibitor (PAI-1). Thromb Haemost 59, 329–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gravanis I, Tsirka SE (2005) Tissue plasminogen activator and glial function. Glia 49, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hino H, Akiyama H, Iseki E, Kato M, Kondo H, Ikeda K, Kosaka K (2001) Immunohistochemical localization of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in rat and human brain tissues. Neurosci Lett 297, 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Barker R, Kehoe PG, Love S (2012) Activators and inhibitors of the plasminogen system in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Mol Med 16, 865–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu RM, van Groen T, Katre A, Cao D, Kadisha I, Ballinger C, Wang L, Carroll SL, Li L (2011) Knockout of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces amyloid beta peptide burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 32, 1079–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tucker HM, Kihiko M, Caldwell JN, Wright S, Kawarabayashi T, Price D, Walker D, Scheff S, McGillis JP, Rydel RE, Estus S (2000) The plasmin system is induced by and degrades amyloid-beta aggregates. J Neurosci 20, 3937–3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Johnson DK, Wilkins CH, Morris JC (2006) Accelerated weight loss may precede diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 63, 1312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vidoni ED, Townley RA, Honea RA, Burns JM, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2011) Alzheimer disease biomarkers are associated with body mass index. Neurology 77, 1913–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hiller AJ, Ishii M (2018) Disorders of body weight, sleep and circadian rhythm as manifestations of hypothalamic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci 12, 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Muller S, Preische O, Sohrabi HR, Graber S, Jucker M, Dietzsch J, Ringman JM, Martins RN, McDade E, Schofield PR, Ghetti B, Rossor M, Graff-Radford NR, Levin J, Galasko D, Quaid KA, Salloway S, Xiong C, Benzinger T, Buckles V, Masters CL, Sperling R, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Laske C (2017) Decreased body mass index in the preclinical stage of autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 7, 1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Alhurani RE, Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Mielke MM, Kremers WK, Machulda MM, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Roberts RO (2016) Decline in weight and incident mild cognitive impairment: Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. JAMA Neurol 73, 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moody JN, Valerio KE, Hasselbach AN, Prieto S, Logue MW, Hayes SM, Hayes JP, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2021) Body mass index and polygenic risk for Alzheimer’s disease predict conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 76, 1415–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Meilahn EN, Cauley JA, Tracy RP, Macy EO, Gutai JP, Kuller LH (1996) Association of sex hormones and adiposity with plasma levels of fibrinogen and PAI-1 in postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 143, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.