Summary

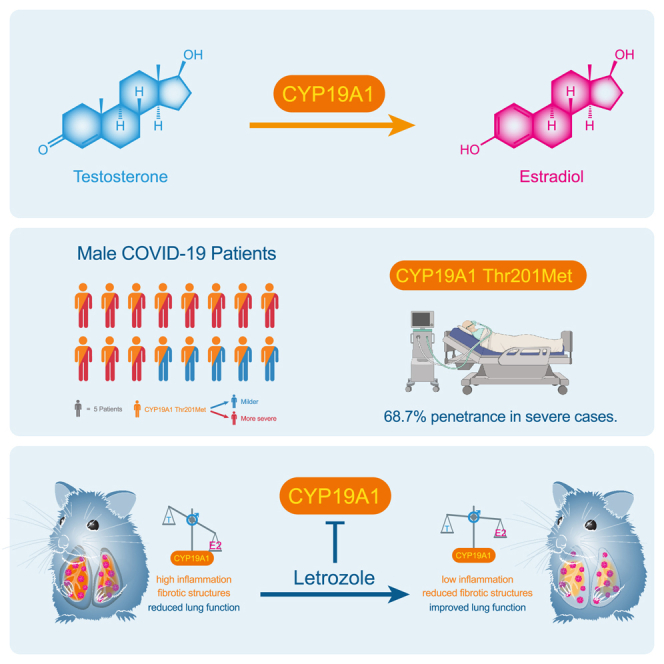

Male sex represents one of the major risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcome. However, underlying mechanisms that mediate sex-dependent disease outcome are as yet unknown. Here, we identify the CYP19A1 gene encoding for the testosterone-to-estradiol metabolizing enzyme CYP19A1 (also known as aromatase) as a host factor that contributes to worsened disease outcome in SARS-CoV-2-infected males. We analyzed exome sequencing data obtained from a human COVID-19 cohort (n = 2,866) using a machine-learning approach and identify a CYP19A1-activity-increasing mutation to be associated with the development of severe disease in men but not women. We further analyzed human autopsy-derived lungs (n = 86) and detect increased pulmonary CYP19A1 expression at the time point of death in men compared with women. In the golden hamster model, we show that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes increased CYP19A1 expression in the lung that is associated with dysregulated plasma sex hormone levels and reduced long-term pulmonary function in males but not females. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters with a clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor (letrozole) improves impaired lung function and supports recovery of imbalanced sex hormones specifically in males. Our study identifies CYP19A1 as a contributor to sex-specific SARS-CoV-2 disease outcome in males. Furthermore, inhibition of CYP19A1 by the clinically approved drug letrozole may furnish a new therapeutic strategy for individualized patient management and treatment.

Keywords: COVID-19, male sex, CYP19A1, testosterone, estradiol, letrozole, lung health

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CYP19A1 Thr201Met shows a penetrance of 68.7% in severely ill male COVID-19 patients

-

•

CYP19A1 is highly expressed in the lungs of deceased male COVID-19 patients

-

•

CYP19A1 is associated with sex hormone imbalance in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

-

•

CYP19A1 inhibition improves long-term lung health in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

Stanelle-Bertram et al. identify a CYP19A1-activity-increasing gene variant in male patients with severe COVID-19. Increased pulmonary CYP19A1 expression is associated with dysregulated sex hormone levels and impaired lung function in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters. The clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole improves long-term lung health in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has continued to threaten the human population since its first emergence in China. To date, approximately 764 million people have been infected and ∼6.8 million have died worldwide since the pandemic declaration on March 11, 2020 (as of July 2023).1 Retrospective analysis of epidemiologic data has revealed that male sex, older age, and underlying metabolic diseases such as obesity pose high risks for fatal COVID-19.2,3,4,5,6 Increased COVID-19 case-fatality rate in males is not reflected by increased incidence compared to females.3,4,7 Thus, it is unlikely that male prevalence in COVID-19 mortality can be explained by elevated susceptibility to viral infection.

Factors that mediate sex disparity in COVID-19 outcome might include a complex interaction of biological sex differences (e.g., genes, sex hormones) and/or gender aspects (e.g., social behavior).6,8 Sex differences of genetic origin are constant throughout life irrespective of age or comorbidity. Sex differences involving sex hormones (e.g., testosterone, estradiol) are dynamic and may change with increasing age and/or metabolic comorbidities.9

Several independent studies highlighted that men hospitalized with COVID-19 present testosterone levels significantly below age-adjusted reference values.10,11,12,13 Moreover, low testosterone levels were repeatedly reported in independent cohorts to present a poor prognostic marker in COVID-19 males.10,12,13,14 In general, low testosterone levels were associated with the highest risks of requiring mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, or fatal outcome in several independent studies.10,13 However, after recovery from COVID-19, total testosterone levels increased over time in men, although at 7-month follow-up ∼50% still had testosterone levels below healthy reference values.14 Moreover, 1 year later ∼30% of men who recovered from COVID-19 still showed low testosterone levels suggesting manifesting hypogonadism.15 Long-term hypogonadism in men is associated with elevated morbidity and mortality in general, also independently of COVID-19,16 which, however, seems to induce and promote sustained hypogonadism. This hypothesis is further strengthened by studies reporting that recovery from hypogonadism is strongly associated with COVID-19 survival in male patients, while failure to reinstate physiological testosterone levels is associated with COVID-19 death.17 In some studies where the assessed hormone profile also included the measurement of additional hormones, low testosterone levels were reported to be associated with elevated estradiol levels in parallel, which were both predictive of ICU admission and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment in COVID-19 men.11,13 Thus, there is increasing evidence that dysregulated sex hormone levels are associated with COVID-19 sex disparities. However, underlying mechanisms, as well as the nature of their involvement being either associative or causal, remain elusive.

Sex hormones may act as important regulators of host cell immunity and exert functions far beyond reproduction. Intracellular androgen and estrogen receptors act as transcription factors by binding to hormone response elements of many genes, thereby regulating cell responses to various environmental changes. Cell-surface-bound androgen and estrogen receptors may additionally affect host responses. Both intracellular and cell-surface-mediated sex hormone receptors may upon activation affect local cell-to-cell signaling (paracrine effects) or systemic hormone signaling pathways via the blood system (endocrine effects).18

In the last decades, evidence has grown that sex hormones play a pivotal role in lung health. Sex differences are known in various lung diseases, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis.19 Research in preterm neonates, where respiratory distress is one of the major causes of death, highlighted a protective role of androgens in lung development.20 Conversely, clinical and experimental studies identified an inflammatory function for estrogens and their metabolites, such as estradiol.5,21 Physiological changes in sex hormone levels, such as those occurring during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause, were associated with changes in lung function.22,23

In this study, we sought to identify molecular pathways involved in sex disparities in COVID-19. Therefore we analyzed, in a sex-dependent fashion, whole-exome sequences from large human COVID-19 cohorts to look for alterations in key enzymes involved in sex hormone metabolism. Furthermore, we quantified expression levels of the identified major sex hormone metabolizing enzyme in the lungs of patients who died of COVID-19. Seeking for causalities, we used the golden hamster model as a widely validated preclinical small animal model to study SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. As a result, combining human and animal data, we identified CYP19A1 (the testosterone-to-estradiol converting enzyme) as a crucial factor of severe disease outcome upon SARS-CoV-2 infection in males. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals with the clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole improved long-term lung health in males, suggesting letrozole as a promising drug candidate for further assessment regarding individualized therapy in humans.

Results

CYP19A1-activity-increasing mutation Thr201Met is associated with the development of severe COVID-19 in male patients

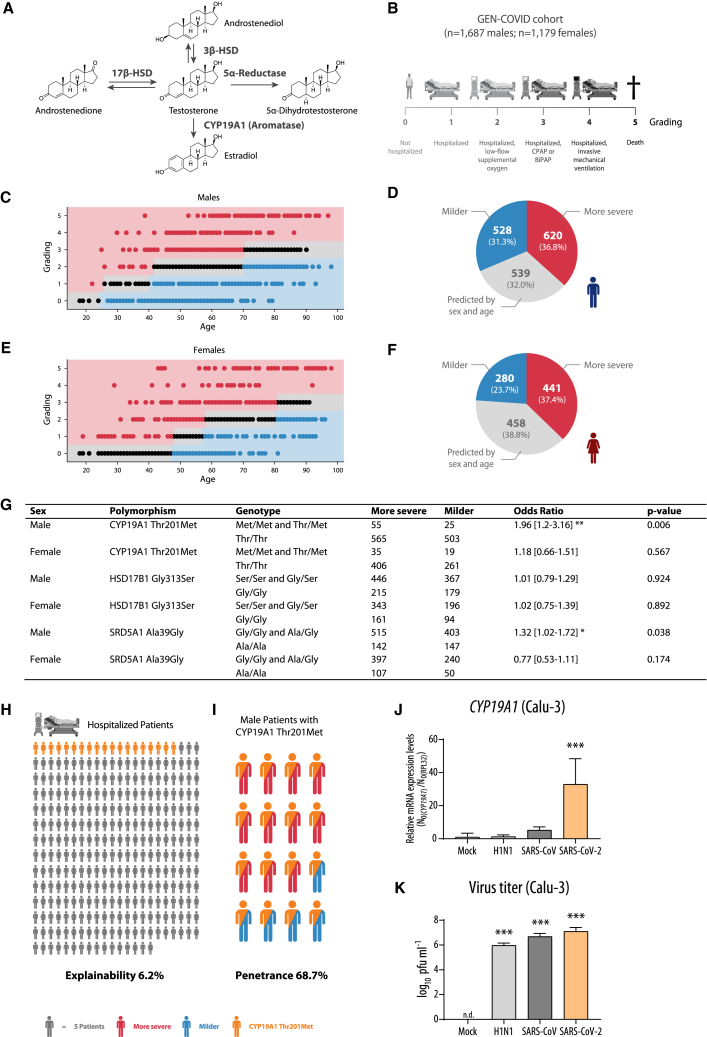

There is ample clinical evidence that low plasma testosterone levels pose a poor prognostic marker for men diagnosed with COVID-19.11,12,13,14,17 However, mechanistic insights into how SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with testosterone dysregulation in males are lacking. Low testosterone levels may result, for example, from alterations in its direct metabolism that involves major key enzymes. Testosterone is metabolized from its precursors androstenedione or androstenediol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) and 3β-HSD, respectively. Testosterone is further metabolized to 5α-dihydrotestosterone by 5α-reductase or is converted to the female sex hormone estradiol by CYP19A1 (also known as aromatase) (Figure 1A). Polymorphisms in these testosterone-metabolizing enzymes were previously reported as leading to low circulating testosterone levels in men.24,25,26,27 Thus, we hypothesized that variations in testosterone metabolic pathways may affect sex-dependent COVID-19 outcome.

Figure 1.

Association analysis of CYP19A1 gene variation in whole-exome sequencing data of the GEN-COVID cohort

(A) Overview of testosterone metabolism.

(B) Characteristics and COVID-19 severity grading of the GEN-COVID cohort (n = 2,866 patients).

(C and E) Ordered logistic regression (OLR) model in male (C) and female (E) patients, fitted using age to predict the ordinal grading (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) dependent variable. Subjects falling above (severe), below (mild), or matching (intermediate) the expected treatment outcomes according to age are shown as red, blue, and black dots, respectively.

(D and F) Pie charts representing the number of male (D) and female (F) patients falling into “milder,” “more severe,” and “predicted by sex and age” categories.

(G) Association analysis between low frequency and common variants present in genes involved in testosterone metabolism and COVID-19 severity.

(H and I) Graphical presentation of explainability (H) and penetrance (I) under a monogenic model for the Thr201Met CYP19A1 variant.

(J and K) CYP19A1 mRNA expression levels (J) and virus titers (K) in Calu-3 cells control-treated (Mock) or infected with H1N1 influenza A virus, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 (multiplicity of infection = 0.5) at 24 h post infection (p.i.). A merge of three independent biological replicates, performed in technical triplicates, is shown. Relative CYP19A1 mRNA expression values in mock-treated cells were set to n.d. (not detectable).

Values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. In (G), (J), and (K) statistical significance was assessed by chi-squared test or one-way ANOVA showing significant differences between mock and infected cells (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed human exome data obtained from 2,866 SARS-CoV-2-positive male and female patients (GEN-COVID; https://sites.google.com/dbm.unisi.it/gen-covid)28 regarding polymorphisms in the genes 17β-HSD, 3β-HSD, 5α-Reductase, and CYP19A1 involved in testosterone metabolism (Figure 1A). We applied a machine-learning approach in combination with a Boolean representation of whole-exome sequencing (WES) data as described previously28,29 to predict COVID-19 severity defined according to World Health Organization criteria (Figure 1B), which are further presented for males (Figures 1C and 1D) and females (Figures 1E and 1F). One low-frequency (minor allele frequency [MAF] from 1% to 5%) variant Thr201Met and two common (MAF >5%) variants (Gly313Ser and Ala39Gly, respectively) in CYP19A1, HSD17B1, and SRD5A1 genes, all involved in testosterone metabolism, appeared among the features used by the model to predict severity after adjusting for age. Among the variants within these genes, the SRD5A1 Ala39Gly and the CYP19A1 Thr201Met variant were significantly associated with COVID-19 severity in males compared to females. However, the CYP19A1 Thr201Met variant showed the strongest association with COVID-19 severity with an odds ratio of 1.96 in males (95% confidence interval, 1.2–3.16; p value, 0.006) (Figure 1G).

Overall, the Thr201Met variant is expected to contribute to severe COVID-19 in up to 6.2% of all hospitalized male and female patients (Figure 1H). Remarkably, in male patients, the Thr201Met variant showed a calculated penetrance under a monogenic model of 68.7% (Figure 1I). The Thr201Met variant in CYP19A1 was previously described to increase CYP19A1 enzyme (aromatase) activity in general, resulting in enhanced metabolism of testosterone to estradiol.30

In summary, analysis of human genetic data strongly suggest that particularly male patients who carry the CYP19A1 (aromatase)-activity-increasing variant Thr201Met, irrespective of age or other confounders, have a high risk of developing severe COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 infection increases CYP19A1 transcription in lung cell cultures

We next sought to assess whether the expression of the CYP19A1 gene, in addition to the identified genetically fixed CYP19A1-activity-increasing mutation, might be additionally affected by viral infection. This would suggest that besides a fixed genetic component, another dynamic component, such as viral infection, could further affect CYP19A1 function. To assess this hypothesis, we infected human lung cells (Calu-3) with SARS-CoV-2 or with SARS-CoV or H1N1 influenza A virus as controls. CYP19A1 mRNA expression was increased up to ∼40-fold in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells but not in SARS-CoV-infected or H1N1 influenza virus-infected lung cells (Figure 1J), despite similar replication efficacies (Figure 1K).

This finding indicates that SARS-CoV-2 has evolved specific mechanisms not observed in its ancestor or an unrelated respiratory pathogen to upregulate CYP19A1 expression in the lung, which could increase the risk for severe disease outcome in addition to the presence of CYP19A1-activity-increasing mutations detected in COVID-19 patients.

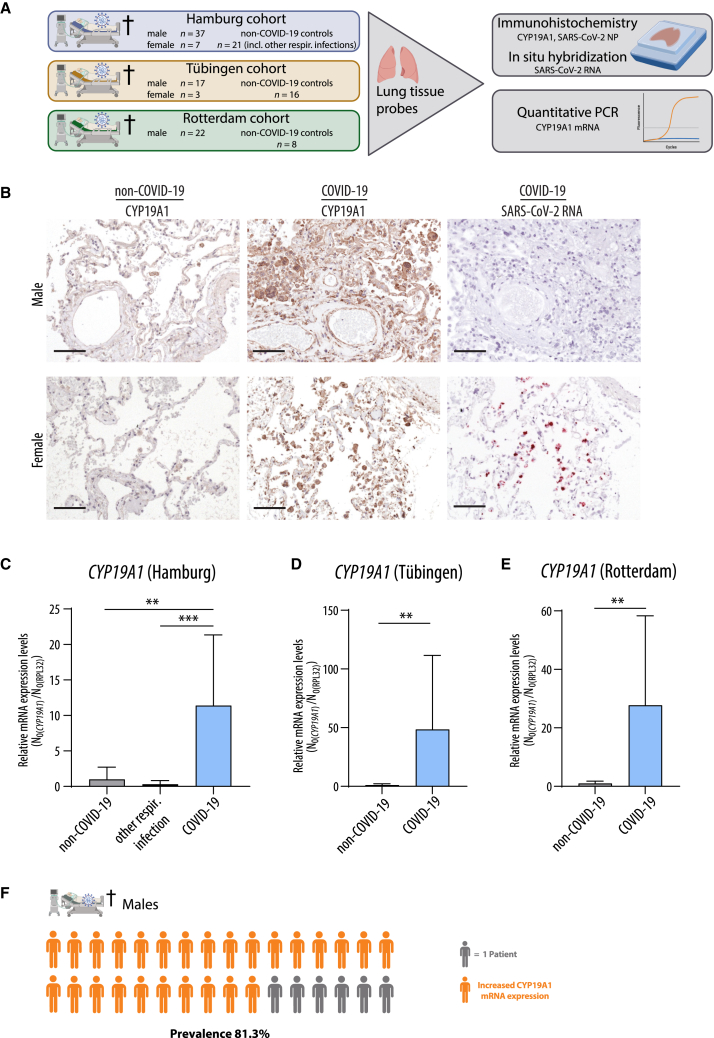

CYP19A1 mRNA is highly expressed in autopsy-derived lung tissues of male COVID-19 patients

To assess whether increased CYP19A1 transcription can also be detected in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, we analyzed autopsy-derived lung material from males and females who died of COVID-19 (n = 86). Therefore, we used three independent study sites for autopsies (Figure 2A). As controls, we analyzed lung material obtained from men and women who were never diagnosed positive for SARS-CoV-2 by qRT-PCR but were diagnosed to have died of other respiratory infections (“other resp. infection”) or for other reasons (“non-COVID-19”).

Figure 2.

CYP19A1 expression in the lungs of fatal COVID-19 cases

(A) Experimental setup for detecting CYP19A1 protein and mRNA expression levels in deceased COVID-19 patients and controls from three different study sites.

(B) Detection of CYP19A1 protein expression (immunohistochemistry) and SARS-CoV-2 RNA (in situ hybridization) in the lungs from deceased male and female COVID-19 patients or non-COVID-19 controls (representative pictures shown from the University Hospital Tübingen cohort). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(C–E) CYP19A1 mRNA expression levels in the lungs of deceased male COVID-19 patients, non-COVID-19 controls, and/or deceased patients with other respiratory infections at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf (C) (non-COVID-19, n = 3; other respiratory infections, n = 11; COVID-19, n = 12), at the University Hospital Tübingen (D) (non-COVID-19, n = 8; COVID-19, n = 9), and at the Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam (E) (non-COVID-19, n = 4; COVID-19, n = 11). Relative CYP19A1 mRNA expression values in non-COVID-19 males were set to 1. Values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney test (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

(F) Visualization of percentage of males who died of COVID-19 with increased pulmonary CYP19A1 expression at the time of death.

At all three study sites (Hamburg, Tübingen, and Rotterdam), CYP19A1 was abundantly expressed in the lungs of COVID-19 males compared to those who died of other respiratory infections or other reasons not related to COVID-19 (Figures 2B–2E). In COVID-19 females, only in two cases was CYP19A1 expression detectable in cells that were still positive for SARS-CoV-2 antigen or RNA (Figure 2B and data not shown). However, owing to the overall very low number of female COVID-19 cases, conclusive interpretation regarding CYP19A1 expression in the female lung is not entirely possible.

In general, CYP19A1 was expressed in epithelial and endothelial cells but most profoundly in macrophages at all three independent study sites. Consecutive staining of the dissected lungs revealed still highly CYP19A1-expressing macrophages in COVID-19 males, albeit SARS-CoV-2 antigen and RNA was expressed at low levels or was no longer detectable at the time point of death (Figure 2B). On the other hand, consecutive staining in COVID-19 females shows SARS-CoV-2 RNA-positive macrophages overlaid with CYP19A1-expressing macrophages (Figure 2B). Quantification of CYP19A1 mRNA levels revealed a transcriptional increase up to ∼10-fold in the male COVID-19 Hamburg cohort, up to ∼50-fold in the lungs of deceased COVID-19 males in the Tübingen cohort, and up to ∼20-fold in the male COVID-19 Rotterdam cohort (Figures 2C–2E).

These findings show that CYP19A1 is abundantly expressed on the mRNA and protein level in the lungs of men who died of COVID-19, with a prevalence of 81.3% (Figure 2F). Thus, CYP19A1 expression seems to be still persisting at the time of death, even when most of the virus is already cleared from the lung.

CYP19A1 transcription is highly induced upon SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lung and lung macrophages of male hamsters

CYP19A1 is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and is expressed in a wide range of tissues, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, the vascular wall, and macrophages, in various mammalian species.31,32,33 The CYP19A1 gene contains predicted binding sites for key transcription factors, e.g., nuclear factor κB and STAT1, -3, -4, and -6 (Figure 3A). In addition, the CYP19A1 promoter contains binding sites for sex-hormone-responsive elements, e.g., the androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptors (ESR-α/-β), and progesterone receptors (PR-α/-β).34,35,36,37,38 (Figure 3A). To study possible causalities between CYP19A1 and COVID-19, we used the golden hamster model to mimic key aspects of COVID-19.

Figure 3.

CYP19A1 expression in the lung of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters

(A) Binding sites for transcription factors in the four promoter regions (P1, P2, P3, and P4) of the CYP19A1 gene.

(B) Quantification of CYP19A1-expressing tissue in the lungs of control-treated (PBS) male and female hamsters (n = 5). Data are shown as a box-and-whisker plot.

(C) Weight loss of male and female hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 (n = 10).

(D and G) CYP19A1 mRNA expression levels measured at day 3 p.i. in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected and control-treated (PBS, Poly(I:C)) male (D) and female (G) golden hamsters (n = 10).

(E, F, H, and I) IL-6 (E and H) and CYP19A1 (F and I) mRNA expression levels in lung macrophages isolated from uninfected male (E and F) or female (H and I) hamsters upon ex vivo PBS or Poly(I:C) treatment (male, n = 11; female, n = 8). Relative mRNA expression values in PBS-treated hamsters or macrophages were set to 1.

Values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney test, unpaired/paired Student’s t test, or one-way ANOVA (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

First, we assessed CYP19A1 expression in the lungs of male and female golden hamsters. We detected increased CYP19A1 protein expression in the male lung compared to the female lung (Figures 3B and S1), in line with previous reports that CYP19A1 is expressed more abundantly in males than in females.39 Next, we infected male and female hamsters with the same virus dose, using the moderate COVID-19 model in golden hamsters.40,41 During the first 6 days of acute infection, weight loss was comparable between males and females (Figure 3C). However, during the recovery phase from day 7 until day 14 post infection (p.i.), infected males recovered more slowly than females. While infected females regained their initial weight on day 14 p.i., infected males still showed reduced body weight (Figure 3C).

In the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters, CYP19A1 transcription increased up to ∼15-fold compared to animals treated with the immunostimulant poly(I:C) or PBS as control at day 3 p.i. (Figure 3D). In the lungs of virus-infected hamsters, cytokines and chemokines were generally induced to similar levels in both sexes (Figure S2). In lung macrophages isolated from uninfected male hamsters, we were able to induce IL-6 expression upon ex vivo poly(I:C) treatment as detected in SARS-CoV-2-infected lungs (Figures 3E and S3). In line with this, IL-6 induction correlated with CYP19A1 mRNA expression in a poly(I:C)-concentration-dependent manner in male lung macrophages (Figures 3F and S3). In lungs of female hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2, CYP19A1 transcription increased up to ∼5-fold compared to uninfected females on day 3 p.i. (Figure 3G). In lung macrophages isolated from uninfected females, we were able to induce IL-6 upon ex vivo poly(I:C) treatment in a concentration-dependent manner similarly to males (Figure 3H). However, CYP19A1 transcription could not be induced in female lung macrophages treated with poly(I:C).

These data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection specifically induces CYP19A1 transcription in the male lung while not affecting the expression of other testosterone-converting enzymes (Figure S4). Additional controls, using cells of non-respiratory origin, further strengthened the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 infection upregulates CYP19A1 transcription exclusively in the respiratory tract (Figure S5).

Increased respiratory CYP19A1 transcription is associated with low testosterone and high estradiol levels in the plasma of SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

To assess whether differential CYP19A1 induction in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals is associated with alterations in circulating sex hormone levels, we quantified testosterone and estradiol levels in the plasma of male and female hamsters at various time points after viral infection.

In infected male hamsters, testosterone levels dropped on day 3 p.i. compared to levels prior to infection by 5-fold, started to recover on day 6 p.i., and were fully recovered on day 14 p.i. compared to males treated with poly(I:C) or PBS (Figure 4A). Virus replication in the male lungs was negatively associated with testosterone levels. Expression of androgen receptors (AR, ZIP-9) was not affected in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters on day 3 p.i. or in poly(I:C)-stimulated lung macrophages as compared to controls (PBS, poly(I:C)) (Figures 4B–4E). Conversely, estradiol levels increased in the plasma of infected male animals on day 3 p.i. compared to PBS-treated groups by 13-fold, remained elevated on day 6 p.i., and had mostly recovered on day 14 p.i. (Figure 4F). Estradiol levels were positively associated with virus titers in the lung. Estrogen receptor (ESR-α, ESR-β) expression was significantly changed in virus-infected groups. ESR-α expression was slightly reduced and ESR-β was strongly induced in the lungs of male hamsters upon SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figures 4G and 4H). In lung macrophages of male hamsters, ESR-α levels were not affected, while ESR-β expression was strongly reduced (Figures 4I and 4J).

Figure 4.

Sex hormones and sex hormone receptor expression in SARS-CoV-2-infected lungs as well as lung macrophages of hamsters

(A, F, K, and P) Testosterone (A and K) and estradiol (F and P) were measured at the indicated time points in SARS-CoV-2-infected or control-treated (PBS, Poly(I:C)) male (A and F) and female (K and P) hamsters (n = 5; day 3 p.i., n = 5–10).

(B, C, G, H, L, M, Q, and R) Androgen receptor (AR) (B and L), zinc transporter 9 (ZIP-9) (C and M), estrogen receptor α (ESR-α) (G and Q), and estrogen receptor β (ESR-β) (H and R) mRNA expression in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected and control-treated (PBS, Poly(I:C)) male (B, C, G, H) and female (L, M, Q, R) hamsters at day 3 p.i. (n = 5; Poly(I:C), n = 4–5).

(D, E, I, J, N, O, S, and T) AR (D and N), ZIP-9 (E and O), ESR-α (I and S), and ESR-β (J and T) mRNA expression in lung macrophages isolated from uninfected male (D, E, I, J) and female (N, O, S, T) hamsters (n = 8–11) upon ex vivo PBS or Poly(I:C) treatment.

In (B–E), (G–J), (L–O), and (Q–T), relative hormone receptor mRNA expression values in PBS-treated controls were set to 1. Values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA or paired Student’s t test (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

In infected female hamsters no significant alteration in plasma testosterone levels was detected, in line with the physiologically very low levels of testosterone in young female hamsters as expected (Figure 4K). High virus titers were detected on day 3 p.i. in females, comparable to the virus dynamics detected in males. No alterations in the expression of the androgen receptors AR and ZIP-9 were detected (Figures 4L–4O). Estradiol levels, however, were reduced in SARS-CoV-2-infected female hamsters by 5-fold compared to the respective PBS control group (Figure 4P). Virus titers were negatively associated with estradiol levels in infected female hamsters on day 3 p.i. Estrogen receptor ESR-α expression was reduced in SARS-CoV-2-infected female lungs, while ESR-β expression levels were not affected (Figures 4Q and 4R). In poly(I:C)-treated lung macrophages, ESR-α expression was slightly reduced and ESR-β expression strongly reduced (Figures 4S and 4T).

These findings support the concept that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes dysregulated sex hormone levels in the plasma and ESR-β expression patterns in the lung of male hamsters.

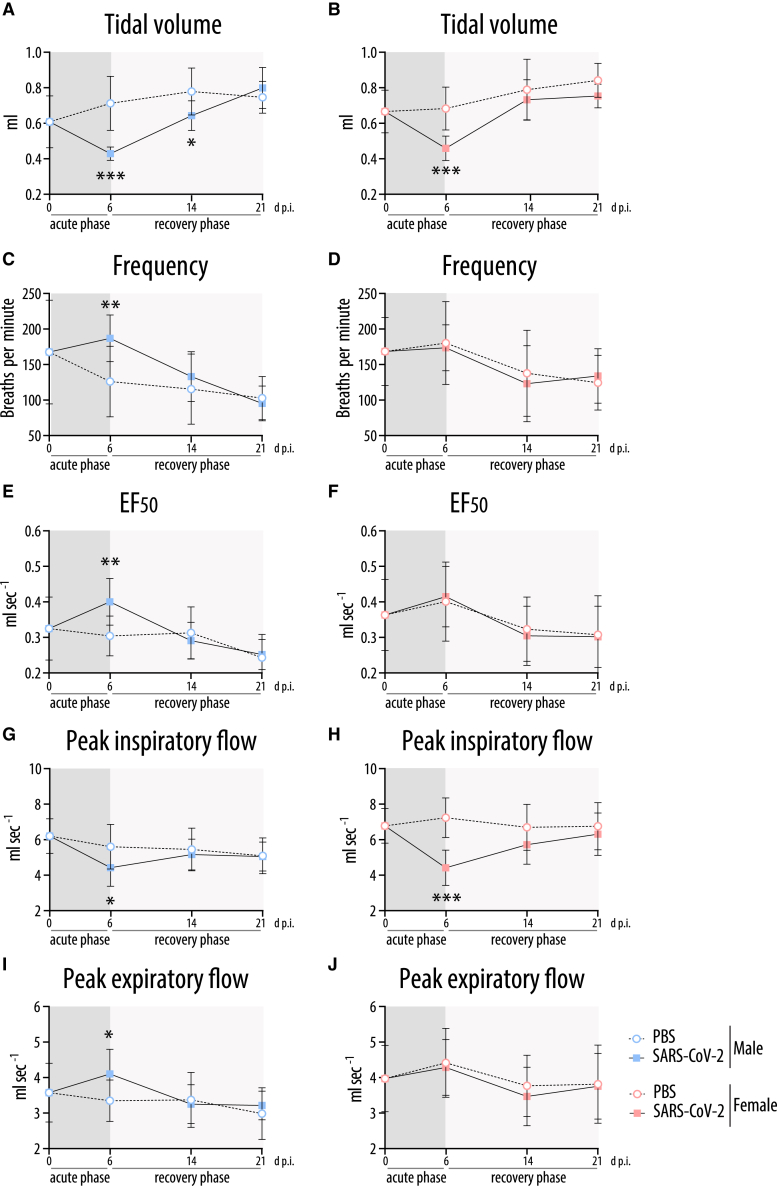

Dysregulated sex hormone metabolism is associated with prolonged respiratory dysfunction in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

Sex hormones were repeatedly shown to affect lung health.19,20,21,22,23 Thus, we next measured respiratory function longitudinally in SARS-CoV-2-infected male and female hamsters (Figures 5 and S6).

Figure 5.

Lung plethysmography in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters

Whole-body plethysmography in SARS-CoV-2-infected or control (PBS)-treated male (A, C, E, G, I) and female (B, D, F, H, J) hamsters at the indicated time points (n = 10; day 0 p.i., n = 12): tidal volume (A, B), frequency (C, D), EF50 (expiratory flow rate at the point 50% of tidal volume is expired) (E, F), peak inspiratory flow (G, H), and peak expiratory flow (I, J). Values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired Student's t test (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Respiratory function was more severely impaired in infected males compared to females on day 6 p.i. In both sexes, the tidal volume was reduced on day 6.p.i., which persisted in males until day 14 p.i. (Figures 5A and 5B). Male hamsters compensated this deficit by a higher breathing frequency, resulting in a normal ventilation rate (Figures 5A, 5C, and S6A). In contrast, the breathing frequency remained normal in females that showed a similarly reduced tidal volume as males at the cost of a slightly reduced ventilation rate (Figures 5B, 5D, and S6B). In line with restrictive lung disease, the expiratory flow was enhanced in male hamsters while their inspiratory flow was reduced (Figures 5E, 5G, and 5I). These changes remained visible in part until day 14 p.i. (Figures 5 and S6). Again, infected female hamsters had a normal expiratory flow with a reduction in inspiratory flow only (Figures 5F, 5H, and 5J). Inspiratory and expiratory pauses were shortened in both males and females (Figures S6C–S6F).

Taken together, the results of the comprehensive lung function tests show that SARS-CoV-2-infected female hamsters recover on day 14 p.i. In contrast, infected male hamsters still present an impaired respiratory capacity on day 14 p.i. accompanied by local fibrotic structures (Figure S7).

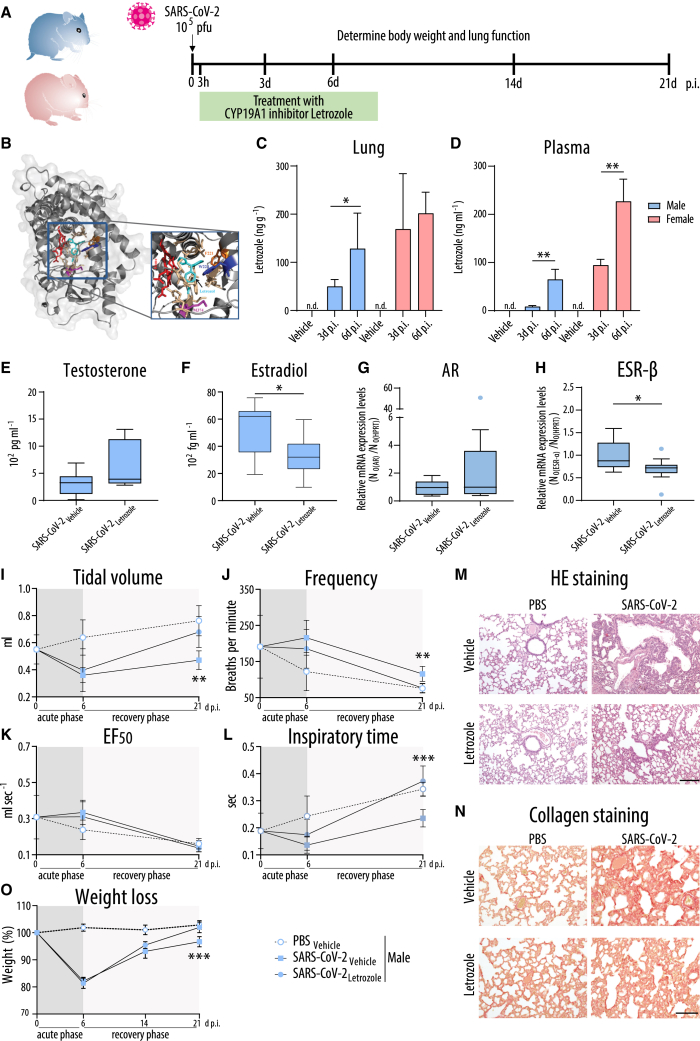

CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole improves lung health in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

Next, we sought to understand whether CYP19A1 acts causally on overall lung health. First, we treated human lung cells (Calu-3) with testosterone in presence or absence of the clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole, followed by infection with SARS-CoV-2 before finally measuring estradiol in the supernatant. Thereby, we confirmed an increase in estradiol levels in the cell supernatant after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Letrozole treatment was able to reverse this effect by significantly reducing estradiol levels in the supernatant (Figure S8). These findings support the hypothesis that CYP19A1 expression in the lung is able to convert testosterone to estradiol in a defined setting, which can be inhibited by letrozole.

Therefore, we next treated SARS-CoV-2-infected male and female hamsters with letrozole (Figures 6A and 6B). Oral letrozole treatment is used in humans for the treatment of estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer in women42 as well as to treat hypogonadism in men.43

Figure 6.

Treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters with the CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole

(A) Timeline of experimental setup for letrozole treatment. Male and female hamsters were control treated with PBS or infected with SARS-CoV-2 and subjected to daily letrozole treatment from 3 h to 8 days p.i.

(B) Docking model of CYP19A1-letrozole complex adapted from Hong et al.44

(C and D) Letrozole levels in lung (C) and plasma (D) of male and female hamsters treated with vehicle or letrozole. n.d., not detectable.

(E–H) Testosterone (E), estradiol (F), as well as lung AR (G) and ESR-β (H) mRNA expression at 3 days p.i. (E, F) or 6 days p.i. (G, H) (n = 11). (G and H) SARS-CoV-2-infected and vehicle-treated hamsters were set as 1. Data are shown as a box-and-whisker plot.

(I–L) Whole-body plethysmography in infected male hamsters: Tidal volume (I), frequency (J), EF50 (K), and inspiratory time (L) (n = 5–7; day 0 p.i., n = 12).

(M and N) H&E staining (M) or collagen staining with Sirius red (N) of lung sections from infected male hamsters at 21 days p.i. (n = 5–7 per group). Scale bars, 200 μm (M) and 100 μm (N).

(O) Weight loss of infected male hamsters (n = 5–7 per group).

In (C), (D), (I–L), and (O), values are shown as means; error bars are shown as SD. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney test or one-way ANOVA (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, we confirmed that the applied oral treatment regimen results in comparable doses in the lungs of male and female animals (Figure 6C). While in the male and female lungs letrozole was detected to comparable levels on days 3 and 6 p.i., plasma levels of letrozole were higher in infected females compared to males on days 3 and 6 p.i. (Figure 6D), supporting sex-dependent pharmacokinetics for letrozole that was also reported previously.45,46,47

Letrozole treatment resulted in elevated testosterone levels in virus-infected males, albeit not to a statistically significant extent (Figure 6E). Estradiol levels were significantly reduced upon letrozole treatment in infected males (Figure 6F). Letrozole treatment resulted in a trend toward elevated AR transcription in the lungs of infected males (Figure 6G). However, ESR-β transcription levels were significantly reduced in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters upon letrozole treatment (Figure 6H). No significant changes were detected in ZIP-9 and ESR-α expression levels in infected males upon letrozole treatment (Figures S9A and S9B). In females, letrozole treatment led to significantly increased testosterone levels and a tendency toward reduced estradiol levels (Figures S9C and S9D). None of the androgen or estrogen receptor expression levels were affected in the lungs of infected females upon letrozole treatment (Figures S9E–S9H).

We then assessed whether recovered sex hormone levels might result in improved lung function in SARS-CoV-2-infected males and females. In PBS male and female controls, treatment with letrozole or vehicle did not affect lung function, ruling out an adverse effect in this regard (Figures S10 and S11). In males infected with SARS-CoV-2, letrozole treatment resulted in faster recovery of the tidal volume from day 6 p.i. onward, ultimately attaining the level of the vehicle group. Accordingly, the breathing frequency showed accelerated normalization in letrozole-treated animals, resulting in a longer inspiratory time (Figures 6I–6L and S12). This correlated histologically with fewer collapsed alveoli, fewer immune cell infiltrates in adjacent alveolar spaces, and less alveolar wall thickening in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected males upon letrozole treatment (Figure 6M). In line with this, letrozole-treated males presented fewer fibrotic structures on day 21 p.i. compared to vehicle-treated males (Figure 6N). Overall, these findings were reflected by an increased weight gain of letrozole-treated males compared to vehicle males on day 21 p.i. (Figure 6O). In contrast, letrozole treatment did not improve lung function in SARS-CoV-2-infected females at any time point (Figures S9 and S12). In line with this, neither lung pathology nor weight was significantly improved in letrozole-treated infected females as compared to vehicle controls (Figures S9M–S9O).

These findings show that treatment with the clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole substantially improves male lung health in the hamster model.

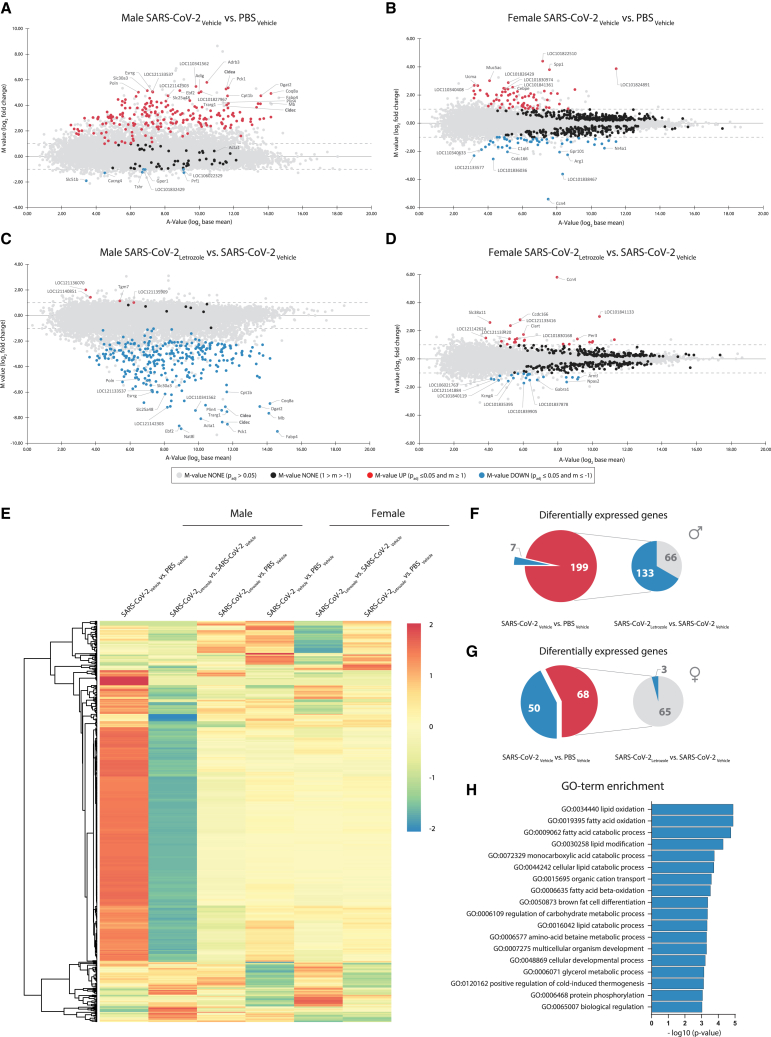

Whole-lung transcriptome analysis identifies letrozole-treatment-modified pathways associated with improved lung health in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters

To investigate which pathways might be modulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected male lungs that impair full recovery and how letrozole treatment contributes to improved lung health, we performed whole-lung transcriptomic profiling on day 21 p.i. To this end, we compared male and female hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 and treated them with either letrozole or vehicle. As negative controls, we included males and females inoculated with PBS and then treated with letrozole or vehicle. A total of 120 million sequence reads (on average approximately 4 million reads for each of five replicates per condition) amounting to 103 Gb sequence information were generated for all transcriptome libraries. Quality filtering resulted in high-quality sequence reads that were mapped onto the Syrian hamster draft genome sequence. For all conditions, the amount of mapped hamster reads was about 92% of all reads. We found that differential genes were expressed in males and females infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 7A and 7B). Interestingly, the transcriptomic profile significantly changed in the infected male lungs treated with letrozole (Figure 7C) in contrast to letrozole-treated infected females (Figure 7D). In SARS-CoV-2-infected males and females, a total of 256 genes were upregulated, 188 of which were male specific and 57 female specific, with another 11 shared by both sexes (Figures 7A–7E). A total of 56 genes were downregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected animals with 6 being male specific, 49 female specific, and 1 common gene. Letrozole treatment resulted in the downregulation of 133 out of 199 upregulated genes in infected males (Figure 7F). In contrast, in letrozole-treated infected females, 65 out of 68 genes remained unaltered (Figure 7G). Thus, letrozole treatment results in sex-specific alterations in the transcriptomic profile of the lung. Here, improved lung health in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters upon letrozole treatment was associated with changes in many pathways, among which those involved in lipid and protein processes, e.g., lipid oxidation (gene ontology term GO:0034440), lipid modification (GO:0030258), and protein phosphorylation (GO:0006468) were among the most significant (Figure 7H).

Figure 7.

Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamster lungs treated with the CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole

(A–D) Genome-wide lung transcriptomic profiles of PBS-control-treated or SARS-CoV-2-infected male (A and C) and female (B and D) hamsters (n = 5), treated with vehicle or letrozole, at 21days p.i. were compared and are shown as ratio/intensity scatterplots (M/A plot [M-value = log2 fold change; A-value = log2 base mean]).

(E) Heatmap depicting normalized expression of differentially expressed genes in the lung of male and female hamsters, clustered according to their expression profiles (cutoff log2 fold change ≥1 or ≤−1, with an adjusted p value of ≤0.05).

(F and G) Significant differentially expressed genes in the lung of control (PBS) or SARS-CoV-2-infected male (F) and female (G) hamsters.

(H) Gene ontology term enrichment (biological process) of genes that were significantly downregulated in letrozole-treated SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters, compared to the vehicle control group.

These data show that letrozole treatment can recover most of the dysregulated genes in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected males but not females.

Discussion

We herein identified the CYP19A1 gene as a crucial factor contributing to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in males by analyzing WES data derived from 2,866 COVID-19 patients and autopsy-derived lung tissues from 86 COVID-19 decedents. Men with a CYP19A1-activity-increasing mutation (Thr201Met)30 were more likely to be hospitalized with severe COVID-19 compared to men who did not possess this mutation or compared to women with COVID-19. Moreover, we found that elevated CYP19A1 expression was still prominent in the lungs of male COVID-19 patients at the time of death, when in most cases viral RNA was no longer detectable.

Using the golden hamster model, we studied in depth a putative causal role of CYP19A1 in sex-dependent disease outcome. We identified a causal role of CYP19A1 in male SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in hamsters.

Male and female hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 presented comparable weight loss until day 6 p.i. (the acute phase of infection) but showed significant differences from day 7 until 14 p.i. (recovery phase). SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters presented delayed weight gain and impaired lung function even 1 week after recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Impaired male lung health correlated with altered gene expression profiles in the male lung and its macrophages, such as increased CYP19A1 expression and elevated ESR-β expression, which were further associated with reduced plasma testosterone and elevated plasma estradiol levels. Interestingly, we could also detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA and/or replicating virus in the testes and brain of male hamsters, but expression levels of CYP19A1 were generally not affected or even reduced in some cases (Figures S13 and S14). Thus, altered circulating sex hormone levels correlate mainly with increased CYP19A1 expression levels in the lungs of male hamsters upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, viral replication in the testes suggests a potential gonadal hit that likely additionally contributes to overall reduced testosterone levels. Alterations in circulating sex hormone levels detected in male hamsters are in agreement with reduced testosterone and elevated estradiol levels in the plasma of men hospitalized with COVID-19.11,12,13 Follow-up studies in men show that even 1 year after initial SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, 30% of COVID-19 patients still present testosterone levels that are below clinical references.15

In female hamsters, we found that respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection also causes reduced lung function, albeit to a lesser extent when compared to males. SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces plasma estradiol levels in females, which might be explained by viral replication in the ovaries independently of CYP19A1 expression (Figure S13). Similar to infected male hamsters, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the brain without affecting CYP19A1 expression (Figure S14). Most critically ill female COVID-19 patients, however, were post-menopausal,13 which limits the translation of the data obtained in the young female animals at reproductive age used in this study. However, our findings here, where disease onset in females infected with SARS-CoV-2 correlate with low estradiol levels (in contrast to high estradiol levels in males), would be in line with the generally low estradiol levels in post-menopausal women. Nevertheless, future investigations are needed to understand the role of sex hormones on COVID-19 outcome in pre- compared to post-menopausal women.

Interestingly, low testosterone levels were previously reported to pose a poor prognostic marker in male but not female patients with avian H7N9 influenza A virus infection.48 However, in contrast to COVID-19, avian H7N9 influenza was not paralleled by significantly elevated estradiol levels suggestive of common but also distinct mechanisms contributing to sex-dependent disease outcome upon respiratory virus infection.

The causal role of CYP19A1 in male SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and male lung health was underpinned by treating infected hamsters with the clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole. SARS-CoV-2-infected male and female hamsters treated with letrozole showed elevated circulating testosterone levels and reduced circulating estradiol levels suggestive of functional CYP19A1 inhibition in both sexes. In males, full recovery of testosterone levels (in contrast to estradiol levels) could not be achieved. One possible reason for this could be the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the testis of infected males that likely contributes to impaired testosterone synthesis without the involvement of CYP19A1. However, reducing circulating estradiol levels as well as ESR-β expression in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected males by letrozole treatment resulted in improved lung health with overall faster recovery in males. Thus, letrozole-treated males showed improved lung function that was reflected by ameliorated lung pathology and accelerated weight gain after virus clearance. In contrast, letrozole treatment did not show any benefit for SARS-CoV-2-infected females. These findings further confirm a causal role for CYP19A1 in male SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis.

While these findings might suggest that replacement of testosterone levels could provide an additional treatment option, this should be considered with caution. One reason for this is that CYP19A1 transcription is likely dependent on testosterone concentration due to the presence of an AR binding site in its promoter region. Indeed, testosterone-dependent CYP19A1 expression was confirmed in the lungs of male hamsters treated with testosterone (Figures S15A and S15B). Low-dose testosterone treatment increased CYP19A1 mRNA expression in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters, while high-dose testosterone treatment inhibited CYP19A1 expression in the lungs of infected animals to physiological levels as in uninfected PBS-treated males (Figure S15B). Low-dose testosterone treatment associated with high CYP19A1 expression caused slightly elevated lung frequency, elevated ESR-β expression, increased weight loss, and reduced survival (Figures S15C–S15F). In contrast, high-dose testosterone treatment associated with inhibited CYP19A1 expression resulted in reduced lung frequency, reduced ESR-β expression, weight loss, and increased survival compared to low-dose testosterone treatment in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters (Figures S15C–S15F). These findings highlight the complexity of testosterone treatment in infected animals, which could be beneficial or detrimental depending on the dosage used. However, the detection of testosterone-dependent CYP19A1 expression sheds new light on our current understanding, further highlighting the promising role of CYP19A1-targeted therapy that aims to balance sex hormone levels rather than substituting one hormone alone.

Mechanistically, whole-lung transcriptome analysis of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters with letrozole or vehicle treatment revealed key pathways associated with improved male outcome. We identified a series of gene pathways in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected males upon letrozole treatment as compared to vehicle controls. The major pathways that were differentially altered upon letrozole treatment were involved in lipid oxidation, lipid modification, and protein phosphorylation. The prominent involvement of lipid pathways is interesting given that there is evidence that efficient SARS-CoV-2 replication depends on lipid metabolism.49 Alveolar lipids are known to be involved in pulmonary diseases.50 Similarly, for both sex steroids their involvement in wound healing has been reported previously.51 It was reported that ovariectomized rats present diminished fibrosis, while estradiol replacement restored fibrotic response.52 In mice, testosterone treatment restored asthmatic lung exacerbation by attenuating airway inflammation.53 Population-based studies further supported this concept by showing strong associations between testosterone levels and lung function in men.54 Although future studies are required to understand in more detail androgen- and/or estrogen-controlled transcription pathways involved in long-term lung health, our data further support the concept that balanced sex hormone levels are critical for lung health in general (Figure S16).

Besides fixing genetic variations in the CYP19A1 gene, sex hormone levels can be additionally affected by other dynamic conditions such as age or metabolic comorbidities. Testosterone is produced in the gonads of boys at the age of 10–12 years, peaking in adulthood and steadily declining with increasing age. Age-related testosterone deficiency due to testicular dysfunction (primary hypogonadism) may thus pose another risk factor for reduced lung health as was previously reported in population-based studies.54 Obesity is another high-risk factor for severe and even fatal COVID-19 outcome. CYP19A1 is highly expressed in adipose tissue, where it also converts testosterone to estradiol. In obese people, low testosterone and elevated estradiol levels have been reported previously.43,55,56

Thus, we propose that the combination of a fixed genetic CYP19A1 hit (Thr201Met) with several dynamic CYP19A1 hits (SARS-CoV-2-infection-induced elevated CYP19A1 transcription in the lung, age-related hypogonadism, and obesity) may orchestrate a deadly quartet in COVID-19 males.

Letrozole is a CYP19A1 inhibitor that is widely and successfully used in treating hypogonadism in men and estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer in women. Letrozole was reported to inhibit wild-type as well as the Thr201Met variant of the CYP19A1 protein equally as effectively.30 This suggests that men carrying a heterozygous or homozygous Thr201Met variant would be expected to benefit from letrozole treatment. Letrozole treatment was furthermore shown to normalize serum testosterone levels in obese men with hypogonadism.43 Thus, beyond the direct effect of letrozole on inhibiting the SARS-CoV-2-infection-induced upregulation of CYP19A1 and thereby sex hormone dysregulation, patients with additional sex hormone balance-disturbing conditions (CYP19A1 Thr201Met, age, and obesity) might additionally benefit from letrozole treatment upon SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Collectively, these findings highlight that the CYP19A1 gene is involved in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in males. We identified the clinically approved CYP19A1 inhibitor letrozole as a potential new therapeutic strategy to improve long-term disease outcomes in SARS-CoV-2-infected males.

Limitations of the study

This study has limitations that should be considered. The human genome data identified the CYP19A1-activity-increasing variant Thr201Met as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 in male patients. However, sex hormone levels were not measured within this patient cohort. Thus, future studies are needed that measure sex hormone levels in patients harboring the CYP19A1-activity-increasing variant Thr201Met in comparison to other variants with unaffected CYP19A1 activity, preferably before and after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Another limitation of the study is that the positive treatment outcome with letrozole in SARS-CoV-2-infected male hamsters cannot be extrapolated to humans. Future investigations are required to evaluate letrozole therapy in COVID-19 patients while taking the complexity of hormonal mode of action into account.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Aromatase (CYP19A1) | Abcam | Cat# ab18995; RRID:AB_444718 |

| Monoclonal mouse antibody anti-SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid | Synaptic Systems | Cat# HS-452 011; RRID:AB_2891261 |

| Rabbit Anti-CD31 | Acris Antibodies | Cat# AP15436PU-N; RRID:AB_1927004 |

| Anti-CD204, MSR1 monoclonal antibody clone SRA-E5 | Abnova Corporation | Cat# MAB1710; RRID:AB_ 1678864 |

| Von Willebrand Factor VIII | Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions | Cat# A0082; RRID: AB_2315602 |

| Monoclonal antibodies anti-Smooth Muscle Actin | Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions | Cat# M0851; RRID: AB_2313736 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-CD3 | Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions | Cat# A0452; RRID: AB_2335677 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid antibody | Sino Biological | Cat# 40143-MM05; RRID: AB_2827977 |

| Anti-mouse CD68 antibody clone: FA-11 | BioLegend | Cat# 137002; RRID:AB_2044004 |

| Purified Rat Anti-Mouse CD16/CD32 (Mouse BD Fc Block™) Clone 2.4G2 | BD Bioscience | Cat# 553141; RRID:AB_394656 |

| Virus strains | ||

| SARS-CoV-2/Germany/Hamburg/01/2020 | Isolated from patients; this paper | ENA study PRJEB41216, sample ERS5312751 |

| SARS-CoV (Frankfurt 1) | Institute of Virology Charité, Berlin, Germany | N/A |

| A/Hamburg/NY1580/09 (H1N1) | Isolated from patients; Otte et al.57 | https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00665-15 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Lung tissue samples of deceased COVID-19 patients | University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Mendeley Data | Table S1https://doi.org/10.17632/4xytrnhx76.1 |

| Lung tissue samples of deceased COVID-19 patients | University Hospital Tübingen, Mendeley Data | Table S1https://doi.org/10.17632/4xytrnhx76.1 |

| Lung tissue samples of deceased COVID-19 patients | Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam, Mendeley Data | Table S1https://doi.org/10.17632/4xytrnhx76.1 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Letrozole | Sigma-Aldrich GmbH | Cat# L6545 |

| Testosterone enanthate | LGC Standards GmbH | MM1119.00–0250 |

| True Nuclear Transcription Buffer Set | BioLegend | Cat# 424401 |

| Desoxyribonuklease (Dnase I) | STEMCELL | Cat# 07470 |

| Poly(I:C) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P9582 |

| Collagenase type 1 (C0130) | STEMCELL | Cat# 07416 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| RealStar® SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Kit RUO | Altona Diagnostics | Cat# 821005 |

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 52904 |

| InnuPREP RNA Mini Kit 2.0 | IST Innuscreen | 845-KS-2040250 |

| Multi-Species Hormone Magnetic Bead Panel | Merck | Cat# MSHMAG-21K |

| Estradiol ELISA | Calbiotech | Cat# ES380S Cat# ES180S-100 |

| DetectX® Testosterone ELISA Kit | Arbor Assay | Cat# AAY-K032-H |

| DetectX® 17β-Estradiol ELISA Kit | Arbor Assay | Cat# AAY-K030-H |

| RNAscope™ Probe- V-nCoV2019-S-sense | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat# 845701 |

| RNAscope 2.5 HD Detection Kit | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat# 322350 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Genome-wide transcriptomic data of the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters | This paper | EBI ArrayExpress server: E-MTAB-13100 |

| Demographic information of deceased COVID-19 patients and controls | This paper | Table S1https://doi.org/10.17632/4xytrnhx76.1 |

| Overview of RNAseq data | This paper | Table S2https://doi.org/10.17632/4w5z7crgsv.1 |

| Gene ontology term enrichment for biological processes | This paper | Table S3https://doi.org/10.17632/4y3h9kp4y8.1 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| MDCK II | ATCC | Cat# CRL-2936, RRID:CVCL_B034 |

| VeroE6 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-81, RRID:CVCL_0059 |

| Calu-3 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-55 |

| CaCo-2 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-37 RRID:CVCL_0025 |

| A-498 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-44 RRID:CVCL_1056 |

| Huh-7 | Prof. Dr.Thomas Dobner, Leibniz Institute of Virology, Hamburg, Germany | N/A |

| DAOY | ATCC | Cat# HTB-186 RRID:CVCL_1167 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Syrian golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus), RjHan:AURA | Janvier Labs | Cat# HAMST |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Oligonucleotides sequences | This paper; Mendeley Data | Table S4https://doi.org/10.17632/8yr83bz9b3.1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | Dotmatics | Version 9.0.1 |

| MyAssays | MyAssays | MyAssays Ltd 2021 |

| FinePointe Software System | Data Sciences International | FinePointe v2.9.0 |

| LightCycler® 96 Software | Roche | Version v1.1.0.1320 |

| LinReg PCR Software | Ruijter et al.58 |

https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp045; Version v2018.0 |

| Visiopharm Software | Visiopharm, Hørsholm, Denmark | N/A |

| Data analysis of cDNA libraries | Described in Wibberg et al.59 | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2561-1 |

| GOrilla | Eden et al.60 | https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-48 |

| Other | ||

| Syrian golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) whole genome | NCBI | RefSeq: JAFVMI010000001 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources, data and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Prof. Dr. Guelsah Gabriel (guelsah.gabriel@leibniz-liv.de).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact Prof. Dr. Guelsah Gabriel with a completed material transfer agreement.

Experimental model and study participant details

GEN-COVID cohort

The post-Mendelian model uses an integrated polygenic score (IPGS) to predict COVID-19 disease severity. The model was previously trained over the GEN-COVID cohort and validated using several independent COVID-19 cohorts.27,28,29 Briefly, the IPGS used to predict COVID-19 severity is a weighted average of selected features representing whole exome sequencing (WES) data in a binary format. Feature selection is performed using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) over a series of logistic models trained to predict a phenotype of COVID-19 severity adjusted by age and gender (male or female was defined as self or physician reporting). Patients of the GEN-COVID cohort were first graded using the modified version of WHO COVID-19 Outcome Scale used for severity grading, as follows: 5. death; 4. hospitalized receiving invasive mechanical ventilation; 3. hospitalized, receiving continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) ventilation; 2. hospitalized, receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen; 1. hospitalized, not receiving supplemental oxygen; and 0. not hospitalized.61 Then, two Ordered Logistic Regression (OLR) models were fitted using age to predict the ordinal grading (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) dependent variable, separately for male and female cohorts. In this way, it was possible to assign to each patient clinical classification equal to 0 (milder), if the actual patient grading was below the one predicted by the OLR; or equal to 1 (more severe), if the grading was above the OLR prediction. The patients with a predicted grading equal to the actual grading were excluded from the following analyses in order to compare patients where the genetic contribution toward the more severe/milder phenotype is expected to be more relevant. In order to evaluate the significance of the association between Thr201Met CYP19A1 variant and COVID-19 severity, the Chi-Square Test was used.

Fatal COVID-19 cases and controls

Autopsy-derived lung material from male and female patients, who died of COVID-19, were obtained from three independent study sites: Hamburg, Tübingen and Rotterdam. Lung biopsies from patients how were tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in qRT-PCR were used as controls. For all deceased patients at the University Hospital Tübingen, ethical approval had been obtained from the next of kin (097/2021BO2).62

Cells

Calu-3 (ATCC HTB-55), Huh-7 (kindly provided by Thomas Dobner, Leibniz Institute of Virology, Hamburg, Germany), CaCo-2 (ATCC HTB-37), A-498 (ATCC HTB-44) and DAOY cells (ATCC HTB-186) were cultured in the manufacturer’s recommended medium.

Animals

Male and female golden hamsters (8–12 weeks old) were purchased from Janvier. All animals were kept under standard housing conditions (21 ± 2°C, 40–50% humidity, food and water ad libitum) with a 12:12 light–dark cycle at the Leibniz Institute of Virology in Hamburg, Germany.

Method details

Viruses

The SARS-CoV-2 strain (SARS-CoV-2/Germany/Hamburg/01/2020; ENA study PRJEB41216 and sample ERS5312751) was isolated from COVID-19 patient material. Briefly, VeroE6 cells were inoculated with 200 μL of a human nasopharyngeal swab of a confirmed patient with COVID-19 in Hamburg and propagated for three serial passages in VeroE6 cells. The SARS-CoV (Frankfurt 1) was also grown and titrated in VeroE6 cells. VeroE6 were cultivated in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine at 37°C for virus propagation. The 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus (A/Hamburg/NY1580/09; H1N1)57 was grown and titrated in MDCK II cells. MDCK II cells were cultivated in MEM (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine and 1 μg ml−1 L-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) at 37°C. All cells were tested negative for Mycoplasma sp. by PCR. All infection experiments with SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were performed in the biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory at the Leibniz Institute of Virology in Hamburg, Germany.

Animal experiments

For SARS-CoV-2 infection, male and female hamsters were anesthetized with 150 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg kg−1 xylazine by intraperitoneal injection. The animals were intranasally inoculated with 105 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.) SARS-CoV-2, mock infected with PBS or were administered with 1 mg kg−1 poly(I:C). Letrozole dosing was calculated for male and female hamsters by taking sex-specific half times into consideration as reported before.45,46,47,63,64 For letrozole treatment, male and female hamsters received a final dose of 0.36 mg kg−1 d−1 or 0.18 mg kg−1 d−1 letrozole, respectively, (dissolved in DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) diluted in sterile saline (Braun), respectively, by oral gavage (stainless-steel gavaging needles) at 3 h and day 1–3 post infection (p.i.). As control, hamsters were treated by oral gavage with DMSO as vehicle. To reduce stress induced by oral gavaging according to animal welfare regulations, after day 4 p.i. until day 8 p.i., hamsters were offered letrozole or DMSO as a vehicle control via water gel packages (Necta) supplemented with 1% glucose and a final concentration of 0.0018 mg mL-1 or 0.0036 mg mL−1 letrozole for female and male hamsters, respectively. For testosterone treatment, male hamsters received 1 mg kg−1 or 10 mg kg−1 testosterone enanthate (dissolved in sesame oil) by subcutaneous injection at 3 h and 3 days p.i. As control, PBS-treated or infected male hamsters were treated subcutaneously with sesame oil as vehicle.

Body weight was monitored daily up to 14 or 21 days post infection (d p.i.). On day 1, 3, 6, 14 or 21 p.i., five to ten animals per group were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of pentobarbital (800 mg/kg). Blood was drawn by cardiac puncture and collected in EDTA tubes. Blood was centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 g and 4°C, and the plasma was stored at −80°C. Lungs, brains and gonads were homogenized in 1x PBS and supernatants were stored at −80°C. For histopathological examination, lungs, brains and gonads were fixed by immersion in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. For total RNA isolation, lungs, brains and gonads were incubated in RNAprotect Tissue Reagent (QIAGEN), for at least 24 h at 4°C and stored at −80°C.

All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines of German animal protection law and were approved by the relevant German authority (Behörde für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz; protocols N 032/2020, N 103/2020 and N 108/2022).

Histology and immunohistochemistry in fatal COVID-19 cases

For immunohistochemical detection of CYP19A1 in the lungs of deceased male and female COVID-19 patient's tissue probes were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Demographic information of deceased COVID-19 patients and controls are listed in Table S1, available at Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/4xytrnhx76.1.

For immunohistochemistry at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, sections were cut at 2 μm. After dewaxing and inactivation of endogenous peroxidases (PBS/3% hydrogen peroxide), antibody specific antigen retrieval was performed using the Ventana Benchmark XT machine (Ventana, Tuscon, Arizona, USA). Sections were incubated with anti-CYP19A1 (1:400) or anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein antibody (1:2,000). For detection of specific binding, the Ultra View Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana, Roche) was used, which contains secondary antibodies, DAB stain and counter staining reagent for detection of nuclei. Staining were evaluated by an experience pathologist and representative images were taken with a Leica DMD108 digital microscope.

For immunohistochemistry at the University Hospital Tübingen, immunohistochemical analysis was performed by using the polyclonal antibody directed against CYP19A1 (1:400) on an automated immunostainer following the manufacturer’s protocol (Benchmark; Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) and using the ultraView detection system (Ventana) and diaminobenzidine as substrate.

For immunohistochemistry at the Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam, immunohistochemistry was performed with an automated, validated and accredited staining system (Ventana, Tuscon, Arizona, USA) using optiview universal DAB detection Kit. In brief, following deparaffinization and heat-induced antigen retrieval for 32 min with CC1 the tissue samples were incubated with rabbit-anti-human CYP19A1 (1:400) for 32 min. Incubation was followed by hematoxylin II counter stain for 12 min and then a blue coloring reagent for 8 min according to the manufactures instructions (Ventana, Tuscon, Arizona, USA).

In situ hybridization (ISH)

To detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA, lung tissue sections were hybridized using specific probes for SARS-CoV-2 (ACD, Newark, CA, USA) followed by the RNAscope 2.5 HD Detection Kit Red from ACD (Newark, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Plethysmography

Respiratory function was assessed using an unrestrained barometric whole-body plethysmography. In brief, Syrian golden hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 or mock infected with PBS were placed in a sealed cylindrical Buxco WBP chamber (Rat WBP standard chamber) on day 0, 6, 14 and/or 21 p.i., and changes in pressure caused by tidal breathing movements were measured using a volumetric flow transducer (FP WBP Flow Transducer w/T&HF, Data Sciences International) and amplified. Flow fluctuations were recorded using FinePointe Software System (v2.9.0, Data Sciences International). At the beginning of each session, the plethysmograph was calibrated. Several parameters were obtained, including breath frequency (breaths/min), tidal volume (Ti, ml), expiratory flow rate at the point 50% of tidal volume is expired (EF50, ml/s), peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFb, ml/s), peak expiratory flow rate (PEFb, ml/s), minute volume (mL/min), end inspiratory pause (EIP, ms), end expiratory pause (EEP, ms), inspiratory time (Ti, sec) and expiratory time (Te, sec). Measurements were performed for 10 min, after 20 min (females) or 30 min (males) acclimatization periods.

Histology and immunohistochemistry in hamsters

Tissues were routinely embedded in paraffin and evaluated via light microscopy of hematoxylin and eosin (HE) as well as Azan stained slides.

Immunohistochemical detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (NP), CYP19A1, cluster of differentiation (CD) 204, von-Willebrandt-factor (vWF), CD31, CD3 and smooth muscle actin (SMA) in the golden hamster lungs was performed using the EnVision+ System (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions). Serial sections of tissue were dewaxed and rehydrated in isopropanol and 96% ethanol followed by blockage of endogenous peroxidase by incubation in 85% ethanol with 0.5% H2O2 for 30 min at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubation in citrate (10 mM citric acid, 0.05% Tween 20) or citrate-Na2H2EDTA buffer (10 mM citric acid, 2 mM Na2H2EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20) for 20 min in a microwave at 800 W, followed by 20 min at room temperature. Sections were afterward transferred to Shandon Coverplates (Thermo Electron GmbH) and stained with either polyclonal antibodies directed against CYP19A1 (1:500), CD31 (Acris, 1:100), CD204 (Abnova Corporation, 1:500) and vWF (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions, 1:500) or monoclonal antibodies against SMA (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions, 1:100), CD3 (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions, 1:100) and SARS-CoV-2 NP (Sino Biological, 1:32,000) over night at 4°C. Antibodies were diluted in 1x PBS containing 1% BSA and addition of 0.3% Triton X-100 for the CYP19A1, SMA and SARS-CoV-2 NP stainings. Sections were subsequently rinsed, and the peroxidase-labeled polymer was applied as secondary antibody for 30 min. Visualization of the reaction was accomplished by incubation in chromogen 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, 0.05%) and 0.03% H2O2 in 1x PBS for 5 min and afterward counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin for 1 min. For negative controls, the primary antibody was replaced by either rabbit normal serum (1:3,000) or ascites fluid from Balb/c mice (1:1,000). The serial stainings were afterward analyzed by light microscopy.

For the detection of collagen, picro sirius red stain kit (PSR-1-IFU, Sky tekLogan, Utah, USA) was used according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

For the quantification of Azan positive collagen fiber content in the lungs and CYP19A1 expressing tissue in lungs and gonads, slides were digitized using the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S210 (Hamamatsu Photonics, Herrsching am Ammersee, Germany) slide scanner. Image analysis was performed on the whole-slide images. Initially lung tissue was detected using a specifically trained Bayesian classifier followed by DAB positive and negative (tissue) pixel count for CYP19A1 staining or Azan positive and negative pixel count for collagen detection using the Visiopharm Software (Visiopharm, Hørsholm, Denmark). Percentage of CYP19A1 positive tissue and Azan positive collagen fiber content was calculated for each lung section present on a slide individually and a median expression value was calculated for each animal.

Determination of virus titers and viral RNA levels

Homogenization of organs was performed in 1 mL 1x PBS with 5 sterile, stainless steel beads (Ø 2 mm, Retsch) at 30 Hz for 10 min in the mixer mill MM400 (Retsch).

For determination of the virus titer, tissue homogenates and cell culture supernatants were titrated for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 on VeroE6 cells and for H1N1 on MDCK cells in 10-fold serial dilutions for 30 min at 37°C and overlaid with MEM (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) supplemented with 0.2% BSA, 1% L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1.25% Avicel and 1 μg mL−1 Trypsin-TPCK (only for H1N1). After 72 h p.i., cells were washed with 1x PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and the plaques were visualized by crystal violet staining.

Viral RNA was isolated from homogenized organs using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels were then determined by quantitative reverse transcription real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Kit RUO (Altona Diagnostics). An internal control provided by the kit was used as a sample preparation control as well as an extended dry spin step for 10 min at 17,000 g at room temperature.

Measurement of hormone and cytokine/chemokine levels

Testosterone levels were measured in plasma samples using a custom-made MILLIPLEX MAP Multi-Species Hormone Magnetic Bead Panel (Merck), according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a Bio-Plex 200 System with high-throughput fluidics (HTF; Bio-Rad). Estradiol levels in plasma samples were analyzed by ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions. Female hamsters in diestrus were excluded from estradiol analysis. Testosterone and Estradiol levels (Arbor Assays) in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions. All ELISAs were measured on an Infinite M Nano ELISA microplate reader (Tecan).

A panel of 13 cytokines and chemokines (eotaxin, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α and 1β (MIP-1α, -1β), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-12 (IL-12(p70)), interleukin-13 (IL-13), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) was measured in homogenized lungs using a custom-made Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine multiplex (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a Bio-Plex 200 System with high-throughput fluidics (HTF; Bio-Rad). Values measured below detection limit were set to the lower limit of detection specified in the manufacturer’s instruction.

Infection of human cells with respiratory viruses

Calu-3, Huh-7, CaCo-2, A-498 and DAOY cells were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h, cells were infected with SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 or H1N1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 in 500 μL EMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine and 2% FBS or EMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine and 0.4% BSA, respectively, for 45 min at 37°C. After washing twice with 1x PBS, 2 mL of infection medium EMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine and 2% FBS or EMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine, 0.2% BSA and 1 μg/mL TPCK-treated Trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) were added and the cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C.

Aromatase activity in SARS-CoV-2-infected Calu-3 cells

Calu-3 were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h, cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 at an MOI of 0.01 in 500 μL EMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine and 2% charcoal-stripped FBS for 45 min at 37°C. At 24 h p.i., cells were treated with 100 nM testosterone and 1 μM letrozole or as control with DMSO. Testosterone and estradiol levels were measured in cell culture supernatants at 24 h post treatment and 48 h p.i.

Isolation and poly(I:C) treatment of lung macrophages from golden hamsters

Male and female hamsters were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of pentobarbital (800 mg/kg). Lungs were perfused with PBS and digested with 2 mL of collagenase (1 mg mL−1) and deoxyribonuclease (0.5 mg mL−1) for 1 h at 37°C.65 After the digestion, lung cells were filtered through a 40 μm filter, resuspended and seeded in 12-well plate. Isolated macrophages were cultivated in RPMI medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with 10% FBS, 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine. After 7–10 days, macrophage cell purity was determined via FACS analysis using anti-mouse CD68 antibody (BioLegend). Cells were incubated with FC block antibody (2.4G2: BD Bioscience) and then fixed for 1 h at RT with True Nuclear Transcription Buffer Set (BioLegend). Cells were stained with CD68 antibody (BioLegend) in Perm Buffer (BioLegend) for 45 min at 4°C. Cells were acquired with Cytek Aurora (Biosciences). The expression of CD68 was assessed with FlowJo software (Treestar). Poly(I:C) treatment was started with >85% CD68 positive macrophage cultures. Macrophages were treated with 5 μg mL−1 and 10 μg mL−1 poly(I:C) or as a control treated with PBS for 24 h at 37°C.

RNA isolation

RNAprotect-fixed tissues were homogenized in 1 mL TRIZOL (Invitrogen) with 5 sterile, stainless steel beads (Ø 2 mm, Retch) at 30 Hz for 10 min in the mixer mill MM400 (Retsch). Cells were lysed in 500 μL or 1 mL TRIZOL (Invitrogen) per well, according to the well size, incubated for 5 min at RT. The cell lysate was resuspended and transferred into a fresh tube. 125 μL or 250 μL chloroform were added respectively to each sample, vortexed for 30 s and subsequently centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 g.

Total RNA was isolated from homogenized tissues and the aqueous phase of the lysed cells using the innuPREP RNA Mini Kit 2.0 (Analytik Jena) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with an additional on column DNase I treatment using the RNase-free DNase Set (QIAGEN).

Total RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human lung tissue sections was purified using the RNeasy@ FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was eluted in RNase-free water and mixed with 1 U μl−1 RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Determination of mRNA expression levels by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The cDNA synthesis was performed using random nonamer primers (Gene Link, pd(N)9, final concentration: 5 μM), SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions and 2 μg total RNA. The cDNA was generated using the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems; cycle: 25°C for 5 min, 50°C for 60 min, 70°C for 15 min, 4°C hold). Reactions were set up with PCR grade Water (Roche) in LightCycler 480 Multiwell Plate 96 Reaction Plates (Roche). Briefly, 2 μL of cDNA template were added to 10 μL FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche) and 300 nM of forward and reverse primer, respectively. RT-qPCR runs were conducted using LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche) with endpoint fluorescence detection: 10 min at 95°C and 45 amplification cycles (15 s at 95°C, 10 s at 65°C and 20 s at 72°C). Analysis was performed in duplicates for each gene. Negative controls and samples without reverse transcriptase were included to detect contaminations.

Relative expression values were determined using a modified E–ΔΔCt method. Rn-values were exported from the LightCycler 96 Software (Roche) to Microsoft Office Excel 2016 and N0-value for the starting concentration of the transcript in the original sample were obtained with LinReg PCR Software v2018.0.58 The averaged N0-value of the gene of interest (GOI) was then normalized with the average N0-value for HPRT (N0(HPRT)) or RPL32 (N0(RPL32)) of the respective sample. The relative N0(GOI)/N0(HPRT)- or N0(GOI)/N0(RPL32)-expression values of the biological replicates are presented.

In hamsters, HPRT (Hypoxanthin phosphoribosyltransferase 1) was used as a reference gene for analyses of mRNA expression levels in the lung as well as in the brain. YWHAZ (Tyrosine 3-Monooxygenase/Tryptophan 5-Monooxygenase Activation Protein Zeta) was used as a reference gene for analyses of mRNA expression levels in the gonads. In human samples, RPL32 (ribosomal protein L32) was used as a reference gene for analyses of mRNA expression levels in the lung as well as in the colon. β-actin (ACTB) was used as a reference for analyses of mRNA expression levels gene in the liver as well as in the kidney and cytochrome c1 (CYC1) was used as reference for the brain. The primer sequences used for RT-qPCR are listed in Table S4, available at Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/8yr83bz9b3.1.

Letrozole detection by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Concentration of letrozole in plasma and lung tissue was measured using an isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany) and was based on the method published before.66

For extraction of letrozole, serum and supernatant of lung tissue lysate were mixed with 0.1% o-Phosphoric acid and icecold acetonitrile was added. Following centrifugation (serum: 10 min, 15,000 rpm 10°C; lung: 20 min, 15,000 rpm, 4°C; Multifuge 1 S-R, Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm centrifugal filter unit (15 min, 3,500 rpm at 4°C, VWR International, Radnor, USA). Filtrates were frozen at −30°C until HPLC injection.

Measurements were performed using the following HPLC equipment: an LC-20 AT pump, degasser unit DGU-20A, oven CTO-20A set at 35°C, UV detector SPD-20A set at 240nm, CBM-20A prominence controller (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of 20 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5) and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v). The flow rate was 1 mL/min and the injections were carried out through a 20 μL loop. Separations were obtained on a pre column and a main column (Nucleosil 120-5, C18, 50/4 and Nucleosil 120-5 C18, 250/4, Macherey und Nagel, Düren, Germany). Letrozole 96% (Sigma Aldrich GmbH) was used as an internal control. Linearity of letrozole: 0.01 μg/mL serum – 20.0 μg/mL serum and 0.068 μg/g lung – 77.85 μg/g lung. LLOQ of letrozol: 0.01 μg/mL serum and 0.068 μg/g lung.

Differential gene expression analysis by stranded mRNA-Seq preparation and sequencing of cDNA libraries

Preparation of stranded cDNA libraries was performed with Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation kit, starting with 1000 ng total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing of the prepared stranded cDNA libraries was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 550 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.). In total, 30 cDNA libraries were paired-end sequenced in rapid mode with 2 × 75 cycles in two runs. Data analysis and base calling were accomplished with an in-house software platform as recently described.59

In total, 103 Gb sequence data were obtained for the 30 cDNA libraries, with an average of about 3.3 Gb (lowest 2.8 Gb) per library. The sequencing raw data for all libraries has been made available on the EBI ArrayExpress server (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress), with the accession number E-MTAB-13100.

Transcript mapping and differential gene expression analysis