Abstract

Fifty-eight clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6B, including 16 from Alaska, 14 from Arizona, 11 from Washington, and 17 from seven additional states, were analyzed. The antibiograms of these isolates were assigned to 10 antibiotic profiles based on their susceptibilities to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Thirty-two (55%) of these isolates were penicillin nonsusceptible, while 21 (36%) were intermediate or resistant to three or more antibiotics. The restriction endonucleases ApaI and SmaI were used to digest intact chromosomes, and the fragments were resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns were combined, and 13 of the 16 Alaskan isolates showed indistinguishable PFGE patterns. One other isolate exhibited highly related ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns, differing by only one band after restriction with ApaI. Among the 14 isolates from Arizona, 1 was indistinguishable from the predominant ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns seen in the Alaskan isolates; 5 others were highly related (±1 band after cutting with either enzyme) to the Alaskan isolates, suggesting a common ancestral origin. Of the remaining eight isolates, six additional ApaI plus SmaI PFGE patterns were observed. The 28 isolates from the various contiguous states had 22 ApaI plus SmaI PFGE patterns. No correlations were found between specific PFGE patterns, antibiograms, dates of isolation, or geography. The serotype 6B isolates across the contiguous United States were genetically diverse, while the 6B isolates from Alaska appeared to be much less diverse.

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains a leading cause of bacterial pneumonia, otitis media, sepsis, meningitis, and bacteremia worldwide, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. In the United States it is estimated that S. pneumoniae is responsible for at least one-fourth of all community-acquired pneumonia (6). Over the past decade in the United States, there has been an increase in the number of reports of pneumococcal isolates that are either moderately or completely resistant to penicillin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) (28). Isolates resistant to these antibiotics appear to belong to a few selected serogroups and/or serotypes (6B, 14, 19F, 23F, 9V) (1, 11, 14). These serotypes are commonly associated with invasive disease and are most frequently isolated from children with serious infections (4).

In Alaska, the highest reported rate of invasive pneumococcal disease exists among Alaska Natives, specifically Yup’ik Eskimo infants, from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (YKD) region, where 1 in every 40 infants is diagnosed with the invasive disease during their first 2 years of life, a rate of 1,000 per 100,000 per year. This rate is 8 to 10 times higher than for other U.S. population groups (7, 10). Many more cases of pneumococcal disease go undiagnosed because of inaccessibility to culture before empiric antibiotic administration (10). In Alaska since 1986, there has been a 6.5-fold increase in the occurrence of pneumococcal isolates causing invasive disease that have reduced susceptibility to penicillin (MIC ≥ 0.125 μg/ml), an 8-fold increase in ceftriaxone resistance (MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml), a 12-fold increase in erythromycin resistance (MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml), and a 26-fold increase in TMP-SMZ resistance (MICs, ≥4 and 76 μg/ml) (24). The highest rates of penicillin-nonsusceptible and multidrug-resistant pneumococci have been found among Alaska Natives of the YKD region of the state. These isolates now represent ≥30% of the total S. pneumoniae isolates from the YKD area. In the last few years, these isolates have spread to other areas within Alaska. Of these isolates, a majority (80%) have been identified as serotype 6B (24).

In this study, we utilized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to analyze susceptible and multidrug-resistant invasive pneumococcal serotype 6B isolates from Alaska and Arizona, where high rates of pneumococcal disease in infants are also seen (9), to determine if these isolates are genetically related. For comparison, 6B isolates from Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Ohio, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin were included.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Sixteen Alaskan isolates of serotype 6B were selected from pneumococci submitted to the Arctic Investigations Program, located in Anchorage, Alaska, as part of statewide surveillance. This group of isolates included penicillin-susceptible and intermediate isolates, represented a range of susceptibilities to three other antibiotics (TMP-SMZ, erythromycin, and tetracycline), were from patients from various service units of the state (Anchorage, 2; Interior, 1; YKD, 13), and were spread over a period of 10 years (1982 to 1992). Fourteen pneumococcal isolates were from Native Americans from the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona (Mathuram Santosham, Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Health). Eleven isolates obtained from Washington (Douglas Black, Surveillance Group for Drug Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Washington State) and 18 isolates (Georgia, 4; Maryland, 1; Massachusetts, 1; Oklahoma, 2; Ohio, 3; Texas, 6; Wisconsin, 1) submitted to the Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, were also analyzed. All isolates were serotype 6B, and most were from children less than 3 years old.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing of 6B isolates from Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin was performed by the standard agar dilution method, as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (23). The following antibiotics were tested: penicillin, erythromycin, TMP-SMZ, and tetracycline. The susceptibilities of isolates from Washington were determined by broth microdilution methods, as described by NCCLS (23), with the exception of tetracycline, the susceptibilities for which were determined by the ability of the isolates to grow in the presence of 10 μg of the antibiotic per ml. The MIC was determined to be the lowest concentration of antibiotic that inhibited growth. For the purposes of this study, penicillin-intermediate isolates were defined as having a MIC of ≥0.125 μg/ml, and resistant isolates were defined as having a MIC of ≥2 μg/ml. TMP-SMZ-intermediate and -resistant isolates were defined as having MICs between 1/19 and 2/38 μg/ml and ≥4/76 μg/ml, respectively. Resistance to tetracycline was defined as a MIC of ≥8 μg/ml; erythromycin-intermediate and -resistant isolates were defined as having MICs of 1 to 2 μg/ml and ≥2 μg/ml, respectively, with NCCLS breakpoints (23).

DNA preparation and restriction enzyme digestion.

Bacteria were grown for 18 to 22 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 on Brucella agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 5% sheep blood. Bacterial cells were resuspended in 2 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco) to an optical density at 560 nm adjusted to read between 0.4 and 0.6. The cells were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature and washed with 1.0 ml of buffer A (10 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl [pH 8.0]). The bacterial pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of low-melting-point agarose (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) prepared in 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM disodium EDTA [pH 8.0]) held at 50°C. Three hundred microliters of each bacterial suspension was poured into Plexiglas molds (Bio-Rad). After solidification, bacteria embedded in the agarose blocks were incubated in 5 ml of TE buffer (0.01 M Tris, 0.001 M EDTA [pH 8.1]) supplemented with 1 mg of proteinase K per ml and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 50°C for 72 h. Blocks were washed with TE buffer three times at room temperature for 15 min each and stored in TE at 4°C. Gel plugs were cut from the block and digested with 35 units of enzyme overnight in 150 μl of sterile distilled water with 22 μl of the appropriate 10× restriction buffer. Two enzymes with rare recognition sites were used: ApaI (Promega, Madison, Wis.) recognizes 5′-GGGCCC-3′; SmaI (Promega) recognizes 5′-CCCGGG-3′. Both of these enzymes have previously been used for PFGE analysis of S. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA (5, 11, 12, 13, 16, 20, 27).

PFGE.

The digested DNA plugs were placed in wells of a 1% agarose gel (SeaKem; FMC Corp., Rockland, Maine) prepared in 0.5× TBE (pH 8.0) and sealed with 1% low-melting-point agarose at 50°C. The digested DNA plugs were electrophoresed in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field apparatus (CHEF DRII; Bio-Rad) with initial to final switch times ranging from 1 to 15 s at 175 V for 20 h with SmaI-digested DNA plugs and for 22 h with ApaI-digested DNA plugs. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide solution (1 mg/ml) for 1 h, destained in distilled water for 4 h, and photographed under UV transillumination.

Analysis of PFGE profiles.

Analysis of PFGE profiles was performed by visual inspection of photographs of ethidium bromide-stained gels. The total numbers of visible bands were counted for each isolate, and patterns were compared. Once isolates were recognized as having identical patterns, a representative of the group was used to compare its pattern with those of similar isolates. ApaI digests yielded patterns of 10 to 15 fragments of 48.5 to 242.5 kb. SmaI digests yielded patterns of 8 to 10 fragments of 48.5 to 242.5 kb. Isolates were assigned to a major pattern designation (A1 or S1) when they showed the same PFGE pattern and to the same subtype (A11, S11, etc.) when band differences were consistent with a single genetic event (one to three band differences), as previously described (5, 33). Isolates that differed by more than three bands were considered unrelated (3, 33). This is more restricted than suggested by Tenover et al. (31), whose guidelines were intended for use in analyzing isolates obtained during potential outbreaks spanning short periods of time.

Coefficients of similarity (CS = number of shared bands × 2 × 100/total number of bands in the two samples) were determined for some isolates as a means of quantitating the relatedness or lack thereof among these isolates (11, 12, 18, 20). When PFGE patterns between isolates following digestion with one restriction enzyme were compared, the CS value was given as a single percentage, whereas a range of CS values was given when isolates were analyzed after digestion with two restriction enzymes. Isolates with CS values of more than 80% were considered to be related. In addition, relatedness of two isolates was considered to be greater when the PFGE restriction patterns for both enzymes gave indistinguishable patterns than when only one of the two enzymes gave indistinguishable patterns.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

A total of 58 isolates were analyzed (Table 1). The isolates were assigned to 1 of 10 antibiotic profiles based on their susceptibilities to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and TMP-SMZ. Overall, 32 (55%) of the isolates were intermediate or fully resistant to penicillin. Isolates from both Alaska Native and Native American patients accounted for 21 (66%) of the penicillin-nonsusceptible isolates. Twenty-nine (50%), 22 (38%), and 14 (24%) isolates were intermediate or fully resistant to TMP-SMZ, erythromycin, and tetracycline, respectively. Twenty-one (36%) of the 58 isolates were resistant to three or more of the antibiotics tested. Isolates susceptible to all four antibiotics (profile A) were from geographic regions other than Alaska (Table 1). The majority of isolates (86%) from Arizona were susceptible to three or more of the antibiotics tested (profiles A and B). Isolates fully resistant to penicillin (profile C) were from Texas (four isolates) and Georgia (four isolates). All of the seven isolates that showed intermediate or full resistance to all of the antibiotics tested (profile E) were from Alaska.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic profiles of serotype 6B clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae from selected areas within the United States

| Antibiotic profile | Antibiotic susceptibilitya

|

Geographic regionb (no. of isolates)

|

Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | TMP-SMZ | ERY | TET | AK | AZ | WA | Other | ||

| A | S | S | S | S | 0 | 7 | 2 | TX (2), OH (3), MD (1) | 15 |

| B | I | S | S | S | 2 | 5 | 0 | OK (1) | 8 |

| C | I/R | R | R | S | 1 | 0 | 0 | TX (4), GA (4) | 9 |

| D | S | R | S | S | 1 | 1 | 3 | MA (1), OK (1) | 7 |

| E | I | R | I/R | R | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| F | I | I/R | S | S | 0 | 1 | 2 | WI (1) | 4 |

| G | I | S | I/R | R | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| H | S | S | S | R | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| I | S | R | I | S | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| J | S | R | I | R | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 14 | 10 | 18 | 58 | ||||

PEN, penicillin; ERY, erythromycin; TET, tetracycline; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

AK, Alaska; AZ, Arizona; GA, Georgia; MD, Maryland; MA, Massachusetts; OH, Ohio; OK, Oklahoma; TX, Texas; WA, Washington; WI, Wisconsin.

Analysis of pneumococcal DNA by PFGE.

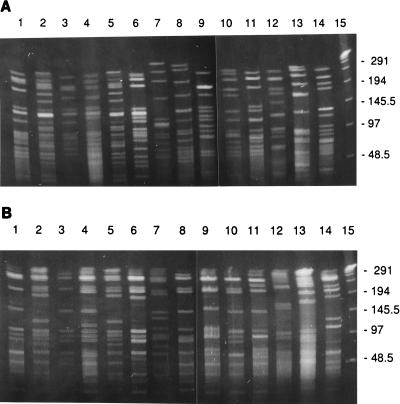

The stability of ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns was determined by selecting one isolate (4463) and looking at the PFGE patterns before and after 50 in vitro passages (data not shown). In addition, reproducibility of the PFGE patterns was established by repeated testing of the same isolate on separate occasions on different gels; all such tests yielded identical PFGE patterns, suggesting stability of the PFGE patterns. All isolates were digested with ApaI and SmaI, and the PFGE banding patterns were visually compared. Figures 1A and B show representative PFGE patterns of DNA digested with ApaI and SmaI, respectively, from isolates taken from the different geographic locations. Thirteen of the 16 Alaskan isolates showed indistinguishable PFGE patterns (A1 S1), while one isolate (4457) was highly related (CS = 97%), showing one extra band after restriction with ApaI (A11) and an identical SmaI pattern (S1) (Table 2). Among the 14 isolates from Arizona, 1 isolate (1130) was indistinguishable from the predominant ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns seen in the Alaskan isolates (A1 S1); 5 others (2398, 2402, 2404, 2396, and 2399) were highly related (A11 plus one band between 145 and 242 kb, A12 minus one band between 48.5 and 97 kb, S12 plus one band between 97 and 145.5 kb, and S13 plus one band between 48.5 and 97 kb) (CS, 90 to 97%). Thus, these 20 isolates from Alaska and Arizona are likely to have had a common ancestor, and we believe they represent a clone.

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of ApaI (A) and SmaI (B) digests of genomic DNA from serotype 6B clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae from various geographic locations in the United States. Lanes 1 to 4, Alaska (917, 4463, 4464, 4465); lanes 5 to 7, Arizona (1129, 1131, 2403); lanes 8, Texas (3371); lanes 9, Georgia (3205); lanes 10, Ohio (1128); lanes 11, Texas (2773); lanes 12 to 14, Washington (158, 133, 137); lanes 15, λ standard. Numbers on the right are molecular size standards of λ concatemers, in kilobases.

TABLE 2.

Properties of serotype 6B clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae from selected areas within the United States

| Strain | Yr of isola- tion | Origina | Antibiotic susceptibilityb

|

PFGE patternc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | TMP-SMZ | ERY | TET | ApaI | SmaI | |||

| 4456 | 1982 | AK (YKD) | I | S | S | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4458 | 1987 | AK (YKD) | I | S | I | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4459 | 1987 | AK (YKD) | I | S | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 917 | 1988 | AK (INT) | S | R | S | S | A1 | S1 |

| 4460 | 1989 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4461 | 1990 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4462 | 1991 | AK (YKD) | I | S | I | R | A1 | S1 |

| 1042 | 1991 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | S | A1 | S1 |

| 4464 | 1992 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4466 | 1992 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4468 | 1992 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4469 | 1992 | AK (YKD) | I | R | R | R | A1 | S1 |

| 4467 | 1992 | AK (ANC) | I | R | I | R | A1 | S1 |

| 1130 | 1993 | AZ | S | R | S | S | A1 | S1 |

| 4457 | 1983 | AK (YKD) | I | S | S | S | A11 | S1 |

| 2398 | 1994 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A11 | S1 |

| 2402 | 1995 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A11 | S1 |

| 2404 | 1995 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A11 | S1 |

| 2396 | 1994 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A11 | S12 |

| 2399 | 1994 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A12 | S13 |

| 4463 | 1991 | AK (ANC) | S | S | S | R | A2 | S2 |

| 4465 | 1992 | AK (YKD) | I | S | S | S | A3 | S11 |

| 1134 | 1995 | AZ | I | S | S | S | A4 | S6 |

| 1133 | 1995 | AZ | I | S | S | S | A41 | S6 |

| 2401 | 1995 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A5 | S5 |

| 1129 | 1990 | AZ | I | S | S | S | A6 | S3 |

| 2400 | 1995 | AZ | I | S | S | S | A6 | S3 |

| 1131 | 1994 | AZ | I | S | S | S | A7 | S4 |

| 1132 | 1994 | AZ | I | I | S | S | A8 | S5 |

| 2403 | 1995 | AZ | S | S | S | S | A9 | S7 |

| 3371 | 1994 | TX | R | R | R | S | A10 | S141 |

| 2772 | 1995 | TX | R | R | R | S | A10 | S14 |

| 2946 | 1995 | WA | I | R | S | S | A101 | S13 |

| 25 | 1995 | WA | I | R | S | S | A102 | S51 |

| 2773 | 1995 | TX | R | R | R | S | A11 | S81 |

| 1456 | 1994 | GA | R | R | R | S | A11 | S81 |

| 467 | 1995 | GA | R | R | R | S | A11 | S8 |

| 3205 | 1994 | GA | R | R | R | S | A111 | S8 |

| 574 | 1996 | GA | R | R | R | S | A12 | S9 |

| 1307 | 1987 | TX | S | S | S | S | A13 | S121 |

| 1088 | 1985 | TX | S | S | S | S | A14 | S1 |

| 2851 | 1994 | WI | I | R | S | S | A15 | S13 |

| 1128 | 1985 | OH | S | S | S | S | A16 | S1 |

| 1283 | 1987 | OH | S | S | S | S | A17 | S15 |

| 1793 | 1987 | OH | S | S | S | S | A18 | S19a |

| 1153 | 1985 | MD | S | S | S | S | A19 | S121 |

| 1247 | 1985 | MA | S | R | S | S | A19 | S12 |

| 171 | 1996 | WA | S | R | I | S | A19 | S1 |

| 174 | 1996 | WA | S | R | S | S | A191 | S1 |

| 2494 | 1993 | TX | R | R | R | S | A191 | S81 |

| 2498 | 1994 | OK | I | S | S | S | A20 | S10 |

| 3115 | 1994 | OK | S | R | S | S | A21 | S11 |

| 20 | 1995 | WA | S | S | S | R | A22 | S16 |

| 64 | 1995 | WA | S | R | S | S | A23 | S171 |

| 133 | 1996 | WA | S | R | S | S | A23 | S19 |

| 102 | 1996 | WA | S | S | S | S | A24 | S17 |

| 137 | 1996 | WA | S | S | S | S | A25 | S18 |

| 158 | 1995 | WA | S | R | R | R | A26 | S20 |

AK, Alaska; ANC, Anchorage; AZ, Arizona; GA, Georgia; INT, Interior; MD, Maryland; MA, Massachusetts; OH, Ohio; OK, Oklahoma; TX, Texas; WA, Washington; WI, Wisconsin.

PEN, penicillin; ERY, erythromycin; TET, tetracycline; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Each ApaI and SmaI PFGE pattern was assigned a letter and number designation (A1 to A26, S1 to S20); isolates having patterns that differed from these patterns by one to three bands were considered closely related and were clustered into subtypes, e.g., A41.

Six additional combined PFGE profiles were seen in the remaining eight isolates from Arizona (Table 2). Of these, isolates 1133 (A4 S6) and 1134 (A41 S6) were indistinguishable from each other except for an extra band in 1133 after cutting with ApaI. In addition, isolates 2400 (A6 S3) and 1131 (A6 S3) were indistinguishable.

Among the 28 isolates from the other eight states, 22 additional combined PFGE patterns were present. Of these, several clusters of isolates with related PFGE patterns were identified. The first cluster included isolates 3371 (A10 S141) and 2772 (A10 S14) from Texas, which were indistinguishable except for one extra band after restriction with SmaI (CS = 95%), and two isolates (2946 [A101 S13] and 25 [A102 S51]) from Washington. These four isolates had highly related ApaI PFGE patterns (A10, A101, A102) but different SmaI PFGE patterns (CS = 83%). The two isolates from Washington appeared to be quite different after restriction with SmaI (CS = 78%) and therefore are less likely to be related to each other or the other two isolates in this cluster. Another cluster of isolates (2773, 1456, 467, and 3205) had highly related ApaI (A11, A111) PFGE patterns. Three of these isolates were from Georgia and were indistinguishable after restriction with SmaI (S8), while isolate 2773 from Texas showed a similar SmaI PFGE pattern (S81). The third cluster included isolates 1153, 1247, 171, 174, and 2494, with highly related ApaI (A19, A191) (CS = 96%) PFGE patterns but different SmaI PFGE patterns (S1, S81, S12, S121) (CS, 80 to 83%).

Correlation between antibiogram and PFGE patterns.

Of the cluster of 20 isolates with related PFGE patterns, 13 (65%) were intermediate to penicillin; the remaining 7 were susceptible. Eleven of these isolates were intermediate or fully resistant to three or more of the antibiotics tested (profiles C, E, and G). The five isolates that shared the PFGE ApaI pattern A11 were susceptible to all of the antibiotics tested, except for one isolate (4457) which was intermediate to penicillin (Table 2). All five isolates were from Arizona patients.

Among the 16 isolates from Alaska, three predominant PFGE patterns (A1 S1, A2 S2, and A3 S11) and nine different antibiograms were seen (Tables 1 and 2). Fourteen (88%) of these isolates were intermediate to penicillin and showed seven different antibiotic susceptibility profiles to the other three antibiotics tested. The remaining two isolates, 917 and 4463, were susceptible to penicillin but resistant to one other antibiotic (profiles D and H).

Among the 14 isolates from Arizona, seven PFGE patterns (A1 S1, A4 S6, A5 S5, A6 S3, A7 S4, A8 S5, and A9 S7) and four different antibiograms (profiles A, B, D, and F) were seen. Seven (50%) of these isolates were fully susceptible to all four antibiotics tested. Five (36%) were intermediate to penicillin and fully susceptible to the other three antibiotics.

The remaining 28 isolates had 22 combined ApaI plus SmaI PFGE patterns and were found in all 10 of the different antibiograms (Tables 1 and 2). Sixteen (57%) of these isolates were susceptible to penicillin; the remaining 12 were either intermediate or resistant to penicillin. Within the first PFGE cluster (3371, 2272, 2946, and 25), all isolates were penicillin nonsusceptible, resistant to TMP-SMZ, and susceptible to tetracycline. Within the second PFGE cluster (2773, 1456, 467, and 3205), all isolates were resistant to penicillin, TMP-SMZ, and erythromycin. Antibiograms within the third PFGE cluster (1153, 1247, 171, 174, and 2494) were variable, ranging from fully susceptible to multidrug resistant (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Phenotyping and genotyping methods are increasingly being used to monitor the source and transmission of disease, as well as the emergence of strains with increased pathogenicity. While serotyping and antibiotic susceptibility testing have been the most common epidemiologic tools for typing pneumococci, they have relatively limited discriminatory power (2). In contrast, genotyping methods such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (8, 15, 22, 27, 32), ribotyping (19, 29), and PFGE (5, 12, 18) have shown greater discriminatory power for isolates within a single serogroup and have provided evidence for clonality and intercontinental spread of particular drug-resistant pneumococci (8, 11, 19, 21, 25, 26). In this study, we utilized PFGE following ApaI and SmaI restriction digestion of chromosomal DNA to determine genetic relatedness between pneumococcal serotype 6B isolates from different geographic locations in the United States.

The combined PFGE profiles observed in the Alaskan isolates indicated that these 16 isolates are ancestrally related (CS, 90 to 97%), suggesting a common origin. These isolates with the combined ApaI and SmaI pattern A1 S1 were recovered over a 10-year period and had variable antibiograms, with the majority (88%) showing intermediate resistance to penicillin. This suggests that combined PFGE patterns can be relatively stable over a number of years, even as antibiograms change. Six of the 14 isolates from Native American patients from Arizona had ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns that were highly related to those of the Alaskan isolates (CS, 90 to 97%), suggesting a common ancestral origin. However, these six isolates, with the exception of one (1130), were fully susceptible to all of the antibiotics tested, suggesting that one penicillin-susceptible Alaskan isolate (917) may represent the ancestral organism for these penicillin-susceptible Arizona isolates.

The PFGE patterns of the remaining isolates were heterogeneous, with no more than five isolates having the same ApaI or SmaI pattern (CS = 95%) and no more than four isolates having the same combined ApaI and SmaI PFGE patterns (CS = 93%) (Table 2). This is comparable with other studies that have shown that isolates of the same serotype are not necessarily more closely related to each other than isolates of different serotypes (5, 8, 11, 16, 26, 27).

To increase the discriminatory power of PFGE, we used two enzymes for typing purposes. In several cases (the smaller clusters of four to five isolates), the use of three enzymes would have provided greater discriminatory power, as previously described for other bacterial species (33). SmaI digestion, which has been used by a number of laboratories (3, 5, 16, 19, 27, 30, 34), was found to be less discriminatory than ApaI digestion for these isolates.

MLEE has been previously used to subtype pneumococcal isolates (12, 19, 21, 27, 32). Versalovic et al. (32), using MLEE, reported that penicillin-resistant serotype 6B isolates from Alaska were genetically related to Spain, Iceland, and Texas 6B clones. These researchers suggested that common resistant isolates from diverse locations share a recent ancestor or that isolates of a particular phylogenetic lineage are predisposed to develop penicillin resistance. In contrast, penicillin-susceptible pneumococcal 6B isolates presented a heterogeneous collection of multilocus enzyme genotypes (21, 32). While MLEE analysis detects mutations in a variety of genes for metabolic enzymes throughout the entire chromosome, the polymorphism obtained with PFGE fingerprints has been found to be greater than that obtained with MLEE analysis (17); thus, PFGE has the potential to further subdivide pneumococcal isolates judged homogenous by MLEE analysis. Therefore, it will be of interest to compare a larger sample of Alaskan pneumococcal 6B isolates, including penicillin-resistant isolates, with the 6B clones in Iceland, Spain, and Texas by PFGE to assess the relatedness of these pneumococcal clones. It is not known whether the serotype 6B isolates used in this study are identical to those used in previous studies.

In conclusion, this study shows that serotype 6B isolates across the United States are genetically diverse and that 6B isolates from Alaska are genetically less diverse by PFGE analysis, suggesting clonal spread. Whether this clone emerged independently or represents an episode of geographic spread remains to be determined. Our data also show that antibiograms may or may not correlate with specific PFGE patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Deliganis, from Northwest Pharmaceutical Research Network, and T. Fritische, from Laboratory Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, for providing isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum P C. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. An overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeit R D. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiologic analysis of microorganisms. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 190–208. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boken D J, Chartrand S A, Moland E S, Goering R V. Colonization with penicillin-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae in urban and rural child-care centers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:667–672. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler J C, Breiman R F, Lipman H B, Hofmann J, Facklam R R. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections among preschool children in the United States, 1978–1994; implications for development of a conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:885–889. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho C, Geslin P, Vazpato M V. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in France and Portugal. Pathol Biol. 1996;44:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining the public health impact of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: report of a working group. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1996;45:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey T J, Daniels M, McDougal L K, Dowson C G, Tenover F C, Spratt B G. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1306–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortese M M, Wolff M, Almeido-Hill J, Reid R, Ketcham J, Santosham M. High incidence rates of invasive pneumococcal disease in the White Mountain Apache population. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2277–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson M, Parkinson A J, Bulkow L R, Fitzgerald M A, Peters H V, Parks D J. The epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Alaska, 1986–1990: ethnic differences and opportunities for prevention. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:368–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferroni A, Nguyen L, Gehanno P, Boucot I, Berche P. Clonal distribution of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae 23F in France. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2707–2712. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2707-2712.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall L M C, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermans P W M, Sluijter M, Hoogenboezem T, Heersma H, Van Belkum A, de Groot R. Comparative study of five different DNA fingerprint techniques for molecular typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1606–1612. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1606-1612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan S. The emerging antibiotic resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 1996;7:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kell C M, Jordens J Z, Daniels M, Coffey T J, Bates J, Paul J, Gilks C, Spratt B G. Molecular epidemiology of penicillin-resistant pneumococci isolated in Nairobi, Kenya. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4382–4391. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4382-4391.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefevre J C, Bertrand M A, Faucon G. Molecular analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae from Toulouse, France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF02113426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefevre J C, Faucon G, Sicard A M, Gasc A M. DNA fingerprinting of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2724-2728.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefevre J C, Gasc A M, Lemozy J, Sicard A M, Faucon G. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis for molecular epidemiology of penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. Pathol Biol. 1994;42:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougal L K, Facklam R, Reeves M, Hunter S, Swenson J M, Hill B C, Tenover F C. Analysis of multiple antimicrobial-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2176–2184. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno C, Crisp J H, Jorgensen J E, Patterson J. The clinical and molecular epidemiology of bacteremias at a university hospital caused by pneumococci not susceptible to penicillin. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:427–432. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. International spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marten A, Parkinson A J, Sorenson U, Tomasz T. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkinson A J, Davidson M, Fitzgerald M A, Bulkow L R, Parks D J. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance patterns of invasive isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Alaska 1986–1990. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:461–464. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichman P, Varon E, Gunther E, Reinert R R, Luttiken R, Marton A, Geslin P, Wagner J, Hakenbeck R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Germany: genetic relationship to clones from other European countries. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:377–385. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-5-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sibold C, Wang J, Henrichsen J, Hakenbeck R. Genetic relationships of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated on different continents. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4119–4126. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4119-4126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares S, Kristinsson K G, Musser J M, Tomasz A. Evidence for the introduction of a multiresistant clone of serotype 6B Streptococcus pneumoniae from Spain to Iceland in the late 1980s. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:158–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spika J S, Facklam R R, Plikaytis B D, Oxtoby M J. Pneumococcal Surveillance Working Group. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1979–1987. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1273–1278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.6.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takala A K, Vuopio-Varkila J, Tarkka E, Leinonen M, Musser J M. Subtyping of common pediatric pneumococcal serotypes from invasive disease and pharyngeal carriage in Finland. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:128–135. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarasi A, Sterk-Zukmanovic N, Sieradzki K, Scheonwald S, Austrain R, Tomasz A. Penicillin-resistant and multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in a pediatric hospital in Zagreb, Croatia. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:169–176. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versalovic J, Kapur V, Mason E O, Jr, Shah U, Koerth T, Lupski J R, Musser J M. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains recovered in Houston: identification and molecular characterization of multiple clones. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:850–856. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia M, Roberts M C, Whittington W L, Holmes K K, Knapp J S, Dillion J R, Wi T. Neisseria gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of strains from North America, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;39:2442–2445. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida R, Hirakata Y, Kaku M, Takemura H, Tanaka H, Tomono K, Koga H, Kohno S, Kamihira S. Trends of genetic relationship of serotype 23F penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Japan. Microbiology. 1997;43:232–238. doi: 10.1159/000239572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]