Abstract

A 30-kDa major outer membrane protein of Ehrlichia canis, the agent of canine ehrlichiosis, is the major antigen recognized by both naturally and experimentally infected dog sera. The protein cross-reacts with a serum against a recombinant 28-kDa protein (rP28), one of the outer membrane proteins of a gene (omp-1) family of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Two DNA fragments of E. canis were amplified by PCR with two primer pairs based on the sequences of E. chaffeensis omp-1 genes, cloned, and sequenced. Each fragment contained a partial 30-kDa protein gene of E. canis. Genomic Southern blot analysis with the partial gene probes revealed the presence of multiple copies of these genes in the E. canis genome. Three copies of the entire gene (p30, p30-1, and p30a) were cloned and sequenced from the E. canis genomic DNA. The open reading frames of the two copies (p30 and p30-1) were tandemly arranged with an intergenic space. The three copies were similar but not identical and contained a semivariable region and three hypervariable regions in the protein molecules. The following genes homologous to three E. canis 30-kDa protein genes and the E. chaffeensis omp-1 family were identified in the closely related rickettsiae: wsp from Wolbachia sp., p44 from the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, msp-2 and msp-4 from Anaplasma marginale, and map-1 from Cowdria ruminantium. Phylogenetic analysis among the three E. canis 30-kDa proteins and the major surface proteins of the rickettsiae revealed that these proteins are divided into four clusters and the two E. canis 30-kDa proteins are closely related but that the third 30-kDa protein is not. The p30 gene was expressed as a fusion protein, and the antibody to the recombinant protein (rP30) was raised in a mouse. The antibody reacted with rP30 and a 30-kDa protein of purified E. canis. Twenty-nine indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA)-positive dog plasma specimens strongly recognized the rP30 of E. canis. To evaluate whether the rP30 is a suitable antigen for serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis, the immunoreactions between rP30 and the whole purified E. canis antigen were compared in the dot immunoblot assay. Dot reactions of both antigens with IFA-positive dog plasma specimens were clearly distinguishable by the naked eye from those with IFA-negative plasma specimens. By densitometry with a total of 42 IFA-positive and -negative plasma specimens, both antigens produced results similar in sensitivity and specificity. These findings suggest that the rP30 antigen provides a simple, consistent, and rapid serodiagnosis for canine ehrlichiosis. Cloning of multigenes encoding the 30-kDa major outer membrane proteins of E. canis will greatly facilitate understanding pathogenesis and immunologic study of canine ehrlichosis and provide a useful tool for phylogenetic analysis.

Canine ehrlichiosis is caused by Ehrlichia canis, an obligatory intracellular bacterium. It was described originally in Algeria in 1935 (7), and it has now been reported throughout the world and at higher frequency in tropical and subtropical regions (13, 15, 32). Canine ehrlichiosis is characterized by fever, depression, anorexia, and weight loss in the acute phase, with laboratory findings of thrombocytopenia and hypergammaglobulinemia (3, 9). A subclinical phase follows the acute phase (5, 12, 28). In the chronic phase, in addition to the clinical signs and laboratory findings of the acute phase, hemorrhages, epistaxis, edema, and hypotensive shock may occur, which are often exacerbated by superinfection with other organisms (3, 9, 16).

Among several protein antigens of E. canis, the proteins in the 30-kDa range were shown to be dominant antigens and consistently recognized by sera from both experimentally and naturally infected dogs in Western blot analysis (14, 25, 26). The proteins of E. canis immunologically cross-react with Ehrlichia chaffeensis major antigens in the 30-kDa range (25). These E. canis and E. chaffeensis proteins were found to be major outer membrane proteins (OMPs) (22). Analysis of a 28-kDa major OMP (P28) gene of E. chaffeensis, one of the 30-kDa-range antigens, and its gene copies revealed that these proteins are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family (22). The rabbit serum against a recombinant E. chaffeensis P28 protein cross-reacted with the 30-kDa protein of E. canis (22).

Dot immunoblot assaying has been developed for serodiagnosis of several infectious agents (4, 10, 11, 30). The advantages of the assay are that an expensive instrument is not required and the interpretation of the results is easy, since positive and negative reactions can be distinguished by the naked eye. However, to be used as the antigen, purification of the organism from infected cells is essential, since E. canis is an obligate intracellular bacterium. Purification of E. canis is time-consuming and expensive, and serial passages of E. canis in the cell culture may produce batch-to-batch variations. Although, no genes of E. canis other than the 16S rRNA gene have thus far been identified, preparation of a recombinant major antigen is expected to greatly improve the serodiagnosis of E. canis infection.

In this study, three genes encoding the 30-kDa OMPs from the E. canis genome were identified. All were found to be homologous and phylogenetically characterized. A recombinant protein of E. canis which was expressed as a fusion protein was found to be highly antigenic. The dot immunoblot assay was developed with the recombinant E. canis protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and purification.

E. canis Oklahoma and E. chaffeensis Arkansas were cultivated in the DH82 dog macrophage cell line and purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation (22) or Sephacryl S-1000 column chromatography (26).

PCR, cloning, and expression.

The sequences of two forward primers, FECH1 and FECH2, were 5′-CGGGATCCGAATTCGG(A/T/G/C)AT(A/T/C)AA(T/C)GG(A/T/G/C)AA(T/C)TT(T/C)TA-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCGAATTCTA(T/C) AT(A/T)AG(T/C)GG(A/T/G/C)AA(A/G)TA(T/C)ATG-3′, corresponding to amino acid positions 6 to 12 and positions 12 to 18, respectively, of the mature 28-kDa protein (P28) of E. chaffeensis (22). These primers have a 14-bp sequence (underlined) at the 5′ end to create an EcoRI site and a BamHI site for insertion into an expression vector. The sequence of a reverse primer, REC1, was 5′-ACCTAACTTTCCTTGGTAAG-3′, complementary to the DNA sequence corresponding to amino acid positions 185 to 191 of the mature P28 of E. chaffeensis (22).

Genomic DNA of E. canis was isolated from Percoll gradient-purified organisms as described elsewhere (22). PCR amplification was performed by using a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA Thermal Cycler (model 480). The 0.6-kb products were amplified with both primer pairs, FECH1-REC1 and FECH2-REC1, and were cloned in the pCRII vector of a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen Co., San Diego, Calif.). The clones obtained by FECH1-REC1 and FECH2-REC1 were designated pCRIIp30 and pCRIIp30a, respectively. Both strands of the insert DNA were sequenced by a dideoxy termination method with an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer.

For expression, the 0.6-kb fragment was excised from the clone pCRIIp30 by EcoRI digestion, ligated into EcoRI site of a pET29a expression vector, and amplified in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLys (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). The clone (designated pET29p30) produced a fusion protein with 35-amino-acid and 21-amino-acid sequences carried from the vector at the N and C termini, respectively.

For purification of a recombinant P30 fusion protein (rP30), the cultivated clone was harvested at 4 h after induction with β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The recombinant protein in the clone pET29p30 was enriched in the pellet by three cycles of centrifugation of the lysate after disruption of the transformant by freezing-thawing and sonication. The final pellet was used as a partially purified rP30 antigen. Affinity-purified rP30 protein was obtained by chromatography with His-Bind Resin (Novagen, Inc.). Briefly, after preparation of the partially purified rP30 antigen, the insoluble protein was extracted with binding buffer (5 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9]), including 6 M urea. After being applied to a Ni+-conjugated column, the recombinant protein was eluted with elution buffer (1 M imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9]) containing 6 M urea. The refolding of the purified protein was achieved by sequential dialysis in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9) containing 4 and 2 M urea and finally in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer only and stored at −80°C until use.

Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNA extracted from the Percoll-purified E. canis (200 ng each) was digested with restriction enzymes, electrophoresed, and transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) by a standard method (27). The 0.6-kb DNA inserts containing partial p30 and p30a genes, cloned in pCRIIp30 and pCRIIp30a, respectively, were separately labeled with [α-32P]dATP by the random primer method with a kit (Amersham), and each labeled fragment was used for Southern blot analysis as a DNA probe. Hybridization was performed at 60°C in Rapid Hybridization buffer (Amersham) for 20 h. The nylon sheet was washed in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC containing 0.15 M sodium chloride and 0.015 M sodium citrate) with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 55°C, and the hybridized probes were exposed to Hyperfilm (Amersham) at −80°C.

Cloning and sequencing of 30-kDa protein gene copies from the E. canis genomic DNA.

The HindIII DNA fragment, which was detected by genomic Southern blot analysis as described above, was inserted into pBluescript II KS(+) vectors, and the recombinant plasmids were introduced into E. coli DH5α. By using the colony hybridization method (27), two positive clones which contained ehrlichial DNA fragments of 3.6 and 7.3 kb were isolated with the 32P-labeled inserts of pCRIIp30 and pCRIIp30a as probes, respectively. DNA sequencing was performed with suitable synthetic primers by the dideoxy termination method described above.

Sequence analysis.

DNA and amino acid sequences were analyzed with the programs DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering America, Ltd., San Bruno, Calif.) and DNASTAR (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.). The amino acid sequences were aligned by using the CLUSTAL method in the DNASTAR program. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by using the PHYLIP software package (version 3.5) (8). An evolutionary distance matrix, generated by using the Kimura formula in the program PROTDIST in the package, was used for construction of a phylogenetic tree by using the unweighted pair-group method of analysis (8). The data were examined by using parsimony analysis (PROTPARS in the PHYLIP). A bootstrap analysis was carried out to investigate the stability of randomly generated trees by using SEQBOOT and CONSENSE in the same package.

Dog plasma and mouse serum.

Totals of 34 and 8 dog blood samples with heparin or EDTA were obtained from the Southwest Veterinary Diagnostic Center (Phoenix, Ariz.) and at the Ohio State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, respectively. All blood specimens collected were centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min, and the plasma samples were used for this study. For Western blot analysis, these plasma samples were preabsorbed three times with pET29a-transformed E. coli at 4°C overnight prior to use. For preparation of the mouse anti-rP30 serum, a male mouse (BALB/c) was intraperitoneally immunized a total of four times at 10-day intervals, once with an equal mixture of the affinity-purified rP30 (30 μg of protein) and Freund’s complete adjuvant (Sigma) and three times with an equal mixture of the protein (30 μg) and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. The mouse was sacrificed 7 days after final immunization, and the serum was prepared from blood collected from the heart.

IFA and Western blot analysis.

Indirect fluorescent antibody assays, (IFA) and Western blot analysis were performed by a procedure described elsewhere (25). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-dog immunoglobulin G (IgG; Organon Teknika Co., Durham, N.C.) and peroxidase-conjugated affinity-purified anti-dog IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) were used at dilutions of 1:200 for IFA and 1:2,000 for Western blot analysis, respectively, as secondary antibodies.

Dot immunoblot assay.

Protein concentrations of purified E. canis and recombinant rP30 antigens were determined by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. These antigens in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl) were adsorbed onto a nitrocellulose membrane by using a dot blot apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.), blocked for 30 min with TBS containing 2% milk, air dried, and stored at −20°C until use. For immunoassays, the antigen bound to a nitrocellulose strip was incubated with the plasma samples, which were diluted 1:1,000 in TBS containing 2% milk for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed three times with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (T-TBS), the strip was incubated with peroxidase-conjugated affinity-purified anti-dog IgG (Kirkegaard) at a dilution of 1:2,000 in TBS containing 2% milk. After being washed with T-TBS, the antibody-bound dot was detected by immersing the strip in a developing solution (0.3% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochrolide [Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan] and 0.05% hydrogen peroxide in 70 mM sodium acetate [pH 6.2]). The color intensity was analyzed by using background correction in image analysis software (ImageQuaNT program; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

GenBank accession number.

The DNA sequences of the p30, p30a, and p30-1 genes of E. canis have been assigned GenBank accession numbers AF078553, AF078555, and AF078554, respectively.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of three 30-kDa protein gene copies of E. canis.

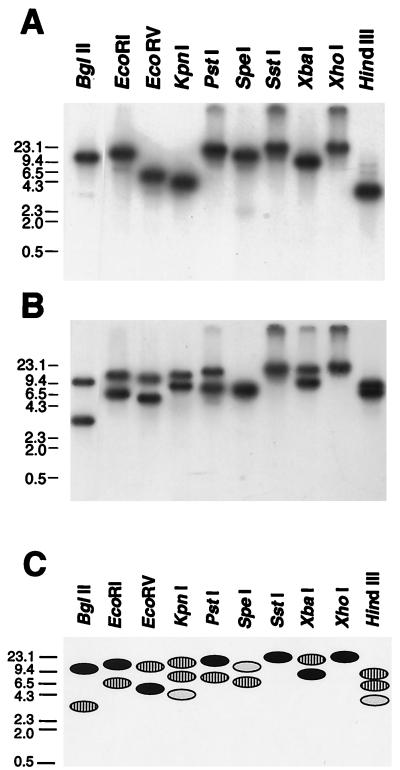

Two 0.6-kb DNA fragments containing partial p30 and p30a genes, amplified by PCR, were cloned and sequenced as described in Materials and Methods. The 0.6-kb DNA, cloned in pCRIIp30, had an open reading frame (ORF) of 579 bp encoding a 193-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 21,175 Da. Another 0.6-kb fragment, cloned in pCRIIp30a, had an ORF of 564 bp encoding a 188-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 21,042 Da. The DNA and predicted amino acid sequences of the partial p30a gene were similar but not identical to those of the partial p30 gene. Genomic Southern blot analysis of E. canis digested with several restriction enzymes revealed one and two DNA fragments which could strongly hybridize to the partial p30 and p30a gene probes, respectively (Fig. 1). These restriction enzymes used do not cut within the p30 and p30a gene probes, and, therefore, the result with the p30a probe indicates that another gene homologous to the p30a is present in the E. canis genome. In BglII, EcoRI, and PstI digestion, the p30 probe hybridized with the upper band of the two p30a-hybridized bands. In EcoRV and XbaI digestion, the p30 probe hybridized with the lower band of the two p30a-hybridized bands. In KpnI, SpeI, and HindIII digestion, the p30 probe hybridized with one or two bands that were different from the p30a-hybridized bands.

FIG. 1.

Genomic Southern blot analysis of E. canis DNA with the partial p30 gene probe (A) and with the partial p30a gene probe (B) and schematic representation of the blotting patterns (C). Numbers indicate molecular sizes in kilobases. Filled dots, bands hybridized with both p30 and p30a probes; striped dots, bands hybridized with p30a probe alone; lightly shaded dots, bands hybridized with p30 probe alone.

Two DNA fragments of 3.6 and 7.3 kb were cloned by colony hybridization with the probes described above from the HindIII-digested genomic DNA of E. canis. Sequencing revealed a complete ORF of 864 bp for the p30 gene in the 3.6-kb fragment and a complete ORF of 861 bp for p30a gene in the 7.3-kb DNA fragment. An additional ORF of 921 bp was found in the 3.6-kb DNA. The DNA sequence of the ORF (designated p30-1) was also similar but not identical to those of the p30 and p30a genes. There are two potential start codons in the p30-1 gene sequence. By comparison with the N-terminal amino acid sequences of p30 and p30a genes, we chose a second ATG as a start codon for phylogenetic analysis. The coding region is 834 bp. The p30-1 and p30 genes were tandemly arranged with an intergenic space of 355 bp in the 3.6-kb fragment like the E. chaffeensis omp-1 family (22). In addition to the result of the genomic Southern blot analysis, this finding showed that at least four homologous genes (p30, p30-1, p30a, and a gene homologous to p30a) exist in the E. canis genome, suggesting that these genes of E. canis are also encoded by a polymorphic multigene family as is the case with E. chaffeensis (22).

Structure of proteins encoded by E. canis multigenes.

Three complete gene copies (p30, p30-1, and p30a) encode 278- to 288-amino-acid proteins with molecular masses of 30,485 to 31,529 Da. The 25-amino-acid sequence at the N termini of P30, P30-1, and P30a (encoded by p30, p30-1, and p30a, respectively) is predicted to be a signal peptide, as described previously (22). The molecular masses of the mature proteins calculated based on the predicted amino acid sequences are 28,750 Da for p30, 27,727 Da for p30-1, and 29,132 Da for p30a.

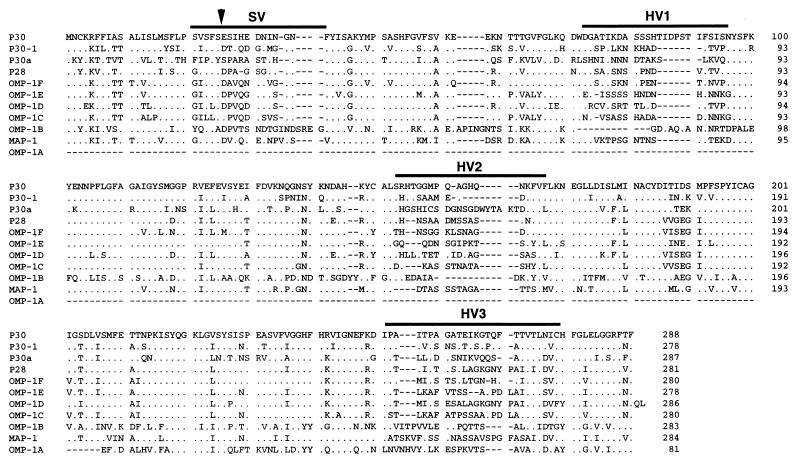

The predicted amino acid sequences of E. canis P30, P30-1, and P30a showed high similarity with those of members in the E. chaffeensis omp-1 gene family (22) and that of major antigen protein 1 (MAP-1) of Cowdria ruminantium (31). These organisms are also serologically cross-reactive (6, 17, 18, 19, 20). The alignment of amino acid sequences of these proteins revealed substitutions or deletions of one or several contiguous amino acid residues throughout the molecules (Fig. 2). The significant differences in sequences among the proteins are observed in the regions designated SV (semivariable region) and HV (hypervariable region). Computer analysis for hydropathy revealed that protein molecules predicted for three E. canis gene copies contain alternative hydrophilic and hydrophobic motifs which are characteristic of typical transmembrane proteins. HV1 and HV2 were located in the hydrophilic regions (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of P30, P30-1, and P30a of E. canis, seven members of E. chaffeensis omp-1 multigene family (P28 and OMP-1A to OMP-1F), and MAP-1 of C. ruminantium (Senegal strain). The sequences of the E. chaffeensis omp-1 gene family and MAP-1 are from the reports of Ohashi et al. (22) and Van Vliet et al. (31), respectively. Aligned positions of identical amino acids with P30 of E. canis are indicated by dots. Gaps (indicated by dashes) were introduced for optimal alignment of all proteins. Bars indicate an SV and three HVs (HV1, -2, and -3). The arrowhead indicate the putative cleavage site of the signal peptide.

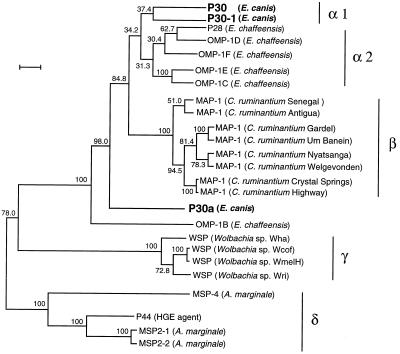

Phylogenetic relationship among the three E. canis 30-kDa proteins and the major OMPs of the closely related rickettsiae based on amino acid sequence similarities.

Recently, several major OMP genes which are closely related to the E. canis 30-kA protein have been cloned from rickettsiae (2, 21–24, 31, 34). The phylogenetic tree consisting of 25 major OMPs of the organisms including P30, P30-1, and P30a of E. canis was constructed from the estimated evolutionary distances (Fig. 3). The overall pattern of the tree reflects the result based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of the rickettsiae. The 23 representatives, except for E. canis P30a and E. chaffeensis OMP-1B, are divided into four groups as follows: E. canis and E. chaffeensis, group α; C. ruminantium, group β; Wolbachia sp., group γ; and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) and Anaplasma marginale, group δ. Group α formed a subcluster of E. canis P30 and P30-1 (group α1), which was separated from another subcluster composed of five E. chaffeensis OMPs (group α2). The similarities between P30 and P30-1 of E. canis in group α1, between groups α1 and α2, between groups α1 and β, between groups α1 and γ, and between groups α1 and δ were 80.2%, 77.3 to 80.6%, 73.9 to 76.4%, 44.0 to 45.1%, and 19.5 to 47.6%, respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, E. canis P30a and E. chaffeensis OMP-1B were far from group α and were located between groups β and γ. The similarities between E. canis P30a and group α1, between P30a and group α2, between P30a and group β, between P30a and group γ, and between P30a and group δ were 70.8 to 71.6%, 71.2 to 73.9%, 65.9 to 67.8%, 41.5 to 43.2%, and 19.5 to 43.1%, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic classification among P30, P30-1, and P30a of E. canis and the major OMPs of the closely related rickettsiae based on amino acid sequence similarities. Evolutionary distance values were determined by the method described by Kimura, and the tree was constructed by the unweighted pair-group method of analysis. Scale bar indicates 10% divergence in amino acid sequences. Bootstrap values from 100 analyses are shown at the branch points of the tree. Bars with symbols indicate representative clusters. The GenBank accession numbers of the major OMP gene sequences of the organisms used in the analysis are as follows: P28 (E. chaffeensis), U72291; OMP-1B to OMP-1F (E. chaffeensis), AF021338; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Senegal strain), I40882, MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Antigua strain), U50830; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Gardel strain), U50832; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Um Banein strain), U50835; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Nyatsanga strain), U50834; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Welgevonden strain), U49843; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Crystal Springs strain), U50831; MAP-1 (C. ruminantium Highway strain), U50833; WSP (Wolbachia sp. Wha strain), AF020068; WSP (Wolbachia sp. Wcof strain), AF020067; WSP (Wolbachia sp. WmelH strain), AF020066; WSP (Wolbachia sp. Wri strain), AF020070; MSP-4 (A. marginale), Q07408; MSP2-1 (A. marginale), U07862; MSP2-2 (A. marginale), U36193; and P44 (HGE agent), AF059181.

TABLE 1.

Similarities among amino acid sequences of E. canis P30, P30-1, and P30a; E. chaffeensis omp-1 family (OMP-1B to OMP-1F and P28); C. ruminantium MAP-1; Wolbachia spp. WSP; HGE agent P44; and A. marginale MSP-4, MSP2-1, and MSP2-2

| Protein | % Amino acid sequence similarity and evolutionary distance for the following proteinsa:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P30 | P30-1 | P30a | P28 | OMP-1F | OMP-1E | OMP-1D | OMP-1C | OMP-1B | MAP-1 (Senegal) | MAP-1 (Antigua) | |

| P30 | 80.2 | 70.8 | 80.6 | 80.5 | 78.6 | 77.8 | 77.5 | 63.2 | 75.4 | 76.2 | |

| P30-1 | 0.38628 | 71.6 | 79.8 | 81.7 | 78.7 | 78.3 | 77.3 | 63.2 | 74.7 | 75.6 | |

| P30a | 0.60811 | 0.60559 | 73.9 | 72.1 | 73.3 | 71.2 | 72.1 | 58.8 | 67.2 | 67.8 | |

| P28 | 0.36288 | 0.40582 | 0.50899 | 85.7 | 82.3 | 86.3 | 81.1 | 63.6 | 76.4 | 77.5 | |

| OMP-1F | 0.37862 | 0.36209 | 0.59907 | 0.27551 | 83.4 | 84.9 | 83.0 | 63.2 | 75.4 | 75.8 | |

| OMP-1E | 0.41426 | 0.42866 | 0.52142 | 0.35465 | 0.32640 | 81.7 | 90.1 | 63.4 | 76.8 | 78.1 | |

| OMP-1D | 0.45193 | 0.46724 | 0.61591 | 0.25793 | 0.28867 | 0.36288 | 81.5 | 63.2 | 73.5 | 74.5 | |

| OMP-1C | 0.45426 | 0.48329 | 0.57469 | 0.39823 | 0.34577 | 0.18285 | 0.37688 | 62.4 | 76.0 | 77.5 | |

| OMP-1B | 0.89214 | 0.87276 | 0.99793 | 0.81397 | 0.83501 | 0.82982 | 0.84498 | 0.89516 | 62.7 | 63.2 | |

| MAP-1 (Senegal) | 0.50490 | 0.51605 | 0.76041 | 0.46987 | 0.50383 | 0.46987 | 0.57453 | 0.50564 | 0.92668 | 93.9 | |

| MAP-1 (Antigua) | 0.47614 | 0.50899 | 0.74635 | 0.46755 | 0.52220 | 0.46096 | 0.57153 | 0.48952 | 0.88842 | 0.09122 | |

| MAP-1 (Gardel) | 0.48606 | 0.49693 | 0.72910 | 0.47185 | 0.51256 | 0.46096 | 0.54403 | 0.48280 | 0.89649 | 0.13499 | 0.11546 |

| MAP-1 (Crystal Springs) | 0.55702 | 0.53478 | 0.78883 | 0.52220 | 0.56563 | 0.49693 | 0.59089 | 0.53368 | 0.93601 | 0.13657 | 0.14142 |

| MAP-1 (Highway) | 0.52891 | 0.52047 | 0.76041 | 0.49443 | 0.54364 | 0.46987 | 0.57594 | 0.50564 | 0.93601 | 0.12383 | 0.12856 |

| MAP-1 (Nyatsanga) | 0.50593 | 0.49693 | 0.76544 | 0.49196 | 0.53368 | 0.46755 | 0.57296 | 0.48952 | 0.91855 | 0.13077 | 0.11963 |

| MAP-1 (Um Banein) | 0.48606 | 0.49693 | 0.72910 | 0.47185 | 0.51256 | 0.46096 | 0.54403 | 0.48280 | 0.89649 | 0.12658 | 0.11963 |

| MAP-1 (Welgevonden) | 0.52629 | 0.50383 | 0.74708 | 0.49877 | 0.53368 | 0.47419 | 0.60290 | 0.48952 | 0.92979 | 0.16080 | 0.14519 |

| WSP (Wha) | 1.57097 | 1.66864 | 1.78274 | 1.59949 | 1.50435 | 1.38174 | 1.61950 | 1.45510 | 1.41776 | 1.58338 | 1.48404 |

| WSP (Wcof) | 1.46262 | 1.62571 | 1.62571 | 1.55195 | 1.40877 | 1.29961 | 1.60271 | 1.41762 | 1.33110 | 1.55897 | 1.53089 |

| WSP (WmelH) | 1.48165 | 1.64952 | 1.64952 | 1.54244 | 1.39991 | 1.31514 | 1.59304 | 1.43572 | 1.34750 | 1.54961 | 1.49206 |

| WSP (Wri) | 1.46435 | 1.66864 | 1.70518 | 1.55687 | 1.46526 | 1.27219 | 1.57654 | 1.39076 | 1.32111 | 1.53292 | 1.47465 |

| P44 | 1.77884 | 1.84928 | 2.04164 | 1.56146 | 1.74020 | 1.64702 | 1.64376 | 1.64702 | 1.64566 | 1.57894 | 1.63909 |

| MSP-4 | 1.37226 | 1.39399 | 1.62744 | 1.38660 | 1.45473 | 1.36494 | 1.45413 | 1.47002 | 1.34294 | 1.23482 | 1.31702 |

| MSP2-1 | 1.50323 | 1.53992 | 1.90757 | 1.40230 | 1.59474 | 1.53455 | 1.40877 | 1.50435 | 1.52758 | 1.53992 | 1.54847 |

| MSP2-2 | 1.52476 | 1.53992 | 1.87540 | 1.40230 | 1.57132 | 1.53455 | 1.40877 | 1.50435 | 1.55019 | 1.51796 | 1.52616 |

| % Amino acid sequence similarity and evolutionary distance for the following proteins:

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP-1 (Gardel) | MAP-1 (Crystal Springs) | MAP-1 (Highway) | MAP-1 (Nyatsanga) | MAP-1 (Um Banein) | MAP-1 (Welgevonden) | WSP (Wha) | WSP (Wcof) | WSP (WmelH) | WSP (Wri) | P44 | MSP-4 | MSP2-1 | MSP2-2 |

| 76.4 | 74.5 | 75.4 | 75.8 | 76.4 | 75.2 | 44.4 | 44.6 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 19.5 | 45.6 | 27.8 | 27.4 |

| 74.7 | 73.9 | 74.3 | 74.7 | 74.7 | 74.5 | 44.0 | 45.1 | 44.8 | 44.6 | 20.5 | 47.6 | 29.3 | 29.1 |

| 67.6 | 65.9 | 66.5 | 66.7 | 67.6 | 67.2 | 41.5 | 43.2 | 42.9 | 42.5 | 19.5 | 43.1 | 24.2 | 24.2 |

| 75.8 | 74.5 | 75.4 | 75.2 | 75.8 | 74.9 | 44.0 | 44.8 | 44.8 | 44.6 | 22.5 | 46.9 | 29.7 | 29.5 |

| 74.5 | 73.3 | 73.9 | 73.9 | 74.5 | 73.9 | 44.6 | 45.9 | 45.9 | 45.3 | 21.1 | 46.2 | 27.8 | 27.8 |

| 76.2 | 75.4 | 76.2 | 76.0 | 76.2 | 75.8 | 45.7 | 46.9 | 46.7 | 46.9 | 22.0 | 47.5 | 28.2 | 28.0 |

| 74.1 | 73.1 | 73.5 | 73.3 | 74.1 | 72.4 | 43.6 | 44.2 | 44.2 | 44.2 | 22.0 | 46.0 | 29.9 | 29.7 |

| 75.8 | 74.5 | 75.4 | 75.6 | 75.8 | 75.6 | 45.3 | 46.1 | 45.9 | 46.1 | 22.0 | 46.6 | 28.6 | 28.4 |

| 63.6 | 63.2 | 63.2 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 62.9 | 45.5 | 45.1 | 44.8 | 45.5 | 19.1 | 45.8 | 26.9 | 26.5 |

| 91.4 | 90.7 | 91.4 | 91.6 | 91.8 | 90.1 | 44.6 | 45.1 | 45.1 | 45.1 | 21.8 | 48.8 | 28.0 | 28.0 |

| 91.8 | 90.7 | 91.4 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 90.3 | 44.8 | 45.1 | 45.3 | 45.3 | 21.8 | 48.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 |

| 92.2 | 92.8 | 94.9 | 99.6 | 93.3 | 44.6 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 20.9 | 46.5 | 27.6 | 27.4 | |

| 0.12928 | 98.9 | 93.1 | 92.4 | 93.1 | 43.4 | 43.4 | 43.4 | 43.2 | 20.0 | 46.1 | 26.7 | 26.7 | |

| 0.11692 | 0.01764 | 93.7 | 93.1 | 93.7 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 43.6 | 20.2 | 46.5 | 27.2 | 27.2 | |

| 0.08788 | 0.11285 | 0.10076 | 94.5 | 95.4 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 20.5 | 46.7 | 28.0 | 27.8 | |

| 0.00693 | 0.12514 | 0.11285 | 0.09570 | 93.3 | 44.6 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 20.9 | 46.5 | 27.6 | 27.4 | |

| 0.11966 | 0.11285 | 0.10076 | 0.08014 | 0.11966 | 44.2 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 20.2 | 46.5 | 27.8 | 27.6 | |

| 1.51972 | 1.73099 | 1.65953 | 1.64538 | 1.51972 | 1.58048 | 86.1 | 86.1 | 90.3 | 12.5 | 42.5 | 22.9 | 22.7 | |

| 1.47157 | 1.59304 | 1.53089 | 1.55897 | 1.47157 | 1.52893 | 0.27243 | 98.3 | 90.9 | 13.6 | 42.1 | 24.0 | 24.0 | |

| 1.46262 | 1.58338 | 1.52153 | 1.54961 | 1.46262 | 1.51972 | 0.26757 | 0.03029 | 90.7 | 13.6 | 42.3 | 23.8 | 23.8 | |

| 1.44526 | 1.64362 | 1.57654 | 1.53292 | 1.44526 | 1.50279 | 0.18429 | 0.17605 | 0.17691 | 13.6 | 43.2 | 24.0 | 23.8 | |

| 1.62813 | 1.74020 | 1.71093 | 1.68253 | 1.62813 | 1.71093 | 2.06354 | 2.15803 | 2.14440 | 2.09032 | 25.7 | 45.5 | 45.2 | |

| 1.33120 | 1.35101 | 1.30992 | 1.31112 | 1.33120 | 1.33120 | 1.72157 | 1.96007 | 1.90199 | 1.72157 | 1.20170 | 35.6 | 34.9 | |

| 1.50996 | 1.57836 | 1.53304 | 1.46817 | 1.50996 | 1.48884 | 1.70865 | 1.79325 | 1.81891 | 1.72741 | 0.83164 | 1.20880 | 95.6 | |

| 1.50996 | 1.55543 | 1.51116 | 1.46817 | 1.50996 | 1.48884 | 1.70865 | 1.75923 | 1.78382 | 1.72741 | 0.84284 | 1.23930 | 0.05064 | |

Values in the upper right half are percent amino acid sequence similarities; those in the lower left half are evolutionary distances.

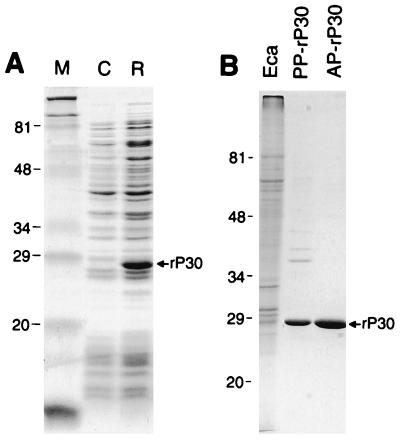

Expression of the E. canis p30 gene.

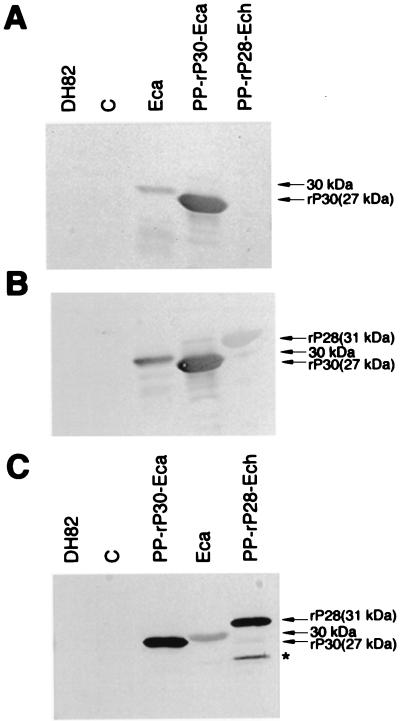

The clone pET29p30 produced a 249-amino-acid fusion protein with a molecular mass of 27,316 Da (Fig. 4A). The recombinant protein (rP30) with minimum E. coli contamination detectable was obtained in the pellet by centrifugation of the lysate of the transformant (Fig. 4B [partially purified antigen]). The rP30 protein further purified by affinity chromatography from this preparation had a single band on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Fig. 4B [affinity-purified antigen]). The immunoreactions of E. canis rP30 with a total of 42 clinical dog plasma specimens were examined. The IgG-IFA titers of 29 plasma samples were 1:20 to 1:10,480. The remaining plasma samples were IFA negative (<1:20). Western blot analysis revealed that all IFA-positive plasma samples recognized the partially purified rP30 fusion protein (27 kDa) and a 30-kDa protein of purified E. canis (one of the blots is shown in Fig. 5A), but none of 13 negative plasma samples reacted with any proteins of partially purified rP30 and purified E. canis (data not shown). Eight of the 29 positive plasma samples reacted weakly with recombinant P28 fusion protein (rP28 [31 kDa]) of E. chaffeensis (22) (one of the blots is shown in Fig. 5B), but the remaining plasma samples did not. A mouse anti-rP30 serum which was prepared by immunization with the affinity-purified antigen reacted with the rP30 antigen, a 30-kDa protein of purified E. canis, and an rP28 of E. chaffeensis (Fig. 5C). Another smaller band which was observed with E. chaffeensis rP28 may be a degradation product of rP28 (asterisk in Fig. 5C), since the plasma sample did not react with E. coli proteins. These results showed that rP30 of E. canis is highly antigenic and that the antigenic epitope is expressed.

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE profiles of a recombinant clone expressing P30 of E. canis (A) and the purified recombinant protein (B). Gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Lanes: M, molecular size markers; C, pET29-transformed E. coli (negative control); R, pET29p30-transformed E. coli (recombinant); Eca, purified E. canis; PP-rP30, partially purified rP30 fusion protein of E. canis; and AP-rP30, affinity-purified rP30 fusion protein. The recombinant rP30 protein is indicated by the arrow. The numbers on the left of each panel indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis with clinical dog plasma with canine ehrlichiosis (A and B) and mouse anti-rP30 serum (C). (A) Dog plasma with a 1:40 IFA titer against E. canis; (B) dog plasma with a 1:1,280 IFA titer. Lanes: DH, DH82 dog macrophage cell (negative control); C, a pET29-transformed E. coli (negative control); Eca, purified E. canis (reactive 30-kDa protein is indicated by arrows in each panel); PP-rP30-Eca, a partially purified rP30 fusion protein (27 kDa) of E. canis; and PP-rP28-Ech, a partially purified rP28 fusion protein (31 kDa) of E. chaffeensis (22). Another smaller reactive band which may be a degradation product of rP28 of E. chaffeensis is indicated by an asterisk.

Dot immunoblot assay with the purified whole organism antigen and the recombinant antigen. (i) Optimum amount of antigen per dot.

Western blot analysis and dot immunoblot assaying in the preliminary experiments supported the interpretation that there are no significant differences between affinity-purified and the partially purified rP30 in specificity and sensitivity (data not shown). If partially purified recombinant protein is suitable for serodiagnosis, it will be more cost-effective. By dot immunoblot assaying we examined in detail whether partially purified rP30 is suitable as an antigen for serodiagnosis.

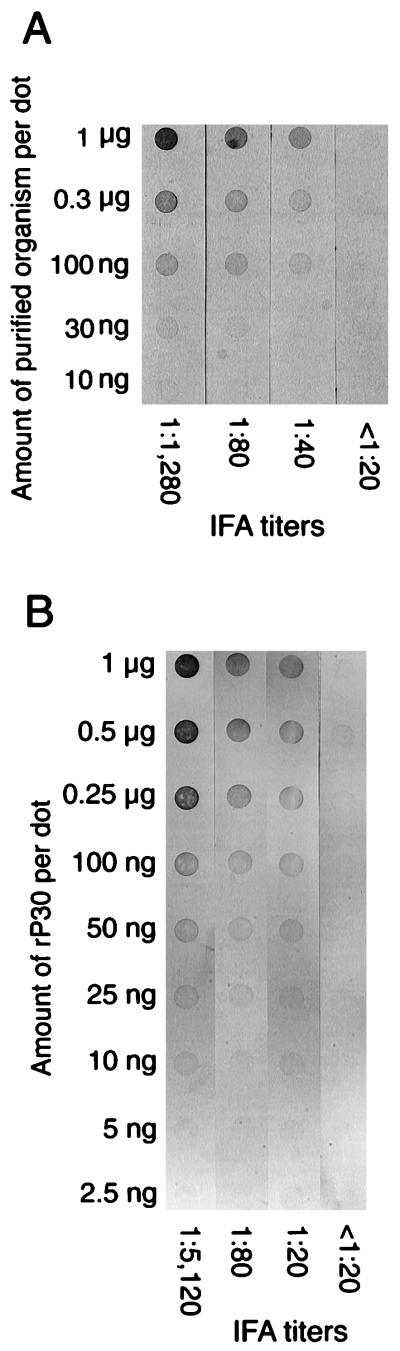

Nitrocellulose strips having serially diluted purified E. canis or partially purified rP30 antigen of E. canis were reacted at a 1:1,000 dilution with dog plasma samples with different IFA titers against E. canis, and the color intensities of the reaction of each dot were compared (Fig. 6). Dots of 0.01 to 1 μg of the purified organisms (Fig. 6A) or dots of 0.025 to 1 μg of rP30 (Fig. 6B) that reacted with positive plasma samples (>1:20 in IFA titer) were clearly distinguishable from those that reacted with negative plasma samples (<1:20) by the naked eye. There was no nonspecific reaction with the negative plasma samples when purified E. canis was used as an antigen; however, a weak nonspecific reaction with IFA-negative plasma was observed in dots of 0.25 to 1 μg of partially purified rP30 antigen. Based on these results, the optimum amounts of antigens per dot were determined to be 1 and 0.5 μg for antigen proteins of purified E. canis and partially purified rP30, respectively. These results show that the partially purified recombinant protein is apparently sufficient as an antigen for serodiagnosis.

FIG. 6.

Optimum amount of antigens for dot blot assaying with purified E. canis antigen (A) or partially purified rP30 antigen (B). Purified organism antigen (10 ng to 1 μg) or rP30 antigen (2.5 ng to 1 μg) was blotted onto the nitrocellulose sheet, reacted with each plasma at a 1:1,000 dilution as primary antibody, and reacted with secondary antibody (peroxidase-conjugated affinity-purified anti-dog IgG antibody) at a 1:2,000 dilution.

(ii) Optimum dilution of antiserum.

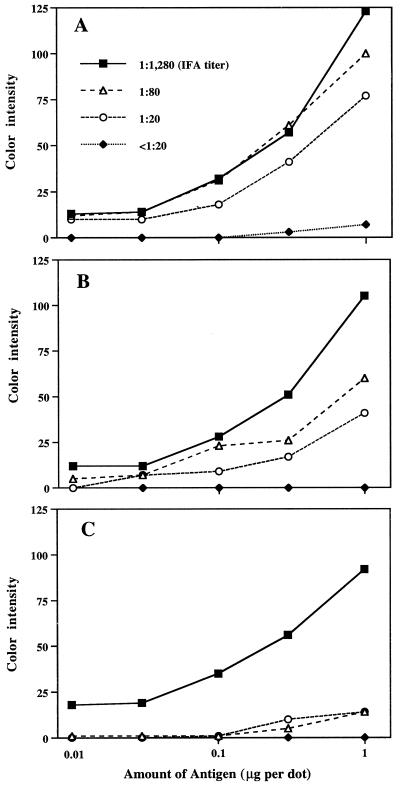

The immunoreactivities of plasma at dilutions of 1:300, 1:1,000, and 1:3,000 were examined with nitrocellulose strips of the purified E. canis antigen as shown in Fig. 6A. The color intensity values were plotted in graphs (Fig. 7). At a 1:300 dilution (Fig. 7A), color development occurred in the dots having an antigen greater than 0.3 μg per dot with IFA-negative plasma. At a 1:3,000 dilution (Fig. 7C), color intensities of all plasma samples were low, especially in the case of positive plasma samples with low IFA titers (1:20 and 1:80). At a 1:1,000 dilution (Fig. 7B), positive plasma with even the lowest IFA titer (1:20) was distinguishable from IFA-negative plasma by the naked eye, especially with 1 μg of purified E. canis antigen per dot (Fig. 6A). The optimum dilution of plasma for testing was, therefore, 1:1,000.

FIG. 7.

Optimum plasma dilutions for dot blot assay. Purified E. canis antigen was blotted as described in the legend to Fig. 6. The antigens were incubated with plasma at dilutions of 1:300 (A), 1:1,000 (B), and 1:3,000 (C). The plasma samples used were the same as those used for Fig. 6A. The color intensity of each dot was determined by using the image software program (ImageQuaNT).

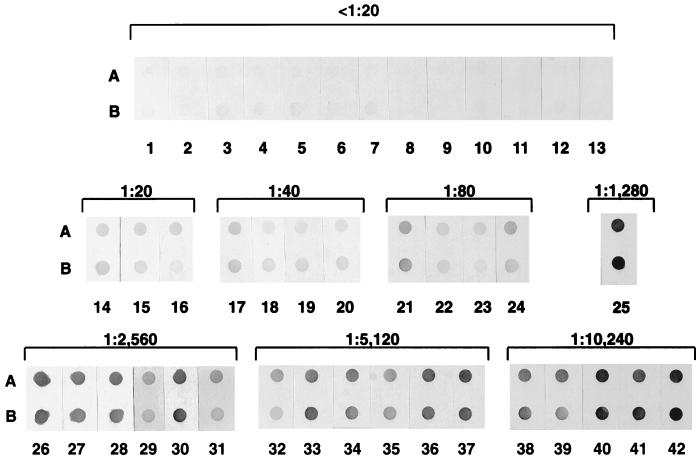

(iii) Examination of clinical dog plasma with purified E. canis and partially purified rP30 antigens.

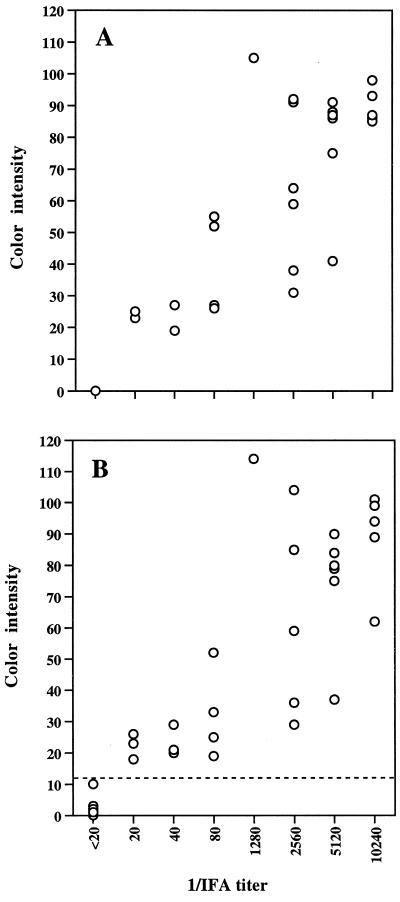

A total of 42 clinical dog plasma samples were examined with 1 μg of purified E. canis antigen per dot and 0.5 μg of partially purified rP30 antigen per dot (Fig. 8). The plasma samples with higher IFA titers showed a darker reaction with both native and recombinant antigens. The color intensities between plasma with IFA titers of >1:20 and IFA-negative plasma were clearly distinguishable by the naked eye. The correlation between IFA titers and color intensity values by the dot immunoblot assay was examined (Fig. 9). The maximum color intensity values of 13 IFA-negative plasma samples (<1:20) were zero (background) in the purified E. canis antigen and 10 in the rP30 antigen. All 29 IFA-positive plasma samples (>1:20) showed color intensity values of greater than 19 in the purified E. canis and 18 in the rP30 antigen. The highest color intensity values were 105 in the purified organism and 114 in the rP30 antigen. In both native and recombinant antigens, color intensity values correlated with IFA titers. The correlation coefficients between IFA titers and color intensities of native and recombinant antigens were 0.71 (P < 0.001) and 0.68 (P < 0.001), respectively. Therefore, it may be possible to estimate an approximate titer of the test serum or plasma by comparing the color densities with those of serially diluted standard serum or plasma.

FIG. 8.

Reaction profiles of purified E. canis antigen (1 μg) (A) and partially purified rP30 antigens (0.5 μg) (B) with 42 plasma samples. Plasma identifications are indicated below each dot. Numbers above brackets indicate the IFA titers of the plasma samples.

FIG. 9.

Correlation between IFA titer (reciprocal dilutions) and color intensity of the dot immunoassay with purified E. canis antigen (A) and partially purified rP30 antigen (B). The color intensities of all dots in Fig. 8 were determined and plotted. Each circle represents one plasma specimen (n = 42). The correlation coefficients were 0.71 (P < 0.001) for graph A and 0.68 (P < 0.001) for graph B. The dashed line in graph B represents the cutoff value, which was determined from the highest color intensity in the immunoreaction with 13 negative plasma samples.

DISCUSSION

The availability of recombinant immunodominant major surface proteins of E. canis will greatly assist in diagnosis and in understanding of the pathogenesis of this intracellular bacterium, such as invasion of host cells, elicitation of the immune response, and mechanisms of the clinical disease. The 30-kDa protein of E. canis was shown to be the immunodominant major OMP, which can be recognized by naturally and experimentally infected dog sera (14, 25, 26). Therefore, the 30-kDa protein is the primary recombinant antigen candidate for use in the serodiagnosis of E. canis infection. The present study is the first report of molecular characterization of 30-kDa major OMPs of E. canis.

Polymorphic multigene families encoding the major OMPs have been identified in E. chaffeensis, the HGE agent, and A. marginale, which are closely related to E. canis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Six copies of the E. chaffeensis p28 gene (omp-1 gene family) are tandemly arranged with intergenic spaces (22), while copies of the HGE agent p44 gene and the A. marginale msp-2 and msp-3 genes are distributed widely throughout the genomes (1, 23, 34). In this study, the 30-kDa proteins of E. canis were also shown to be encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. The two E. canis genes are tandemly arranged with an intergenic space as are members of the E. chaffeensis omp-1 gene family. Although we demonstrated the presence of four gene copies of 30-kDa E. canis proteins in the genome, additional gene copies which are tandemly arranged may exist in three genomic HindIII DNA fragments which hybridized to p30 and p30a probes. Sequence analysis revealed that the 30-kDa proteins (P30, P30-1, and P30a) of E. canis had characteristics of the E. chaffeensis OMP-1 family (22) and C. ruminantium MAP-1 (31). The C. ruminantium MAP-1 has been reported to be cross-reactive to a 27-kDa protein of E. canis (19), although it is unknown whether the 27-kDa protein is identical to P30, P30-1, or P30a of E. canis in this study. Phylogenetic analysis based on the homologs from the closely related rickettsiae revealed that P30 and P30-1 of E. canis are present in the same cluster but that P30a is far from the cluster, suggesting that the multigenes encoding the 30-kDa E. canis proteins are widely divergent. Interestingly, in the phylogenetic tree, the 30-kDa E. canis proteins, the E. chaffeensis OMP-1 family, the HGE agent P44, and A. marginale MSP-2 are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family as described above. However, C. ruminantium MAP-1, Wolbachia sp. WSP, and A. marginale MSP-4 are encoded by a single gene (2, 21–24, 31). The diversities reported among the C. ruminantium MAP-1s and among the Wolbachia sp. WSPs are strain variation (2, 24, 31).

Molecular analysis of E. canis 30-kDa antigens such as ours is important in understanding the antibody responses of animals, because the antigenic diversity may influence the specificity and sensitivity of the serologic assay. Previously, we observed in the Western blot analysis that acute-phase serum (before 30 days postinoculation) from an E. canis-infected dog reacted strongly with a 30-kDa protein but weakly with a 31-kDa protein. However, the reactivity of the chronic-phase serum (after 60 days postinoculation) from the same dog was reversed (strong reaction with the 31-kDa protein and weak reaction with the 30-kDa protein) (14). This might be due to differential expression of the multigene encoding the 30-kDa protein of E. canis during infection. Although it is unknown whether the genes of P30, P30-1, and P30a were expressed by E. canis in tissue culture or in the infected dog, the recombinant P30 protein constructed in this study expressed the antigenic epitope which can react with all IFA-positive dog plasma samples used, suggesting that the antigenic epitope conserved among the 30-kDa protein gene family is expressed. This strongly supports the idea that rP30 is useful as an antigen for serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis.

For serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis, IFA is widely used. However, a fluorescence microscope and trained personnel are required for this test. Furthermore, cell culture of E. canis may produce batch-to-batch variation. A consistent and simple assay that can detect specific antibodies without expensive equipment would be an invaluable aid in serodiagnosis. In the dot immunoblot assay, antibody-positive serum can be distinguished from antibody-negative serum by the naked eye, and if proper color standards are provided, anyone can easily make the final evaluation. The greatest obstacle for the development of this assay is the production of diagnostic antigens sufficient in purity and amount. If recombinant antigens are available, the antigen preparation would be simpler, more consistent, and economical than purified organism antigen preparation. Previously, a dot blot enzyme-linked immunoassay for detecting antibodies to E. canis has been reported (4). However, the crude antigens, freed from host cells by freezing-thawing, were used in that study. Neither recombinant antigens nor the purified antigens (such as organisms purified by Sephacryl S-1000 column chromatography) were used. Additionally, that report contains only one page of description without any data. Therefore, we think our dot immunoblot assay using the recombinant 30-kDa antigen of E. canis would greatly enhance serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis.

Recognition of the lowest positive IFA titer (1:20) plasma by a dot immunoblot assay with 1 μg or less of protein of the whole organism or the recombinant antigen per dot shows that this assay is as sensitive as IFA. Although the specificity of the test, except for cross-reactivity with E. chaffeensis, was not analyzed in this study, as with any other serologic test, dot immunoblot assaying probably cannot distinguish among antigenically cross-reactive members of the tribe Ehrlichieae. However, the use of recombinant E. canis antigen gave greater sensitivity than the use of recombinant E. chaffeensis antigen for serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. Western blot analysis revealed that 8 of 22 IFA-positive plasma samples slightly cross-reacted with recombinant 28-kDa protein of E. chaffeensis. This weak cross-reactivity is not a potential problem for clinics, since treatment is the same for all of the ehrlichial agents.

In dot immunoblot assays of 29 IFA-positive plasma samples, 5 had color intensities of the purified organism antigen greater or lesser than those of the recombinant antigens. Additional major immunodominant proteins of Ehrlichia spp. are heat shock proteins (HSPs) (29, 33). Consequently, when anti-HSP antibody or antibody against protein antigen other than P30 is present in the plasma, whole organism antigens would give an immunoreaction stronger than that of the recombinant protein. On the contrary, when anti-P30 antibody is dominant in the plasma, the reaction with the recombinant protein would be stronger than that with the whole organism antigen. More importantly, the recombinant antigen-dot blot assay could clearly detect all of the 29 IFA-positive plasma samples. Furthermore, between native and recombinant antigens, no significant difference was observed in the correlation coefficient between IFA titers and the blot color intensity. Therefore, the rP30 antigen-immunodot blot assay offers advantages over the other serodiagnostic tests in general availability, ease of handling, and accuracy in the serodiagnosis of E. canis infection. Additionally, although it was not described in this paper, this E. canis recombinant antigen can be applied to enzyme-linked immunosorbent plate assays or other serodiagnostic assays as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by an Ohio State University canine research grant and grant RO1 AI33123 from National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman A R, Palmer G H, McGuire T C, McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Barbet A F. Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 3 is encoded by a polymorphic, mutigene family. Infect Immun. 1997;65:156–163. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.156-163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braig H R, Zhou W, Dobson S L, O’Neill S L. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2373–2378. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2373-2378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhles W C, Huxsoll D L, Ristic M. Tropical canine pancytopenia: clinical, haematologic, and serologic, and serologic response of dogs to Ehrlichia canis infection, tetracycline therapy, and challenge inoculation. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:358–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadman H F, Kelly P J, Matthewman L A, Zhou R, Mason P R. Comparison of the dot-blot enzyme linked immunoassay with immunofluorescence for detecting antibodies to Ehrlichia canis. Vet Rec. 1994;135:362. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.15.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codner E C, Farris-Smith L L. Characterization of the subclinical phase of ehrlichiosis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson J E, Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fishbein D B. Serologic diagnosis of human ehrlichiosis using two E. canis isolates. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:564–567. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donatien A, Lestoquard F. Existence and algerie d’une rickettsia du chien. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1935;28:418–419. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-phylogeny inference package (version 3.3) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene C E, Harvey J W. Canine ehrlichiosis. In: Greene C E, editor. Clinical microbiology and infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1990. pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heberling R L, Kalter S S. Rapid dot immunobinding assay on nitrocellulose for viral antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:109–113. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.1.109-113.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heberling R L, Kalter S S, Smith J S, Hildebrand D G. Serodiagnosis of rabies by dot immunobinding assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1262–1264. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.7.1262-1264.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huxsoll D L, Hilldebrandt P K, Nims R M, Walker J S. Tropical canine pancytopenis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1970;157:1627–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Immelman A, Button C. Ehrlichia canis infection (tropical canine pancytopelia or canine rickettsiosis) J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1973;44:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iqbal Z, Rikihisa Y. Reisolation of Ehrlichia canis from blood and tissues of dogs after doxycycline treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1644–1649. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1644-1649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klopfer U, Nobel T A. Canine ehrlichiosis (tropical canine pancytopenia) in Israel. Refu Vet. 1972;29:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuehn N F, Gaunt S D. Clinical and hematologic findings in canine ehrlichiosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logan L L, Holland C J, Mebus C A, Ristic M. Serological relationship between Cowdria ruminantium and certain Ehrlichia spp. Vet Rec. 1986;119:458–489. doi: 10.1136/vr.119.18.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda K, Markowitz N, Hawley R C, Ristic M, Cox D, McDade J E. Human infection with Ehrlichia canis, a leukocytic rickettsia. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:853–856. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704023161406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahan S M, Tebele N, Mukwedeya D, Semu S, Nyathi C B, Wassink L A, Kelly P J, Peter T, Barbet A F. An immunoblotting diagnostic assay for heat water based on the immunodominant 32-kilodalton protein of Cowdria ruminantium detects false positive in field sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2729–2737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2729-2737.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDade J E. Ehrlichiosis—a disease of animals and humans. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:609–617. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberle S M, Barbet A F. Derivation of the complete msp4 gene sequence of Anaplasma marginale without cloning. Gene. 1993;136:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90482-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohashi N, Zhi N, Zhang Y, Rikihisa Y. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:132–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.132-139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer G H, Eid G, Barbet A F, McGuire T C, McElwain T F. The immunoprotective Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 is encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3808–3816. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3808-3816.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy R G, Sulsona C R, Harrison R H, Mahan S M, Burridge M J, Barbet A F. Sequence heterogeneity of the major antigenic protein 1 genes from Cowdria ruminantium isolates from different geographical areas. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:417–422. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.4.417-422.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fox J C. Western immunoblot analysis of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. canis or E. ewingii infection of dogs and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2107–2112. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2107-2112.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fox J C, Siregar A G, Pasaribu F H, Malole M B. Analysis of Ehrlichia canis and a canine granulocytic Ehrlichia infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:143–148. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.143-148.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Maniatis T, Fritsch E F. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson E H, Clothiw E R, Ristic M. Ehrlichia canis infection in a dog in Virginia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1975;172:63–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sumner J W, Sims K G, Jones D C, Anderson B E. Ehrlichia chaffeensis expresses an immunoreactive protein homologous to the Escherichia coli GroEL protein. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3536–3539. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3536-3539.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urakami H, Yamamoto S, Tsuruhara T, Ohashi N, Tamura A. Serodiagnosis of scrub typhus with antigens immobilized on nitrocellulose sheet. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1841–1846. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1841-1846.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Vliet A H M, Jongejan F, van Kleef M, van der Zeijst B A M. Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and expression of the gene encoding the immunodominant 32-kilodalton protein of Cowdria ruminantium. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1451–1456. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1451-1456.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkins J H, Bowden R S T, Wilkinson G T. A new canine syndrome. Vet Rec. 1967;81:57–58. doi: 10.1136/vr.81.2.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Ohashi N, Lee E H, Tamura A, Rikihisa Y. Ehrlichia sennetsu groEL operon and antigenic properties of the GroEL homolog. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]