Abstract

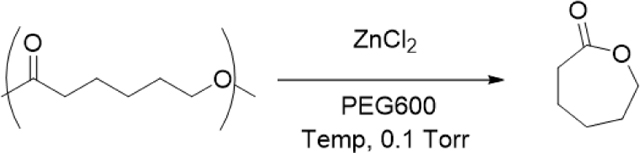

The ability to efficiently and selectively process mixed polymer waste is important to address the growing plastic waste problem. Herein, we report that the combination of ZnCl2 and an additive amount of poly(ethylene glycol) under vacuum can readily and selectively depolymerize polyesters and polycarbonates with high ceiling temperatures (Tc >200 °C) back to their constitute monomers. Mechanistic experiments implicate a random chain scission mechanism and a catalyst structure containing one equivalent of ZnCl2 per ethylene glycol repeat unit in the poly(ethylene glycol). In addition to being general for a wide variety of polyesters and polycarbonates, the catalyst system could selectively depolymerize a polyester in the presence of other commodity plastics, demonstrating how reactive distillation using the ZnCl2/PEG600 catalyst system can be used to separate mixed plastic waste.

Keywords: Depolymerization, Chemical Recycling, Closed-loop

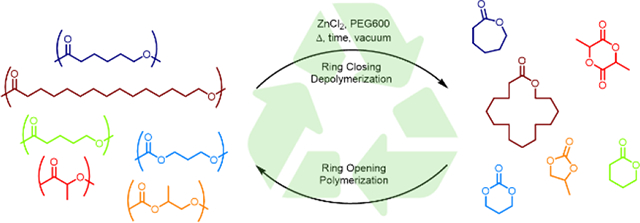

Graphical Abstract

Polyesters and polycarbonates are depolymerized using the combination of zinc dichloride and polyethylene glycol as a catalyst under reactive distillation conditions carried out at temperatures significantly below the ceiling temperature of the polymers evaluated. Selective polyester depolymerization occurred in the presence of other polymer classes, thereby demonstrating the promise for using the chemistry for the chemical recycling of plastics.

Synthetic polymer production exceeds 350 million metric tons annually, which is projected to exceed half a billion metric tons annually by 2050.[1][2] Current commodity polymers have not incorporated end of life into their design, which poses a problem for their ultimate fate. Compounding this problem is that only a small fraction of the recovered waste undergoes recycling.[3] Consequently, most polymeric waste ends up in landfills or is burned for thermal energy. Most plastic waste that is recycled uses a mechanical recycling strategy. This method largely results in downcycled products due to impurities introduced during use and/or from reprocessing. Additionally, the waste stream consists of polymer blends that are difficult to separate and incompatible with one another, which ultimately compromises the recycled polymers’ mechanical properties.[1][2] An attractive alternative for closed-loop recycling is chemical recycling, a process where the polymer is chemically transformed back into its constituent monomer.[1] This method avoids problems with impurities introduced during polymer use and reprocessing, and developing chemoselective depolymerization methods addresses the mixed polymer waste problem.[4]

A number of closed loop ring opening polymerization systems have exploited the propensity of low ceiling temperature (TC) polymers that depolymerize under mild conditions.[1][5–12] The depolymerization of these polymers takes advantage of low ring-strain in the monomer that make depolymerization enthalpically favorable.[13] Consequently, the polymerization of these monomers require low temperatures, extremely active catalysts, conditions that favor polymer precipitation, or monomers that involve multistep syntheses, which limits scalability and their practical use as commodity polymers.

In order to depolymerize polymers with moderate to high TC under relatively mild conditions, the thermodynamic preference for polymerization must be circumvented. One way to achieve this goal is to carry out the depolymerization reactions under reactive distillation conditions, which prevents the polymer/monomer equilibrium from being established by removing the monomer as soon as it is formed.[14] Despite this advantage, reactive distillation of moderate to high TC polymers derived from ring-opening polymerization are uncommonly carried out significantly below the polymer Tc. The high temperatures (>200 °C) often used result in unselective depolymerization reactions.[1][15][16] For example, L-lactide (LLA) production involves the oligomerization of lactic acid followed by Lewis-acid catalyzed, ring-closing depolymerization at high temperatures (>200 °C).[17][18][19] Unwanted side reactions, such as decarboxylation, dehydration, and epimerization are problematic at high conversion and when using higher molecular weight poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA).[19][20][21] Altering the identity of catalysts can lead to more selective depolymerization of PLLA and other moderate Tc polymers,[15][17] but most depolymerization reactions are carried out near the Tc of the polymers. Moreover, there are no general catalysts applied for a wide variety of polymers. Herein, we report a simple and general catalyst for the ring-closing depolymerization of polymers derived from cyclic esters and cyclic carbonates that operates at temperatures significantly below the polymer TC.

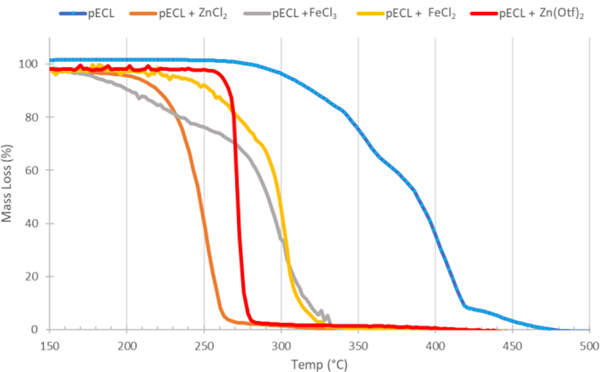

In order to rapidly screen a variety of Lewis acid catalysts, we reasoned that the dynamic flow in a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experiment would mimic the non-equilibrium environment of a reactive distillation reaction, but that could be set up on a small scale and with higher throughput. Therefore, using TGA under nitrogen flow, we screened a number of simple Lewis acid catalysts for the depolymerization of poly(ε-caprolactone) (pECL), which has a TC = 261 °C (Figure 1). Comparing the onset degradation temperature (Td5%), defined as the temperature at 5% mass loss, and the final degradation temperature (Td95%), defined as the temperature at 95% mass loss, we could examine the effect of different simple Lewis acid catalysts on degradation. Thermal degradation without catalyst had the highest Td5% and Td95% (305 °C and 441 °C, respectively) compared to degradation in the presence of Lewis acids. Of the Lewis acids evaluated, ZnCl2 had the second lowest Td5% (203 °C) and the lowest Td95% (262 °C). Consequently, we selected ZnCl2 as the catalyst for further optimization.

Figure 1.

TGA thermograph of pECL in the presence of different Lewis acid catalysts.

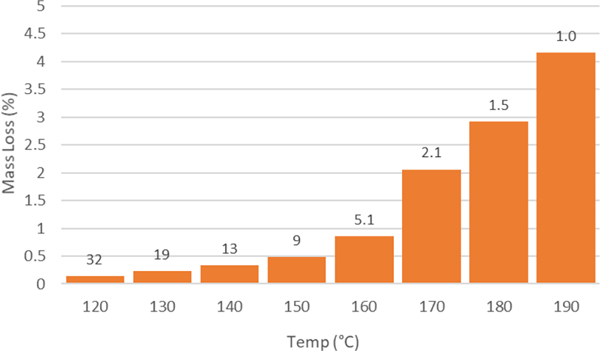

Next, we used a stepped isothermal TGA experiment to identify the optimal temperature for depolymerization. In this experiment, pECL and ZnCl2 was heated from 100 °C to 210 °C, stopping every 10 °C for 30 min. to follow mass loss at each temperature. The data obtained from this experiment is shown in Figure 2 along with the estimated half-life assuming the degradation follows first-order kinetics. We aimed to carry out the depolymerization reactions at the lowest temperature that was practical for depolymerization to conserve energy and to minimize background reactions that may occur at elevated temperatures. Therefore, we selected 160 °C for further screening and optimization because we estimated that the reactive distillation would be >85% complete after 15 h.

Figure 2.

Stepped isothermal TGA heating program for pECL degradation in the presence of 10 wt% ZnCl2. Each bar represents mass loss over 30 minutes. Numbers above bars represent the estimated half-life in hours for pECL degradation, assuming first order kinetics.

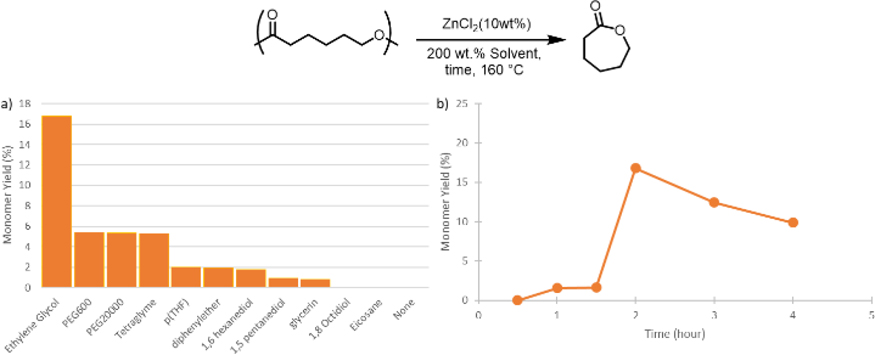

Recently, solvent identity has shown have a large effect on the TC of polymers in solution depolymerization reactions.[19] To assess whether solvent could be beneficial for depolymerization using ZnCl2, we screened a range of readily accessible high boiling solvents, and attempted to depolymerize pECL under dilute reaction conditions at atmospheric pressure (Figure 3a). While none of the solvents resulted in high yields of ε-caprolactone (ECL), polar, coordinating solvents gave significantly higher yields than the non-polar solvent eicosane, which did not produce any monomer. Of the polar solvents studied, monomer yield was highest using ethylene glycol (EG) as the solvent. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR) analysis of a reaction mixture that was heated for 2 h using EG as the solvent revealed a mixture of monomer, polymer, linear oligomers, and cyclic oligomers. Importantly, solvent incorporation into the polymer was not observed by NMR, which suggested that EG was not initiating transesterification reactions. Notably, solvents that contained EG repeat units (e.g., polyethene glycol (PEG) and tetraglyme) produced ECL in higher yields than other polyol solvents that contained more methylene spacers between the oxygen atoms (e.g., poly(tetrahydrofuran) (pTHF) and 1,8-octanediol). These results suggested that the EG had an additional role other than being a solvent for the depolymerization reaction (vide supra).

Figure 3.

a) pECL depolymerization at 160 °C after 2 h in different solvents. b) pECL depolymerization at 160 °C in EG at different reaction times. All reactions included 10 wt% ZnCl2

We next carried out a time course experiment in EG to better understand why the depolymerization reactions in solution did not produce ECL in high yields (Figure 3b). During this experiment, ECL yield was initially low and then peaked at 2 h. At longer reaction times, ECL yield plateaued and then started to decrease. Our hypothesis to explain this behavior is that initial depolymerization to ECL occurs in the first 2 h. At this point, significant buildup of monomer starts to undergo ring opening polymerization to form a mixture of ECL oligomers. Since the temperature of the reaction is below TC for pECL, the reaction reaches an equilibrium that favors short chained oligomers. Repeating the experiment under more dilute conditions would likely lead to more ECL, but dilution is impractical and unworkable at the scale that would be needed to efficiently recycle commercial polymers.[15][21]

Instead, we explored reactive distillation as an alternative to depolymerize pECL below its TC. In order to achieve efficient depolymerization by reactive distillation, the rate of the depolymerization and the rate of removing the monomer must be balanced so that subsequent ring opening of the cyclic monomer is minimized. Fortunately, this requirement was already demonstrated in the initial TGA screening reactions where mass loss was observed at temperatures below the TC of the pECL (Figure 1). In order to best mimic the TGA experiments and to take advantage of the beneficial effects of using a polar additive that we discovered in the solution depolymerization reactions, we hypothesized that a high boiling additive with a low vapor pressure would be needed to carrier out these reactions. Consequently, PEG was chosen as the polar additive because it retains the EG repeat unit that we found to be beneficial for depolymerization while having a tunable boiling point that could be achieved by varying the PEG molecular weight (e.g, PEG600, PEG20000, etc.). Based on experiments carried out with PEG600 in a stepped isothermal TGA (Figure S12), we determined the optimal conditions for reactive distillation (160 °C, 10 wt% ZnCl2, 100 wt% PEG600). Reactive distillation was next carried out by under a 0.1 Torr vacuum (Table 1). Consistent with the TGA experiments and counter to results obtained from depolymerization reactions carried out in solution, the reactive distillation resulted in full depolymerization of pECL with quantitative recovery of ECL after 20 h (entry 1). Control reactions without ZnCl2 (entry 2) or PEG600 (entry 3) resulted in no mass loss, and no ECL recovery. That the depolymerization did not occur efficiently in the absence of PEG600 under these conditions but did occur in the TGA experiment is likely a consequence of more efficient monomer removal in the TGA experiment compared to the reactive distillation. Lowering the temperature to 140 °C resulted in significantly lower yields after 16 h (entry 4), but full recovery of the monomer could be achieved at 140 °C by extending the reaction time to 66 h (entry 5). Lowering the temperature further to 120 °C showed poor ECL recovery even at extended reaction times (entry 6). These results are consistent with the isothermal TGA experiments, which showed no mass loss at temperatures below 140 °C (Figure S13). To evaluate whether PEG600 was required in solvent quantities, less PEG600 was added to the reaction (entries 7 and 8). These reactions revealed that efficient depolymerization could be achieved even when PEG600 was used in additive amounts.

Table 1.

Optimization for the depolymerization of pECL catalyzed by ZnCl2/PEG600. ZnCl2 equiv. based on pECL repeat unit. PEG600 wt% based on polymer mass.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Entry | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | ZnCI2 equiv | PEG600 wt.% | Mass Balance (%) | Remaining Polymer (%) | Isolated Monomer (%) |

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 160 | 20 | 0.08 | 117 | 95 | 0 | 101 |

| 2 | 160 | 16 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| 3 | 160 | 16 | 0.08 | 0 | 99 | 98 | 0 |

| 4 | 140 | 16 | 0.08 | 130 | 98 | 86 | 9 |

| 5 | 140 | 66 | 0.08 | 121 | 96 | 0 | 99 |

| 6 | 120 | 66 | 0.11 | 120 | 101 | 97 | 3 |

| 7 | 160 | 16 | 0.08 | 20 | 98 | <1 | 96 |

| 8 | 160 | 16 | 0.10 | 11 | 91 | 2 | 87 |

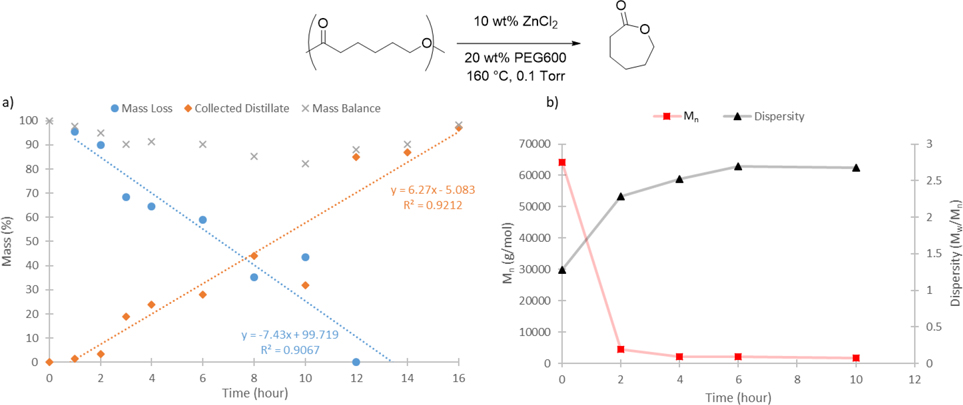

With respect to reaction mechanism, two different depolymerization mechanisms were considered: 1) chain end unzipping, where depolymerization occurs from one chain end to the other, and 2) random chain scission followed by cyclization, where the polymer backbone is broken throughout the polymer resulting in shorter chains that then undergo monomer formation. In order to distinguish these two mechanisms, we conducted reactive distillation using an additive amount of PEG600 at different reaction times and analyzed the remaining polymer residue by gel permeation chromatograph (GPC) (Figure 4). This experiment revealed a roughly linear decrease in pECL mass over time that correlated with a similar increase in ECL yield (Figure 4a). Moreover, polymer analysis revealed a rapid decrease in molecular weight and an increase in dispersity as the reaction proceeded (Figure 4b). These results are more consistent with a random chain scission process rather than chain end unzipping for depolymerization, which would result in a linear decrease in molecular weight occurring without much broadening of the molecular weight distribution as the reaction progressed.[27] A random chain scission mechanism also helps explain the induction period that is observed in the isothermal TGA (Figure S12): no polymer mass loss is expected until after polymer chain scission occurs extensively enough to form the monomer.

Figure 4.

a) Mass of collected distillate ( ), remaining polymer mass (

), remaining polymer mass ( ), and mass mass balance (x) for pECL depolymerization catalyzed by ZnCl2/PEG600 under reactive distillation (0.1 Torr) at different reaction times: b) Polymer molecular weight (Mn,

), and mass mass balance (x) for pECL depolymerization catalyzed by ZnCl2/PEG600 under reactive distillation (0.1 Torr) at different reaction times: b) Polymer molecular weight (Mn,  ) and dispersity (Mw/Mn,

) and dispersity (Mw/Mn,  ) of remaining polymer during the reactive distillation at different reaction times.

) of remaining polymer during the reactive distillation at different reaction times.

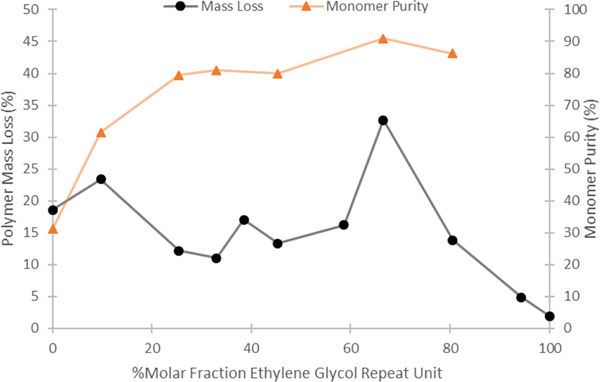

In addition to the mechanism for depolymerization, we were interested in understanding better what role PEG had in the depolymerization reactions. Results from the solvent screen (Figure 3a) and the ability to carry out effective reactive distillations at low PEG loadings (entries 7–8, Table 1) suggested that the PEG additive served a role other than a solvent. One possible role for PEG is that it serves as a ligand for ZnCl2, which is the active form of the catalyst. Unfortunately, efforts to isolate a complex between PEG-600 and ZnCl2 have been unsuccessful. Nevertheless, in order to determine the optimal stoichiometry of EG repeat unit relative to the ZnCl2 that led to the best conditions for depolymerization, reactions were carried out at different mole fractions of PEG-600 and ZnCl2 (Figure 5).[23] Results from these experiments revealed a peak in polymer mass loss that occurred at 2:1 ratio of EG repeat unit in PEG600 to ZnCl2. Additionally, while mass loss is observed when no PEG600 is present with very high ZnCl2 loading, the depolymerization is no longer selective for ECL. This experiment suggests that the highest catalytic activity from this system occurs when two oxygen atoms from PEG are bound to one zinc. Importantly, while the optimal relative EG/ZnCl2 stoichiometry can be determined from this experiment, it does not reveal the number of zinc complexes required for chain scission to occur. Overall, our mechanistic experiments suggest that PEG enables efficient and selective depolymerization of pECL by binding to ZnCl2 to form a particularly effective catalyst that proceeds by a random chain scission mechanism.

Figure 5.

Optimal PEG600/ZnCl2 stoichiometry. Normalized for the number of ethylene glycol repeat units in PEG 600. Reaction conditions: 0.400 g of pECL, 160 °C, 0.1 torr, 4 h. Polymer mass loss ( , left y-axis) monomer purity (

, left y-axis) monomer purity ( , right y-axis)

, right y-axis)

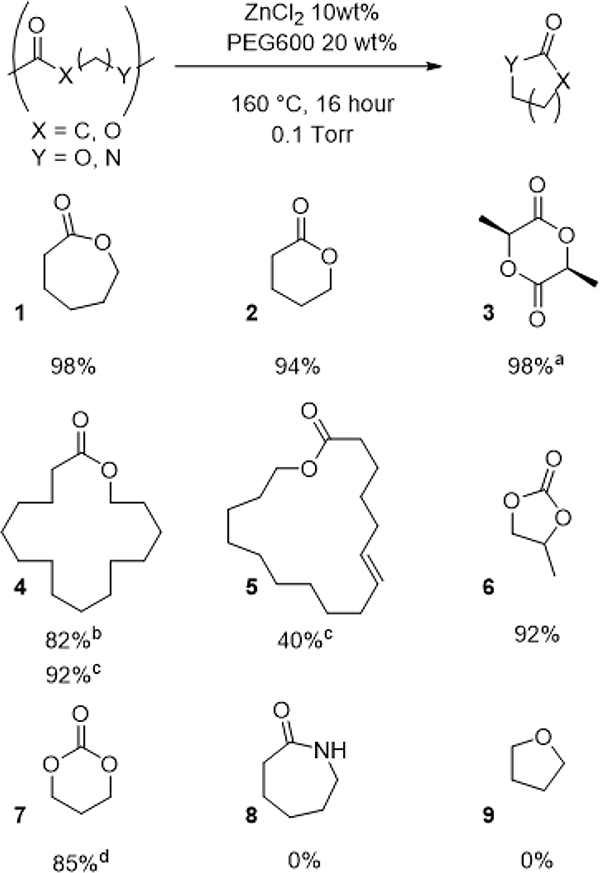

We next explored the generality of the system by carrying out the depolymerization of other polymers (Table 2). Poly(δ-valerolactone) and PLLA could be efficiently depolymerized under the standard reaction conditions to recover 2 and 3, respectively. Notably, PLLA depolymerized with minimal epimerization as 3 was recovered in 99.4% ee and with only 2% of meso-lactide. To test the limit of the depolymerization method, we also explored poly(ω-pentadecalactone) (pPDL) depolymerization. pPDL is interesting because it has properties similar to high density polyethylene.[23][24] Additionally, ω-pentadecalactone (4) is unusual because its polymerization is enthalpically disfavored but entropically favored. Consequently, the most stable molecule derived from 4 polymerizations is its cyclic dimer.[25] Consistent with these thermodynamic properties, depolymerization of pPDL under our standard conditions led to the cyclic dimer of 4 as the primary product. Guided once again by stepped isothermal TGA experiments (Figure S13), we raised the reactive distillation temperature to 210 °C, which led to nearly complete degradation of the polymer and high yields of 4. In addition to pPDL, the polymer derived from the unsaturated macrolactone 6-hexadecenelactone (5) could be depolymerized at 210 °C, albeit in lower yields.

Table 2.

Depolymerization by reactive distillation of various polymers. Isolated yields after reactive distllation

|

2% meso content, 99.4% ee

cyclic dimer obtained as major product;

Rxn. at 210 °C, cyclic monomer obtained as sole product.

The ZnCl2/PEG-600 catalyst system was also suitable for the depolymerization of polycarbonates derived from cyclic monomers. Poly(propylene carbonate) and poly(trimethylcarbonate) could be depolymerized to give excellent yield of 6 and 7, respectively. However, the catalyst system was not suitable for the depolymerization of some classes of monomers. Polyamide nylon-6 did not depolymerize to form 8 under these conditions, and surprisingly, pTHF did not depolymerize to THF 9 despite Lewis acids being known catalysts for pTHF depolymerization.[26]

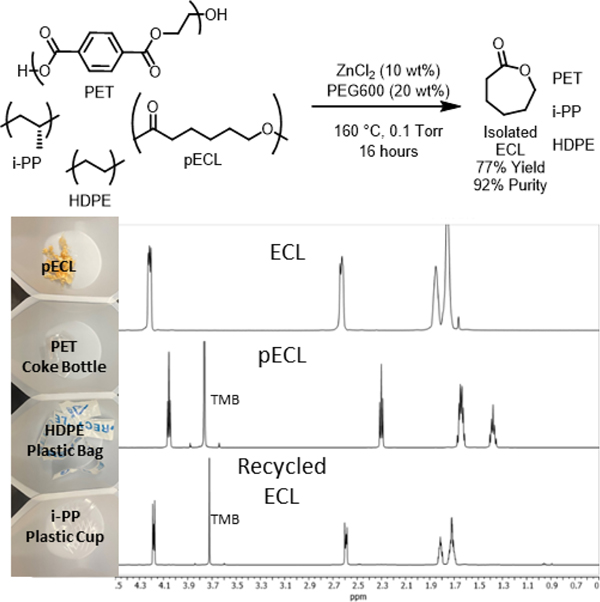

Finally, we wanted to evaluate the sensitivity of the depolymerization catalyst to common impurities that may be present in polymer waste. Therefore, we carried out the depolymerization by combining pECL with equal amounts of post-consumer poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), isotactic poly(propylene) (i-PP), and linear low density poly(ethylene) (LLDPE) (Figure 6 and Figure S14). Under the standard reactive distillation conditions, selective depolymerization of the pECL occurred leading to isolation of ECL in 77% yield (97% mass balance). The ECL in the distillate was very pure (92%), only slightly lower than what was obtained when pure pECL was used in the depolymerization reaction (>98%).

Figure 6.

Reactive distillation of ECLfrom a mixture of post consumer pECL, PET, LLDPE, and i-PP. 1H NMR spectra of initial ECL monomer (top), pECL (middle), and recycled ECL (bottom).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a simple catalyst system that is efficient and selective to depolymerize high TC polyesters and polycarbonates (153 °C < TC < 261 °C) under reactive distillation conditions, including stereoretentive PLLA depolymerization and depolymerization of macrolactones. Mechanistic studies revealed that the depolymerization process occurs by a random chain scission mechanism involving an active catalyst species that contains one ZnCl2 to one EG unit in PEG600. Additionally, pECL depolymerization in the presence of other commodity plastics was possible. These findings demonstrate how carrying out depolymerization reactions with the appropriate catalyst under the non-equilibrium conditions of reactive distillation enables depolymerization reactions that occur significantly below the TC of the polymer. We anticipate that future catalyst development will result in even lower depolymerization temperatures and will provide access to other classes of polymers, which will greatly aid with the broad application of chemical recycling as a viable strategy for plastics recycling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the US Army Research Office grant #66672-CH (W911NF-15-1-0454), the National Science Foundation grant #CHE-1955926, the NSF MRI award CHE2117246, and the NIH HEI-S10 award 1S10OD026910-01A1.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- [1].a) Coates G, Getzler Y, Nature Reviews Materials, 2020, 5, 501 [Google Scholar]; b) Law K & Narayan R, Nature Reviews Materials, 2022, 7, 104 [Google Scholar]; c) Hong M and Chen E, Green Chem, 2017,19, 3692 [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ragaert K, Delva L, Van Geem K, Waste Management, 2017, 69, 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Heller M, Mazor M, Keoleian G, Environ. Res. Lett, 2020, 15, 094034 [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shi C, Reilly L, Kumar V, Coile M, Nicholson S, Broadbelt L, Beckham G, Chen E, Chem, 2021, 7, 2896 [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dainton FS, Ivin KJ, Nature, 1948, 162, 705 [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hong M, Chen E Nature Chemistry, 2016, 8, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hong M, Chen E Ang. Chem. Int. Ed, 2016, 55(13), 4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schneiderman D, Vanderlaan M, Mannion A, Panthani T, Batiste D, Wang J, Bates F, Macosko C, and Hillmyer M ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 4, 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li C, Wang L, Yan Q, Liu F, Shen Y, Li Z Agew. Chem. 2022, 61, e202201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhu J, Watson EM, Tang J, and Chen E Science, 2018, 360(6387), 398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhu J, Chen E Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 1190 [Google Scholar]

- [12].MacDonald JP, Shaver MP Polymer Chemistry, 2016, 7, 3, 553 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shi C, Li Z-C, Caporaso L, Cavallo L, Falivene L, Chen E, Chem 2021, 7, 670 [Google Scholar]

- [14].Segovia-Hernández J, Hernández S, and Petriciolet Chem A. Eng. and Process. 2015, 97, 134 [Google Scholar]

- [15].Olsén P, Undin J, Odelius K, Keul H, and Albertsson A Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Megna IS, Koroscil A Polymer Letters, 1968, 6, 653 [Google Scholar]

- [17].Alberti C, Enthaler S Chemistry Select 2020, 5, 14763 [Google Scholar]

- [18].“Continuous process for the manufacture of lactide and lactide polymers” Gruber PR, Hall ES, Kolstad JJ, Iwen ML, Benson RD, Borchardt RL, U.S. Patent 6,277,951, 2001

- [19].Byers J, Biernesser A, Delle Chiaie K, Kaur A, Kehl J, Catalytic Systems for the Production of Poly(lactic acid), in Synthesis, Structure and Properties of Poly(lactic acid), Di Lorenzo M, Androsch R, Springer, 2018, 67–118 [Google Scholar]

- [20].D Garlotta J. Polym. Environ. 2001, 9, 63 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cederholm L, Wohlert J, Olsén P, Hakkarainen M, and Odelius K Angew. Chem. 2022, 61, e202204531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Olsen P, Odelius K, A. Biomacromolecules, 2016, 17, 699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Job Paul Annales de Chimie. 1928. 10 (9), 113 [Google Scholar]

- [24].Myers D, Witt T, Cyriac A, Bown M, Mecking S and Williams CK Polym. Chem, 2017, 8, 5780 [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cai J, Liu C, Cia M, Zhu J, Zuo F, Hsiao B, Gross R Polymer, 2010, 51(2), 1088 [Google Scholar]

- [26].Martínez-Cutillas A, León S, Oh S and Martínez de Ilarduya A Polym. Chem, 2022, 13, 1586 [Google Scholar]

- [27].Enthaler S and Trautner A ChemSusChem, 2013, 6, 1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yashin V, Isayev A Journal of Polymer Science: Part B: Polymer Physics, 2003, 41, 965 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.